2. Fatalities and Victims

The official death total of the Detroit "Riot" is 43 people--33 African Americans and 10 white people. The interactive map on this page displays 47 fatalities, including four additional African American residents, based on our research findings into the Detroit Uprising of late July/early August 1967. This is still probably an undercount.

Law enforcement agencies shot and killed at least 35 people. All but two were unarmed. Thirty were African American, including almost everyone shot deliberately. Four of the five white people killed by law enforcement were shot accidentally, although in some cases through extreme indiscipline in violation of orders of engagement.

The Detroit Police Department killed the most people and operated under orders to "use discretion" to shoot looters. The National Guard killed the second largest group and deployed with initial orders to "shoot any person seen looting" and to shoot looters "if necessary." The U.S. Army deployed later with orders to "use the minimum force necessary" and killed only one person. The National Guard came under the same orders as the Army at this time and did not comply.

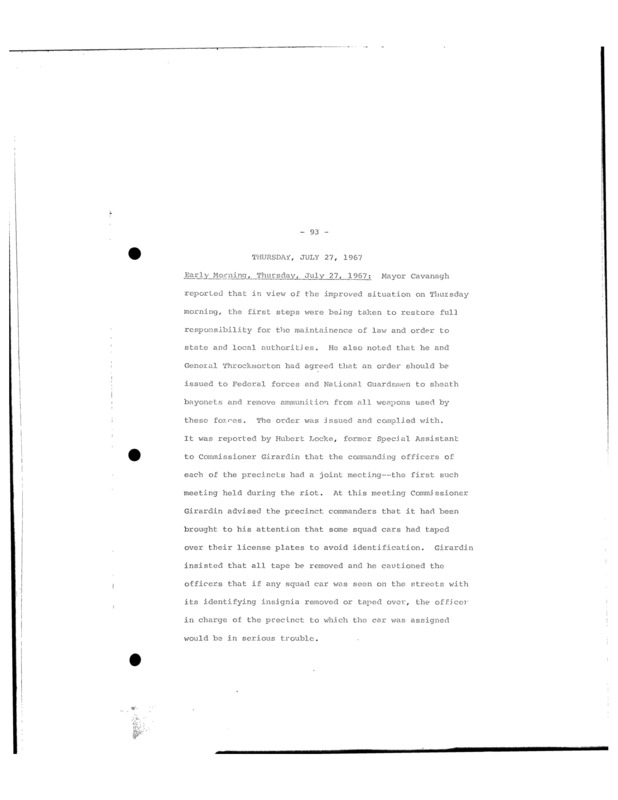

Many of the fatal shootings (and non-fatal shootings) by DPD officers appeared questionable under the police department's "Use of Firearms" policy (right), which had been revised in 1962 and remained operative during the 1967 Uprising. The policy instructed officers to discharge their weapons only in "extreme cases" and restricted deadly force "to apprehend or prevent escape of a known felon . . . if the perpetrator cannot be apprehended by any other means." The DPD policy further stated that "the officer should not fire upon a person who is called upon to halt upon mere suspicion and who, without resisting, simply runs away to avoid arrest. Neither should the officer fire at a person who is running away to avoid a minor arrest." Instead of conducting thorough investigations of DPD officers who killed fleeing civilians suspected of low-level property crimes during the 1967 Uprising, the police department and the Wayne County prosecutor presumed all of these shootings to be justified. However, the DPD significantly liberalized its "Use of Firearms" policy on Sept. 1, 1967, removing almost all of the above language and specifically authorizing the shooting of burglary and arson suspects, which can only be interpreted as a recognition that the discretionary use of deadly force by DPD officers was stretching the parameters or in actual violation of the manual and that get-tough policing in Detroit's black neighborhoods required clearer encouragement to shoot.

There is considerable evidence indicating a pattern of coverups and framing of victims in the homicides by DPD officers and National Guardsmen, followed by non-impartial investigations by the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor. In our project's assessment, at least 21 of the 35 fatal shootings attributed to law enforcement are questionable or suspicious, in particular because eyewitness testimony and/or forensic evidence contradicted the official accounts. These circumstances are examined in detail on the following "Remembering the Casualties" page. The Wayne County Prosecutor, William Cahalan (right), exonerated law enforcement in every questionable case except for three in the Algiers Motel Incident when the DPD coverup unraveled.

The fatalities in the interactive map below are located in the city's racial geography (dark blue = all-black neighborhoods, dark green = the most segregated white areas). Hover over the dots to view the incident description and source. Note that in a majority of these cases, 'what actually happened' is deeply contested. The incident descriptions and cause of death in this map differs in many cases from initial media reports, which generally accepted law enforcement accounts at face value and often classified deceased African Americans as "looters" and "snipers," when the real story was often more ambiguous or directly contradictory. Analysis of these patterns is below the map. The colors indicate:

- Red (22 people) = Killed by Detroit Police Department officer(s)

- Black (11 people) = Killed by Michigan National Guardsmen

- Yellow (7 people) = Killed by civilian

- Grey (5 people) = Killed by unknown (usually arson)

- Purple (1 person) = Killed by Army trooper

- Blue (1 person) = Killed by Michigan State Police trooper

Fatalities during the 1967 Detroit Uprising (Racial Geography Map)

Key Findings

- 21 of the 35 fatal shootings attributed to law enforcement are questionable or suspicious, with witness testimony and/or forensic evidence indicating likely coverups by the police officers and National Guardsmen on the scene. Full details here.

- 33 of the 35 people shot and killed by law enforcement agencies were unarmed.

- 30 of the 35 people shot and killed by law enforcement agencies were African American. All but one of the white people were shot accidentally, most by the Michigan National Guard.

- 15 of the 22 people shot and killed by DPD officers were unarmed African American males alleged to be "looters." A majority were fleeing and shot in the back for what was at most a property theft offense. The DPD orders were unclear and unwritten but appeared to include authorization to "use discretion" in shooting looters. The Wayne County prosecutor ruled all shootings of alleged looters to be justifiable homicides, based on the "fleeing felon" rule that officers could use deadly force against the felony of "breaking and entering."

- 7 of the DPD homicides classified as fleeing 'looters' appear suspicious, based on witness testimony and forensic evidence. In several incidents, DPD officers killed bystanders and onlookers and then classified them as looting suspects in apparent coverups. In three others--Ronald Evans, William Jones, and William Dalton--DPD officers killed African American males who were already in custody and claimed that they had been trying to escape, but witness accounts insisted that they had been murdered. (See the "Remembering the Casualties" page for details).

- Three fatalities involved unarmed African American males shot for alleged looting by store owners or private guards, all ruled justified.

- DPD officers murdered three African American male teenagers in the Algiers Motel Incident and did face criminal charges or investigations, but none was convicted.

- Most of the 11 homicides by National Guardsmen involved unarmed African Americans who posed no threat. In several incidents, National Guardsmen killed clearly innocent people by firing wildly into buildings and moving cars, including a 4-year-old girl, middle-aged men on their way to work, and a 26-year-old Guardsman. The National Guard deployed with orders "to shoot any person seen looting." No cases involving National Guardsmen resulted in criminal charges, even when Guardsmen clearly sought to cover up what actually happened and frame the victims as snipers and looters. This includes the Albert Robinson homicide, as multiple witnesses insisted that National Guardsmen had tortured an innocent Black man and then shot and killed him while he was helpless on the ground.

- Official government and newspaper compilations do not include any homicides by the Michigan State Police, but our research has uncovered one (Mike Williams), and there may well be others.

- Of the four white law enforcement officials or firefighters who died, two were shot accidentally by National Guardsmen, one was shot by a DPD officer's gun in a confusing sequence of events, and one died fighting a fire. In other words, despite intense hype and panic, no "snipers" killed any law enforcement officers or military troops.

- Of the six white civilians who died, two were shot by DPD officers as alleged looters, one was almost certainly killed by National Guard gunfire but blamed on a sniper, one was shot by the National Guardsmen and framed as a sniper, one was struck by a bullet from an unknown source, and one was a store owner beaten to death by looters.

Please visit the "Remembering the Casualties" page for detailed accounts of all 47 of these fatalities.

The gallery below includes analysis and details of a majority of these homicides conducted by the Kerner Commission in its investigation of the civil disorder in Detroit. These reports are more thorough, and more skeptical of the official version, than the DPD Homicide Bureau document (above right), but they are certainly not definitive. The fatality reports are also interspersed throughout a more detailed chronology of the days in question.

The Political Category of "Justifiable Homicides"

The Wayne County Prosecutor's Office, led by William Cahalan, applied the finding of "justifiable" homicide to every fatality of an African American resident of Detroit during the 1967 Uprising, except for the eventual decision to prosecute the officers involved in the Algiers Motel Incident once overwhelming evidence emerged. The finding of "justifiable" homicide, when applied so broadly to cover so many different types of incidents, deserves to be analyzed as a clearly political and indeed racially motivated application of the law rather than a product of careful investigation and neutral principles. To reinforce this point, the DPD and prosecutor's office often over-charged civilians involved in murky incidents that resulted in the deaths of law enforcement officers and military troops, including three young white men initially charged with assault with intent to murder for the death of a National Guardsman who was accidentially shot by other members of his unit, and a 20-year-old Black male charged with first-degree murder when a police officer was shot by another officer's gun in a 'scuffle' that a witness insisted began with the officers beating him.

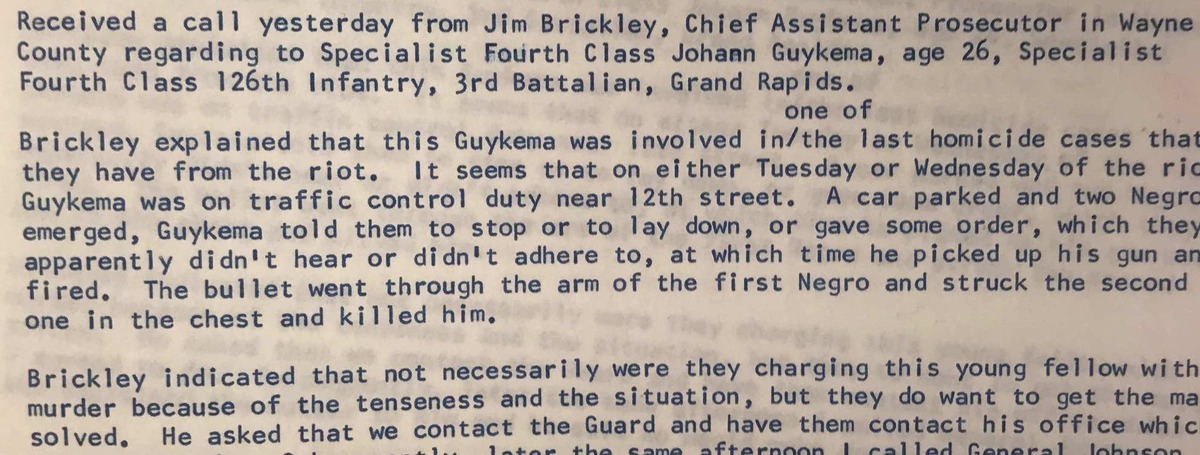

George Talbert: In the document excerpted above, the legal counsel to Governor George Romney is reporting on the explanation from the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office that National Guardsman Johann Guykema will not be charged in the killing of an unnamed "first Negro" (George Talbert, 20 years old) even though he fired at two unarmed civilians after allegedly yelling at them to lay on the ground from across the street. Guykema received the benefit of the doubt "because of the tenseness and the situation," even though his decision to open fire on unarmed civilians violated National Guard orders for rules of engagement. Multiple witnesses stated that Guykema fired without warning, and he also then lied to investigators and claimed that Talbert had charged and threatened to kill him. Talbert, who died of his injuries more than a week later, told his family he thought he had been shot by a sniper and clearly never even saw Guykema. The prosecutor's determination did not simply exonerate a National Guardsman for an accidental death in a chaotic situation; it involved actively ignoring the clear evidence that the National Guardsmen present refused to allow residents to take Talbert to the hospital, concocted a cover story to frame the victim, and falsely reported what had happened to the DPD Homicide Bureau.

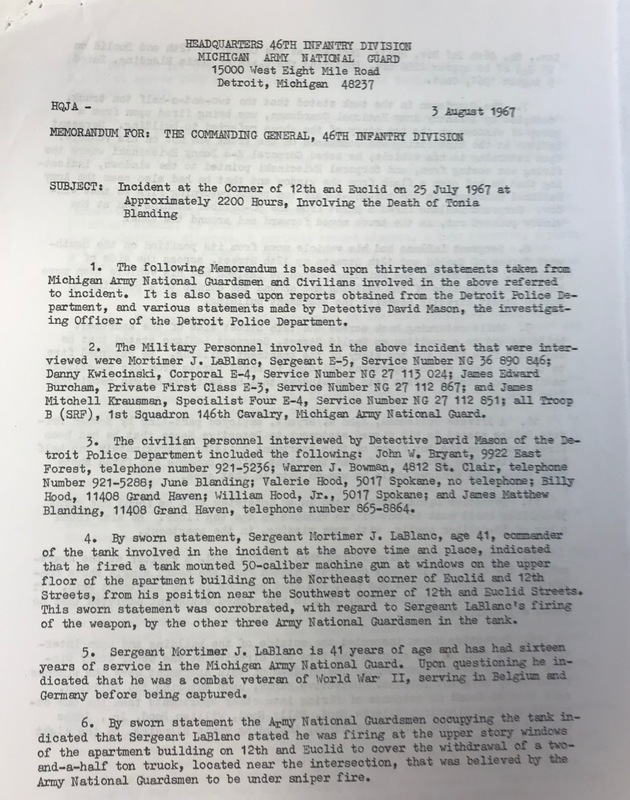

Tonia Blanding: In another tragic episode at 1:20 a.m. on July 25, Sergeant Mortimer J. LaBlanc of the Michigan National Guard fired the 50-caliber machine gun mounted on his tank into an upper-floor apartment on the corner of 12th Street and Euclid, killing 4-year-old Tonia Blanding. The National Guard investigation of the "incident involving the death of Tonia Blanding" placed blame for the decision to fire a machine gun into a residential building on the imagined sniper fire that "was believed by the Army National Guardsmen" to be threatening a truck that needed to withdraw from the intersection. The report transfoms this residential intersection into a war zone in order to justify an operational failure--firing wildly into an occupied residential building--that might well have violated international 'rules of engagement' had it happened in an actual war situation. National Guardsmen fired wildly at snipers throughout the Detroit Uprising, a context that the official investigation never addressed (although the Kerner Commission strongly criticized the overreaction). The Detroit Police Department's Homicide Bureau joined the Michigan National Guard in shifting blame for the death of Tonia Blanding onto the residents of the building and her immediate family by asserting that either her father or her uncle lit a cigarette, an alleged violation of shouted orders for residents to keep their apartments completely dark, and that this action caused the National Guard unit to open fire. The death of Tonia Blanding, a terrible tragedy, was also legally a "justifiable" homicide.

A Pattern of Whitewashing Homicide Investigations. The Wayne County Prosecutor declared almost all law enforcement homicides that occurred during the Uprising to be "justifiable" not simply because of the special circumstances of a chaotic civil insurrection, but because the prosecutor almost always declared police homicides to be "justifiable" regardless of the circumstances. Only three of more than 200 on-duty police homicides resulted in murder prosecutions during the 1957-1973 time period covered in this Detroit Under Fire exhibit, and two of those were at the Algiers Motel. As the next "Remembering the Casualties" page covers in more detail, the political and racial category of "justifiable" homicides during the Detroit Uprising included at least three young Black males who were already in police custody when shot while allegedly trying to escape, even though multiple witnesses insisted they had been murdered by white officers; a Black man shot and killed while lying on the ground by National Guardsmen who framed him; and more than a dozen other incidents where forensic evidence and witness accounts strongly indicate coverups by the law enforcement officers on the scene.

Sources for this Page:

Note: The book Nightmare in Detroit, by investigative journalists Van Gordon Sauter and Burleigh Hines, was an invaluable resource in reassessing the initial incident reports in the Detroit newspapers. The "43 Who Died" series in the Detroit Free Press (Sept. 3, 1967) also provided a more complex portrait than the initial police-shaped coverage in the Free Press and the Detroit News, including the News's widely circulated "A Time of Tragedy" report (Aug. 11, 1967).

Kerner Commission Investigative Staff, "Detroit, Michigan: Description of Area and Chronology of Disorder of July 23-August 2, 1967," Folder 001346-008-0104, Civil Rights during the Johnson Administration, 1963-1969, Part V: Records of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission), Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin Texas (ProQuest History Vault)

"Incidents Reported at the Time of the Detroit Riot to Congressman John Conyers and the Detroit Branch of the NAACP," n.d. [August 1967], Folder: Civil Liberties - Blacks - Michigan - Detroit - 1967 Rebellion, Subject Vertical Files, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Department, "Deaths Due to Civil Disorder," July 27, 1967, Box 319, Folder Detroit Riot, George Romney Paprs, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Michigan State Police, "Racial Disturbances-Detroit," July 24, 1967, Box 319, Folder: Detroit Riot General, George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

"The 43 Who Died," Detroit Free Press, Sept. 3, 1967

"A Time of Tragedy," The Detroit News, August 11, 1967

Van Gordon Sauter and Burleigh Hines, Nightmare in Detroit: A Rebellion and its Victims (Henry Regnery Company: Chicago, 1968)