1. National and Local War on Crime

What is a "War on Crime"?

President Lyndon Johnson declared a national "War on Crime" on March 8, 1965, shortly after his declaration of a War on Poverty. Johnson labeled crime a crippling epidemic hindering the progress of the nation. That being said, the target of the War on Crime was not merely criminal behavior, but rather the sociological and economic factors that the national government believed led to criminality. To that end, police and other law enforcement officials were responsible for monitoring “poverty, racial antagonism, family breakdown, [and] the restlessness of young people,” according to President Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice.

By tasking law enforcement officers to solve community-based issues, Johnson established the national War on Crime as a guerrilla warfare-style attack in poor urban black neighborhoods. Flooding the streets with police, often in plainclothes, was the presumptive solution to America’s crime ‘crisis’. This policy led to racial criminalization of black youth on the street, often for minor offenses or for nothing at all, and was not effective in combatting actual criminal behavior. In Detroit, despite a rampant influx of officers in the black community, violent and nonviolent crime rates remained relatively unchanged during the mid-1960s.

Why a War on Crime?

Ironically, the national War on Crime did not correspond with any hike in the crime rate. Instead, the War on Crime was a public policy initiative started in part to expand federal powers. Lyndon Johnson’s liberal administration believed in expanding the executive branch of the government in order to establish his ‘Great Society.’ Thus, the War on Crime became a key political initiative, alongside civil rights legislation and antipoverty programs, of liberalism in the mid-1960s.

The federal War on Crime also advanced from preconceived notions about the nature of criminality that encouraged Johnson to focus on local law enforcement and inner-city areas. Specifically, Johnson and other white liberals were concerned about the so-called 'pathology' of black youth in impoverished neighborhoods. The personality and behavior of ‘troubled’ youth, especially racial minorities, became a central tenet of the War on Crime. In order to curb 'crime and disorder' in impoverished urban communities, the Johnson administration employed the police to establish order and merged crime control with social welfare programs.

Correlation between National and Local Government

The policies initiated by the federal government under Lyndon Johnson quickly trickled down into local governments across the country. Local police departments received exorbitant amounts of government funding contingent on the following of national policy. Community-improvement programs, officer training regimens, and the daily tasks of law enforcement all reflected these new federal priorities. In a bipartisan consensus, state officials enforced national standards by supporting the ramping up of spending on law enforcement as well. In Michigan, Governor George Romney (Republican) worked closely with Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanagh (Democrat) to establish a large bureaucracy focused entirely on law enforcement.

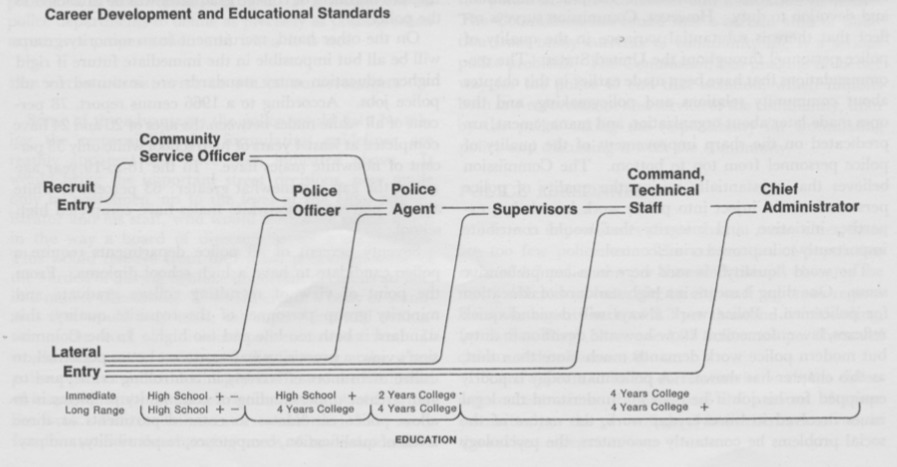

President Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice (CLEAJ) outlined national standards for functions of police officers, educational training, coordination of services with community organizations, policy creation, and more. Click on documents to the right and in the gallery below to explore various programs and guidelines from the CLEAJ's report, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society, designed to implement the vision of Johnson's 1965 declaration of War on Crime.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations /Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society (Washington: GPO, 1967)

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)