4. Radicalization and Civil Protest

In 1962, newly elected Mayor Jerome Cavanagh had won the support of mainstream civil rights organizations by promising to improve African Americans' lives and reform the Detroit Police Department (DPD). President Lyndon B. Johnson declared national Wars on Poverty and Crime in 1964 and 1965, providing Cavanagh the means to accomplish this goal: the city received millions of dollars to fund antipoverty programs and equip its police force. Middle-class, moderate African American community leaders believed these reforms would lift communities out of poverty and make the city safer. Unfortunately, it soon became clear that, these reforms had failed to transform either poor communities or the DPD. Despite efforts to recruit more African American officers, the police force remained more than 95% white in 1966, and white police officers continued to harass and mistreat African American civilians at disproportionate rates. By coupling the city's efforts to eradicate poverty with its efforts to deter crime, the Cavanagh administration granted the DPD greater discretionary authority in impoverished neighborhoods and then militarized policing with the Tactical Mobile Unit. Many poor, young African American citizens grew frustrated that little had changed and began to believe they needed to take a more radical approach.

Black Power

Mainstream civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had long advocated nonviolent resistance in pursuit of the goals of racial integration and equality for African Americans. As the 1960s progressed, radical factions within the civil rights movement lost faith in the progress its leaders promised and united to push for change under a new ideology—Black Power.

In June 1966, Stokely Carmichael, the recently elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), made the first major call for Black Power. While only twenty-four at the time, Carmichael had worked within the mainstream civil rights movement for years. As a student at Howard University, he participated in voter registration drives and rode interstate buses into the segregated South as part of a campaign to integrate buses called the Freedom Rides. On June 16, 1966, police in Greenwood, Mississippi arrested Carmichael along with other civil rights workers as they set up camp as part of a civil rights march. That evening, he was released and proclaimed to the hundreds gathered outside the jail:

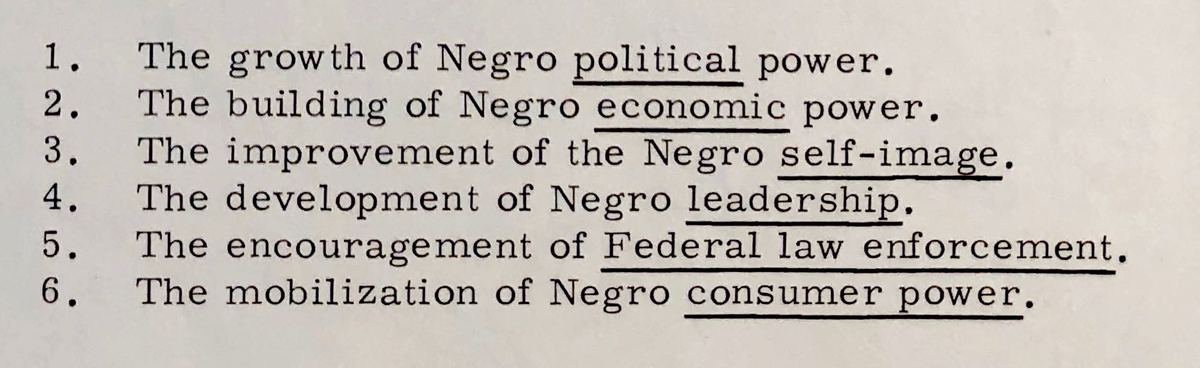

As Carmichael defined it, Black Power was "a call for black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, and to build a sense of community.” The formerly mainstream civil rights organization the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) became another major proponent of Black Power after electing a more militant national director, Floyd McKissick. In a letter to its supporters, CORE warned readers that “the bigot's favorite weapon in this fight to split the friends of freedom is his use of the term black power. As he interprets it, black power becomes black supremacy, black violence, and black hatred for the white man.” Instead, Black Power was a call for black people to transform their own communities. Its goals included:

Stokely Carmichael brought the Black Power movement to national attention, but he was not the first to advocate this ideology. Black Power unified beliefs that had previously been called black separatism or black nationalism. Malcolm X was a prominent black nationalist leader who founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity in 1964 and famously declared the movement's intention to attain "freedom by any means necessary." In Detroit, Reverend Albert Cleage, Jr., was one of the most prominent black nationalist leaders of the early-to-mid 1960s. Cleage led the Central United Church of Christ and also helped establish the Michigan branch of the Freedom Now Party, running as its candidate for governor in 1964. Cleage's organization also frequently protested police brutality, including after the killing of Cynthia Scott in 1963.

In September 1966, Reverend Cleage hosted Stokely Carmichael and other Black Power advocates at a mass rally at his church. The radical underground publication The Fifth Estate covered the rally--you can read the full account in The Fifth Estate article at the top of this page. More than one thousand people filled Cleage's church and responded enthusiastically to Carmichael's speech. As he explained the movement's main goal: “Black people have control of their communities—that's ‘black power' plain and simple and that's what scares the white men in power.” Carmichael urged the mostly African American audience to take pride in their heritage: “We have to love our communities, we have to love black, we have to stop hating ourselves as what we are.”

National and local Detroit leaders of the NAACP and Urban League denounced Black Power because they feared it would divide the civil rights movement, frighten its white allies, and counteract the progress the nation had made. Roy Wilkins, the executive director of the NAACP, criticized those who advocated Black Power in his keynote address to the NAACP National Convention in September 1966:

Francis Kornegay, executive director of the Detroit Urban League, said in 1966 that “working under the slogan ‘black power' as meaning ‘black nationalism' is as divisive as campaigning for ‘white power.'" He compared Black Power to “the theory of ‘separate but equal,' the doctrine the South used for perpetrating segregation until the Supreme Court overturned it in 1964.”

This radical vision divided mainstream and militant civil rights organizations and made the disconnect between middle-class and working-class African Americans more apparent. As militant observed, the civil rights movement’s progress benefitted middle-class African Americans but did not dramatically improve the lives of those in the working class and in the poorest neighborhoods. Floyd McKissick, the head of CORE, explained this disconnect in a speech on December 11, 1966:

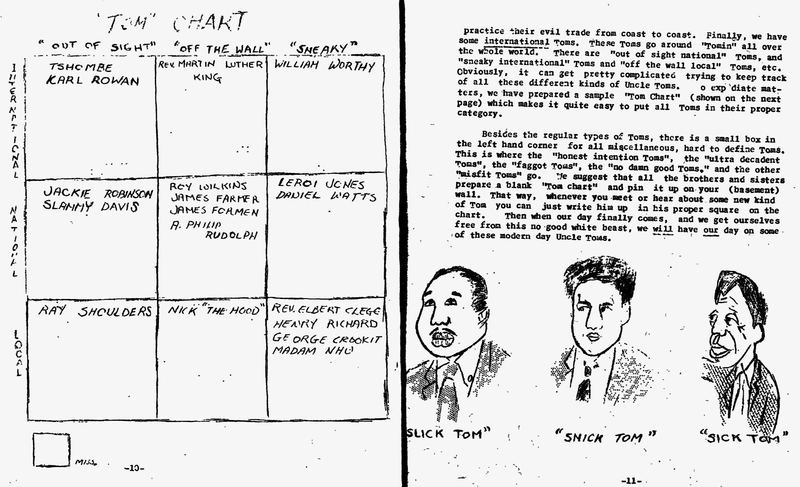

As an example of these class division, some radical African American groups nicknamed middle-class African Americans who worked in the nonviolent civil rights movement “Uncle Toms.” The Black Vanguard, a radical socialist publication produced by the Detroit-based League of Revolutionary Black Workers, described Uncle Toms as those “no good black traitors who have hindered our struggle, worked for the white man, and generally made a nuisance of themselves.” In its August 1965 edition, The Black Vanguard published a chart to help readers categorize the types of Uncle Toms they encountered.

- Out of Sight Toms: “who are so super bold, that it’s hard to ‘see’ how anyone could be so foul.”

- Off the Wall Toms: who “usually come up with some kind of ridiculous, illogical, nonsensical . . . off-the-wall philosophy which is supposed to bring freedom to the black man.”

- Sneaky Toms: who “talk about the Black Revolution” but will “stab you in the back in a minute.”

Take a look at the chart on the right to see how the author categorized more than a dozen civil rights leaders, including Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., NAACP Director Roy Wilkins, Detroit City Councilman Nicholas Hood, and even Reverend Albert Cleage.

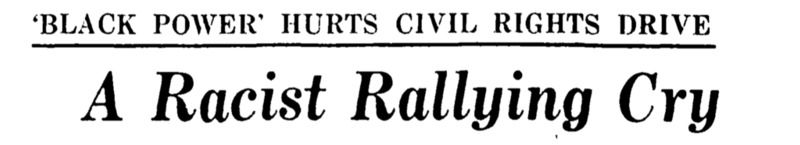

The Detroit News compares Black Power to a kind of "reverse racism" that "is confusing, vague, degrading and damaging to the civil rights effort." July 6, 1966.

As headlines from the mainstream conservative newspaper the Detroit News show, Stokely Carmichael’s initial call for Black Power alarmed many white Detroiters. “Black Power” was both a call to positively value black identity and a call for more radical change, rejecting the philosophy of nonviolence. Black Power advocates argued for the right to self-defense from white racial and police brutality. They did not advocate violence against white America, but many white Americans interpreted the slogan that way. The implications frightened those who benefitted most from the existing political and socioeconomic systems, namely, wealthy white people in positions of power.

Could Detroit Have a Race Riot?

In the wake of destructive urban rebellions in Harlem, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and Chicago, many in Detroit worried that the leaders of militant organizations would lead their followers to start a similar uprising. These disturbances often began in poor, majority African American neighborhoods after police officers confronted young, black men.

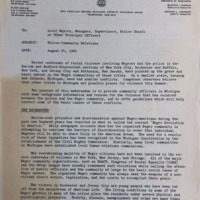

In August 1964, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC) sent this memo to city leaders across the state, offering a set of guidelines to prevent racial disturbances. The report explains that “young people who have been cut off from the mainstream of American life” typically started these disturbances because they had lost “hope or faith in the American dream” and felt “that they [had] nothing to lose.” Furthermore, “frequent contact with the policeman on the beat often makes the policeman the most convenient symbol of total oppression.” While acknowledging that the “total oppression” of African American citizens was the root cause of unrest, the MCRC offered Michigan cities a set of guidelines for taking preventative action by reforming their police departments. The MCRC suggested training police officers in human relations, actively recruiting from minority groups, and establishing procedures for reviewing police brutality complaints. Detroit’s civil rights organizations had offered Cavanagh exactly the same recommendations for years. The city implemented a version of each, with little success.

The Black Power movement’s rise coincided with the radicalization of local civil rights groups in Detroit, in particular the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME). Organized by the SNCC-affiliated Northern Student Movement (NSM) on Detroit’s East Side in 1964, ACME opened a community center at 9211 Kercheval Avenue and helped the neighborhood's residents find housing, jobs, and childcare. ACME’s multiracial members also spoke out against discrimination and harassment faced by African American Detroiters, including against the DPD.

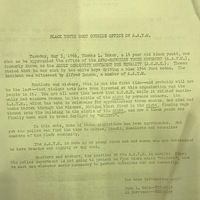

In 1966, in the wake of Carmichael's call for Black Power, white members left the organization and founded Friends of NSM while its black leaders renamed ACME the Afro American Youth Movement (AAYM). The AAYM hosted demonstrations against police brutality throughout the city and accused the police of targeting its members. In May 1966, AAYM member Thomas Baker was shot and injured inside the organization’s headquarters. The police disputed AAYM’s claim that two white boys driving in a car had shot Baker and accused the group of making a false report. In response, AAYM organized rallies protesting police misconduct around the city. The AAYM distributed a flyer about the shooting, writing: “Brothers and sisters, the position of the AAYM is simple: since the police department is not going to protect us from these white ‘racists’ then we must use whatever means necessary to protect ourselves and our community.”

As tensions rose in the summer of 1966, Mayor Cavanagh reassured residents that a riot could not happen in Detroit. In July, he told the press, “The term ‘black power’ is a source of concern for many people, but here there has been a sharing of power. . . . We can thank God in Detroit that we have not had civil disorders. There is a climate of decency here.” Detroit had been named a Model City and received praise for the positive state of race relations. Cavanagh believed that his biracial coalition and the support of civil rights organizations was a major reason for progress.

On August 9, 1966, police officers confronted AAYM activists standing on the street in their own neighborhood. The officers attempted to arrest the men for loitering, but they resisted, shouting "We won't be moved!" For four days, minor scuffles between police and residents broke out, but the unrest failed to spread to other parts of the city. The Kercheval Incident convinced the white city leaders of Detroit that the police department was equipped to protect residents from future uprisings. While community leaders made some efforts to improve living conditions and police-community relations, they achieved limited success.

Following the Kercheval Incident, The Fifth Estate asked Al Harrison, director of the AAYM, “What do you think of Mayor Cavanagh’s concept of shared power?” He responded, “I don’t think very much of Mayor Cavanagh’s concept of ‘shared power,' because there’s no such thing. . . . You either have power or you don’t. Black people don’t. Mayor Cavanagh has power, I don’t. So how can you talk about sharing power when he has all and I don’t have any?”

Sources:

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Fine, Sidney. Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2007.

Gloria Brown Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Hall, Simon. “The NAACP, Black Power, and the African American Freedom Struggle, 1966–1969.” Historian 69, no. 1 (2007): 49–82.

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Chronicle

The Black Vanguard

The Crisis

The Fifth Estate

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (Cornell University Press, 2017)