Overview of the Exhibit

Documenting Police Violence and Civil Rights Resistance in a Northern City

The primary goal of the Detroit Under Fire exhibit is to document policies, patterns, and individual cases of police violence and misconduct--including brutality incidents, homicides, and murders--in the city of Detroit during the era of the modern civil rights movement. Equally important, the exhibit documents the persistent and organized resistance to the brutal and racist polices of the Detroit Police Department (DPD) by civil rights and black power groups, by their allies on the white left, and by the many ordinary people who demanded justice when police officers violated the civil and constitutional rights of themselves, their families, and their communities. The overall research findings of this investigation are listed on the next page and then elaborated in detail in five chronological sections that are best navigated through the top drop-down menu. The sections combine narrative and analysis with full reproductions of around 1,500 archival sources used to reconstruct this history, allowing readers to evaluate our project's interpretations through direct assessment of the archival documents and to conduct further explorations and investigations of your own.

The five chronological sections of the exhibit provide the most comprehensive historical documentation of police brutality, misconduct, and fatal force incidents that currently exists for any urban police department in the United States during this time period, building on and utilizing the documentation by civil rights and radical groups at the time--and yet this record that our project has excavated from the very incomplete archive is still only the tip of the iceberg. A key contribution of the exhibit is the identification of 188 law enforcement homicides between 1957 and 1973, including about 75% of the aggregate total officially acknowledged by the Detroit Police Department (which is an undercount)--the most thorough documentation of fatal force encounters that now exists for any city during the civil rights era. For a synthesis and maps of these findings, see the Overview section page on Police Homicides 1957-1973. Each chronological section contains dedicated pages and maps documenting all police homicides, and all brutality and misconduct incidents, uncovered by the research team for that time period (adding up to more than 400 additional bruality, misconduct, and non-fatal shooting incidents in addition to the 188 police homicides). Each section further contains a dozen or more additional pages providing detailed case studies of some of these incidents and analyzing major events, policy developments, and political conflicts interspersed with digitized versions of the archival documents.

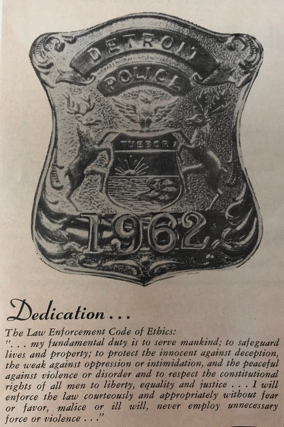

Policing as Racial Control. Detroit Under Fire demonstrates conclusively that there was no sharp divide between the systemic police violence and racial criminalization of Black communities in the urban North and the more familiar story of white supremacy and segregationist law enforcement violence in the Jim Crow South. The Detroit Police Department was an openly racist and almost all-white institution during the 1950s and 1960s, far more dedicated to upholding the color line and abusing African American citizens when they ventured downtown or beyond defined Black neighborhoods than to protecting them from crime and to respecting "the constitutional rights of all men," as the Law Enforcement Code of Ethics promised. The Detroit Police Department did not primarily 'fight crime' in Black neighborhoods; instead the DPD criminalized African Americans collectively in a process of segregationist racial control. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the DPD finally began to hire a significant number of Black officers, racialized police violence and racially targeted law enforcement actually intensified with the implementation of a formal stop-and-frisk law to legalize racial profiling, overt and violent repression campaigns against civil rights and black power organizations, the illegal mass surveillance of activist groups, and a deliberate deployment strategy to deter low-level property crimes against white-owned businesses and residences through fatal force against young Black males that made the DPD the nation's deadliest police department per capita during the early 1970s. At least one-fourth of identified police homicides during the late 1960s and early 1970s, in our project's assessment, were arguably or almost certainly unprosecuted murder or manslaughter cases even under the DPD's deliberately permissive use of force policies.

The Detroit Police Department operated both as an autonomous political institution and as an extension of the punitive and racially targeted policies of both conservative and liberal mayoral administrations, as well as an instrument of the "racial segregationist aims of the dominant white community," as NAACP leader Arthur Johnson testified to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1960. During the civil rights era, Detroit was a deeply segregated and racially divided city where a significant majority of white residents voted for their right to discriminate by race in the housing market in 1964, adamantly opposed the decades-long civil rights demand for a civilian review board to oversee and investigate the police department, enthusiastically supported the 1968 "stop-and-frisk" law to ensure racial profiling and mass criminalization of African Americans, and strongly endorsed the undercover STRESS unit that terrorized Black neighborhoods and killed 22 mostly unarmed people in the early 1970s, among many other punitive and racially targeted law enforcement policies.

This traumatic history of police violence and racism in Detroit is also a story of the resilience, courage, and most of all the sustained political mobilization of civil rights and black power organizations and of everyday Black people in their local communities. In recent years, historians have begun to document the centrality of anti-police brutality activism to urban Black politics in all regions of the country throughout the 20th century, and in particular during the modern civil rights era from the 1950s through the 1970s. In Detroit, as in other cities, the story of African American resistance to police racism and violence started long before the chronological era covered in this exhibit. Detroit Under Fire picks up this history in the late 1950s because that is when the Detroit chapters of the NAACP and American Civil Liberties Union launched an organized campaign to enact a civilian review board to investigate police brutality and misconduct, end the DPD's illegal racial profiling policy of mass "investigative arrests" of Black citizens, integrate the police department to match the racial demographics of the city's population, and protest violent and unconstitutional policing through political and legal methods. These efforts, and subsequent campaigns by other organizations, also created substantial if incomplete records documenting police brutality and misconduct in the archives, without which this project of historical recovery and excavation would not have been possible.

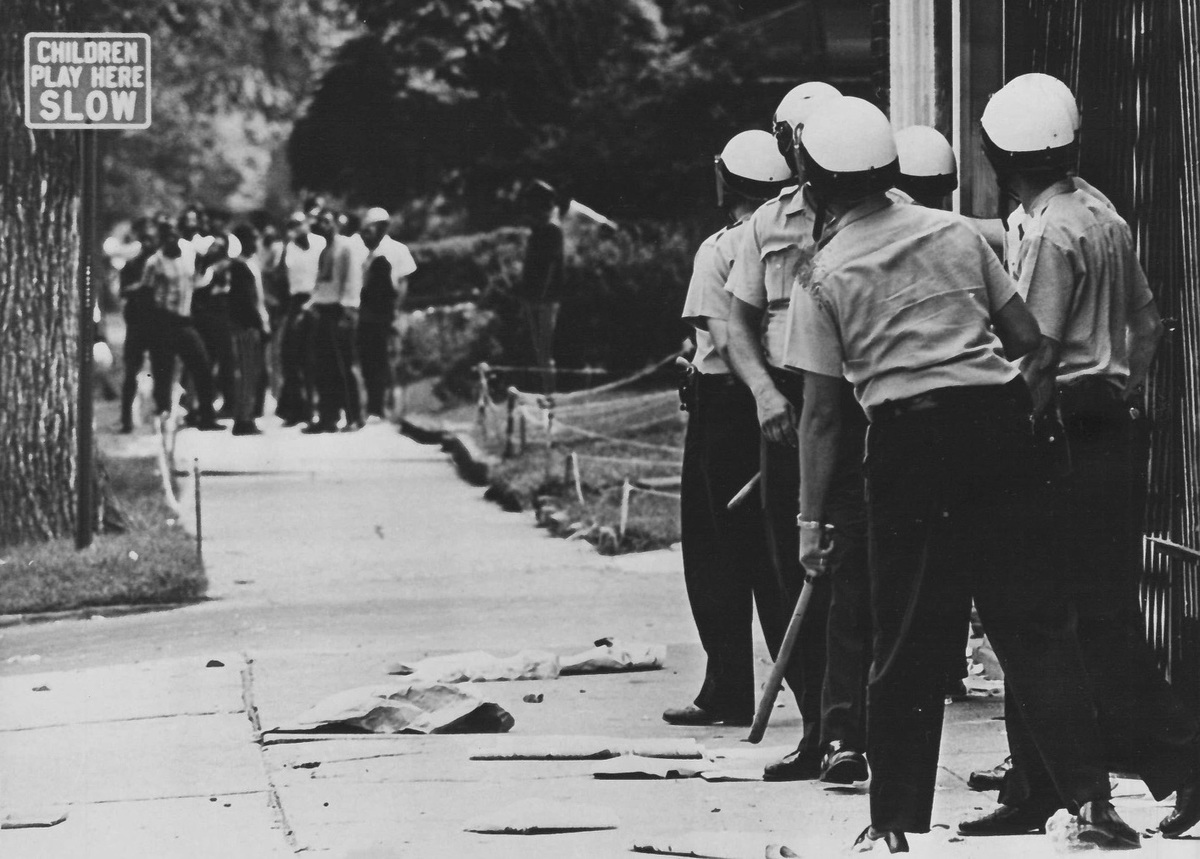

Between 1963 and 1966, black power and other leftist organizations moved to the center of the campaign against police brutality, a grassroots mobilization that created a much more confrontational dynamic in city politics. Black radical activism and other civil rights protests--not just, or even primarily, 'rising crime rates'--led a white liberal mayoral administration to militarize and greatly expand police enforcement in poor Black neighborhoods and along the shifting color line, a local version of what was happening nationally with the federal government's "war on crime." Police brutality was the most immediate cause of the Detroit Uprising of 1967, during which the DPD and other law enforcement agencies shot and killed a minimum of 35 mostly unarmed people, and this escalating cycle of state violence then led to a full-blown conflict between the police department and Black activist groups by the late 1960s. The DPD and the city government consistently denied that police brutality even existed and, with the complicity of the county prosecutor, whitewashed or obstructed all internal and external investigations into misconduct, criminality, and fatal force by police officers. During an era of extreme racial polarization, the DPD's racial violence and open crackdowns on Black political organizations inspired mass protests, especially against the STRESS "murder squad" of the early 1970s, leading to demands for community control of the police department and ultimately the 1973 election of an African American mayor who promised to end the DPD's reign of terror. (The successes and failures of this promise will be the subject of the next phase of this research project, Crackdown: Policing Detroit through the War on Crime, Drugs, and Youth, covering the 1974-1993 era).

Explaining the Exhibit Title. The undergraduate student researchers together chose the title "Detroit Under Fire" to capture the ways in which the Black community in Detroit came under fire not only by police bullets but more broadly by public policies and political discourses of racial criminalization, by racist stereotyping that African Americans were all residents of a dangerous crime-ridden 'ghetto,' and by systemic racial profiling both collectively and as individuals through the actions of law enforcement, white elected officials, the mainstream media, the majority-white public, and other political and cultural institutions. Detroit is probably best known for coming "under fire" during the 1967 Uprising, when certain parts of the city literally went up in flames, for which the political authorities and mass media blamed 'arsonists' and 'criminal rioters' and were clearly far more concerned with the damage to white-owned property than with the loss of African American lives. From our perspective, "Detroit Under Fire" operates both literally and metaphorically to signify that much of the Black community perceived the Detroit Police Department as a violent occupying force not only during the events of July 1967 but throughout the 1957-1973 time period under investigation--a police department that shot and killed more than 200 mostly unarmed people and exonerated itself for almost every act of brutality, misconduct, murder, and other forms of racialized violence committed by its officers.

Detailed Outline of the Exhibit

Detroit Under Fire is organized into five chronological sections that trace the escalation of police violence, the evolution of law enforcement policies and programs, and the mobilization of organized resistance to the DPD during the 1957-1973 time period. Each section provides an overview of these policy developments and key events and also includes specific pages documenting and mapping the police homicides and brutality/misconduct incidents discovered by the research team for that time period. Each research team consisted of three or four undergraduate students who searched for this history in Detroit-based archives and newspaper databases and also created a supplemental map series on the separate ArcGIS StoryMaps platform, working with graduate student consultant Nicole Navarro, that synthesizes all of the maps and key research findings from each section in a more streamlined and user-friendly format. Professor Matt Lassiter, the exhibit editor and lead author, then added content to and updated each section and the supplemental StoryMaps and--while this project is a deeply collaborative enterprise--is ultimately responsible for all interpretations and data contained in Detroit Under Fire.

- Section I: Civil Rights and Police Brutality, 1957-1963. The opening section of the exhibit chronicles the evolution of the NAACP's campaign against police brutality and the demands of civil rights activists for a civilian review board to conduct impartial external investigations of a police department that denied and covered up all wrongdoing. Section I also explores the brutal "crash" crackdown of 1960-1961, when the DPD arrested 1,500 African American males as suspects in a murder investigation, the subsequent mobilization of Black voters to elect a liberal white mayor who promised "color-blind policing," and the failure of ineffective liberal reforms to curb the problem of criminal police violence and racially discriminatory police department policies. The section culminates in the police murder of a 24 year-old Black woman named Cynthia Scott and the mass protests by radical Black organizations against the DPD and prosecutorial coverup of what happened, marking a new grassroots phase in the struggle against police brutality in Detroit. Section I additionally documents 27 police homicides of civilians and 64 other incidents of brutality and misconduct between 1957 and 1963.

- Section II: Liberal War on Crime, 1964-1966. The second section traces the consequences of the "war" on urban street crime in poor Black neighborhoods and in the city's commercial districts declared by white liberal administrations in the city of Detroit and at the federal level in the mid-1960s. Under Mayor Jerome Cavanagh, the Detroit Police Department adopted punitive "get tough" policies that escalated militarized policing and racial profiling, especially in response to urban unrest and black power radicalism, and created new discretionary mechanisms that gave police officers the legal authority to arrest and detain people on any pretext. Facing civil rights pressure, the DPD did establish an internal Citizen Complaint Bureau to investigate misconduct and brutality allegations, but the agency lacked power and almost always exonerated accused officers. Civil rights organizations protested the police murders of unarmed Black people, especially teenagers, and leadership of the anti-police brutality movement shifted to militant new left and black power groups. The DPD cracked down ruthlessly and illegally on these organizations, leading to the Kercheval Incident of 1966, portrayed as the successful quelling of a riot but which was actually a police-instigated confrontation designed to destroy the black power movement in Detroit. Section II additionally documents 17 police homicides of civilians and 163 other incidents of brutality, misconduct, and non-fatal DPD shootings in Detroit between 1964 and 1966.

- Section III, Uprising and Occupation, 1967. The third section provides an in-depth examination of the most well-known event in Detroit's modern history, the seven-day Uprising of 1967 that government authorities labeled a criminal "riot" and a black power "conspiracy," but that many Black Detroiters considered a political rebellion triggered by police brutality. The Uprising began with a routine event, a police raid on an unlicensed bar that resulted in the mass arrest of 85 African Americans, and spiraled out of control as street protests and civil unrest brought the military occupation of the city by the Michigan National Guard and U.S. Army. At least 47 people lost their lives, including 35 documented homicides by the DPD and the occupying military units, along with indiscriminate arrests of around 7,200 people. The vast majority of those killed by law enforcement were unarmed Black males allegedly committing nonviolent low-level property crimes ("looting"). Although the Wayne County Prosecutor declared almost all deaths caused by state agencies to be "justifiable homicides," the evidence is overwhelming that many of them were not. The Detroit Uprising led to a surge of black power activism in Detroit as well as multiple government investigations that sought to uncover the "root causes" of poverty and racial segregation but ultimately justified an expanded police presence in poor Black neighborhoods. In addition to documenting and mapping 47 fatalities during the Detroit Uprising (four more than the widely accepted 'official' total), Section III includes dozens of news media and government-circulated photographs from the events of July 1967 demonstrating how this visual culture operated to erase the violence and responsibility of law enforcement agencies by blaming Black residents of Detroit for causing their own predicament.

- Section IV: Radicalization: Police Violence and Black Power, 1968-1970. The fourth section chronicles the dramatic escalation of police violence, and the parallel mobilization of black power and other radical left organizations, in the polarized aftermath of the 1967 Uprising. The Detroit Police Department engaged in an extraordinary range of politically motivated violence and repression during the late 1960s, including crackdowns on black power activists in high schools, "stop-and-frisk" brutality against Black teenagers in racially transitional neighborhoods, a drunken off-duty assault on Black youth at a church dance, an attack on nonviolent marchers in the Poor People's Campaign, militarized battles against white countercultural youth in public parks, unprovoked assaults on white New Left activists, armed invasion of a Black church hosting a black nationalist conference, organized repression of the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party, and the systematic and illegal surveillance of political groups on a mass scale. The city of Detroit also enacted a formal "stop-and-frisk" law in 1968, the DPD obstructed external investigations of police brutality by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and other outside agencies, and the Detroit Police Officers Association union emerged as an independent reactionary force in local politics. Radical activists mobilized against police repression, and mainstream Black politicians demanded community control over the police department of a racially polarized city approaching a majority African American population. Section IV additionally documents 22 police homicides of civilians, including a deliberate policy change to encourage fatal force against unarmed and fleeing civilians, and 95 other incidents of brutality, misconduct, and non-fatal shootings.

- Section V: STRESS and Radical Response, 1971-1973. The final section of the exhibit revolves around the history of STRESS ("Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets"), an undercover "proactive policing" unit that shot and killed at least 22 people, most of them unarmed Black males allegedly involved in low-level "street crime." STRESS deployed in commercial districts along racial boundaries and was designed to protect white property and gentrify the central city through shoot-first policies that civil rights and black power groups denounced as racial terror tactics by a "murder squad." A broad coalition of civil rights and black power organizations launched a two-year campaign to abolish STRESS and bring about Black community control of the DPD. Massive protests followed the fatal 1971 shooting of two unarmed Black teenagers in a STRESS decoy operation, followed by a DPD and prosecutorial coverup; the Rochester Street Massacre of spring 1972, when a STRESS unit killed and wounded a group of African American sheriff's deputies; and the brutal DPD manhunt of Dec. 1972-Feb. 1973, which involved mass violations of the constitutional rights of Black citizens during the search for three fugitives who engaged in a shootout with an undercover STRESS team. Radical activists also filed a conspiracy lawsuit against the DPD and county prosecutor for covering up the pattern of STRESS murders and protested police corruption following exposure of widespread criminal activity by DPD officers in narcotics trafficking. Section V additionally documents 84 police homicides between 1971 and 1973, including a substantial number that the evidence indicates were unprosecuted murders, and an additional 75 incidents of brutality, misconduct, and non-fatal shootings.

Additional Storytelling and Curricular Products. We recognize that the Detroit Under Fire exhibit, in its quest to document as fully as possible the scope of police violence and activist responses during this period of Detroit's history, is sprawling and dense and perhaps at times overwhelming on this particular platform (the free, open-source Omeka web publishing platform). To facilitate usability and accessibility, the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab has created a series of five supplemental StoryMaps that synthesize the main research findings and include all of the interactive maps in each section of the exhibit. We are also developing a series of multimedia investigative reports that present material from specific pages or sub-sections of the exhibit in the style of long-form digital newspaper articles centering the visual documents rather than the narrative text (these are also hosted separately by the U-M Carceral State Project here). The supplemental StoryMaps and multimedia reports are also designed for classroom use; for more information visit the Curriculum Guides page of the Overview section.

Sources

The interpretations and analysis on this page are drawn from the Detroit Under Fire exhibit. Scholarship about Detroit that informed the approach of this project includes:

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2001)

Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (1996)

Herb Boyd, Black Detroit: A People's History of Self-Determination (2017)

Alexander Elkins, "Battle of the Corner: Urban Policing and Rioting in the United States, 1943-1971" (Ph.D. dissertation, Temple University, 2017)

Austin McCoy, "No Radical Hangover: Black Power, New Left, and Progressive Politics in the Midwest, 1967-1989" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 2016)

Michael Stauch, "Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class, and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit" (Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University, 2015)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)

Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying: A Study in Urban Revolution (2012)

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit (2007)

Stephen Ward, In Live and Struggle: The Revolutiuonary Lives of James and Grace Lee Boggs (2016)

Scott Kurashige, The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis Began in Detroit (2017)

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (2016)