4. Visualizing Detroit '67

This section displays historical photographs from the "Riots and Protests. Detroit 1967" collection at the Michigan State Archives, followed by a final StoryMap produced by the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab and designed to provide a very different perspective from the official history of the state of Michigan. The two main categories of photographs in the Michigan State Archives are laudatory images of mostly white Army troopers and exclusively white National Guardsmen in the military occupation and aerial images of building rubble and property damage in the so-called "riot zone."

Archival collections reflect the political agendas of the institutions that contain them. Archivists choose to document some perspectives and silence others, to gather materials from some historical actors and not from other participants in the same events. Most of the photographs at the Michigan State Archives came from the public relations division of the Michigan National Guard, which killed ten people and did not perform impressively in its occupation of the city, or from media images transferred from the Michigan Historical Commission, charged with official commemorations of state landmarks.

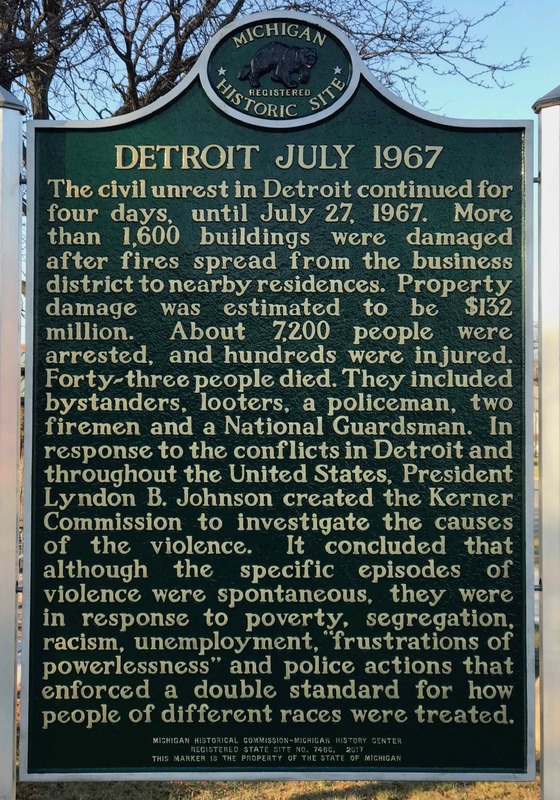

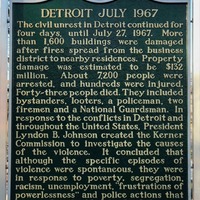

The Michigan Historical Commission did not officially commemorate the "civil unrest" in Detroit's summer of 1967 until the fiftieth-anniversary marker (image on right), erected in 2017 in Gordon Park at the intersection of Clairmount and Rosa Parks Blvd. (formerly 12th Street). The marker begins by emphasizing the property damage ($132 million) before moving on to arrests, injuries, and fatalities. The marker equates the individually specified deaths of two firefighters, a police officer, and a National Guardsman with the thirty-nine (an undercount) civilian residents of Detroit who are reduced to the categories of "bystanders" and "looters."

The belated historical marker does, importantly, address the Kerner Commission's verdict that the events of Detroit 1967 resulted from a long history of "poverty, segregation, racism, unemployment . . . and police actions that enforced a double standard" and deprived African Americans of equal opportunity through official polices of racial discrimination.

"A Double Standard"

Very few of the historical photographs collected in the Michigan State Archives--displayed below and on the next two pages--seek to tell the contested history of the Detroit Riot/Rebellion/Uprising from the perspective of the African American residents of the occupied sections of the city, and of the neighborhoods that had long suffered and continued to suffer from police brutality, racial segregation, and unequal opportunity in the Jim Crow North.

A photograph freezes time and space into a particular moment, which can appear to be a snapshot of something that 'really happened,' but also always obscures the complexity of the events in question, silences alternative perspectives, and obscures the historical conditions that led to this moment in time.

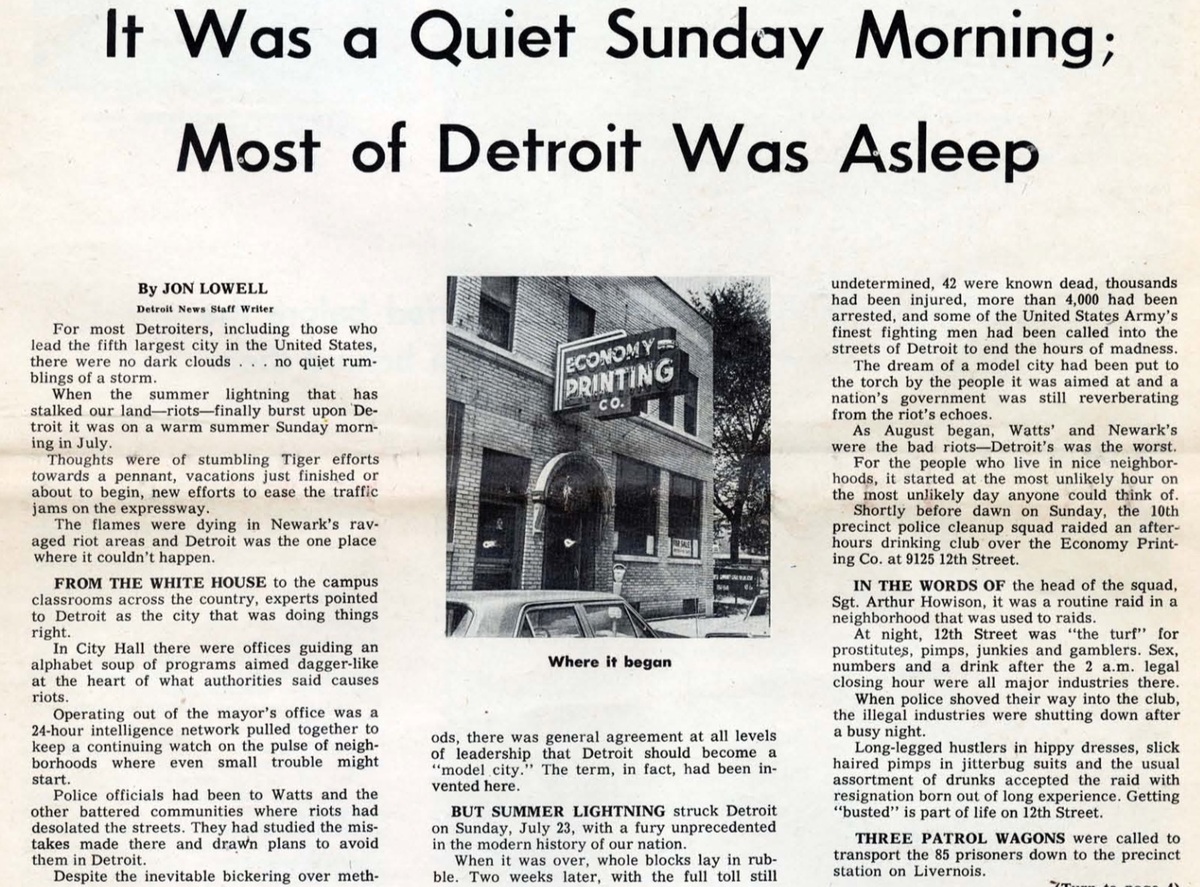

For example, the Detroit News published a very influential photojournalistic essay, "A Time of Tragedy," on August 11, 1967, less than two weeks after the smoke had cleared and the military troops had withdrawn from the city of Detroit. The investigative report, without any self-awareness, purports to speak for "Detroit" but really speaks from the perspective of the shock of white Detroit, and its white suburbs, and its white business and political leaders: "For most Detroiters, including those who lead the fifth largest city in the United States, there were no dark clouds . . . no quiet rumblings of a storm."

The first photograph in the report also highlights the "blind pig" above the printing shop at the intersection of 12th and Clairmount as "where it began." This starting point formulation, just like the viewpoint that there were "no quiet rumblings of a storm," is an erasure of history, an expression of white innocence, and a strategy to blame Detroit's African American residents for everything that ensued. The Kerner Commission rejected this verdict in its 1968 report labeling "white racism" the fundamental cause of civil unrest in Detroit and other cities, and the Michigan Historical Commission acknowledged this interpretation of history a half-century later. But plenty of civil rights and black power activists in Detroit--as this exhibit has documented--had been making this case for decades and warning that systematic police brutality combined with concentrated poverty, racial segregation, and other inequalities had created conditions that would foreseeably explode.

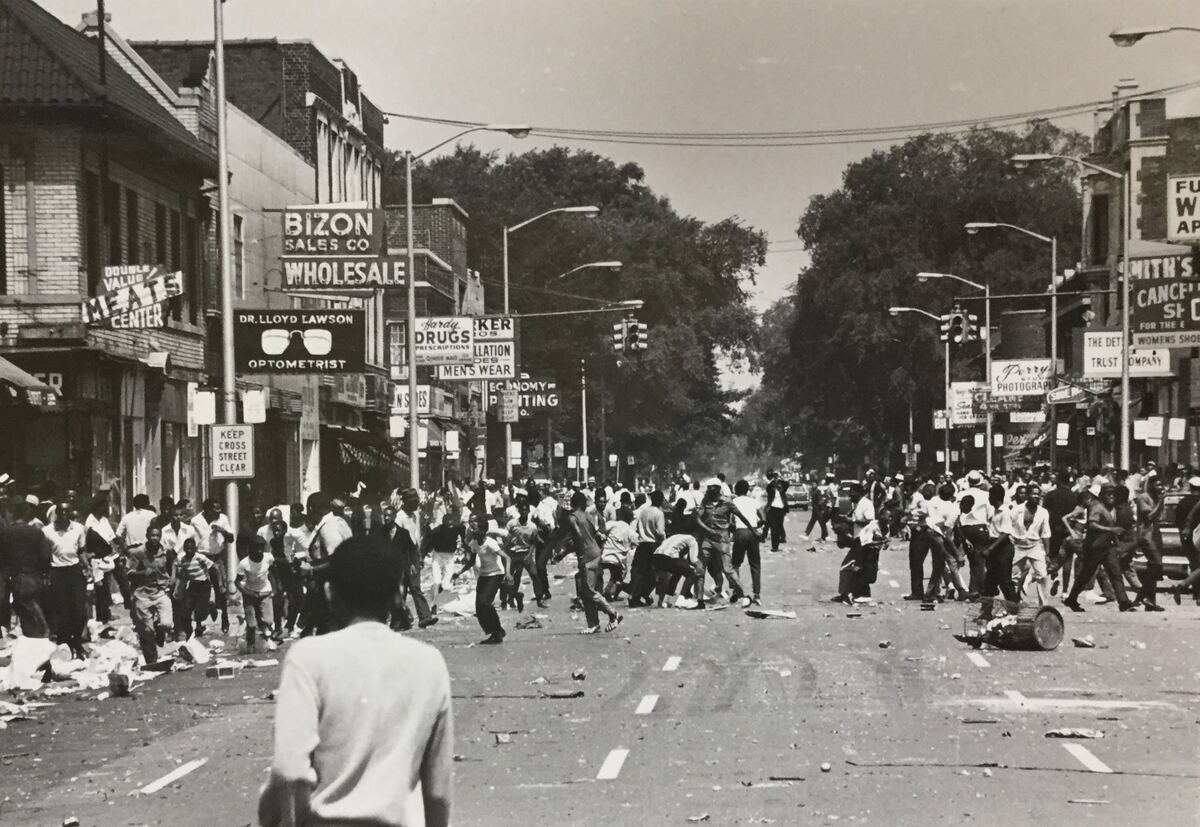

Criminalizing Black Detroit

The famous Detroit News photograph from the initial street scene at 12th and Clairmount, where the police raid of the blind pig triggered protests, is prominently displayed in the Detroit 1967 photographic collection at the Michigan State Archives with the caption "The riot started. The world saw this News photograph." This image of unruly African American youth, including some apparent preteens, operated (and still operates) to criminalize Black Detroit and to frame the events as a 'spontaneous' outburst. The police, whose crackdown and mass arrests at a peaceful gathering set these immediate events in motion, are missing from this photograph, although members of the news media are visible. The deeper causes that brought these historical actors to this particular place at this point in time are, of course, completely invisible.

The following four photographs, also from the "Riots and Protests. Detroit 1967" collection in the Michigan State Archives, are the only ones that also focus on African American people or their political slogans in the center of the frame. Compare these also to the main categories of military-oriented perspectives and scenes of property devastation on the next two pages of this section.

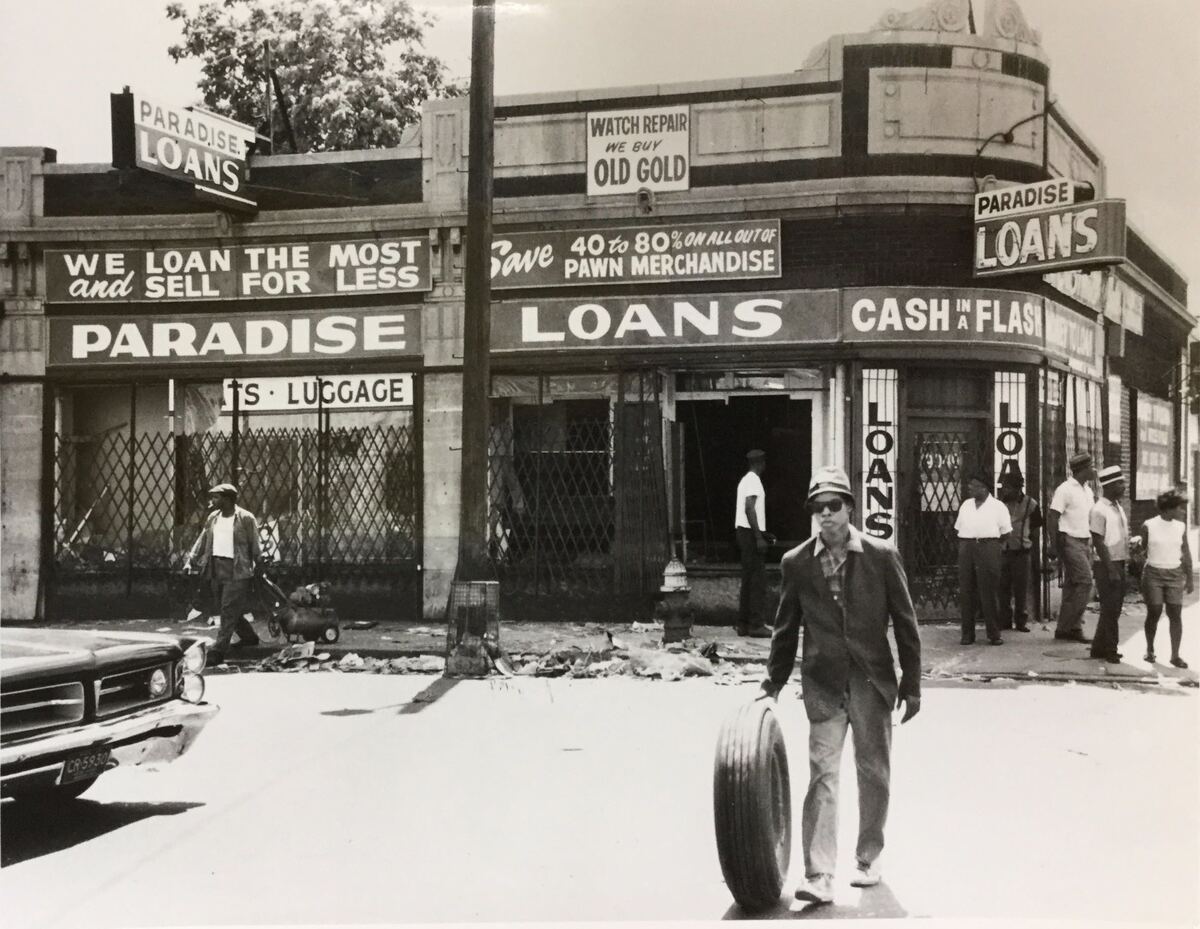

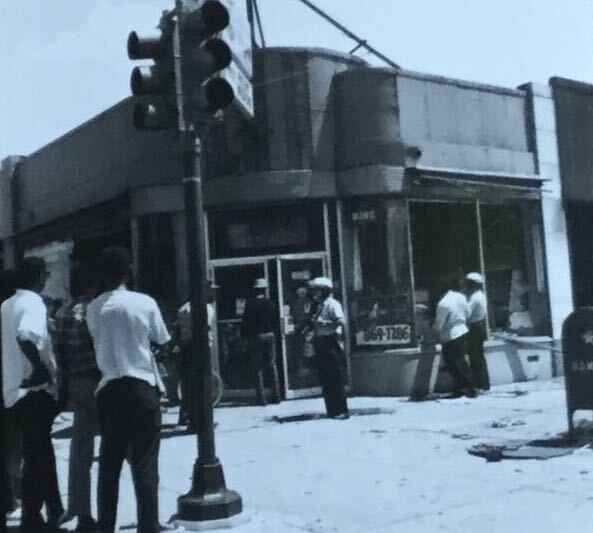

The next photograph is titled "Looting during the Detroit Riot of 1967." It is not self-evident from the image that any of the African American people captured in this photograph have committed the misdemeanor crime of stealing property, an offense for which Detroit Police Department officers shot and killed at least fifteen people during late July 1967, wounded far more, and arrested thousands. While "looting" certainly did occur, most of the African American adults in this image are standing in the daylight outside a payday loan store that probably was ransacked under cover of darkness hours or days earlier. They could be business owners themselves--although it is unlikely that any owned Paradise Loans, since this type of notoriously exploitative establishment was almost always owned by white outsiders from the suburbs. Who knows why the other man is calmly walking across the street with a tire, but it certainly did not come from the payday loan store, and there is no evidence that he is a "looter" either. The "looting" framework is collectively criminalizing these and all other African American residents of these Detroit neighborhoods and by extension justifying the state violence and military occupation of the "Detroit Riot."

The next photograph is captioned "Street Scene, Detroit Riot 1967." This photograph is ambiguous: a group of African Americans in the foreground observe two Detroit Police Department officers, one of whom seems to be standing guard outside of a store with broken windows. Three other African Americans, one on a bicycle, join the other police officer in looking through the windows. Everyone in the photograph--the African American residents and the white police officers--seems to be inspecting damage that happened hours or perhaps days earlier. Are they on the same side? Are they all lamenting the damage to their neighborhood? Why is the police officer holding a rifle and ready to shoot, during a peaceful scene in the middle of the day? What dangers does an armed law enforcement office pose in this situation? Is a misunderstanding just around the corner?

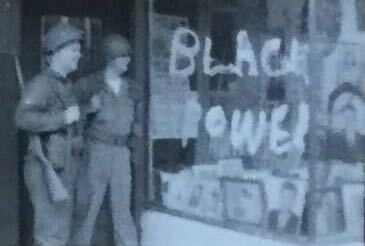

The next photograph (right) is captioned "Black Power Detroit Riot 1967." This image is of low quality but clearly shows two white National Guardsmen posing and laughing next to a store with "Black Power" painted on the window. The first thing to consider is why are they laughing, and why this image appears to be the product of an amateur rather than a professional photographer--are they posing for a souvenir to show their friends and family back home, to brag about the time that they occupied Black Detroit?

Also, according to legend, African American store owners--and perhaps even some savvy white owners--wrote slogans such as "Black Power" as a signal to the "looters" and "rioters" that their store should be spared. If this strategy worked, as it appears to have in the case of this intact store, that suggests that the label of an indiscriminate "Detroit Riot" is less accurate than the labels of "Detroit Rebellion" or "Detroit Uprising" (which the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab collectively decided to use in this exhibit).

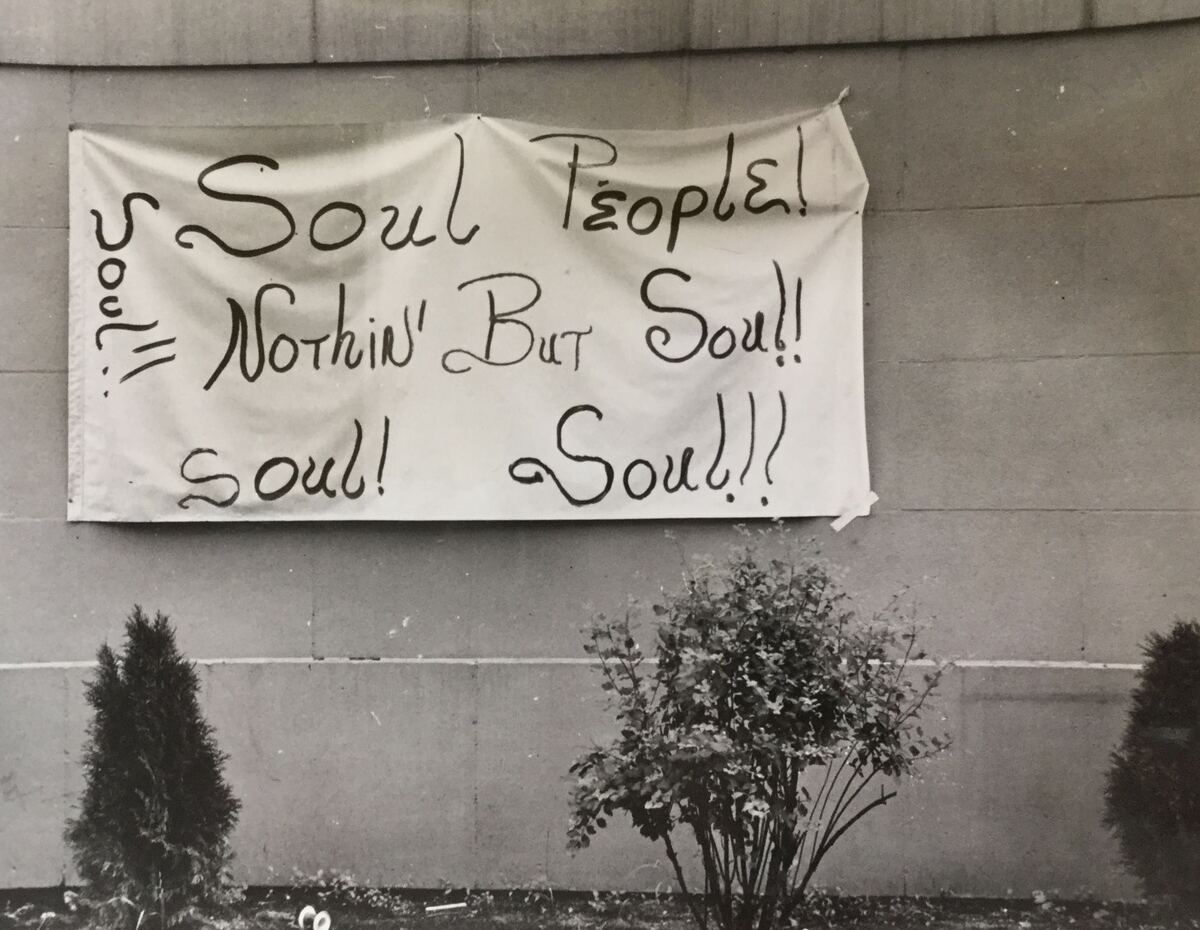

The final photograph in this sequence (below) represents Detroit as the home of the Motown Sound, a culturally vibrant community of African American entrepreneurs and performers and artists. This is a very different story about Black Detroit than the representation of the city as a riot-torn war zone, a place of crime and civil disorder. Motown artists with hit records in 1967 included Gladys Knight & the Pips, the Four Tops, the Miracles, the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, and Marvin Gaye. The creator of this sign was no doubt trying to send a message--to the surrounding black community, and probably also to the nation and the world--that the home of Motown was a city with soul.

Postscript: 12th and Clairmount Today

There are few traces of the 1967 Detroit Riot/Uprising/Rebellion left today at the corner of 12th and Clairmount, "where it began" according to the Detroit News. 12th Street is now Rosa Parks Blvd. The row of businesses that contained the blind pig, above the Economy Printing Company, is gone--demolished in yet another of Detroit's "urban renewal" projects. The state of Michigan's official historical marker, installed in 2017 in Gordon Park, is one of only two visible reminders of the history of this space. The other is this mural (below) on the side of a house across the street.

This mural, no less than the "black capitalist" enterprise of Motown, is evidence of the longstanding and continuing cultural and political vibrancy of Black Detroit, of the grassroots activism that transforms spaces of state power and violence into places of resistance and hope. The mural references black and white versions of Rosie the Riveter, the factory workers that symbolized Detroit during the boom years of World War II. The mural includes the manifestations of capitalist power in the half-century-long project to "rebuild" Detroit, from the Renaissance Center (now General Motors Headquarters) constructed in the 1970s to the controversial Q Line, a symbol of gentrification that runs along Woodward Avenue today and is the centerpiece of the metropolitan region's utterly inadequate mass transit system.

And at its center, the mural tells a story about the role of police brutality in the Detroit Uprising that is barely mentioned in the state's official historical marker: Detroit police officers and National Guardsmen with guns drawn while African American men are up against the wall, in a collage that includes the signs of the now-demolished Economy Printing Company on 12th and Clairmount, and of the Algiers Motel where Detroit Police Department officers murdered three African American teenagers in cold blood.

Note: Matt Lassiter created this page and the rest of the "Visualizing Detroit '67" section after the research team had completed its share of the project.

Sources for this page:

"Riots and Protests. Detroit 1967," General Photographic Collection, Michigan State Archives, Lansing, Michigan