Mapping Police Killings, 1957-1963

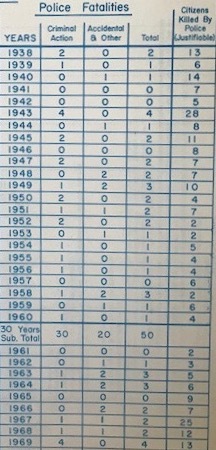

The Detroit Police Department acknowledged 28 "justifiable homicides" of civilians by police officers "in the line of duty" between 1957-1963 (left), which is likely an undercount. Our project has been able to identify 22 of these on-duty DPD homicides, plus two additional by off-duty officers and three more by other law enforcement agencies, through archival and newspaper database research.

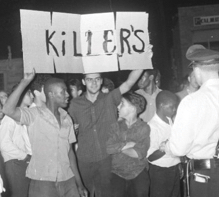

The DPD Trial Board and the Wayne County Prosecutor, responsible for the city of Detroit, exonerated all of the on-duty DPD killings of civilians between 1957 and 1963. Furious protests greeted several of these decisions, particularly in cases involving unarmed teenagers and the shooting of Cynthia Scott in the back, when multiple Black witnesses testified that she had been murdered. The only prosecution our project has identified was a "reckless use of firearms" charge against an off-duty officer who claimed that he accidentally shot a friend after a late-night party (he was acquitted).

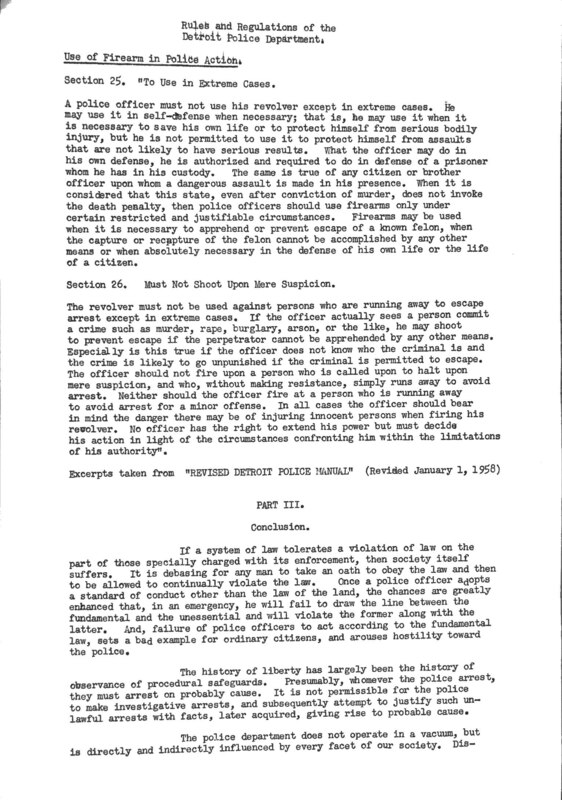

Before 1962, the Detroit Police Manual allowed officers to use deadly force against fleeing and unarmed suspects, even for alleged misdemeanor offenses. The DPD policy became more restrictive, at least on paper, in 1962 as part of the reform agenda of the Commissioner Edwards/Mayor Cavanagh administration. The new "Use of Firearms in Police Action" policy stated that police could use deadly force "to apprehend or prevent escape of a known felon," when no other alternative to capture existed, and that the officer must have personally witnessed the felony in order to "shoot to prevent escape." The felony category was still capacious, encompassing low-level nonviolent property crimes such as burglary as well as automobile theft, commonly committed by juveniles and often labeled "joy-riding." The DPD policy also stated that police officers should not shoot their revolvers at "a person who is called upon to halt upon mere suspicion" or "a person who is running away to avoid arrest for a minor offense" (see policy at right).

The DPD Trial Board and the Wayne County Prosecutor justified all fatal shootings by officers during this time period, even those involving juveniles who fled to escape apprehension for minor traffic violations and petty theft. This indicates a de facto policy of protecting on-duty police officers from criminal liability even when their use of fatal force stretched the boundaries of, or clearly violated, the policy and the law. Strategies for doing this included redefining nonviolent misdemeanor-level offenses as felonies under the discretionary authority of the prosecutor; emphasizing the felony nature of an offense (such as a stolen car) even when the unaware officer had only witnessed a traffic violation; and, in disputed cases, finding that the deceased civilian was armed, or perceived by the officer to be armed, and therefore made the shooting an act of self-defense.

27 Police Homicides of Civilians, 1957-1963, in Detroit's Racial Geography

This interactive map highlights 27 identified cases of police homicides of civilians in the city of Detroit between 1957 and 1963. DPD officers were responsible for 24 of these killings (22 on-duty and 2 off-duty). The other three involve a Michigan State Police Trooper operating inside the city limits, and one each from the police departments of Highland Park and Hamtramck, small municipalities located inside Detroit's boundaries. Two-thirds of the civilians whose race can be identified were African American. 70% of those shot fatally were adults, and 30% were teenagers. All but one were male. Older adults shot by police were far more likely to have been white, armed, and engaged in serious criminal activity; youth in their teenage years and early twenties killed by police were overwhelmingly African American, unarmed, and allegedly engaged in minor offenses such as burglary, reckless driving, and car theft (joy-riding). These and other key findings are detailed below the map, followed by additional documentation of featured cases.

Click on the dots to view the incident summary and source for each homicide. The darkest blue census tracts represent the most segregated African American neighborhoods, and the dark green represents the city's all-white areas, with the shifting color line in-between.

- Black circles (19) = Police homicides of adults

- Red circles (8) = Police homicides of teenagers

Key Findings:

- "Justifiable Homicide" (96%). The Wayne County Prosecutor found all on-duty officer homicides to be justified and brought misdemeanor charges only for an off-duty officer who claimed to have accidentally shot his friend in the back of the head after a night of partying.

- Unarmed and Fleeing (48%). Half of the identified fatalities (13) involved suspects who were unarmed and fleeing and posed no threat, including 7 of the 8 teenagers killed by police. Almost all of these scenarios started with traffic violations, burglary, or small-scale robbery.

- "Armed and Dangerous" (22%). Only 6 of the fatal force incidents involved situations where the suspects were armed with guns and posed clear threats to the officers or other civilians. Only two of these were armed robbery scenarios where the suspects were 'career criminals' who fired on officers. The others involved domestic disturbances, mental health emergencies, or inebriated people in bars.

- Teenagers (30%). Police officers killed teenagagers in 8 of the fatal force includents. All but one youth was unarmed and allegedly fleeing when shot from behind. See the case studies below for more information, and the "Police Shooting of Teenagers" page for two cases that generated community protests.

- Domestic Disturbances and Mental Health Crises (19%). One-fifth (5) of the incidents occurred during police responses to domestic disturbance calls or mental health crises where the officers responded to perceived threats with disproportionate force.

- Vice Squad/Sex Workers (15%). DPD officers working in "vice" districts shot and killed two alleged sex workers, including Cynthia Scott and a male-identified person "clad in women's clothing." Vice officers shot two other people during a raid on an unlicensed bar and after catching two homosexual men in a theater.

- Race (est. 60% Black). More than two-thirds (13) of the fatalities where race can be identified were African American, and one-third (6) were white. Because newspapers were more likely to identify the race of Black 'criminals,' it is likely that a significant percentage of the unidentified cases were of white males. Based on incident location and other information, our project estimates that 5 of the 8 unidentified cases involved white males. This would mean an estimated three-fifths of civilians killed by police during this period were African American.

- Gender (96% male*). All but one of the fatal force incidents involved male civilians, with the asterisk that the gender identity of one sex worker "clad in women's clothing" is uncertain.

The next three sections highlight all unarmed teenagers killed by police between 1957 and 1963, eight additional homicides of adults that were suspicious and raised questions about excessive force and even murder, and the non-fatal shooting and paralysis of an African American man during an illegal racial profiling incident.

Category 1: Seven Fatal Police Shootings of Unarmed and Fleeing Teenagers, 1957-1963

All but one of the 8 teenagers shot and killed by police officers in Detroit betweeen 1957 and 1963 were unarmed and fleeing. Four of the unarmed youth were Black males, and three were white males. Six of them were in stolen cars, a common juvenile male practice during this era known as "joyriding," although there is no evidence that police officers were aware of the auto theft in most of the shootings, which happened during chases because the teenagers were speeding and driving recklessly. Therefore it is more accurate to say that the youth were killed because they were violating traffic laws and refused to stop when so ordered. Police shot four of the teenagers after they crashed the cars and began fleeing on foot.

Paul R. Michalski (May 18, 1957). Michalski, a 16-year-old white male, was shot in the back of the head and killed by Michigan State Trooper Norman Lee during a four-mile high-speed chase in a stolen car in the city of Detroit. The officers pursued Michalski and a teenage companion after allegedly observing them driving 30 mph over the speed limit at 1:45 a.m. Both teenagers were from the suburb of Berkley. The officers stated that the youth tried to run them off the road.

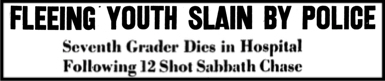

Virgil Miller (Sept. 29, 1957). Miller, a 15-year-old African American male, was shot in the head and killed during a police chase after he was driving without lights on at night. The white squad car officers, Patrolmen Robert Manzel and Sidney Oram, fired 10 shots at the youth from their moving vehicle. The truck was stolen, although the police did not know that when they killed a seventh grader for a misdemeanor traffic violation.

Peter Carr (March 15, 1958). Carr, a 17-year-old male (race unknown), was shot by Patrolman Frederick Arndt while fleeing after allegedly holding up an ice cream shop for $12.30. The teenager later died from his wounds. Carr was allegedly armed with a knife and had robbed the same shop twice before. Police said the teenager did not comply with an order to halt. It is likely that Carr was white, because of the location of his residence and because newspapers generally reported the race of Black youth implicated in crimes.

Albert Morris (April 1, 1959). Morris, a 16-year-old African American male, was shot in the back of the head by Patrolmen Robert Beasley and Harold Bouiliere after a car chase. The two white officers tried to pull Morris over for a traffic violation, but he fled, crashed the car, and then started running on foot. The officers stated that they fired after the youth ignored orders to halt. The car later turned out to be stolen. Albert Morris's mother protested the killing of her unarmed teenage son as "cold, violent, unnecessary."

Anthony Sherrard (Sept. 17, 1961). Sherrard, a 14-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by DPD Officer John Gerber after Sherrard and a friend stole a car and the police gave chase. Sherrard and a friend stopped the car and fled on foot toward the Brewster Homes project, where the boy lived. The white officer shot the 14-year-old in the back after claiming that he tried to ram them during the car chase and then ignored an order to halt while fleeing on foot. Sherrard's mother criticized the multiple officers involved for not apprehending her son without gunfire and for exaggerating his size in the incident report to make it seem as if he looked like an adult (Anthony actually was 5'4"" and 125 pounds). After Sherrard's death, the DPD publicly disclosed his juvenile record and criminalized the young teenager by stating that he had been in frequent legal trouble.

David Carson (May 13, 1962). Carson, a 14-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Peter Hall during a police chase after the boy ran a red light. Carson crashed the car, which turned out to be stolen, and began to flee on foot. Patrolman Edward Zupancic fired at Carson three times and missed. Patrolman Hall fired twice, and one bullet struck Carson in the back of the head. The police officers and newspapers reported that Carson was 5'9'' and weighed 175 pounds, and "appeared much older than 14." Carson also had escaped from a juvenile detention center, although the officers did not know that, or that the car was stolen, during the chase. The NAACP protested the killing of a juvenile, but the DPD and the prosecutor exonerated Patrolman Hall. For more information, see the detailed analysis on the Police Shooting of Teenagers page.

Kenneth Evans (July 12, 1963). Evans, an 18-year-old white male, was shot in the back while fleeing by Officers Paul Funk and Charles Archibald. Evans allegedly stole a car to joyride with friends and ran away when police tried to arrest him. The incident resulted in large protests by white and black Detroiters from his neighborhood against the DPD and sustained criticism after the prosecutor exonerated the two officers without a substantive investigation. The evidence clearly indicates that the killing of Kenneth Evans violated DPD use of force regulations. Detailed information is on the "Police Shooting of Teenagers" page.

Category 2: Eight Suspicious/Questionable Police Homicides of Adults

The Wayne County Prosecutor found all on-duty police homicides of adults and teenagers during the 1957-1963 period to be "justifiable." These seven cases involved petty theft, vice squad policing, mental health emergencies, and domestic disturbance calls in which the evidence indicates that the police action was suspicious and arguably excessive force, wrongful death, and in some cases arguably murder. It is important to note that there is very little evidence in the public record for several of these cases below and a number of other police homicides during this period, so it is often impossible to assess the veracity of the police version of events with any degree of certainty. Several of these killings also implicate police policies that permitted the use of fatal force against small-scale burglars and people undergoing mental health emergencies, as much as or more than the actions of the officers on the scene.

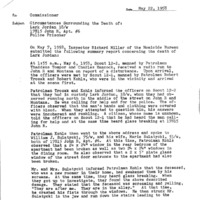

Lark Jordan (May 6, 1958). Jordan, a 38-year-old white male, suffocated in police custody. He was experiencing a mental health breakdown and calling for help when arrested for "malicious destruction of property" by two officers in the middle of the night. According to the police report, Jordan "went berserk" while being transported to Receiving Hospital, and the officers called for assistance. At least a dozen more officers arrived and as the group subdued Jordan, he died of suffocation from the straps used as restraints. The coroner ruled it "necessary to subdue the man" and found that, with the restraint straps in place, "he continued to scream, thereby exhausting most of the air from his lungs." The prosecutor found the police actions justified because of Jordan's mental illness and actions. The DPD report (at right) exonerated the officers and did not contemplate whether it was good policy, rather than legally permissible, for police to use deadly force to arrest a man for a misdemeanor property offense while he was experiencing a mental health episode.

Allen Gordon (Dec. 18, 1958). Gordon, a 44-year-old African American of unclear gender identity, was shot and killed by Patrolman Kenneth Hady of the Voice Squad after Gordon allegedly approached the undercover officer while "clad in women's clothing" and propositioned him. Patrolman Hady stated that Gordon, a presumed sex worker, fled down an alley after he showed his badge. The officer gave chase and claimed that when he caught up, Gordon pulled a knife and threatened his life. This scenario of a fleeing suspect threatening the life of an armed officer in a back alley is implausible. Hady claimed that he accidentally shot Gordon while trying to subdue him and was only trying to smash Gordon in the head with his police revolver.

Note: the photographs of the two African American males below are available because they had police records (which does not mean that they had necessarily been convicted of anything) and the DPD provided the images to the news media.

Dennis Holmes (Sept. 7, 1960). Holmes, a 26-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by DPD Patrolmen Albert Wynne and Richard Pfaff, both white officers, while hiding in a basement after he allegedly robbed a store of $20 armed with a hunting knife and fled. Officer Pfaff claimed that Holmes "moved toward him with a knife" and then, after being shot at least once, jumped up and attacked Officer Wynne, who also fired. It is implausible that a petty thief would attack two police officers holding him at gunpoint, but there were no other witnesses. Holmes died of two bullets to the chest.

Lawrence G. Paul (Dec. 29, 1960). Paul, a 21-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Donald W. Ogle, a white officer, during the crash crackdown. A woman reported that Lawrence Paul had stolen a carton of Christmas cards out of her station wagon. The officers responded and pursued the fleeing suspect, who was unarmed. According to the official report, Ogle shot and killed Paul from a distance of 200 feet. The Wayne County Prosecutor ruled the case to be a "justifiable homicide" a couple of hours later, after a cursory investigation that involved asking Ogle to make a statement. (The 1962 revision of the DPD's use of force policy disallowed firing at an unarmed and fleeing suspect for misdemeanor theft).

Otis Cotton (August 21, 1961). Cotton, a 36-year-old African American male, was shot twice and killed by white DPD officers responding to a "family trouble" call that he had threatened his wife with a knife. The policemen claimed that Cotton swung a knife at them, although he was inside his house and behind a door locked with a chain, so it is hard to imagine how their lives might have been at risk. The police were outside and shot Otis Cotton through the crack in the door.

James Howard (Jan. 18, 1962). Howard, a 41-year-old male of unknown race, was shot and killed by Patrolman Lemar Sneed of the Vice Squad after the officer tried to arrest Howard and another man inside a movie theater on a "morals offense" (meaning homosexual conduct). The officer claimed that Howard and the other man knocked his pistol out of the holster during a struggle, and that he had to shoot because Howard asked his companion to toss him a knife (At no point did Howard actually have a knife). The incident, at least as described by the officer, probably would not have been justifiable under the revised DPD policy implemented later that year since Howard was not directly posing an armed threat or fleeing to escape a felony arrest. It is likely that Howard was white, because the Michigan Chronicle did not report on the case.

Willie Ashford (Feb. 7, 1963). Ashford, a 42-year-old African American male, was shot and killed in downtown Detroit by an officer from the Highland Park Police Department (a small municipality inside the city of Detroit) while being transported to the county jail to serve 20 days for a misdemeanor drunk driving charge. Ashford broke free and was trying to climb a fence when Officer Ove Hansen shot him from behind. The NAACP, ACLU, and the National Lawyers Guild demanded prosecution since Ashford was "executed for a misdemeanor." Wayne County Prosecutor Samuel Olsen acknowledged that the shooting did not meet the legal threshold of a 'fleeing felon' but declined to prosecute, citing the officer's lack of "criminal intent" and the apparent wishes of Ashford's widow.

Cynthia Scott (July 5, 1963). Ms. Scott, a 24-year-old African American female and sex worker, was shot in the back two times and killed by Officer Theodore Spicher in the early morning hours of July 5, 1963. Spicher claimed that Scott attacked him with a knife after he sought to arrest her, allegedly for larceny. Multiple witnesses disputed this story and stated that Officer Spicher shot Cynthia Scott as she walked away after refusing to submit to an 'investigative arrest,' which he did not have the legal authority to carry out. Massive protests followed the incident and the prosecutor's exoneration of Officer Spicher. Our project has obtained the DPD Homicide Bureau file, which contains extensive evidence indicating that Cynthia Scott was murdered and that the DPD and prosecutor covered up what happened. For the full story, see the "Brutal Murder of Cynthia Scott" and "Protesting the Cynthia Scott Killing" pages.

The Shooting and Paralyzation of William C. Green

DPD officers shot and wounded a significant number of people in non-fatal incidents, almost certainly several times higher than the total homicides per year. The exact number is unknowable because the police department did not keep thorough records, the police archives are sealed, and the newspapers rarely reported non-fatal "use of firearms in police action" incidents. An exception is the case of William C. Green, who was shot and paralyzed by a white police officer during a racial profiling stop followed by an illegal "investigative arrest."

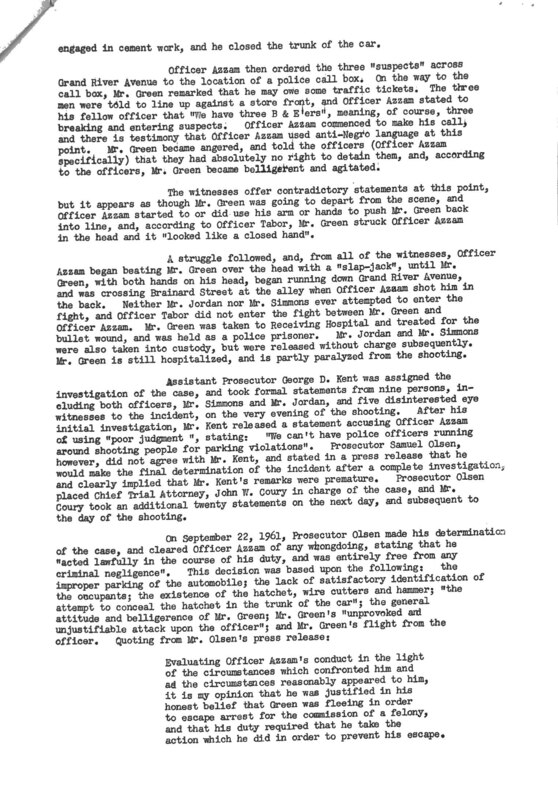

On September 18, 1961, William Green and two co-workers were parked on the corner of Commonwealth Street and Grand River Avenue to let one of the passengers get out of the car. All three were African American men. Two white officers, Patrolman Abraham Azzam and Patrolman John Tabor, stopped to investigate, allegedly because Green's car was illegally parked, too far away from the curb. William Green, a 31-year-old African American man, stepped out of the car at their request and provided his personal and vehicular papers. The officers also asked for indentification from the passangers, which one provided, but the other did not have any.

The two officers noticed a hatchet on the floor of the car under the front seat, which one of Green's passengers moved to the trunk, which already held other tools used in the men's profession: painting and masonry contract work. Officer Azzam stated to his fellow officer, "we have three B and E 'ers," referring to breaking and entering suspects. The officers led the men across Grand River Avenue to a police call box and lined them up against a storefront. Officer Azzam also used racially derogatory language toward the three men.

Defending his civil rights, William Green stated that the officers had no right to detain them and became agitated about the unfounded investigation. As Green attempted to leave, Officer Azzam pushed him back into line, resulting in a struggle between the two. Azzam began to beat Green over the head, and as Green attempted to defend himself, he also began to run away. Patrolman Azzam pursued and shot William Green in the back. Green was taken to Receiving Hospital and survived but was left partially paralyzed as a result.

William Green's saga is an example of how Detroit police officers racially profiled and commit violence against innocent African Americans. Patrolman Azzam initiated the confrontation based on an alleged traffic violation that DPD officers enforced against African Americans in discriminatory and disproportionate ways, and often as a pretext for an illegal investigative arrest and detention. Azzam escalated the confrontation after Green initially complied with his request for identification, and the officers detained the men without any reasonable suspicion, making their actions illegal, also while using racist language and brutality. Then Patrolman Azzam used lethal force against an unarmed, fleeing man, paralyzing him.

The assistant prosecutor, George Kent, conducted an investigation and publicly criticized Azzam, stating: "we can't have police officers running around shooting people for parking violations." The Wayne County Prosecutor, Samuel Olsen, then intervened and exonerated Patrolman Azzam, saying he had "acted lawfully" in every way. Olsen claimed that William Green had been "belligerent" and had made an "unprovoked and unjustifiable attack upon the officer," making him guilty of felonious assault. Prosecutor Olsen therefore ruled the shooting a "justifiable homicide," despite strong evidence that William Green had only tried to defend himself from being beaten.

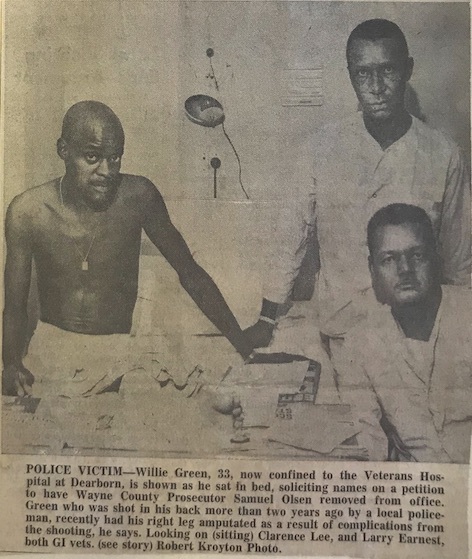

William Green eventually had his right leg amputated as a result of the shooting. He continued to press for justice and accused the Wayne County Prosecutor of a coverup, as explained by the story in the Detroit Courier (right), an African American newspaper.

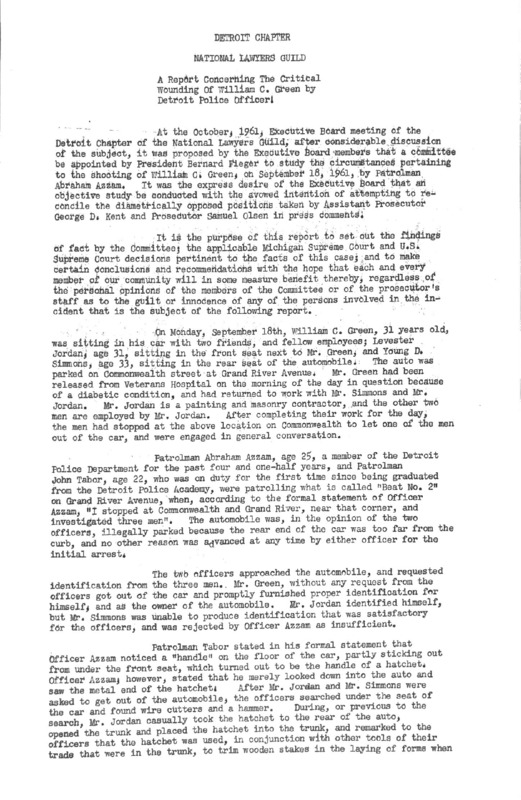

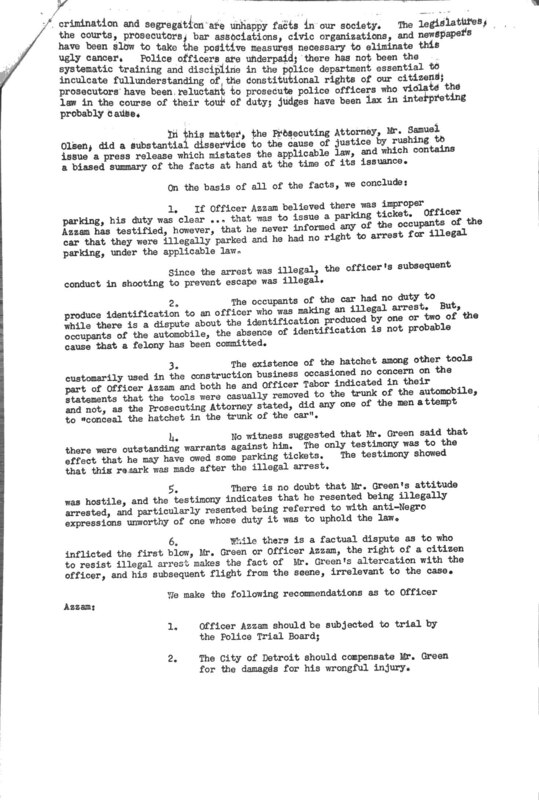

The gallery below contains an investigation of the William Green case by the Detroit chapter of the National Lawyers Guild, a left-wing organization. The report found that Azzam's actions were illegal and that Prosecutor Olsen "did a substantial disservice to the cause of justice" and reported a "biased summary of the facts" in his public exoneration.

In addition to the "Detroit Under Fire" team, Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab researchers Zev Miklethun, Maddie Turner, and Caroline Levine contributed research for this page and identified many of the homicides documented here.

Sources

Note: Sources for individual homicides are in the pop-up box for each incident in the map

Mayors of Detroit Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan/Metropolitan Detroit Branch Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Detroit News, Dec. 30, 1960, Oct. 25, 1963

Detroit Free Press, May 15, 1962

Detroit Courier, Aug. 3, 1963