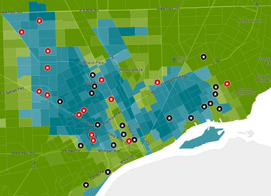

Police Homicides + Shootings 1968-70

The Detroit Police Department officially acknowledged that its on-duty police officers killed 42 civilians between 1968 and 1970 (see here and here). There is no publicly available list of the identities of the people killed, except for incomplete media reports at the time based on DPD disclosures to news reporters, meaning that in most cases only the police version of events is part of the public record--if the incident made the papers at all. The DPD only publicized the aggregate data of total police-involved "justifiable" homicides because of a onetime decision to make it part of a 1970 officer recruitment pamphlet, as explained below. The real number is certainly higher. Our project has identified 18 of the 42 acknowledged on-duty DPD police homicides during this time period, as well as three additional killings by off-duty DPD officers, all documented in the map below.

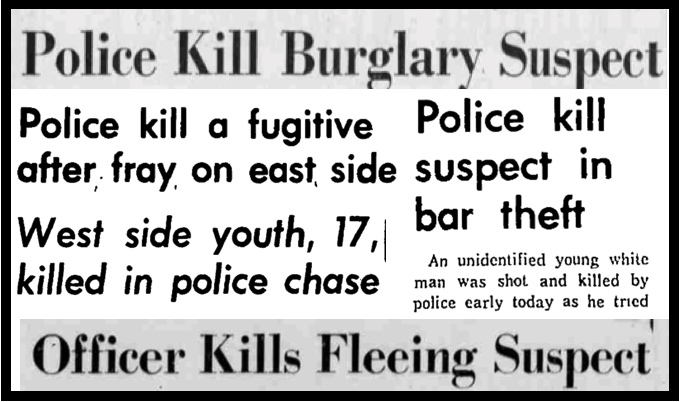

Most of the civilian fatalities identified by our team through archival and newspaper research involve unarmed African American male juveniles or young adults in their early 20s who were allegedly fleeing from the scene of a property crime and shot from the back. Almost all non-fatal police shootings identified here also fit this pattern, including several involving young white males. The killing of "fleeing" juveniles and young adults involved in nonviolent property crimes had made up the main category of police-involved homicides earlier in the decade as well, but the number of incidents escalated significantly in the racially targeted, get-tough, often openly racist police crackdown on African American youth in the late 1960s. The percentage of Black males killed by the police also increased substantially during this period. Between 1964-1966, almost half of the identified homicides were of white males with criminal records, most engaged in armed robbery. Most DPD homicides during the 1967 Uprising were of unarmed African American males, and this pattern continued during the 1968-1970 period, as detailed below, and then escalated even further during the STRESS era of the early 1970s. It is revealing that a majority of the identified homicides and non-fatal shootings between 1968-1970 and also during the STRESS era occurred along racial boundaries and commercial corridors, demonstrating a police deployment policy to protect white-owned property along the shifting color line with fatal force rather than simply to intervene with militarized force in the poorest Black neighborhoods.

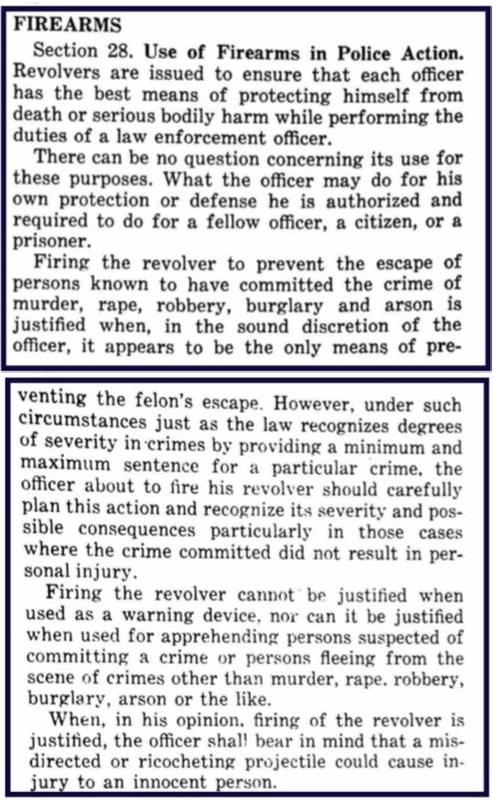

Liberalizing Use of Deadly Force Regulations

The Detroit Police Department made a deliberate decision to liberalize its "Use of Firearms in Police Action" policy almost immediately after the 1967 Uprising, when DPD officers shot at many African American civilians and killed at least 22 people, mostly unarmed alleged "looters." The previous policy, as revised in 1962 by a liberal police commissioner hoping to reduce fatal force against unarmed youth, instructed officers to fire on felony suspects only in "extreme cases" and permitted deadly force "to apprehend or prevent escape of a known felon . . . if the perpetrator cannot be apprehended by any other means." This policy, which was operative from 1962 through August 1967, also stated that: "The officer should not fire upon a person who is called upon to halt upon mere suspicion and who, without resisting, simply runs away to avoid arrest. Neither should the officer fire at a person who is running away to avoid a minor arrest." (Read the full policy for 1962-1967 here).

The revised "Use of Firearms in Police Action" policy (right) went into effect on Sept. 1, 1967, and remained operative until the mid-1970s, ushering in an era when the DPD probably killed more civilians per capita than any other urban police department in the United States. The revised policy stated:

The revised policy, for the first time, explicitly located authorization to use deadly force in the "discretion of the officer," part of the broader nationwide movement in the late 1960s to anchor the legal authority for get-tough policing in the individual discretion of the officer on the street, which also made it much harder to second-guess what the officer claimed happened in administrative reviews, criminal proceedings, and civil litigation. The revised policy also explicitly added robbery and burglary to the list of felony crimes for which the officer was authorized to shoot fleeing suspects and removed the previous manual's language that the officer must have personally witnessed ("if the officer actually sees") the crime take place. The revised policy further removed the previous language that "the officer should not fire upon a person who is called upon to halt upon mere suspicion."

Escalating Police Violence through Policy. The liberalization of the "Use of Firearms" policy was part and parcel of the racially targeted crackdown on Detroit's Black neighborhoods after the 1967 Uprising and had deadly consequences on the streets. Using official data, the DPD acknowledged fatal use of force against civilians in 22 cases during 1964-1966, the three years before the Uprising, and in 42 cases between 1968 and 1970. Half of the police homicides between 1964-1966 were of armed or allegedly armed civilians, whereas the vast majority of fatal force incidents between 1968-1970 involved unarmed and often fleeing 'suspects.' The DPD's policies, delegating more discretion to individual officers and encouraging a racially targeted crackdown on street crime in commercial districts and property crime that spilled over into white neighborhoods, therefore played a direct role in doubling the number of civilians killed by police officers in the late 1960s compared to the mid-1960s. The DPD argued that this happened because of the dramatic increase in violent and serious crime during this period, but the patterns of police-involved fatalities do not bear this out. DPD officers were far more likely to shoot and kill younger juveniles and unarmed African American males in the late 1960s, and far more likely to use deadly force against fleeing suspects in lower-level nonviolent property crimes, compared to the mid-1960s:

- Only 2 of the 17 police homicides identified by our project between 1964 and 1966 involved teenagers (both in 1964), but 7 of the 19 on-duty DPD fatalities identified for 1968-1970 are in that category.

- About half of police homicides between 1964 and 1966 included civilians who shot at or allegedly threatened the officer or another civilian with a deadly weapon, but only 6 of the 22 homicides detailed on this page involved a civilian actively or allegedly threatening an officer or another person with a deadly weapon. More than half of the police homicides between 1968 and 1970 involved suspects fleeing on foot who presented no threat. It is likely that the ratio is even higher than what our project has been able to document, given that such incidents usually received minimal media coverage and therefore it is reasonable to assume that a significant number of the unidentified homicides that did not make the papers at all also involved fatal force against poor Black males involved in low-level property crimes. (This pattern dramatically escalated in the early 1970s).

The DPD designed the new "Use of Firearms" policy to crack down on crime, including low-level property crime, in the commercial corridors and along the racial boundary between Black and white neighborhoods (see map below). The policy insulated police officers from consequences as long as their use of deadly force was reasonable in their individual "sound discretion," which was an extraordinarily broad category. Under three different DPD commissioners during the 1968-1970 period, internal investigations cleared every police officer who used fatal or non-fatal force "in the line of duty," even in the sizable number of shooting incidents that violated or pushed the boundaries of the new rules and would have clearly violated the previous policy. (The DPD did conduct a more thorough internal investigation after an officer beat and then shot a white factory worker in an appalling and clearly criminal action, but exonerated him nonetheless, as recounted below). Justified fatal force findings included cases where police officers shot and killed youth suspects for allegedly stealing a pair of shoes and allegedly stealing clothing, based on the interpretation that a "breaking and entering" burglary was a felony crime, and other cases where so-called "suspects" just did not halt on command (note again the explicit removal of the previous prohibition against shooting people "on mere suspicion" after ordering them to halt). These are all still only the technical legal rationales; the main reason for the consistent outcome of justifying police homicides was that the DPD chain of command retroactively classified all police actions that violated or strained its use of force policies as justified based on the prevailing law enforcement doctrine that police discretion in the field should not be second-guessed and that criminal law did not apply. This, as historical patterns documented in previous sections make clear, was nothing new.

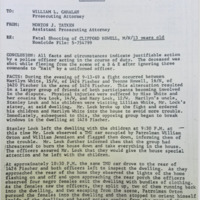

Prosecutorial Role in Justifying Police Violence. Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan found every police homicide of a civilian during 1968-1970 to be "justifiable," including in multiple cases where police fired at young juveniles in murky petty theft scenarios, except for one egregious case involving a white man brutally assaulted and murdered in front of multiple witnesses. (Even in this case, the prosecutor did not press formal charges but just took the case to a grand jury, which declined to indict). In the typical homicide scenario, if a police officer claimed to have yelled "halt," and if the officer claimed that the person killed was a suspect in a crime of any magnitude, the prosecutor automatically justified the shooting. The accounts by police in these cases are so similar--the officer yelled "halt," the suspect kept fleeing, the officer then fired--as to constitute a script that officers knew in advance would suffice. (Private security guards also killed five additional civilians in similar circumstances in 1970 alone, and the county prosecutor ruled all to be justifiable).

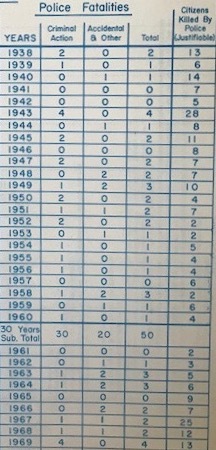

"A Good Time To Be a Police Officer?" In spring 1970, the DPD under Commissioner Patrick Murphy put out an extraordinary recruitment pamphlet designed to reassure potential applicants that it was "a good time to be a police officer" because they were far more likely to kill a citizen than to be killed by a criminal. The brochure also informed potential recruits that the Wayne County Prosecutor had habitually ruled such police homicides of civilians to be justifiable throughout the department's history (read the full pamphlet at right). The immediate context for the pamphlet was that seven DPD officers had been killed on the job between January 1968 and March 1970, included a white patrolman who confronted armed Black militants in the March 1969 New Bethel Incident (and whose partner likely fired first). Commissioner Murphy hoped to recruit officers to join the DPD by reassuring them that police work in the city of Detroit was not as dangerous as they feared, and by sending a message that the department and the local government would sanction their necessary use of deadly force. The pamphlet also included a statistical chart of "justifable" homicides by on-duty DPD officers from 1883-1969 (extracted here) that represents the only publicly available acknowledgment of this aggregate total that our project has been able to locate.

Commissioner Murphy warned the Detroit police to be vigilant against "armed assaults on police officers," although this was very uncommon. Murphy, who had a reputation as a reformer and was certainly less of a hardliner than his successor John Nichols, also urged police officers not to over-react and concluded:

Mapping Police Homicides and Shootings of Civilians

The map below documents 22 civilians killed by police officers in Detroit between 1968 and 1970. Three of these involved off-duty DPD officers, one involved the DPD but happened just across the boundary in the industrial suburb of Inkster, and one involved the Highland Park Police Department in a small municipality inside the city's boundaries. The 18 on-duty identified DPD homicides represent slightly less than half of the 42 acknowledged killings of civilians, which is itself inevitably an undercount. The 15 non-fatal police shootings also documented on this map represent an even smaller percentage of police use of firearms against civilians in this period. Academic studies have estimated that DPD officers shot and wounded civilians around 2.5 times as often as they killed them, which would mean approximately 100 non-fatal police shootings that actively wounded people during this three-year period.

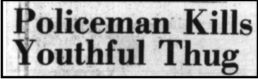

Three-fourths of the civilians whose race can be identified were African American, and one-third of all homicide victims were teenagers, almost all unarmed and fleeing from alleged nonviolent crimes. Also, more than half of identified non-fatal shootings were of unarmed and fleeing teenagers. Police use of firearms during this period was so common that many incidents barely qualified as newsworthy, if they did at all, with a few paragraphs taken directly from DPD reports buried deep inside the Detroit Free Press or Detroit News. In-depth coverage occurred only when the deceased was white, or very young, or when the family and community protested. The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's Black weekly, did provide more extensive reporting on several fatalities, but usually only after civil rights organizations or the family and friends of the victim forced the issue into public debate.

This interactive map locates police homicides and non-fatal shootings in the racial geography of Detroit based on the 1970 census. The darkest blue areas are all-Black neighborhoods, and the darkest green are segregated white areas, with the shifting racial boundary in between. Note how most shootings occurred along commercial corridors or in the racially mixed census tracts, not in the poorest and most segregated Black parts of the city. Hover over the dots to learn more about each incident and to see its source. Detailed statistical and pattern analysis is below the map, followed by a section providing case studies of each fatality.

- Black dots (22) = Police Homicides of Civilian

- Red dots (15) = Non-Fatal Police Shootings of Civilians

Police Homicides and Shootings of Civilians, 1968-1970, in Detroit's Racial Geography

Key Findings and Patterns

- "Justifiable Homicide" (100%). The Wayne County Prosecutor, William Cahalan, found every identified police homicide and non-fatal shooting to be "justifiable" during this time period except for one case involving a white victim, Charles Calloway. The prosecutor did not take a formal position but presented the case to the grand jury, which declined to indict.

- Race (79% Nonwhite). Almost all of the fatalities where race can be identified involved African Americans (14 out of 19), along with one Latino juvenile and three white adults.

- Gender (100% Male). All of the identified fatalities were of males, as were all those wounded in non-fatal shootings, except for one teenage female "runaway" shot when an officer fired into a car during a chase.

- Age (32% Teenagers). One-third (7 of 22) of the identified homicides involved teenagers or preteen youth, including three in the 9-to-14 age range. All but one were Black males who were unarmed and/or fleeing, also the scenario in almost all of the non-fatal shootings of juveniles. Most adults killed by police were Black males in their early-to-mid 20s.

- Unarmed (68%) and Fleeing (50%). Around three-fourths of the homicides (15 of 22) were of unarmed persons who posed no threat to the officer or another civilian when shot. Most of these (11) were of Black male teenagers or young adults who were suspects in minor property crimes of closed businesses late at night, fleeing from officers, and shot from behind.

- "Armed and Dangerous" (14% definite, 32% including alleged). Only 3 of the suspects killed by police were definitively threatening officers or civilians with guns, and only 1 of these actually opened fire. Several other cases involved civilians who allegedly had guns but were not self-defense situations.

- Domestic Disturbances and Mental Health Crises (18%). In 4 of the incidents, police officers responded to "family trouble" calls with extremely disproportionate force and killed people inside or near their homes. Two were unarmed and trying to run away when killed, one was unarmed and beaten to death by police, and the fourth was a tragedy involving an older man holding a fake gun.

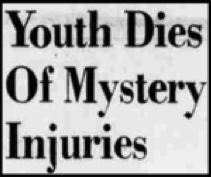

- Homicide by Beating (9%). Two of the deceased civilians, a 16-year-old Latino and a 23-year-old white man, were brutally beaten by police officers who instigated the encounters, as detailed below. The evidence in both cases indicates probable murders covered up DPD officers on the scene.

- Location. Police homicides and non-fatal shootings were disproportionately located along commercial and commuter corridors, such as W. Grand River, or in the racially mixed zones between Black and white neighborhoods. This indicates a DPD deployment policy to protect white-owned property (businesses and residences) along the color line rather than intensified police enforcement in the poorest, most racially segregated, and most allegedly 'high-crime' parts of the city, where almost all crime victims were African American.

Categories of Police Homicides. All 22 identified police homicides between 1971-1973 are featured in depth below. The first category covers 6 nonwhite teenagers or preteens killed by police; the second category analyzes 9 unarmed young adults killed by the DPD; and the third category features 7 armed or allegedly armed men who were shot and killed.

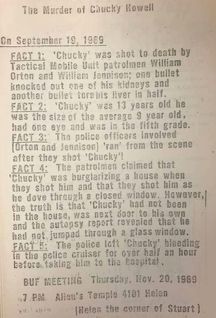

Category 1a: Chucky Howell, Age 13: Police and Prosecutorial Coverup

Clifford "Chucky" Howell, a 13-year-old African American male, was walking home from playing at a friend's house when a white Detroit police officer shot him from behind near his own backyard on the evening of September 13, 1969. The patrol team did not summon medical assistance for at least 40 minutes, and Chucky died later at the hospital. His father and local black power groups protested, but the DPD refused to allow them to examine the evidence. The Wayne County Prosecutor declared the homicide to be "justifiable" based on an indefensible and convoluted finding that "all facts and circumstances" supported the version of the officers on the scene.

The incident began when a white patrol team from the Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU) intervened on the side of a group of white youth during a dispute with Black teenagers in a poor West Side neighborhood that had recently been all-white but had become overwhelmingly African American during the past few years. The uncle of three white females requested assistance from TMU officers William Orton and William Jennison, who were driving by, and claimed that a group of Black females had injured his nieces in a fight. The uncle also said that the Black females had broken windows in the white family's house and threatened to burn it down. The uncle and the white youth allegedly left the scene, and the patrol team went to investigate.

The white officers claimed to see four Black females stealing "bundles of clothing" from the house of the white family and ordered them to halt. Whether this even happened is disputable, but by accusing the Black females of entering the white house to steal clothing in their incident report, the officers transformed the alleged offense to which they were responding from misdemeanor vandalism (breaking the windows) to felony burglary (breaking and entering), which had the convenient outcome of justifying deadly force.

According to the police officers, two of the Black females ran into their own house two doors down, and Patrolman Orton followed them inside. Orton claimed in his statement that he was disoriented in the dark house and then heard glass breaking as a "male figure" jumped through a rear window. Patrolman Orton claimed that he yelled "halt" and then fired three shots at the fleeing figure who was running down an alley, killing Chucky Howell. The Detroit News reported the police version that Chucky was part of a "neighborhood gang" that was terrorizing the white family. This was a racially inflammatory way to characterize the dispute between the females, and there is zero evidence that Chucky was involved.

At least five Black witnesses insisted that Chucky Howell was an innocent and oblivious bystander. Two of his older sisters, who were involved in the dispute, said that he was not there. Two other uninvolved Black teenagers said they saw Chucky cutting through the backyard coming home from his friend's house when a white policeman shot him for no reason, and that this happened almost an hour after the patrol team first intervened. They swore that Chucky began running away only after being shot in the back. An older Black woman said that the wounded boy made it to her porch before collapsing. All five of these witnesses told their stories to the Michigan Chronicle in its own investigation, because the DPD Homicide Bureau was not interested.

The logic used by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office to justify the fatal shooting of this 13-year-old child was outrageous and strongly indicates corrupt intent to participate in the coverup (left). The prosecutorial report labeled Clifford Howell a "fleeing felon," guilty of breaking and entering in the neighborhood dispute, even though there is no way from this sequence of events--this is obvious even from the prosecutor's cursory and biased memorandum--that Patrolman Orton could have known if the "male figure" had ever been inside the white family's house. The officer claimed that he saw "four negro females" exit the white family's residence, and then followed two of them into their own house, where he encountered a "male figure" and began shooting in the dark. By Orton's own statement, he did not witness Chucky Howell or any other male committing the alleged burglary, and so the shooting violated the "fleeing felon" standard even it if happened exactly as the officer claimed, which it almost certainly did not.

The prosecutor's memo did not contain any of the evidence that the Black eyewitnesses provided to the Michigan Chronicle except for an out-of-context excerpt that one of them had heard Patrolman Orton yell "halt." The memo did not acknowledge that the witnesses insisted that Chucky had not been escaping from inside the house when Orton shot him in the yard, or that the witnesses insisted that Orton yelled "halt" only after Chucky had been shot and started running away. There is no evidence that Patrolman Orton had any reasonable suspicion, much less the required direct knowledge, that the "male figure" had been involved in a felony, and so the prosecutor's application of the "fleeing felon" label was disingenuous and retroactive, a coverup that cannot apply to the officer's intent. (It is important to note that the prosecutor never intended the Clifford Howell "justifiable homicide" memorandum to be public; our project obtained the document from the archive of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, which had access to some law enforcement materials on the condition that they remain confidential).

Patrolman Orton's decision to shoot at Chucky Howell also clearly violated state law and the recently liberalized DPD policy (top of page), which stated that deadly force was only permissible against a "known" burglar if it "appears to be the only means of preventing the felon's escape." How could this apply to a group of Black teenagers who were being chased out of their own house by the armed officer himself, after a neighborhood dispute? Even if Chucky had been inside, where was a very small 13-year-old boy escaping to, where the officer would not have been able to find him later, rather than kill him? Even putting aside the racial element of the white officers intervening to protect the white family in a tensely integrated neighborhood by criminalizing their Black counterparts, the legal rationale by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office is indefensible, and so was the DPD Homicide Bureau's similar whitewash of the facts of the case.

Black radical groups got involved and disputed everything in the police account and prosecutorial exoneration of the white officers, Patrolman Orton and Patrolman William Jennison, whom they accused of murder of a completely innocent boy. The West Central Organization and the Black United Front, two Black militant groups based on the West Side of Detroit, held protests and also provided funds to the Howell family, which was very poor and had nine children. These community activists charged that officers had fled the scene of their crime, indicating culpability for killing a child, and failed to provide Chucky Howell with timely medical treatment. The Black United Front also contended, as the Michigan Chronicle investigation found, that Patrolman Orton had never been inside the house at all and had shot Chucky down in cold blood when the youth was not even aware of the danger and the situation.

Category 1b: Five Additional Homicides of Nonwhite Teenagers/Preteens by Police Officers, 1968-1970

Lester Earl Johnson (March 12, 1968). Johnson, an 18-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by DPD Vice Squad officer Terrance Les in a late-night encounter that began at a bar on Woodward Ave. Johnson allegedly offered to provide a prostitute to the undercover officer, and they headed toward a blind pig together in Les's car. According to the police officer, Johnson then pulled a gun and demanded his money. Terrance Les pulled out his gun and identified himself as a police officer, and Lester Johnson opened the car door and tried to flee. Office Les "immediately began firing" and emptied his six-shot revolver into the teenager, who died at the scene of multiple gunshot wounds. The incident did not make the mainstream newspapers; the Michigan Chronicle, the city's African American weekly, labeled Johnson a "thug" in a short report.

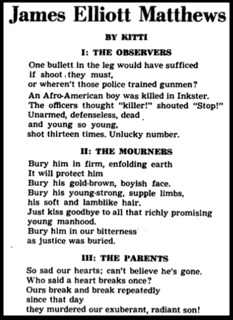

James (Jimmy) Matthews (Aug. 8, 1968). Jimmy Matthews, a 14-year-old African American boy and completely innocent bystander, was shot from behind and killed in the majority-Black industrial suburb of Inkster while fleeing from death threats made by a contingent of law enforcement officers from the Detroit Police Department, Wayne County Sheriff's Department, Inkster Police Department, and suburban Westland Police Department. The large group of officers was part of an intense manhunt for an African American man accused of shooting two Inkster policemen. There were many police abuses during the manhunt, during which law enforcement criminalized and racially profiled black youth in Inkster en masse, culminating in the death of Jimmy Matthews. Jimmy and three of his friends, all young juveniles, were talking outside a house at 3:00 a.m. when several white police officers jumped out of a car with rifles leveled at the terrified boys, who all ran. The police chased after them and found Jimmy running through a field in a residential area and shot him in the back as he fled toward his home. The Wayne County Prosecutor's investigation deliberately did not identify which officers fired, although the state ballistics lab could have done so, and said only that "17 officers flushed him out," as if the boy were a criminal fugitive. The officers involved were not charged after the prosecutor ruled the homicide a "case of mistaken identity," a dubious and concocted legal standard. Given the manhunt's search for an unidentified Black male fugitive, articulating the threshhold in this language indicates that the killing of any Black male in or near Inkster would be justified if the officers claimed they thought the person might be the target. Jimmy's older brother George called it a racial revenge killing: "an unwarranted assault on teenagers as a means to even the score for an act that was undoubtedly perpetrated by adults." Hosie Matthews, Jimmy's father, called for first-degree murder charges, filed a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, and said, "I think a frightened child might be captured without the use of firearms."

Fernando Gonzalez (March 25, 1969). Gonzalez, a 16-year-old Latino male who lived in Southwest Detroit, died after being beaten by multiple police officers and undergoing unsuccessful brain surgery. Four police officers responded to a "disturbance" call at a residence and encountered a group of youth, including Gonzalez, who had been drinking alcohol. The police claimed that Gonzalez "became belligerent," refused to get in the squad car when so ordered, and injured himself by falling. Multiple witnesses stated that the police officers beat Freddy Gonzalez with blackjacks, causing his injuries and eventual death. Gonzalez's father filed a formal complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission as well as the DPD's Citizen Complaint Bureau. The Committee of Concerned Spanish-Americans, a civic group in this heavily Latinx part of Southwest Detroit, also protested the police murder of Freddy Gonzalez. The Detroit Police Department cleared the officers and denied any brutality, stating that Gonzalez had injured himself and also put up "wild and uncontrolled resistance to the police." Mayor Cavanagh defended the police department.

Anthony Bullard (Oct. 30, 1969). Bullard, a 17-year-old African American male, was shot three times while fleeing by Patrolmen Albert Holman and Thomas Madsen. Bullard had allegedly broken into the home of his former girlfriend, violating terms of probation for an incident in which he had previously beaten the 16-year-old female. Her mother, fearing violence, called the police. Bullard fled when the police officers arrived and they shot him from behind, claiming to have yelled for him to halt. He was unarmed and posed no threat when killed.

Danny Smith (April 25, 1970). Danny, a 9-year-old African American boy and completely innocent bystander, was shot in the chest and killed by Patrolman Thomas Aranyos of the Highland Park Police Department around 10:30 p.m., while the fourth-grader waited at a bus stop with his mother. Patrolman Aranyos and his partner were chasing and firing at two suspected teenage car thieves who were running down a sidewalk in Highland Park, a small municipality inside the city of Detroit. The Highland Park Police Department initially claimed that none of its officers had fired the bullet that killed Danny Smith but refused to release the names of the officers involved in the chase. The state crime lab then determined that the bullet came from Patrolman Aranyos's gun. A few days later, 250 people marched from the scene of the fatal shooting to Highland Park City Hall to protest. The Wayne County Prosecutor exonerated the officers, because the shooting of Danny Smith was accidental--and also because Thomas Aranyos's intent to use deadly force against the two fleeing teenagers for the felony of car theft, no matter how dangerous in a crowded urban setting, was considered inherently justifiable under state law and police regulations.

Category 2a: The Unprosecuted Murder of Charles Calloway

Charles L. Calloway (Oct. 11, 1970). Calloway, a 23-year-old white male who lived in a working-class area of Southwest Detroit, was brutally beaten and murdered in his backyard by Patrolman Ronald Gedda, a white officer. Gedda and his partner, Patrolman William Freeman, claimed that they spotted Calloway and three other men in an alleyway (behind Calloway's home), told them to move a car, and asked for identification. The officers alleged that Calloway attacked them unprovoked and reached for both of their guns, prompting Patrolman Gedda to shoot Calloway through the heart.

Ten witnesses vehemently disputed the police account, and a Detroit Free Press investigation interviewed five people who all stated that the confrontation began when Patrolman Gedda called Charles Calloway a "smartass" and punched him in the face. After Calloway attempted to defend himself, Gedda brutally assaulted him in the alley for "at least five minutes" before his partner Patrolman Freeman said, "Why don't you shoot him and get it over with?" Gedda then fatally shot Calloway in the chest as the young man was sitting on the ground, dazed from the beating.

The extensive media coverage, and the fact that the incident involved a white unionized factory worker and military veteran, made this case unique. The DPD Homicide Bureau recommended a criminal warrant, and the Wayne County Prosecutor convened a grand jury inquiry rather than the usual predetermined exoneration process. (Notably, the prosecutor did not push to file charges, opting instead to ask the grand jury to investigate). The grand jury voted narrowly, 9-8, not to indict Patrolman Gedda. Several witnesses who testified or were scheduled to do so alleged that DPD officers had intimidated them, threatened violent retaliation, and in one case beat someone. The DPD's internal Trial Board later exonerated Gedda, despite the Homicide Bureau's report. The DPD decided to transfer the officer to a new precinct for his own safety, clarifying that this was not disciplinary but because "some of the people in the community believe he is a murderer."

Category 2b: Eight Additional Homicides of Young Adults Unarmed and/or Fleeing, 1968-1970

John Conley (June 6, 1968). Conley, a 27-year-old African American male, was shot in the abdomen and killed by Detroit Police Officer Leonard Sano when he tried to run away from the scene of an alleged burglary of an East Side supermarket.

William N. Morphew (August 10, 1968). Morphew, a 19-year-old white male, was shot and killed while unarmed and fleeing the scene of an alleged bar robbery at 4:28 a.m. in an all-white section of Northwest Detroit. Patrolmen Warren Quine and Richard Steel entered the premises to investigate and shot the youth three times in the chest. They claimed that Morphew ignored their orders to halt and struck one of them as he tried to escape. Morphew's death resulted in brief articles based solely on the police report in the mainstream Detroit newspapers.

George E. Smith (Aug. 25, 1968). Smith, a 22-year-old Black male, was shot and killed during a police stakeout of his scheme to con a family of a missing woman for the ransom money. Officer Kenneth Hady shot Smith in the lobby of his apartment building where he had told the woman's family to leave $25,000. When the officers emerged, Smith tried to flee the scene. Hady stated that he first fired warning shots and then shot him in the head. Hady alleged that Smith had a knife, but there is no evidence he threatened the officer. Smith had a criminal record and was awaiting trial on separate charges.

David Simpson (Aug. 30, 1969). Simpson, a 23-year-old African American male, was shot in the back and killed by Patrolman Gerald Boris while fleeing and after allegedly refusing to halt. Simpson had been involved in a bar fight earlier that evening and then, with his brother, drove to the home of the person he had tangled with and allegedly fired two shotgun blasts into the residence around 4:00 a.m. The police chased after Simpson and his brother, who jumped out of their car (without the shotgun) and fled on foot. Patrolman Boris shot David Simpson from behind, and the officers arrested his brother for attempted murder. At no time did David Simpson threaten the police officers with the weapon.

L. D. Johnson (Nov. 1969). Johnson, an African American male of unspecified age, was shot in the chest and killed by DPD officers responding to a domestic disturbance report that Johnson had shot his girlfriend in the hand. The police report said that Johnson fled and was struck by a police shotgun blast. Johnson's sister and other eyewitnesses disputed the police version and said he had stopped and turned around at their command to halt when shot and killed, and then the police falsely claimed that he had been threatening them. The family promised a civil lawsuit.

Richard Bryant (March 29, 1970). Bryant, a 20-year-old African American male, was fatally shot by Patrolman Thomas George while fleeing after allegedly robbing a party store of $75. The incident happened in a commercial district on the racial boundary between the African American West Side and adjacent white neighborhoods. Patrolman George said he ordered Bryant to halt and then shot him as he scaled a fence. Bryant had a starter pistol and the cash in his pocket when the body was recovered. The Free Press noted his death in a brief six-paragraph report.

Gerald Ostrowski (July 22, 1970). Ostrowski, a 22-year-old white male, was attempting to break up a knife fight when off-duty Officer Glenn Smith shot and killed him in a "tragic misunderstanding." Officer Smith was driving by when he noticed a knife fight on a porch close to Ostrowski's residence. When Officer Smith got out and detained the knife-wielding man, he was in plainclothes and Ostrowski, who also was trying to break up the fight, mistook Smith for an armed assailant and apparently "lunged" at him. Officer Smith then shot Ostrowski. Multiple eyewitnesses confirmed Smith's account.

Charles Neeley (Dec. 4, 1970). Neeley, a 25-year-old male of unidentified race, was fatally shot in the back on December 4, 1970, by TMU officer Patrick Little after allegedly stealing a pair a shoes from an apartment building. As Neeley ran away, the police officer fired five shots and hit him with one. The incident happened in a racially mixed, majority-white part of Southwest Detroit.

Category 3: Seven Police Homicides of Armed or Allegedly Armed Men, 1968-1970

George Carter (Aug. 8, 1968). Carter, a 42-year-old Black male, was fleeing and not actually armed when shot in the back, although the police officer claimed that Carter had been drawing a weapon when shot from the front. Patrolman Lawrence Ferger of the Narcotics Squad killed Carter during an arrest attempt for dealing heroin. The police unit was operating on a tip from an informant and claimed that Carter discarded bags of heroin as he fled. The police report stated that Carter turned toward the officers and put his hand into his shirt, as if to draw a gun. This was a fabrication, as the medical examiner report revealed that Carter had been shot in the back, which an eyewitness also confirmed.

Charles Raymond Mayse (Oct. 3, 1968). Mayse, a 31-year-old male of unidentified race, was shot in the chest by an off-duty white police officer while attempting to rob a bar on the outskirts of Detroit's East Side with a .22 pistol. Officer Ralph Schuster stated that he identified himself and ordered Mayse to drop his weapon. Schuster claimed that when Mayse turned toward him with a gun, the officer shot him twice.

Harrison Ward, Jr. (Nov. 16, 1969). Ward, a 27-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by multiple DPD officers inside his home after a high-speed car chase. Police claimed that Ward ran into his home and grabbed a gun and fired shots before they opened fire.

Milton G. Travis (Jan. 4, 1970). Travis, a 21-year-old African American male, was shot to death by Patrolman Hugh Patterson after Travis allegedly pointed a gun at the officer. Travis was enlisted in the U.S. Army and had deserted. He was with a 20-year-old Detroit man, and narcotics were late found in their car. But the officers pulled them over because the car apparently matched the description of one used for a getaway in a recent Inkster shooting. Asked for identification, Travis allegedly put his hand in his pocket and pulled out a pistol, leading Patterson to shoot him twice.

Darrel Banks (March 3, 1970). Banks, a 35-year-old Black male, was shot to death by off-duty DPD officer Anthony Bullock, who claimed that Banks allegedly assaulted a woman he was dropping off after a date. Patrolman Bullock stated that he ordered Banks to leave the woman alone, and Banks pulled out a .22 revolver, so Bullock shot him in the neck. The situation appeared to be a romantic quarrel as the woman was "trying to end" a relationship with Banks at the time.

James Webb (Aug. 3, 1970). Webb, a 56-year-old African American male, was shot inside his home by Patrolman Eric Rabone during a possible mental health situation. Officers arrived at Webb's residence after receiving a complaint that a man had pointed a gun from an upper window. Webb was actually holding a gun that could only fire blanks. The officers stated that they told Webb to drop the weapon, but he allegedly pointed it at Rabone, who killed Webb with a single bullet to the chest.

Robert Reese, Jr. (Dec. 3, 1970). Reese, a 35-year-old male of unidentified race, was shot and killed by Patrolman Thomas Warning during a holdup attempt of a gas station after either Reese or one of his companions, Roy Davis and William Thomas, opened fire and killed Patrolman Joe Souillere, Warning's partner.

In addition to the "Detroit Under Fire" team, Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab researchers Zev Miklethun, Madie Turner, and Caroline Levine contributed research for this page and identified some of the homicides documented here.

Sources

Citations for incidents mapped, including newspaper articles, are in the pop-up boxes. Additional Free Press, Detroit News, and Michigan Chronicle articles also used in reconstructing these cases.

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1967, 1970 update), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

James H. Lincoln Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Chucky Howell: Michigan Chronicle, Oct. 4, 11, 1969; Detroit News, Sept. 15, 1969

Michigan Chronicle, Aug. 24, 1968

Detroit Free Press, Aug. 10, 1968, Dec. 25, 1969, Dec. 27, 1970

Detroit News, March 21, 1969

John Wesley Domm, "Police Performance in the Use of Deadly Force: An Analysis and a Program to Change Decision Premises in the Detroit Police Department" (Ph.D. diss., Wayne State University, 1981)