Remembering STRESS Victims

Detroit police officers in the STRESS unit killed at least 22 people during its three years in operation and shot and seriously wounded dozens more. Almost all of the civilians casualities were African American males, many killed under conditions that indicated excessive force, "shoot-first" procedures, and planting of weapons at the crime scene. Two additional African American males, Mark Bethune and John Percy Boyd, were shot and killed by police officers in Atlanta after becoming subjects of an intensive STRESS manhunt. One of the deceased victims was an African American law enforcement officer shot by a plainclothes STRESS unit in mysterious circumstances, and at least two of the civilian fatalities arguably involved premeditated murder. Three STRESS officers also died of gunfire, at least one in suspicious circumstances, although no policemen was killed or even injured during the undercover decoy operations that became STRESS's deadliest legacy.

The controversial decoy tactic accounted for a majority of STRESS homicides, including nine of the first ten during the most deadly period, the spring and summer of 1971. The death toll diminished after the protests and civil rights investigations that followed the killings of teenagers Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell that September. But the Detroit Police Department resisted demands for reform and did not modify the STRESS decoy operations until the massive backlash that accompanied the Rochester Street Massacre of March 1972 (covered in the next section), when STRESS officers killed a Washtenaw County Sheriff's deputy in a murky incident that brought allegations of narcotics corruption in the DPD.

STRESS Shootings: A Suspicious Pattern of Excessive Force and Framing of Victims

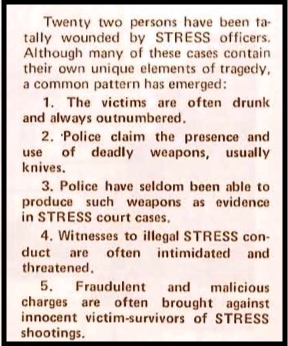

The homicides by STRESS units followed a suspicious pattern of police criminality, as the Labor Defense Coalition documented in its 1972 lawsuit seeking the unit's abolition and as the affiliated activists in From the Ground Up emphasized in its 1973 expose "Detroit Under STRESS" (excerpt at right).

- First, undercover STRESS officers generally instigated and escalated the encounters that they then blamed on attacks by "muggers" and "street criminals," usually causing the targets to flee from armed men they did not necessarily realize were law enforcement. Many incidents happened late at night, targeted African American panhandlers or inebriated males leaving bars, and appeared driven by the collective white law enforcement sentiment that all Black males out on the inner-city streets after dark were presumptively criminals.

- Second, the STRESS units began firing their weapons as a first rather than a last resort, often shooting fleeing suspects in the back, and in several cases shooting them in the front from close range, based on the "proactive policing" philosophy of controlling the streets through preemptive violence.

- Third, the STRESS unit would 'discover' an allegedly deadly weapon on the deceased civilian, usually a knife, which the Homicide Bureau and Wayne County Prosecutor then cited to justify the shooting. There is no recorded case of a police officer injured by a knife wielded by someone subsequently killed, a pattern that defies logic, as the Labor Defense Coalition pointed out in its 1972 lawsuit. Anti-STRESS activists accused police officers of planting such "drop" weapons on civilians after a shooting in order to clean up the scene and cover up the investigation, and incontrovertible evidence emerged in 1973 that Patrolman Raymond Peterson, the deadliest STRESS officer, did so. (Jeffrey Patzer, a DPD officer who resigned in 1973 after reporting a police brutality incident, told a journalist that police academy instructors advised him to carry a knife while on duty in case he shot an unarmed civilian. In an interview with our project, a former Detroit crime reporter confirmed the common knowledge that some officers habitually carried "dropsy" knives or guns in order to frame suspects and exonerate themselves in cases of a questionable or 'bad' shooting).

- Fourth, STRESS units often intimidated witnesses to questionable shootings, and the DPD and county prosecutor frequently brought false charges against the victims, in order to cover up what really happened. In one case, STRESS officers even allegedly murdered the witness to a previous homicide.

Despite these suspicious patterns, the Wayne County Prosecutor found all but one STRESS homicide to be justified: the eighth fatal shooting involving Patrolman Raymond Peterson, after forensic evidence proved that he had planted a knife to frame the victim. The Labor Defense Coalition, in its lawsuit seeking the abolition of STRESS, named Prosecutor William Cahalan as a defendant and accused him of orchestrating a "systematic and intentional scheme to rubber-stamp fradulent police complaints against innocent civilians and to avoid, whenever possible, prosecuting police officers whom he knows and has reason to know are guilty of vicious criminality."

This map provides a visual representation of all 22 identified STRESS fatalities between 1971 and 1973 (a map also including non-fatal STRESS shootings is in a section below). Hover over the dots for brief descriptions of each incident, and continue below for more substantive accounts and supporting documents. Zoom to view the clusters of fatalities near the downtown and midtown business corridors, which activists charged was a strategy to protect white property investments rather than Black crime victims. Also note another cluster of three STRESS fatalities on the far East Side of the city, in the zone between racially transitional neighborhoods and the all-white Grosse Pointe suburbs, and also two decoy shootings in a commercial district along the color line just east of Hamtramck and south of the city airport. The darkest blue-shaded areas represent the most racially segregated African American neighborhoods; note how most fatalities occurred along the color line or in the business corridors.

Map of 22 STRESS Fatalities, 1971-1973, in Detroit's Racial Geography (1970 Census)

- Black circles (14) = Fatal shooting by STRESS undercover decoy operation (two circles indicate the killing of two people in the same incident)

- Red circles (8) = Fatal shooting by non-decoy STRESS unit

1971: Fourteen Civilian Fatalities

The Wayne County Prosecutor exonerated all of the white STRESS officers who participated in the killings of fourteen civilians, all but two African American males, during 1971. In the Labor Defense Coalition's abbreviated lawsuit against STRESS in spring 1972 (which provided much of the information challenging police accounts contained below), multiple eyewitnesses and wounded survivors testified to a consistent pattern of police criminality in almost all of the decoy unit's fatalities. The city of Detroit later settled wrongful death lawsuits in a majority of these undercover decoy cases. The combination of the evidence presented in civil litigation, and the consistently scripted nature of the official police accounts, strongly indicate that most were wrongful deaths involving excessive and unjustifed force, followed by DPD coverups.

Cortez Marcilis (April 24, 1971). Marcilis, a 15-year-old Latino, was shot and killed by Patrolman Ronald Jones around 11:30 p.m. near the Eastown Theater, a rock music venue in Northeast Detroit. Jones and his partner, Ronald Sexton, were in plainclothes and "posing as innocent civilians" because of recent muggings in the area. Cortez Marcilis and an unidentified 16-year-old male allegedly tried to rob the undercover decoy team with a gun. Patrolman Jones claimed that he pulled out his revolver, identified himself as a police officer, and ordered the youth to surrender. Then, Jones alleged, Cortez Marcilis fired two shots at the officers, and then the two boys began to flee. Jones said that he ordered the youth to halt and then fired twice, killing Cortez Marcilis with a bullet in the back of the head. The officers arrested the other juvenile, who was charged with armed robbery. The family of Cortez Marcilis expressed shock and disbelief at these events, saying Cortez had just left his house to walk the friend home, did not own a gun, had not been involved in criminal activity, and was about to graduate from high school. The DPD and the newspapers did not formally attribute this shooting to STRESS, likely because the unit's existence had not been publicly disclosed yet, but the tactics matched those of the undercover decoy operation and the civil lawsuit filed by the Legal Defense Coalition listed Marcilis as the first STRESS homicide. Assuming so, the Latino teenager was the only non-African American killed by a STRESS decoy unit.

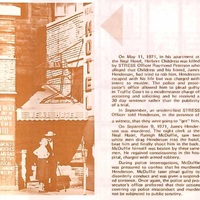

Herbert Childress (May 11, 1971). Childress, a 35-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Raymond Peterson inside a private apartment. The incident began around 1:00 a.m. when, according to Peterson, he was acting as an undercover decoy in a known vice district near downtown and was propositioned by a "homosexual" prostitute/"colored female-male"--"a man attired as a woman." Peterson accompanied the transgender prostitute, whose name was James Henderson, into an apartment and said that he found two other men there in bed together. Peterson claimed that he rejected their sexual advances and tried to leave, and so the three men attacked him. He claimed that one "colored male" [Childress] "was brandishing a raised knife and stated, 'I am going to kill you, you white mother fucker'" and then swung and connected with his head. Peterson then fired twice and killed the purported ringleader and alleged assailant, Herbert Childress. The other two escaped, but a few months later Peterson killed Henderson in a very suspicious incident (see below).

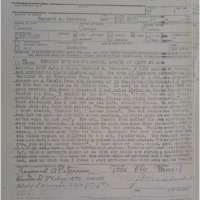

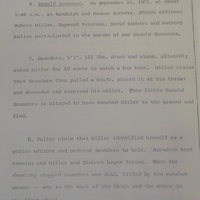

Clarence Manning, Jr. (May 29, 1971). Manning, a 25-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Raymond Peterson acting alongside other white STRESS officers. According to the DPD, Manning and another man, Nathaniel Johnson, tried to rob undercover STRESS officer Michael Worley at gunpoint in the early morning hours. They allegedly kept attacking Patrolman Worley after he identified himself as an officer, and then sought to flee in their car. Worley claimed that he feared for his life and that Manning had attacked him with a bottle while Johnson pointed a gun at him from the car window. Worley and his backup team, including Patrolmen Peterson, Richard Worobec, and Marvin Johnson, fired 18 shots at the fleeing suspects, killing Manning. According to a civil lawsuit filed by Manning's family, Patrolman Worley accosted the deceased man in disguise as a bearded hippie, verbally abused and provoked him, and then shot Manning as he approached. The STRESS backup team immediately opened fire on the unarmed man, striking Manning seven times. In his statement (left), Patrolman Peterson claimed that he shot Clarence Manning because the "colored male" threw a bottle at Worley, and then shot the "thug" again as he lay on the ground because he "got up and raised his right hand toward me." The autopsy report confirmed that the fatal wound came from Raymond Peterson's gun from a distance of less than five inches, indicating an execution rather than self-defense against an armed assailant. Nathaniel Johnson, who remained in the car throughout this encounter, drove away in a panic, not even knowing the assailants were police officers. Johnson was arrested almost immediately and charged with felonious assault but acquitted by an all-Black jury. (A reverend on the jury said he received anonymous phone threats that in the event of a not guilty verdict, "they would burn my church.") In 1975, the city of Detroit paid $180,000 to Clarence Manning's family to settle a wrongful death lawsuit, in acknowledgment that a jury would likely agree that the STRESS officers had used excessive force and lied about the encounter.

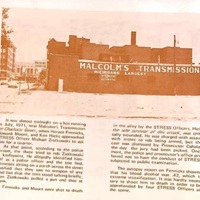

Horace Fennicks and Howard Moore (July 5, 1971). Fennicks, a 28-year-old African American male, and Moore, a 32-year-old African American male, were shot and killed by an all-white STRESS team a little after midnight after they asked undercover decoy officer Michael Ziolkowski for a quarter. Patrolman Ziolkowski claimed that the two men and a third companion, Ken Hicks, then tried to mug him with a knife. He claimed to have identified himself as a police officer and ordered them to halt, but instead they fled. Patrolmen Raymond Peterson and Phillip Kocinski of the STRESS backup team shot and killed Fennicks and Moore, allegedly as they fled while still armed, and claimed to find a knife on Fennicks's body. The autopsy report showed that Fennicks was extremely intoxicated, raising questions about why the STRESS unit did not just apprehend him. Patrolman Ziolowski shot and wounded Hicks, allegedly as he fled, but his stomach wound instead indicated a close-range shooting. The DPD charged Hicks with felonious assault, but a judge dismissed the case for lack of evidence. According to Hicks's testimony in a civil lawsuit against STRESS, when the threesome asked Ziolkowski for a quarter to buy a drink (not knowing the white man was an officer), "he said he didn't have nothing for no n------." Then, when they asked him a second time, Patrolman Zilkowski without provocation "stepped back, pulled a gun, and started shooting." Three other civilian witnesses, including Robert Wren, backed up Hick's testimony that the STRESS officer fired his weapon just because the three men asked him for a quarter. (Police officers threatened Wren's life for agreeing to testify). Fennicks and Moore fled down an alley and died of gunshot wounds in the head and back, fired by the white backup officers. The city of Detroit later paid a $75,000 settlement to the family of Horace Fennicks to settle a wrongful death lawsuit, and the family of Ken Hicks, who had by then died in an unrelated incident, received a $140,000 settlement. For additional documents, including eyewitness testimony, see the STRESS on Trial page.

Harry Taylor (July 6, 1971). Taylor, a 20-year-old African American male, was shot by two white STRESS officers, Patrolmen Donald Lewis and James Bardel, and died eighteen months later from complications due to these injuries. According to the police officers, Taylor and Guilford Pender, also a 20-year-old African American male, attempted to mug Patrolman Lewis, the undercover decoy, with a "sharp object" and then began kicking and beating him after he gave them $5. Lewis then fired his gun, as did backup Patrolman Bardel, sending both of the alleged assailants to the hospital with serious injuries. The officers claimed to find a knife that one of the suspects dropped at the scene. The DPD charged Taylor with armed robbery, but a jury acquitted him. Before he died, in testimony in a civil lawsuit, Harry Taylor said that he and Pender had left a bar around 2:00 a.m. and stepped into an alley to urinate. They were then attacked for no reason by a white man (Patrolman Lewis) who "shot me in the stomach. The bullet spun me around. Then he shot me again." Then the other officer, Patrolman Bardel, began kicking him, called him a "Black n-----," and threatened to kill him. In 1976, the family of Harry Taylor received a $100,000 wrongful death settlement from the city of Detroit, and Guilford Pender, who survived, received $150,000.

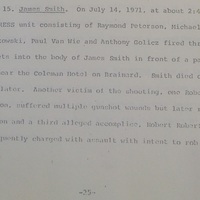

James Smith (July 14, 1971). Smith, a 32-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by a STRESS team that included Patrolmen Paul Van Wie, Raymond Peterson, Michael Ziolkowski, and Anthony Golicz. In the DPD version, Smith and two other African American males accosted Patrolman Van Wie, the undercover decoy, in a narcotics vice district around 2:45 a.m. and invited him to visit an illegal after-hours bar. When Van Wie declined, they allegedly attacked and tried to mug him, with one wielding a knife. Van Wie claimed to have identified himself as a police officer before shooting James Smith as he fled. The STRESS team shot and wounded another suspect, Robert Pearson, and charged him and the third alleged accomplice, Robert Roberts, with armed robbery. According to testimony by the two survivors, Pearson and Roberts, the police account was a complete fabrication. They stated that Patrolman Van Wie precipitated the encounter while pretending to be drunk, and James Smith was not even initially on the scene. Instead, Smith emerged from a nearby hotel and told the group to stop loitering. The STRESS team then began firing, killing James Smith, who in no way had threatened any of them and did not know his alleged accomplices. Smith died of three gunshot wounds one week later.

Louis Ellios, Jr. (September 3, 1971). Ellios, a 38-year-old white male, was shot and killed by STRESS officer Robert Miller around 9:00 p.m. in his own home. The STRESS team responded to a report that an inebriated Ellios was sitting on his porch waving an unloaded shotgun. Ellios had gone upstairs when the plainclothes officers arrived, and as he walked back downstairs still holding the gun, Patrolman Miller blew a hole through his stomach from close range with a shotgun. The officer claimed that Ellios had pointed the shotgun at him. The Labor Defense Fund included Ellios in its civil lawsuit against STRESS and argued that the DPD officers easily could have disarmed the drunk and diminutive (125 pound) man without killing him.

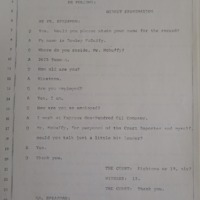

James Henderson (September 9, 1971). Henderson, a 24-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by white STRESS officers Raymond Peterson and James Brown around 2:00 a.m. inside the Neal Hotel. The anti-STRESS movement, led by the Labor Defense Coalition, charged that the two officers murdered Henderson to silence him as an eyewitness to Patrolman Peterson's suspicious killing of Herbert Childress the previous May, when Henderson allegedly had lured the undercover decoy into an apartment for a homosexual liaison (see above). In the September incident, Patrolman Brown claimed that, while acting as a decoy, two men asked if he wanted "a girl" (allegedly soliciting him for prostitution) and then jumped him with a knife and tried to rob him. Patrolman Peterson, the backup, claimed that as he responded to the situation of Henderson holding a knife to Brown's throat, someone inside the hotel yelled 'Police!" Henderson and the other man began to flee, and the STRESS officers cornered them in a room. In Peterson's story, Henderson then threatened the officers by claiming to have a shotgun (none was found, and threatening an armed officer with a nonexistent gun defies logic). Peterson and Brown both stated that they then shot the cornered Henderson through a closed bathroom door (although the bullet wound was in the back) and 'found' the knife. The other man was Rawley McDuffy, the hotel night clerk, whom the STRESS unit arrested as an accomplice to armed robbery, presumably to intimidate him against reporting what he actually saw. The STRESS team claimed that McDuffy yelled "Get out of my way or I will kill you mother fucker" and threated Patrolman Brown with a can of paint. After a judge dismissed this charge as completely unjustified, the prosecutor offered McDuffy a plea deal for disorderly conduct.

In the anti-STRESS lawsuit, the Labor Defense Coalition contended that Patrolmen Peterson and Brown shot James Henderson in the back in a deliberately planned execution. The LDC compiled firsthand evidence that a few weeks before the fatal shooting, a DPD car drove by Henderson's residence and an officer called out, "Bitch, we're going to get you next." A few days before Henderson died, another unidentified STRESS officer informed him that the unit would "get" him soon. The night clerk, Rawley McDuffy, testified that he witnessed two white men (Patrolmen Peterson and Brown) enter the hotel and begin beating James Henderson. When McDuffy tried to intervene, the plainclothes officers beat and threatened him as well. The officers then dragged Henderson into a room, and McDuffy heard one of them yell, "Run, n-----," followed by five or six gunshots. The two officers then returned to beat McDuffy until he was unconscious. McDuffie woke up in the hospital, under arrest as an accomplice, and the STRESS team tried to frame him for the killing. He later courageously testified that he had witnessed a premeditated murder by STRESS officers.

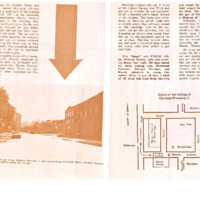

Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell (September 17, 1971). Ricardo Buck, a 15-year-old African American male, and Craig Mitchell, a 16-year-old African American male, were shot and killed by Patrolman Richard Worobec, and possibly other members of his all-white STRESS team, as they fled the scene of a murky encounter. The STRESS unit claimed that Buck and Mitchell had assaulted Patrolman Worobec, the undercover decoy, with a steel rod and stolen his watch before fleeing when he yelled "Halt Police!" Worobec claimed that he then shot both teenagers in the back as they fled in different directions and recovered his watch under Ricardo Buck's body. Multiple teenage eyewitnesses contradicted the police version and insisted that Worobec had instigated the encounter, fired unprovoked at the unarmed youth, planted the watch on Buck's body, and that other STRESS officers fired on Buck as well. There are many inconsistencies in the STRESS unit's account and an almost certain DPD coverup of what really happened, as documented in detail on this section's previous Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell page. The STRESS killings of two unarmed and fleeing teenagers led to a mass protest movement and two civil rights investigations calling for major reforms, which the DPD rejected. The city of Detroit paid $270,000 to settle a wrongful death lawsuit brought by the families of the two boys.

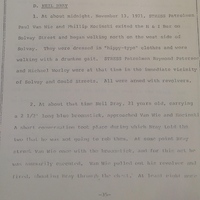

Donald Saunders (September 21, 1971). Saunders, a 39-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Robert Miller, acting as undercover decoy, and possibly another member of his all-white STRESS team. Miller alleged that around 1:45 a.m., Saunders asked him for 20 cents for bus fare and then, when the plainclothes officer said he had no change, pulled a knife to his throat and stole his wallet, then knocked him down and began to run away. Patrolman Miller then claimed that he identified himself as a police officer, ordered Saunders to halt, and then fired several shots when the suspect kept fleeing. Patrolman David Siebert, part of the backup team, also fired shots at Saunders. The forensic evidence contradicted this account and revealed that Saunders had been shot from the front, in the chest from close range, as well as in the hip. (Click here to read an excerpt from Patrolman Miller's testimony and the contradictory evidence provided by the Wayne County Medical Examiner). The anti-STRESS lawsuit labeled the Saunders homicide a collective STRESS "murder" because of the location of the chest wound and also asked how a very inebriated, very small (122 pound) man could have roughed up Patrolman Miller as alleged.

Silas Hudgins (November 12, 1971). Hudgins, a 50-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by STRESS officers Virgil Starkey and James Harris, along with Patrolman Milan Karadandza of the 10th Precinct, when two different units responded to reports of a man wielding a shotgun at 2:14 a.m. at an apartment building on the East Side of Detroit. Starkey and Harris were the first two African American officers credited with a STRESS killing. In the police account, Hudgins threatened other residents of the building and then pointed the gun at the officers, fired one shot, and refused to drop the weapon when so ordered. The three patrolmen hit Hudgins with fatal shots in the chest and abdomen. The DPD emphasized that the officers "had to fire for self-protection" and that the incident had nothing to do with the controversial STRESS decoy operation. This was true, although the tragedy raised different questions about the tendency of police to respond with gunfire to people undergoing mental health crises.

Neil Bray (November 13, 1971). Bray, a 21-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Paul Van Wie, the undercover decoy, and other members of his all-white STRESS unit just before midnight outside of a bar. Van Wie and his partner, Patrolman Phillip Kocinski, were disguised as hippies and pretending to be inebriated when they encountered Neil Bray, with Patrolmen Raymond Peterson and Michael Worley working backup. In the police version, Bray accosted the two decoys with a broom handle, striking Van Wie in the face, and demanded their money. Van Wie claimed that another member of the group Bray was with allegedly threatened them with a sawed-off shotgun, but the police did not recover this at the scene. Van Wie immediately opened fire, striking Bray in the chest. The other three members of the STRESS team promptly began shooting and fired around a dozen rounds all together. Patrolman Peterson claimed to have shot Bray as he fled the scene and "lunged" at him, despite the likelihood that the young man died when Van Wie shot him from point-blank range. Bray suffered six gunshot wounds and was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. Patrolman Van Wie sought treatment for "facial abrasions." In the civil lawsuit, the Legal Defense Coalition acknowledged that Bray struck Patrolman Van Wie with a broomstick but also asked what the undercover "hippies" might have done during the encounter to possibly provoke this escalation. The LDC contended that "for this act, he [Bray] was summarily executed. . . . At no time did the officers attempt to disarm or arrest Neil Bray."

1972: Four Civilian Casualties and One Law Enforcement Victim

The fatality rate of the STRESS unit declined significantly in 1972, especially after the Detroit Police Department implemented reforms to the deadly decoy program following the Rochester Street Massacre in early March, when a STRESS team killed an African American county sheriff's deputy. The anti-STRESS protests by a broad civil rights coalition during spring 1972 undoubtedly saved lives, forcing the DPD to scale back the decoy operation before the warmer summer months when the bulk of police shootings traditionally occurred. The dominant pattern of STRESS decoy-instigated killings marked by excessive force and wrongful death in street patrols, so clearly evident throughout 1971, also gave way to a more diverse set of circumstances in the five homicides attributed to STRESS officers during 1972. Still, the majority of STRESS homicides continued to involve unarmed victims or younger African American males who allegedly, and inexplicably, attacked officers with knives and other weapons, raising suspicious patterns of excessive force and police coverups, especially given the context in which STRESS operated.

Everett Winfrey (February 25, 1972). Winfrey, a 26-year-old African American male, was shot in the chest by white STRESS officer James McCallum and died from his wounds several weeks later. Winfrey allegedly snatched a purse from a 50-year-old woman, who reported the incident to a team of STRESS officers. Patrolman McCallum cornered Winfrey in a parking garage and shot him several times. Winfrey was not armed, and it is not clear why the shooting of a cornered man was justified under DPD regulations that apprehension of a suspect should take place without deadly force when possible. McCallum claimed that the suspect ignored orders to halt and turned around just as he was shot, explaining the bullet wound in the chest. This suspicious police account did not generate the controversy and civil litigation of previous STRESS killings, perhaps because the purse-snatching victim was a civilian and not a decoy officer, but whether the use of force was justified is certainly debatable.

Deputy Henry Henderson (March 9, 1972). Henderson, a 33-year-old African American male and Wayne County Sheriff's Deputy, was killed during an incident that started when a STRESS team ambushed an all-Black group of sheriff's deputies and civilians who were playing poker in an apartment building. The STRESS officers (Patrolmen Virgil Starkey, Ronald Martin, and James Harris) and two other DPD officers (Dennis Shiemke, David Marshall) fired more than 40 shots during the exchange, fatally wounding Henderson and seriously wounding Deputy James Jenkins. Both men were unarmed and trying to surrender when shot. All of the law enforcement officers involved were African American except for Patrolmen Shiemke, who fired the fatal shot that killed Deputy Henderson, and Patrolman Marshall. Despite this, the Wayne County Prosecutor exonerated the two white DPD officers while bringing charges for assault with intent to murder James Jenkins against the three African American STRESS officers. No DPD officer faced charges for the homicide of Henry Henderson. The ambush, dubbed the Rochester Street Massacre, generated massive protests and bitter charges of a DPD coverup and selective prosecution of the Black officers alone. The city of Detroit paid a combined $2.9 million in civil litigation brought by Deputy Jenkins and the widow of Deputy Henderson. For the full account of this incident, visit the Rochester Street Massacre page.

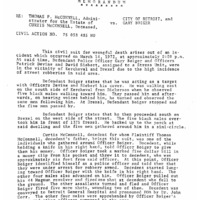

Curtis McConnell (March 14, 1972). McConnell, a 15-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Gary Boiger, acting as undercover decoy, when he allegedly "lunged" at the officer with a knife during a robbery attempt. It was the sixth time that Patrolman Boiger shot and wounded a Black civilian during a decoy operation, but the only fatality. Boiger claimed that a group of five Black youth armed with knives surrounded him on the street at night and and forced him to hand over $5. The decoy officer claimed that after he identified himself as an officer and ordered them to halt, McConnell attacked him--a sequence of events that seems implausible at best. Patrolman Boiger and two backup members of his all-white team, Patrolmen David Siebert and Pat Devine, also shot and wounded two other youth and arrested the surviving four on charges of armed robbery. The Detroit Police Department gave Patrolman Boiger its Distinguished Medal of Valor for his bravery as an undercover decoy, while the Labor Defense Coalition named him as a defendant in its anti-STRESS lawsuit filed one month after the officer killed Curtis McConnell. The NAACP responded to the fatal shooting of another African American teenager by sending a telegram to Mayor Gribbs and DPD Commissioner Nichols demanding the abolition of STRESS and charging that "the wanton policy of this operation, 'Shoot first and ask questions later,' is the brutal attitude of most if not all of its officers."

In 1979, the city of Detroit settled a wrongful death lawsuit brought by Curtis McConnell's father for $190,000. The Law Department advised the settlement because the physical evidence corroborated "the assailants' version of the incident," that Curtis McConnell was "turning to flee when shot as opposed to lunging at Officer Boiger with a knife in his right hand" (right). The Law Department also noted that the DPD had not checked the knife found at the scene for fingerprints. In short, Patrolman Boiger lied when he claimed that McConnell attacked him, the STRESS team probably then planted the knife, and the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office definitely did not conduct an impartial or thorough investigation. The Law Department warned that a jury verdict would be far higher than the proposed settlement because of the strong evidence that Patrolman Boiger "used unjustified deadly force."

Five years after his death, Curtis McConnell's family had published this memorial tribute:

Anthony Oden (November 5, 1972). Oden, an African American man (age unknown), was shot by Patrolman Charles Eggers outside a bar on Woodward Avenue around 11:30 p.m. Eggers alleged that Oden was a so-called "Murphy man" (a fradulent pimp) who asked if the undercover decoy "wanted a girl." When Eggers said yes, Oden allegedly led him a few blocks away and pulled out a revolver, but the gun misfired. Eggers then shot Oden four times. If the incident really happened as Eggers described, it violated a STRESS policy put in place after the May 1971 shooting of Herbert Childress that decoy officers should not proceed alone into prostitution situations. Two weeks after the incident, the Detroit Free Press reported that Oden's wounds were non-fatal, but in a 1974 survey of all STRESS fatalities the newspaper included Oden in the list. Our project has not located any other evidence about Oden in the archives and newspaper databases, and it is not completely clear if his was a fatal or non-fatal shooting. The minimal coverage available (right) mainly highlighted that the DPD had relaunched the STRESS decoy operation with more adequate safeguards, including psychological screening of officers and supervisor approval of target locations, in response to the mass protests that followed the Rochester Street Massacre and fatal shooting of teenager Curtis McConnell the previous March.

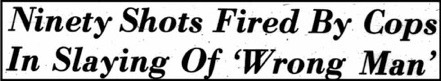

Durwood Foshee (December 8, 1972). Foshee, a 57-year-old African American man, was shot and killed in a hail of bullets inside his own home when a police contingent that included nine plainclothes STRESS officers invaded on a false tip. While Patrolmen James Bennett and Peter Bullach allegedly fired the fatal shots, there were at least 28 police officers from STRESS and non-STRESS units from both the DPD and the city of Highland Park inside or surrounding Foshee's house that night.The incident took place during a massive DPD manhunt for three Black community activists who had wounded several members of a STRESS team in a murky shootout (see this page for a detailed account). DPD officers burst into many private homes without warrants during the month-long manhunt and brutalized many innocent African American citizens. At 2:10 a.m. on December 8, Durwood Foshee awoke to find a large group of armed men without uniforms inside his house, almost certainly even inside his bedroom. The police officers, who did not have a warrant, claimed that they were on the front porch and had knocked and identified themselves as law enforcement before Foshee fired a single shotgun blast out of a window. Then, according to the officers present, they kicked in the door, told Foshee to drop the weapon, and opened fire only after he refused.

The police account of Durwood Foshee's death is almost certainly fabricated, not least because the victim was in his own bedroom when the invading police officers fired ninety shots and killed him instantly. It is not clear whether Foshee had even grabbed his shotgun as alleged. The DPD Homicide Bureau never ran a ballistics test on Foshee's shotgun to see if it had even been fired, and the police offered no forensic evidence that he had, only the accounts of police officers who lied about where he was when he died. The DPD admitted that the raid on Foshee's house had been a "mistake," but the Wayne County Prosecutor exonerated all of the officers involved. In 1976, a jury awarded $1.4 million to the family of Durwood Foshee and agreed with the civil litigants that the 57-year-old man had not resisted or threatened the police officers before they murdered him.

1973: Three Civilian Casualties

The STRESS unit acknowledged shooting and killing three civilians during 1973, its final year of operation, a significant decline from the fourteen civilian fatalities attributed to the approximately 100-officer unit during 1971. Only two of the 1973 homicides involved on-duty STRESS officers, and only one of these took place during a street patrol situation. The most controversial, the killing of Robert Hoyt by off-duty Patrolman Raymond Peterson, the deadliest STRESS officer, resulted in prosecution for murder after his scheme to plant a knife on the victim unraveled. It is clear that the massive civil rights mobilization against STRESS, and the legal and political scrutiny that resulted, had some effect in restraining the unit's violent mission and shoot-first tactics. The protests against STRESS peaked in early 1973, in response to the systematic racial abuses of the DPD's manhunt for three Black community activists, and the anti-STRESS coalition also placed the unit on trial through civil litigation and ultimately achieved its abolition when Coleman Young defeated DPD commissioner John Nichols in the mayoral election that fall.

Gerald Dent (March 3, 1973). Dent, a 36-year-old African American male and an attorney, was shot and killed by STRESS Patrolman Richard Worobec, and also fired upon by two other police officers, when he allegedly "went beserk" and started firing a handgun in a courtroom. Patrolman Worobec, who had been responsible for three fatal STRESS shootings during 1971, was testifying on the witness stand against Dent's clients when the attorney stood up and began firing. Dent's motives are unclear, but an African American police officer who knew Dent reported that he had denounced STRESS earlier that day, charging that "all they do is kill Black people." Dent also reportedly had recently attempted suicide, and in the courtroom he held the gun to his own head before he began firing wildly into the air. Patrolman Worobec and his partner, STRESS officer Roger Brooks, emptied their revolvers as did the bailiff, striking Dent six times in the chest and abdomen. Judge James Del Rio, who ducked for cover, called the incident an avoidable tragedy and observed that Dent had not tried to kill anyone, but instead "he wanted to die." The judge later dismissed the charges against Dent's three defendants, finding that the search of their car by Worobec and his STRESS partner had been illegal.

Robert Hoyt (March 9, 1973). Hoyt, a 24-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Raymond Peterson in an off-duty incident that resulted in prosecution of the STRESS officer for second-degree murder. Peterson, who previously had been directly involved in the fatalities of eight other African American males during STRESS operations, indisputably fabricated his account and attempted to frame the victim. Peterson ultimately was acquited by an overwhelmingly white jury even after admitting under oath that he had lied and planted evidence. The incident began after Hoyt and Peterson allegedly were involved in a "sideswipe" car accident on the freeway. However, friends and relatives contended that STRESS officers had continually harassed Robert Hoyt during the months and weeks before his death, leading to suspicions that what happened was actually a targeted killing by a corrupt cop. Patrolman Peterson, who was driving an unmarked sedan, claimed that Hoyt caused the car accident and then illegally fled the scene. Peterson and his off-duty partner, Gary Prochorow, who somehow was also on the scene in a separate personal car, then chased down the suspect and shot at him several times. Peterson claimed that he pulled Robert Hoyt over and shot him dead when Hoyt appeared to be reaching for a gun and then jumped out of the car and attacked the officer with a knife, slashing his jacket. Hoyt was actually unarmed, and after shooting him, Peterson 'discovered' a six-inch knife at the scene. The killing raised instant suspicions because of Peterson's deadly track record, and the forensic evidence proved that the officer had planted the knife, after an African American scientist in the DPD lab found hairs belonging to Peterson's cat on the handle. The forensic evidence also showed that Patrolman Prochorow had shot Robert Hoyt in the wrist while the victim was driving, and that there was no damage to Hoyt's car indicating a "sideswipe," raising more questions about whether STRESS partners Peterson and Prochorow had just reacted with rage to a fender-bender or had deliberately set out to murder Robert Hoyt. The victim's family insisted that the mild-mannered husband and father of a four-year-old son never carried a knife and was completely innocent. For more on this incident, visit the Raymond Peterson page.

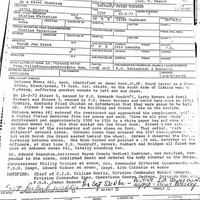

Joan Davis (Oct. 2, 1973). Davis, a 21-year-old African American female, was shot and killed by five STRESS officers after she allegedly robbed a Kentucky Fried Chicken at gunpoint. The officers--Patrolmen Kenneth Woodruff, Larry Nevers, David Siebert, Macon Bridges, and David Dehn--were staking out the restaurant on a tip that Davis, a former employee, was planning the operation. Davis allegedly was armed when she stole around $300, jumped into a getaway car, and then pointed a pistol at the officers who confronted her. The STRESS officers claimed to have chased her on foot and ordered her to halt before she threatened them with the gun. Four of the policemen fired a single shot each, striking her in the chest and killing her instantly; only Patrolman Dehn did not fire. The entire incident was "bizarre," as the Detroit Free Press observed in its coverage, not least in the unusual sequence of multiple police officers responding to an allegedly deadly threat by firing only one time each. Davis, initially identified as "Jewel Gant" in the homicide report (right), was the last person killed by a STRESS unit and the first by an on-duty officer on patrol during 1973. Joan Davis's mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Detroit and received a $275,000 settlement. Her accomplice, who was wounded, testified that Davis was unarmed and that the STRESS officers shot her for no reason.

Non-Fatal STRESS Shootings

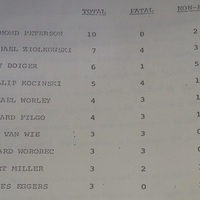

STRESS officers also shot and wounded at least two dozen African American males during the undercover unit's three-year existence, mostly during decoy operations, and probably more. The DPD did not release the actual number of non-fatal STRESS shootings, although the Labor Defense Coalition's lawsuit documented that nine white officers had participated in at least 17 non-fatal incidents through March 1972 (several of these involved the same victim, however).

The interactive map below documents 13 non-fatal STRESS shootings during 1971-1972, overlaid with the 22 STRESS fatalities. Six of these non-fatal shootings happened in the same encounter as a fatal force incident, and seven involved decoy teams. Almost all were Black males in their twenties, except for a 55-year-old man serious wounded during a mental health emergency. Zoom the map to view the cluster of non-fatal and fatal STRESS shootings in the downtown/midtown commercial district. Click the dots to read more about the incident; note that many dots overlap because of the close proximity of decoy operations.

Map of Non-Fatal and Fatal STRESS Shootings, 1971-1973, in Detroit's Racial Geography

- Yellow dots (11) = Non-fatal STRESS shootings (two dots involve two non-fatal shootings each)

- Black dots (14) = Fatal STRESS shootings by undercover decoy units

- Red dots (8) = Fatal STRESS shootings by other STRESS units

13 Identified Victims of STRESS Non-Fatal Shootings

- Dallas Collins (May 3, 1971), an African American male, was shot and wounded by STRESS Patrolman Raymond Peterson during a decoy operation. Collins allegedly tried to mug Peterson, who shot at Collins from the back as he fled. Peterson and other STRESS officers cornered Collins in a building, and Peterson shot and incapacitated him when Collins allegedly, and implausibly, reached for Peterson's gun.

- Kenneth Hicks (July 5, 1971), a 25-year-old African American male, was shot and wounded by a STRESS decoy team in the incident that resulted in the fatal shootings of Horace Fennick and Howard Moore after the group asked undercover officer Michael Ziolkowski for a quarter. Hicks was shot by Patrolman Ziolkowski while fleeing. (Read his testimony in the STRESS trial here).

- Guilford Pender (July 6, 1971), a 20-year-old African American male, was Black, Male, 20) shot and wounded by STRESS decoy team officers in the incident that resulted in the fatal shooting of Harry Taylor. The officers shot Pender and Taylor in an alley outside a bar without provocation and then beat them and arrested them for armed robbery. Pender suffered a disability and won a civil lawsuit.

- Robert Pearson (July 14, 1971), an African American male, was shot multiple times by STRESS officers while "loitering" outside a hotel in the decoy incident that resulted in the fatal shooting of James Smith. Pearson did now know Smith and did not appear to do anything before Patrolman Paul Van Wie shot him.

- James Thomas (Dec. 22, 1971), a 29-year-old African American male, was shot and wounded by STRESS officers Virgil Starkey and James Harris, Black officers part of the STRESS team later charged with attempted murder in the Rochester Street Incident. The officers claimed that Thomas had a gun and aimed it at them.

- Harold Singleton (Jan. 23, 1972), a 26-year-old African American male, was shot and wounded by STRESS Patrolman Charles Eggers six times without provocation after walking away when Eggers, who was undercover, cursed him. The backup team converged and kicked Singleton on the ground. They arrested Singleton for armed robbery for allegedly attacking Eggers with a knife. (Read the Labor Defense Coalition's account of the Singleton shooting here).

- John Simmons and Lonnie Parker (March 6, 1972). Simmons and Parker, both 21-year-old African American males, were shot and wounded by STRESS decoy officer Gary Boiger after they asked him for 50 cents. Boiger then shot Simmons in the chest and shot Parker as he fled. The STRESS backup team also shot Parker and--according to witnesses--kicked and beat him after he fell to the ground wounded, told him to die, and used racist slurs. (Read the Labor Defense Coalition's account of the Simmons and Parker shootings here).

- Eddie Murphy (March 9, 1972), a 24-year-old African American male, was shot by STRESS officer Donald Lewis outside of a bar without cause. His companion James Lawless, a 29-year-old African American male, was pistol-whipped by the STRESS decoy team. Murphy and Lawless were acquitted of attempted robbery after spending five months in jail on excessive bail.

- Deputy James Jenkins and Deputy Henry Duvall (March 19, 1972). Jenkins and Duvall, both 29-year-old African American males and Washtenaw County Sheriff's deputies, were shot by STRESS Patrolmen Virgil Starkey, Ronald Martin, and James Harris during the Rochester Street Incident that also resulted in the homicide of Deputy Harry Henderson. The STRESS officers faced trial for attempted murder of Jenkins but were acquitted. Jenkins received $1.65 million in a civil lawsuit, and Duvall $100,000.

- Willie Petties (August 24, 1972), a 55-year-old African American male, was shot and seriously wounded by four STRESS officers responding to a call of a man brandishing a gun. Petties was experiencing a mental health crisis and fired two shots at the police, who returned fire and hit him with four gunshots.

- Ronald Short (Sept. 1, 1972), a 20-year-old African American male, was shot and wounded by STRESS Patrolman Kenneth Woodruff during an alleged home burglary. Woodruff shot Ronald Short in the leg as he fled.

STRESS Officers Killed in the Line of Duty

Three STRESS officers died of gunshot wounds in the line of duty during the three-year duration of the operation. None were decoy unit officers (no decoy officers were even wounded during their deadly and violent operations). There was a massive racial difference in how the Detroit Police Department responded to these fatalities, ranging from an enormous month-long manhunt to capture the Black community activists held responsible for the death of white Patrolman Robert Bradford to a perfunctory investigation and no mobilization after the death of African American Patrolman Frederick Hunter. This was part of a broader pattern of neglect after the deaths of Black officers, especially those involved in policing narcotics and vice districts, raising questions about the links between DPD corruption in the narcotics trade and the unsolved murders of several African American law enforcement officers.

Patrolman Frederick Hunter, Jr. (August 26, 1971). Hunter, a 22-year-old African American male and rookie policeman, was shot and killed by an unidentified suspect after a foot chase in a 10th precinct neighborhood that was a major target of STRESS decoy operations and narcotics enforcement. According to the police report, Hunter and his partner had stopped to investigate a group that was passing around a gun outside of a known "dope house" when the suspect fled. Hunter had run down an alley, and there were apparently no other witnesses to the actual shooting. The DPD quickly arrested a 21-year-old prostitute for the murder and also detained her 22-year-old 'boyfriend,' but released both for lack of evidence. The Homicide Bureau then issued a warrant for arrest of a 19-year-old man who had recently escaped from prison and was not part of the group standing on the corner targeted in the initial stop, alleging that this individual had been nearby and just happened to decide to shoot Patrolman Hunter as he pursued the fleeing prostitute. This case was dimissed, and the DPD never solved the murder of Patrolman Frederick Hunter, or even seemed to try very hard. (Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols did attend his funeral, along with hundreds of police officers). Given the extensive level of DPD corruption in narcotics markets and the allegations of STRESS narcotics corruption in the Rochester Street Massacre and beyond, the unsolved murder of Patrolman Frederick Hunter is suspicious and raises questions that can probably never be answered.

Sergeant Gerald Riley (December 8, 1972). Riley, a 39-year-old white male, was off duty and in plainclothes when he attempted to stop a bank robbery while in line as a customer and was shot and killed by two suspects. He was a ten-year veteran of the DPD and a supervising officer in the STRESS unit. The DPD Homicide Bureau conducted a very thorough investigation and arrested the two bank robbers, who eventually pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. The case received massive media attention and personal involvement by the mayor and police commissioner, in stark contrast to the unsolved and quickly forgotten murder of STRESS Patrolman Frederick Hunter a year earlier.

Patrolman Robert Bradford (December 27, 1972). Bradford, a 25-year-old white male, was shot and killed during a STRESS stakeout of a house presumed to be occupied by two Black anti-narcotics activists who had previously exchanged gunfire with a STRESS team in a murky encounter. Bradford was participating in a massive police manhunt for the three suspects and died in an exchange of gunfire with one or more of them as they fled the house. The DPD then dramatically escalated the manhunt to avenge the death of Patrolman Bradford. Two of the suspects were later shot and killed by police officers in Atlanta, while the third was arrested in Detroit and charged with murder but acquited. Visit the "Manhunt" page for more on this incident.

In addition to the "Detroit Under Fire" team, Zev Miklethun contributed research for this page.

Sources

From the Ground Up, "Detroit Under STRESS," 1973, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

"Complaint of the Plaintiffs," April 1972, Labor Defense Coalition, et. al, v. Roman Gribbs, et. al, Box 5, Folder 26, Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Howard Kohn, "Terror In the Streets: Detroit's Super Cops," Ramparts (Dec. 1973), 38-41, 55

E. A. Batchelor and Robert M. Pavich, "The STRESS Shootings: Who and How," Detroit News, Sept. 22, 1971

Michael Graham, "STRESS Decoy Defends His Violent Role," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 19, 1971

Mark Binelli, "The Fire Last Time," The New Republic (April 6, 2017)

Detroit Free Press, Feb. 18, 1974 (list of STRESS fatalities)

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Interview with Joe Swickard, November 17, 2019, Ann Arbor MI, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_cfhfc0bk/145739741

Additional sources for individual incidents

Marcilis: Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1971, Detroit News, April 26, 1971

Manning and Johnson: Detroit Free Press, Dec. 9, Dec. 18, 1971

Fennicks and Moore: Detroit Free Press, July 7, 1971, May 13, 1972, Detroit News, March 25, 1976

Taylor: Detroit Free Press, July 7, 1971, Michigan Chronicle, May 13, 1972, Detroit News, March 25, 1976

Henderson: Michigan Chronicle, May 6, 1972

Hudgins: Detroit News, Nov. 12, 1971

Bray: Detroit Free Press, Nov. 15, 1971

Winfrey: Detroit Free Press, Feb. 26, 1972, Detroit News, Feb. 26, March 15, 1972

McConnell: Detroit Free Press, March 15-16, 1972, July 15, 1973, May 29, 1977

Oden: Detroit Free Press, Nov. 19, 1972

Foshee: Michigan Chronicle, Jan. 13, 20, 1973, Dec. 18, 1976, Detroit Free Press, Dec. 9, 1972, Dec. 10, 1976

Dent: Detroit News, April 4-5, 1973; Michigan Chronicle, April 14, 1973

Davis: Detroit Free Press, Oct. 3, 1973

Hoyt: Michigan Chronicle, March 24, 1973, March 2, 1974

Hunter: Detroit Free Press, August 27, 29, 31, 1971, February 7, 1974; Michigan Chronicle, Sept. 11, 1971

Riley: Detroit Free Press, Dec. 9, 1972, Feb. 1, 1973