3. Government Investigations and Civil Rights/Black Power Pushback

Government agencies, private organizations, and the news media conducted many different investigations of the causes of the "Detroit Riot" of July 1967 and the solutions for the "urban crisis." Even before the city had stabilized, Governor George Romney and Mayor Jerome Cavanagh launched the New Detroit Committee to lead the task of rebuilding Detroit and bridging the massive racial gulf. President Lyndon Johnson also established the Kerner Commission to investigate the causes of the "civil disorders" in Detroit, Newark, and other American cities.

This page covers the immediate reactions of Mayor Cavanagh and Governor Romney as well as the extremely divergent assessments provided by the Detroit Police Department, the Detroit Urban League, and Black Power leaders in the city. The subsequent pages in this section examine the New Detroit Committee and Kerner Commission in more depth.

Verdicts from Mayor Cavanagh and Governor Romney

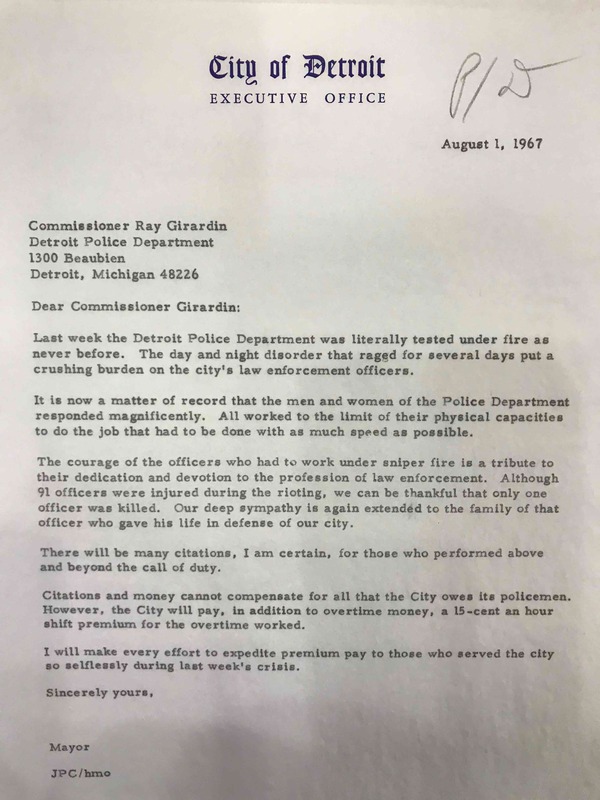

First, before anything else, Mayor Jerome Cavanagh praised and absolved the Detroit Police Department (right). The mayor thanked police officers for their "courage" and professionalism in protecting the city while facing sniper fire, a threat that was greatly exaggerated and had rationalized some of the police department's most egregious abuses of civil liberties and even murder. For the mayor, the DPD had "responded magnificiently." A few days later, facing fierce criticism from civil rights groups, the mayor promised a full investigation of alleged police mistreatment of civilians, which never happened.

On August 15, Cavanagh testified to the Kerner Commission (below gallery, far right). The mayor opened by telling the commission that he had been warning about the urban crisis for years and then said:

Cavanagh said that police brutality had not started the riot, and neither had black power extremists. To defend the DPD, the mayor boasted about its successful suppression of the Kercheval unrest in 1966 and explained that the city had the nation's most sophisticated riot prevention plan in place. And yet, this time the police department could not control the eruption in the ghetto. Why not?

The problem, Cavanagh concluded, was "the shared experience of slum living"--"the overall conditions of degradation and disorganization and poverty in which the young . . . grow up without any hope of legitimately sharing in the supposed fruits of a highly wealthy, materialistic society." It was "this slum atmosphere of the ghetto which breeds and cultures the extremists, the militant haters and the social outlaws and demagogues who regard the violation of the law and violence as really their only way of making their mark and obtaining their share." The immediate cause, in other words, was the young African American males, under the age of 25, who had no hope and felt extreme anger. (This is an explanation that historians such as Elizabeth Hinton call a "racial pathology" thesis--how liberals who cited root causes of poverty and racism also specifically blamed the alienation and criminality of young black males, justifying crime control as the main solution).

Cavanagh's get-tough militaristic policing had inflamed racial tensions in Detroit, but the mayor did not consider the police department to be a major part of the problem. Instead, he believed that the DPD was on the front lines fighting the ghetto criminality that broader social conditions and racial inequality had created. The mayor emphasized that rioting had to be met by a strong police response, but the long-term solution was racial equality that included more jobs, better housing, educational improvements, and higher levels of integration for the African American community. Cavanagh called for doubling down on his liberal antipoverty agenda and for achieving a society based on equal opportunity. At no time did the mayor address the pervasive problem of police brutality or acknowledge that the substantial reforms he proposed for housing, schools, and jobs might also be required for the DPD.

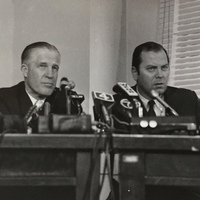

Governor George Romney laid out his interpretation during a press conference on July 31, the day after the last Army troops left the city of Detroit. The Republican governor defended his actions and in particular took credit for the rapid mobilization of the National Guard on July 23. He also criticized Lyndon Johnson for not sending in the U.S. Army sooner and stated, "the President of the United States played politics in a time of tragedy and riot."

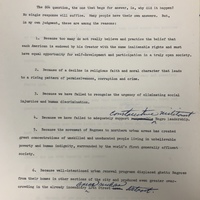

A few days later, Romney drafted a speech that asked, "why did it happen?" The governor acknowledged racial inequality but also primarily blamed criminal activity of black residents of the ghetto, which he attributed to a decline in religion and morality (gallery below). Among the 16 reasons Romney cited were:

- Racial discrimination and lack of equal opportunity

- "Decline in religious faith and moral character that leads to a rising pattern of permissiveness, corruption, and crime"

- Clustering of "unskilled and uneducated" black migrants from the South in northern ghettoes

- "Too many Negroes have become supersensitive to race even to the point of defending those guilty of violating the law and even advocating violence and revolution"

- "Longstanding friction between the Negroes and a predominantly white police force"

Detroit Police Department: "Responded Magnificiently"?

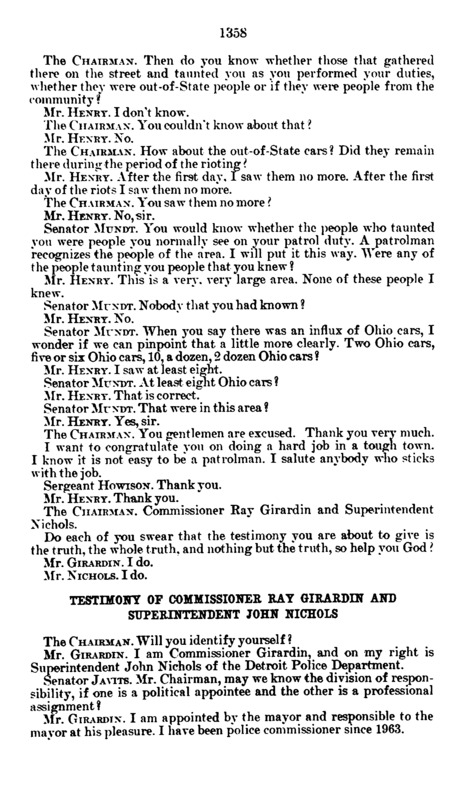

In the Kerner Commission hearing, Mayor Cavanagh again defended the DPD against critics who argued that the police should have started firing on the "rioters" and "looters" on Sunday morning, July 23, to suppress the unrest before it spread. Commissioner Girardin also told the Kerner Commission that if the DPD had started shooting, it would have been a bloodbath and many officers would have died as well. Girardin even commented that "many of the people looting were hard-working, decent, law-abiding citizens, that got caught up in this fever."

Neither the mayor nor the police commissioner acknowledged the fact that DPD officers killed at least 22 people, mostly unarmed "looters," as they praised the police department's self-restraint. Girardin even told the Kerner Commission that his force believed in "human life above property values."

Commissioner Girardin did strongly criticize the undertrained National Guard and acknowledged that "a great deal of the reports we had of sniping were jittery Guardsmen firing the gun, and this brings others firing their guns."

Mayor Cavanagh did ask his staff to write an assessment report on the DPD's performance during the civil disorder of July 1967. This was not the investigation of police brutality and misconduct that he had promised community activists. Instead, the evaluation methodically traced the sequence of events during the July 23 raid on the blind pig and its aftermath (this section is in the gallery on the 12th Street Blind Pig page). The staff report, completed in December 1967, mainly considered how the DPD response could be more efficient in the event of a future disturbance, such as better communications protocols and fewer logjams in the event of mass arrests.

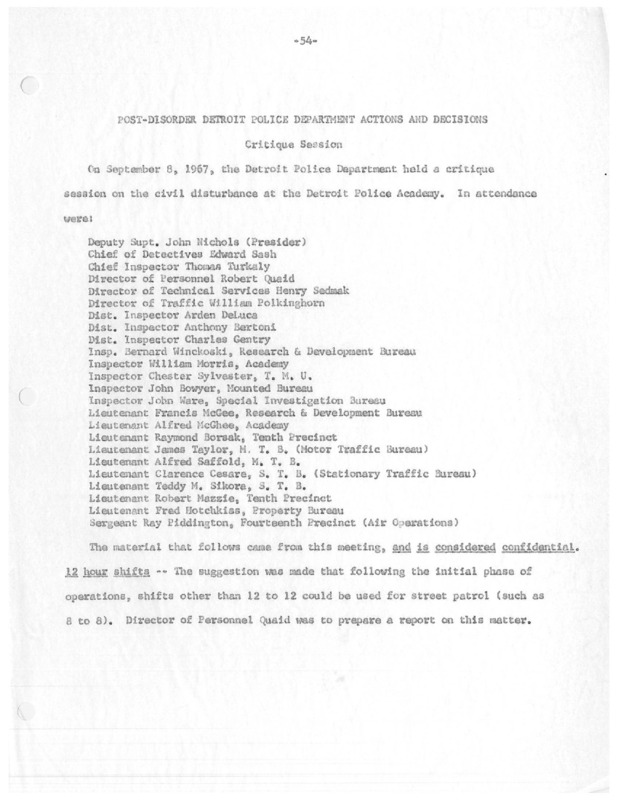

The appendix of the report, labeled confidential, recounted a "critique session" of the DPD performance by 24 of its ranking officers, led by Superintendent John Nichols. The evaluation revealed that the DPD, despite its public insistence on its professionalism and competence, acted in a disorganized fashion with many breakdowns in the chain of command, in which officers on the streets used their discretion to make policy on the ground. (The DPD self-analysis did not include any reflection on the civilians killed or wounded). The officers in the confidential session recommended that in a future riot control situation, the DPD should:

- Utilize 8 hour not 12 hour shifts (cutting down on officer fatigue)

- Clarify chain of command for all units in the field

- Maintain records on the weapons deployed and used in an emergency

- Reconsider allowing police officers to use their private weapons

- Obtain a helicopter or other aircraft

- Come up with a better system to transfer and track prisoners in an overflow situation

- Come up with a better system to identify dead and injured people

- Improve communications equipment

- Not overreact to "officer in trouble" calls with far greater response than needed

- Not overstate the actual threat in "intelligence" reports from the field [the hype about snipers is an obvious context here]

- Create a better system for liaisions with the National Guard

- Improve the procedures for mass arrests [such as at the blind pig]

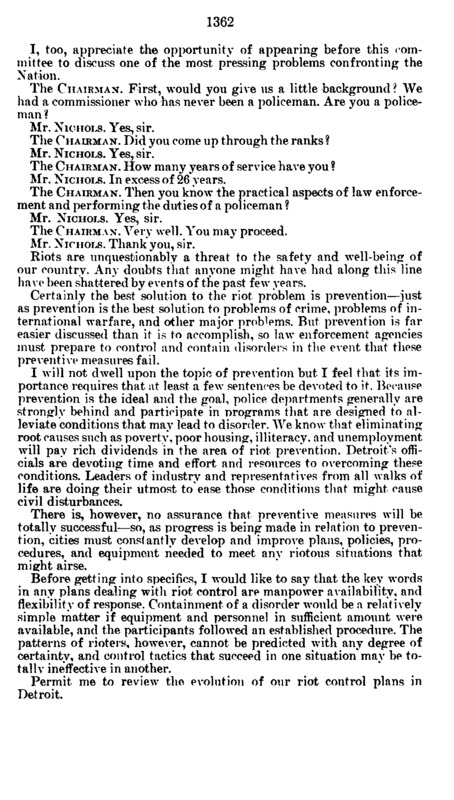

Publicly, according to the DPD, its officers "responded magnificently." In March 1968, Police Commissioner Ray Girardin and DPD Superintendent John Nichols testified to a congressional committee probing the Detroit riot as a "criminal disorder." Girardin protrayed Detroit as a city with excellent police-community relations as well as a sophisticated riot prevention plan that had succeeded so well during the Kercheval Incident of 1966. He labeled the "spontaneous" response to the raid on the blind pig as an unforeseeable incident that allowed "opportunists" and "extremists" to bring violence to the streets of Detroit. Girardin promised that the DPD would maintain law and order and that "violence, riots, looting, and burnin cannot be tolerated."

Superintendent John Nichols, a hardliner who later served as police commissioner during the STRESS era, was responsible for operational control of the DPD during the Uprising. Nichols testified to Congress that an agitator outside the blind pig "urged the crowd to violence by the age-old harangue of 'police brutality," and that the DPD's usual techniques failed because of the "hostility and belligerence" of the crowd. He also blamed insufficient manpower on a Sunday morning, requiring intervention of the National Guard and the Army. Nichols said the DPD had prepared for the future by acquiring more tear gas, military vehicles, communications technology, and other equipment designed to maintain law and order by force. He concluded by praising the DPD's magnificent response to the "violent and savage riot."

Detroit Urban League: What Causes Rioting?

The Detroit Urban League (DUL), a moderate and business-oriented civil rights organization, produced a major investigation report called "The People Beyond 12th Street: A Survey of Attitudes of Detroit Negroes after the Riot of 1967." The survey's main findings emphasized that the rioters and looters were angry youth who did not represent the vast majority of African Americans in Detroit. As the DUL emphasized:

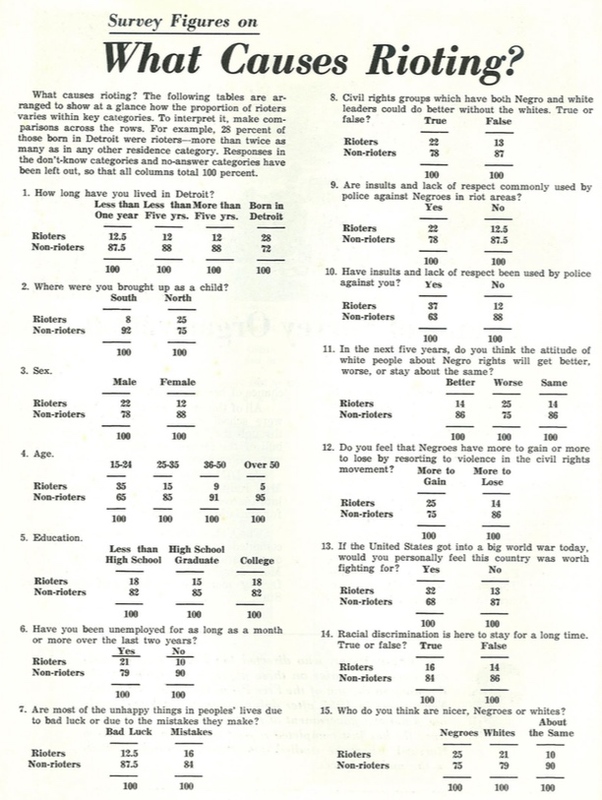

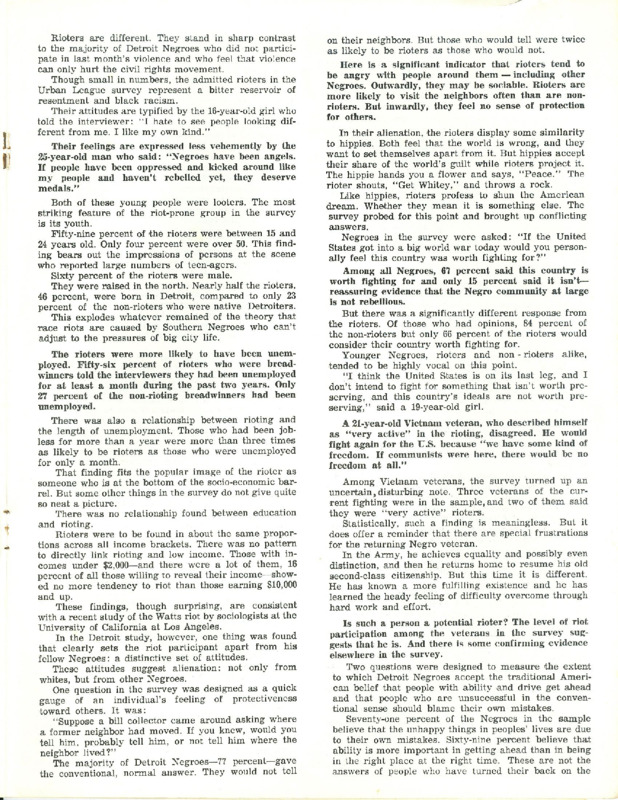

1. Who were the rioters? The DUL surveyed residents of the main "riot areas" on the East and West sides and found that the majority of the rioters were youth between the ages of 15 and 24 and that 60% were male. The typical rioter was born in the North and was more likely to be unemployed than a non-rioter. The survey also found that the rioters were more deeply alienated from American society and "susceptible to the black nationalist philosophy that the law and order of a white-built society is not worth preserving" (see first two documents in gallery below).

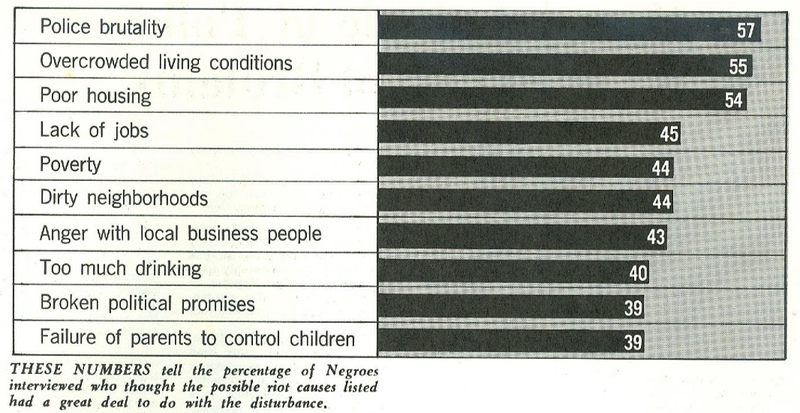

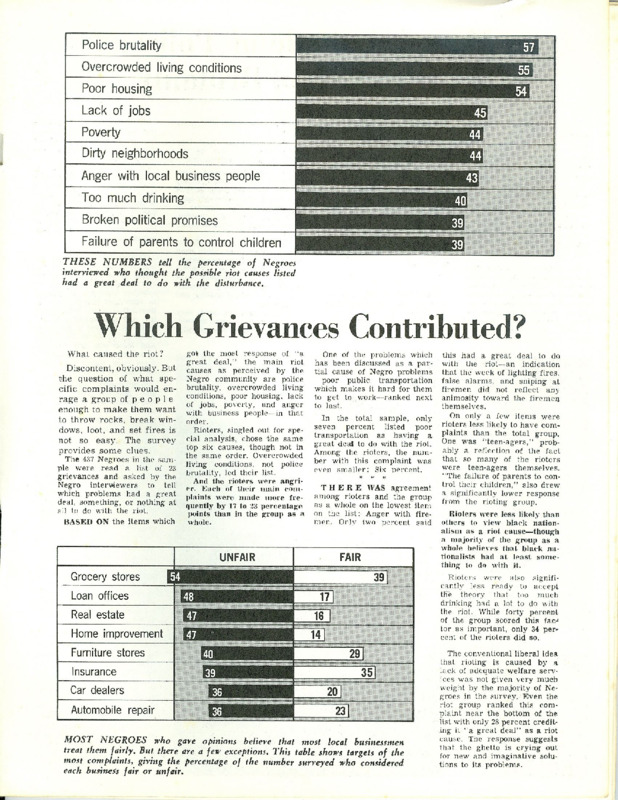

2. What were their grievances? The DUL report also asked African Americans who rioted, and those who did not, to identify the main causes of the civil unrest. The majority identified police brutality, with crowded and poor housing close behind, followed by unemployment and poverty (see right). The rioters were the most likely to highlight police brutality and housing inequality, but a majority of all residents of Detroit's black neighborhoods agreed with these causes. Anger at "slumlords" and exploitative businesses was a real factor, but not one cited by the majority. Older African Americans were the most likely to emphasize unruly teenagers by choosing the answers about too much alcohol and not enough parental control.

The report highlighted the central role of police brutality, a marked contrast to the interpretations of Mayor Cavanagh and the DPD itself. In the survey, 82 percent of respondents considered police brutality to be a primary or secondary cause. For the black residents of Detroit, police brutality was a "hostile racial attitude"--"a state of mind found in police individually and collectively." The report's list of examples included:

- "Arbitrary rousting and frisking and beatings"

- "Stopping and searching cars unnecessarily"

- "Unnecessary personal frisking and searching"

- Insults and "lack of respect"

- Corruption that allows prostitution to flourish in black neighborhoods

- Failure to investigate crimes with black victims

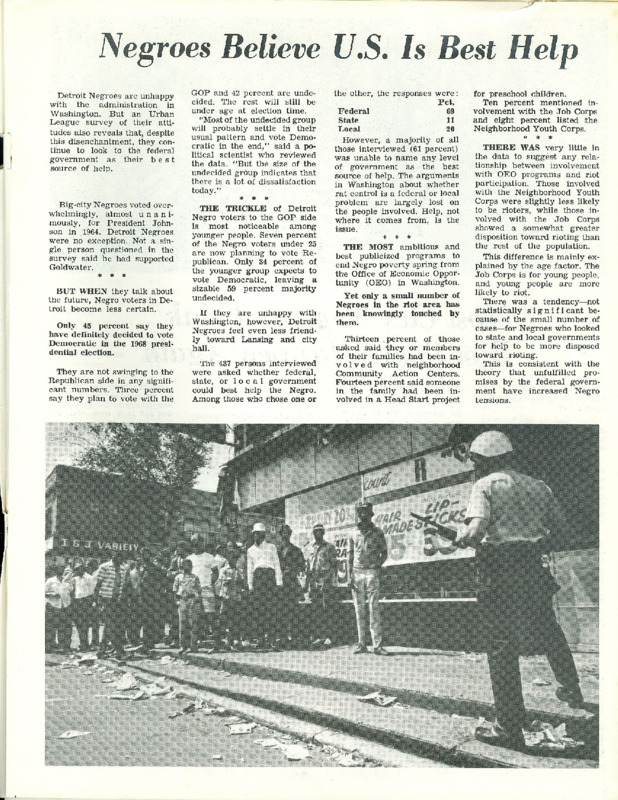

3. What are the solutions? Finally, the DUL report warned that federal antipoverty programs had not made a noticeable difference in the lives of most African Americans in Detroit. Most of the black residents surveyed (84%) also believed that another riot was possible, perhaps even likely, if the government and white society did not change course and make the situation better.

The Detroit Urban League concluded the report with a reassurance and a warning. The reassurance was that the rioters were "a deviant minority within a law-abiding Negro community" and that the "strong Negro middle class" remained strongly opposed to violence and black nationalism. The warning was that police brutality, more than any other factor, had caused the breakdown of civil order, in the context of deep frustration and alienation by an "under-class" that lived in poor, racially segregated neighborhoods and had lost faith in American society. "This means," the DUL declared, "that if the attitudes of alienated young Negroes are to change, the attitudes of the rest of society must change."

Read the full Detroit Urban League survey in the gallery below.

Black Power

In 1968, CBS-TV ran an investigative report on the Detroit Uprising and the Kerner Commission investigation called "Remedy for a Riot" (watch the full program here). The documentary found that "friction with the police was not the cause but only the latest in a chain of causes." The CBS report criticized the DPD and the National Guard for overreacting and "responding with a violence out of proportion with the threat," especially regarding alleged snipers, and sweeping up "many innocent bystanders" with indiscriminate mass arrests.

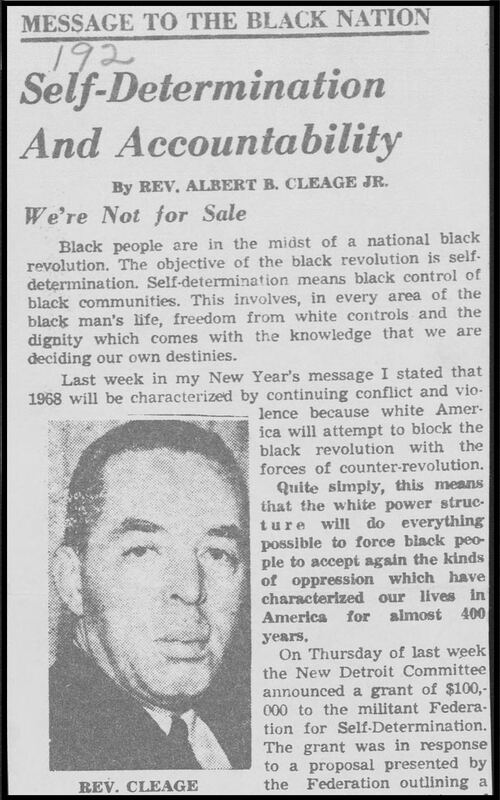

CBS-TV also gave a platform to one of Detroit's most influential black power leaders, the Rev. Albert Cleage, who had played a major role in organizing the 1963 Walk for Freedom and the subsequent protests after the Cynthia Scott murder by a DPD officer. Unlike the Detroit Urban League, and other traditional black leaders, Cleage did not have a formal role on the New Detroit Committee. But Rev. Cleage and the black power philosophy that he represented was a force to be reckoned with in Detroit and would become increasingly influential over the next few years as radical politics flourished.

On Auust 9, 1967, Cleage and other black radicals met to form an alternative to the New Detroit Committee, the business-dominated recovery organization established by Mayor Cavanagh and Governor Romney. Cleage and his allies formed the City-wide Citizens Action Committee, and later the Federation for Self-Determination, and demanded control of funds for their community-based initiatives.

Rev. Albert Cleage argued that white liberals such as Mayor Cavanagh, and the white business leaders in charge of the New Detroit Committee, did not "understand anything about the black community." Cleage explained that "the basic problem, and not only in Detroit but throughout America for black communities is that . . . the black man now wants freedom, equality, but in a sense that the white man doesn't even understand. He wants dignity, he wants control of black communities. That's why the word 'black power' is meaningful to black people and frightening to white people. Black power means the power to control your own destiny; that's what black people want. They want to control the communuty, the economics of the community, the politics of the community."

For Cleage, black power was a specific political program that meant self-determination and community control of community institutions: "We're tired of having white representation . . . downtown in city government, we're tired of having white merchants take care of our business, we're tired of having white teachers in our schools, white principals, white administrators. We want all of this to be black, because this is a black community."

Sources

Civil Rights during the Johnson Administration, 1963-1969, Part V: Records of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission), Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas (ProQuest History Vault)

Detroit Urban League, “The People Beyond 12th Street: A Survey of Attitudes of Detroit Negroes after the Riot of 1967,” 1967, Box 1, Joseph L. Hudson Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2007)

Jerome Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Image Gallery, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

General Photographic Collection, Michigan State Archives, Lansing, Michigan

George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

CBS-TV Special Report: “Remedy for a Riot” (1968), Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/remedyforariot

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)

Hubert G. Locke, The Detroit Riot of 1967 (1969, reissued 2017)