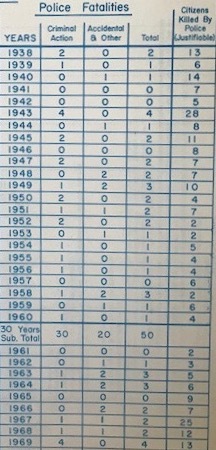

Police Homicides + Shootings 1964-66

Between 1964 and 1966, Detroit Police Department officers shot and/or killed the 33 civilians listed on the map below. The 17 fatal shootings specifically identified by our team through laborious archival and newspaper research represent three-fourths of the 23 officially acknowledged on-duty police killings during this time period, and even this official total is certainly an undercount. The map also includes 16 identified instances of nonfatal police shootings of civilians, an estimated one-fifth of the total.

African American males represented slightly more than half of the identified police homicide cases, although it is likely that most of the six unidentified fatal shootings also were of Black residents of Detroit, because of the ways in which race shaped media coverage of whose lives deserved attention. Interestingly, almost all identified non-fatal shootings involved African American males, often juveniles fleeing from police after alleged minor property crimes. This discrepancy is likely because white males killed by police were much more likely to be armed with guns and in the commission of serious crimes, and particularly more likely to fire on the police first, inviting an overwhelming response.

The DPD's "Use of Firearm in Police Action" policy (right), revised in 1962 and operative through mid-1967, gave officers the right to use fatal force to protect themselves or others from death or "serious bodily injury," and "when it is necessary to apprehend or prevent escape of a known felon, when the capture or recapture of the felon cannot be accomplished by any other means." The policy also required the police officer to have personally witnessed the felony in order to fire on a person who tried to escape, and not to shoot people fleeing to avoid arrest for a "minor offense." Many felony categories, however, were broadly defined in state law and gave the DPD and the prosecutor enormous discretion to reclassify the actions of unarmed people as serious crimes, including nonviolent burglary, reckless driving, and officer allegations that the suspect resisted arrest with some sort of weapon or other "dangerous" threat.

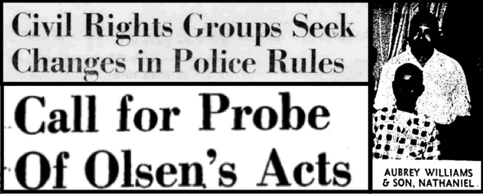

The Wayne County Prosecutor, Samuel Olsen, exonerated the police officers in every fatal and non-fatal shooting during this time period. In the spring of 1965, a coalition of civil rights groups files a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission charging that Prosecutor Olsen "has systematically discriminated against Negroes . . . in the enforcement of the criminal laws of Michigan." The complaint specifically referenced the exoneration of white DPD officers for shooting two unarmed and fleeing Black juveniles, Clifton Allen and Nathaniel Williams, during 1964 (both cases detailed below).

This interactive map documents 17 fatal police shootings of civilians and 16 non-fatal shootings in the city of Detroit between 1964 and 1966, based in the city's racial demographics at the time of the 1970 census. The darkest-blue areas represent the most segregated Black neighborhoods, and the darkest green areas indicate the all-white sections of the city, with the evolving color line in-between. Because this time period falls in the middle of the decade, some of the lighter-blue census tracts along Detroit's racial boundary appear to have more African American residents than they probably did at the time of the incident. But as an overall depiction of Detroit's racial landscape, the map is accurate enough to illuminate the clear distinction between white people killed by police in the intensely segregated outlying parts of the city and African American people killed by police in the identifiably Black parts of the city or along their racial boundaries and more integrated commercial corridors.

Click on the dots to read the incident description and see the source for each police shooting. Key findings, pattern analysis, and in-depth features on each police homicide are below the map.

Map of Police-Involved Homicides and Shootings of Civilians, 1964-1966, in Detroit's Racial Geography

- Black dots (17) = Police Homicides of Civilian

- Red dots (16) = Police Shootings of Civilian (nonfatal)

Key Findings:

- "Justifiable Homicide" (100%). The DPD's internal Trial Board and the Wayne County Prosecutor found all of the fatal and non-fatal police shootings documented in this map to be legally justified, regardless of the circumstances, indicating a de facto policy to exonerate officers for all fatal force incidents "in the line of duty" evident in every time period covered in this exhibit. Civil rights groups protested exonerations in the Clifton Allen, Nathaniel Williams, and James Sabra killings, discussed below.

- Race (53% confirmed Black; est. 67% Black). Of the 17 homicides identified, 9 involved African Americans and 8 involved white males. As explained above, it is likely that all of the 6 unidentified homicides involved Black males, leading to an estimate that around two-thirds of the fatalities were African American, which is roughly in line with the trends from the previous and subsequent time periods.

- Gender (100% Male). All police homicide cases were of males, as were all identified non-fatal shootings, except for a suspicious case when a white officer shot a Black female sex worker in 1965. The officer claimed it was an accident, but the NAACP demanded an investigation.

- Unarmed and Fleeing (35%). In 6 of the identified homicide incidents, the civilian was unarmed and fleeing from the police on foot when shot from behind. Half of these identified victims were African American, and half were white. Two incidents where the suspect had a weapon but was not threatening officers during an escape attempt are included here. All involved nonviolent burglary or petty theft.

- "Armed and Dangerous" (29% definite; 52% including alleged). In 5 of the homicides, the person killed was involved in serious criminal activity, usually armed robbery, and fired a gun at the officers. Four of the five perpetrators were white. These were the only cases of clear self-defense by officers to protect life. In two other cases, the suspects had guns but were fleeing from the officers when killed, and two others involved police intervention during holdups with a gun or knife involved.

- Domestic Disturbances and Mental Health Crises (24%). In four of the cases, the police used fatal force against men undergoing a mental health emergency, threatening members of their family, or both. One of those killed was definitely armed and dangerous, one family quarrel situation (James Sabra) appeared to involve unprosecuted murder by the officer, and two were tragedies where the police responded with extremely disproportionate force.

- Adults (88%) and Juveniles (12%). The vast majority (15) of homicides involved adults, and 2 involved juveniles, both African Americans shot while unarmed and fleeing from alleged petty theft scenarios. This reduction in police killings of juveniles likely reflects changes in department procedures and training norms in response to the mass protests that followed the killing of unarmed and fleeing teenagers during 1962-1963, given that one-fourth of all police homicides between 1957-1963 were of juveniles. Civil rights groups also intensely protested the 1964 homicide of unarmed 15-year-old Nathaniel Williams, recounted below. However, our project has identified 7 non-fatal shoootings of unarmed and fleeing teenagers between 1964-1966, including 5 Black youth, and there were likely quite a few others that did not make the newspapers.

17 Homicides by Detroit Police Officers, 1964-1966

All 17 identified homicides by DPD officers are featured below, divided into four categories:

- controversial killings of unarmed Black males that prompted civil rights protests (including two teenagers depicted in the red circles on the map below right)

- killings of other unarmed and fleeing males that barely left a trace in the archives

- killings of people during "family trouble" or mental health situations

- killings of armed or allegedly armed men engaged in criminal activity

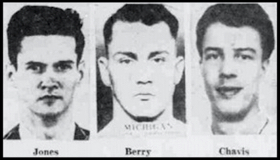

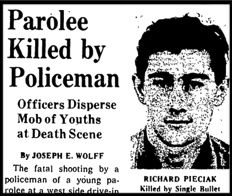

Note on Photographs and Media Coverage: The mainstream newspapers, the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News, published photographs of all of the while males killed by police between 1964-1966 and none of the Black males. The visual representation of white males was not only about the racial politics of media coverage but also because all of them had criminal records and mug shots on file with the police, whereas none of the Black males killed by police had adult criminal records except Andre D'Artagan. The mainstream newspapers also provided far more coverage of white police-involved fatalities; the police homicides of Black males almost never made the front page and often received no attention at all. Most reports on African Americans killed by the police come from the Michigan Chronicle, the city's Black weekly, and the files of civil rights organizations and agencies.

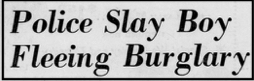

Note on Police Shootings of Teenagers: DPD officers shot and killed 2 teenagers between 1964 and 1966, both African American males who were unarmed and fleeing from alleged petty theft scenarios, as detailed in Category 1 next. It is noteworthy that both homicides occurred along racial borders on the West Side of the segregated city of Detroit, as the red circles on the map at right reveal, meaning that the killings occurred to protect white-owned property from petty theft by Black youth. Police officers or private police guards additionally shot 7 teenagers non-fatally during this period, that our project has identified through news reports (the actual total is likely several times higher). Most of these also involved unarmed youth allegedly engaged in property crimes (purple circles on map).

The number and percentage of teenagers killed by the DPD between 1964 and 1966 was much lower than the 21 teenagers killed between 1968 and 1973 (see here and here), when the police department deliberately liberalized its use of force policies to grant officers almost unlimited discretion to shoot unarmed and fleeing people, including youth, and when the DPD prioritized deterrent force against Black youth in particular to protect white property from burglary in the downtown region and along racial boundaries. The two homicides of young Black teenagers who were unarmed, alleged "burglars" during 1964 were therefore the harbinger of a much greater wave of police violence, but it is also possible that the major protests that greeted each of these events scaled back police use of force against unarmed teenagers until the Detroit 1967 Uprising unleashed it with a vengeance.

Category 1: Police Homicides of Unarmed Black Males Protested by Civil Rights Groups

Clifton Jerome Allen (July 2, 1964). Allen, a 17-year-old African American male, was unarmed and shot fatally in the back of the head by Sergeant Louis Causi at 10:47 p.m. while Allen was running away from the site of a suspected burglary at a medical supply firm. The caller reported to police that $1.83 had been stolen from a petty cash box, although police found no money on Clifton Allen or his companion, the alleged lookout. Sgt. Causi, a white officer, reported that he fired a warning shot into the ground after he identified himself and shouted for Allen to halt while chasing him through an alley. Causi fired the final shot from his revolver at Allen from 100 feet away after the youth continued to flee. Clifton Allen died an hour later at Detroit General Hospital. A coalition of civil rights groups protested Prosecutor Samuel Olsen's decision to exonerate Sgt. Causi despite the facts that Clifton Allen had not committed a felony and the shooting appeared to violate DPD use of force policies.

Nathaniel Williams (Dec. 24, 1964). Williams, a 15-year-old African American male, was shot in the head and killed by Patrolman Calvin Berry around 9:00 a.m. Williams was unarmed and fleeing, with a 14-year-old companion, from an alleged burglary attempt of a home. Patrolman Berry and his partner, both white officers, responded to a report of a burglary in progress, and he shot at the boys through a window when he saw them running away, hitting Nathaniel Williams above the left eye. Prosecutor Samuel Olsen exonerated the officer for discharging his weapon "in the line of duty" and stated that the youth was in the process of committing a felony [burglary] and that his age "had no legal bearing" on the determination.

The senseless killing of Nathaniel Williams generated protests from his family and a coalition of ten civil rights groups, including the NAACP, Urban League, and Adult Community Movement for Equality. They demanded strict new regulations to ban police use of deadly force in situations involving unarmed and fleeing suspects, particularly teenagers, who posed no threat to anyone and whose alleged crimes were minor. Reverend James Wadsworth of the NAACP told the Detroit Free Press: "Here was a boy who was guilty of breaking and entering being executed by the police. We don't condone crime or minimize the seriousness of breaking and entering. But a policeman should shoot to kill only if he or someone else is in grave danger." The coalition also filed a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission charging Prosecutor Olsen with systematic racial discrimination against "the Negro population of Wayne County," citing in particular the exoneration of the white officers in the fatal shootings of juveniles Clifton Allen and Nathaniel Williams. Nathaniel's bereaved parents protested directly to the police department, announced plans to file a lawsuit, placed their son's picture in a Michigan Chronicle story about his life and not just his death (right), and demanded "that justice is done," in his father Aubrey's words.

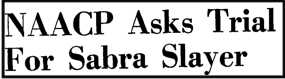

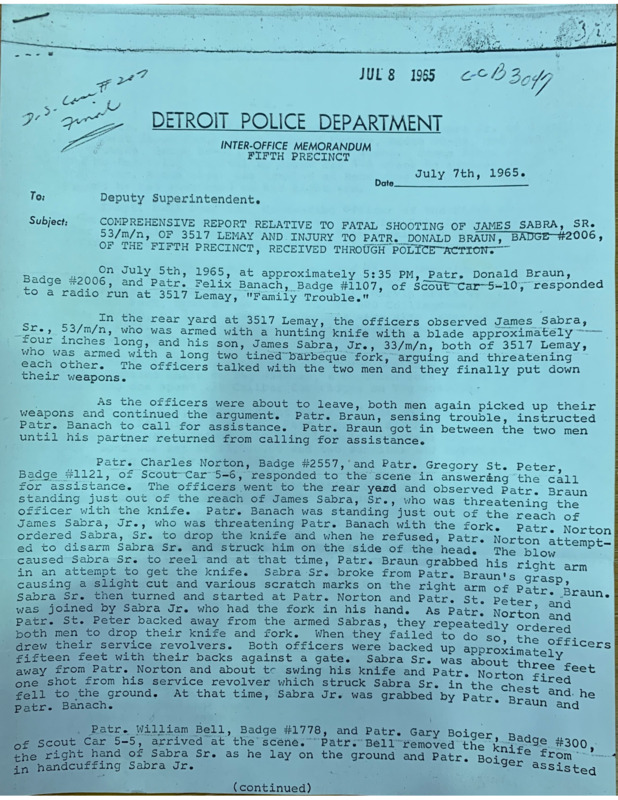

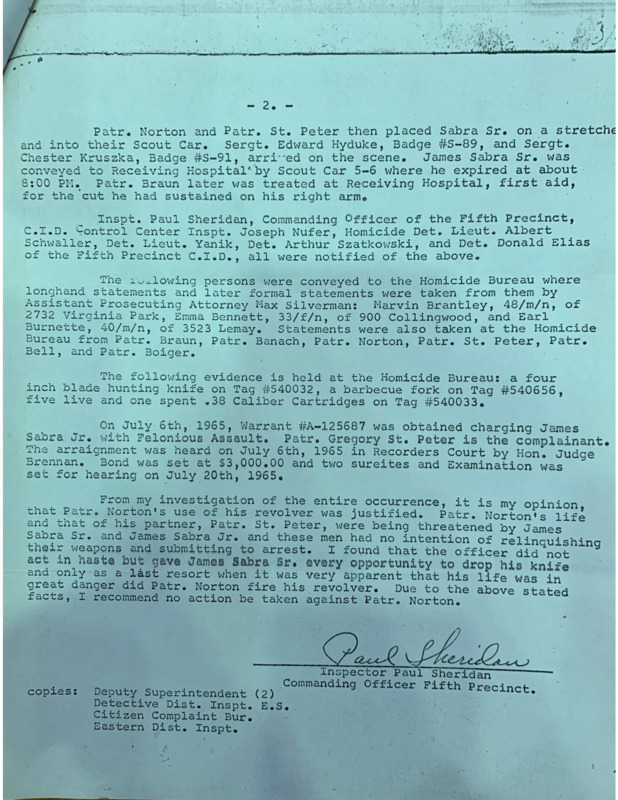

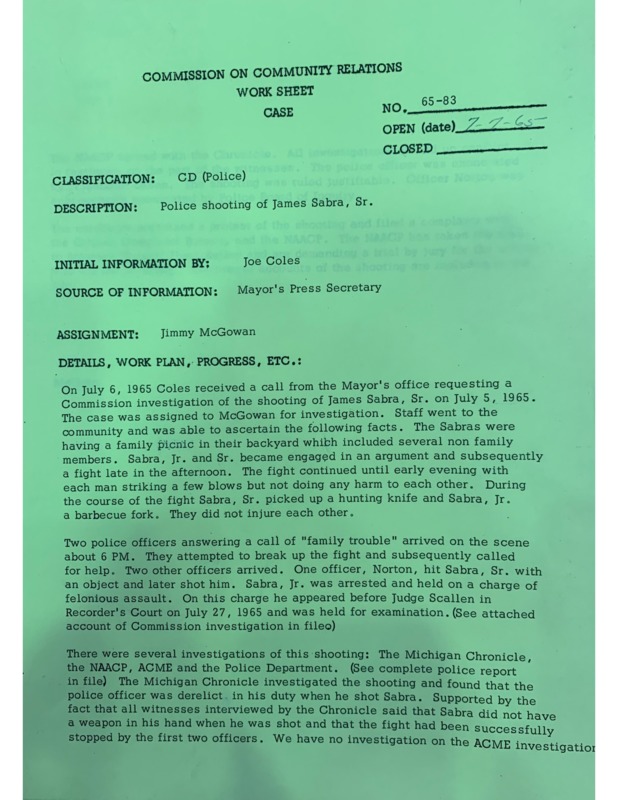

James Sabra, Sr. (July 4, 1965). Sabra, a 53-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Charles Norton, a white officer, without provocation and in circumstances covered up by the policemen present and by the DPD's internal investigation. The Sabra family was holding a holiday picnic in their backyard when an argument developed between Sabra and his son, James Sabra, Jr. Two officers responded to a "family trouble" call made by a neighbor and encountered the father holding a hunting knife and the son holding a barbecue fork. Both Sabras complied with the officers' order to put down their weapons and were standing there talking to the policemen when the situation escalated.

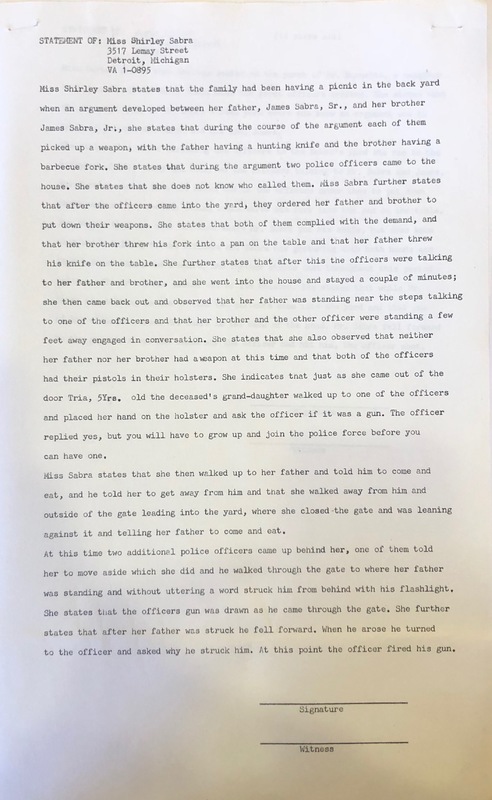

The responding officers had called for backup, and Patrolman Norton arrived with his partner. According to six eyewitnesses (gallery below, right), Patrolman Norton walked into the yard and smashed James Sabra, Sr., in the back of the head with a flashlight without saying a word. Mr. Sabra, who was no longer armed, then turned around and asked why the officer had struck him, and Patrolman North raised his revolver and shot Sabra in the chest. The four police officers then handcuffed the wounded Sabra, Sr., and took him to the hospital, where he died two hours later. They arrested his son, James Sabra, Jr., for felonious assault.

The DPD officers present then fabricated a cover story that both Sabras, father and son, were threatening the first two patrolmen with the hunting knife and barbeque fork when Patrolman Norton intervened to protect their lives. Norton claimed that he ordered Sabra, Sr., to drop the knife, but instead he slashed one of the other officers and then both father and son advanced on Norton and his partner with their weapons in hand. Norton claimed that Sabra, Sr., swung the knife at him from three feet way, and so he responded by firing to protect himself and the other officers (gallery below, left). Prosecutor Samuel Olsen accepted the police version at face value and declared the death of James Sabra, Sr., to be a "justifiable" homicide.

The NAACP and the Michigan Chronicle conducted investigations and uncovered a consistent story told by the African American civilian witnesses, including neighbors not involved in the picnic, that Patrolman Norton had murdered the unarmed James Sabra, Sr., by attacking him from behind and then shooting him. It is obvious when comparing the DPD's whitewashed investigative report to the witness statements that the shooting was unjustified. The NAACP accused the prosecutor of being unable or unwilling to distinguish "fact from fiction" and demanded without success that a jury trial should determine the guilt or innocence of Patrolman Charles Norton. Read documents about this case in the gallery below.

Category 2: Police Homicides of Additional Unarmed Males

Arthur G. Barrington (May 11, 1965). Barrinton, a 31-year-old white male, was shot and killed while unarmed and fleeing by Sergeant William Gerlach shortly before 2:00 a.m. Gerlach and his partner responded to a report of a break-in at the Michigan Employment Security Commission Building and saw a man running from the scene. They gave chase, and Sgt. Gerlach stated that he warned the suspect to stop and then fired one shot when he continued to flee, striking Barrington in the lower back. Barrington reportedly had a stolen wallet in his pocket and died several hours later at the hospital. The Detroit Free Press published Barrington's mug shot (left), and its headling emphasized his criminal record and past incarceration and not the fact that he was unarmed and posed no threat to anyone when killed.

Roger Curry (July 22, 1965). Curry, a 21-year-old African American male, was shot in the chest and killed by Patrolman Percy Hart, a Black officer, during a traffic stop after midnight. Patrolman Hart and his partner pulled over a car for speeding and asked Curry for his driver's license and registration. Curry gave the officer a license in the name of his brother, Leroy Curry, with the car registered in his own name. The officers told Curry he would have to clear up the matter at the police station, and at this point that state that Curry told the partner, Ptr. Donald Magdowski, to take his hands off the car. The officers then alleged that Curry resisted and, during a scuffle, reached his hand into his pocket and said, "I'll get you." Patrolman Hart then shot Roger Curry, allegedly after Curry had tried to grab the officer's gun and then advanced on the two armed officers.

Category 3: Domestic Disturbance and Mental Health Situations

Note: the James Sabra homicide (above) also began as a "family trouble" call.

James (Johnny) Williams (Feb. 14, 1964). Williams, a 41-year-old African American male, was shot and killed at his home during a domestic disturbance situation around 10:30 p.m. by Patrolmen Sidney Oram, Lawrence F. Sebastian, Donald Zielinski, and Terrance Wright. The officers were responding to a report that Williams had threatened to shoot his cousin Minnie Carter because he suspected that she was sheltering his wife, with whom he had had an argument. The officers claimed that Williams was holding a shotgun when they arrived, and Patrolman Sebastian opened fire and stated that he had seen Williams aim the gun at them. It turned out that the shotgun was empty. The patrolmen fired ten shots at Williams, who died with bullet wounds in the chest, side, and forearm.

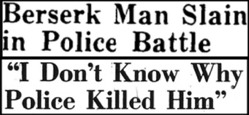

Julius Malone (Sept. 19, 1966). Malone, a 26-year-old African American male, was shot in the chest and killed by Patrolman Leland Kennedy in the kitchen of Malone's home. Malone was a patient of the Ypsilanti State Hospital, a psychiatric institution, and had left without permission to visit his wife Patricia Malone and their three children in Detroit. When Mrs. Malone realized this, she called the city physician's office, who told her that medical professionals could not come out without being accompanied by police officers. The next morning, Patrolman Kennedy and his partner, both white officers, arrived to transport Malone back to the Ypsilanti State Hospital. Julius was still in bed and he went to the kitchen, lit a cigarette, took out a boning knife, and told the officers he was not going back. According to Mrs. Malone, the officers told her that they would have to kill him if she did not get some assistance. She asked them to leave, and when that did not work she contacted a downstairs neighbor, who called the police department. Multiple officers responded and cornered Julius Malone in the corner of the kitchen. Patrolman Kennedy shot and killed him, and the officers alleged that Julius Malone had lunged at them with the knife.

The Detroit News reported the case as the police described it: a straightforward and justified police use of deadly force against a "berserk man." The Michigan Chronicle interviewed the young widow and shaped its coverage of the tragedy around her account, not the police department's, shifting blame from Julius Malone to the officers and more broadly to DPD policies and procedures, which responded to people undergoing mental health emergencies with armed force. Patricia Malone said:

Category 4: Police Homicides of Armed Criminals or Questionable Allegedly Armed Scenarios

Seven of the ten armed or allegedly armed people killed by police officers and covered in this section were white. The white males all had criminal records, and the mainstream newspapers reported the version provided by the police department, including emphasizing that the dead person was an "ex-convict" or "parolee" or "narcotics addict," which sidelined questions of whether the use of fatal force was necessary. At least three of the homicides below (Ellington, Pieciak, Redding" appear questionable and arguable involved excessive force, even if they could be legally justified under the permissive rules of engagement at the time.

Edward Ellington (Nov. 14, 1964). Ellington, a 39-year-old African American male, was fatally shot in the chest and forearm by Patrolman Robert A. Sekula in an East Side bar on November 14, 1964. Sekula and his partner Richard Evans were responding to a call from the owner that Ellington was refusing to leave. They claimed that Ellington was holding a hunting knife when they arrived and advanced on them. Patrolman Sekula said that he asked Ellington to drop the knife three times before firing two shots at Ellington, killing him.

Andre Rene D'Artagan (Dec. 12, 1964). D'Artagan, a 32-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Ray Shriner in a dangerous gunfight that escalated from a family crisis situation. The wife of Andre D'Artagan reported to police that he had threatened to kill her and that he was wanted for burglary and arson by the Los Angeles Police Department. Officers engaged in a high-speed 21-minute case that started on the Lodge Freeway in pursuit of a car carrying both Andre D'Artagan and his wife. Police fired multiple shots at the vehicle, even though the victim who had reported the incident was inside, and Andre D'Artagan also fired back. On the outskirts of the city, Andre D'Artagan stopped the car and ran into the backyard of a house. From there, he shot and killed Patrolman Howard Tulke, a white officer, pictured in the front-page story at right. Patrolman Shriner and several other officers opened fire and killed D'Artagan with seven bullet wounds.

The Detroit News front-page article about this wild event is a revealing insight into the racial politics of media coverage of crime and police violence. It was the only time identified by our research team when a police killing of an African American received above-the-fold coverage in a mainstream newspaper during this era. What made the story explosive, of course, was not only the high-speed car chase and gunfight but the fact that an African American had killed a white officer. The article did not include a picture of Andre D'Artagan--unlike all of the white men covered in this section--and portrayed him as a career criminal and "ex-convict" brought down by police "in a fullisade of gunfire." By contrast, the photographs of the white officers are prominent, along with extensive personal information about the patrolman killed by D'Artagan. A white bystander injured in the crossfire is also pictured. The only image related to D'Artagan is a picture of his gun. The Detroit Free Press front-page coverage was similar.

William Berry and Jimmy Chavis (May 17, 1965). Berry, a 24-year-old white male, and Chavis, a 23-year-old white male, were shot and killed by police officers during a car chase after midnight after the two men had fatally shot Dennis Wayne Jones, a 23-year-old white male, during a bar fight. Berry and Chavis put Jones's body in the backseat of their vehicle and fled with a police squad car in pursuit. The four police officers stated that William Berry began firing at them out of the car window, so they all opened fire with shotguns and revolvers. Berry had fatal gunshot wounds to the head and neck, and Chavis was hit three times in the chest. A third fugitive somehow emerged unscathed. The Detroit Free Press coverage (right) included photographs, presumably mug shots, of the two dead white and their victim, Dennis Jones. This was in contrast to African Americans killed by police, who almost never had their photographs in the newspapers unless it was the Michigan Chronicle, the Black weekly.

Melvin Blake (July 25, 1965). Blake, a 34-year-old white male, was shot in the back of the neck and killed by Patrolman Walter Pezda while running from police after allegedly robbing a supermarket in Northwest Detroit. Several store employees and customers were chasing Blake and notified Ptr. Pezda, who was driving by in a scout car. Blake allegedly tried to shoot Pezda, but his gun backfired. The brief newspaper coverage emphasized that Blake was an "ex-convict" and had been arrested 14 times.

Richard Coakley (July 30, 1965). Coakley, a 23-year-old white male, was shot by an off-duty officer while Coakley and a partner, Terrance Colton, were robbing a bar at 1:15 a.m. They had guns and took money from customers and the cash register before Patrolman Herman Boritski, who was socializing with friends, stated that he identified himself as an officer and shot both men. Coakley died at the hospital, and Colton survived with two bullet wounds in the back. The newspaper coverage emphasized that both men were "ex-convicts."

Donald L. Gumbleton (Sept. 6, 1965). Gumbleton, a 25-year-old white male, was shot seven times and killed by multiple DPD officers after he allegedly committed three holdups and then tried to escape the police chase by commandeering a car at gunpoint and forcing the driver to flee in a high-speed chase. Gumbleton exchanged shots with police officers in a foot chase before jumping into the car and then, when surrounded by police, shouted "come and get me" but did not fire his gun as the officers fired at least a dozen rounds. Gumbleton had recently been discharged from the state mental hospital after a two-year stay and was an alleged narcotics addict who told the driver of the car that he did not want to be caught and sentenced to life in prison.

Richard Pieciak (Oct. 10, 1965). Pieciak, a 22-year-old white male, was killed by a single bullet in the neck fired by Patrolman Paul Ninelist while he was fleeing on foot after a high-speed car chase in Northwest Detroit. Pieciak evaded officers for two miles on a motorcycle before they caught him at a drive-in. He was on parole, which likely explains what happened next. Once placed in the scout car, Pieciak allegedly grabbed Patrolman James Scanlon's gun and ran toward Rouge Park. Patrolman Ninelist fired at Pieciak while he was fleeing and no longer an immediate threat, but still had the officer's gun. Around 300 white youth who witnessed the slaying engaged in a spontaneous protest around the squad car and had to be dispersed by the Tactical Mobile Unit. Police Commissioner Girardin publicly acknowledged that the shooting of the fleeing and young white man required an investigation, and Prosecutor Samuel Olsen exonerated the officer for the homicide.

Willard Redding (Nov. 27, 1965). Redding, a 46-year-old African American male, was shot and killed by Patrolman Howard Allen, a Black officer, outside an East Side laundromat at 4:30 a.m. Redding, a private security guard, was wearing a gun in a holster and objected to Patrolman Allen's request to see his permit. The two men began to scuffle, and Redding allegedly pulled out his gun. Patrolman Allen fired six shots and killed him.

Noel Vandewiele (July 8, 1966). Vandewiele, a 22-year-old white male, was shot and killed while fleeing by Patrolman Francis Wypch of the Tactical Mobile Unit. Vandewiele was suspected of robbery at a service station, and Ptr. Wypch and his partner gave chase. The officers claimed that Vandewiele fired two gunshots at them while trying to escape, and so Wypch emptied his revolver, killing the suspect.

Sources:

Newspaper and other sources for individual homicides are in the pop-up boxes on the map

"Call for Probe of Olsen's Acts," Michigan Chronicle, June 5, 1965

Additional James Sabra coverage: Michigan Chronicle, July 10, 17, Aug. 14, 1965

NAACP Detroit Branch Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962 revision), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library