IN FOCUS: Fitzgerald's Infernos

Police harassment and brutality against African Americans in Detroit often clustered along shifting racial boundaries between black and white sections of the segregated city. The overwhelmingly white DPD consistently policed and regulated the color line, criminalizing African Americans rather than focusing on actual crime control, as the NAACP had demonstrated in its testimony to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 1960. The Michigan Civil Rights Commission's investigation of stop-and-frisk policing in Northwest Detroit confirmed that DPD officers continued to police racial boundaries a decade later, in particular by focusing on African American teenagers and young adults in or near areas understood to be "white." And often, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, police violence against black students accompanied racial tensions in recently integrated schools located in neighborhoods undergoing white flight and racial transition, as the previous page documented.

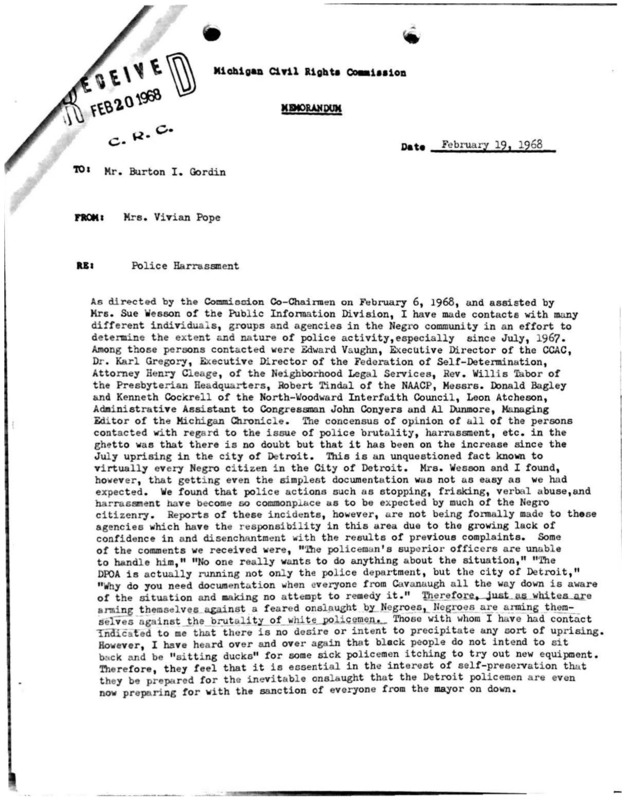

The story of police harassment and brutality against the Infernos during the late 1960s is an example of how the white-controlled DPD defended racial segregation not only through discretionary criminalization along the color line but by focusing intently on an entire region, Northwest Detroit, that was undergoing rapid demographic transition. Some of the worst police violence during this time period happened at Cooley High School in Northwest Detroit, where the black student enrollment rapidly increased from 15% to 50% in just two years. The nearby junior highs also experienced serious racial tensions and discriminatory police crackdowns, and so did an African American teenage club located in the Fitzgerald neighborhood of Northwest Detroit and called the Infernos.

Founding the Infernos and DPD Intimidation

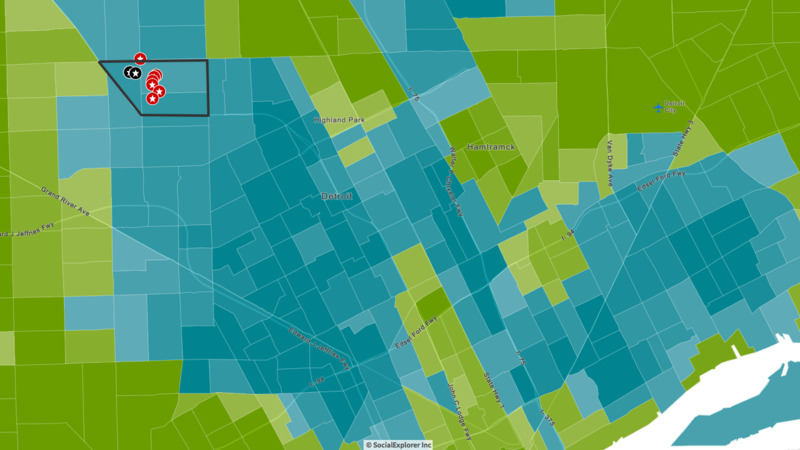

A group of nine female African American teenagers from Cooley High School founded a club called the Infernos in 1966 in their Fitzgerald neighborhood, a small, segregated black enclave surrounded by hostile all-white subdivisions in Northwest Detroit (see above map). The Infernos sought to create a sense of community for black teenagers and rented a space to create a youth center. To raise funds, the club held chaperoned dances for black youth at local churches. They took this step because the main teen dances held in that part of the city were restricted to whites only, and the owner of the ballroom refused to rent to their group. The Infernos raised a lot of money--some dances attracted 800 or more teenagers--and met with an architect to begin planning the center.

But then, in May 1967, St. Timothy's Episcopal Church suddenly barred the Infernos from continuing to use its facilities for dance fundraisers, under pressure from white parishioners. A Lutheran church denied them permission as well. Around the same time, a "merchant with a racist history," according to William Bunge's community study of Fitzgerald, asked local DPD officers to pressure the owner of the building to cancel the rent agreement with the Infernos for the youth center. As the Michigan Chronicle reported, the police "frightened the owner" with unfounded charges that the Infernos were trouble-makers and criminals.

The Infernos responded to the collapse of their youth center plans by starting another venture, the Infernoburger, and purchased a former hamburger stand at the corner of Puritan and Cherrylawn. Their goal was to open a restaurant to provide a hangout, and jobs, for local black teenagers. As they renovated the building, the Infernos went ahead and turned it into a teenage club, with a juke box and ping-pong table among the attractions.

DPD Crackdown on the Infernoburger Teens

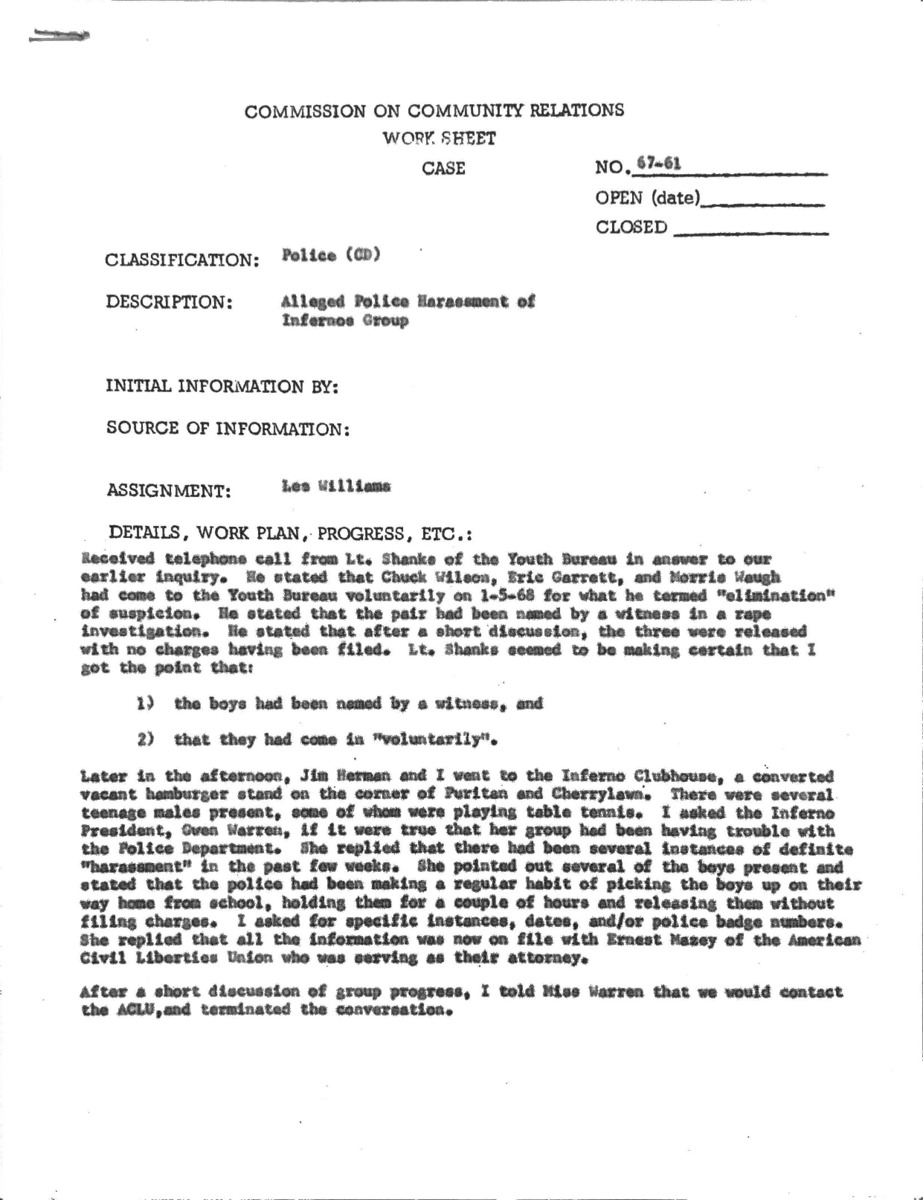

At first, the teenagers at the Infernoburger hangout developed a positive relationship with the local police, because the unit that patrolled that neighborhood was integrated. One African American officer, Mackie Johnson, lived only two blocks away and started playing ping-pong with the teenagers. But in December 1967, for unclear reasons, the precinct commander transferred the friendly black officers and replaced them with an all-white squad that immediately began to harass and intimidate the Infernos.

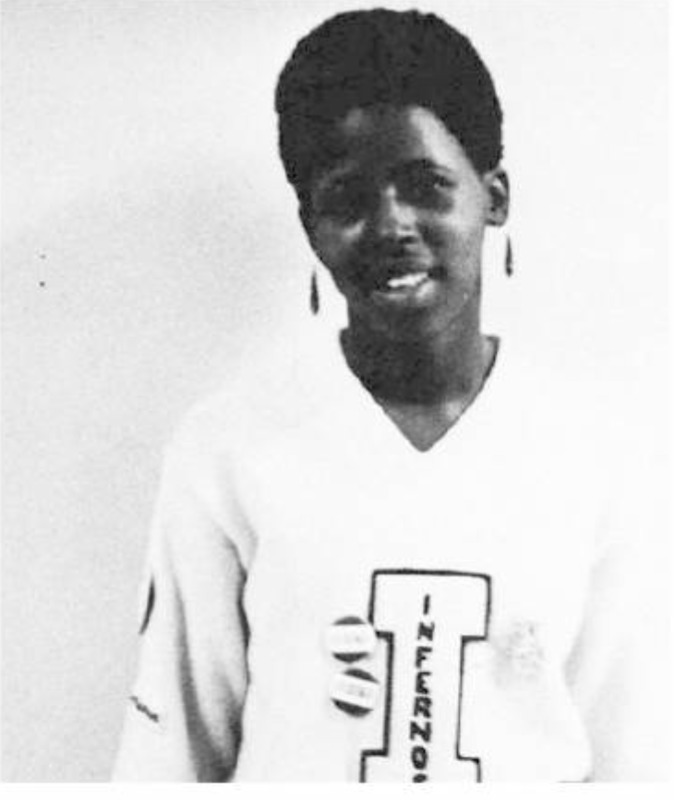

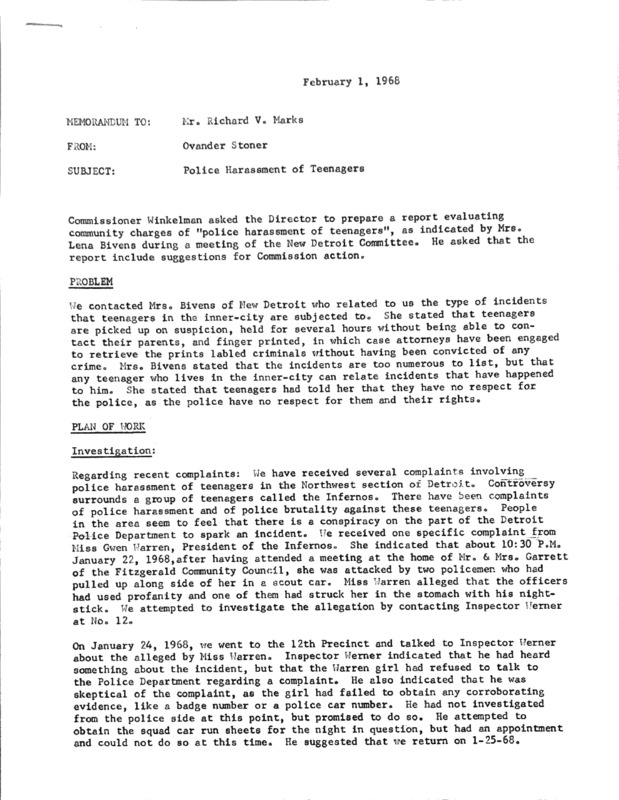

The newly assigned police officers began to stop-and-frisk the black youth in the Infernos club constantly. As the harassment and racial profiling escalated, a group of the Infernos, including club president Gwen Warren (right), filed an official complaint at the DPD's Palmer Park precinct sub-station. This action resulted in swift retaliation, as was so often the case when African Americans charged the DPD with brutality and misconduct.

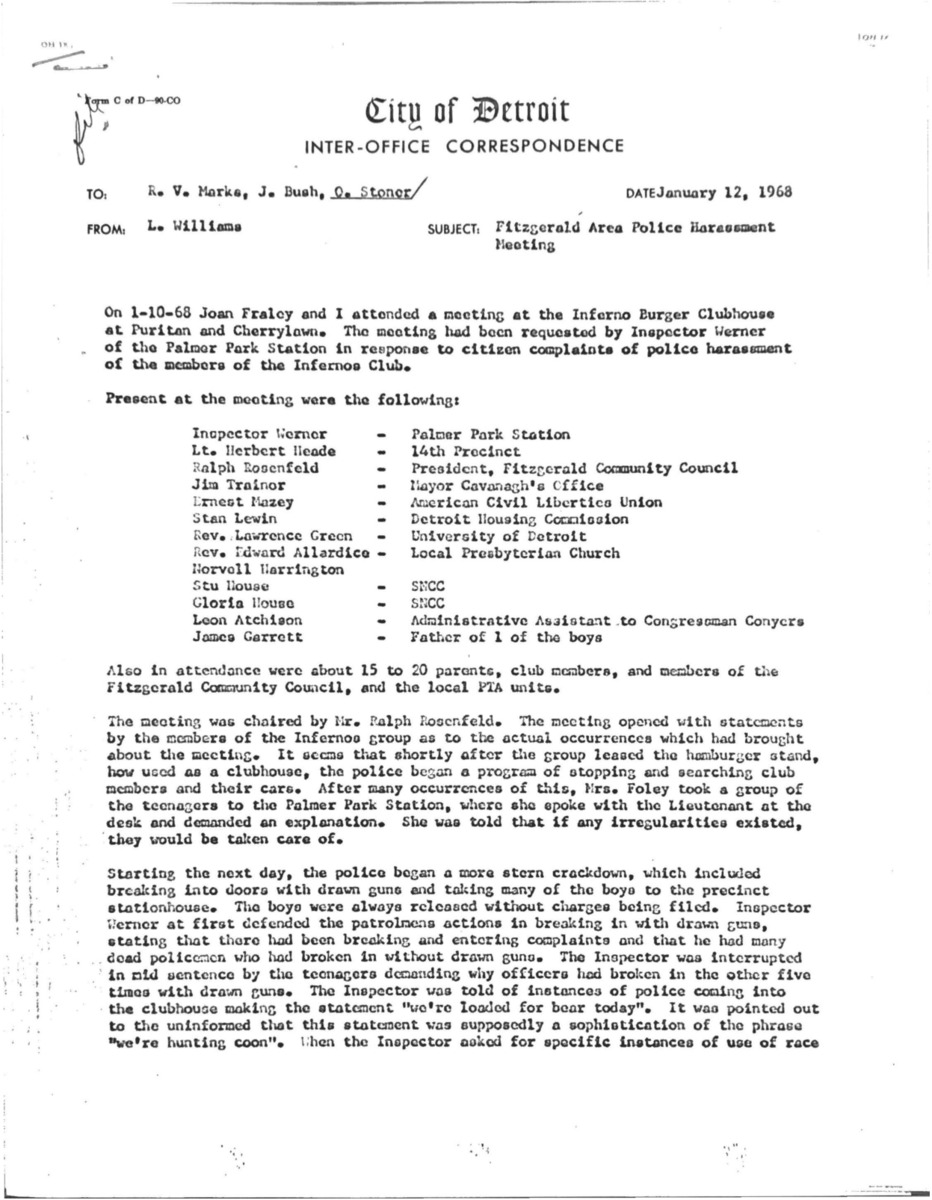

Two hours after the Infernos group filed the complaint, DPD officers stormed the Infernoburger with guns drawn under the false pretense that the black youth had been harassing white teenagers. One member of the Infernos described the scene:

The Palmer Park police squad conducted five more warrantless raids on the Infernoburger, with guns drawn, through the end of January 1968. The teenagers reported that white officers often shouted, "We're loaded for bear today."

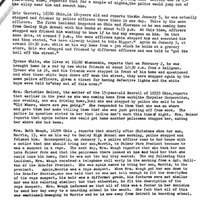

The DPD officers also began constantly stopping and frisking African American teenagers on the street, using racist language, accusing them of felony crimes, and taking them to the station under false pretenses. Eric Garrett, a 16-year-old affiliated with the Infernos, was a student at Cooley High School and his mother was head of the Fitzgerald PTA. During a single week, DPD officers:

- Jan. 4, 1968--DPD arrests Eric Garrett on false charge of suspicion of rape and questions him at 14th Precinct

- Jan. 5, 1968, at 4:15 p.m.--DPD stop-and-frisk of Eric Garrett on his way home from Cooley High

- Jan. 5, 1968, at 7:00 p.m.--DPD stop-and-frisk and verbal racist abuse of Eric Garrett on his way to work at grocery store

- Jan. 5, 1968, at 10:30 p.m.--DPD stop-and-frisk of Eric Garrett on his way home from work and told to "get the hell off the street"

- Jan. 9, 1968--TMU officers re-arrest Eric Garrett on false charge of suspicion of rape and question him at 14th Precinct

DPD officers from multiple precincts also launched a sustained campaign of abuse against Morris Waugh, a 15-year-old African American male who was part of the Inferno group that filed the initial harassment complaint on Dec. 26, 1967.

- Jan. 5, 1968--DPD stop-and-frisk of Morris Waugh on his way home from Cooley High (date estimated)

- Jan. 7, 1968--DPD officer from 12th Precinct informs Morris Waugh's mother that he is a suspect in a rape investigation and to bring him to the station

- Jan. 8, 1968--Morris Waugh and his parents go to station and are told he is not a suspect

- Jan. 9, 1968--DPD officer from the 14th Precinct calls the house and names Morris Waugh as a suspect in a different rape investigation, but then at the station officers tell him he does not fit the description

DPD officers patrolling the Fitzgerald area stopped and frisked many black teenagers during the winter of 1968 and also, on at least one occasion, explicitly enforced the color line by pulling over a car containing a 16-year-old black youth and two of his white friends and told the white teenagers to "stay out of this area." The Michigan Civil Rights Commission documented a number of these incidents and reported on the fear among black families. (View an interactive map of the incidents reported to the MCRC at the bottom of this page, and pattern analysis here).

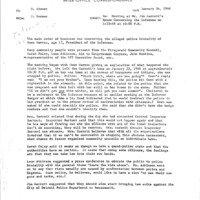

On January 10, after some of the harassed youth filed additional complaints, the Palmer Park police inspector and the 14th Precinct commander agreed to meet at the Infernoburger with around 20 club members and their parents, along with representatives of the ACLU, the mayor's office, and the Detroit Commission on Community Relations. The meeting did not go well. The police inspector defended his squad's actions in breaking into the Infernoburger with guns drawn, as a legitimate crime investigation operation, and denied that his officers had used racist language. And the response of the mayor's representative suggested either that the Cavanagh administration believed that the DPD needed to retain total discretion to crack down on black youth criminals and radicals, or accepted that the police were beyond its control, and perhaps both.

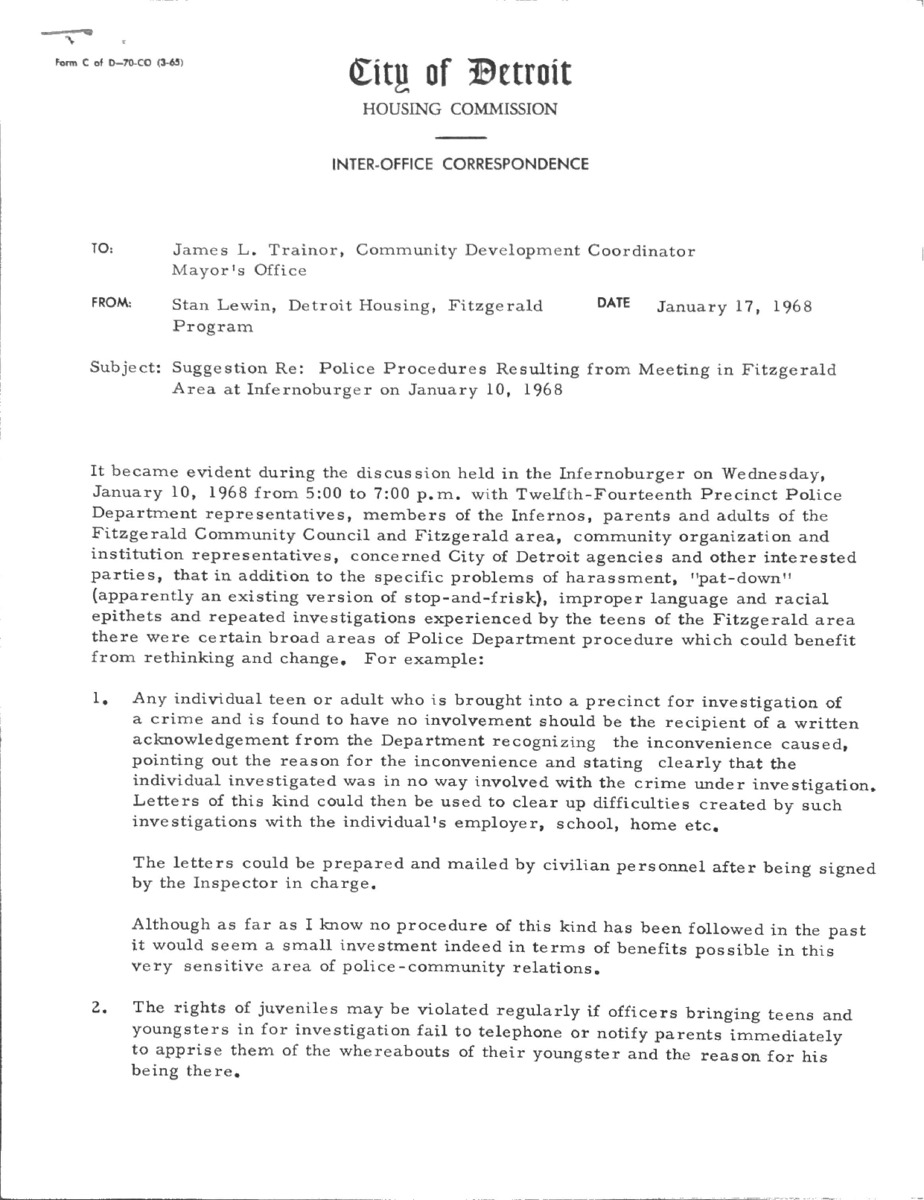

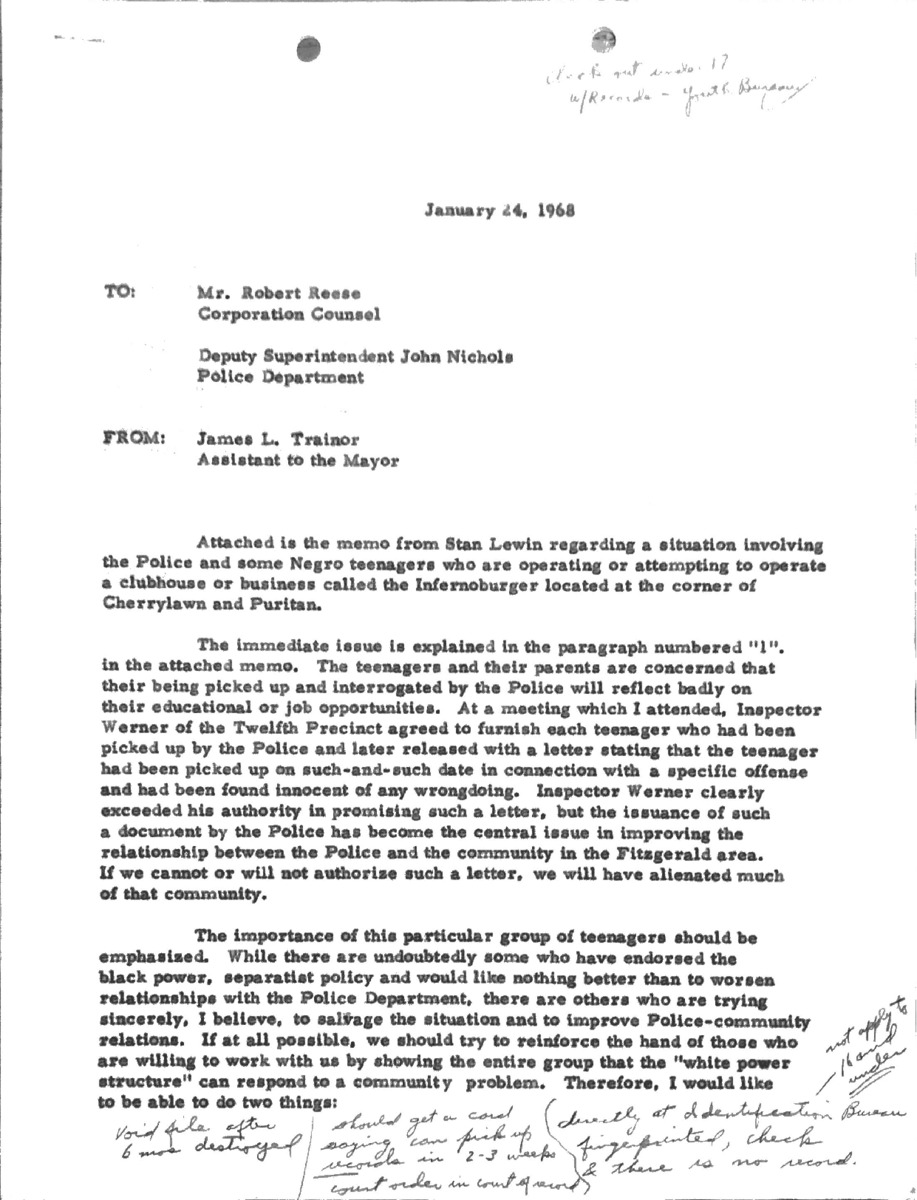

The Cavanagh administration, which was in the process of enacting a stop-and-frisk law, focused narrowly on proper police procedure rather than acknowledging the racial profiling and wrongful criminalization of innocent black teenagers. The mayor's office recommended that the DPD provide teenagers brought in on suspicion of rape an official acknowledgment if they were cleared of the charge and also reminded the precinct of its legal responsibility to notify the parents of detained juveniles promptly. (In effect, the mayor's representative accepted that Eric Garrett and Moses Waugh really were genuine suspects in rape investigations). In its memo to the DPD, the Cavanagh administration was particularly concerned that some of the Infernos "have endorsed black power," but also emphasized that the fair thing to do would be to clear their records so the arrests would not harm their educational and employment opportunities. The mayor's representative did suggest that Palmer Park officers receive human relations training on "the dignity of the individual," which was almost a caricature of the ineffectiveness of liberal reformism in the face of a coordinated campaign of racist harassment by multiple DPD precincts.

The DPD's Retaliatory Violence and Fitzgerald Community Outcry

Two white DPD officers assaulted 17-year-old teenager Gwen Warren, the president of the Infernos, at 10:30 p.m. on Jan. 22, 1968, as she walked home from a community meeting at the residence of her friend Eric Garrett. After one white officer called her a racist and sexist obscenity, and she stood up for herself, he beat her with a nightstick (e.g., felony assault). The officer then said, "If we don't get you this winter, we will get you this summer. Nobody is going to tell us how to do our jobs." This was a clear reference to the complaints of police brutality and harassment that the Infernos had filed previously, and therefore an illegal retaliatory threat.

DPD officers also later claimed that Gwen Warren and her group were attempting to "overthrow the police." This seems absurd, but there are several explanations. First, many DPD officers believed that civilian complaints of police harassment and brutality were an illegitimate infringement on their absolute right to exercise power on the streets. Second, Gwen Warren personally did not back down and submit to illegal police misconduct, and by her own account she mocked the white officer in the late evening encounter on Jan. 22. And third, it is likely that the DPD Intelligence Bureau had a file on Gwen Warren accusing her of being a black power radical, since her previous high school had forced her to transfer to Cooley (a high school where the Intelligence Bureau also illegally monitored black student activists) because she wrote for an underground publication and had submitted a paper about the black power movement for an English class.

Gwen Warren filed another official complaint, which took a lot of courage since her participation in the first one had resulted in the DPD's retaliatory campaign of Infernoburger raids, stop-and-frisk harassment, and illegal arrests of her friends. The 12th Precinct inspector denied that the incident had happened and said there was no evidence because the squad car log said the police had been elsewhere (as if this could not be doctored after a brutality incident) and because Warren had not seen the officers' badge numbers (the incident happened at night, and officers often removed their badges before such unauthorized encounters).

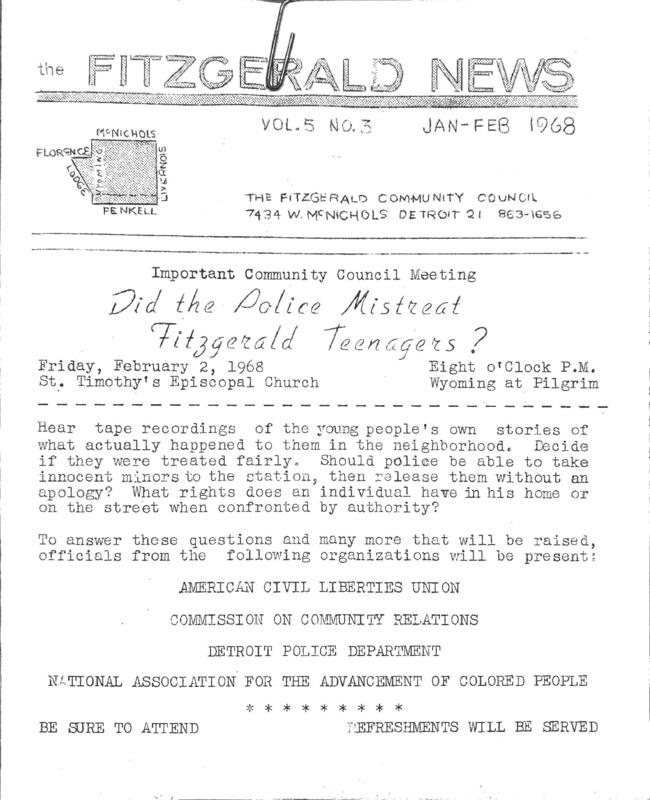

The DPD's racist and illegal harassment campaign, and especially the attack on Gwen Warren, created a massive outcry from African American residents in the Fitzgerald community. On Feb. 2, the Fitzgerald Community Council sponsored a public meeting that was also attended by the ACLU, NAACP, DCCR, and representatives of the Detroit Police Department. The gathering denounced the stop-and-frisk policies and wrongful arrests, as well as demanding removal of "officers who are sick with the disease of racism or sadism." At the event, parents and activists charged that that the DPD hierarchy had lost control of a faction of its white racist officers who were actively seeking to provoke another race riot.

Many parents in the room were also extremely worried by the bitterness expressed by Gwen Warren. According to the Michigan Chronicle, she said, "that policeman got me in the dark, and we'll get them in the dark. Just wait until next summer." Other adults present blamed this frustration by an African American teenager, who just wanted to start a community center for black youth in a racially segregated city, on her experience living in a "quasi-police state."

No police officer was ever punished for any of the attacks and harassment of Gwen Warren, other Infernos, or black teenagers in Fitzgerald who hung out at the Infernoburger. Assessing the situation, a field investigator for the Michigan Civil Rights Commission observed that the incidents documented in its inquiry (as previously detailed on this page) "are only a sampling."

Map of police brutality and misconduct against black youth in Fitzgerald, Dec. 1967-Feb. 1968, reported to the Michigan Civil Rights Commission

Sources:

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Note: some research on this page is drawn from other documents in Box 586 of the Cavanagh papers that are not reproduced here.

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

William Bunge, Fitzgerald: Geography of a Revolution (1971)