Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU)

What was the Tactical Mobile Unit?

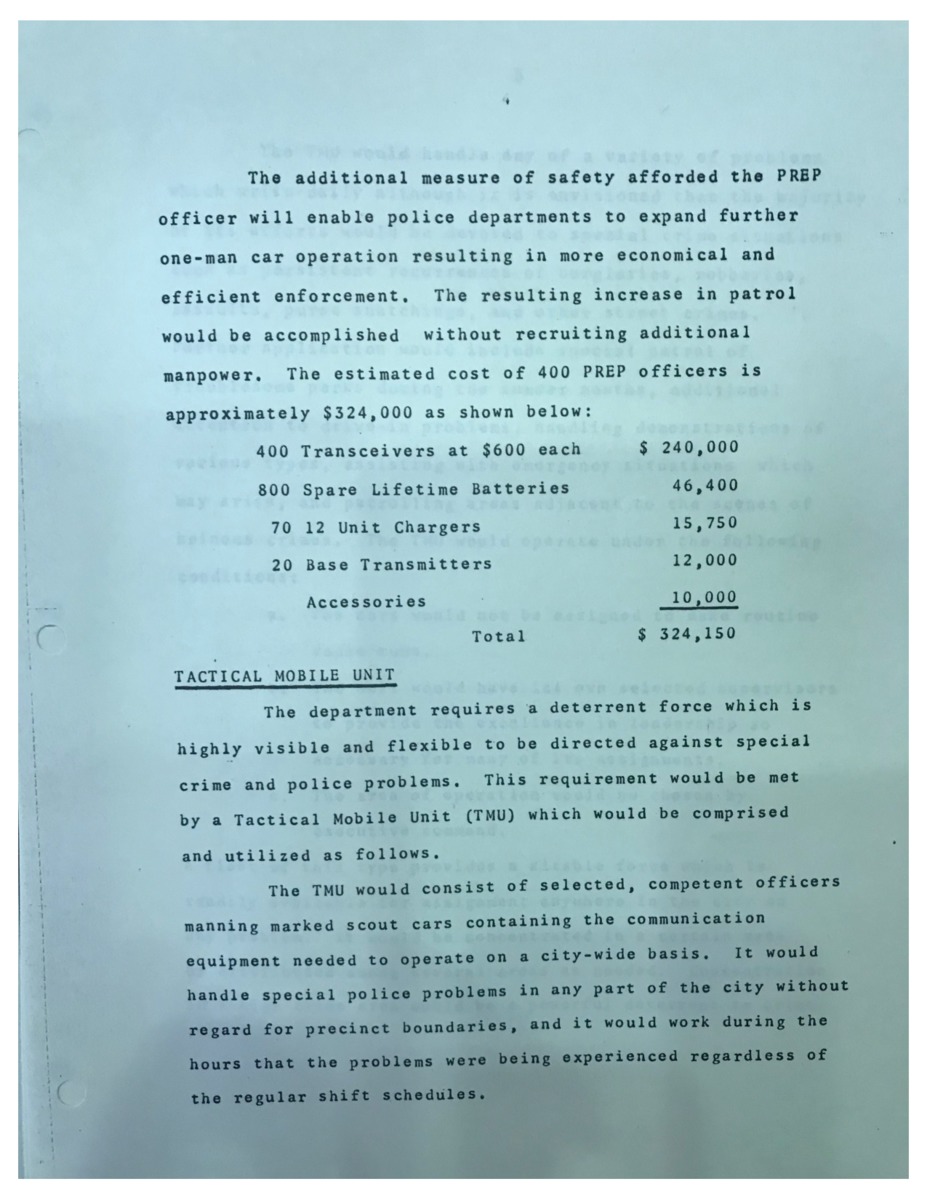

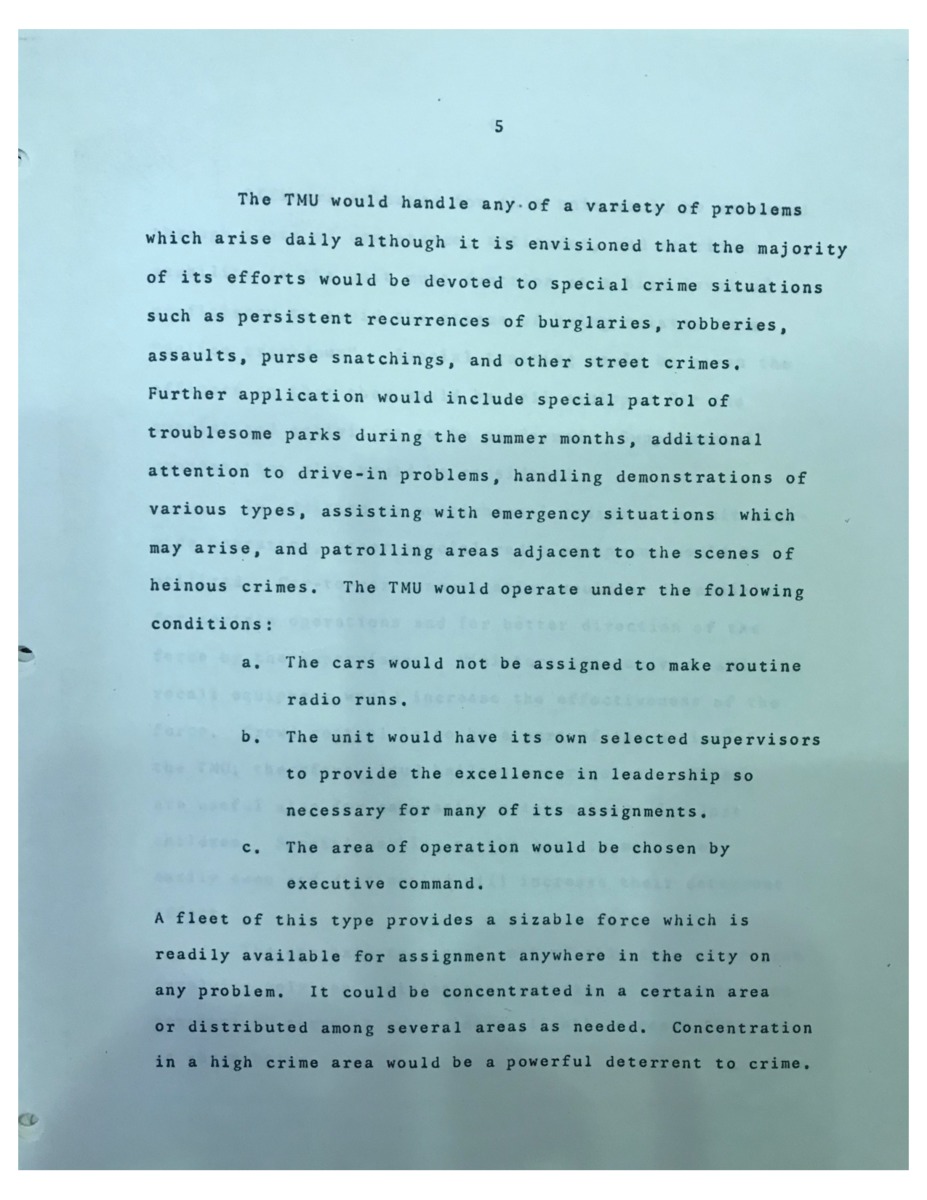

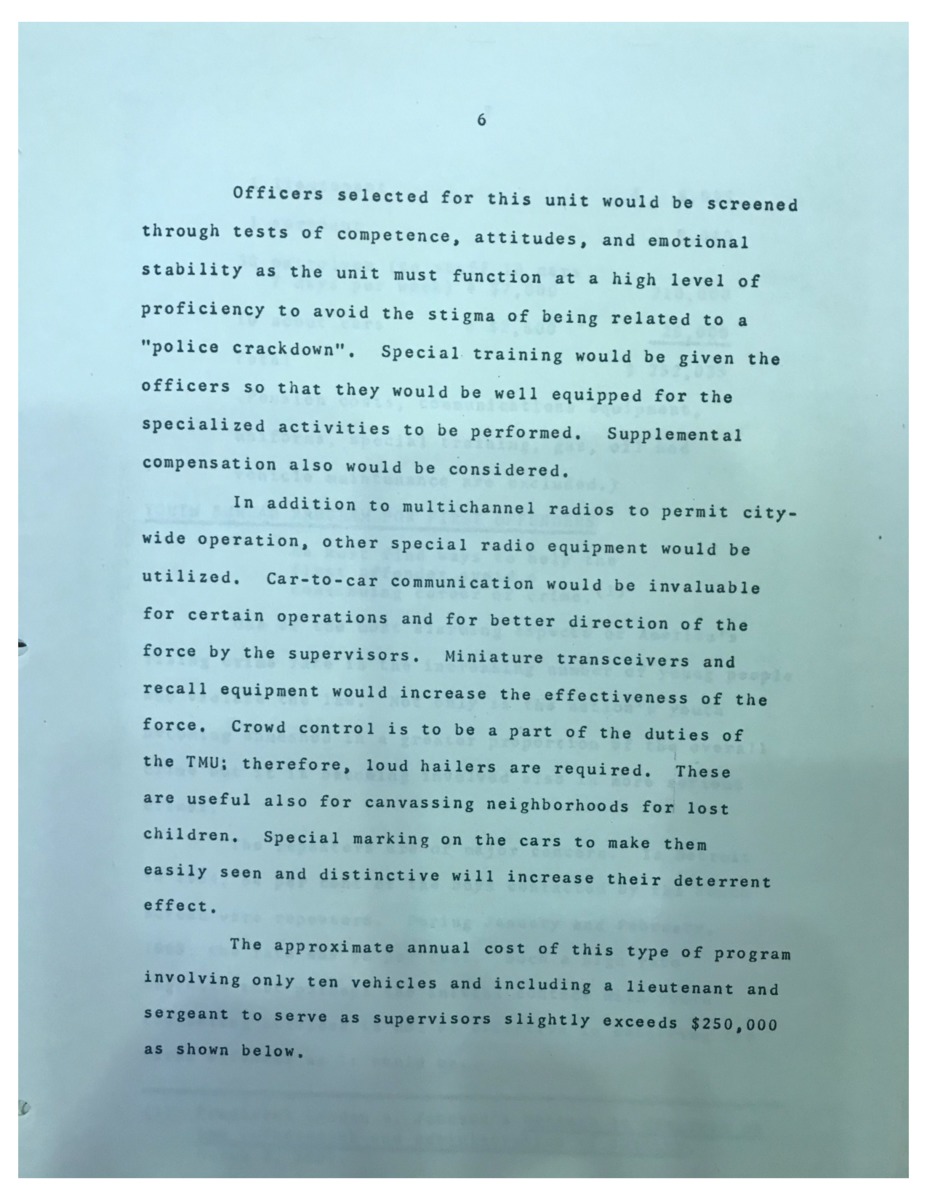

DPD Commissioner Ray Girardin was the architect of the Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU). In 1965, he proposed the unit to the Mayor's Task Force on Federal-Urban Programs as a "deterrent force" that would be deployed across precinct lines and focus on "high crime," a euphemism for poor black neighborhoods and the downtown business corridor.

Girardin argued that the TMU would "handle special police problems" that DPD patrolmen lacked the resources to combat--highlighting burglaries, robberies, assaults, and other street crimes. Additionally, he tasked the TMU with patrolling "troublesome" areas, dealing with emergency situations, and aiding in the supervision of areas near crime scenes.

Finally, Girardin's proposal envisioned the TMU as a front-line unit to control "demonstrations of various types"--which meant civil rights protests, including the growing campaign against police brutality. On April 14, two weeks after receiving Girardin's report, Mayor Cavanagh proposed the creation of the TMU to the Common Council. The proposal was part of a larger project of incorporating technology and police militarization into the War on Crime.

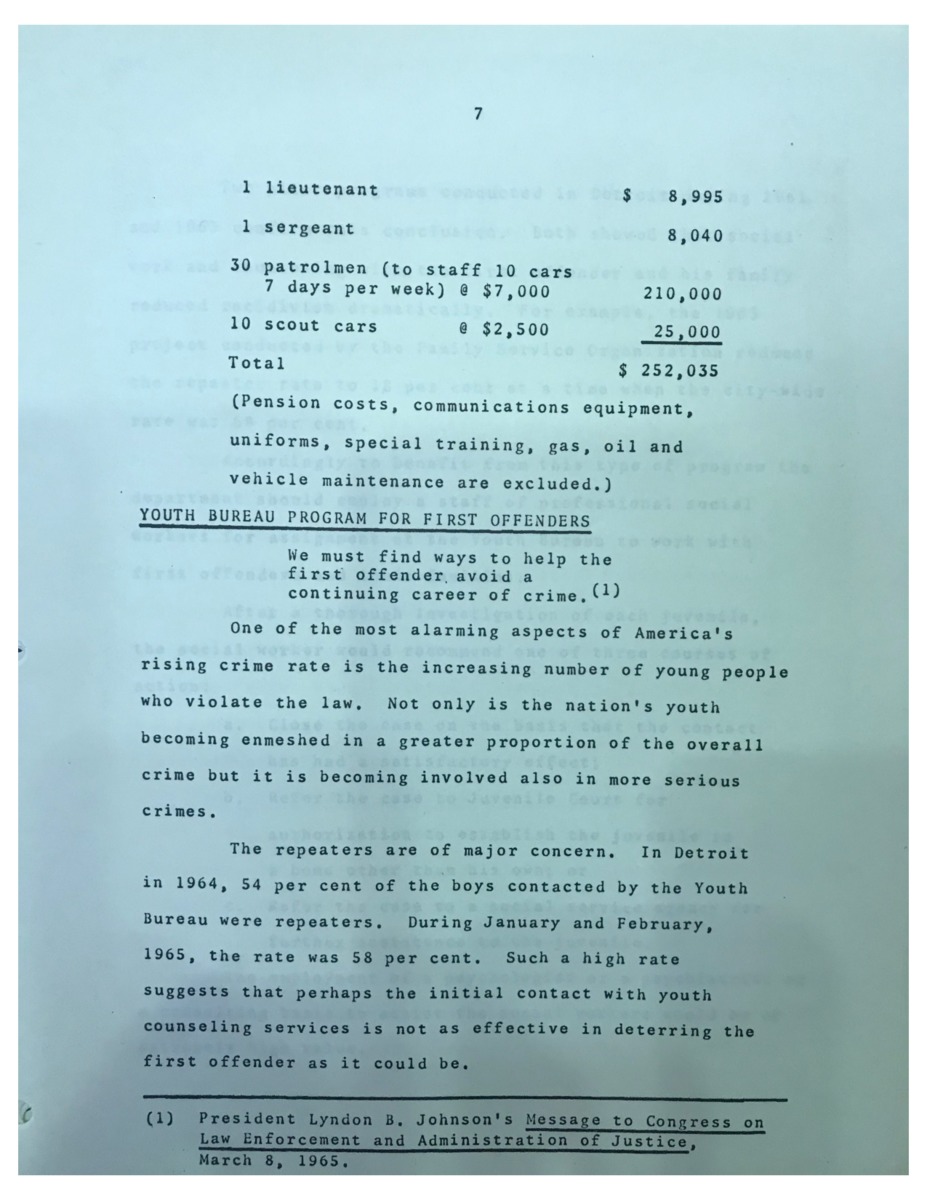

Below are excerpts from Girardin's report to Mayor Cavanagh envisoning the operation of the TMU.

TMU Activity 1965-1973: 100x More Stops than Arrests

The TMU, a highly militarized unit, expanded discretionary policing and racial profiling on a mass scale and stopped hundreds of thousands of Detroit residents without cause during the second half of the 1960s. Even without an archival smoking gun, the proof of the TMU's mass criminalization of motorists and pedestrians in Detroit is evident in the dry numbers from the DPD's annual reports.

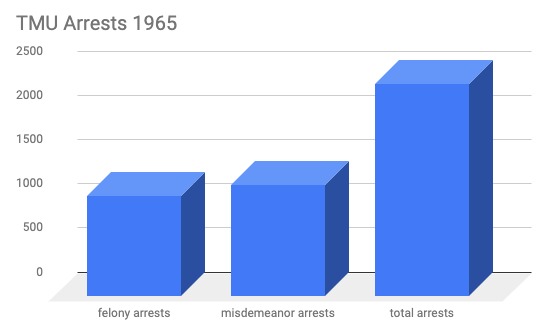

In 1965, its first year of operation, the TMU made 2,398 total arrests (bottom left). Of these, 1,135 were for felonies and 1,263 for misdemeanors. The 1965 annual report did not provide information on total stops by the TMU, but future DPD reports added the data for persons and automobiles investigated, and juveniles detained, in addition to arrest data.

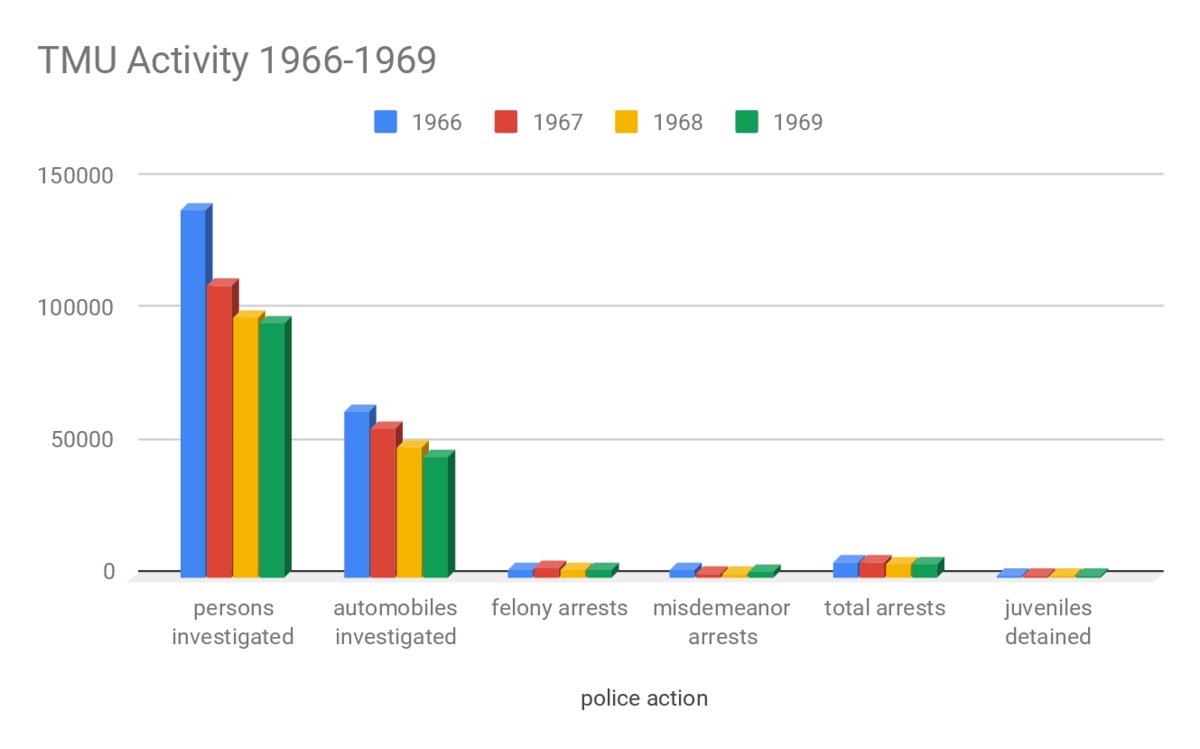

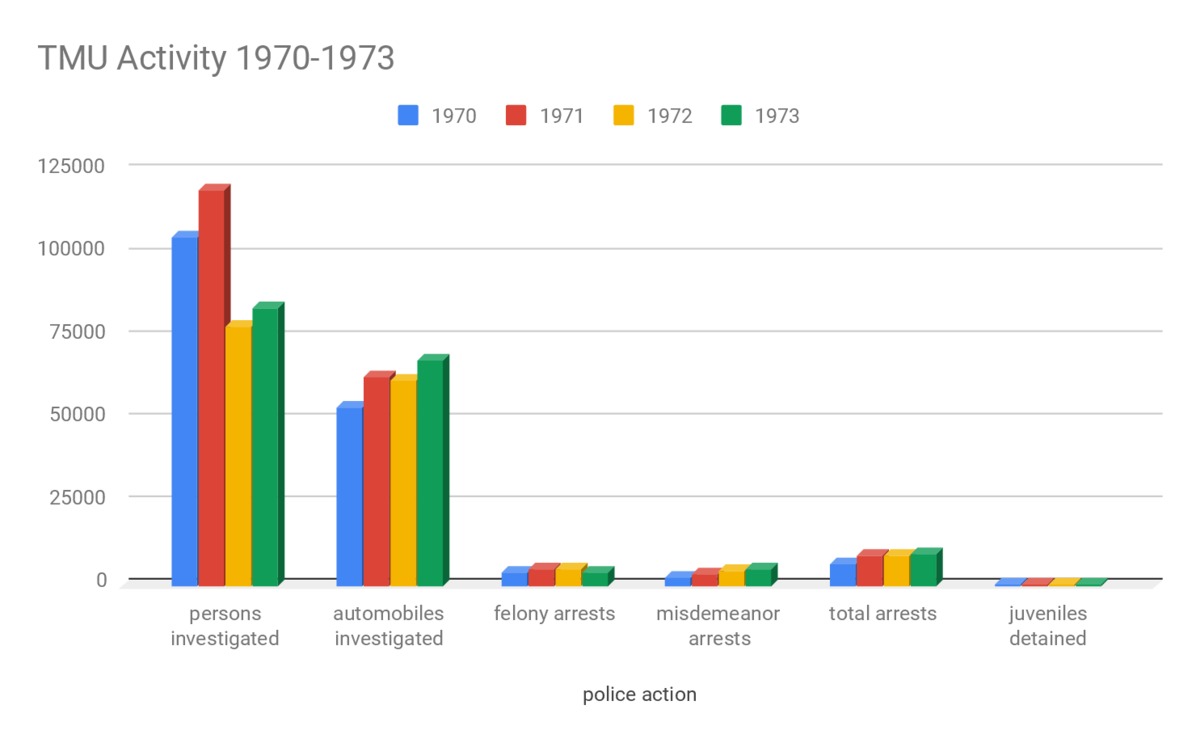

The second and third graphs below compare TMU arrests to total stops of automobiles and pedestrians between 1966 and 1973. In 1966, its first full year of operation, the TMU detained and 'investigated' around 140,000 pedestrians and pulled over about 60,000 automobiles, while making just a few thousand arrests. These patterns held for the next several years, although total stops declined somewhat before spiking again in the early 1970s. Explore these graphs to visualize a police program that pulled over and/or detained at least 100 people, on grounds of being "suspicious" in the discretionary judgment of police officers, for every one arrest made. (It is imperative to note that arrests are not evidence of crime committed, and that many arrests did not result in prosecutions or convictions).

This data provides clear evidence of over-policing and mass criminalization, indeed a sweeping violation of the civil liberties of Detroit residents. We also all know that the TMU's stop and search policies targeted the poor black neighborhoods that were at the center of the broader War on Crime--the "high crime area" in Girardin's original vision--even without hard data of the racial breakdown of stops. Furthermore, the extremely high number of motorists pulled over and detained indicates racial profiling on a mass scale--not a problem of individual officers and their prejudiced or non-prejudiced attitudes, but a clear and formal policy of the Detroit Police Department supported by Jerome Cavanagh and his liberal administration. The TMU policies were a preview of the stop-and-frisk law proposed by Cavanagh in 1965 and finally enacted in 1968.

Additionally, it is important to note that police apprehension of motorists and pedestrians without probable cause often led to incidents of police brutality and civilian allegations of police misconduct, which the DPD's internal investigation process rarely upheld.

Commissioner Girardin and Mayor Cavanagh created the TMU to deal with emergencies and massive crowds, at a time of increasing civil rights protests and growing fear of summer riots. In reality, basic street patrolling and traffic monitoring occupied the bulk of the TMU's time. Although the TMU would be hailed for its performance in several large-scale 'riot control' situations, these incidents were rare compared to their daily surveillance and criminalization of regular people going about their everyday lives.

TMU and Police Militarization

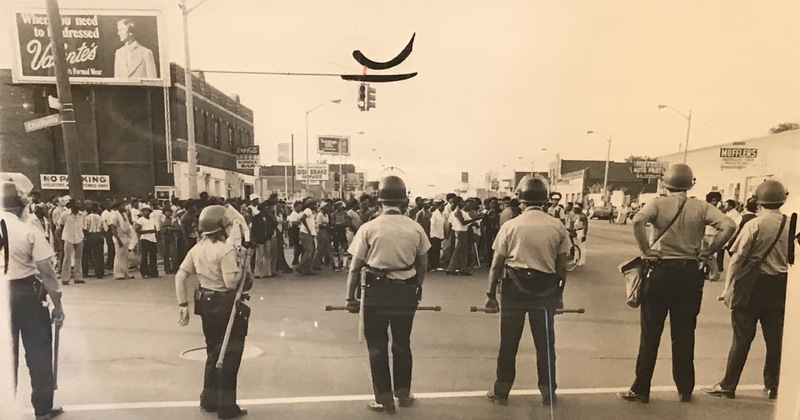

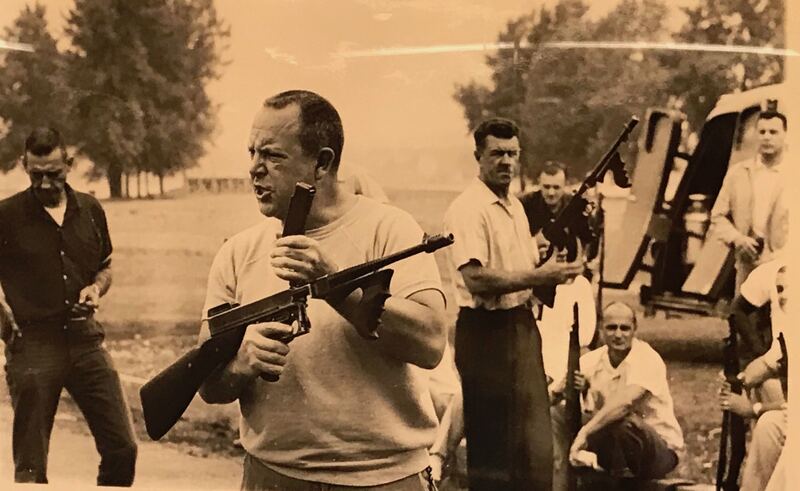

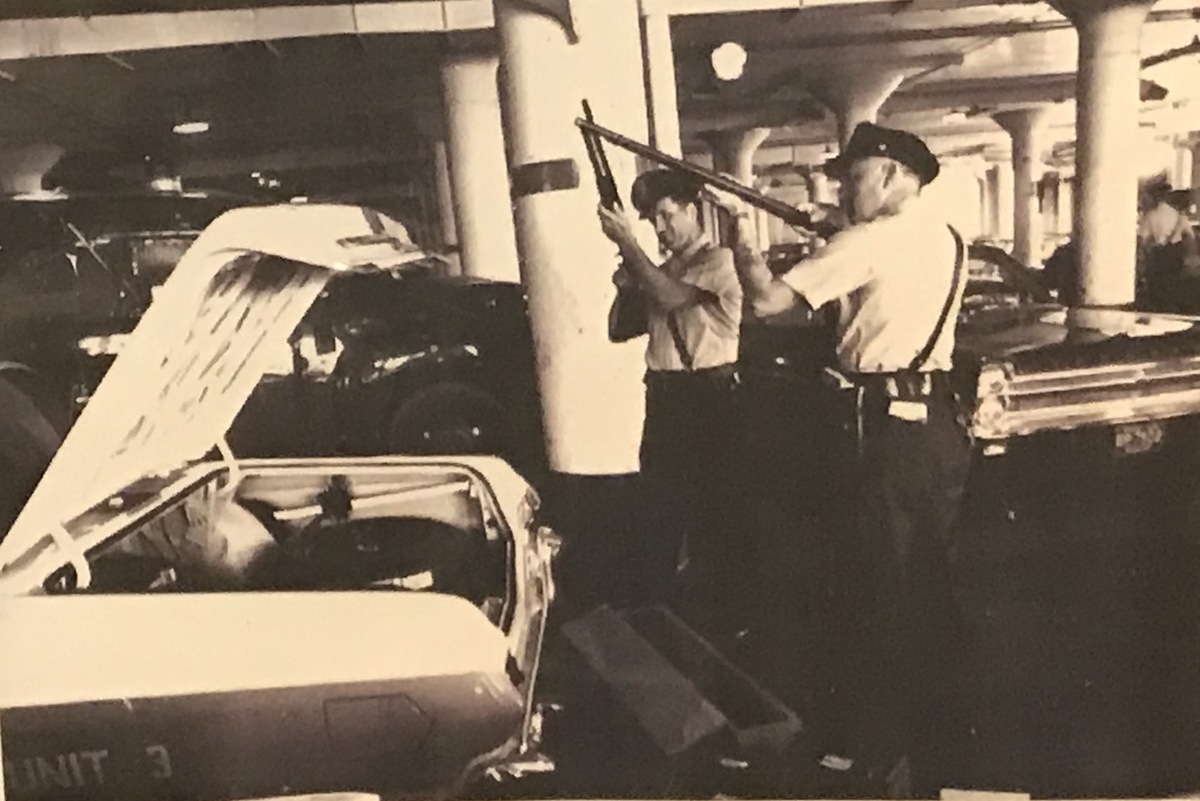

The Tactical Mobile Unit represented a trend toward increased police militarization that was happening in all major American cities during the mid-1960s, usually with funding from the federal War on Crime programs. Police departments and mayoral administrations envisioned militarized police units as "deterrent" forces that would control the public, especially as civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protests escalated. These photographs from the Detroit Police Museum reveal the military-style ethos of the TMU.

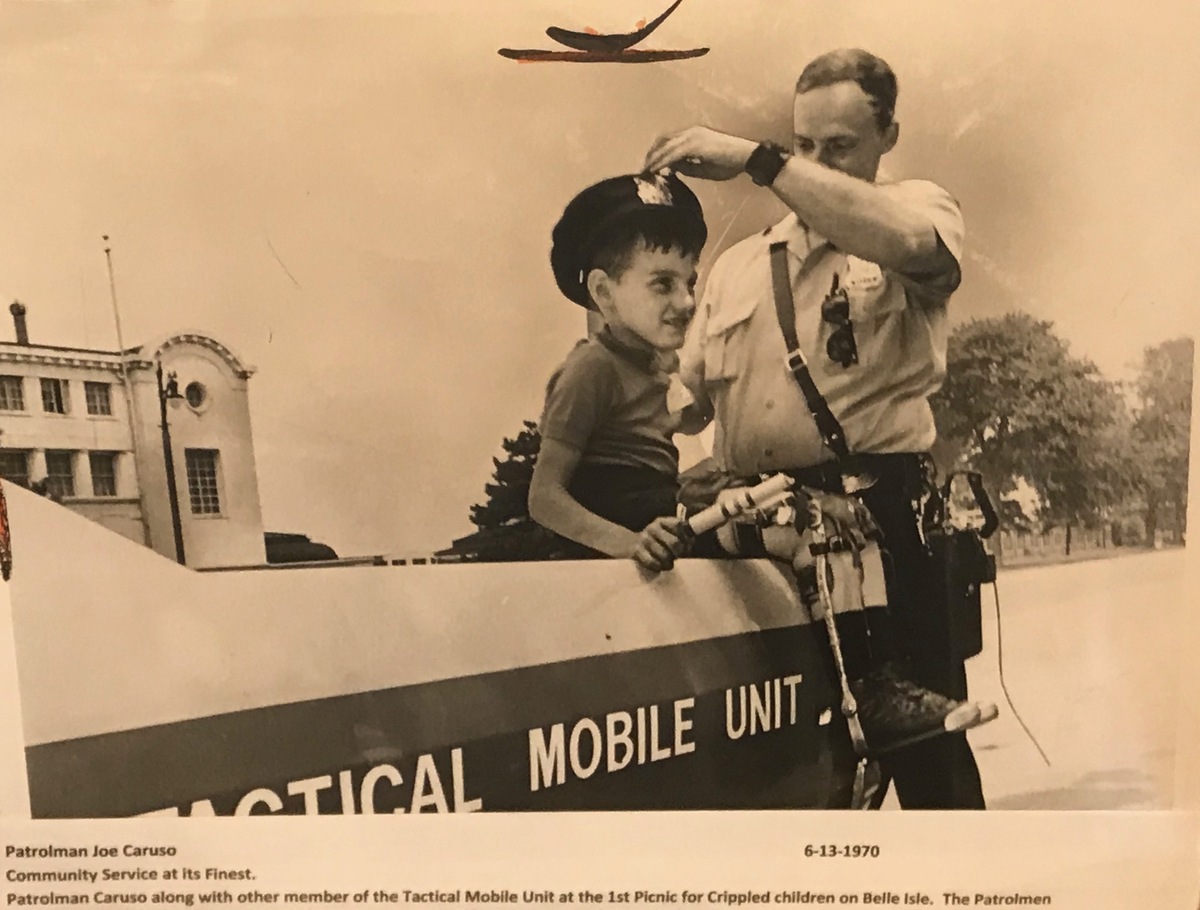

Why do police officers whose mission is to "protect and serve" the community need semi-automatic weapons to deter and control the public? Why did Detroit officers who already had department-issued handguns bring long rifles (often their personal guns) to work, and drive through black neighborhoods with the barrels hanging out of the windows? Why are these TMU officers training in military-style formation to smash civilians with the butts of their rifles? Why are all of the TMU officers in these photographs white men?

The photograph on the right and the first two in the gallery below show "elite" white officers selected for the TMU training in "riot control" on Belle Isle. The third photograph is of TMU officers in a police garage preparing their long rifles before deployment. The final photograph, from 1970, is titled "Community Service at its Finest" and was part of a public relations/damage control campaign by the Detroit Police Department, after the bitter conflicts and racial controversies of the second half of the 1960s, to emphasize its commitment to "community policing" rather than militarized occupation

Major TMU Incidents

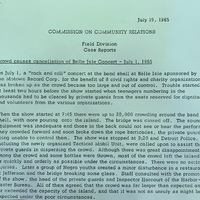

Belle Isle Concert (July 1, 1965)

On July 1, 1965, the Motown Record Corporation sponsored a concert at the Band Shell on Belle Isle in order to fundraise for various civil rights groups, including the NAACP and the Detroit Urban League. Relative to the so-called "emergency situations" the TMU was designed for, this incident was a relatively anti-climatic example of crowd control. Organizers canceled the concert around 8:00 p.m. due to a large and unruly crowd surpassing 20,000 people, white and black alike. According to the Detroit Commission on Community Relation's case report (left), some disappointed teenagers threw bottles and "a group of Negro youths created a minor disturbance." The TMU arrived to assist private guards and mounted patrolmen clear the area and ensure safety, aiding in ushering the crowd to depart Belle Isle after the concert was canceled. The DCCR reported that no attendees suffered serious injuries, and a DPD criminal investigation report listed only one minor injury despite the massive crowd.

The TMU received remarkable, indeed excessive, praise from the media for its performance on Belle Isle in July 1965. The Detroit Free Press even claimed that had the TMU not been so readily available, there could have been a riot as a result of the crowds of youth. The TMU solidified its reputation as both a crowd control unit and a l riot prevention squad, boasting rapid response time and state-of-the-art communications technology.

Kercheval Incident (August 1966)

The Detroit news media dubbed the Kercheval Incident of August 1966 a "mini-riot." It started with several African American men refusing the order of DPD officers to move off the corner. The officers called for backup, and the TMU responded quickly. A crowd of one hundred people met the TMU officers upon their arrival at the scene. As crowds grew, the TMU aided in the patrolling of the area. Armed with powerful weapons and bayonets, the TMU moved in to 'pacify' the area, undoubtedly engaging in questionable procedures. Read more about the Kercheval Incident here.

Belle Isle Love-In (April 30, 1967)

In the late 1960s, the Detroit Police Department increasingly criminalized white youth in the anti-Vietnam War movement and the counterculture, in addition to its primary focus on poor black neighborhoods. Belle Isle, the recreational island in the middle of the Detroit River, was the scene of a "Love-In" in early 1967 as thousands of young people enjoyed a weekend of carefree living and music. DPD officers were present to 'control the crowd,' and the TMU prepared for the event through its riot mobilization procedures.

The events of the Love-In took a turn when members of the crowd allegedly engaged police officers with taunting, bottle-throwing, and brick-throwing. The media did not consider the possibility of police instigation of the incident and instead labeled the events a 'battle' between riotous young people and honorable police officers. The TMU scrambled to the scene, shotguns in hand, to assist in the controlling of the crowd. As fighting escalated, officers from eight precincts were called in to assist in the battle.

After the event, the media and organizers of the event blamed radical participants of the Love-In for encouraging violence. They alleged that drinkers and thugs had infiltrated the event, especially members of a motorcycle gang, leading to the massive brawl with police.

Detroit Uprising (July 1967)

The TMU's role in the July 1967 Uprising was similar to its role in the Kercheval Incident a year prior. The DPD directed units to monitor the conflict areas, round up alleged snipers and looters, and control crowds setting fires. The officers of the TMU struck fear into the public, roaming the streets with heavy-duty artillery and massive demonstrations of force. Read more about the 1967 Uprising here.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Museum, Detroit, MI

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan

Jerome Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Michigan Chronicle

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (2016)