State of Emergency Committee

The fatal shootings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, two African American teenagers killed by white DPD officers in the STRESS unit, produced an outpouring of protests from a broad cross-section of Black Detroit. Radical activists immediately formed the State of Emergency Committee to coordinate public demonstrations and demanded not only the prosecution of the STRESS officers but also the abolition of the decoy operation. Mainstream civil rights organizations also joined the coalition, which forced the Detroit Police Department and the city government to mount an aggressive defense of STRESS, resulting in exposure of and public debate regarding its methods and philosophy. This controversy led to separate investigations by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and additional calls to end the decoy operation and adopt stricter use of force controls, but the DPD refused to implement their recommended reforms.

The Anti-STRESS Coalition

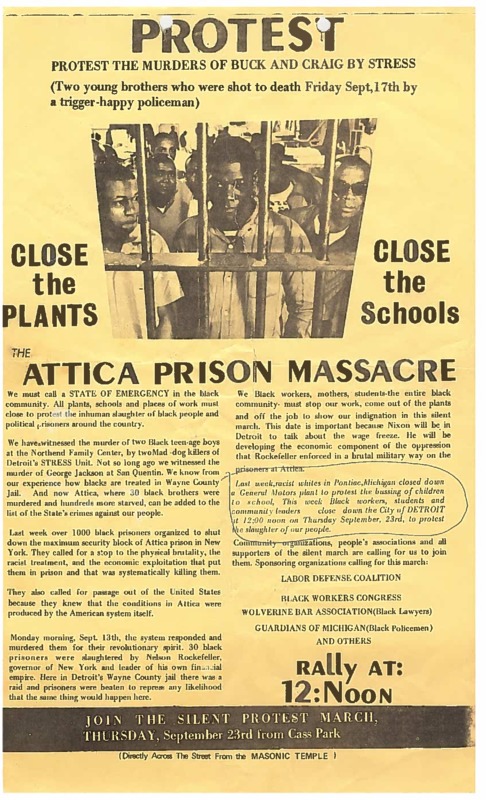

The Labor Defense Coalition (LDC), a recently formed group led by radical attorneys Kenneth Cockrel and Justin Ravitz, took the lead role in organizing the State of Emergency Committee. Cockrel was a prominent Black Power activist who had successfully represented the Republic of New Africa defendants in the New Bethel Incident and, along with Ravitz (whose roots were in the white New Left), had just filed a class-action lawsuit arguing that the conditions of the Wayne County Jail were unconstitutional and that the Black and poor people held inside were political prisoners of a racist society. (For more on this lawsuit, see our project's separate report). In its mission statement, the LDC pledged to "promote the rights of oppressed minorities and poor persons and to combat acts of institutionalized oppression throughout all arms of the administration of criminal justice." The Labor Defense Coalition sought to organize a grassroots anti-STRESS movement in Detroit as part of a broader nationwide mobilization against the racist criminal justice system, placing the police murders of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell alongside the Wayne County Jail litigation, the recent murder of Black Power activist George Jackson in a California prison, and the violent crushing of the Attica Prison Uprising only a week earlier (see flyer at right).

Seventy-five African American community leaders came together to form the State of Emergency Committee on the Sunday after the fatal shootings. The coalition included black nationalist groups such as the Congress of Black Workers and Republic of New Africa, as well as civil rights and labor organizations from the liberal establishment, most notably the leaders of the Detroit chapters of the NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the United Auto Workers. At a press conference three days after the shootings, Kenneth Cockrel and other members of the coalition called for a mass protest march on Thursday, September 23, accompanied by a boycott of the automobile factories and public schools. Cockrel, sitting beside Ricardo Buck's mother Luella, demanded the abolition of STRESS and the removal of Mayor Roman Gribbs for his role in promoting police repression and murder. The Guardians of Michigan, a civil rights organization for Black police officers, also joined the State of Emergency Committee and pledged to provide protection for the marchers. Thomas Moss, the president of the Guardians, labeled STRESS "a form of genocide" designed "for the continued killing of blacks" and contended that Worobec and his unit would have been prosecuted for murder if what they did to Buck and Mitchell had happened in a white suburban neighborhood.

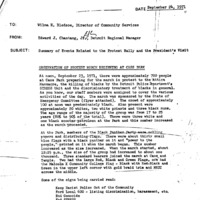

The Detroit Police Department and other law enforcement agencies illegally kept the State of Emergency Committee under surveillance during the planning for the September 23 protest march. The Cockrel papers at Wayne State's Reuther Library include a detailed memorandum about the group's activities based on the combined surveillance of the DPD's Criminal Intelligence Bureau, the Michigan State Police's Special Investigation Unit, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation's COINTELPRO operation (the memo cannot be reproduced under privacy restrictions). This was just one episode in the DPD's systematic, unconstitutional, multiyear surveillance of Kenneth Cockrel and his allies in Detroit's anti-police brutality movement and other radical political causes. DPD officers simultaneously conducted extralegal "surveillance and harassment" of the North End Family Center, the Black community organization that had hosted a smaller-scale protest the evening of the fatal shootings of Buck and Mitchell, and of potential witnesses among Black youth in that neighborhood.

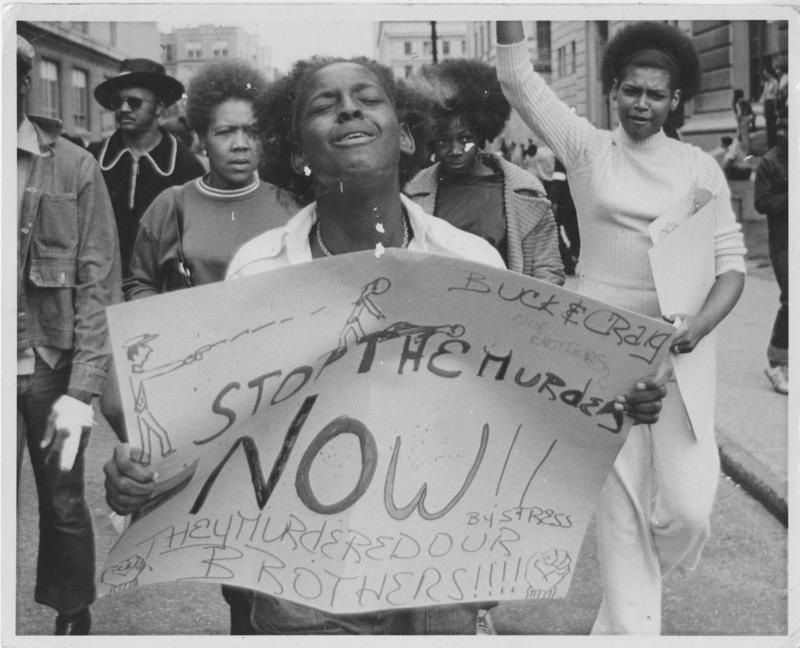

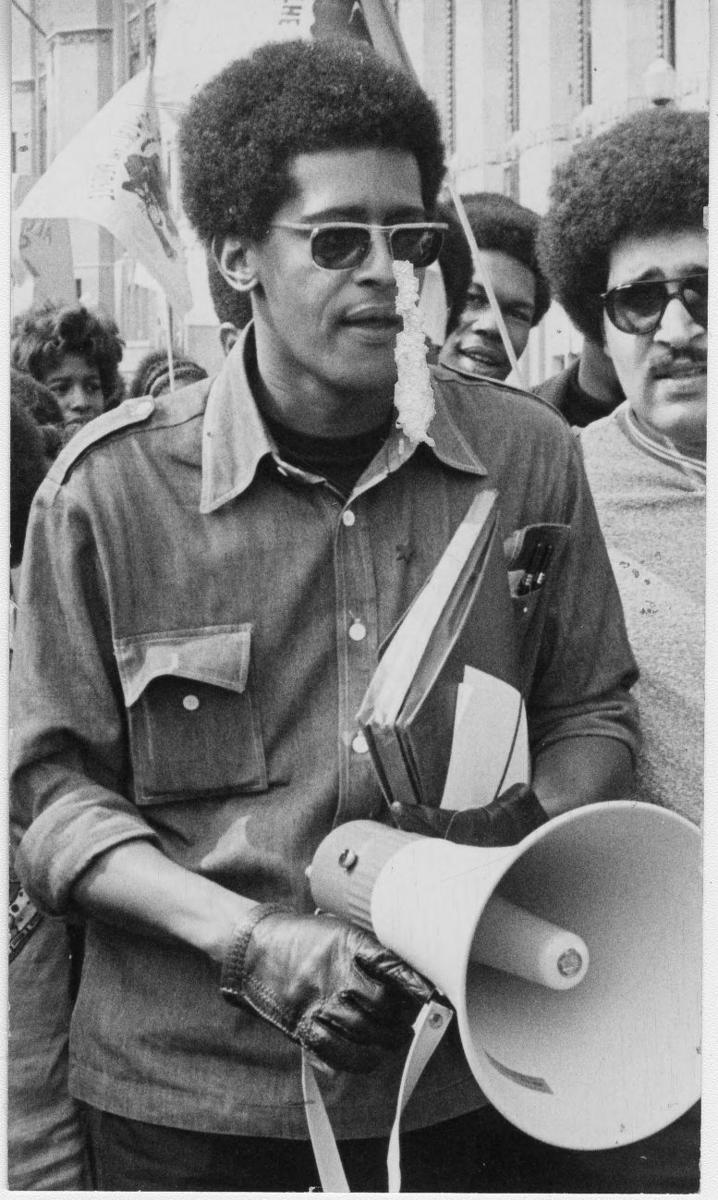

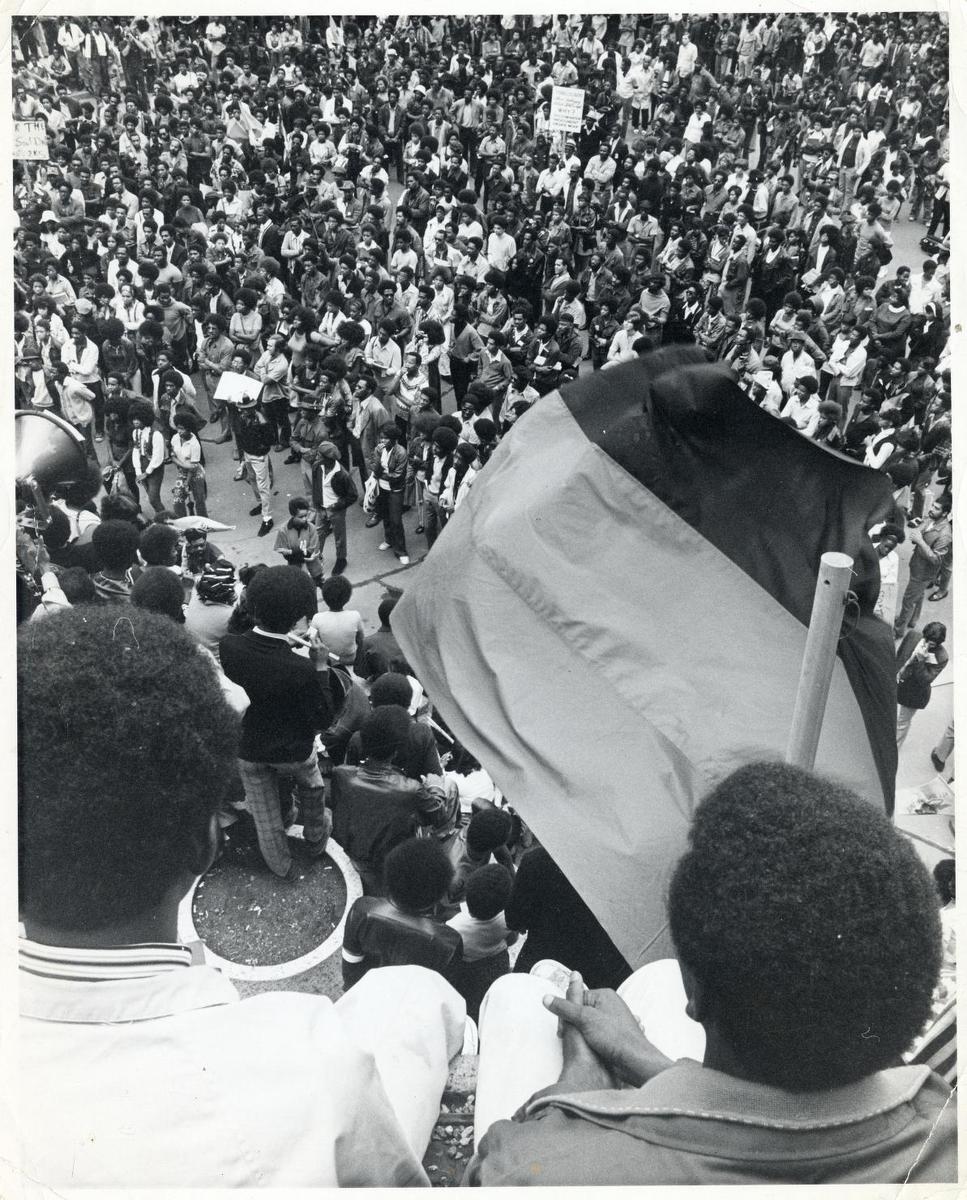

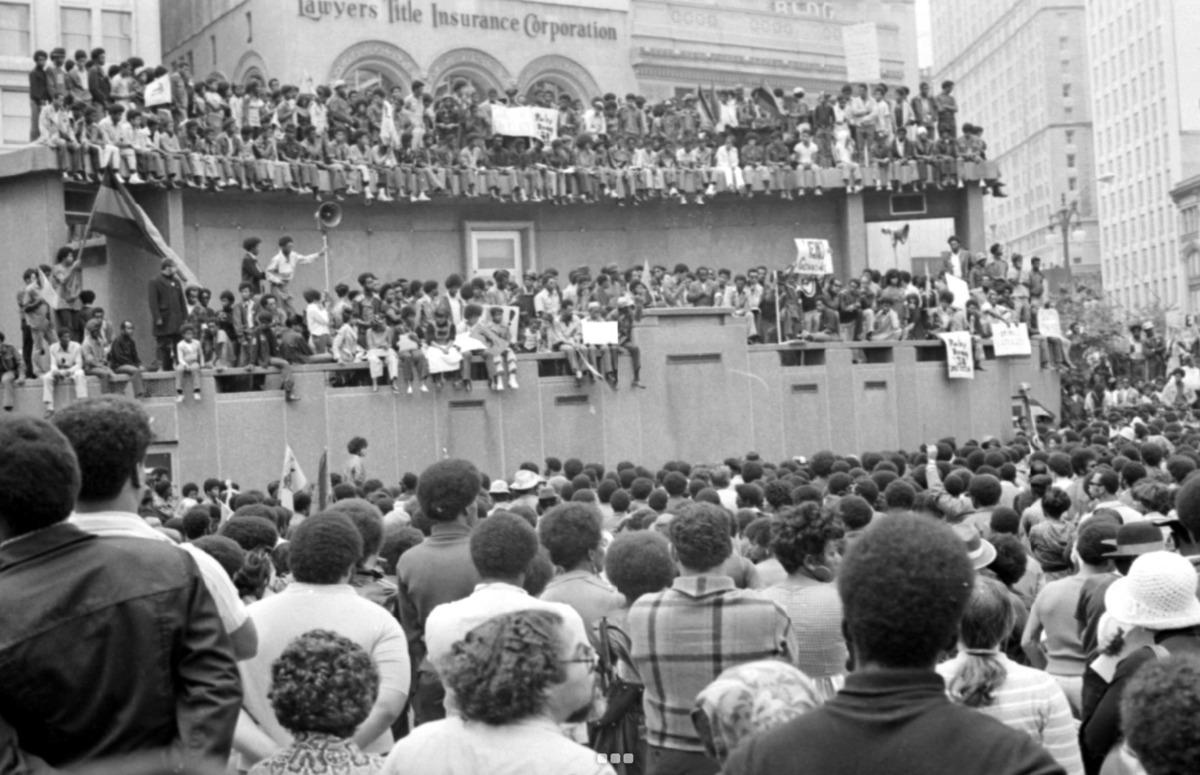

At least 5,000 protesters took part in the State of Emergency Committee march and rally. The group gathered at the Masonic Temple for a mile-long march to Kennedy Square in downtown Detroit on the afternoon of Thursday, September 23. A majority of the participants were young African Americans, including many high schoolers and college students who heeded the State of Emergency Committee's calls for a mass boycott. A small number of white radicals also joined the overwhelmingly African American crowd. Many marchers carried signs with slogans such as "Keep Racist Police Out of the Community," "End Genocide," "End STRESS," and "Buck and Craig-Who's Next?" Off-duty Black police officers from the Guardians served as marshals. The Detroit Police Department and the mainstream news media expressed surprise that the "tightly disciplined" marchers were orderly and nonviolent.

The State of Emergency Committee's advance materials labeled STRESS policemen "Mad-dog killers" and called for the Black community to rise up "to protest the inhuman slaughter of black people and political prisoners around the country." Along the route, the marchers stopped at the Wayne County Jail to express solidarity with the inmates--most of whom were poor Black men who could not afford bail and had not been convicted--and their class-action lawsuit. The plaintiffs responded with an open letter, read to extensive cheers at the Kennedy Square rally, denouncing STRESS as a squad of "hired killers" and directly connecting the murders of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell to the "genocide of Black people" during the Attica Uprising.

The rally itself combined radical critiques of the racist criminal justice system with frequent calls for a "united front" among civil rights, black power, and labor groups. Two NAACP leaders spoke at the rally, along with several prominent Black ministers, the head of the Guardians, and representatives from more radical groups. Louella Buck and Sarah Mitchell, the mothers of Ricardo and Craig, also addressed the crowd and thanked the community for the support and solidarity shown toward their sons. Kenneth Cockrel of the Labor Defense Coalition praised the broad-based coalition for bridging their philosophical and strategic differences and called for the State of Emergency Committee to become a force for unity in the Black community to "combat repression in whatever form it takes, with whatever necessary programs." He ended with a promise that "STRESS will be abolished."

The gallery below contains photographs of the State of Emergency Committee protest march from the Fifth Estate, a radical underground newspaper in Detroit, and the Detroit News.

The DPD's Defense of STRESS and the Deterrent of Deadly Force

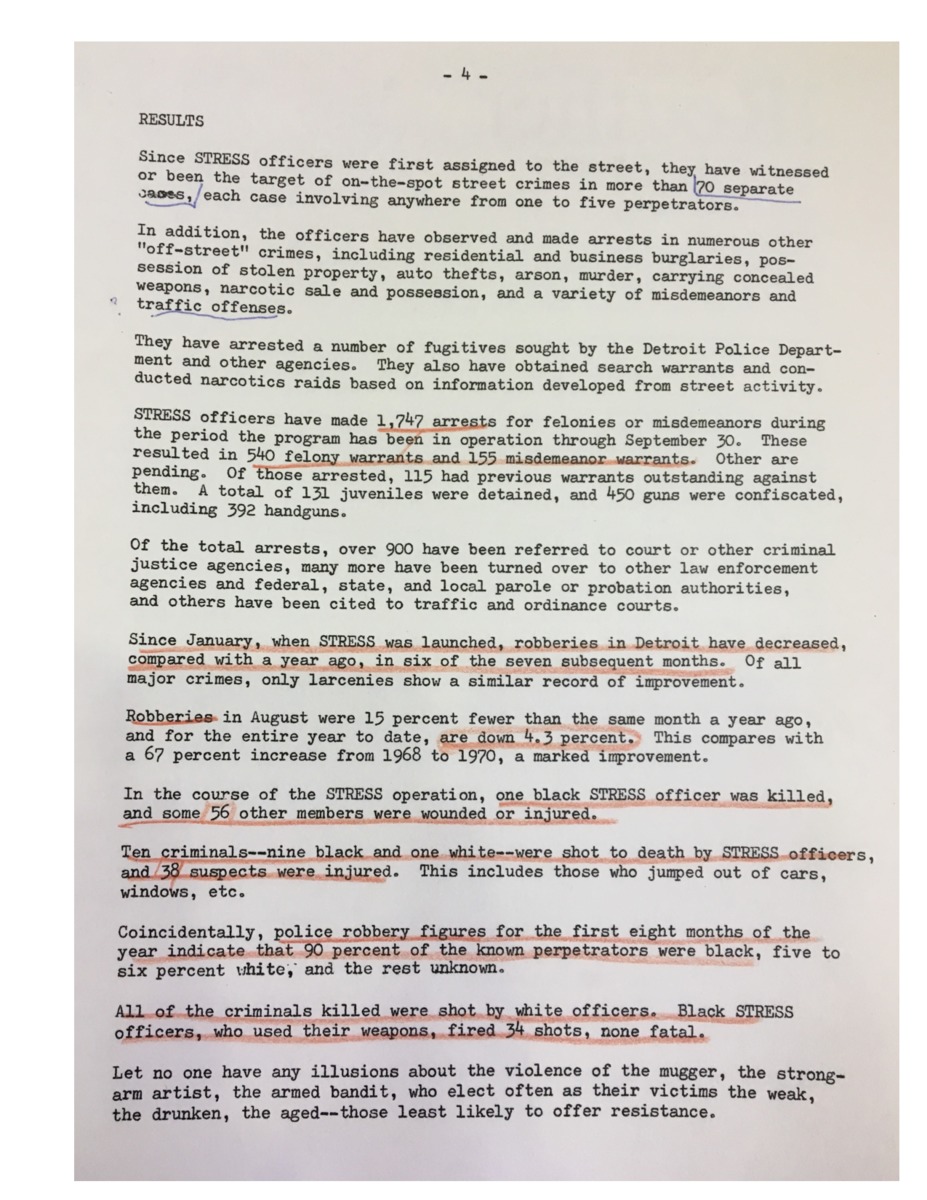

The protest organized by the State of Emergency Committee, and especially the presence of respected mainstream groups such as the NAACP in its coalition, forced the city government and the Detroit Police Department to defend the decoy operation publicly for the first time. The controversy also inspired the mainstream newspapers to dig into the STRESS operation and reveal that officers in the unit had killed ten people, all but one African American males, in a little more than four months.

On September 22, the day before the State of Emergency Committee protest, DPD Commissioner John Nichols and Mayor Roman Gribbs spoke out in aggressive defense of the STRESS initiative. Both men argued that STRESS sought to protect African American citizens, "the principal victims of crime." Gribbs also met privately with a North End community delegation that asked the mayor to remove STRESS from their neighborhood pending the investigation of Richard Worobec, the admitted shooter. Gribbs declined and further denied their charges that the unit deployed with a "shoot-to-kill" policy. Commissioner Nichols also rejected accusations that STRESS was a genocidal operation and that the DPD had declared "open season on black people," while insisting that the police had not "surrendered the streets" to muggers and robbers. STRESS commander James Bannon even claimed that police officers had a binding obligation under state law to fire on fleeing muggers, an implausible and even indefensible interpretation of the legal code that only gave law enforcement the discretionary authority to do so.

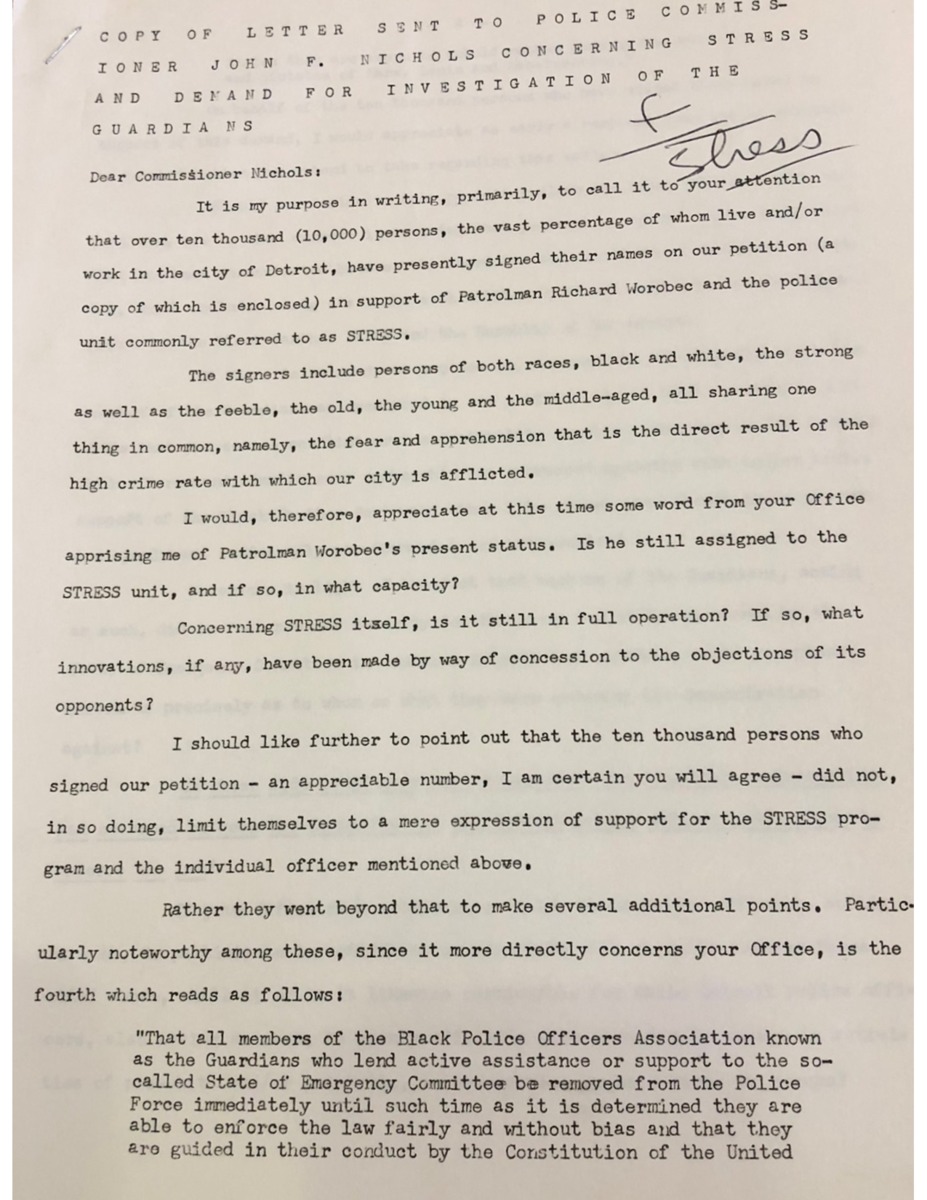

The Detroit City Council, led by white liberal Mel Ravitz, expressed support for the concept of STRESS but also asked Commissioner Nichols to prepare a report explaining the unit's procedures and the selection and training criteria for its officers. The police commissioner appeared before the city council on October 4 at a meeting also scheduled to allow public input on STRESS. More than 150 African Americans crowded into the auditorium, including Ken Cockrel of the State of Emergency Committee accompanied by Louella Buck and Sarah Mitchell, the mothers of the deceased youth. But after Nichols's presentation, the city council abruptly canceled the public hearing, causing deep anger and recriminations among the overwhelmingly Black crowd and fueling charges that the politicians were afraid to listen to the voice of the community and the families of the victims. A smaller group of white residents also attended under the auspices of Breakthrough, a far-right organization that presented a petition signed by around 10,000 people that commended Patrolman Worobec "for the killing of two criminal hoodlums" and demanded the continuation of STRESS and its authorization to shoot fleeing suspects (below gallery, right).

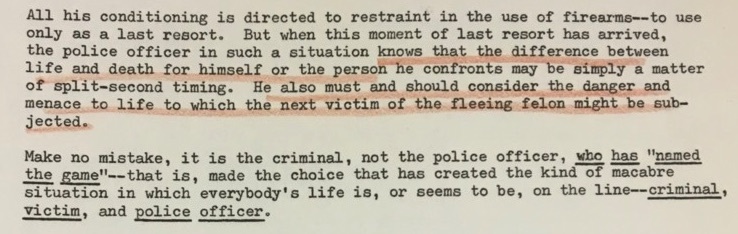

Commissioner Nichols defended Patrolman Worobec's use of deadly force against two unarmed Black teenagers in his public remarks to the city council and also submitted a nine-page report on the STRESS unit's history, operations procedures, and purported effectiveness (reproduced in full below). The first section of the report outlined the origins of the undercover operation and claimed that the DPD had developed rigorous screening and training policies for its volunteer officers (this was strongly disputed by subsequent civil rights investigations, covered below). Nichols then presented data purporting to show that STRESS had reduced the robbery rate through its aggressive methods, using unreliable statistics in an unscientific manner, as detailed on a previous page. The report also acknowledged for the first time that white STRESS officers had killed 10 people thus far in 1971, all but one African American, but Nichols portrayed this as logical based on the assertion that 90 percent of robbery perpetrators in the city were Black. The STRESS report then summarized the use of force policies in state law and the DPD manual, giving police officers the discretionary authority to use force to prevent the escape of a "fleeing felon," but also requiring them to make the arrest "by peaceable means whenever possible."

The DPD report explicitly justified the deployment of undercover decoy officers, and the STRESS concept of controlling the streets through an omnipresent threat of deadly force against unsuspecting muggers, as the most effective deterrent to ensure that criminals would either reconsider their actions or be incapacitated and unable to commit any additional felonies. In the final section, Nichols made the conservative law-and-order argument that the criminal justice system too often did not punish offenders and that muggers in particular faced little deterrent when they targeted vulnerable people. The commissioner portrayed the STRESS decoy operation as the antidote, allowing undercover police officers to ensure that the perpetrators ended up either imprisoned or dead. In summation, Nichols emphasized that the muggers, not the law enforcement officers, had chosen the "game" to be played by making the mistake of trying to rob an undercover decoy and that fatal force was justified to protect the community--and the next potential victim--from the "menace to life" represented by street crime.

Read the full STRESS report presented by Commissioner Nichols on Oct. 4, 1971, in the gallery below.

The Divided Black Community and Demands for Reform

The STRESS report presented to the city council by Commissioner Nichols also asserted that the Sept. 23 protest organized by the State of Emergency Committee did not represent majority sentiment among African Americans in Detroit (above, second from right). As evidence, the police commissioner supplied a breakdown that Black residents had written 19 of the 138 pro-STRESS letters sent to the DPD in the ten days after the shooting deaths of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell. Such correspondence was not, of course, a representative sample of African American public opinion, and throughout the early 1970s the DPD hierarchy consistently defended STRESS by claiming that most African American citizens supported the program and the broader war on street crime, but their quiet voices were drowned out by the radical activists. This argument sought to manipulate Black public opinion for the DPD's own political agenda and was often disingenous and even outright dishonest, as law enforcement officials routinely highlighted African American support for get-tough crime control programs while refusing to acknowledge their critiques of police brutality and pressure for police reform. At the same time, it was also true that there was significant support for the war on street crime among African American residents (especially the elderly) and mainstream civil rights organizations, which led to considerable support for STRESS in its initial phases, as previously detailed. At the most basic level, a large majority of African American residents wanted the police department to protect them from street crime without rampant brutality, without the use of deadly force against either innocent people or Black youth suspected of relatively low-level offenses, and through the deployment of Black police officers in their neighborhoods.

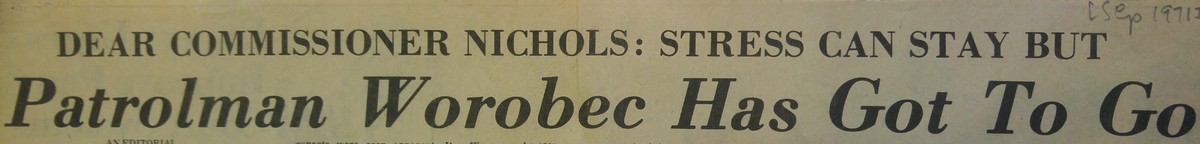

The fatal shooting of two unarmed teenage boys in September 1971 scrambled this political equation and caused a number of mainstream African American organizations in Detroit to demand major reforms of the decoy operation as a condition for their continued support. The Michigan Chronicle, in an editorial titled "STRESS Can Stay but Patrolman Worobec Has Got to Go," praised the undercover operation as a promise of relief for Black inner-city residents who were afraid to walk the streets because of the "onslaught of crime." The African American newspaper insisted that every "law-abiding citizen in this city" supported the concept of STRESS (which was clearly an overstatement) but then argued that the unit's operations had been deeply flawed, in particular the frequent use of deadly force against fleeing suspects who were almost never armed with guns and in no way threatened the lives of the officers who had killed them. The editorial also criticized the DPD's screening policies for STRESS officers who were violent and racially prejudiced, singling out Patrolman Richard Worobec as an obvious example because of his role in the New Bethel Incident and documented "bitterness" toward black activists. The editorial concluded by calling for better screening and training of STRESS decoy officers and reforms of the DPD's use of force practices in order to end "these shoot-to-kill incidents that could be avoided."

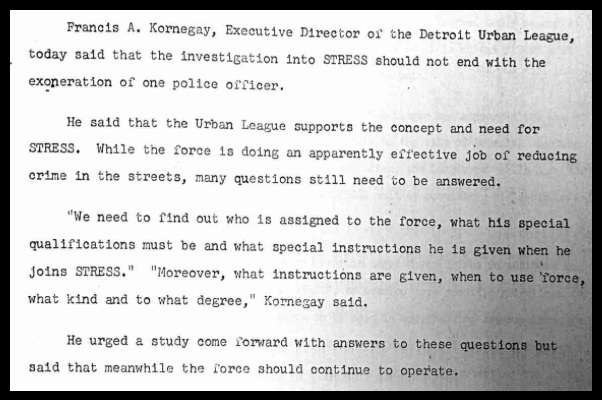

The Detroit Urban League, the city's most moderate and pro-police civil rights organization, also emphasized its support of STRESS as part of its longstanding calls for a tougher war on street crime. Unlike the NAACP, whose leadership endorsed the State of Emergency Committee's protest, DUL executive director Francis Kornegay praised STRESS for fighting an effective war on street crime but also stated that mugging was not a severe enough offense for two teenagers to lose their lives. The DUL joined the Michigan Chronicle in asking for an investigation into the STRESS unit and urged the DPD to improve its screening and training procedures for undercover officers and reevaluate its use of force policies. A number of community leaders from African American neighborhood associations took a similar position, stating that on the whole STRESS was necessary to do something about the scourge of street crime but also criticizing the DPD's permissive use of force policies. Many singled out Patrolman Richard Worobec for condemnation for the killing of two teenagers who were running away and posed no immediate threat.

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission conducted a survey of African American residents of the East Side of Detroit in the aftermath of the Buck and Mitchell shootings and found that a two-thirds majority supported the position of continuing STRESS if the DPD instituted reforms. One-fifth advocated elimination of the unit and 12 percent wanted it retained in its current form. The majority position occupied the middle ground between the DPD's inaccurate claims that most Black citizens of Detroit endorsed STRESS as currently constituted and the State of Emergency Committee's call for abolition of the unit. Black residents advocated changes to the screening and training procedures and the use of force policies, but most of all they demanded that every STRESS team have a majority of African American police officers. At the time, more than 90 percent of STRESS officers were white, which raised questions about the unit's real mission given that a decoy operation designed to protect Black crime victims, as the DPD claimed, would logically deploy African American officers in undercover roles.

Civil Rights Investigations of STRESS

The fatal shootings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, combined with the mass protest by the State of Energency Committee, led to two major civil rights investigations by city and state agencies that called for fundamental reforms of the STRESS operation. The DPD opposed almost all of them.

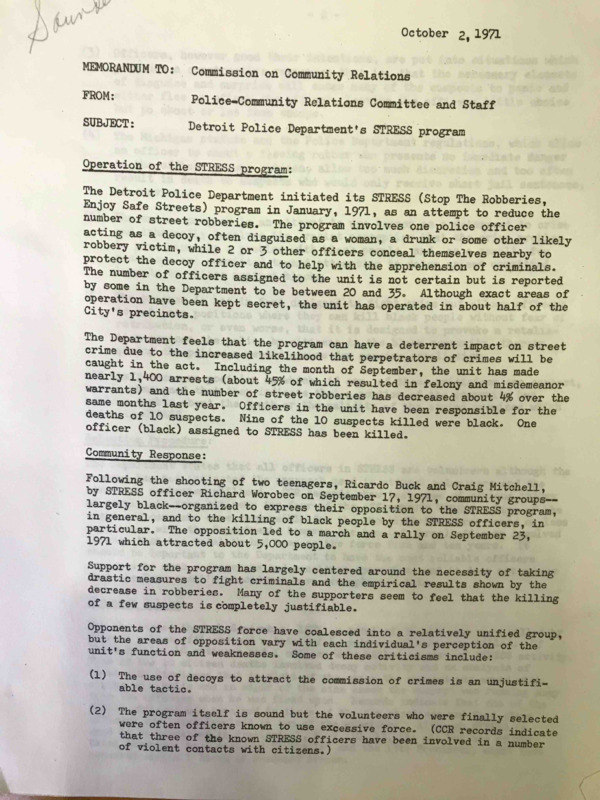

Detroit Commission on Community Relations. In early October, the Police-Community Relations Committee of the DCCR produced an internal, non-public report (gallery below, left) designed to convince the police department and mayor to implement revisions that would make the STRESS operation less deadly and more likely to maintain support from Black residents. The DCCR investigation questioned the DPD's claims of a robust screening process for the officers who volunteered and uncovered evidence that at least four of the white STRESS officers had multiple brutality complaints in their files. The DCCR also found that most of the first ten fatal shootings had been in the commercial corridors along Woodward Avenue and that there was a consistent pattern of suspects running away when shot in the back allegedly armed with either knives or pipes, but not guns (this pattern was suspicious and raised questions of whether STRESS officers planted weapons after using fatal force, as explored on the next page).

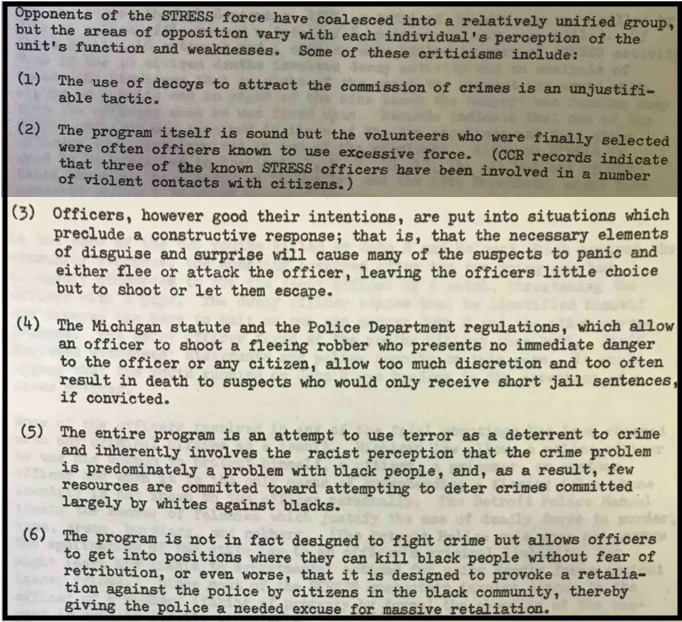

The DCCR report also summarized the positions of the anti-STRESS movement, based on its staff's extensive contacts with civil rights organizations and Black community organizations. The DCCR did not endorse this list (right), but warned the city government and police department that a sizable portion of the public--meaning African American residents and organizations--did not believe the official line on STRESS's agenda and operations. The charges included:

- STRESS decoys were an illegal entrapment tactic

- STRESS volunteers included violent and racist police officers

- The undercover operation was designed to shock surprise and panic suspects into fleeing, justifying homicide

- State laws and DPD policies allowed deadly force for minor offenses, redefined as felony assault

- STRESS was a racist terror operation aimed at Black neighborhoods alone

- STRESS was not a crime control program but rather part of the DPD's broader political repression of the Black community

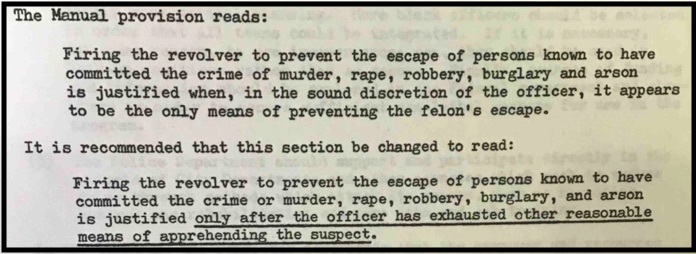

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations report argued that the use of force against fleeing suspects involved in relatively minor property crimes stretched the outer limits of the discretionary authority of police officers under state law and the DPD regulations manual. In sum, STRESS allowed police officers to execute suspects in the street for alleged crimes that often would bring a short jail sentence at most. As a proposed reform, the DCCR advocated that police officers not be empowered to fire their weapons unless their lives were in danger and/or the fleeing suspect "has caused some personal injury to the victim." The report also proposed that since juveniles committed a significant percentage of robberies and larcenies, the DPD should formally restrict officers from "the shooting of perpetrators of minor street crimes that do not result in personal injures" (note that Richard Worobec suffered no injuries during the alleged assault used to justify killing two teenagers). And the DCCR also recommended that the DPD revise its manual to remove the "sound discretion of the officer" as the use of force standard for fleeing felons, to stipulate that deadly force was permissible "only after the officer has exhausted other reasonable means of apprehending the suspect." (The DPD refused to consider these proposals, and it is important to emphasize that curbing street crime through the threat and use of deadly force was explicit to its justification of the STRESS program, and therefore a deliberate design and not a flaw in implementation).

The DCCR report concluded with a series of additional recommendations:

- Suspension of STRESS until the DPD made "drastic changes" to regain the trust of "the total community" (meaning the Black community)

- A "fundamentally restructured" selection process that barred police officers with a track record of using force against civilians and police brutality complaints

- Use of "non-lethal weapons" to apprehend fleeing suspects without gunfire

- Recruitment of Black officers so that all STRESS units were integrated

- A shift from militarized undercover operations toward "community policing" through the Beat Command approach, alongside community patrols involving citizen groups and volunteers

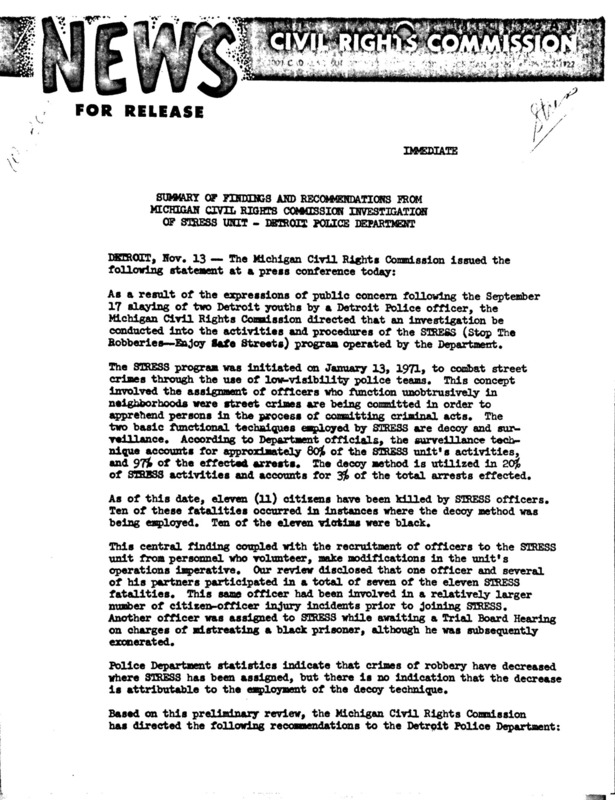

Michigan Civil Rights Commission. The MCRC, a state agency, launched a two-month investigation of STRESS in response to the community protests over the deaths of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell. The detailed inquiry included an interview with James Bannon, the architect of the STRESS operation, and received access to internal DPD records on use of force incidents and brutality complaints against STRESS officers, on the condition that individuals not be identified. (The full report, confidential at the time, is in the gallery below).

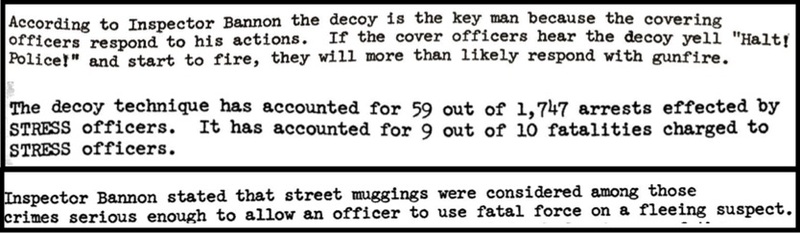

The MCRC's report focused on the decoy operation and demonstrated that the technique had resulted in 90 percent of the deadly force incidents by STRESS officers but only 3 percent of the arrests made by the unit. This raised doubts about the DPD's claims that the undercover decoy operation was an effective crime deterrent, and the inquiry also confirmed suspicions that the STRESS decoy teams deployed with a shoot-first mentality. The MCRC's findings revealed that the 8 black officers in STRESS had killed no suspects and that 9 of the 10 civilians killed by white officers were African American, almost always while fleeing, and many in circumstances the investigators considered to be excessive use of force.

In its most striking finding, the MCRC investigation revealed that a single white officer, Patrolman Raymond Peterson, had been involved in the fatal shootings of 7 civilians in decoy operations. Peterson also had an extensive priot record of using force against civilians, with at least 21 incidents that had been documented, and several brutality complaints against him had been sustained. (For more, visit the Raymond Peterson page). For the MCRC, the ubiquitous role of Patrolman Peterson in deadly decoy operations provided strong evidence that the DPD, despite its claims, was not seeking to screen violent officers with a record of brutality and indiscipline from participation in STRESS. The overwhelming pattern of white officers killing Black citizens also led the MCRC to advocate that a majority of STRESS officers should be African American, which its survey of Black residents also revealed was an essential condition for continued community support of the program.

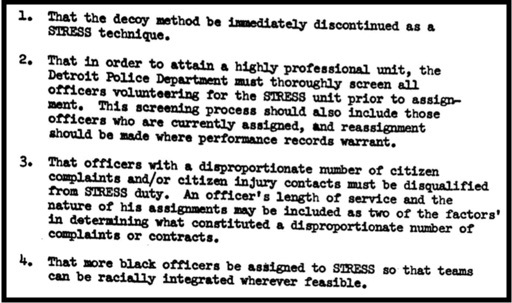

At a December 13 press conference, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission announced a series of recommendations based on its staff investigation. The MCRC did not release the full report but did highlight that a single STRESS police officer, who went unnamed, had been involved in the fatal shootings of 7 civilians and had a substantial record of police brutality complaints. The spokesperson at the press conference also stated that the investigation had revealed "injudicious use of firearms" by STRESS officers in several of the fatal shootings, again without identifying the individuals involved. The MCRC further stated that "there is no evidence" that the undercover decoy technique had reduced the robbery rate, despite DPD claims. The key recommendations included:

- Immediate discontinuation of the STRESS decoy technique

- Better procedures for screening officers who volunteered for STRESS

- Disqualification of officers with a "disproportionate number" of citizen brutality complaints and documented use of force incidents

- Addition of Black officers to integrate all STRESS units "wherever feasible" (a watered down version of the staff recommendation that a majority of STRESS officers be African American)

- Human relations training for STRESS officers, to be provided by the MCRC

DPD Commissioner John Nichols immediately responded that the decoy operation would continue because it was legal, effective, and managed with appropriate safeguards. Nichols called this decision, to retain a tactic that had resulted in the deaths of nine African Americans at the hands of white officers and that the MCRC argued did not have any positive impact on the crime rate, "a moment of truth for the community." When pressed by reporters, the police commissioner became agitated and said, "I may have to strip to my waist and tattoo on my chest that the decoy system stands."

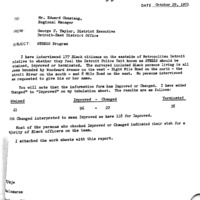

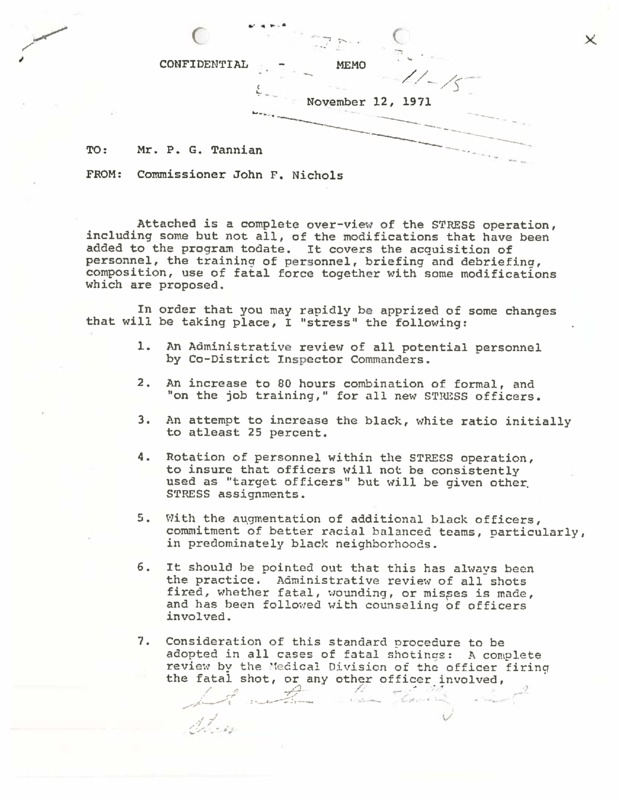

The DPD did quietly agree to work with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission to implement several of its other recommendations, but in the end changed almost nothing in response to the protests of September 1971. In a confidential memo to the mayor (gallery, below right), Commissioner Nichols pledged that the DPD would increase the operational training for STRESS officers, but he also insisted that the current screening procedures were adequate and further rejected the MCRC's offer to provide human relations sessions. Nichols did say that the department would make an effort to increase the number of Black officers from the current 10 percent to at least 25 percent of the unit, but this did not happen and STRESS was still more than 90 percent white in 1973. And finally, Nichols defended the DPD's use of force policies and the necessity of maintaining the threat of deadly force to deter fleeing felons, stating only that the department would continue to inform officers of their "right to use the revolver" under both state law and the police manual.

This phrasing summed up the STRESS mission in a nutshell--not a cautionary approach to use deadly force only a a last resort, but training officers on their "right to use the revolver" whenever the situation met the minimum legal standard.

Read the civil rights investigative reports of STRESS and the DPD's response in the gallery below, and continue to the next page for a summary of all homicides by STRESS officers between 1971-1973.

Sources

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/ Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Community Relations Bureau, RG 83-55, Michigan State Archives

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Fifth Estate Records, Labadie Photograph Collection, University of Michigan

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press, Sept. 21-23, Dec. 14, 1971

Detroit News, Sept. 22, 24, 1971

Michigan Chronicle, Sept. 25, Oct. 2, 16, 1971

Dominic Coschino, "'We Live 24/7 in Hell': Detroit's Wayne County Jail, 1968-1976" (University of Michigan: Documenting Criminalization and Confinement, 2020), https://arcg.is/1PKvDD0