2. Limits of Police Reform

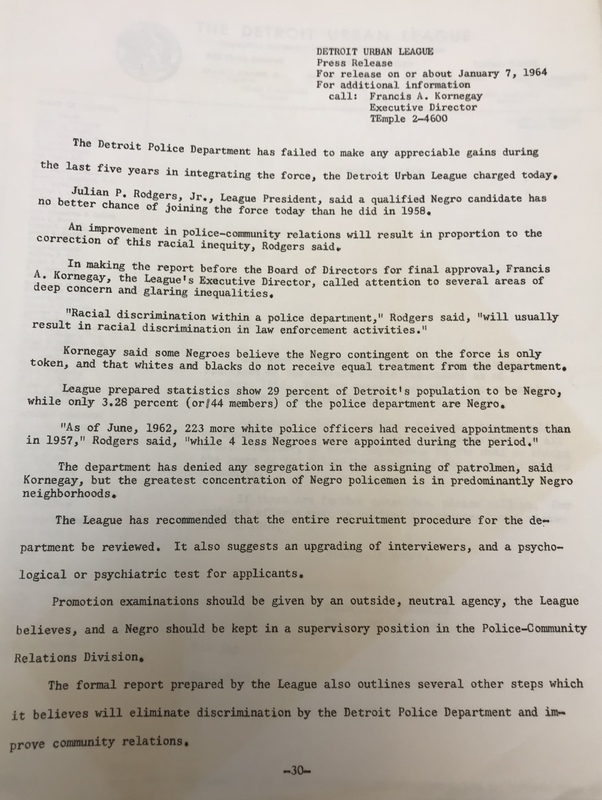

- Detroit Urban League President Julian P. Rogers, January 1964

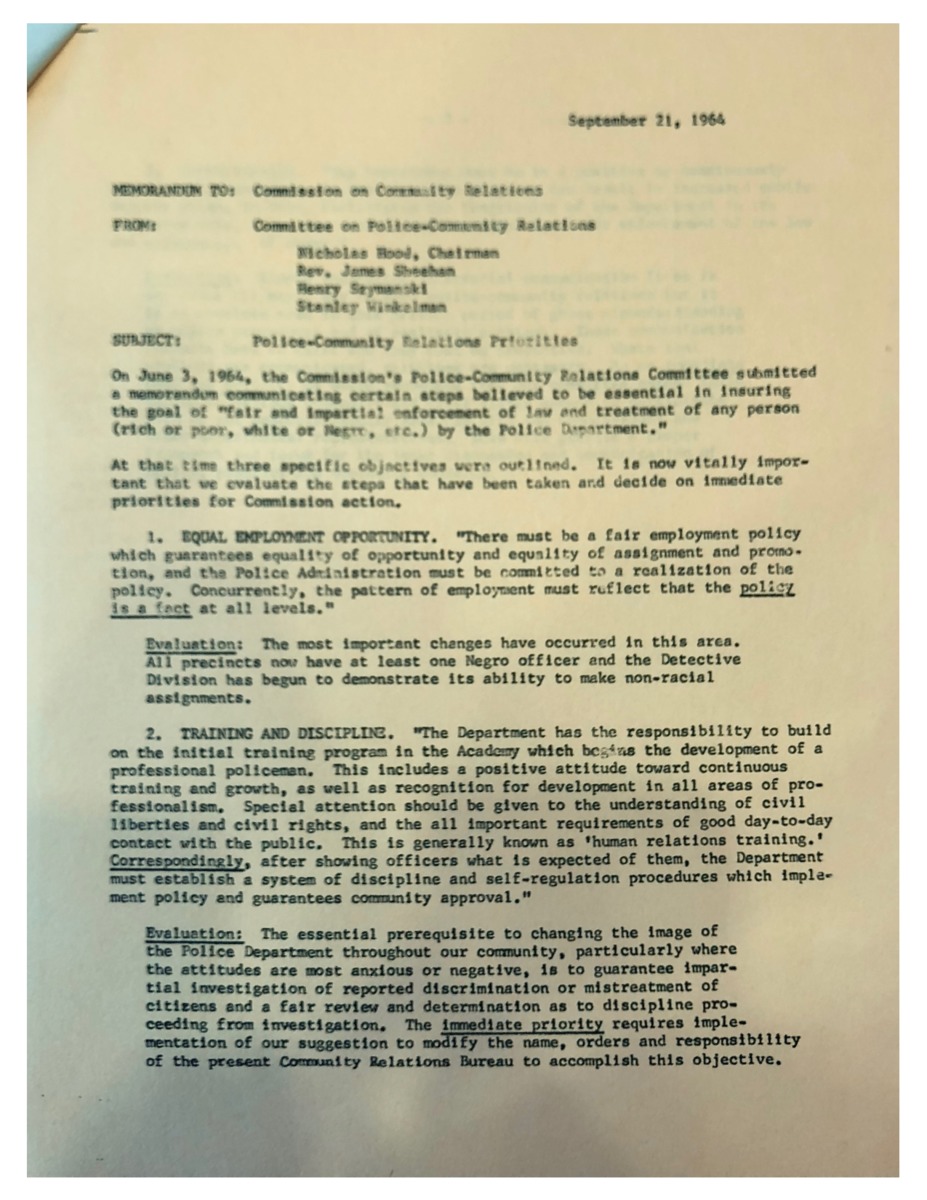

Of the many voices influencing police reform in the mid-1960s, civil rights groups were the most vocal in exerting pressure on the DPD and challenging its desire to keep reform an internal issue. The mainstream civil rights groups--especially the Detroit chapter of the NAACP and the Detroit Urban League (DUL), along with their allies in the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)--pressed a liberal reform agenda that included recruitment of more African-American officers, improved and more frequent police-community relations training, updates to the training and qualification standards of recruits, and fair investigations of allegations of police brutality and misconduct. The limited ability of liberal reform efforts to substantively change the DPD gave rise to more confrontational left-wing and black power organizations that called for a much more radical overhaul of the police.

Demands to Diversify the Force

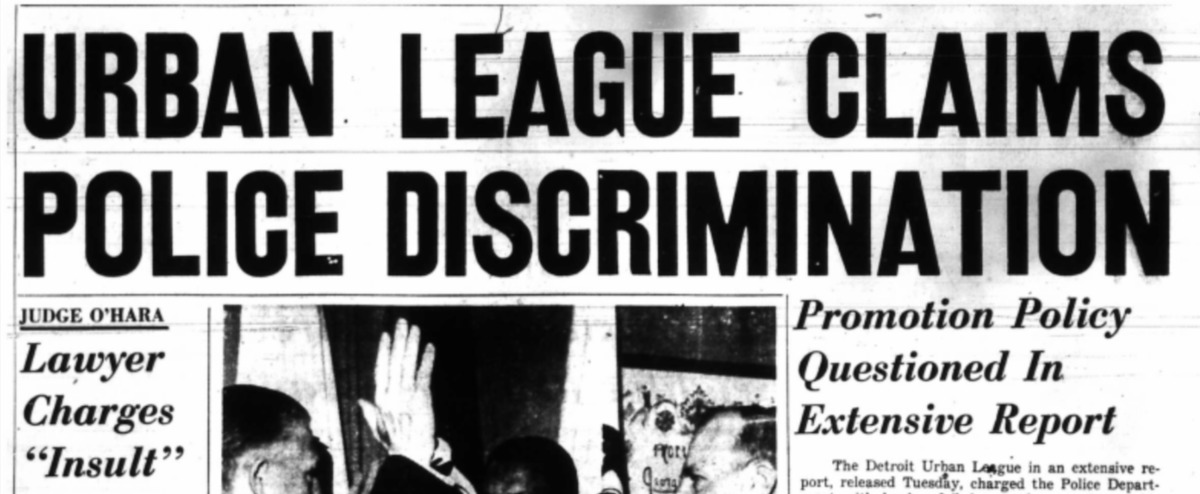

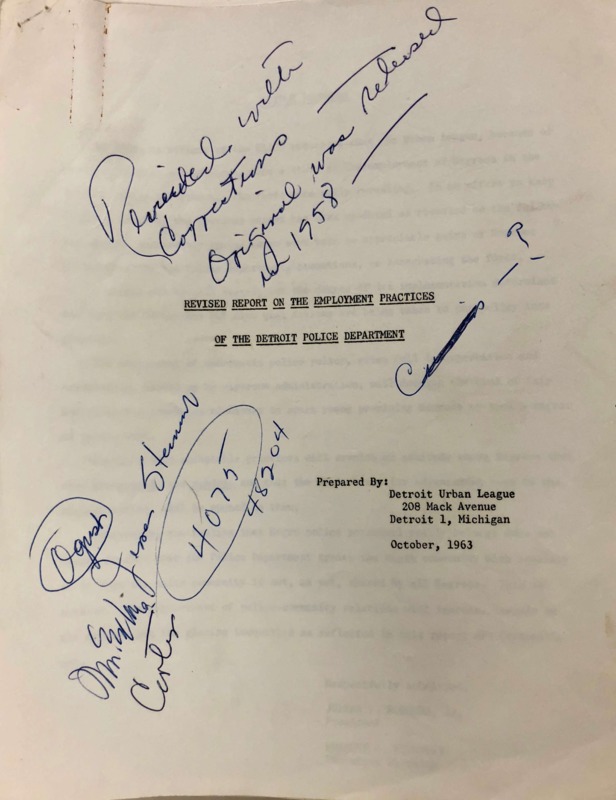

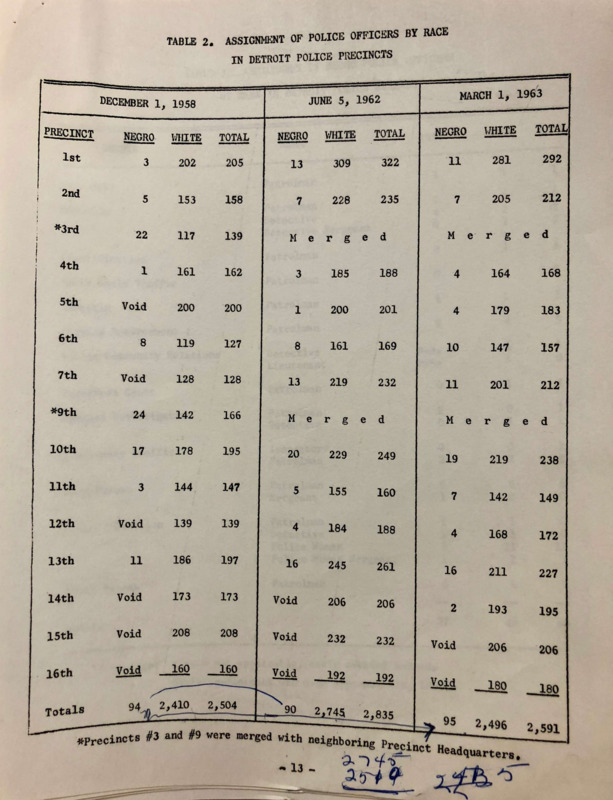

Mainstream civil rights groups encouraged the Detroit Police Department to hire more African American officers as a means of improving police-community relations, as they has been doing for decades. Despite official claims that the DPD had made intensive efforts to diversify its police force, a Detroit Urban League study from January 1964 revealed that out of 4,390 Detroit police officers, only 144 were African American, the same number that the DUL reported five years earlier in 1958. The DUL described this statistic as evidence that the DPD had failed to put its official policy of non-discrimination into practice. The Detroit NAACP endorsed the study and its recommendations, although officials from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (who were appointed by the mayor) described it as merely a “statistical survey” that failed to capture the city’s progress toward better police-community relations.

The report’s allegations of discriminatory practices within the DPD attracted widespread attention from major newspapers, including the African American-owned Michigan Chronicle, which agreed with the report’s statistical findings but disagreed with the DUL’s decision to use them to confront the DPD. In an editorial, Ofield Dukes remarked that because police reform “remains one of our most sensitive, explosive, and complex community problems,” solutions should be made through “coordination and cooperation” with the DPD and community partners. Patrolman Avery Jackson, an African American officer in charge of recruitment, stated in an editorial in the Chronicle, “We have been to the Urban League numerous times; we have visited bowling alleys where we have left literature and brochures; we have used radio stations and newspapers; we have contacted the churches, . . . but the great scarcity of applicants, whether Negro or white, remains.” Dukes suggested that the reason for this might be that African American men were not interested in working for low wages in a hazardous environment “controlled rigidly by a hierarchy of racially-prejudiced police officials.”

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon, an African American military veteran who grew up in Detroit and joined the police force in 1965, described a situation of almost constant racism from white officers. (Watch a video excerpt from our 2019 interview with McKinnon at the bottom of this page). On his first day, the white officer assigned to be in the squad car with McKinnon expressed disgust, called him a n----- at roll call, and refused to speak to him throughout the eight-hour shift. In his memoir, Stand Tall, McKinnon recalled that "there were many wonderful people in the department," but also many white officers who tried their hardest to isolate and mistreat their black counterparts:

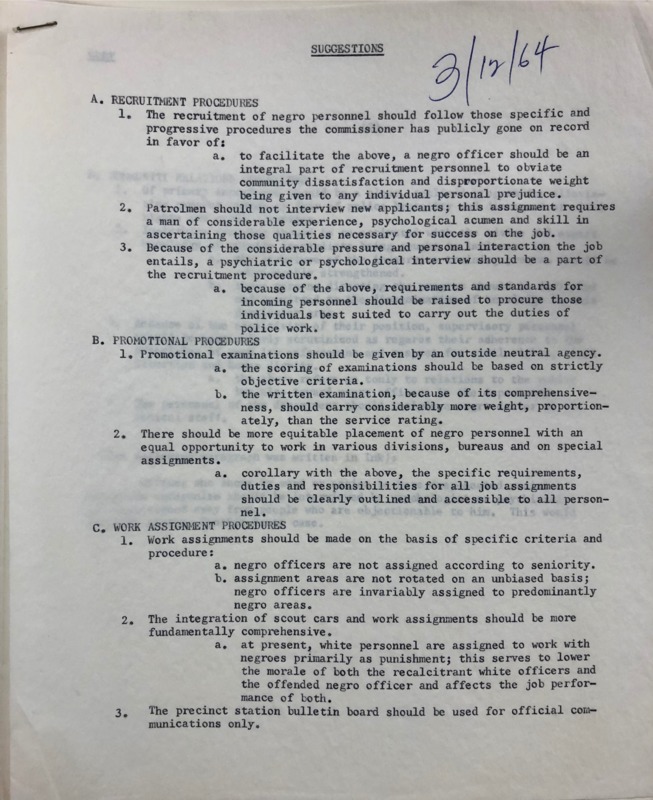

In a series of meetings with DUL officials, Police Commissioner Ray Girardin denied the presence of discrimination in the DPD’s hiring policies but acknowledged that many Detroit police officers had racially biased attitudes. He agreed to consider the DUL’s suggestions, which included placing African American officers on the committees in charge of hiring and promoting officers, integrating the Big Four cruisers and precinct offices, and assigning psychologists to interview officers who had revealed any evidence of “deep-seated racial prejudice.” Girardin ordered that the department intensify its efforts to hire African American officers, and one month later, two African American police officers were assigned to work in the 15th and 16th precincts, which had previously been all white. By raising public awareness of patterns of discrimination through this study, the DUL pressured the DPD to make small steps toward hiring a more diverse police force. However, racism and discrimination within the DPD were deeply-entrenched problems that could not be solved by reassigning a handful of officers to new precincts.

Human Relations Training

The DUL, NAACP, and DCCR also advocated increased use of human relations training for police officers. The hope was that through these trainings, the attitudes and perspectives of white officers would change in relation to entering low-income, African American communities. Additionally, reformers believed that the trainings would add to the professionalism of the police officers by decreasing their emotional and stereotypical tendencies in street incidents and encouraging them to approach their job unemotionally and objectively.

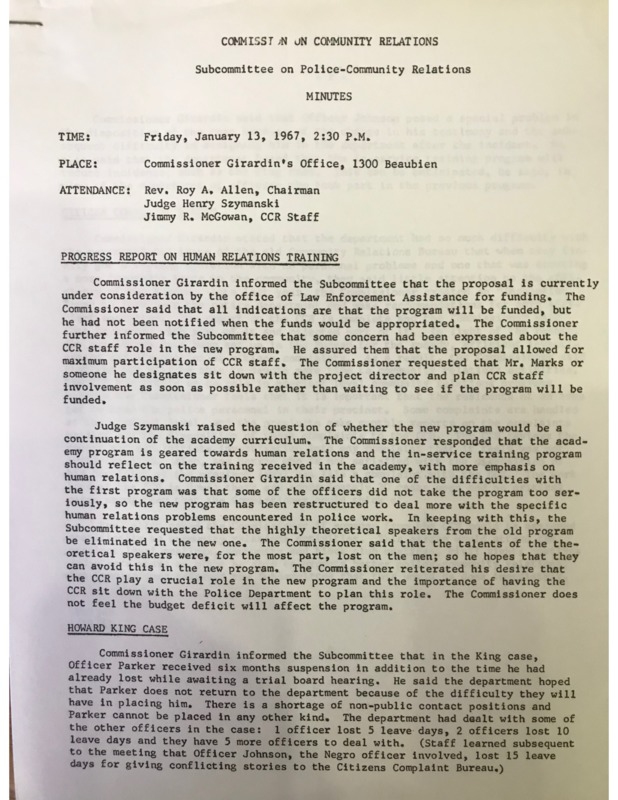

The DPD agreed to increase the amount and quality of human relations training thanks to pressures from these civil rights groups as well as trends in other states, federal recommendations, and a 1964-65 study by Greenleigh Associates. The Greenleigh consultant report pushed the DPD to seek a federal anti-poverty grant for police training to be conducted by the DCCR and Total Action Against Poverty officials. With the grant money, the DPD and DCCR embarked on creating officer training programs that combined lectures, discussion, and community participation. Officers attended the training seminars twice a week for four weeks.

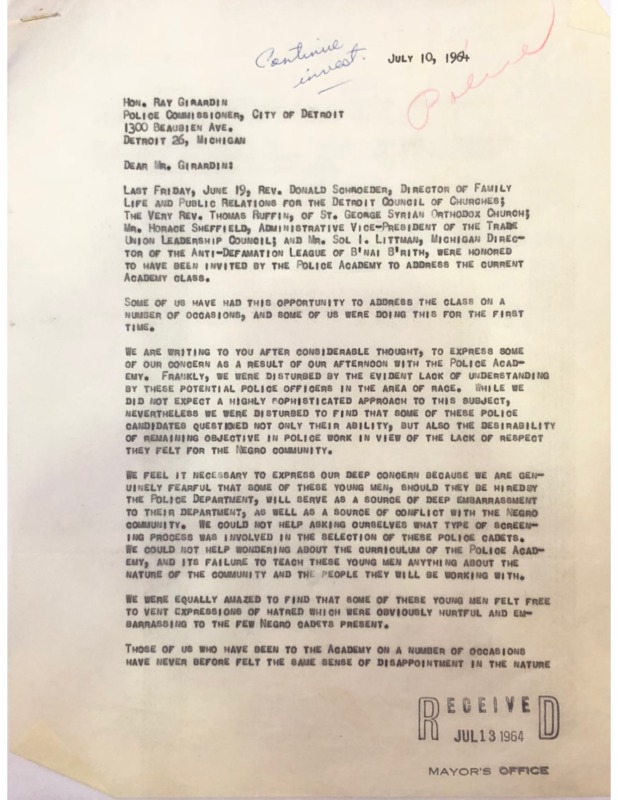

Despite the new human relations training program, the overall problem of poor police-community relations and racial discrimination persisted. A group of African American pastors, after addressing a class of police academy students, wrote to Commissioner Ray Girardin that they “were disturbed by the evident lack of understanding by these potential police officers in the area of race.” Furthermore, the ministers criticized the process for “its failure to teach these young men anything about the nature of the community and the people they will be working with.” Civil rights groups continued to request more frequent and effective human relations training to improve police-community relations, but they also recognized, as the last document in this gallery indicates, that rigorous investigations and firm discipline against police officers who brutalized and mistreated black citizens was also crucial.

Police Professionalization

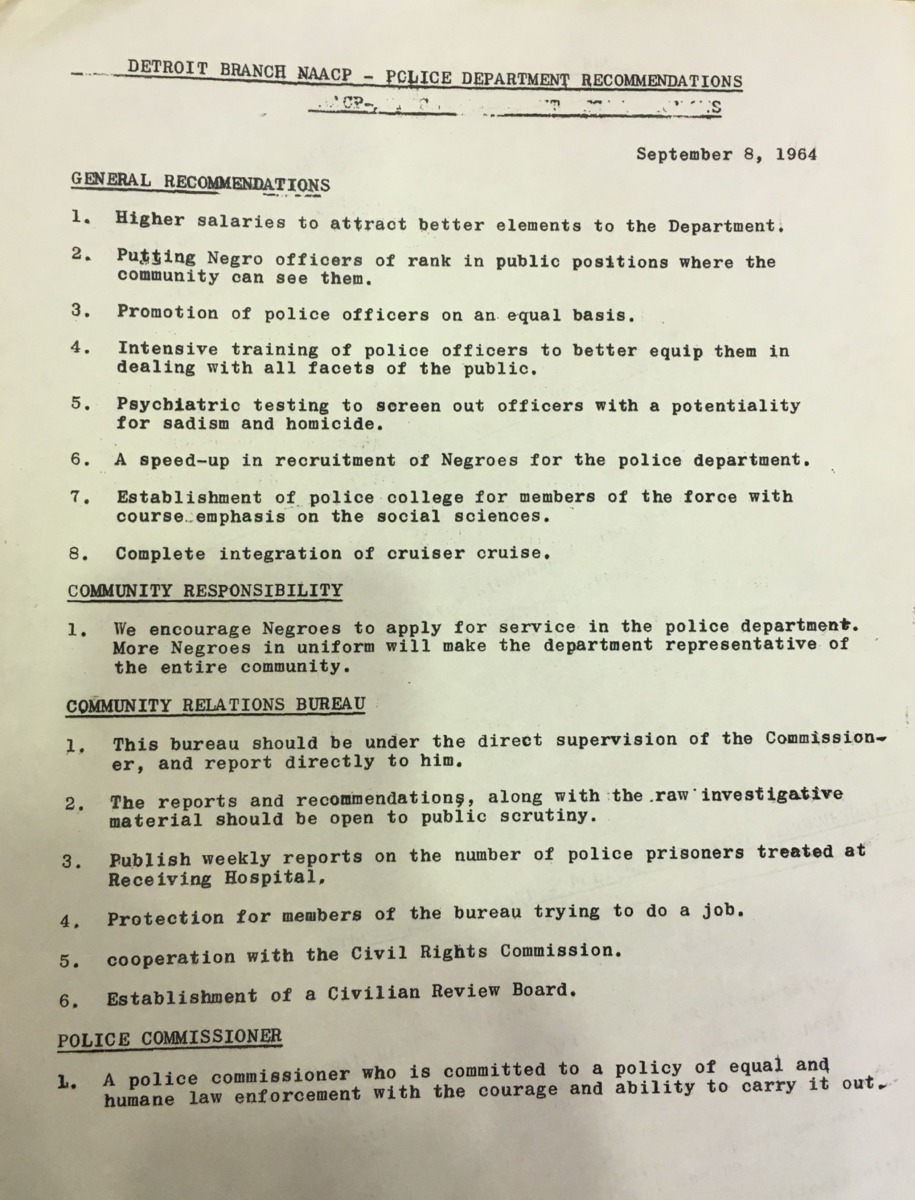

The Detroit Police Department was frequently criticized regarding their standards for new recruits. Qualifications included the equivalency of a high school diploma, physical aptitude, and no criminal record. Of those, the education of potential officers became a focal point in the reform debate. Commissioner Girardin defended the tests taken by potential recruits and argued that reducing education requirements would attract less qualified applicants. While the Detroit branch of the NAACP stressed the hiring of African-American policemen, they also urged recruitment reform and called for the creation of a police college in order to further educate recruits. Additionally, the NAACP recommended a psychiatric test to screen for violent and racist tendencies in applicants and favored increasing salaries to recruit better men.

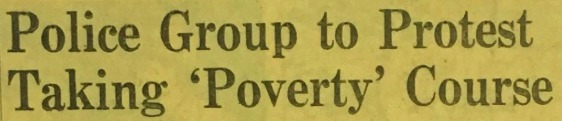

The DCCR and civil rights groups also called for increasing the professionalism of the DPD by teaching officers about civil liberties and constitutional rights of citizens. Many white officers resisted and resented these efforts, such as this headline of a group protesting a requirement to attend a course about poverty because of the increased tension between police and low-income black neighborhoods.

Ike McKinnon's Encounters with Racism as a DPD Officer

In this video excerpt (7 min.), Ike McKinnon describes his "very difficult" first days on the job as an African American DPD officer in 1965, including being subjected to numberous racial epithets and other abuse from white officers.

Sources:

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Urban League Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Francis A. Kornegay Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Chronicle, January 11, 1964

Detroit News, June 8, 1965

Isaiah McKinnon, Stand Tall (2001)

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon Interview, Part 1, December 3, 2019, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741