School Criminalization

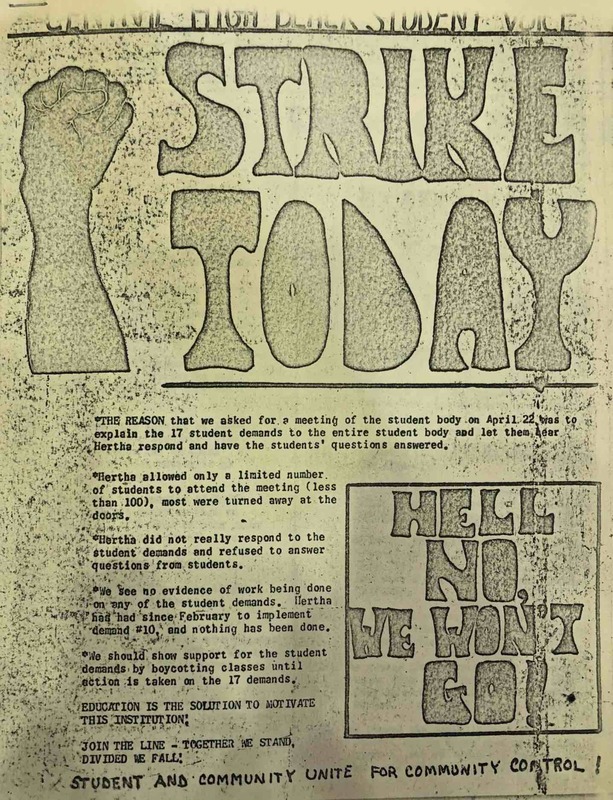

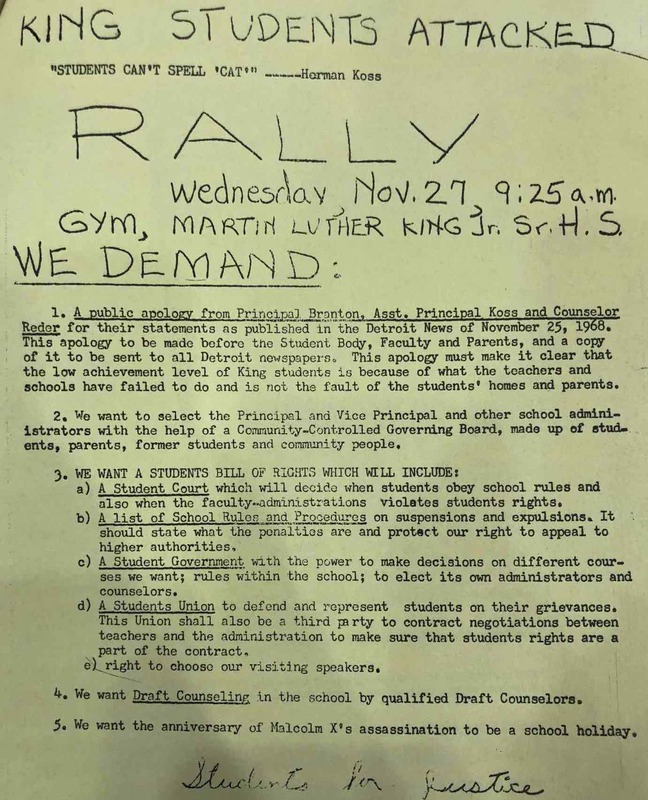

The Detroit Police Department relentlessly expanded its criminalization and mistreatment of African American youth after the 1967 Uprising, including inside the public schools of the city of Detroit. The public education system, and especially the high schools, were sites of intense racial conflict in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many African American students who participated in the civil rights and black power movements became politically mobilized around issues of racial injustice inside the schools themselves, and by the early 1970s a coalition called Black Student United Front had chapters in all 22 of the city's high schools. The administrators of the Detroit Public Schools (DPS) repeatedly criminalized black students for engaging in political protests and called on the police to arrest them when they engaged in strikes and other confrontational activities. DPS principals also worked closely with the Detroit Police Department to station officers inside schools, a practice that had begun in the mid-1960s and expanded rapidly over the next decade, the origins of what is now called the school-to-prison pipeline. Black student groups demanded the removal of police from their schools, as in this list of strike demands in 1970 by the Central High Black Student Voice (right). As part of the black power/community control movement, the Central High organization called for changes in the curriculum to promote African American history and culture as well as an end to the constant harassment of their movement by school administrators and police.

The racial integration of public schools and surrounding neighborhoods also intensified the conflict inside educational institutions during the late 1960s and early 1970s, as white students and surrounding white communities often responded to the presence of black students with violence and the police generally took the white side of such confrontations. The city of Detroit experienced rapid racial transition during this era, with hundreds of thousands of white families fleeing to the suburbs, and black families moving into formerly segregated neighborhoods and therefore attending the local schools. Then in the spring of 1970, the Detroit Board of Education passed a limited school integration plan that prompted a massive backlash from the remaining white residents of the city and led to further attacks on black students inside, and en route to and from, newly integrated schools. By that year, the overall DPD enrollment was almost two-thirds African American, leading to a sense of being under siege by the white population that was clustered in the northeast and northwest parts of Detroit in neighborhoods that were often still 100% segregated. Racial tensions escalated even more after the NAACP secured a 1971 court order requiring the racial integration of public schools throughout the Detroit metropolitan region, leading to widespread antibusing protests in white suburbs as well, but the Supreme Court overturned this ruling in the 1974 decision of Milliken v. Bradley. Overall, this was an incredibly volatile and often violent time period in the Detroit public schools, and in many cases the Detroit Police Department contributed to the racial violence rather than enforcing the law fairly.

Student Political Mobilization and Police Repression

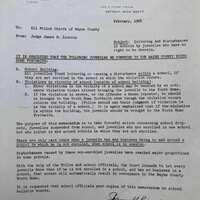

Pressure to install police officers inside Detroit public schools began building in the mid-1960s as part of the broader get-tough on crime movement of that era. At first, conservative politicians such as Wayne County Prosecutor Samuel Olsen led the charge for a permanent police presence inside schools with significant black enrollment, falsely hyping a wave of violence by African American teenagers, whom he and his allies labeled "young hoodlums," "juvenile terrorists," and "punks who are running wild." The liberal Cavanagh administration was initially resistant, and Commissioner Ray Girardin said in 1964 that the DPD did not have the manpower to "keep an army of officers at the schools" and that "such a program would be a violation of the educational process." Instead, Girardin authorized police to use their discretion to intervene inside public schools when alerted by administrators, including using the recently passed anti-loitering law to detain juveniles who were near school grounds but not enrolled or just not in class when they were supposed to be. The DPD also permitted precincts to work directly with public high schools when the principal requested an expanded police presence, the opening wedge to permanent status. In 1968, Judge James Lincoln of the Juvenile Court expanded this policy of discretionary criminalization by requesting that police also arrest juveniles for loitering inside school buildings whenever they were "causing a disturbance" and also to arrest drop-outs, truants, and suspended students if seen in or near a school (right).

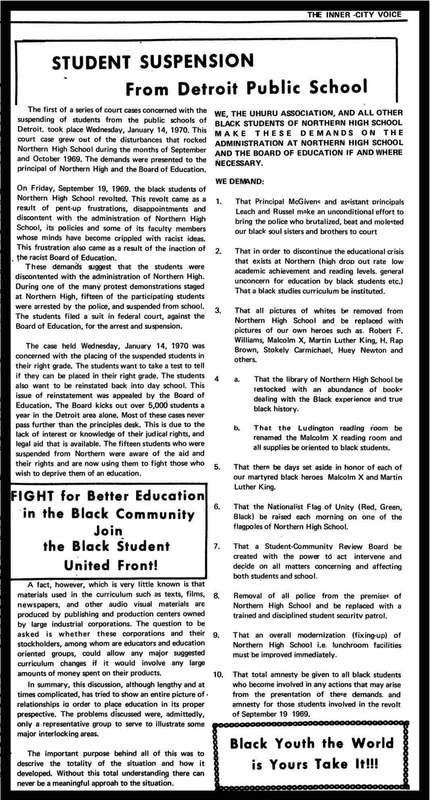

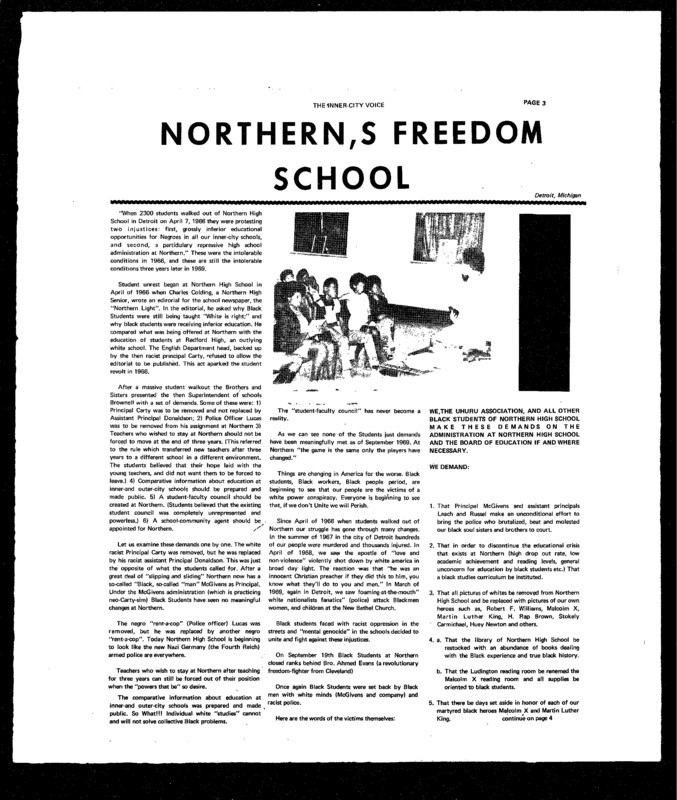

In the mid-1960s, Northern High School, which had an overwhelmingly African American enrollment, made such an arrangement with the local DPD precinct to station a police officer, Barney Lucas, inside the facility full-time. Lucas was an African American officer, and the decision had widespread support from black civic groups and the Michigan Chronicle, but not, as it turned out, from a significant number of black students themselves. In April 1966, around 2,300 African American students at Northern High School staged a three-week civil rights walkout. They made two main demands: improvement of the terrible and inferior educational opportunities in their segregated high school, and the removal of Officer Lucas from the facility. The students charged Lucas with a reign of fear and terror that involved imposing discipline with extreme brutality and often random violence. DPS administrators agreed to remove Lucas but also expanded the police presence at Northern High School over the next few years. This eventually led to another walkout by around 600 black students in fall 1969, which demanded "removal of all police from the premises of Northern High School and be replaced with a trained and disciplined student security patrol" (left).

The Detroit Police Department responded to the 1969 walkout by the Black Students of Northern High School with force, beating protesters and arresting fifteen African American youth, and the school administration also suspended a number for their political activities. After police attacked black students with their nightsticks, a few threw rocks and bottles at a police car, leading to more arrests for inciting riot, felonious assault, and malicious destruction of property. The Northern High students responded to the criminalization of their political movement by challenging their arrests in court and issuing an updated set of demands inspired by the black power movement for community control. They demanded that all discipline involving students be conducted by a Student-Community Review Board that would also evaluate the actions of teachers, administrators, and police. The list of demands also included a black studies curriculum, the replacement of images of white "heroes" with black revolutionaries on the walls, immediate modernization of the inferior facility, and amnesty for all protesters. The #1 demand called for:

Radical black organizations worked closely with the Northern High students, including the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and UHURU, which had helped lead the protests against the DPD for Cynthia Scott's murder back in 1963. These groups also started a Freedom School for the suspended Northern High students and others who were boycotting the institution, about 200 total (gallery, below left).

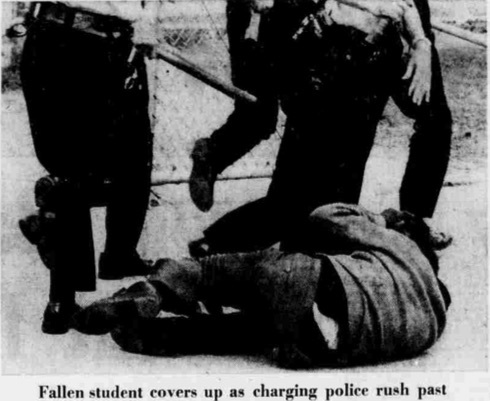

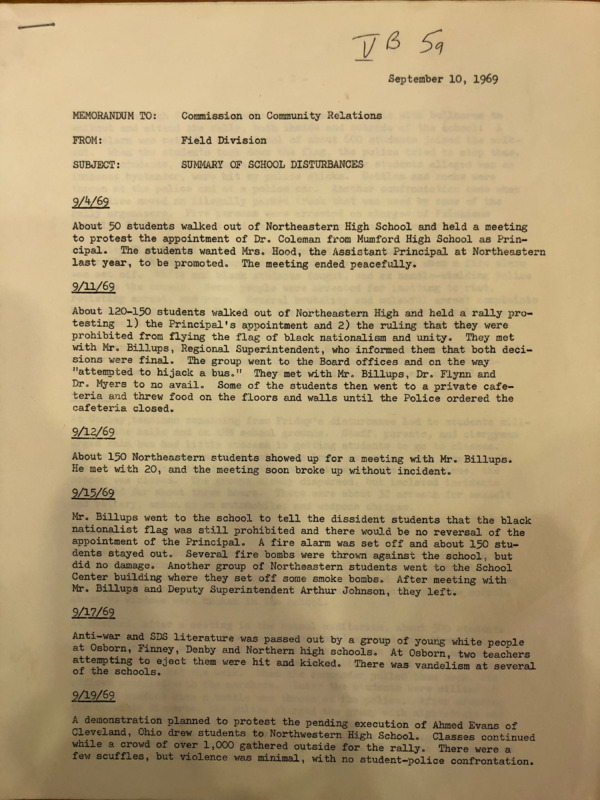

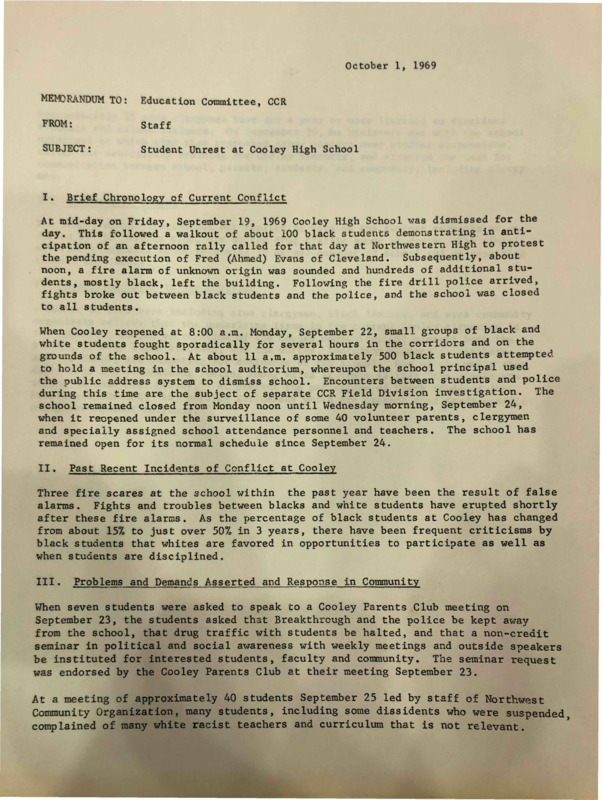

The wave of student protests spread to several other Detroit high schools in the fall of 1969 as part of a conscious black nationalist youth movement. The public school system generally responded by rejecting student demands, censoring their political expressions, and calling the police to handle the protests. Some of the worst violence happened at Cooley High School, which was in an area undergoing rapid white flight and where the enrollment shifted from 15% to 50% African American in two years. After fights broke out between white and black students, the police intervened while wielding axes and other weapons. A number of black students filed charges of police brutality with the Citizen Complaint Bureau after the first incident, and then a few days later the police made 32 more arrests of Cooley High students. African American students at Cooley and elsewhere accused the police of only targeting and arresting black students when racial incidents between black and white students broke out in the tensely integrated schools (gallery, below right).

On Sept. 23, 1969, DPD officers in riot gear attacked a Black Student United Front march by 500 teenagers from several different senior and junior high schools who were protesting police violence as well as racism in the school system. The Detroit Free Press coverage blamed the black students for causing the violence by breaking windows and throwing bricks and bottles. The newspaper also portrayed the event as a black youth riot that the "club-wielding police" had to control, rather than a civil rights protest march as the Detroit Commission on Community Relations labeled it in its investigation (below, second from right). The Free Press attributed the violence to the influence of the Republic of New Africa, the black nationalist group targeted by police in the recent New Bethel Incident. According to the DCCR, however, the main violence happened because "the police charged the [black student] group with nightsticks and riot batons."

Extreme Police Brutality at Post Junior High (1968)

The Detroit Police Department frequently brutalized and arrested African American youth who engaged in civil rights activism inside schools during this time period. Some of the worst police violence took place in March 1968 at Post Junior High School, where the enrollment was 97% African American. Hundreds of Post students staged a walkout to protest racism by teachers and the white assistant principal (the principal was African American) along with the generally dilipadated conditions of their segregated facility. During the initial walkout on March 12, the DPD mobilized with rifles and riot control gear and:

- One white DPD officer racked and pointed a shotgun at a group of black students, because he "just wanted to scare them."

- A second white officer pulled his revolver on the terrified students when they started running away.

- Three more white officers began punching a different group of black students and assaulted a teacher who tried to defend them.

- Another group of white officers harassed black students on their walk home, calling them racial epithets.

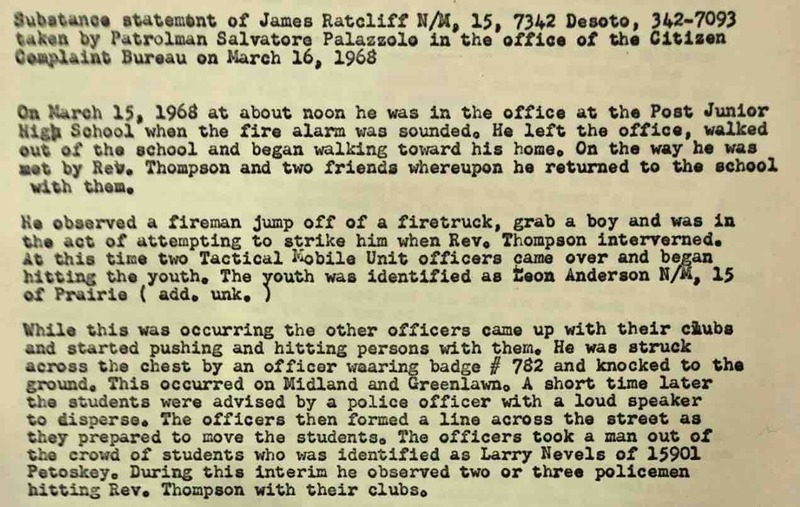

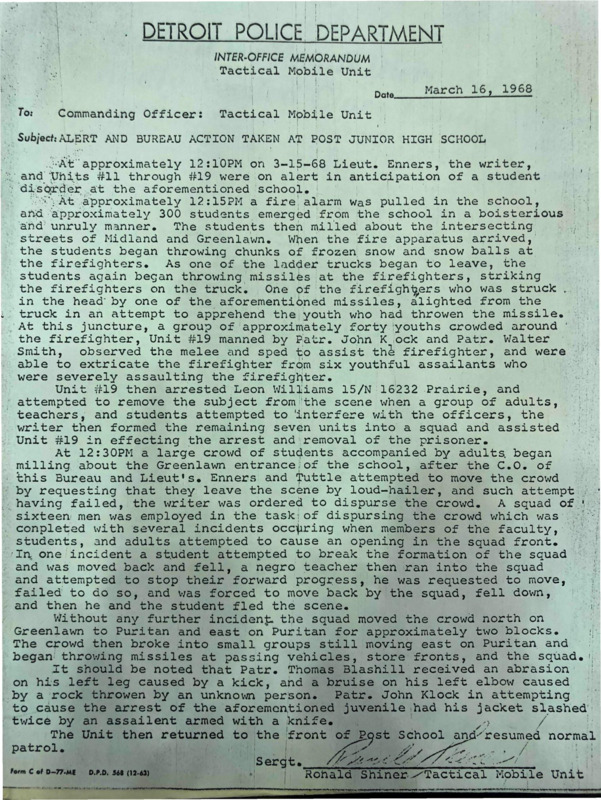

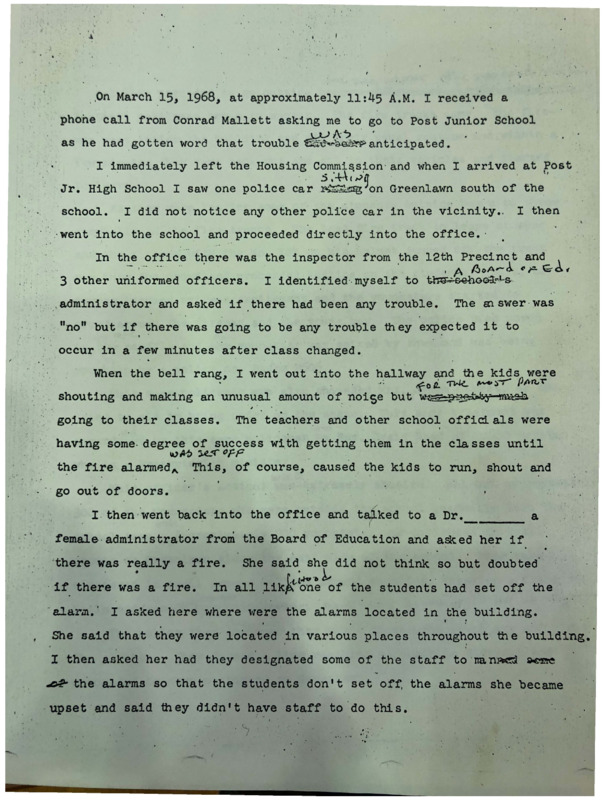

The black students organized a second walkout on March 15 after the administration refused to consider their demands. Before and during this event, the Tactical Mobile Unit, which had responsibility for "crowd control" in riots and political demonstrations, mobilized in a show of force against the middle school students. The official TMU report stated that the "boisterous and unruly" students had provoked the police on March 15 by "throwing missiles" and committing assaults. According to dozens of witnesses, this is what really happened:

- In the morning, three officers grabbed and interrogated a 14-year-old black student about whether a walkout would occur and threatened to take him to juvenile detention.

- The DPD arrested a black parent who was there to support the students in their protest.

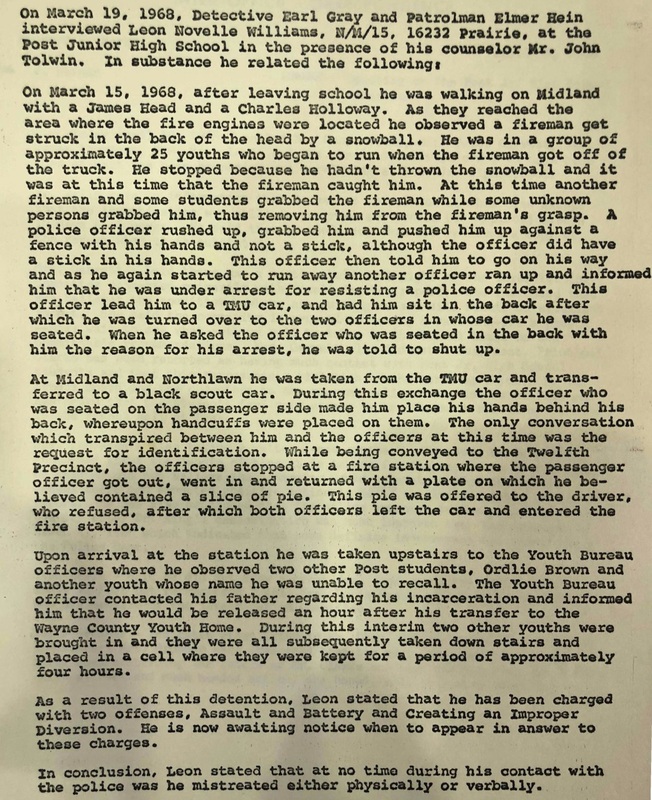

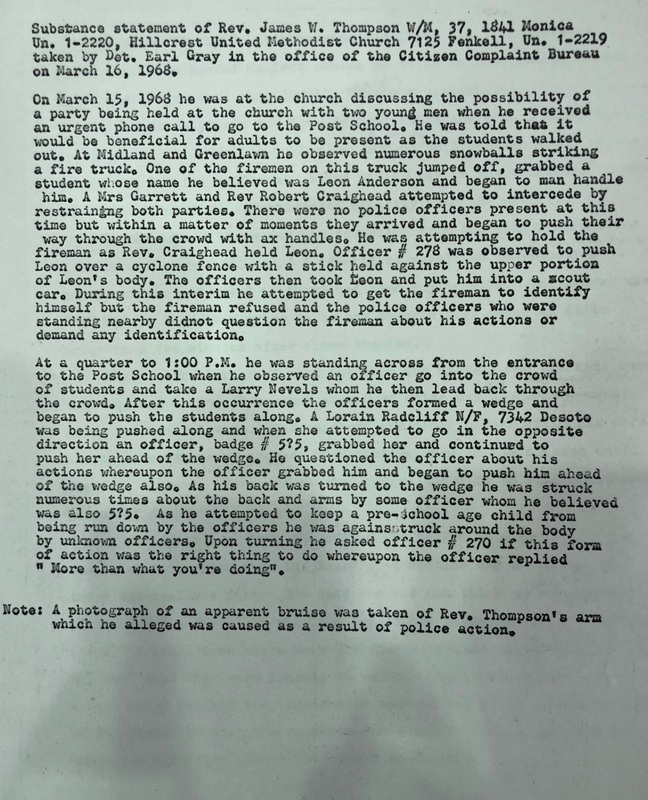

- A white firefighter violently attacked a random 15-year-old black student, Leon Williams, after a group of different youth threw snowballs at his fire truck, which was there because someone pulled a fire alarm.

- Additional TMU officers assaulted Leon Williams, threw him over a fence, and arrested him for assault.

- TMU officers waded into the crowd of black students and parents and attacked many people with clubs and nightsticks.

- When several black mothers protested the violent attacks, the police officers beat them as well.

- TMU riot police in phalanx formation began clearing the street and "striking everyone on the scene," including students, parents, supportive black teachers, and a white minister (Rev. James Thompson) who was there to calm tensions.

- TMU officers chased after black students who ran away and beat a number of them ten blocks or more from the school grounds.

The TMU arrested six black students, including Leon Williams, and fabricated an account that the group had precipitated the incident by "throwing missiles" and "severely assaulting the firefighter" (below left), which dozens of eyewitnesses accounts contradicted.

The day after the police assault, a group of the African American victims filed grievances against the officers to the Citizen Complaint Bureau. Eleven area ministers from black and white churches formed an ad hoc committee and asked DPD commissioner Ray Girardin:

Rev. Albert Cleage, a prominent black radical, denounced the DPD's "storm trooper tactics" and demanded the immediate suspension of all of the officers involved. At an emergency PTA meeting, five hundred outraged black parents insisted that the Detroit Police Department eliminate "the presence of unjustified number of police in the area" of Post Junior High, which they blamed in part on the hostility of nearby segregated white neighborhoods to the presence of black residents nearby. The PTA also pressured the school principal to remove DPD officers stationed inside the junior high school, which ultimately did happen and had the long-term effect of curtailing much of the violence. As a community-based alternative, the PTA stationed black mothers inside the building and black fathers on the streets outside, to protect their children from police violence and address youth issues without involving law enforcement.

Read more about the police violence at Post Junior High, and the DPD denial of wrongdoing, in the gallery below.

Criminalizing Black Youth Politics vs. White Communal Violence

The Detroit Police Department operated as an extension of the white community, criminalizing black youth for engaging in political activity through their schools and generally intervening on the side of white students during episodes of racial conflict in facilities experiencing tensions and violence because of school integration and white backlash. These are just four of the many incidents that took place during the tumultuous years of 1969 and 1970.

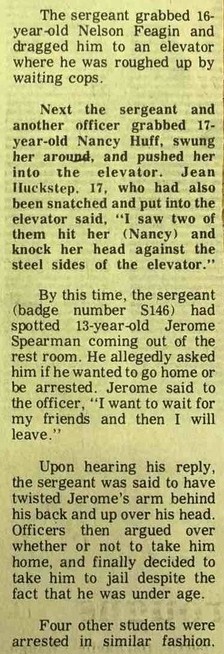

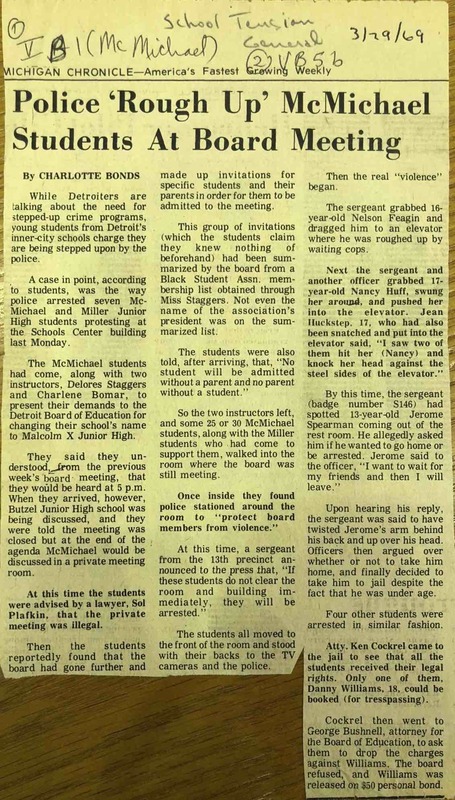

DPS Headquarters (spring 1969): In a March 1969 incident (right), a group of junior high students from the Black Student Association attended a board of education meeting with two of their teachers to request that their school's name be changed to honor Malcolm X. The board refused to let them speak, which was illegal, and called the police to "protect board members from violence," presumably because the teenagers were African American. The students protested by refusing to leave the room when ordered to do so without cause. The DPD officers punched, dragged, and generally brutalized the students in response. They smashed the head of a 17-year-old female against the steel doors of an elevator. They dragged a 16-year-old male into the elevator to beat him out of sight of witnesses. They roughed up and arrested a 13-year-old boy and then took him to adult lock-up, in violation of policy. In total the DPD arrested 7 teenagers from the Black Student Association for seeking to exercise their legal rights to address the Detroit Board of Education. The Board of Education pressed charges against the only non-juvenile in the student group, an 18-year-old, for trespassing.

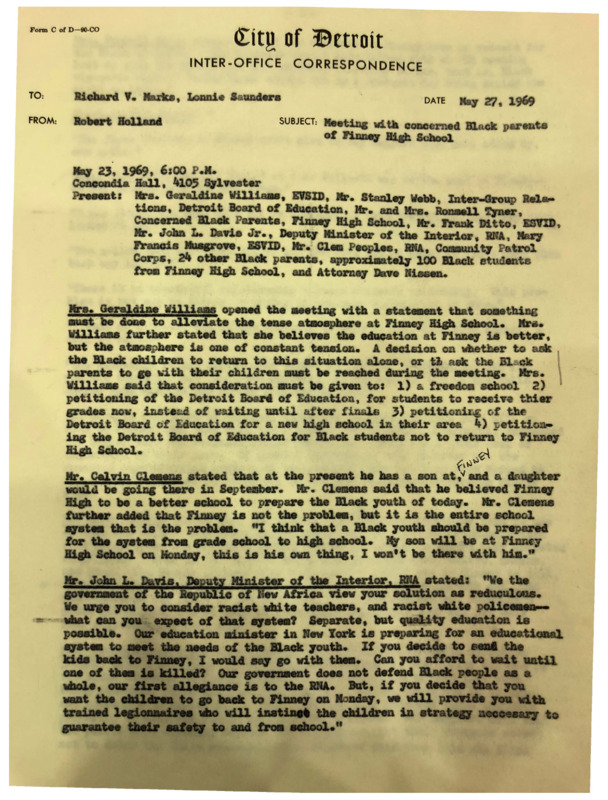

Finney High School (spring 1969): Black students and their parents also charged that the DPD refused to protect them from white violence inside schools that were undergoing racial integration. In May 1969, the Detroit Committee on Community Relations held a conference with 100 African American students from Finney High School, along with some of their parents and community activists from the East Side Voice of Independent Detroit. Finney was located in a racially transitional area where a right-wing organization called Breakthrough had a particularly strong presence and had been encouraging violence by white students against their black counterparts. Black students recounted white police officers declining to respond to their complaints of attacks by white students and telling them, "you better get the hell out of here, we can't hold them back any longer." Some black parents were keeping their children out of the school and predicting that a black student would be killed sooner or later. When the police finally did arrest some white Finney students, they had an arsenal of "hand grenades, knives, chains, and guns." But when members of the East Side Voice of Independent Detroit showed up at the school to protect their children, the police arrested them as well. The DCCR investigation (below) concluded that white students were the aggressors and that the DPD had to become capable of resisting white community pressure in order to enforce the law "equally" at Finney High School.

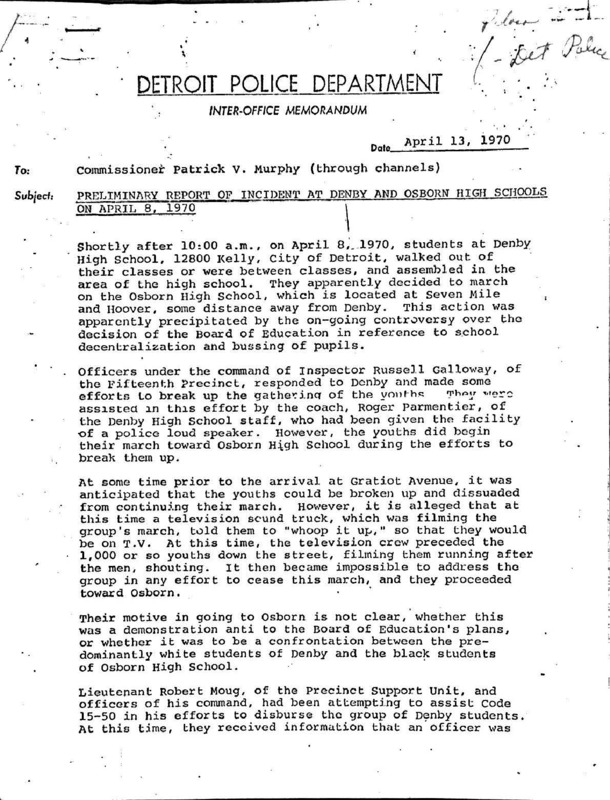

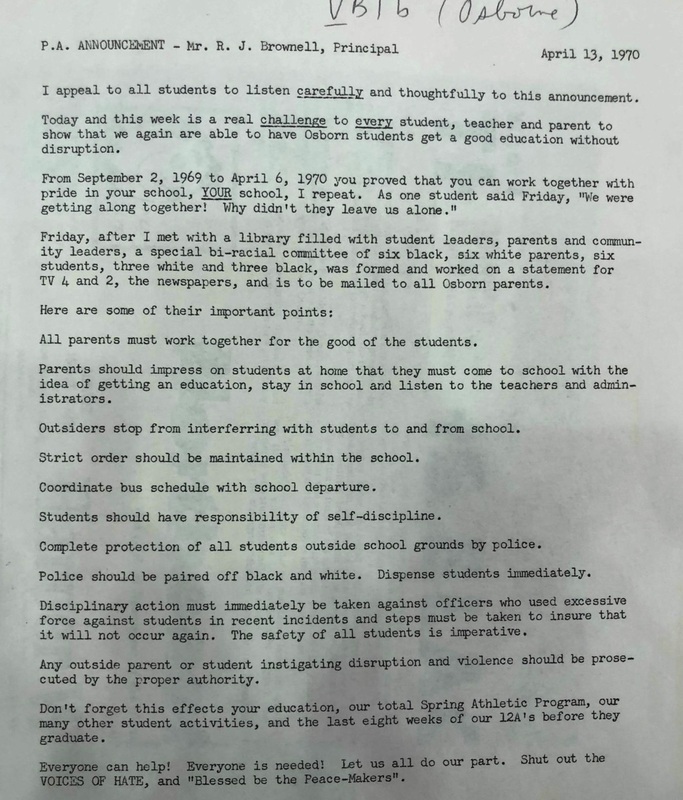

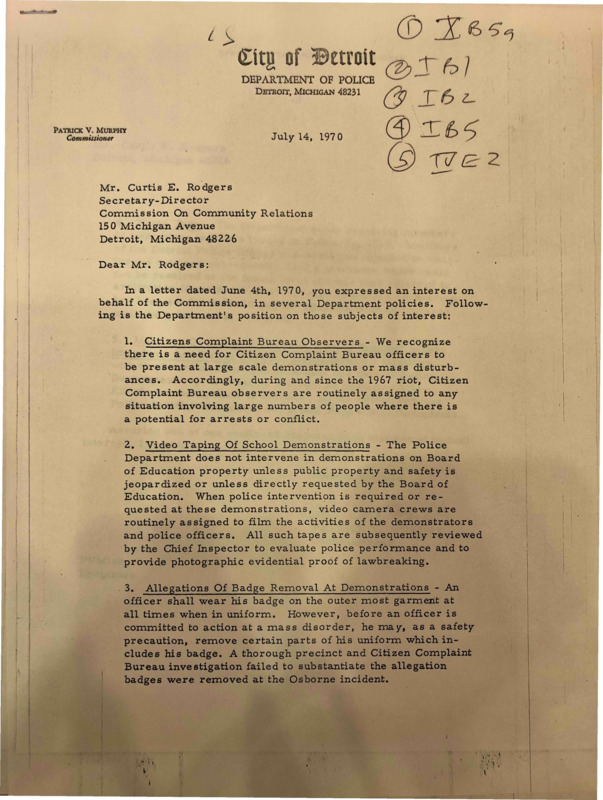

Osborn High School (spring 1970): These racial tensions worsened in 1970 after the Detroit Board of Education, under pressure from civil rights groups, adopted a relatively modest school integration plan and white backlash escalated dramatically. In April, a large group of around 1,000 white students from Denby High School, located in the segregated part of Northeast Detroit, began marching three miles to Osborn High School to confront its African American student population, apparently because the integration plan involved exchanges between the two schools. The DPD deployed riot police to contain the racial violence, and Osborn High administrators sent the black students to the bus stop to return home early to avoid trouble. DPD officers then arrested several of these African American youth who were standing outside Osborn High, claiming that they were throwing rocks at cars. DPD officers beat several black students in front of news television cameras and made 14 arrests. At least ten African American teenagers, half male and half female, filed allegations of police brutality to the Citizen Complaint Bureau of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, charging that police officers beat, kicked, and punched them (right). The black students and their families also charged the police with racial favoritism by not arresting the white students who had caused the conflict, and they requested that Osborn High be assigned an all-black police patrol to protect them from white community violence. The DPD's internal investigation (below) rejected cleared the officers by finding that the black students had precipitated the use of force by resisting arrest and that "the police response and activity as the Osborn High School was generally proper and appropriate."

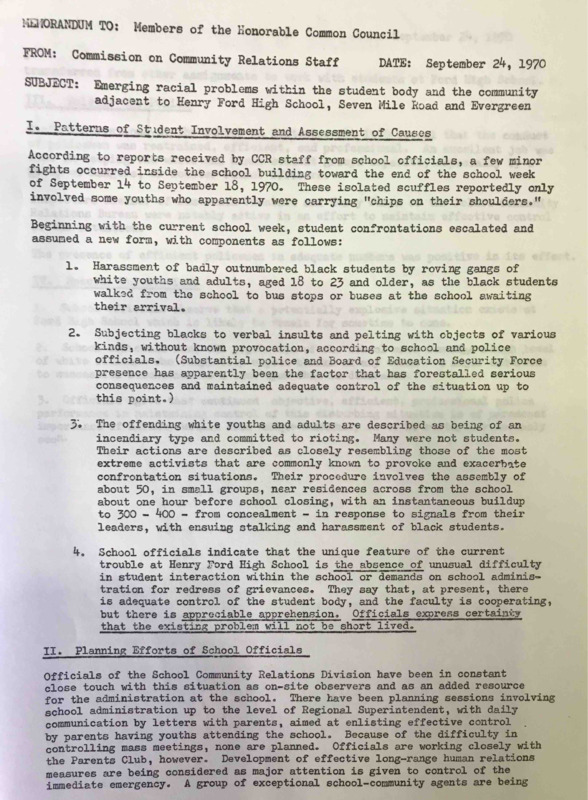

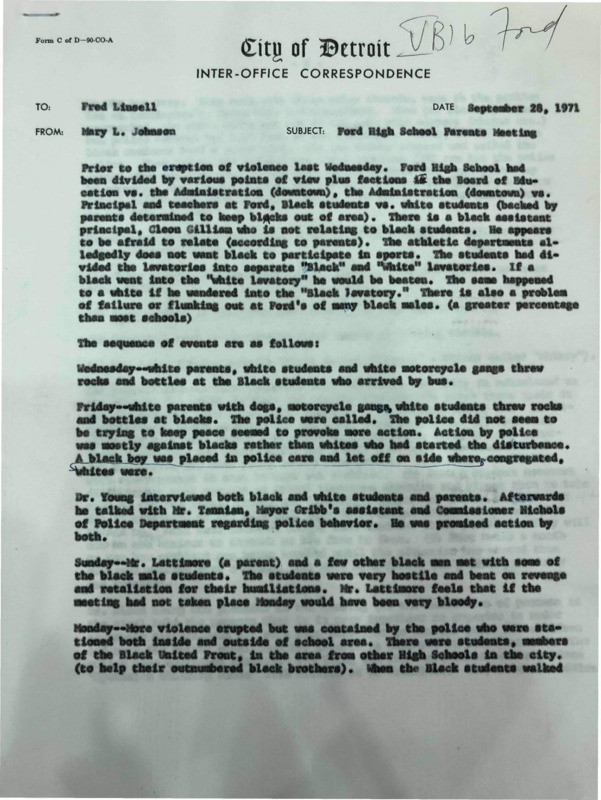

Henry Ford High School (fall 1970): Henry Ford High was located in an intensely segregated section of Northwest Detroit, with significant white hostility to the board of education's limited integration plan that transferred a small number of black students in 1970. A DCCR investigation reported harassment without provocation of "badly outnumbered black students by roving gangs of white youths and adults," including racial epithets and thrown projectiles by white members of the surrounding neighborhood as the black students arrived and departed on the school buses. The DCCR and public school officials blamed the large number of white extremists who lived in the area and refused to accept any presence of African Americans in their schools or neighborhoods. In this episode, unlike a number of others, the DCCR praised the police for their professionalism in protecting the black students from even greater harm. The DPD arrested 25 white students and adults, along with 8 black students who were defending themselves, a different racial ratio than had been typical during school violence episodes in recent months and years.

Read more details about all of these incidents in the gallery below.

Permanent Police Presence in Detroit Public Schools

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an increasing number of principals and local school committees authorized the permanent stationing of police officers in their schools. While not yet a formal DPD policy, the decentralized and discretionary rules of both the police department and the Detroit Board of Education allowed individual schools to arrange with precinct commanders for regular patrols and the stationing of one or more officers inside the buildings on an ongoing basis. The practice started in the all-black schools, where administrators believed that a substantial percentage of black youth were criminally inclined, but spread quickly to the recently integrated schools as well. Racial conflict between white and black students was a primary motivator for this development, in order to keep the peace, although (as described above) many black students and parents argued that the police presence made the situation worse and not safer and endorsed community-control alternatives.

The permanent presence of police officers had the effect of criminalizing typical adolescent behavior and mischief and elevating fights, truancy, disrespect for authority, in-school disturbances, and other such activities to the level of criminal conduct. Many DPD administrators and most DPD officers also criminalized the Black United Student Front and other politically active African American students, viewing them as trouble-makers and considering them as equally or even more responsible for the in-school violence that groups of white students and other adults from white communities often clearly provoked.

By 1970-1971, white violence against black students in the integrated junior and senior high schools had become so extreme and common that the Detroit Police Department faced substantial pressure to control the white community rather than continue its default approach of criminalizing, beating, and arresting black students during outbreaks of intraracial unrest. Whether or not this actually happened depended upon the discretionary decisions of the officers on the scene. Two examples, selected from the dozens of episodes of racial conflict and police intervention in the Detroit Public Schools during the early 1970s, show these divergent outcomes.

- Osborn High (March 1971): Significant racial conflict began in the spring of 1970 after approval of the integration plan. The principal established a biracial committee of students and parents to keep the peace and urged white adults to stop attacking and harassing black students, who represented about one-sixth of the total enrollment, on their way to and from school. After the white anti-integration march described above, the principal called for integrated police units to protect black students, prosecution of police for excessive force, and prosecution of outsiders who incited violence (below left). Tensions continued and then in March 1971, 50 white students roamed through the school attacking black students, apparently because the principal allowed them to put up a "Black Is Beautiful" display. The white students then threw rocks at the police who arrived to suppress the disorder. The principal closed the school indefinitely and blamed "white rage against the blacks," and in this extreme situation most of the students arrested by police were white. But the DCCR investigation also criticized the police and school policy of always sending the black students home on buses when white students attacked them, "treating them as an outside force," while allowing white students and community members to congregate outside school buildings and only arresting them in extreme situations.

- Henry Ford High School (Sept. 1971): A city investigation found that the white community was "determined to keep blacks out of the area," that the sports teams would not allow black students attending under the new integration plan to participate, and that hostile white teachers were trying to flunk black students out of school. At the start of the new school year, white parents and students "threw rocks and bottles at the black students who arrived by bus." The DPD officers who deployed took the side of the white community and "did not seem to be trying to keep the peace; seemed to provoke more action." The police arrests and crackdowns were "mostly against blacks rather that whites who started the disturbance" (below second from left).

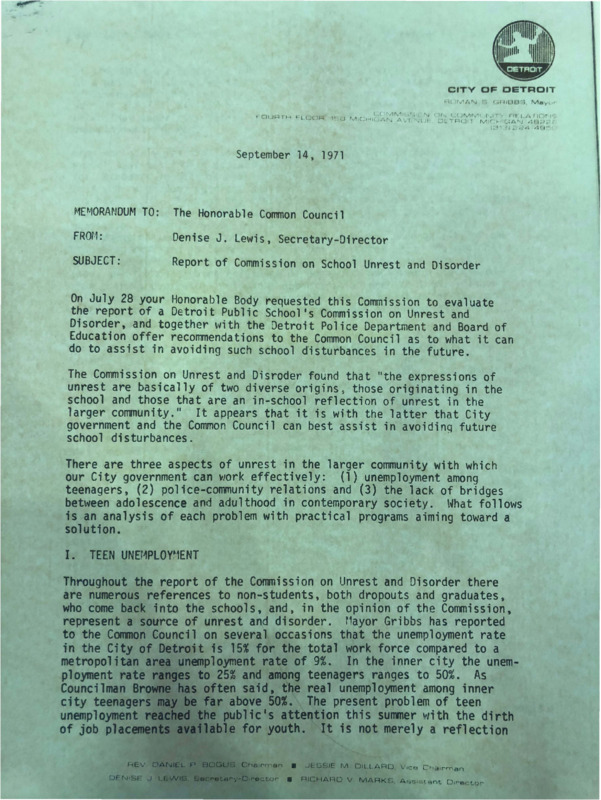

The Gribbs administration established a Commission on School Unrest and Disorder in response to these events, and its report found that the 89% white police department, including many officers who lived in the suburbs, "has a credibility gap in today's high schools, especially those with large black enrollment." The Detroit Commission on Community Relations drafted the committee report, which recommended racial sensitivity training for police officers assigned to schools, faster diversification of the DPD, and enforcement of the city residency requirement. The commission also urged the Detroit Public Schools to integrate African American history and culture into the curriculum and terminate teachers and administrators who operated in openly racist ways (below right). In a separate report, the DCCR criticized the practice of police officers who removed their badges and other identifying information while controlling protests and demonstrations (which the DPD termed "mass disorders"), thereby making it impossible for students to file complaints against specific officers. Note that in the most important legacy, the white and black liberals in the DCCR did not call for the removal of police from public schools, but rather accepted their presence as necessary and urged only that the in-school officers receive sensitivity training and that a greater number of them be nonwhite.

The Black United Student Front and its affiliated groups took a much more radical stance, repeatedly demanding the removal of police from public schools entirely. In 1971, students at Cooley High, which had undergone considerable racial conflict, nevertheless called for "an end to the use of police to settle disputes within the schools." Radical youth in the Detroit Student Mobilization Committee also demanded the end of the police presence in schools in a High School Bill of Rights released in 1971.

Sources

Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press, April 19, 1966, Sept. 24, 1969, April 9, 1970, March 19, 1971

Michigan Chronicle, March 29, 1969

David Gracie, “The Walkout at Northern High,” New University Thought (May-June 1967)

Ivory D. Williams, “Detroit’s Northern High School 1966 Walkout,” Lecture, Third Thursday Speaker Series, Detroit Historical Society, September 20, 2018

Inner-City Voice, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

The Black Power Movement: Papers of the Revolutionary Action Movement, 1962-1996, ProQuest History Vault

Detroit Student Mobilization Committee, “High School Bill of Rights,” March 1971, Box 55, Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Note: Some of the research from this page comes from newspaper and archival research cited in two undergraduate papers written in 2019 by contributor Robert Joseph, "Liberalism and the Institution of School Policing in Detroit, 1964-1968," and "'The Problem of Outsiders': Criminalization, Brutality, and Political Repression, 1968-1972." Other research drawn from the extensive investigations by the Detroit Commission on Community Relationsis from documents in boxes in Part III, Series 5, not specifically reproduced on this page.