3. Mayor Cavanagh and Police Reform

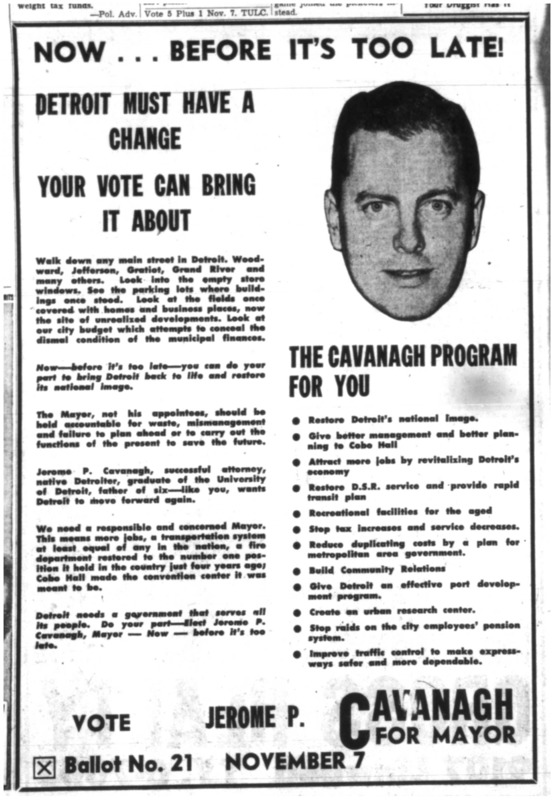

On November 7, 1961, when Jerome Cavanagh won the mayoral election of Detroit, many people were shocked. Cavanaugh ran as the antithesis of the Republican incumbent, Louis Miriani. He was a young, liberal Democrat, a supporter of civil rights reforms, and he advocated for better police and community relations. African Americans, and white liberal voters, rallied around his campaign. For many commentators, Cavanagh seemed to be Detroit's version of President John F. Kennedy, a youthful Catholic politician, a father of six, an energetic reformer. Cavanagh ran on a platform of "Change," promising more jobs and a return of Detroit to the great city it once had been.

Cavanagh promised a "government that serves all its people" and improved community relations, which was the language at the time for better race relations. He received 85% of the African American vote. As a candidate and as mayor, Cavanagh pledged to repair the relationship between the black community and the city government, including the police department, that had been badly damaged by the crash program.

African American leaders were very enthuastic about the new mayor's promises and the potential for a better day for civil rights in Detroit. The NAACP praised Cavanagh, and the appointment of Edwards, expressing great optimism. The Michigan Chronicle reported that black leaders believed that Cavanagh "is concerned about all the problems of the community" which essentially meant that previous city leaders had only cared about the white community. State senator Charles Diggs said that "Negroes really demonstrated what can be done when we wake up and get together." A prominent black minister explained:

Police Reform: Promising "Equal Treatment"

When Cavanagh took office, he appointed George Edwards, a distinguished justice on the Michigan Supreme Court, to be the commissioner of the Detroit Police Department and to implement a reform agenda. Edwards was an outspoken white liberal who promised better police-community relations through equal enforcement of the law. Edwards and Cavanagh also recognized, as the police commissioner said in one early report, that the city of Detroit was "sitting on a powder keg" when they took charge. The previous years, and especially the brutal crash program, had led to "dangerous racial tension" and hampered effective law enforcement by alienating the black community at large.

Commissioner George Edwards promised a three-point reform program for the Detroit Police Department, which was really as much a philosophy of equality under the law as a specific agenda:

- "More law enforcement and more vigorous law enforcement."

- "Equal protection of the law for all citizens; equal enforcement of the law against all violators."

- "Encouragement of citizen cooperation in law enforcement."

It is striking, and revealing, that the white liberal promise of basic racial equality under the law, and enforcement of the constitutional rights of all citizens, would be seen as such a breakthrough for "community relations" in Detroit. Less than one year before Cavanagh's election, in December 1960, the NAACP and the Urban League had told the U.S. Civil Rights Commission that the city of Detroit was deeply and deliberately segregated in housing, education, and employment. The NAACP also had provided extensive evidence of the racist and segregationist aims of the Detroit Police Department, and this was before the crash program mobilized a biracial coalition of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations to demand reform and oversight of the DPD.

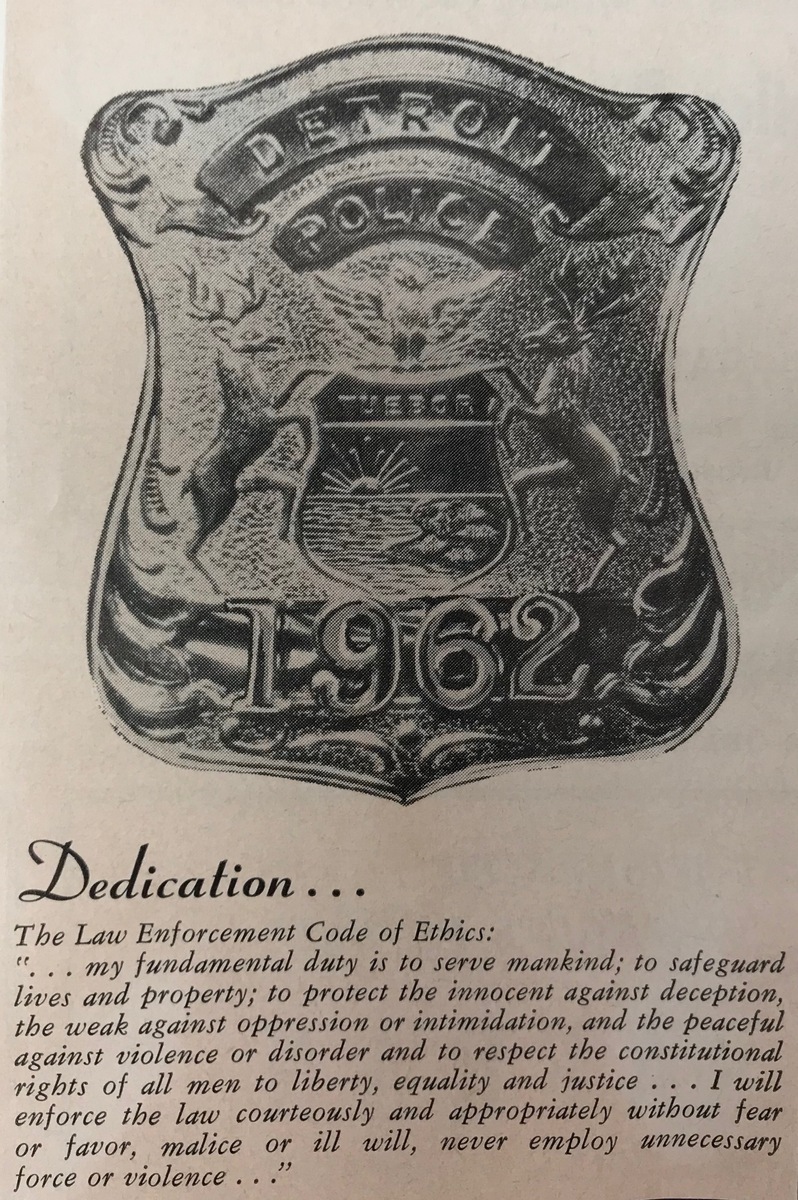

It is important to note that Cavanagh and Edwards did not endorse the most radical demand of the mainstream civil rights movement in the early 1960s: an independent civilian review board to investigate and discipline police for brutality and misconduct. Instead, the white liberal administration promised that the DPD would become a more professional and egalitarian organization, bringing about efficient and effective crime control through equal treatment under the law. If this was a liberal promise of a new direction in police-community relations, it is then worth recognizing that Edwards's reform agenda was essentially to enforce the "Law Enforcement Code of Ethics," in place since the mid-1950s, and to which every DPD officer already took an oath:

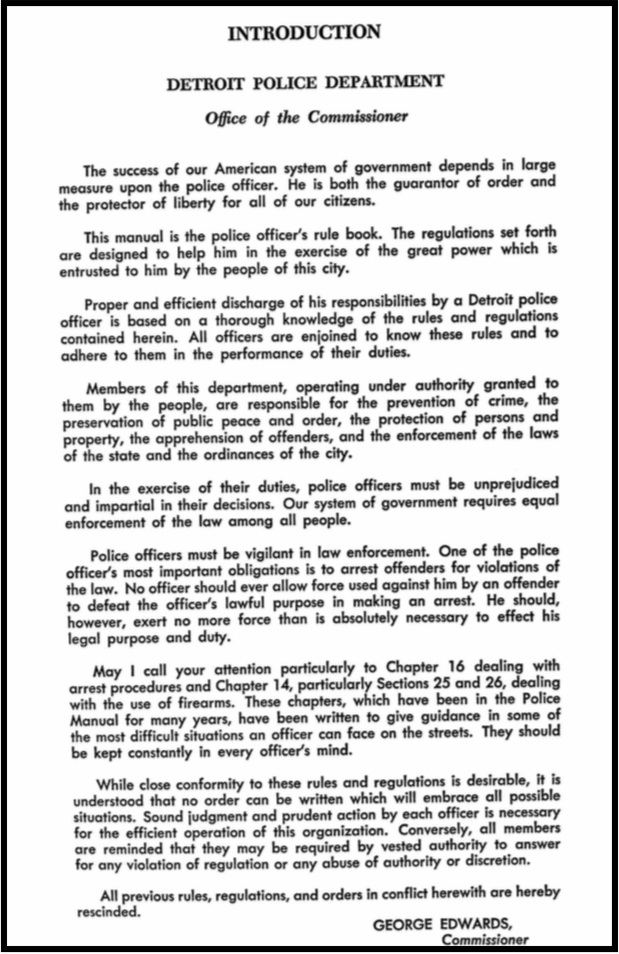

Commissioner George Edwards updated the DPD manual as part of his reform agenda when he took charge in 1962 (below left). In his introductory note, Edwards informed officers of their responsibility to protect citizens through "unprejudiced and impartial" decisions and to promote "equal enforcement of the law among all people." Edwards also refined and clarified the arrest and use of force procedures, to try to cut down on the widespread practice of illegal arrests and the often brutal treatment of people under suspicion and in custody. For these positions, Edwards received significant pushback from within the DPD and from white conservatives in Detroit's general population.

Commissioner Edwards and Mayor Cavanagh did make some real progress on the police-community relations front, at least in the first year and a half, but the turnaround would be short-lived. By the summer of 1963, both men faced fierce criticism from civil rights groups for the exoneration of a white officer who shot and killed an unarmed black woman. Edwards stepped down soon after, and the Cavanagh administration increasingly embraced a tough-on-crime agenda with little concern for civil liberties as racial turmoil intensified in the mid-1960s.

Sources:

Pittsburgh Courier, November 18, 1961

Michigan Chronicle, November 18, 1961

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Image Gallery, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Charles William Ungermann Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Mary M. Stolberg, Bridging the River of Hatred: The Pioneering Efforts of Detroit Police Commissioner George Edwards (1998)

Alex Elkins, “Liberals and ‘Get-Tough Policing’ in Postwar Detroit,” pp. 106-116, in Joel Stone, ed., Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies (2017)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)