STRESS on Trial

Left-wing radicals in Detroit endorsed the United Black Coalition's agenda to abolish STRESS and establish Black control of the city government and police department, but at the same time they believed that a political campaign led by the civil rights establishment and African American politicians would not be capable of mobilizing a mass movement for far-reaching transformation. Black and white radical organizations were deeply rooted in the city's rich history of left-wing unionism and black nationalism, shaped by socialist and Marxist ideologies and their recent New Left and Black Power variants. They viewed the problem of police brutality as a symptom of broader structures of capitalist oppression and corporate urban control of Black and poor people and the working class more generally. Unlike the NAACP and other mainstream civil rights groups, radicals envisioned a multiracial mass movement that would capitalize on the STRESS crisis to achieve working-class political power through a combination of street protests, courtroom struggles, militant unionism, and electoral mobilization.

Political Trials. Kenneth Cockrel and the Labor Defense Coalition (LDC) articulated this vision of a multiracial mass uprising through the formation of the State of Emergency Committee in the fall of 1971 and the grassroots "Abolish STRESS" campaign launched after the Rochester Street Massacre in spring 1972. Cockrel and Justin Ravitz, the radical Marxist attorneys who founded the LDC, believed that legal battles in the courtroom were also political trials that would mobilize and reinforce direct-action protests in the streets. In April 1972, alongside its "Abolish STRESS" petition drive, the Labor Defense Coalition filed a conspiracy lawsuit against the DPD, city government, and county prosecutor designed to place STRESS on trial in order to mobilize a mass movement against the "ruling class racists" who controlled state power. In a manifesto, "Why STRESS Must Be Abolished" (gallery below, left), Cockrel analyzed police violence as a corporate capitalist response to the political demands for self-determination by Black and poor people in the factories, schools, social welfare system, jails and prisons, and beyond.

A year later, after the outrages of the DPD manhunt, Cockrel and the LDC updated this vision through the formation of the Hayward Brown Defense Committee, arguing that the felony trials of the anti-narcotics activist could be transformed into a political trial of STRESS by combining the defense in the courtroom with mobilization of the "masses of the community" (right). Cockrel also criticized the United Black Coalition, which he had strategically joined, as an elite-led movement of "orthodox black community leaders and institutions [who] were able to escape responsibility for making an ongoing structural response to the underlying problem of our community, namely the absense of an organization involving the masses." The Labor Defense Committee would therefore turn the trial from defense to offense through "political organization on a mass basis," especially by connecting the violence of STRESS to the DPD complicity in narcotics trafficking in poor Black neighborhoods. This strategy was successful in convincing majority-Black juries to acquit Hayward Brown in three separate trials during spring 1973, as Cockrel turned the proceedings into a verdict on the criminality and racist abuses of STRESS and the Detroit Police Department.

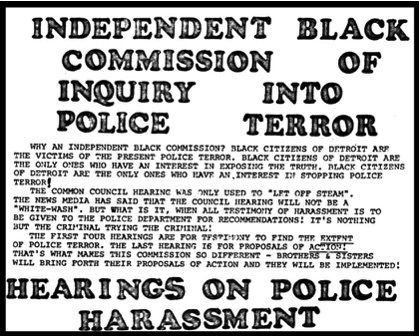

The remainder of this page explores two major efforts by radical activists to put the entire STRESS operation and the broader white-controlled power structure of the city of Detroit on trial in the courts and in the streets: the criminal conspiracy lawsuit filed by the Labor Defense Coalition in April 1972, and the community hearings organized by the Independent Black Commission on Inquiry into Police Terror in February 1973. The police terror hearings were organized by Black radicals from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), working alongside young black power activists who were students at Wayne State University. They deliberately placed STRESS and the DPD on trial in a public forum rather than a courtroom, both to mobilize the masses into a political movement and in recognition that the criminal justice system by design insulated the police department from accountability. The Socialist Workers Party called for a mass mobilization against STRESS, which it labeled a "terror squad whose sole purpose is to demoralize and demobilize the Black community." The SWP also argued that the election of Black politicians from the Democratic party would not be sufficient to transform the political oppression that STRESS embodied, and that the only solution was total community control at the local level: "Black people should have complete control over the police in their communities" (gallery below, right).

The STRESS Conspiracy Trial (May 1972)

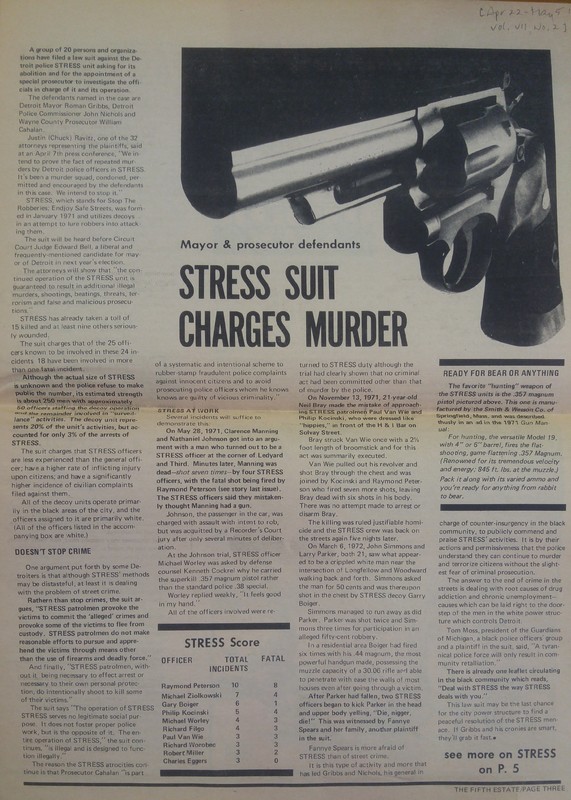

The Labor Defense Coalition filed the conspiracy lawsuit against STRESS on April 6, 1972, as part of the broader "Abolish STRESS" campaign that accelerated following the Rochester Street Massacre a month earlier. The lawsuit named Mayor Roman Gribbs, Police Commissioner John Nichols, and Prosecutor William Cahalan as defendants and accused them of an organized conspiracy to deploy the STRESS unit to commit illegal acts of violence in the streets and to cover up the murders and criminal assaults by the decoy operation. The plaintiffs included family members of several young men killed by STRESS units, a number of African Americans shot and wounded in non-fatal incidents, and a range of civil rights groups including the NAACP, ACLU, and Guardians of Michigan. The litigation asked for an injunction against undercover STRESS patrols and a court-appointed impartial investigator to replace the corrupt internal investigations by the accused co-conspirators of the STRESS "murder squad": the Detroit Police Department under Commissioner Nichols and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Officer under William Cahalan.

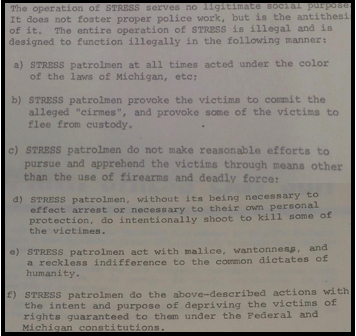

The Labor Defense Coalition's complaint charged that:

- "The operation of STRESS serves no legitimate social purpose. . . . The entire operation of STRESS is illegal and is designed to function illegally"

- "STRESS patrolmen provoke the victims to commit the alleged 'crimes,' and provoke some of the victims to flee from custody"

- "STRESS patrolmen do not make reasonable efforts to pursue and apprehend the victims through means other than the use of firearms and deadly force"

- "STRESS patrolmen, without it being necessary to effect arrest or necessary to their own personal protection, do intentionally shoot to kill some of the victims"

- Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan "is part of a systematic and intentional scheme to rubber-stamp fraudulent police complaints against innocent citizens and to avoid prosecuting police officers whom he knows are guilty of vicious criminality"

- "The continued operation of the STRESS unit is guaranteed to result in additional illegal murders, shootings, beatings, threats, terrorism, and false and malicious prosecutions"

The litigation focused specifically on nine of the first thirteen STRESS homicides during 1971: Herbert Childress, Clarence Manning, Horace Fennicks, Howard Moore, James Smith, Louis Ellios, James Henderson, Donald Saunders, and Neil Bray (see plaintiff's complaint in gallery below, left). The circumstances of these fatal shootings are analyzed in depth on the Remembering STRESS Victims page elsewhere in this section and will only briefly be summarized here. The LDC chose not to include the Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell fatalities in the lawsuit, even though the attorneys believed that the STRESS unit's actions were improper and probably criminal, because of the inconsistencies in the testimony of teenage witnesses who had faced police intimidation. The lawsuit also detailed the wrongful non-fatal shootings of four additional young Black men--Harold Singleton, John Simmons, Larry Parker, and Harry Taylor--assaulted by STRESS officers without cause and severely wounded by multiple gunshots while fleeing from their attackers. (Taylor later died of his injuries).

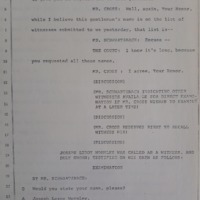

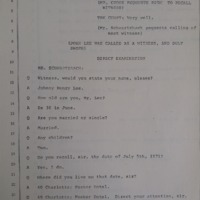

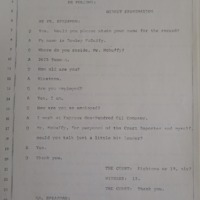

Testimony of STRESS Crimes. The LDC complaint and the eyewitness testimony at trial revealed a clear pattern of STRESS officers initiating confrontations that they then blamed on the victims, using deadly force as a first rather than last resort, shooting innocent people fleeing from police-instigated violence, planting knives or other alleged weapons on the deceased, and threatening or arresting witnesses on false charges to intimidate them into silence. According to the Labor Defense Coalition, DPD officers delivered death threats to at least one of the eyewitnesses who gave an affidavit and agree to testify that STRESS officers shot two men, Horace Fennicks and Howard Moore, without any provocation except their panhandling for a quarter. Three other witnesses did testify to the same effect, including Kenneth Hicks, who was shot and badly wounded in the same incident. The LDC solicited testimony from the medical examiner directly contradicting a STRESS patrolman's claims he had to shoot Donald Saunders because the deceased attacked with a knife after asking for 20 cents for bus fare. The autopsy report in the Clarence Manning killing contradicted Patrolman Raymond Peterson's cover story that the unarmed man had attacked him. Hotel clerk Rawley McDuffy testified that Patrolman Raymond Peterson and another STRESS officer shot James Henderson without provocation and then beat, arrested, and threatened to frame McDuffy in an effort to cover their tracks. Harry Taylor, severely disabled by STRESS gunfire, testified that a plainclothes officer walked up and shot him in the stomach as he left a bar for no reason at all. Taylor died six months later.

STRESS Trial Ordered to Halt. On May 12, after nine days of testimony exposing the methods and crimes of the STRESS decoy operations, the Michigan Court of Appeals granted the city's request to suspend the proceedings. The state appellate court had previously removed Prosecutor William Cahalan as a defendant, notwithstanding the success of the Labor Defense Coalition in securing eyewitness testimony about STRESS crimes that multiple prosecutorial inquiries and "justifiable homicide" findings had either neglected to uncover or just covered up. Circuit Court Judge Edward Bell, an African American who had presided over the STRESS trial thus far, publicly warned that the appellate court's shutdown would reinforce community sentiment that the scales of justice in Detroit were rigged.

In late May, the Michigan Supreme Court reinstated the STRESS lawsuit, but the proceedings ended up in the docket of a different and much less sympathetic judge after Edward Bell resigned in order to prepare a mayoral campaign. This was a fateful twist, as Circuit Judge John O'Hair promptly postponed the proceedings for two years and then denied the Labor Defense Coalition's request for a temporary injunction against deployment of the STRESS unit until the end of the trial. LDC attorneys Justin Ravitz and Ken Cockrel denounced Judge O'Hair for conspiring with the mayor, prosecutor, and DPD to kill the lawsuit. With the formal legal avenue closed down, the next trial of STRESS would take place through community hearings organized by radicals rather than in the courtroom, as recounted in the next section on this page.

The gallery below contains arguments and testimony from the uncompleted STRESS trial revealing extensive corruption, criminality, excessive use of force, and murder by DPD officers. Visit the Remembering STRESS Victims page for more detailed accounts of all of these incidents.

Labor Defense Coalition's "Complaint" in STRESS lawsuit, detailing wrongful shootings of 12 people (17 pg. excerpt)

Ken Hicks testimony of unprovoked STRESS shooting in Fennicks and Moore killings; Hicks was also shot

Independent Black Commission of Inquiry into Police Terror (February 1973)

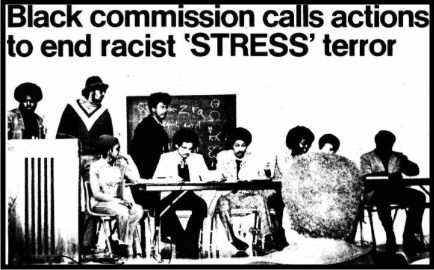

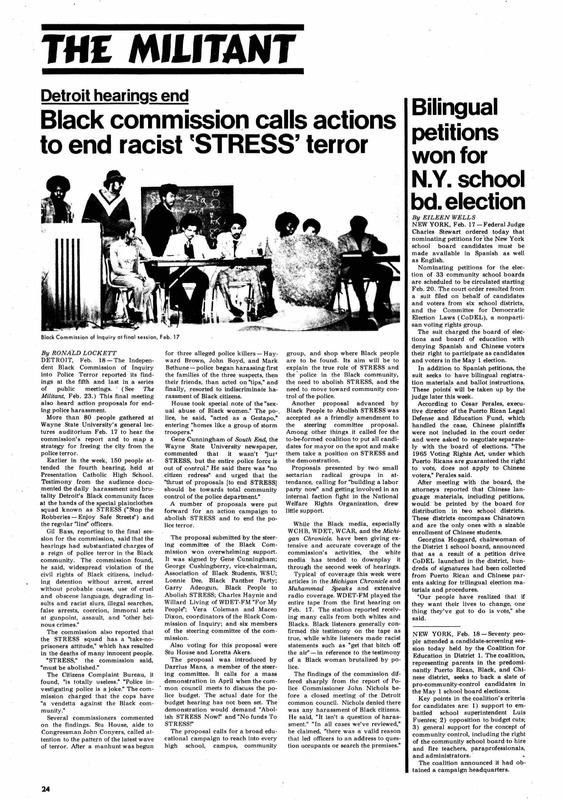

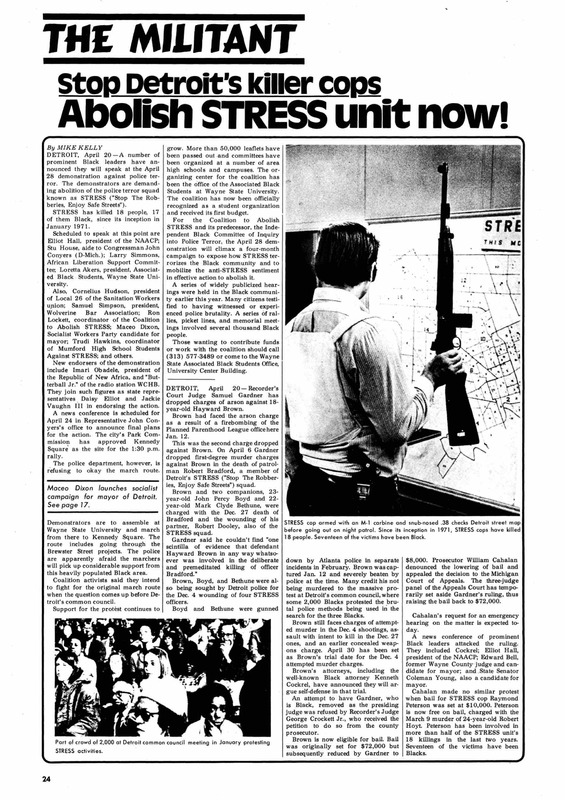

In response to the DPD's brutal manhunt, radical activists from the Socialist Workers Party and their allies organized five community hearings between February 5-17, 1973, to investigate police terror and convict STRESS through a public trial via people's tribunal. Maceo Dixon and Ron Lockett, two young African American leaders in the SWP, were the driving force behind the hearings organized by the Independent Black Commission of Inquiry into Police Terror. Dixon was a 24-year-old activist who campaigned for mayor on the SWP ticket in 1973, and Lockett was a 21-year-old senior at Wayne State University. The men had endorsed the United Black Coalition but also considered the political analysis of mainstream civil rights groups to be far too timid and oriented toward liberal reformism within the system. The NAACP-led United Black Coalition did issue a call for an independent investigation into the DPD's manhunt abuses but envisioned such an inquiry taking place under the auspices of a legal authority such as the state civil rights commission or the FBI. The Socialist Workers Party, along with other local black power organizations in Detroit, instead believed that the investigation of STRESS and the DPD should be conducted by Black citizens as part of a broader move toward working-class Black community control of the police department and city government.

Maceo Dixon and Ron Lockett outlined their vision for the Independent Black Commission of Inquiry into Police Terror in a position paper released in advance of the proceedings (right). They portrayed STRESS as a criminal state enterprise "willing to do anything to maintain their death grip on the Black community." They argued that the manhunt abuses made clear that no Black people were safe, including the middle class and elite who might previously have viewed STRESS and the DPD as protecting them from street crime by the "criminal element." But in truth, the fundamental threat came from the "criminal activities that the Detroit Police Department inflicts upon Detroit's Black community." Dixon and Lockett argued that the DPD and the white media had fabricated the myth that STRESS had reduced crime rates, based on lies that had unfortunately convinced many regular Black citizens that they needed an aggressive police presence for their protection. The hearings conducted by the Independent Black Commission would expose the truth, that the DPD--"Detroit's racist law enforcement agency"--had increased the crime problem through the expansion of state criminality and represented the greatest threat to the lives, property, and very survival of Black people in the city.

Police Terror Hearings. The five hearings conducted by the Independent Black Commission of Inquiry into Police Terror took place in two churches, a high school, at Wayne State University, and at the North End Family Center where STRESS officers killed Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell in September 1971. Black students at Wayne State played a major role in organizing the events, and the commission selected Louella Buck, the mother of STRESS victim Ricardo Buck, as the honorary chairwoman. Ron Lockett, one of the SWP organizers, chronicled each of the proceedings for The Militant, a national Socialist weekly publication (gallery below). The local network television stations also provided substantial coverage. A fairly broad and rotating cross-section of Black community leaders and activists sat as the commission 'jury' for each of the hearings, and many ordinary working-class and middle-class citizens took the opportunity to tell their stories of police violence and oppression. At the first hearing, witnesses testified about the brutality of the recent STRESS manhunt but also gave extensive accounts of everyday police harassment and misconduct, of white officers pulling them or their sons over for no reason and beating, racially abusing, and wrongfully arresting innocent people again and again. "Blacks from all walks of life" testified at the subsequent hearings, including a real estate broker who said that the DPD was "as racist" as police in Mississippi and many other citizens who condemned the daily injustices and brutality of racist "stop-and-search" policing.

At the final hearing, the commissioners reported that the independent investigation had confirmed:

- "a reign of police terror in the Black community"

- murders of "many innocent people"

- "widespread violation of the civil rights of Black citizens," including illegal detentions without arrest, wrongful arrests, and unconstitutional searches and seizures

- frequent use of racist and degrading language by police officers

- "immoral" acts at gunpoint, particularly "sexual abuse of Black women"

- assault, brutality, and other "heinous crimes"

- the "totally useless" nature of the Citizens Complaint Bureau, the DPD's internal investigative arm

Coalition to Abolish STRESS formed. The Independent Black Commission concluded that "STRESS must be abolished" but also emphasized that "the entire police department is out of control." The only solution, in the words of Gene Cunningham, a Black student leader at Wayne State, was "total community control of the police department." The commission also called for a campaign of political education and mass mobilization of the Black community in high schools and college campuses and through community organanizations, including but not limited to demanding that mayoral candidates commit to the abolition of STRESS. To this end, the organizers and participants in the hearings formed a new Coalition to Abolish STRESS to mobilize a mass movement in the streets, culminating in a large rally and demonstration on April 20 (covered on the next page).

Radical organizations did not ultimately succeed in taking neighborhood-level community control of the city government or the police department through their combined strategy of political trials and mass mobilization. But they did play a crucial role in the anti-STRESS campaign by exposing the scale of the DPD's racist brutality and by mobilizing regular people and especially Black youth in a protest movement that pushed mainstream civil rights organizations and local African American politicians to more aggressively condemn the DPD. This helped to make STRESS and racist police terror the central issue in the 1973 mayoral election of a city starkly polarized along racial lines. Read coverage of the hearings conducted by the Independent Black Commission of Inquiry into Police Terror in the gallery below, and proceed to the next page for the culmination of this campaign to abolish STRESS.

Sources

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Toni Swanger Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Community Relations Bureau, RG 83-55, Michigan State Archives

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

"Suit Attacks Legality of STRESS," Changeover, April-May 1972

"STRESS Suit Charges Murder," Fifth Estate, April 22-May 5, 1972

Detroit Free Press, March 23, May 13, June 1, 7, 1972

Michigan Chronicle, May 13, June 10, 1972, Feb. 17, 1973

The Fifth Estate, 1972-1973

The Militant, Feb. 16, 23, March 2, April 4, 1973

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2001)