Discretionary Policing

As black and white Detroiters became concerned about growing rates of poverty and crime in their city, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and members of City Council passed a series of "get-tough" ordinances in 1964 and 1965 that expanded and formalized police officers’ discretionary authority on the streets. After a department order in 1963 stopped officers from making illegal investigative arrests, police officers claimed that they hesitated to enforce the law because they feared being sued for making false arrests. To restore officers’ confidence and deter crime, Police Commissioner Ray Girardin requested that the City create these ordinances, including two prohibiting carrying knives and loitering. They were tools of “discretionary policing,” or laws whose enforcement was based on individual officers’ judgment. Many middle-class moderate African Americans supported the white liberal politicians and their goal to reduce crime. However, radical African American groups questioned whether these new ordinances were truly intended to curb crime or to update older, illegal tactics, giving police officers the freedom to arrest civilians at will.

The Detroit Free Press reported that investigative arrests composed nearly half of the 60,000 arrests made by the Detroit Police Department in 1958. As the result of pressure from civil rights groups and several Supreme Court rulings issued in the early 1960s, Commissioner Girardin ordered that officers discontinue this illegal tactic in 1963. Police officers argued that this order and the Supreme Court decisions made them hesitate to arrest suspected criminals and limited their ability to keep the streets of Detroit safe.

In the Detroit Free Press article with the headline pictured to the right, an officer explained the changes he saw after these decisions:

“There was a time . . . when a scout car crew could shake down four or five guys standing on a street corner and maybe come up with at least one gun. The guy carrying the gun would be arrested for carrying a concealed weapon and after some talking he would confess to a dozen or so holdups. Now the scout car crews refuse to even talk to these guys."

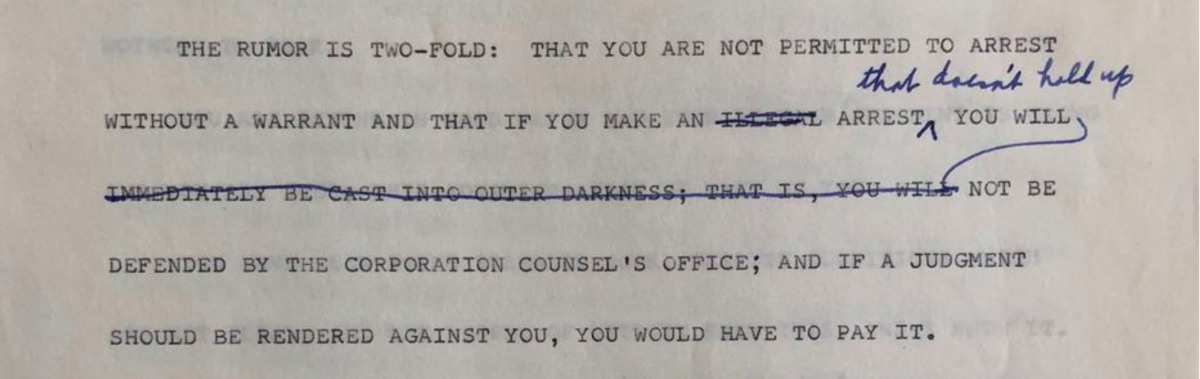

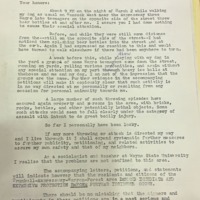

Commissioner Girardin tried to restore his officers’ confidence through a speech on February 9, 1965. He denied rumors that the Detroit Police Department would not support officers who made arrests without warrants. Notice (above) how Girardin or an aide crossed out “an illegal arrest” and replaced it with “an arrest that doesn’t hold up.” The department did not want to admit that the tactics it had been using for years violated the law, preferring to gloss over them with euphemisms such as this one. In the same way that Girardin replaced a harsh phrase with a softer one that had a similar meaning, the city replaced the illegal policy of investigative arrests with new ordinances that allowed police to exercise the same powers.

The Anti-Knife Ordinance

After a series of stabbings in the summer of 1963, Detroit’s City Council passed an anti-knife ordinance that prohibited anyone younger than twenty-one from carrying knives in public. When a high school basketball game on March 9, 1965, ended in the stabbing of nine white boys and one black girl, Mayor Cavanagh and a committee of city officials proposed a state law to turn the misdemeanor into a felony, “thus empowering police to search a suspect ‘on reasonable belief.’”

Because this effort to pass a state law failed, the City Council considered a new, stronger version of the city ordinance that would permit police to arrest knife-carriers of any age and detain them overnight. In the Detroit Free Press, Democratic councilmen Edward Connor and Mel Ravitz questioned the constitutionality of the ordinance because it would lead to “wholesale arrests and searches” of anyone who could reasonably be suspected of carrying a knife.

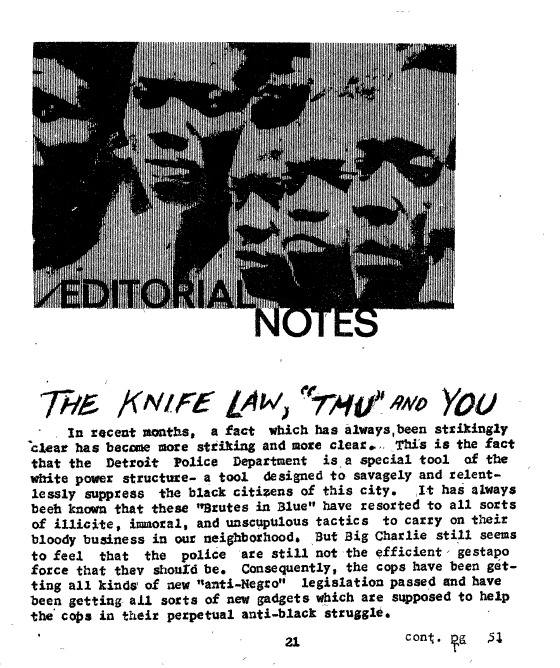

Like Detroit’s liberal politicians, moderate African American civil rights organizations and radical black groups were divided on the ordinance. The Detroit Urban League supported the ordinance because its members feared the increase in violent knife-crimes perpetrated by young people. The Michigan Chronicle reported that the DUL asked Cavanagh to “call together a broad and representative group of citizens in an effort to develop new guidelines and new approaches in an all-out massive program to help abate this typical and anti-social behavior.” In contrast, the League of Black Workers, a radical labor organization, described the anti-knife ordinance as “anti-Negro legislation” that had been “designed to provide a way to pack up Negroes, beat and torture them, and then convict them, of carrying a knife when the cops can’t stick any other charges.”

Although the anti-knife ordinance divided white liberal politicians and black organizations across the political spectrum, the Detroit City Council passed it in May 1965. Which group correctly predicted the actual effects of the ordinance? Did it discourage young people from using knives to commit crimes? Did police officers use the knife ban as an excuse to stop young African Americans on the streets? Statistics about the enforcement of the ordinance are absent from the archives. Even if data did exist, it could not capture the nature of each individual interaction between officers and the citizens they charged with knife-carrying.

The Anti-Loitering Ordinance

“It shall be unlawful for any person to loiter on any street, sidewalk, overpass or public place . . . so as to hinder or impede or tend to hinder or impede the passage of pedestrians or vehicles.” City of Detroit Ordinance Section 58-1-10

In February 1964, Police Commissioner Girardin proposed a stricter version of the city’s anti-loitering ordinance to give officers the authority to pick up people they suspected of crimes such as prostitution and mugging without risking a false arrest lawsuit. Girardin explained to the Detroit Free Press that the ordinance “would give the man on the beat needed backing in carrying out the arrests he now has to make illegally,” and Police Superintendent Eugene Reuter “said that the department sometimes makes up to 800 such [illegal] arrests a month and that many more could be made under the proposed ordinance.” The city passed the loitering ban, legalizing arrests that were once illegal.

A Total Action Against Poverty (TAP) study found that impoverished areas of the city, where the majority of African Americans lived, had the fewest outdoor recreational areas. Without access to parks and other designated spaces to gather and socialize, many people who were mostly young and African American had no other place to gather than on the streets of their neighborhoods.

Often, middle-class homeowning residents who belonged to block clubs complained about young “hoodlums” gathering in their neighborhoods and causing trouble. A block club in the second precinct sent a signed petition to Mayor Cavanagh, Commissioner Girardin, and Councilman Mel Ravitz “demand[ing] immediate and extensive protection.” Residents of the mostly white neighborhood described living in “a state of siege” because “groups of late teenagers (and early 20’s) loiter frequently in the corner areas. . . . It would seem particularly important to break up this group, gang-type, loitering, menacing, and attacking.”

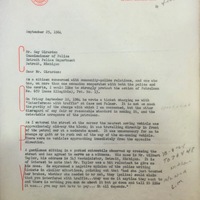

Although the police did issue tickets to some people engaging in criminal activity, many argued that the anti-loitering law allowed prejudiced officers to abuse their authority. An African American man named James Boyce wrote this letter to Commissioner Ray Girardin to protest the actions of an officer in plainclothes who gave him a ticket for loitering in September 1964. Boyce had crossed the street with ample time to reach the other side before oncoming traffic arrived. An unidentified officer with his hand near his pistol approached and asked to see his identification. To Boyce, it seemed “fairly obvious that the charge of interference with traffic was incidental to the primary purpose of carefully scrutinizing the details of [his] driver’s license.” He wrote to Girardin because he believed he and other members of his community should not have to feel “harassed and intimidated by policemen who abuse the privileges and authority entrusted to them.”

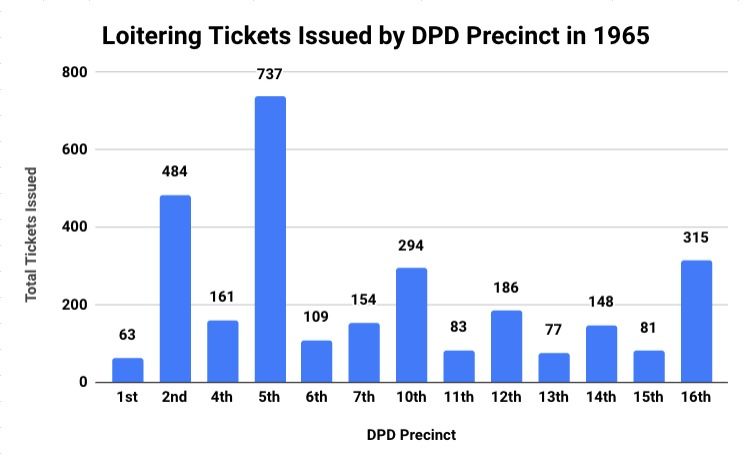

Map of Loitering Tickets by DPD Precinct, 1965

Leaders of radical civil rights organizations such as the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME) argued that police disproportionally issued tickets for loitering in impoverished, majority African-American neighborhoods and that they used loitering tickets to target the members of groups such as ACME for their political activism. A DPD report about the number of loitering tickets issued in 1965 in each police precinct confirms this interpretation, as visualized on the above map. The DPD issued 2,892 tickets to pedestrians for loitering in 1965. In the mostly white 1st precinct, officers issued only 63 tickets, while in the mostly African American 5th precinct, officers issued 737 tickets, 427 to juveniles. Explore the above map to see how the policing of loitering in the city differed based on racial demographics.

Moses Wedlow, a civil rights activist with the Adult Community Movement for Equality, challenged the loitering ordinance as unconstitutional after he received a ticket in June 1965. The Detroit branch of the ACLU represented Wedlow in the appeal of his conviction. The ACLU argued that the loitering ordinance was unconstitutional because it was overly broad and because it served as a pretext for police officers to conduct illegal searches. In 1969, the Michigan Court of Appeals rejected Wedlow's claims based on the police officer's testimony that he was impeding pedestrians on the sidewalk, a decision that reflected willful judicial blindness to the actual purposes of the anti-loitering law, to criminalize African Americans in Detroit and allow the police to search and detain them anytime and anywhere in public.

The 5th precinct, where officers issued the highest number of loitering tickets in 1965, was the site of the 1966 “Kercheval mini-riot.” On August 9th, officers in a Big Four cruiser confronted members of the Afro-American Youth Movement (AAYM), an organizing directly engaged in anti-police brutality campaigns, standing outside the organization’s headquarters at 9211 Kercheval Avenue. The officers attempted to charge the political activists with loitering and impeding traffic, and four refused to comply, shouting, “We won’t be moved.” Their refusal to move sparked a three-day disturbance in the neighborhood surrounding AAYM headquarters as young African American residents expressed their collective frustrations with the police department.

The liberal "get-tough" policies enacted between 1964 and 1966 gave police officers the legal tools to control the everyday movements of the residents of Detroit. It is difficult to measure the extent to which these ordinances deterred crime, as Mayor Cavanagh and Commissioner Girardin promised they would. Despite this, it is clear that police officers used the anti-loitering and anti-knife ordinances to interrupt people on their way home from work, to stop teenagers from socializing on street corners, and to confront activists who objected to police misconduct. This expansion of police power contributed to the deep mistrust that existed between police officers and the African American community, especially in the poorest black neighborhoods targeted most in the War on Crime.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Mel Ravitz Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Chronicle

The Black Vanguard

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library