Rochester Street Massacre

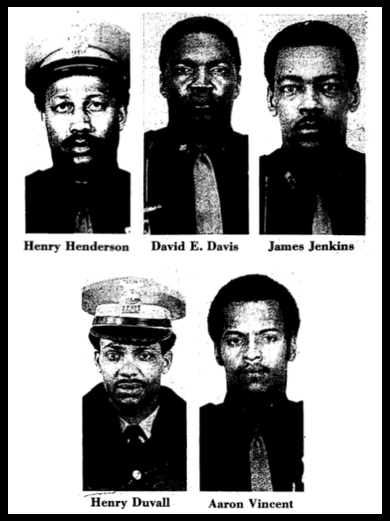

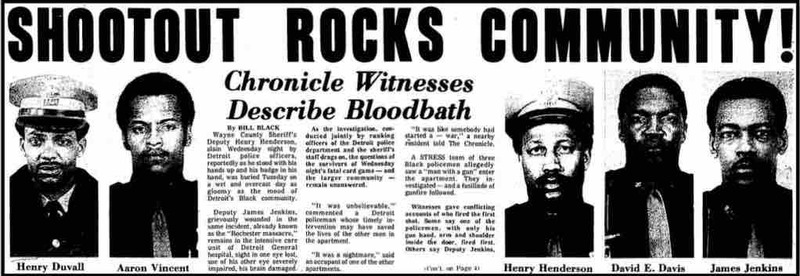

Just after midnight on March 9, 1972, three African American STRESS officers and two white DPD officers fired more than forty shots into a private apartment where six Black men had gathered for a poker game. Five of the people inside the apartment were deputies in the Wayne County Sheriff's Department, and the sixth was a civilian friend of the group. Deputy Henry Henderson died in a hail of bullets as he tried to surrender with his hands up. Deputy James Jenkins was shot and seriously wounded, also while unarmed and seeking to identify the group as law enforcement officers, leaving him permanently disabled. The others were beaten by STRESS and DPD officers after the shooting ended.

The incident, soon labeled the "Rochester Street Massacre," generated a massive outcry from the Black community (covered on the next page) and intensified demands for the abolition of STRESS. The controversy forced the DPD to scale back the deadly undercover decoy operation, which had been responsible for the vast majority of fatal shootings by STRESS units, and to implement other reforms of the program. The Wayne County Prosecutor charged the three African American STRESS officers with intent to murder while exonerating the white police officer who actually killed Deputy Henderson, leading to accusations of a coverup from a broad range of African American organizations and elected officials. The estate of Henry Henderson and the family of Deputy Jenkins eventually received a combined $2.9 million in civil litigation against the DPD and city of Detroit.

Why did a STRESS unit invade a private apartment with guns blazing, killing and wounding other law enforcement officers? The police department portrayed the encounter as a tragic case of mistaken identity, while the mainstream news media depicted the causes of the Rochester Street Massacre as a mystery. To the growing anti-STRESS movement, the Rochester Street Massacre was either the latest example of the unit's murderous shoot-first mentality, or an even more sinister illustration of the massive corruption at the heart of the Detroit Police Department, perhaps even tied to an internal law enforcement battle for control of the profits from the city's illegal narcotics markets.

What Happened at 3210 Rochester Street?

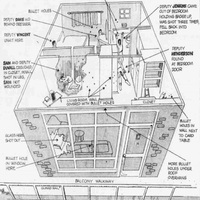

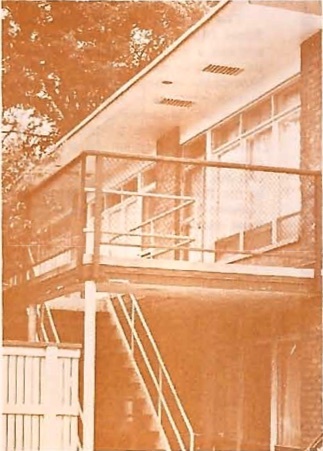

On Wednesday evening, March 8, five African American men were gathered to play poker in the second-floor apartment of Deputy Aaron Vincent of the Wayne County Sheriff's Department. Three of the other men were also deputy sheriffs--Henry Henderson, Henry Duval, David Davis--along with Richard Sain, Vincent's next-door neighbor. Most of them worked together at the Wayne County Jail. A sixth man, Deputy James Jenkins, parked his car outside and joined the group just after midnight on Thursday, March 9. All of the surviving men who were inside the apartment described a violent ambush instigated by the STRESS team, whose coverup account is recounted first.

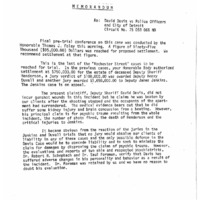

The accounts in this section of the STRESS-DPD officers who fired more than forty shots into the apartment are evaluated alongside an investigative report by the Wayne County Sheriff's Department (reproduced in full in the gallery below) that contradicted their cover story and was not released publicly. During the fallout, the DPD and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office made multiple misrepresentations of what actually happened that depended upon preventing public disclosure of the damning conclusions of this inquiry.

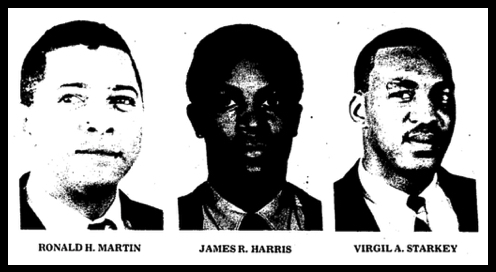

STRESS Unit #2 Able: An all-Black plainclothes STRESS team--Patrolmen Ronald Martin, James Harris, and Virgil Starkey--was near the apartment in an unmarked vehicle. According to their statements, the STRESS team "observed a lone N/M" walk from a parking lot into Apartment #14 at 3210 Rochester holding a gun in his right hand.

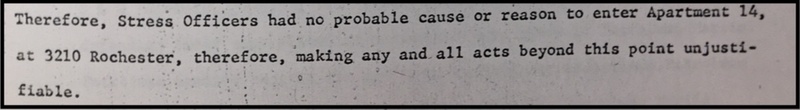

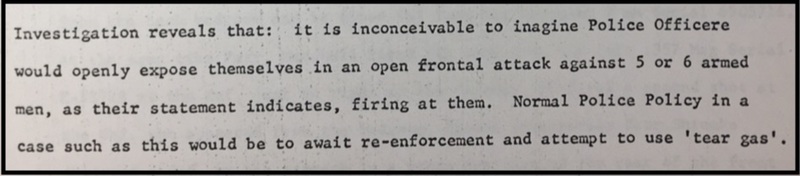

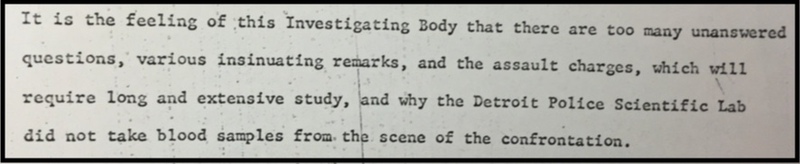

"No Probable Cause." Deputy Jenkins did have a firearm in a holster, as required by sheriff's department policy even when off duty. But the STRESS team's claim to have seen a man with a gun in his right hand enter the apartment was a lie. Investigators from the Wayne County Sheriff's Department determined that it would not have been possible for the STRESS unit to see anything more than the top of Deputy Jenkins's head from their vantage point. The investigators concluded:

STRESS Patrolmen Ronald Martin and James Harris followed the "suspect" [Deputy Jenkins] up the stairs to the apartment and entered the vestibule with their guns drawn. The patrolmen claimed that they showed their badges, identified themselves as police officers, and then the man they had been following responded by firing three shots at James Harris. [All of the men inside the apartment, whose accounts are detailed next, dispute that Jenkins fired first]. Patrolman Harris, claiming to act in self-defense, said that he then fired five shots at the gunman [all missed], and then both officers retreated for cover. The STRESS team claimed that one or more men from the apartment then ran onto the landing and fired shots at them during this retreat. Patrolman Martin claimed that he then returned fire, defending his partner.

Based on ballistics tests, the investigation by the Wayne County Sheriff's Department found that only Deputy Jenkins had discharged his handgun, among the six men gathered for the poker game, and that all of those shots had been fired inside the apartment. In effect, the STRESS team's claim to have been fired upon from the landing was another lie, contradicted by forensic evidence.

DPD Patrolmen Dennis Shiemke and David Marshall, two white officers who were not part of the STRESS unit, claimed in a statement that they were nearby in a marked scout car when they heard gunfire and responded to the scene. Patrolman Shiemke ran toward the building and joined the three STRESS officers (Ronald Martin, James Harris, Virgil Starkey) to reenter the apartment and subdue the "suspects." It is not clear how Patrolman Shiemke would have known instantly, in the dark and during the chaotic gunfire scene that he described, that the undercover STRESS team with guns drawn were police officers that he should join on their armed invasion of the apartment. Patrolman Marshall followed closely behind.

STRESS Team Lies about Taking Additional Fire. In their joint statement, the STRESS team claimed that when they reentered, the inhabitants of the apartment were firing on them from multiple locations, including the rear bedroom. All three--Patrolmen Martin, Harris, and Starkey--alleged that the "defendants" had weapons in their hands as the officers fired, reloaded, and fired some more. During this part of the encounter, the STRESS officers struck Deputy Henderson and Deputy Jenkins, who were taking cover in the rear of the apartment, multiple times. Jenkins was hit in the front of the head, the stomach and the arm. Henderson was wounded by at least three bullets.

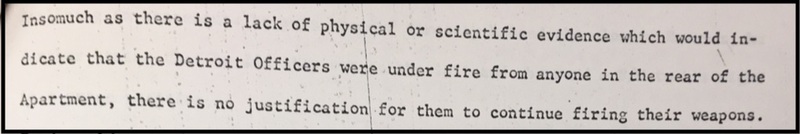

Forensic evidence and ballistics tests demonstrated that the three STRESS patrolmen lied about receiving continued gunfire after they reentered (or entered for the first time, as it is not clear that they ever retreated below the landing). According to the Wayne County Sheriff's investigation:

Fatal Shooting of Henry Henderson. Patrolman Dennis Shiemke stated that when he entered the apartment, providing support for the three STRESS officers, he saw a "defendant" in a prone position and assumed that the person had a gun even though "I could not see his hand." Patrolman Shiemke then fired a single shot from his pistol at the figure on the floor from very close range. The autopsy report revealed that this gunshot to the chest was the bullet that killed Deputy Henry Henderson, who already had been wounded by at least three other shots fired by the STRESS officers.

The DPD backup--Patrolmen Shiemke and Marshall--also claimed falsely that the apartment inhabitants were firing at them during this phase. Two other DPD officers, Patrolman Reilly and Patrolman Moultrie, arrived as backup toward the end of the incident and participated in the coverup by filing statements claiming that they had witnessed the occupants of the bedroom firing on the STRESS contingent.

Wounding of Deputy Jenkins and Deputy Duvall. The five DPD officers who invaded the apartment fired at least 44 shots, including multiple bullets that disabled James Jenkins and one that struck Henry Duvall. Most of the gunfire came from the three STRESS officers, who claimed to be acting in self-defense. The investigation by the Wayne County Sheriff's Department found "no physical or scientific evidence which would indicate that the Detroit Officers were being fired upon" after they reentered the apartment with backup. Patrolman Shiemke fired only one shot, the fatal bullet that entered Henry Henderson. Patrolman Marshall followed his partner into the apartment and fired at least two shots in the chaos that followed.

The STRESS officers claimed that they stopped firing after hearing one of the men in the bedroom yell, "I am a policeman too" and "I am a Wayne County Sheriff." The inhabitants of the apartment disputed this claim and insisted that they had repeatedly identified themselves as law enforcement officers, to no avail. Additionally, two civilian witnesses who were in an adjacent apartment in the building, Barbara Able and Sharon Addison, gave statements confirming that the shooting continued even after the inhabitants identified themselves as sheriff's deputies. The apartment inhabitants, as discussed below, also charged that the DPD officers beat and assaulted them after they had surrendered.

Although the STRESS officers lied about almost every aspect of the encounter, the Wayne County Sheriff's Department investigation concluded that it was "impossible" based on the forensic evidence to determine who fired the first shots, Deputy Jenkins or STRESS Patrolmen James Harris and Ronald Martin. The answer to that mystery, therefore, depends heavily on the accounts of the surviving witnesses who were inside the apartment when the STRESS team ambushed it, covered next.

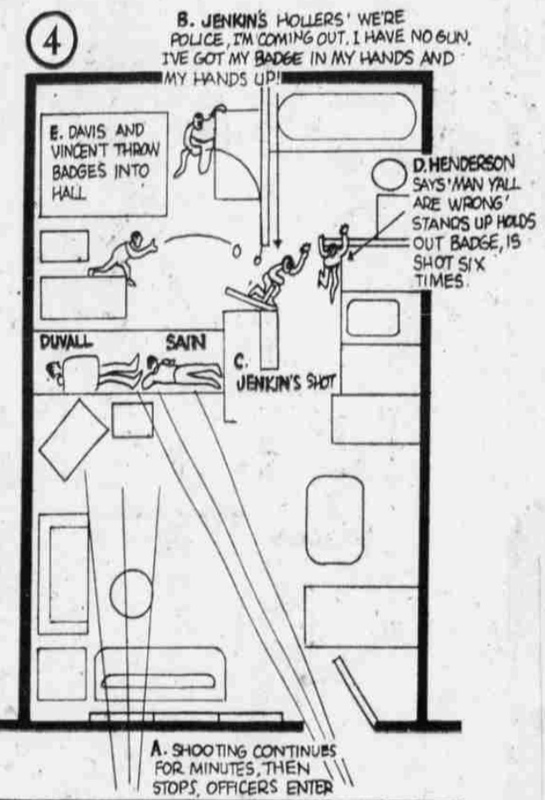

The gallery below includes the full investigative report by the Wayne County Sheriff's Department, two excerpts from a very distorted report on the Rochester incident by DPD Commissioner John Nichols, and a newspaper depiction of the scene based on the testiony of the surviving sheriff's deputies.

What Really Happened? The Victim Perspectives

The sheriff's deputies and civilian who survived the Rochester incident described a deadly ambush by the STRESS team and DPD contingent, followed by police beatings of the survivors, even after they had clearly identified themselves as law enforcement officers. All of the inhabitants of the apartment disputed the STRESS version that Deputy Jenkins fired first. All of them also stated that Deputy Henderson was holding his badge in the air to identify himself as a law enforcement officer when he was shot and killed, and that Deputy Jenkins was doing the same when shot and wounded during the second round of gunfire. The forensic evidence overwhelmingly supports their account.

The main point of tension in the accounts of the inhabitants inside the apartment is whether Deputy Jenkins pulled his gun before or after being shot at during the first exchange with the STRESS teams. All of them agreed that the armed man outside the door [STRESS Patrolman Harris] initiated the encounter and shot first. All of them also insisted that no one except DPD officers fired their weapons after the initial exchange, which the forensic evidence confirmed.

The three sheriff's deputies and one civilian who gave statements to the police investigation and to the media all took refuge in the back bedroom for most of the encounter. The body of Deputy Henry Henderson was found at the door to the bedroom, and Deputy James Jenkins was critically wounded as he tried to stop the attack by leaving the bedroom while holding up his badge.

- Deputy Henry Duvall, a 29-year-old African American male, said that Deputy Jenkins shouted "we're police officers in here!" when the man with a gun first appeared outside the door. The armed man then fired several shots at Jenkins, who returned fire. Deputy Duvall ran and hid in the bedroom with several others. He called out that he was a law enforcement officer, and someone yelled, "How do we know that?" and so he threw his badge out into the main room. Then Duvall saw Deputy Jenkins walk into the living room with his badge and hands in the air, only to be shot down in a hail of bullets. He also saw Deputy Henderson shot while "in a position of surrender" and continue to be shot while lying on the ground. After the gunfire subsided, the DPD officers kicked and beat Duvall, who ended up in the hospital with a bullet wound in the leg.

- Deputy Aaron Vincent, a 23-year-old African American male and host of the poker game, said that he was talking on the phone with his fiance (Gwendolyn Kreger) when someone at the door yelled "Police Officer" and immediately began shooting. Deputy Jenkins had just arrived and was taking off his coat when this man [presumably STRESS Patrolman Harris] shot him through the open doorway. Vincent hid in the back bedroom with several others as the gunfire continued, but Deputy Henderson did not make it and fell to the ground, wounded, beside the bedroom door. Vincent and several others threw their badges into the living room while yelling that they were law enforcement officers too. Then Deputy Jenkins walked into the living room holding his badge in the air, with his hands up, and the STRESS officers started shooting at him. When it was over, DPD officers handcuffed Aaron Vincent and then kicked and punched him, and also smashed him in the head with the butt of a shotgun, for which he received medical treatment at the hospital.

- Richard Sain, a 32-year-old African American male and the next-door neighbor, corroborated Vincent's account in a statement released jointly through the same attorney. Sain said he was playing cards when the first STRESS officer opened fire, and he then hid in the bedroom closet during the shooting. Sain heard the deputies yell out that they were with the Sheriff's Department, but the shooting continued. After it was over, Sain accused DPD officers of kicking him in the head and stomping on him.

- Deputy David Davis, an African American male [age unclear], said that Deputy Jenkins entered the room where the group was playing cards and was removing his coat when a voice from outside yelled, "Come on out of there, mother fucker." He saw Jenkins reach for his gun and start to turn around when a burst of gunfire came through the door. Davis began to draw his own gun but thought better of it and hid in the back bedroom with Deputy Vincent and others. After the gunfire stopped, several DPD officers kicked and pistol whipped him.

- Two additional witnesses, Gwendolyn Kreger (Deputy Vincent's fiance, who was on the phone) and Sharon Addison (Vincent's neighbor), confirmed Davis's account that someone yelled "Come on out of there mother fucker," and then started shooting.

"It was murder." Two of the sheriff's deputies gave even stronger statements, anonymously, to the Michigan Chronicle. One (later identified as Henry Duvall) charged that "it was murder," because the DPD officers shot Henderson and Jenkins as they had their hands in the air, trying to surrender. Another asked why the STRESS team had not followed proper procedure and wondered if the attack had been deliberate: "If they were investigating, then why didn't they seal off the apartment, call for reinforcements and flush us out?"

Deputy James Jenkins, who underwent emergency surgery and was hospitalized with brain damage and lost eyesight, among other injuries, could not give a statement to the investigators. He did support their accounts in later testimony at trial and insisted that he was unarmed and trying to surrender when shot in the second wave of the attack.

Patrolman Richard Herrold, a DPD officer who responded to the scene, told the news media that he stopped a white police officer from executing two of the sheriff's deputies after they had surrendered and were in custody. Herrold, who also testified at trial, said that a white policeman held a gun to Deputy Henry Duvall's head and said "I don't give a damn" when Herrold informed him that Duvall was a law enforcement officer. Patrolman Herrold also stated that he witnessed DPD officers beating Deputy Aaron Vincent while he was handcuffed, that DPD officers waited ten minutes to remove the dying Henry Henderson on a stretcher, and that the five shooters (the STRESS team and the DPD backup) huddled in a corner of the apartment to get their stories straight. (Note: Patrolman Herrold was indicted a year later for cocaine and heroin trafficking, and his willingness to buck the "Blue Curtain" and testify against the STRESS officers fueled the speculation that the Rochester Incident was linked to a "turf war" between law enforcement factions over payoffs from street-level dealers).

Selective Charges and Accusations of a Coverup by the DPD and Wayne County Prosecutor

Immediately after the Rochester Incident, DPD Commissioner John Nichols and Wayne County Sheriff William Lucas released a joint statement labeling the event a "terrible tragedy" and a "complete misunderstanding"--a transparent and clearly premature attempt to sideline questions of criminal conduct by the STRESS team and their DPD backup. During the weeks that followed, Commissioner Nichols continued to cover for the STRESS team, even after incontrovertible evidence emerged that the three patrolmen (and multiple other DPD officers) had lied about everything that happened that could be evaluated through physical evidence, and even after the eyewitness testimony of all of the surviving deputy sheriffs disputed their claims of firing only in self-defense. In a March 28 report to the Detroit city council (reproduced in gallery above), Nichols presented the dishonest statements of the STRESS team and its DPD backup as the factual description of the encounter and cast doubt on all of the competing accounts by the sheriff's deputies and their friends and acquaintances.

This preemptive attempt to cover up what really happened did not last, because the surviving witnesses told their stories to the news media and not just to the homicide investigators, and because the escalation of anti-STRESS protests made it impossible to keep a lid on the "Rochester Street Massacre." Since the victims in the attack were law enforcement officers--and probably also since the primary targets of the criminal inquiry were Black policemen--the homicide investigation was much more thorough than the typical predetermined outcome of processes designed to exonerate police officers who shot and killed Black civilians. In particular, the investigative report by the Wayne County Sheriff's Department definitively disproved the accounts of self-defense concocted by the STRESS team and backup DPD contingent, as detailed above, and concluded with the assessment that it was "inconceivable to imagine" that police officers would launch an "open frontal attack" on the apartment if the men inside had really been an armed criminal threat (excerpt at right).

Additional Evidence of a DPD Coverup Conspiracy: The Wayne County Sheriff's Department investigation, which was sent to the prosecutor but not made public, contained extensive evidence indicating that the STRESS and DPD officers on the scene covered up what happened and that the follow-up inquiry by the DPD Homicide Bureau was not impartial. In addition to the findings that the STRESS unit comprehensively lied about the circumstances of the incident, the sheriff's department report emphasized five additional developments that raise further questions about what happened that night, why it happened, and whether the Rochester Street Massacre was a deliberate and organized conspiracy by the STRESS team and probably other DPD officers as well. There is little question that whatever the motive for the attack, the aftermath produced a corrupt and widespread DPD conspiracy to suppress the truth of what happened.

- First, STRESS Unit #2 Able did not notify the precinct dispatcher about their decision to enter the apartment to apprehend a suspect with a gun (Deputy Jenkins, which forensic evidence revealed to be a fabrication), even though they had previously called in other incidents that night.

- Second, a white decoy STRESS officer dressed like a hippie assaulted Gwendolyn Kreger, the fiance of Deputy Aaron Vincent, who was on the phone with him when the shooting began and who rushed to his apartment in distress. It is not clear why a second undercover STRESS team would have been immediately on the scene, within minutes, if the all-Black STRESS Unit #2 Able had really just happened to stumble upon Deputy Jenkins on his way into the apartment.

- Third, the DPD scout car transporting two badly wounded deputies (Henry Henderson, who later died, and Henry Duvall) drove them past Henry Ford Hospital, which was nearby, to Detroit General Hospital, which was twice as far away. The two DPD officers then fabricated an explanation that Henry Ford was closed even though a team of doctors was standing by and ready to operate after hearing about the casualties over police radio. The apparent desire to delay medical care for the deputies raises questions about what the DPD officers on the scene were trying to hide. (They also delayed removing Henderson from the apartment on a stretcher for at least ten minutes after the shooting ended).

- Fourth, there was evidence that DPD officers and agencies ignored or altered evidence from the scene. Among other suspicious developments, DPD investigators did not gather all of the spent bullet casings and enter them into evidence; the Detroit Police Scientific Lab did not take blood samples from victims, a protocol violation; and the DPD Homicide Bureau pressured the Medical Examiner to alter the autopsy report of Henry Henderson to make it seem that the fatal bullet was fired from farther away.

- Fifth, the DPD Homicide Bureau investigation sought to confuse the sheriff's deputies and civilian witnesses by sending more than 100 police officers through each line-up, far in excess of standard procedures, and presumably so that they would not be able to identify the actual shooters and the men who beat them in the aftermath. The DPD then discredited the witnesses, including the county law enforcement officials, when they proved unable to definitively identify the roles played by the individual officers involved.

Suppressing the Sheriff's Department Investigation. The internal investigation by the sheriff's department, which concluded that "too many unanswered questions" remained about the causes and coverup of the Rochester Incident, placed significant internal pressure on the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor to take at least some action. This accompanied heightened scrutiny for Sheriff William Lucas, who was African American and closely allied with DPD Commissioner John Nichols and Mayor Roman Gribbs. Despite the findings of his own agency's (non-public) investigation, Lucas continued to maintain publicly that the Rochester Incident was primarily just a misunderstanding, and he seemed most concerned not with the lives of his deputies but with the likelihood that the community backlash against the Rochester Street Massacre would force the DPD to end the STRESS decoy program, which he considered an invaluable crime-fighting resource (gallery below left). The union for Wayne County Sheriff's Deputies even accused William Lucas of participating in a coverup and warned of a "whitewash for political expediency."

Selective and Compromised Prosecution: On March 24, Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan announced that the three African American STRESS officers--Ronald Martin, James Harris, and Virgil Starkey--would be charged with assault with intent to kill Deputy James Jenkins based on their "overreaction" at the scene. Despite the findings of the sheriff's department investigation, Cahalan accepted the STRESS team's claim to have seen Jenkins walking to the apartment with a gun in his hand, which significantly weakened his own case and raises questions about whether the prosecutor actually wanted to convict the STRESS officers or was primarily responding to the massive public pressure for at least some charges. Cahalan also accepted the STRESS team's claim that Deputy Henry Henderson was wielding a gun when they shot him in the second wave of the attack and did not charge them for assault with intent to kill the man who actually died. This was a highly questionable and indeed suspicious determination, because all of the surviving victims testified that Henderson was unarmed and trying to surrender, and because it had the foreseeable impact of undermining the prosecution's own case against the STRESS team by giving them a self-defense justification.

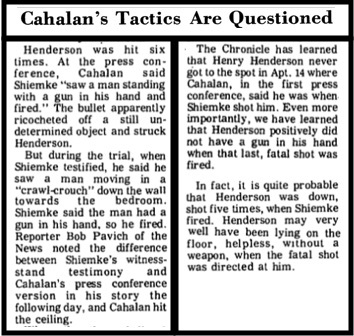

Cahalan simultaneously exonerated Dennis Shiemke, the white DPD officer who fired the fatal shot that killed Deputy Henry Henderson while he was wounded and prone on the floor. The prosecutor based this decision on the STRESS team's assertion that Deputy Henderson was holding a gun in his hand, even though they had lied about everything else and Patrolman Shiemke had acknowledged that he did not see a gun in his initial statement to investigators. The prosecutor concluded that Patrolman Shiemke and his partner were responding to the STRESS team's report of shots fired by the suspects and "acted to protect the lives of his brother officers and himself." Patrolman Shiemke's actions were therefore a "justifiable homicide" carried out "in the line of duty." In making this controversial determination, Prosecutor Cahalan did not address the obvious problem that Patrolman Shiemke and his parter, Patrolman David Marshall, had falsified their incident report in order to support the STRESS team's claims that the inhabitants of the apartment were firing on them from the rear bedroom. (Since incident reports were not public, media coverage did not recognize this deliberate oversight on the part of the prosecutor).

Despite all this, Sheriff William Lucas closed ranks and expressed his satisfaction that the prosecutor's inquiry had been fair and thorough. After the announcement, Deputy Henry Duvall publicly denounced Prosecutor Cahalan as a "liar" for participating in the coverup that Deputy Henderson had a gun in his hand when he was shot multiple times, insisting that "they murdered him and anybody who says different is lying."

Accusations of a Prosecutorial Whitewash: The Wayne County Prosecutor's failure to indict the white police officer (or the African American STRESS officers) for the shooting and killing of Deputy Henry Henderson drew a massive outcry of racism and selective enforcement from across the African American community. So did the refusal to indict any DPD officers for wounding Deputy Duvall and for beating the survivors after they surrendered, which Cahalan rationalized based on their inability to identify their attackers in the suspect lineup, without acknowledging that the DPD deliberately and irregularly designed the process to make such identification impossible.

The Labor Defense Coalition and the Guardians of Michigan (the association of Black police officers) reiterated their demands for the abolition of STRESS and requested that the Wayne County Grand Jury initiate an independent inquiry into the fatal shooting of Deputy Henderson and the non-fatal shooting of Deputy Henry Duvall. The grand jury agreed to launch this investigation but then retreated amid allegations of "undue influence" from the prosecutor's office. Among other improper activities, Prosecutor Cahalan threatened to hold grand jurors in contempt, and assistant prosecutors called them at home to intimidate them. The Michigan Chronicle reported on the widespread sentiment among Black residents of Detroit that the police department and the prosecutor were whitewashing the full story, with many comparing the situation to the law enforcement coverup of the Chicago Police Department's murder of Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in 1969. Newspaper reports that the Detroit Police Officers Association union had threatened a mass walkout by white officers if the homicide investigation resulted in charges for Patrolman Shiemke also fanned the accusations of a racist coverup by the DPD and Prosecutor Cahalan. An anonymous "concerned citizen" wrote a letter to Sheriff Lucas (gallery below) in anger at the lack of justice for Henry Henderson, charging that "if that had been a black police kill a white police it would have been murder in the first degree."

STRESS Officers: "Not Guilty." All three STRESS officers were aquitted by a jury evenly divided between white and Black members in the assault trial that took place that summer. The STRESS team testified that Deputy Jenkins had fired first at Patrolman James Harris and that Deputy Henderson was holding a gun in a threatening position when they shot him down. Other DPD officers testified that Deputy Henry Duvall had initially told them that Deputy Jenkins fired first, which Duvall denied and attributed to an apparent DPD conspiracy to protect the STRESS officers. In a dramatic moment, Deputy James Jenkins, who was disabled from the three bullet wounds he suffered, appeared in court and directly repudiated the STRESS team's story, insisting that he had been unarmed, holding his badge, and trying to surrender when shot. Jenkins also testified that he was not carrying a gun in his hand when he entered the apartment. The defense team responded by casting doubt on his memory because of the brain damage.

After the not guilty verdicts, a number of critics charged that the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office had undermined its own case in a strategy to evade a full accounting of what had transpired. Prosecutor William Cahalan further encouraged this interpretation by not appearing to be disappointed at the outcome and praising the defense team and the jury for their contributions to a fair verdict. In particular, Cahalan received another round of intense criticism for not indicting Patrolman Dennis Shiemke for the killing of Henry Henderson, because Shiemke testified at the trial that he had feared for his life but had not actually seen Henderson holding a gun, despite Cahalan's public insistence that Shiemke had. In a retrospective analysis (right), the Michigan Chronicle pointed out the multiple inconsistencies in Shiemke's shifting testimony and Cahalan's misrepresentations of the physical evidence surrounding Henry Henderson's death, concluding that "we may not ever know the truth about what occurred."

The gallery below contains Sheriff William Lucas's widely criticized position on the Rochester Incident; condemnation of the Sheriff's Department, DPD, and Prosecutor's Office for not seeking first-degree murder charges for the death of Henry Henderson; and a report by two Wayne County Circuit Judges accusing Prosecutor William Cahalan of misconduct, "numerous misstatements of law," and improper intimidation of the grand jury in his attempt to prevent an independent inquiry into the actions of the STRESS and DPD officers.

Sheriff William Lucas's retrospective on Rochester Incident, defending STRESS, in National Police Journal (Summer 1972) [3 pgs.]

Guardians of Michigan demand first-degree murder charges for the "Assassination STRESS Squad" (3-9-72)

Postscript: A Lingering Mystery, and the Divergent Paths of Black Law Enforcement Officers

In 1973, the radical group From the Ground Up investigated the Rochester Street Massacre in its expose "Detroit Under STRESS" (right). The organization labeled the incident the key turning point in the history of the STRESS operation, because a complete "whitewash of police murder" was not possible when the victims were other law enforcement officers, and so "there was a selective prosecution." From the Ground Up accused the DPD and the Wayne County Prosecutor of participating in a conspiracy to prevent the full disclosure of what happened during the Rochester Incident, and even more so why it happened, a story that would probably never be told. But the radical organization proposed one explanation based on sentiment circulating in the neighborhood where the STRESS ambush of the sheriff's deputies took place: "There were constant rumors that it was really a 'battle for turf' by different law enforcement agents competing in the building of the local heroin trade," especially "regarding which heroin dealer worked for which officer." Whether this was the "real story" is unknowable, but the pervasive corruption within the Detroit Police Department, including the deep complicity of dozens if not hundreds of officers in the narcotics trade, makes this possibility more than just idle speculation.

The other possibility for why the Rochester Street Massacre happened is more prosaic: an undercover STRESS team assumed that a Black male on the streets of Detroit [James Jenkins] was a criminal and went in shooting. Then, when the DPD officers encountered resistance, they fired back with overwhelming and disproportionate force and beat the survivors. This scenario fits with the racial profiling and shoot-first philosophy of the ultraviolent STRESS operation, although it was unusual that in this case the undercover unit and not just the victims were African American. Then, as usual, the DPD and the Prosecutor's Office did their best to whitewash the investigation and blame the victims.

STRESS Patrolman Ronald Martin. After the "not guilty" verdict, the Detroit Police Department welcomed back the three African American STRESS officers--Ronald Martin, James Harris, and Virgil Starkey--prosecuted for assault with intent to kill Deputy James Jenkins. Less than a year later, in the spring of 1973, DPD Commissioner John Nichols even took Patrolman Martin to Washington, D.C., to represent the STRESS operation in an adversarial hearing conducted by Detroit Rep. John Conyers for the Select Committee on Crime in the U.S. House of Representatives. Martin praised the STRESS unit as an efficient crime-fighting operation and then retold his version of the Rochester Street Incident under hostile questioning from Rep. Conyers (gallery below left). Commissioner Nichols then praised Patrolman Martin, who participated in the fatal shooting of Deputy Henderson and the permanent disabling of Deputy Jenkins, and clearly falsified his report of the incident, as a model STRESS officer and one of the unit's many "fine young examples of good, honest policemen."

Deputy James Jenkins filed a civil lawsuit against the Detroit Police Department and the officers who shot him, asking for $4 million in damages for his brain injuries, blindness in one eye, and other disabilities. In 1978, seven years after the Rochester Incident, the case went to a trial by jury, which awarded Jenkins $1.5 million and his wife Joann an additional $150,000 for their pain and suffering. The city of Detroit refused to pay, pending an appeal, but ultimately settled with the Jenkins family for $2.15 million in late 1979.

Paulette Henderson, the widow of Deputy Henry Henderson and mother of their two children, filed a wrongful death lawsuit for $5 million against the Detroit Police Department almost immediately after the Rochester Incident. In 1978, after losing by jury trial in the Jenkins lawsuit, the city of Detroit negotiated a settlement and paid Mrs. Henderson a total of $750,000, without admitting wrongdoing on the part of its officers.

Deputy Henry Duvall, who accused the STRESS team of murder and publicly labeled Prosecutor William Cahalan a liar, filed a civil lawsuit against the five DPD officers who discharged their weapons in the Rochester Incident and against the city of Detroit. In 1979, a jury found the DPD liable and awarded Duvall $100,000 for the gunshot wound in his leg and for "permanent continuing psychic trauma."

Deputy David Davis sued the five DPD officers and the city of Detroit and received a $95,000 settlement for "psychic trauma" from the death of his friend Henry Henderson, the disability of his friend James Jenkins, and the beating that he received after surrendering. The Law Department's recommendation to settle the lawsuit acknowledged the medical evidence that Davis had suffered a concussion and a kidney injury that night.

Proceed to the next page for the community protests and reforms of STRESS that followed the Rochester Street Massacre.

Sources:

Jim Neubacher and John Griffith, "All Shots Were by STRESS, 3 Say of Deputy's Slaying," Detroit Free Press, March 10, 1972

Jim Neubacher, "Survivors Tell of Shoot-Out by Deputies and Police," Detroit Free Press, March 12, 1972

Bill Black, "Shootout Rocks Community! Chronicle Witnesses Describe Bloodbath," Michigan Chronicle, March 18, 1972

John Griffith, "Assault Charges to 3 STRESS Men in Shooting of Deputies during Raid," Detroit Free Press, March 25, 1972

Bill Black, "Rochester Incident Settled--Or Is It?" Michigan Chronicle, Aug. 19, 1972

Additional information on the Rochester Incident and trial drawn from Detroit Free Press, March 12, 15, July 7, 28, August 2-3, 1972; Michigan Chronicle, March 25-26, April 1, 8, 29, July 22, 1972

Civil litigation information in Detroit Free Press, Feb. 2, 1978, Nov. 8, 1979; Michigan Chronicle, Feb. 4, 1978

William Lucas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

From the Ground Up, "Detroit Under STRESS," 1973, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

“Street Crime in America: The Police Response,” April 12, 1973, Hearings before the Select Committee on Crime, House of Representatives (Washington: GPO, 1973)

Maryann Mahaffey Collection, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library