Pingree Street Conspiracy

NOTE: THIS PAGE IS UNDER ACTIVE REVISION AS OF OCT. 1, 2022. Please do not cite or utilize it until this temporary headnote changes. Information drawn from a number of Detroit Free Press articles written by Howard Kohn is being reviewed/revised/reframed--with a note of appreciation to journalist Bart Bull for concerns raised and information provided. The main revisions are to the "Detroit Free Press expose" subsection of the "Police Drug Trafficking in the Tenth Precinct" section. The original version published in 2021 can be found at the bottom of the page under the Sources list. Posted by Matt Lassiter, 10-1-2022.

Police corruption in the field of narcotics enforcement is endemic and inevitable. The criminalization of heroin and other lucrative but illegal drugs brings enormous profits into the underground market and creates clear opportunities for corruption by the undercover officers who police them. This pattern is related to the extensive corruption of law enforcement officers in other so-called "vice" markets, such as prostitution and gambling, but also far more pervasive because of the tens of millions of dollars that have flowed to urban police departments through federal funding of the "war on drugs." The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, passed by a Democratic-controlled Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon, channeled huge resources to Detroit and other major American cities and ramped up street-level narcotics enforcement during this era.

That same year, the New York Times broke the story of widespread narcotics corruption in the New York Police Department, leading to explosive hearings by the Knapp Commission in 1971. The Knapp Commission found that half of all officers in the NYPD engaged in corrupt activities such as planting evidence and taking bribes, and that undercover drug enforcement in particular had led to "the nearly complete corruption of narcotics police," including protection for favored dealers and the resale of more than $32 million of confiscated heroin on the street. Historian Eric Schneider concluded that undercover narcotics officers in New York City often acted "in ways indistinguishable from the dealers they policed" and that "in the war against drugs, some of the biggest dealers were the warriors themselves."

In Detroit, narcotics corruption among police officers during the 1960s and early 1970s was definitely extensive, but the full scope of the problem is unknowable, because of the secretive nature of undercover operations and criminal conspiracies, as well as the failure of city and state leaders to authorize an investigation on the scale of the Knapp Commission. The Detroit Police Department did conduct multiple internal investigations of alleged narcotics corruption by individual officers during these years, including several that resulted in firings or prosecutions, but critics also charged that the DPD sought to minimize and obstruct the independent law enforcement investigation into the Tenth Precinct that began in 1972.

The so-called "Pingree Street Conspiracy" investigation centered on the Tenth Precinct, a low-income and almost all-Black area in Northwest Detroit where vice and narcotics markets had long flourished with police complicity. (The epicenter of the investigation, at 12th and Pingree, was less than a half mile from the "blind pig" where the 1967 Uprising began). The Pingree Street investigation led to the indictment of ten police officers, which many activists and also the internal investigators believed was only the tip of the iceberg. Only three officers were convicted, one for narcotics trafficking and two for obstruction of justice, during a prosecution marred by witness intimidation and other controversies. Community activists charged the DPD with a massive coverup, demanded a full investigation by an independent citizens' grand jury, and alleged that even some commanding officers took bribes arranged and collected by undercover cops on the street. The Detroit Free Press published similar allegations in a bombshell 1973 expose, but then soon fired its undercover investigative reporter for fabricating aspects of his news stories, leading to even more uncertainty about the elusive truth regarding the extent of police corruption in the war on narcotics.

This page addresses the broader issue of DPD narcotics corruption through a focus on the "Pingree Street Conspiracy." It is important to emphasize that this organized criminal network, uncovered in the Tenth Precinct, definitely did not encompass the full scope of narcotics corruption by Detroit police officers during this time period. Black community activists had long accused the DPD of pervasive narcotics corruption (see headline below), and during the early 1970s a wide range of civil rights and leftist groups mobilized against the heroin traffic, which they blamed in part on police complicity. The formation of STRESS in 1971 also coincided with the escalation of Detroit's war on drugs, and narcotics enforcement was one of the primary responsibilities of this undercover operation. Radical groups accused STRESS of narcotics corruption in the 1972 Rochester Street Massacre, the 1973 shootout that led to the DPD manhunt against three Black anti-narcotics activists, and more generally in its everyday operations. It is important to note that there is very little hard evidence of STRESS narcotics corruption, although such allegations circulated widely among radical groups in the anti-STRESS movement. "All black people know about police complicity on drugs, about STRESS officers going into dope houses and getting payoffs," Ron Lockett of the Committee to Abolish STRESS said in 1973. "They bring dope to dope houses--I myself have seen this."

Internal Investigation of Police Drug Trafficking in the Tenth Precinct

In May 1972, the head of the New Detroit Committee (NDC) publicly called for an investigation into the reasons for Detroit's growing narcotics problem and emphasized "the strong feeling of people in our poorer community"--meaning the poor and mostly Black neighborhoods where street-level narcotics markets flourished--"that the drug traffic would not exist if law enforcement people were not involved." DPD Commissioner John Nichols responded with extreme anger, attacking NDC head Lawrence Doss for an "irresponsible statement" that was a "direct insult" to the undercover police officers risking their lives to stop the scourge of illegal drugs. Yet in the same press conference, Nichols conceded that recent internal inquiries by the DPD had resulted in the prosecution or termination of eight police officers for narcotics-related corruption in the previous year alone, with multiple cases still pending. In truth, no one knew the scope of the problem, and both logic and history made clear that the dirty cops identified by the DPD must have represented only a fraction of the overall pattern of police criminality in the narcotics trade.

The New Detroit Committee received behind-the-scenes support from the organized crime division of the state attorney general's office. Despite his public protests, Commissioner Nichols eventually responded to the controversy by agreeing to establish a special task force to investigate the allegations. Vincent Piersante, the head of the organized crime division, recalled later that they "had a devil of a time" convincing John Nichols to take this step, and complaints that the DPD hierarchy was obstructing the task force would continue over the next several years.

Bennett Task Force and DPD Interference. The Tenth Precinct investigation was run by Lt. George Bennett, an African American police officer appointed by Commissioner John Nichols in response to criticism that the DPD was not willing to clean its own house. Bennett almost immediately protested directly to the mayor's office that the DPD hierarchy, including the commissioner, were resisting and obstructing his investigation. He eventually moved his 12-member team out of DPD headquarters and into the state attorney general's office because of continued concern about interference by high-ranking law enforcement officials. Bennett's team specifically worried that there would be "leaks to the crooked cops, even from big guys in the department." The head of the Guardians of Michigan even accused the DPD hierarchy of supporting Bennett's investigation as long as the focus remained on corrupt African American officers, but then telling him to "lay off . . . as soon as he uncovered white names."

At the same time, Bennett's task force enjoyed a high degree of autonomy because of the Michigan Supreme Court's recent clarification of the independence of citizen grand juries to conduct their own criminal investigations, a response to the interference of Prosecutor William Cahalan when a grand jury sought a more thorough investigation of the Rochester Street Massacre. Bennett also worked directly with the Wayne County Organized Crime Task Force, allowing him to call witnesses before the grand jury with the assistance of a more independent prosecutorial division. Bennett's task force continued to allege that they faced obstruction and threats from within the DPD for the five-year duration of the Pingree investigation and trial, through the end of 1975, as discussed below.

Grand Jury Indictments. In December 1972, Bennett's task force raided the DPD's Tenth Precinct station house and found large quantities of heroin and cocaine stashed in small unmarked bags in various places--none of it in the evidence room in line with rules and procedures. In January 1973, the task force and county prosecutor from the organized crime division began taking secret grand jury testimony from narcotics dealers cooperating with their investigation. Then in late April, investigators on Bennett's special task force requested sealed indictments against 22 police officers for involvement in heroin trafficking and other narcotics-related crimes. It is crucial to highlight that the DPD and its close ally, Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan, did not approve these indictments in advance, because of the arrangement of the task force and its ability to work directly with the citizens grand jury. All of the indicted officers worked or had worked in plainclothes and undercover narcotics operations in the Tenth Precinct, and most had at least five years on the force. Five were sergeants and seventeen were patrolmen; thirteen were white and nine were African American.

On May 23, 1973, the citizens grand jury indicted 10 of the 22 DPD officers recommended for prosecution, along with 16 civilian co-conspirators, on charges ranging from narcotics trafficking and obstruction of justice to murder, kidnapping, bribery, and robbery. Prosecutor William Cahalan announced the charges and promised to deal a major blow to narcotics crime in Detroit, while Police Commissioner John Nichols stood beside him and pledged that there would be no DPD coverup and that all guilty officers would be brought to justice.

Detroit Free Press Investigation Section: Currently Under Revision

THIS SECTION IS ACTIVELY UNDER REVISION

The Left Demands a Full and Independent Investigation

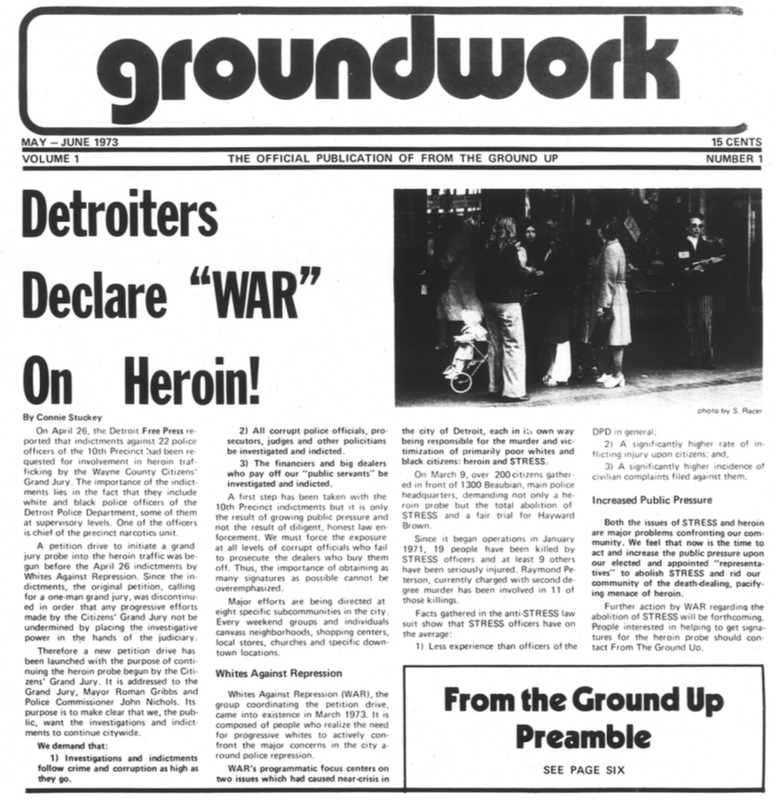

The indictments of DPD officers in the Tenth Precinct and the sensational media coverage generated a wave of protests by radical activists in Detroit's anti-STRESS movement, including accusations that the police commissioner and the prosecutor wanted to limit the scope of the Bennett task force inquiry as much as politically possible. From the Ground Up, the white radical anti-STRESS organization affiliated with the Labor Defense Coalition, provided extensive coverage of the Pingree Street Conspiracy in its publication Groundwork (right) and demanded that the city of Detroit fight a real war on heroin. These activists formed a new ad hoc group, Whites Against Repression (WAR), to lead a petition drive demanding an expansion of the police corruption probe through empowerment of an independent citizens grand jury that did not rely on the prosecutor to bring charges. WAR also labeled STRESS and the police-facilitated heroin trade to be the twin crises confronting, and killing, the poor and Black citizens of Detroit. The group held several protests outside of the DPD's downtown headquarters in spring 1973 and issued three specific demands, all based on the expectation that the police department and Prosecutor Cahalan would cover up the breadth and depth of law enforcement narcotics corruption and protect higher-ranking officials by limiting the probe to a few cops on the street.

- "We demand that investigations and indictments follow crime and corruption as high as they go"

- "All corrupt police officials, prosecutors, judges and other politicians be investigated and indicted"

- "The financiers and big dealers who pay off our 'public servants' be investigated and indicted"

On May 16, even before the announcement of the police indictments, From the Ground Up sponsored a community forum with other anti-STRESS activists called "Heroin: Who Profits? Who Suffers?" (full transcript in gallery below, left). The event featured Hayward Brown, a Black anti-narcotics activist who had recently been acquitted of murdering a police officer in the episode than inspired the DPD's manhunt, and who had testified in his trial that DPD officers protected heroin dealers and therefore did irreparable harm to the inner-city African American community. Overall the forum portrayed the American war on drugs as a racist, capitalist smokescreen to arrest and incarcerate the poor and Black "victim addicts" while letting the "big dealers" ravage their communities with the assistance of "corrupt police and politicians." Kenneth Cockrel, the leader of the Labor Defense Coalition, insisted that the indictments of a dozen or so street-level police officers would bring the process "no closer to the top and to the source of that criminality." Justin Ravitz, the co-founder of the Labor Defense Coalition and a recently elected Wayne County Recorder's Court judge (who later presided over the Pingree trial), accused the police of "wholesale illegality" in narcotics enforcement operations against low-level addicts. Ravitz also brought the police conspiracy issue back to STRESS, pointing out:

From the Ground Up and the Labor Defense Coalition continued to attack the DPD and Wayne County Prosecutor for covering up police narcotics corruption throughout the summer and fall of 1973, during a mayoral election that revolved around the fate of STRESS and with the Pingree Street trial on the horizon. Groundwork, the newsletter started by the groups, published features such as "Heroin: The Profitable Plague" and emphasized that trafficking operated through "payoffs, bribes, and kickbacks to corrupt politicians and police which allows it to operate and expand with greater immunity." Kenneth Cockrel of the Labor Defense Coalition explained that African American neighborhoods wanted to eradicate dope houses and banish heroin dealers but had nowhere to turn, because reporting drug crime to the police department would be "like calling the dope man to bust the dope man." Another Groundwork article attacked John Nichols and William Cahalan, arguing that the police commissioner's "energies have been spent covering up illegality in his department rather than exposing it" and that the prosecutor would have preferred "no investigation and no indictments" based on his record of "covering up racist police activity, brutality and murder."

From the Ground Up also warned, after the announcement of indictments of 10 DPD officers:

The gallery below contains four From the Ground Up and Labor Defense Coalition publications from the spring and summer of 1973 that examine law enforcement complicity in heroin trafficking and charge the DPD and Wayne County Prosecutor with a coverup of its scope.

The Pingree Street Conspiracy Trial and a Limited Verdict

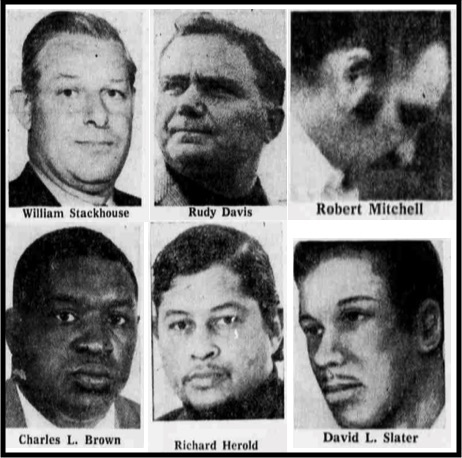

The May 1973 indictment secured by Bennett's task force listed 16 civilians charged with narcotics trafficking, all but one African American males, and 10 DPD officers, half of whom were African American. The first six listed below were also publicly named in the Detroit Free Press report of April 29, 1973.

- Sgt. Rudy Davis, a white male, head of the narcotics squad in the Tenth Precinct

- Sgt. William Stackhouse, a white male

- Ptr. Robert Mitchell, a white male

- Ptr. Charles Brown, an African American male

- Ptr. Richard Herold, an African American male. (Herold also was present in the immediate aftermath of the Rochester Street Massacre, fueling suspicions among community activists that its mysterious origins were linked to a narcotics 'turf war').

- Ptr. David Slater, an African American male

- Sgt. Carlos Gonzalez, listed as a white male

- Ptr. Willie Peeples, an African American male

- Ptr. Anthony Lopez, an African American male

- Daniel O'Mara, a retired DPD officer and white male

Two of the civilian defendants were shot and killed before trial, which raised suspicions about whether an interested party might have sought to silence them before they turned state's evidence and testified against their alleged co-conspirators. Several other took plea deals. Then the first attempt to prosecute the remaining defendants ended in a mistrial after another one of the civilians took a deal during the proceedings and agreed to testify against others. Before the second trial began, Patrolman Anthony Lopez also agreed to testify for the prosecution, which dropped charges and placed him and his family in protective custody. The second trial of the remaining defendants, dubbed the "Pingree Street Sixteen," finally got underway in July 1975.

Deputy Chief George Bennett, the African American head of the special investigative task force (who was promoted from lieutenant in 1974), stated that he faced substantial harassment and intimidation, including from within the DPD, between the announcement of indictments and the culmination of the trial. In June 1973, Bennett reported a threat against his life, a $20,000 contract offer for a hit man, and subsequently received protection on the orders of Police Commissioner John Nichols. Two African American police officer associations, the Guardians of Michigan and Concerned Police Officers for Equal Justice, publicly stated that they did not trust the DPD to protect Bennett and offered instead to do so themselves as volunteers. Then in a pretrial hearing, Bennett testified that he had personally witnessed a DPD officer make a heroin drop to a street dealer and then report back to Sgt. Rudy Davis, the white officer indicted as a ringleader of the Tenth Precinct conspiracy operation. In a possible revenge move, Patrolman Richard Herrold, another indicted officer, later testified that Bennett had asked him to plant evidence on Sgt. Rudy Davis and then offered him $50,000 to kill either Davis or Commissioner John Nichols. Another unindicted DPD officer who was part of the Tenth Precinct narcotics squad also testified that Bennett had asked him to plant narcotics on several of the indicted officers. Anonymous sources within the department labeled him as "bitter and vengeful black man who had framed the white officers" because he once sued the DPD for racial discrimination. George Bennett insisted that these lies were part of a deluge of "harassment, intimidation, and threats" that he and other task force members faced from a corrupt and organized conspiracy inside the DPD.

The Pingree Street Conspiracy trial revealed extensive police criminality in the narcotics trade but also necessarily remained narrowly focused on the individual police defendants, several of whom had been charged with obstruction of justice, rather than exposing any broader networks of internal DPD corruption. At the same time, the defense argued that drug dealers and addicts were falsely accusing police officers in exchange for immunity for their own crimes. Highlights of the proceedings (full testimony in gallery below) include:

- Harold Chapman, a heroin and cocaine dealer given immunity for his testimony, stated that Sgt. Rudy Davis provided him with drug deliveries 2-3 times a week from 1970 through January 1973 and that he paid Davis around $50,000 per year. Chapman claimed that he first encountered Sgt. Davis when the officer led an undercover DPD raid on a dope house, confiscated the contraband, and made no arrests. After that, the two men allegedly devised an arrangement where Sgt. Davis sold cocaine and heroin to Harold Chapman; sometimes they made the exchange in the parking lot of the Tenth Precinct station house. Sgt. Davis also told Chapman, according to the witness's testimony, that his own "boss" was a Lieutenant Porter (presumably a pseudonym) in the DPD.

- Larry McNeal, a narcotics dealer who was part of the Guido Iaconelli/Milton Battle syndicate and testified under a grant of immunity, stated that he saw officer Daniel O'Mara enter a dope house for payoffs and that Patrolman David Slater and Patrolman Willie Peeples raided a dope house and confiscated drugs but made no arrests, with the complicity of Sgt. Carlos Gonzalez. The three officers also allegedly took payoffs from McNeal's brother Roy, known as "Alabama Red" and a major operator in the Milton Battle network, and sometimes called him or went to his residence. McNeal also testified that he observed Patrolman Robert Mitchell and Sgt. William Stackhouse meet with "Alabama Red" in his Pingree Street headquarters, and described a dope house raid led by Sgt. Rudy Davis and Patrolman Mitchell with eight other officers who confiscated drugs but made no arrests. (Overall McNeal stated that police had raided his brother's dope houses 37 times and only arrested him once). McNeal further claimed to have witnessed Patrolman Richard Herrold visiting the dope house run by "Alabama Red" for payoffs.

- Wiley Reed, part of the Guido Iaconelli/Milton Battle trafficking operation who was given immunity and protective custody by the task force, testified that they paid off officers to protect their dope houses. Reed described giving payouts to, and occasionally receiving narcotics from, Sgt. Rudy Davis, Patrolman Robert Mitchell, and the now retired officer Daniel O'Mara, among other DPD officers. Reed even claimed that he personally delivered a monogrammed diamond ring to Rudy Davis as a token of appreciation from Milton Battle. Reed depicted a narcotics market that was so wide open that one block at 12th and Pingree Street contained 27 protected dope houses.

- Peaches Miles, a self-described addict and prostitute, testified that she supplied Ptr. Robert Mitchell with tips on unprotected dope houses for the Tenth Precinct narcotics squad to raid and then bring into the bribery network. In exchange, Mitchell allegedly provided her with heroin and cash that allowed her to open her own dope houses and move into the distribution side of the market. Miles also effectively described Ptr. Mitchell as her "pimp," providing protection whenever she needed it.

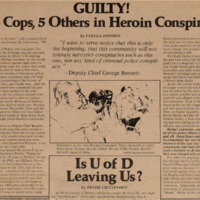

Verdict. On December 20, 1975, the majority-Black jury convicted half of the "Pingree Street Sixteen" defendants, including three DPD officers and five civilians. Six DPD officers were acquitted in a verdict that appeared to represent a compromise by a divided jury. (Journalists later uncovered that ten of the jurors wanted to convict all defendants on all counts, but two white jurors held out for acquittals of every police officer involved). The defense clearly succeeded in impugning the credibility of the prosecution witnesses, most of whom were admitted drug dealers, and in some cases admitted killers, who provided evidence in exchange for limited grants of immunity. It is notable, given the detailed testimony and other evidence gathered by the task force, that only one low-level police officer was found guilty on the charge of conspiracy to distribute narcotics, and all of the rest were acquitted. Three were found guilty of obstruction of justice, a capacious charge that covered the taking of bribes to protect drug traffickers from arrest. It is also notable that the jury, consisting of thirteen African Americans and five white members, acquitted all of the African American defendants except Richard Herrold, who had previously been arrested in Canada for cocaine trafficking. The guilty officers:

- Sgt. Rudy Davis, the head of Tenth Precinct narcotics operations and accused ringleader of the police conspiracy to provide confiscated heroin and cocaine to traffickers, convicted of obstruction of justice but acquitted of conspiracy to distribute narcotics. He received a 3-to-5 year sentence from Judge Justin Ravitz, and a cash penalty that was paid by members of his church and the Lieutenants and Sergeants Association of the DPD. (Davis also was convicted of obstruction of justice for taking bribes in a separate drug corruption trial in 1974).

- Ptr. Robert Mitchell, guilty of conspiracy to distribute narcotics and of obstruction of justice.

- Ptr. Richard Herrold, guilty of obstruction of justice and acquitted of conspiracy to distribute narcotics.

George Bennett's task force hoped that the conviction of the ringleaders of the Tenth Precinct operation, especially Sgt. Davis and Ptr. Mitchell, would convince the officers to turn state's evidence and violate the "Blue Curtain" policy of shielding the criminality of other police officers and expose any broader networks of police corruption. However, Davis's acquittal on the more serious charge of conspiracy to distribute narcotics, which carried a much lengthier sentence than obstruction of justice, reduced his incentive to seek a deal.

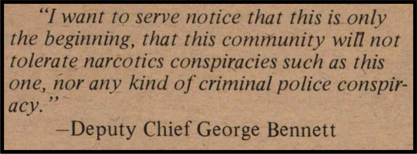

Deputy Chief George Bennett, although clearly disappointed at the mixed verdict, expressed satisfaction that "we got the core." Bennett left the courthouse with a warning for dirty cops and their enablers:

This promise turned out to be more optimistic than realistic. In a retrospective on the Pingree Street Conspiracy, the Detroit Free Press asked whether police corruption in the lucrative underground narcotics market could ever be eradicated and noted that attorneys for both the prosecution and the defense all began "talking of legalization as the only answer to this country's heroin problem."

Drug corruption continued to plague the DPD during subsequent decades, even as the department and city government came under Black political control, and ultimately brought multiple investigations by the FBI in recognition that the DPD's internal affairs processes were not capable of breaking down the "Blue Curtain." These corruption investigations and criminal police conspiracies will be covered in our project's follow-up website, Crackdown: Policing Detroit through the War on Crime, Drugs, and Youth, about the 1974-1993 period.

The gallery below contains Pingree trial testimony alleging police criminality from three key prosecution witnesses, all admitted narcotics dealers who received limited immunity for their cooperation, and the Ann Arbor Sun's report on the testimony of a fourth witness.

Sources:

Pingree Street Conspiracy Trial-Recorders Court File #73-03636, Box 1, William Lucas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Thomas V. LoCicero, "The Drug Conspiracy Trial that Rocked Detroit's 10th Precinct," Detroit Free Press, September 26, 1976

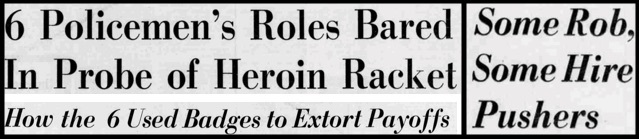

Howard Kohn, "6 Policemen's Roles Bared in Probe of Heroin Racket," Detroit Free Press, April 29, 1973. Additional Pingree Street Conspiracy coverage in Howard Kohn series in Detroit Free Press, April 15-20, 1973

Pingree Street Trial coverage in Ann Arbor Sun, July-Dec. 1975

Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1972, May 21, 24, April 29, June 25, 1973, Sept. 6, 1974, July 18, 1975, Oct. 5, 1976

Michigan Chronicle, May 6, 1972

Groundwork coverage from The American Radicalism Collection: Part 4: Twentieth-Century Social, Economic, and Environmental Movements, Michigan State University, Political Extremism & Radicalism, Gale Primary Sources

Percy Key in Michigan Chronicle, July 21, 1973; March 5, 1977

Eric Schneider, Smack: Heroin and the American City (2008)

Note: This is the original subsection on the Detroit Free Press expose, published in 2021, as previously included in the first section of this page above. This is provided for the record and is superseded by the revised "Police Drug Trafficking in the Tenth Precinct" section above. (More information will be added to this note when the revisions to this page are complete).

Detroit Free Press expose. In the spring of 1973, the Detroit Free Press published the first bombshell report from reporter Howard Kohn's two-year investigation into the criminal activities and organized networks of police officers who participated in the heroin trade in the city of Detroit. The expose identified six corrupt police officers by name but stated that the newspaper had specific information on thirty in total, all of which Kohn had turned over to the special task force. According to Kohn's series, informed law enforcement sources believed that at least 200 members of the Detroit Police Department were involved. It is notable that the first public exposure of a widespread police conspiracy came from the Free Press, whose reporter interviewed more than 100 heroin dealers and addicts and then confirmed the information with task force investigators, and in some cases provided it to them.

The Free Press investigation centered on the Tenth Precinct, a low-income and almost all-Black area in Northwest Detroit where vice and narcotics markets had long flourished with police complicity. (The epicenter of the investigation, at 12th and Pingree, was less than a half mile from the "blind pig" where the 1967 Uprising began). The evidence revealed that more than one network of veteran officers had both supplied and extorted heroin dealers for years and also provided protection to many of the city's major trafficking operations. The named white officers appeared to be running their own sophisticated criminal organization, while several of the Black officers had initially become involved under the direction of the recently deceased Henry Marzette, an African American former police officer who became Detroit's most powerful "heroin boss" during the 1960s, in part by hiring or bribing former colleagues. The six named police officers, half of whom were white and half of whom were African American, included Sgt. William Stackhouse, Sgt. Rudy Davis, Patrolman Robert Mitchell, Patrolman Charles Brown, Patrolman Richard Herold, and Patrolman David Slater. Their documented criminal activity included:

- Employing a network of heroin street dealers

- Supplying these dealers with heroin by robbing other dealers at gunpoint, confiscating the narcotics from suspects in exchange for not making an arrest, and stealing from the evidence room

- Leaking information about police raids and informants to dealers in exchange for payoffs

- Providing 'protection' from investigation and arrest to several major traffickers and dealers in their networks

- Extorting bribes directly from dealers not on their active payroll and/or forcing dealers to buy heroin from the police officers for double the market value

- Beating, and possibly in some cases killing*, heroin dealers and informants who refused to play ball

*In October 1972, two known drug dealers, Edward Chatman and Raymond Walker, were murdered in identical unsolved execution-style slayings, and in 1976, the Detroit Free Press reported that both homicide files had mysteriously gone missing from headquarters and that an active DPD officer was the suspect in both.

*In 1973, undercover narcotics officer Percy Key was indicted for manslaughter for shooting an unarmed man from Alabama from a car; in 1974 Key and another officer were indicted for conspiracy to distribute heroin, making it likely that the 1971 homicide was a drug dispute.

- Sgt. Rudy Davis, identified in the Free Press investigation, was the head of the narcotics squad in the Tenth Precinct and stood accused of distributing heroin confiscated during drug raids back to more than 25 dealers in his network for double the market value in exchange for protection from arrest. The Free Press also reported that Sgt. Davis provided protection for Jesse James, one of the city's leading heroin traffickers, and that higher-up officials at DPD headquarters had sought to protect Davis from the Tenth Precinct investigation, presumably because they shared in the profits. The head of the DPD's internal investigation described Davis in off-the-record comments to reporters as the "bag man for the third floor," a reference to upper-level officials at DPD headquarters.

- Sgt. William Stackhouse was accused of extorting bribes from dozens of heroin dealers over a 15-year period, beating those who refused to pay and protecting those who did from police investigation. According to several sources who worked in the illegal trade, Sgt. Stackhouse also provided protection for the major heroin wholesaling operation of John Classen after he was sentenced to prison in 1971.

- Patrolman Robert Mitchell worked as an enforcer in Sgt. Davis's and Sgt. Stackhouse's extortion racket and personally guaranteed protection for Guido Iaconelli, a suburban-based heroin supplier to Detroit.

- Patrolman Charles Brown was accused by multiple heroin dealers of robbing them at gunpoint, charges confirmed by law enforcement sources. Brown's partner, Patrolman William Slappey, died on March 11, 1970, when the two of them were attempting to rob a drug dealer, an incident the DPD wrongly classified as a police fatality in the line of duty.

- Patrolman Richard Herold was accused of a broad range of drug-related crimes, including heroin distribution, and had been arrested in Toronto in January 1973 on cocaine trafficking charges. Patrolman Herold allegedly worked for Henry Marzette, the former cop who became Detroit's largest narcotics distributor in the 1960s, and helped to sabotage investigations of Marzette's network from inside the DPD. Richard Herold also was present in the immediate aftermath of the Rochester Street Massacre, leading to suspicions among law enforcement investigators (as well as community activists) that its mysterious origins were linked to a narcotics 'turf war' over "which heroin dealers worked for which officer."

- Patrolman David Slater was accused of demanding monthly payments from heroin dealers at gunpoint as well as robbing narcotics addicts inside dope houses. Slater also reportedly worked for Henry Marzette's operation.

Three weeks after the Free Press article listing these six officers appeared, reporter Howard Kohn alleged that he had been abducted, held for twelve hours, and narrowly escaped being murdered by a "hired gunman." The Free Press swore that it would not be "intimidated by violent tactics," but the newspaper soon fired Kohn for not informing his editors that he had bought a gun for self-defense and for omitting this part of the story from police investigators. The DPD charged Kohn with filing a false police report, which appeared to be an act of retribution against a crime victim who had blown the whistle on massive police corruption. The Detroit Free Press soon dramatically scaled back its investigations of police complicy in the narcotics market, leading to accusations that the newspaper had caved in to pressure from the DPD and its allies.