Kerner Commission

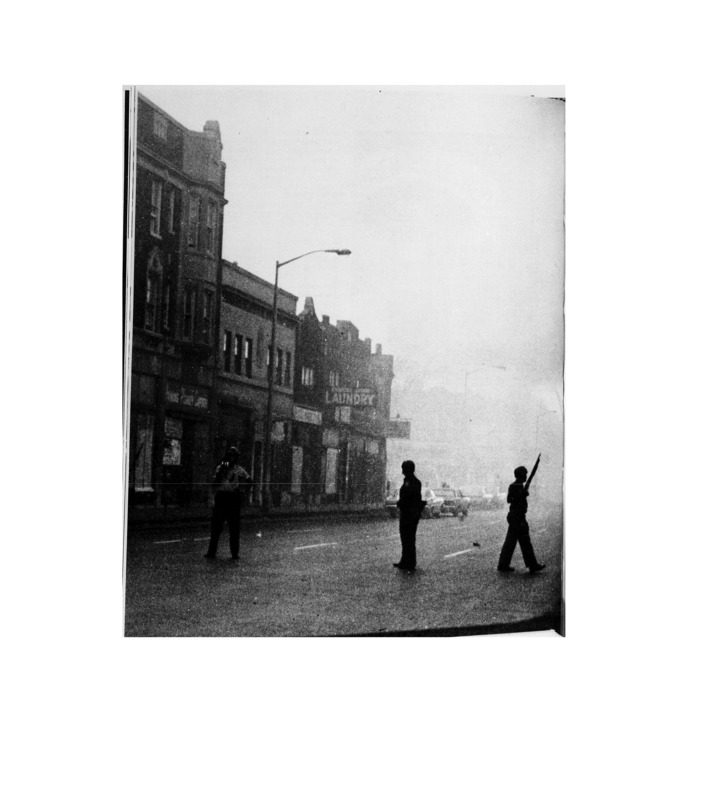

President Lyndon Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Violence and Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission, to examine the causes of the racial unrest in Detroit, Newark, and other American cities. The president primarily wanted an investigation of "the rioters" and what had caused the explosion of racial violence. He expected that the Kerner Commission would find evidence that a black militant conspiracy had instigated the violence, which it did not. Instead the Kerner Report, released in March 1968, placed the fundamental blame for the urban crisis on white institutions and white racism, exacerbated by police brutality.

In its investigation, the Kerner Commission visited Detroit and a number of other cities that had experienced racial unrest, interviewing a broad range of actors from mayors and police chiefs to community activists and black militants. The inquiry focused on the three questions that President Johnson had placed on its agenda:

- What happened?

- Why did it happen?

- What can be done to prevent it from happening again?

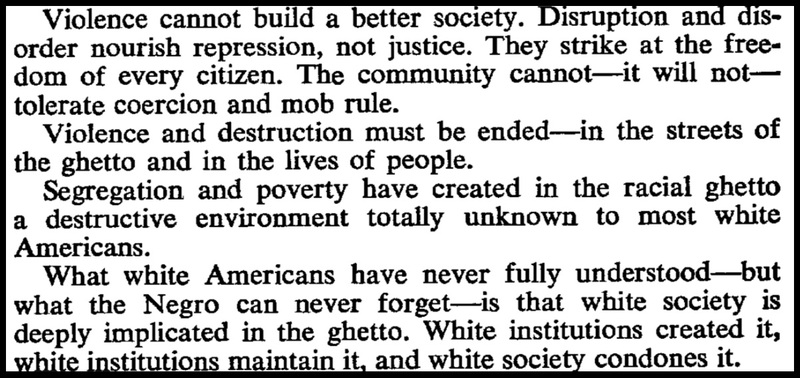

The Kerner Report was the most hard-hitting indictment of white racism and racial segregation produced by any American government agency or commission up to that point. The opening summary (at right) made clear that "mob rule" would not be tolerated but placed the primary responsibility for the civil unrest on white Americans and white institutions. The section on "Why Did It Happen?" identified racial segregation and discrimination in housing, education, and employment that created hopelessness and despair in the inner city ghettoes: "White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it." The Kerner Commission concluded:

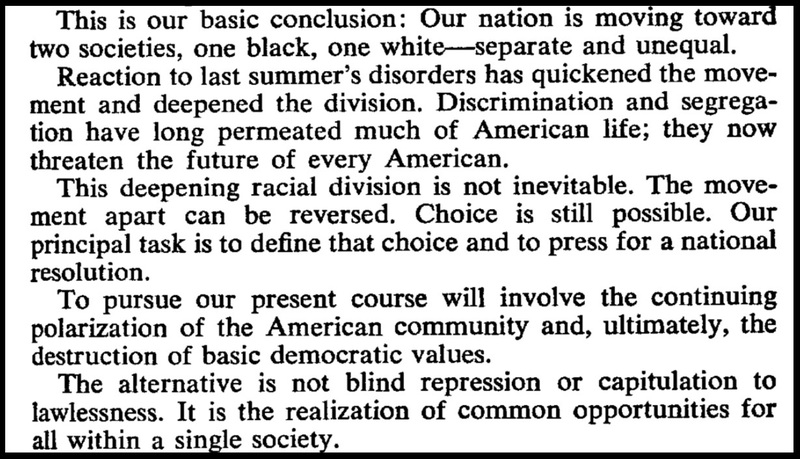

The Kerner Report also issued a stark warning: "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white--separate and unequal." The situation had become even worse since the summer of 1967, because of white backlash against the civil rights movement and continued white flight to the suburbs. The Kerner Commission presented Americans with three alternatives:

- "We can maintain present policies, . . . and the inadequate and failing effort to achieve an integrated society"

- "We can adopt a policy of "enrichment" aimed at improving dramatically the quality of ghetto life while abandoning integration as a goal" [the report identified this as the black power approach]

- "We can pursue integration by combining ghetto 'enrichment' with policies which will encourage Negro movement out of central city areas."

The Kerner Commission strongly endorsed the third option, enrichment through massive resources for urban centers combined with racial integration as an explicit policy goal. The report warned that the first option, staying the course, would lead to more "violent protest" by African Americans in the inner city and more racial polarization thoughout the nation. The commission sounded this as an alarm: "to continue present policies is to make permanent the division of our country into two societies; one, largely Negro and poor, located in the central cities; the other, predominantly white and affluent, located in the suburbs and outlying areas." The report argued that the second option, the black power or 'separate but equal' appoach, would also fail because white society would never share resources equally and racial polarization would accelerate.

The Kerner Report declared that only "a commitment to national action--compassionate, massive, and sustained," with racial integration and equal distribution of resources as the primary goals, would resolve the urban crisis.

Read the introductory sections of the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders in the gallery below.

Kerner Commission on Police Brutality

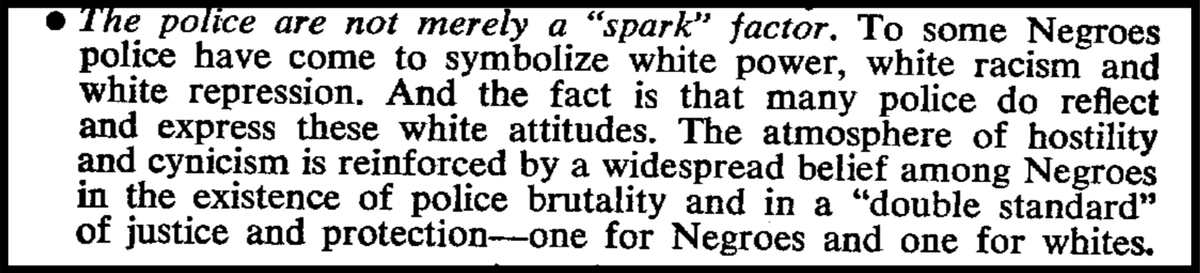

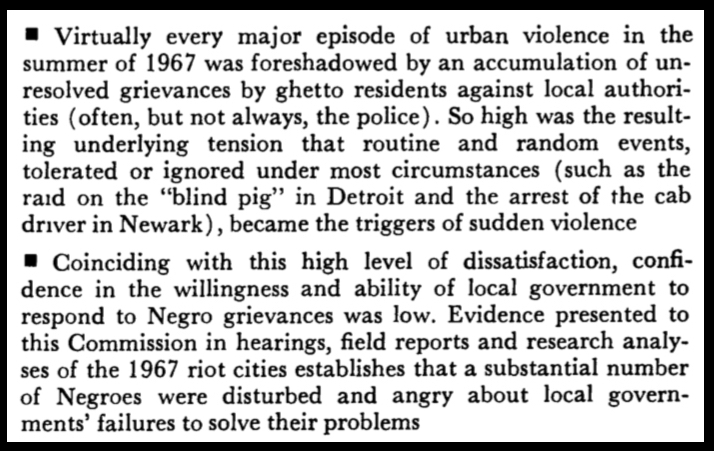

The Kerner Report emphasized the role of the police in two ways--as the immediate triggers of almost every episode of urban civil unrest, and as a broader institution of "white power, white racism, and white oppression"--at least in the eyes of "some Negroes" (see above).

It is worth noting that in its summary and introduction, the Kerner Commission offered a sweeping assessment of the role of white racism and segregationist white institutions in housing, education, and employment as a basic fact of American history and contemporary social conditions. When it came to the police, however, the Kerner Report took a more indirect route, observing that there was a "widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a 'double standard' of justice and protection."

In reality, police brutality and racial inequality in law enforcement and in the criminal justice system were structural and pervasive in the urban North and throughout the United States, not just something that African Americans 'felt' and 'believed.' But the Kerner Commission was just as interested in documenting the criminality and disorder of young black "rioters," and its sections on police brutality lacked the moral clarity of its other calls for social reform and social justice. The summary of the Kerner Report included a long list of specific proposals for reforming housing, employment, education, and the social welfare system--but nothing tangible about transforming the role of the police in urban African American communities.

Chapter 11 of the Kerner Report did address "The Police and the Community" at length (gallery, below left). This section portrayed the police as caught between the demands for tough law enforcement by the white majority and charges by black militants that they operated as "agents of repression." Again, the Kerner Commission presented the latter view as something that African Americans perceived and believed, rather than as a historical fact:

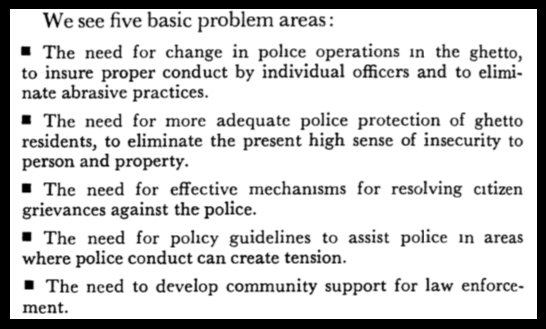

The Kerner Commission stated that it was impossible to know how often police abused their "discretion in the use of force." The report did acknowledge that "indiscriminate stops and searches" and harassment of African Americans on the street, especially groups of youth, was common practice and had increased with formal stop-and-frisk tactics and special "aggressive preventive patrol" units (such as the DPD's Tactical Mobile Unit).

The Kerner Report recommended that police departments eliminate brutality and misconduct through clear use-of-force guidelines, provide better protection from crime for ghetto residents, hire and promote more African American officers, and create mechanisms to resolve citizen complaints fairly (see right). Its investigation found that in Detroit, and in every other city, "no real sanctions are imposed on offending officers." In the end, the Kerner Report sought to split the difference, declining to endorse civilian review of police misconduct but also recognizing that police departments could not adequately investigate their own officers. The commission recommended that a separate, "external" municipal agency investigate complaints against the police and have the power to impose discipline.

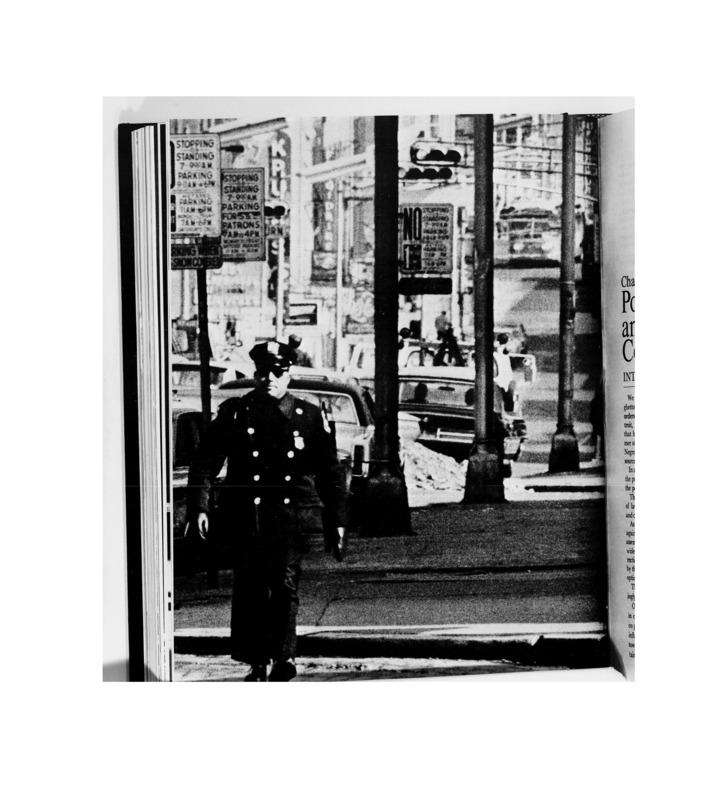

Chapter 12 of the Kerner Report examined the actions of police in controlling the civil disorders themselves (below, second from left). The "Use of Force" section of this chapter asked whether it was really justified to use deadly force against looters: "Are bullets the correct response to offenses of this sort?" The Kerner Report also criticized the police overreaction to alleged sniper fire, which "was highly exaggerated." The Kerner Commission recommended "minimum use of force by police" and recommended tear gas and other "nonlethal" weapons in riot control situations, rather than shooting people.

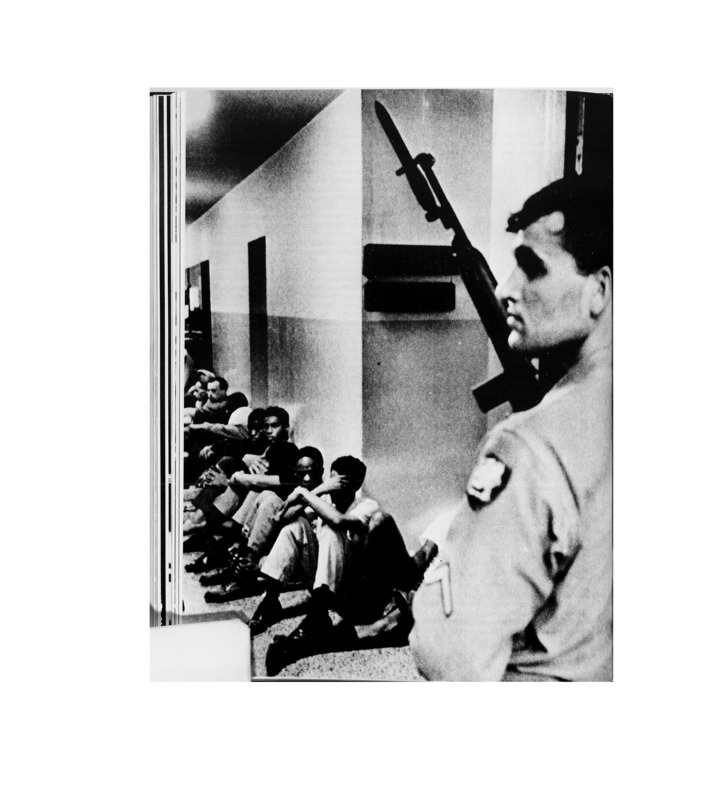

Chapter 13, "Administration of Justice in Emergency Conditions," critiqued the courts for "assembly line justice," including excessive bail and indefinite detention, after the police made indiscriminate mass arrests as a riot control strategy. According to the Kerner Commission, this built on existing unfar processes in local criminal justice systems, especially cash bail policies that kept many poor and black people confined for long periods of time before trial. The report also pointed out that the Detroit Police Department had arrested dozens of people for inciting riot or sniping "with intent to commit murder," but almost all charges had been dismissed for lack of evidence. Many "innocent bystanders" and "minor curfew violators" also had been arrested, inflaming racial tensions without furthering the interests of justice.

Read the Kerner Commission's examination of the role of police and the broader criminal justice system in urban areas generally, and during the civil unrest specifically, in the gallery below.

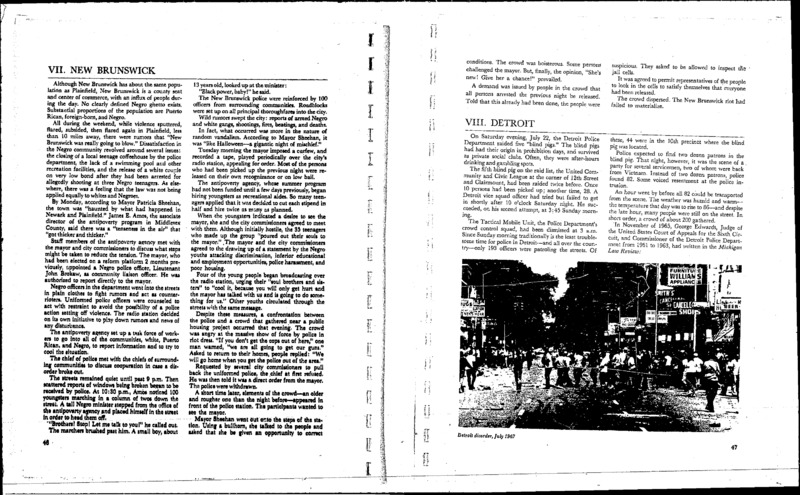

Kerner Report on Detroit

The Kerner Commission's report included a "profile of disorder" on each of the eight cities that experienced major unrest in 1967, including Detroit. The Detroit profile (gallery, below left) portrayed the July 23 raid on the blind pig as the spark in an African American neighborhood already frustrated by frequent incidents of police brutality. The Kerner Report also stated that the DPD's Citizens Complaint Bureau was ineffective at best (for more, see the Citizen Complaint Bureau page in the previous section).

The report portrayed 12th Street as a community that suffered from overpolicing and underpolicing at the same time. Almost four-fifths of residents surveyed believed that the police department failed to respond in a timely manner when asked for assistance. Fully 93% expressed the desire to move out of the neighborhood. Recent urban renewal programs had contributed to the overcrowding of the 12th Street area by displacing poor black residents of other parts of the city, and as they moved in almost all white residents moved out, leaving behind only the white-owned stores that often exploited their customers.

The Detroit "profile of disorder" recounted the looting, arson, fatalities, and occupation of the city already described in previous pages of this section, which used the Kerner Commission's investigative files as part of their evidence base. The published report described the details of a number of questionable shootings by Detroit Police Department officers and National Guardsmen, without explicitly second-guessing the prosecutor's decision to find all of them to be justified (except for the Algiers Motel murders). The Kerner Commission's assessment of what happened in Detroit is nevertheless a sobering indictment of the operational failures and excessive force deployed by the DPD and the National Guard.

Chapter 2, "Patterns of Disorder," found that the "typical rioter" was not a "hoodlum" or "criminal" but rather an unemployed or underemployed African American teenager or young adult who felt alienated from white society and from traditional middle-class civil rights organizations (gallery, second from left). There was no organized black power conspiracy but rather spontaneous and collective actions by African American youth who "attacked white authority and property" because they wanted and demanded the full rights of American citizenship. These findings reinforced the Detroit Urban League's survey and portrayed the actions of the "rioter" as clearly political, if disorganized, and connected to broader racial inequalities in housing, education, employment, and policing.

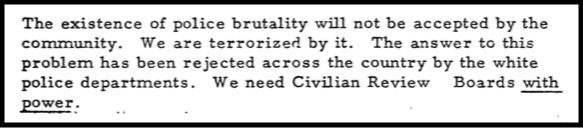

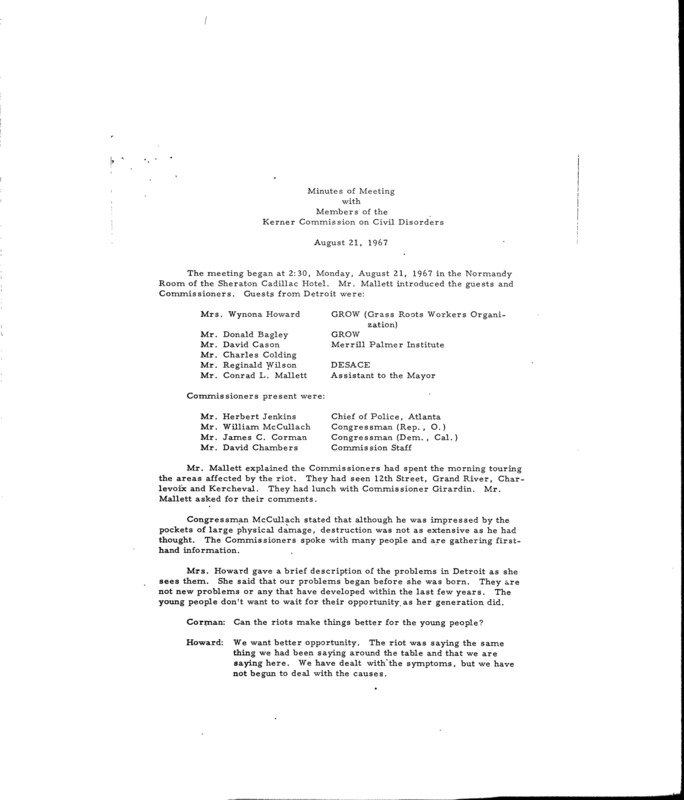

The Kerner Commission investigators also visited Detroit and interviewed African American residents and community activists as part of their inquiry into the causes of the racial unrest. In one such meeting, young African Americans in the Grass Roots Workers Organization told investigators the following (gallery, second from right):

- "We want better opportunity"

- "We must attack what makes ghettos."

- "Negroes are systematically excluded from the mainstream of life."

- "Is there a bigger insult than going to Chrysler's and knowing that you are qualified and still are not getting the job?"

- "Racists in Detroit have the finest power structure in the country, and they are more skilled [at racism] than in the South."

- "The riots are completely the responsibility of the white society."

- "You are going to get your foot off my back or I am going to break your leg."

The activists specifically addressed the problem of police brutality:

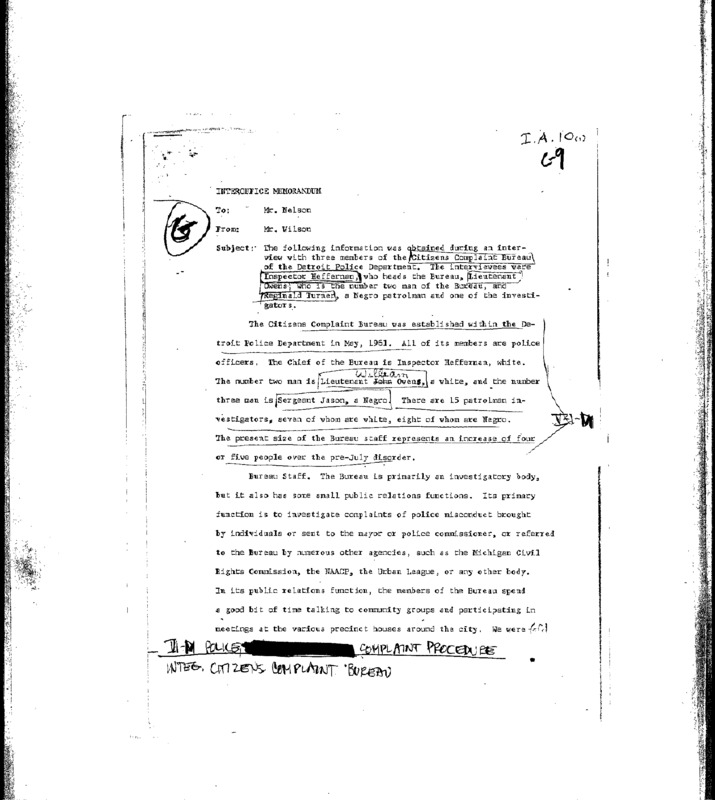

The Kerner Commission also interviewed three DPD officers who served as investigators for the internal Citizens Complaint Bureau (gallery, far right). The interview confirmed that the CCB cleared accused officers in the overwhelming majority of cases and that when assessing the competing accounts of an officer and a civilian, the process assumed the officer was in the right. All of the investigators conceded that the penalties for police misconduct were very lenient, generally either a letter of reprimant or a requirement to write a letter of apology to the civilian. The white officer in charge of the CCB also prevented the Kerner Commission field staff from interviewing any of its African American investigators separately.

The CCB reported having received a deluge of complaints from African Americans after the July disturbance. Despite Mayor Cavanagh's promise of a thorough investigation of each complaint, the three CCB officers told the Kerner Commission that this would not happen. First, many civilian complaints did not identify the individual police officer, largely because most members of the DPD force removed their badges during the riot to disguise their identities. Second, the CCB anticipated leniency for "riot related misconduct" because of the "pressures under which the officers were working."

The police investigators' description of the inadequacy of the Citizens Complaint Bureau, and the lack of support for its effort from the DPD hierarchy, helped encourage the Kerner Commission to recommend external review of police brutality and misconduct complaints (above). Read more about the Kerner Commission's investigation of Detroit and its police department in the gallery below.

Sources:

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, March 1968 (Washington: GPO, 1968), National Criminal Justice Reference Service

Jerome P. Cavanagh Photographs and Other Material, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Civil Rights during the Johnson Administration, 1963-1969, Part V: Records of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission), Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas