Veterans Memorial Incident

The night began as a celebration. On November 1, 1968, 110 police officers were attending a dance organized by the Detroit Police Officers Wives Association on the first floor of the Veterans Memorial Building in downtown Detroit. At the same time, the Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church was holding a teen dance on the sixth floor. However, the Veterans Memorial Building had an architectural problem: there were not enough restrooms. The main bathroom was in the basement, and racial tensions began to build throughout the evening as off-duty white officers who were drinking alcohol constantly confronted the black church youth in elevators, stairways, and restrooms.

Drunk white men, most in their 30s, began to accost and abuse African American teenagers as both groups headed to the basement to use the men's room. (It is not clear in the following accounts at which points and to what extent the black teenagers initially realized that all of the individual white men who confronted and attacked them were police officers).

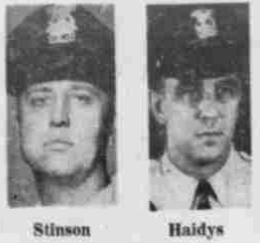

Patrolman Richard Stinson stopped Derrick Tabor and Greg Parker in the stairwell and yelled, "N-----s, what are you doing here?" According to a Detroit Free Press investigation, the same officer later questioned Grady Stallworth and Tommy Venable as they headed for the cafeteria, asking "What are you looking for, boy?" When Grady Stallworth took offense to the use of 'boy,' widely known to be an expression of racial disrespect, Stinson replied, "What are you looking for, n-----?" Another officer grabbed Tommy Venable, called him a "n-----," and swung at him. (Derrick Tabor and Grady Stallworth later picked Stimpson out of a police lineup).

During this exchange, which happened after midnight, Patrolman Stinson began to push Grady Stallworth toward the building's exit. (Grady had not realized that Stinson was a police officer until he saw the revolver during this confrontation). As the struggle continued, more black teenagers and inebriated white officers gathered. Stallworth's friend Tommy Venable, who was also being pushed out of the building and who already had been attacked by a white officer, then punched Patrolman Stinson and broke his nose. A white woman who was in the lobby ran upstairs and told the large number of officers in the ballroom that the youth were "beating up a policemen," and dozens rushed downstairs.

The situation immediately spiraled out of control. A number of white officers began chasing after the teenagers, waving guns, and one officer fired a shot at Grady Stallworth. Alll of the African American youth began running for their lives, with the officers running after them in aggressive pursuit. Each teenager has a different horror story from what happened next that night.

Accounts of the African American Teenagers

Grady Stallworth, 18, was chased by between 15-20 white officers after the initial confrontation described above. In his official complaint to the DPD, Grady said that all of them appeared to be drunk. Grady was running toward his parked Mercury Cougar, joined by his friend Jimmy Evans, but they tripped over each other and fell down. A white officer, whom Grady later identified as Sergeant Gerald Biscup, caught up to them, pulled his revolver, and said, "Come on. I'll take both of you." The teenagers ran in different directions, and the officer chased after Evans. Another officer yelled at Grady to halt and then fired a shot at him. He was convinced that he was going to die that night. Grady escaped and later--accompanied by his father, along with his brother who was also involved--filed an official complaint at 2:45 a.m. at the downtown DPD precinct (left).

Jimmy Evans, 19, was waiting for Grady Stallworth at Grady's car when he witnessed the confrontation and saw several white men with guns drawn chasing his friend. He went to help but then started fleeing with Grady when they fell down and Sergeant Biscup pulled a gun on them and said, "Come on. I'll take both of you." Evans ran toward the Detroit River with Sergeant Biscup in pursuit. The officer fired a shot at Evans, but missed. At least three other officers joined the chase. Evans tried to jump over a fence and an officer fired, hitting the metal. Jimmy Evans considered jumping into the river to escape but made an existential calculation that "it would be better to get shot than drown." The gun-wielding officers caught up to him and one of them, whom Jimmy later identified as Leo Haidys, smashed him in the face with a pistol. The others began beating him on the face and body and then kicking him on the ground. Some "were so drunk they couldn't hit me." The officers eventually kicked Jimmy Evans into a gutter and one yelled, "Get down there, n-----. That's where you belong." Evans pretended to pass out, and the officers laughed as they walked away. The DPD official report (right), taken at 1:30 a.m. that morning, omits almost all of these incriminating details, which only came out in later investigations.

Bruce Stallworth, 17, Grady's younger brother, witnessed the initial DPD attack on Grady Stallworth and Tommy Venable and was also shoved out the exit door by the white officers. Bruce ran to his father's car (his father was chaperoning the dance) with Cynthia Jones, 16. Nine or ten white officers surrounded the car, and one pulled a gun and told them to get out. The officers then began kicking the car and jumping up and down on the roof. Eventually they left, and Bruce and Cynthia then went to provide assistance to Jimmy Evans, whose beating they had witnessed (above left).

Derrick Tabor, 17, and his friend Greg Carter, 16, left the Veterans Memoral Building before the first physical confrontation, after suffering extensive abuse and repeatedly being called "n-----" by drunk police officers in the basement and elevator. From outside, they witnessed the police attack on the group of black youth and the shot fired by Sergeant Biscup at Jimmy Evans. They ran for Greg's car, with white men in pursuit, but Greg was so terrified that he did not unlock the passenger door. Before Derrick could get inside, a gun-waving police officer, whom they later identified as Sergeant Biscup, began menacing the teenagers and threatening to shoot. Then another officer, later identified as Patrolman Leo Haidys, yelled at Derrick to get out of there or be shot, and so Derrick ran to the riverfront with about six or eight white officers chasing close behind. At this time, Greg drove away. Derrick stopped after the officers told him to halt or be shot. Either three or four of the officers then beat him in the face and body and kicked him as well. At one point they dragged Derrick into the bushes and assaulted him some more. They said, "you had enough yet, n-----?" After they left, Derrick Tabor began walking home and Greg Carter found him and gave him a ride. Derrick told what happened to his father, a Presbyterian minister, who immediately drove him back to Veterans Memorial to report the incident to the police, but they did not want to take his statement. While back at the scene, Rev. Tabor witnessed several of the involved police officers who were almost too drunk to stand. He then took his son to the nearby precinct station to file a formal complaint, after which Derrick went to the hospital for his injuries.

Black Protests and Modest Police Discipline

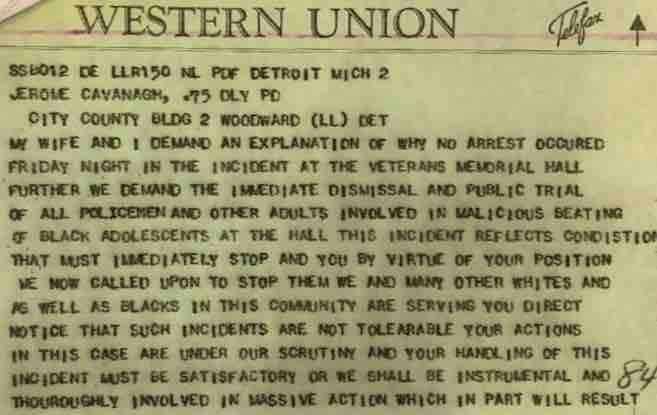

The Veteran's Memorial Incident sparked outrage from African American politicians, civic leaders, and many other citizens in the city of Detroit. State senator Coleman Young, a prominent critic of the DPD, demanded the immediate firing and criminal prosecution of the officers in a telegram to Mayor Cavanagh (right). Young warned of massive protests in the streets if the DPD and Cavanagh administration did not take action.

Coleman Young arranged a follow-up meeting with the mayor and black leaders, including Reverend Stephens, the pastor of the A.M.E. church that sponsored the Veterans Memorial youth dance. Stephens informed the mayor that the church youth had been terrorized and that "a policeman with a gun is dangerous when he's sober." Young charged that the Cavanagh administration had lost control of the police department and that the DPOA union combined with the DPD hierarchy were actually running the city and impervious to democratic authority. U.S. Representative John Conyers said the DPD was "infested with white racists." Other civil right rights leaders said that black Detroiters were living in a police state and called the DPD the "shock troops for Wallace and fascists," a reference to the recent attack by DPD officers on leftist protesters at a George Wallace presidential rally. The delegation demanded black commanders in the nonwhite precincts, mass hiring of African American officers, and civilian control over the police department. They strongly accused Mayor Cavanagh of sending the message that police brutality would not be punished (below left).

The DPD did not initially arrest any of the white officers despite multiple victims filing formal complaints effectively accusing them of felony assault, attempted murder, and assorted other crimes. And not surprisingly, the "Blue Curtain" held strong and none of the officers present filed reports or later testified against the large number of policemen who had broken multiple felony laws that night. But under sustained pressure, DPD Commissioner Johannes Spreen did suspend nine of the officers involved, and he authorized a police trial board investigation led by Superintendent John Nichols. This was an atypical move for Commissioner Spreen and represented the only significant specific action, beyond rhetoric and promises, that he took against police brutality during his year-and-a-half in charge. The commissioner only suspended a fraction of the officers actually involved, although in fairness it was difficult for investigators to identify all of the individual off-duty officers who took part that night, especially because of the police code of silence. It is also relevant that the African American youth victims were from "prominent families," as the Detroit Free Press observed.

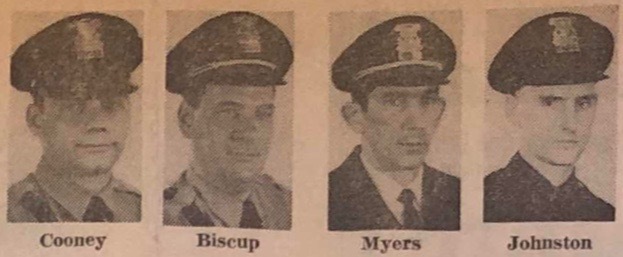

The DPD trial board found four officers guilty of violating departmental rules and regulations. The trial did not consider whether any were guilty of physical assault or unauthorized use of service weapons, for drunkenly firing guns at unarmed youth on a downtown plaza. Patrolman Patrick Cooney, Jr., was fired for "mistreating" a citizen, Sergeants Gerald Biscup and Thomas Myers were temporarily demoted to patrolman for submitting improper reports, and Patrolman James Johnston received a brief suspension without pay. Civil rights and anti-police brutality groups criticized the minimal punishments and argued that the mayor's office had an incentive to downplay what really happened because the same city attorneys who argued the trial board case against the officers had responsibility to defend them against civil lawsuits.

The DPD also referred Patrolmen Richard Stinson and Leo Haidys, Jr., for prosecution on criminal assault charges, an almost unheard of development. The trials of Stinson and Haidys were moved to a small rural town south of Lansing because DPOA union lawyers argued that the "publicity," meaning black jurors in Detroit, would not give them a fair hearing. A white jury acquitted Haidys, accused of smashing Jimmy Evans in the face with his revolver. Multiple police officers testified that Evans and the other black youth had attacked them, unprovoked. After this, the Wayne County prosecutor dropped the charges against Stinson, stating that the teenagers could not reliably identify which specific off-duty policemen allegedly had assaulted them.

Carl Parsell, the head of the Detroit Police Officers Association union, pushed a conspiracy narrative after the Veteran's Memorial Incident. He blamed the African American youth for the attack, falling back on a historically racist trope by claiming that officers were simply defending their wives from "obscene gestures and remarks" by the black teenagers. Parsell said that "any man, when provoked, would have done what the men did." He also said Patrolman Stinson "politely" asked the black youth to leave because they were bothering people, and then was assaulted unprovoked.The DPD's own investigation repudiated these DPOA lies and found that "no policeman or wife has come forward with first-person accounts of harassment." Parsell then accused the DPD of suppressing evidence to achieve findings of guilt because of black political pressure and floated the absurd claim that the black youth had exercised "silent intimidations" on the white women. After the verdicts, the DPOA lawyer called it "the greatest injustice ever to come out of a trial board hearing" and said the white officers had been "scapegoats" to satisfy the outcry in the black community.

The results of the police trial board were in reality quite modest, given that between one and two dozen police officers had committed felony assault and several had committed attempted murder of unarmed teenagers. But still, the verdicts against four officers, even for minor infractions, were groundbreaking given that the DPD almost always covered up and justified incidents of brutality and misconduct. It is very likely that the main reason for this divergent outcome was that the officers were off duty and inebriated when they brutalized African American youth, rather than doing so while on patrol in the streets, where the DPD and the Cavanagh administration always upheld their discretionary authority. The indiscipline shown by off-duty officers, and the terrible media coverage that resulted, came at the very moment that the DPD was launching a public relations campaign to change its image. DPD advocates of police professionalism and enhanced police-community relations could not simply ignore such egregious misconduct, although they generally categorized what happened as a violation of department rules rather than as crimes. After the trial board hearings, Commissioner Spreen announced the punishments and called the actions of the guilty officers "unprofessional, uncalled for, and inexcusable."

However, over the next two years, the city government and DPD gradually reduced or lifted most of the punishment against the police officers. The DPOA's aggressive legal defense of officers charged with misconduct, and recently established due process protections for such officers, also played a key role in these outcomes. A local judge reversed the trial board finding against Patrolman Johnston. The DPD reinstated Leo Haidys after his acquittal, and Richard Stinson after the prosecutor dropped the charges.

In the most striking development, Mayor Cavanagh reversed the trial board demotion of Sergeant Gerald Biscup, who according to testimony had threatened the lives of terrified teenagers hiding in cars and fired his gun while presumably inebriated at one and probably several unarmed and fleeing youth. Biscup appealed the trial board decision as a case of mistaken identity, and if someone else besides him really had done these things, it is relevant that neither Biscup not anyone else behind the "Blue Curtain" revealed who it was. In August 1969, eight months after the Veterans Memorial Incident, Cavanagh ordered full back pay and restoration of rank to Biscup, claiming that the charges against him, which included testimony accusing him by three African American victims, were not substantiated. The mayor did acknowledge that "represensible and criminal acts were committed" against the teenagers, but said that their testimony about which officers had done so was "tenuous or discredited."

How is it possible that the DPD only fired one police officer after a violent and racist mob-style mass attack on teenagers, and that only one of the dozens of white men involved was prosecuted at trial? It is important to emphasize that what activists labeled "police brutality" and "police misconduct" also represented police illegality, criminality, and often felony wrongdoing. By creating a system in which criminality by police officers went unpunished, or at most received mild discipline as a violation of DPD "rules and regulations," the police department had become one of the largest and most well-organized, and certainly the most legally untouchable, criminal organizations in Detroit. The Mafia-style "Blue Curtain" also made the discipline and prosecution of police officers who committed crimes almost impossible, on the few occasions when the DPD actually tried. Mayor Jerome Cavanagh's insistence that the Detroit police department could still police itself, along with the white majority's support for DPD autonomy and discretionary brutality against black citizens, allowed these patterns of police criminality to continue to intensify without consequence.

Sources:

Detroit Historical Society Online Collection

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

William Serrin and Clark Hoyt, "Participants in Vet Memorial Incident Tell Story," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 26, 1968

Detroit Free Press, Jan. 21, 1969, Feb. 3, 6, 1969, March 5, 1969, August 18, 1969, Sept. 8, 1969, Feb. 6, 1970

Detroit News, Oct. 17, 1969