Patterns of Police Brutality and Misconduct

These interactive maps display 147 allegations and incidents of brutality and misconduct made by civilians against the Detroit Police Department between the years 1964 and 1966, identified by our research team through archival documents and newspaper reports. The incidents appear on maps of racial geography and of neighborhood income (visit this section's StoryMap to view these incidents in terms of Detroit's street-level landscape). For comparative purposes, police homicides and non-fatal shootings of civilians are also included on these maps, but they are analyzed in detail on the next page.

Click on the dots for pop-up boxes with more detail on each incident and the source citation. Scroll down this page, below the maps, for featured stories on key cases.

- Black dots (99) = Police Brutality

- Brown dots (48) = Police Misconduct

- Red dots = Police Homicide of Civilian

- Yellow dots = Police Shooting of Civilian (nonfatal)

All Police Incidents/Racial Geography: Brutality, Misconduct, Shootings and Homicides of Civilians (1964-1966)

Note: blue = African American residence; green = white residence. Zoom the map to analyze particular areas.

All Police Incidents/Income Level: Brutality, Misconduct, Shootings and Homicides of Civilians (1964-1966)

Note how most incidents took place not just in African American neighborhoods but in the poorest areas.

Key Findings

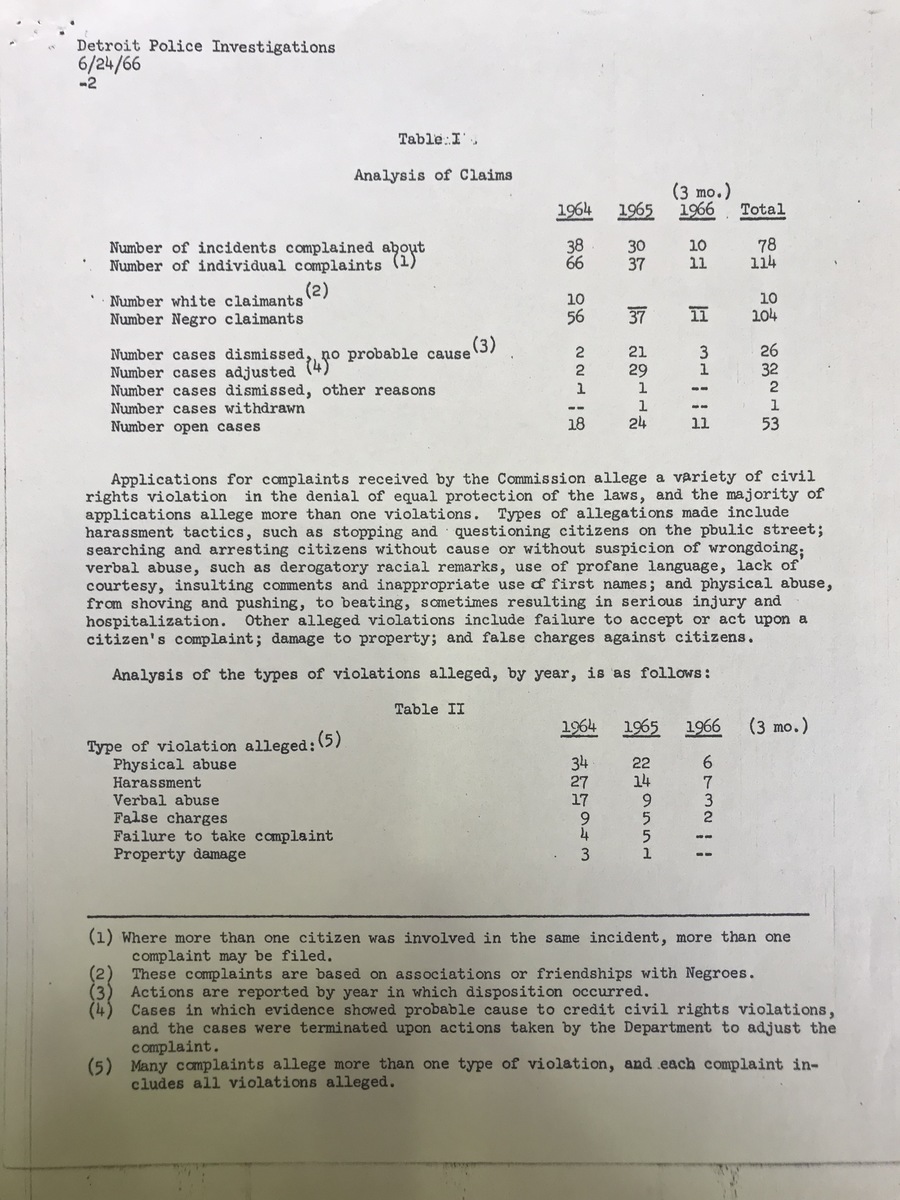

- Roughly 94% of the complaints filed against the almost exclusively white Detroit Police Department between 1964 and 1966 were made by African American citizens.

- The vast majority of filed police misconduct and brutality complaints occurred in the poorest African American neighborhoods, or along the color line between neighborhoods mainly populated by African American and white citizens. Incidents also clustered in the downtown business district and along Woodward Avenue.

- The percentage of brutality complaints from the poorest and most segregated Black neighborhoods (dark blue census tracts) escalated during the mid-1960s, whereas a much higher ratio of complaints during the decade before 1964 originated from middle-class African Americans based on incidents that occurred in racially transitional areas along the color line. This likely reflects both the ways in which the liberal "war on crime" flooded lower-income Black areas with militarized police units and the role of newer grassroots Black Power organizations in mobilizing campaigns against police brutality in these neighborhoods.

- The number of complaints recorded increased over the three-years period as a result of the creation of the Citizen Complaint Bureau, and the continued work of civil rights organizations that were advocating for police reform, but the Detroit Police Department controlled the complaint investigation process and found almost all of them to be 'unjustified.'

- Most of these incidents violated the DPD's own permissive policies on the use of force in making arrests, and/or the DPD's policy on "illegal arrests," for which officers had civil liability (see policy at right). Excerpt:

Case Studies of Police Brutality

This section profiles three incidents of police brutality included in the above maps. The police beatings of Edward Dowdell, Howard King, and Clarence Vesper are merely three stories of many.

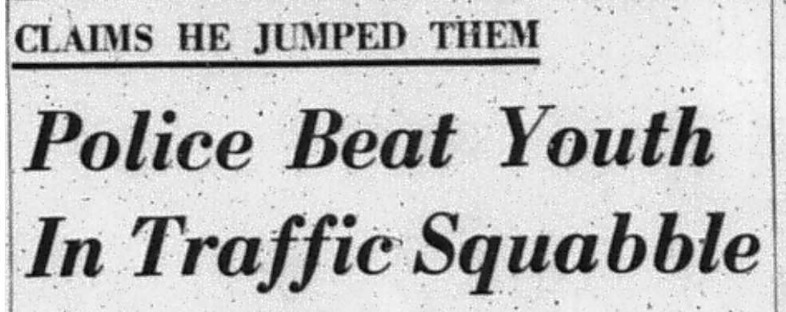

Edward Eugene Dowdell, a 20-year-old African American male, was assaulted by police officers on December 1, 1964, near his home on Sheridan Street in downtown Detroit.

That night, Dowdell and a friend took their girlfriends on a double date. After they dropped their girlfriends off, they drove separately toward Sheridan Street, where they both lived. Dowdell's friend turned down an alley, while Dowdell continued straight. A police scout car pulled Dowdell over for no apparent reason, and the officer inside asked Dowdell where his friend went. When Dowdell said he didn't know, the officer reportedly said, "We'll have to give you two tickets, one for yourself and one for him."

Dowdell objected to the unjust tickets, and an argument ensued. His lawyer, appointed by the NAACP, told the Michigan Chronicle that one of the officers hit Dowdell in the face, while the police claimed that Dowdell punched one of the officers. Panicked, Dowdell fled. The officers caught up with him on the corner and beat him until he was semi-unconscious.

Dowdell recalled hearing the conversation of the officers deciding what they should do about the incident while he sat in the police car. The officers worried that Dowdell's friend might have witnessed the scene, so they decided to claim that Dowdell began the fight and threw the initial punch.

Dowdell was left in serious condition at Detroit Receiving Hospital where a neurologist performed surgery on his head. Dowdell's right wrist was partially paralyzed, and his head, knees, elbows, and ankles marked with visible acts of violence. The police department charged Dowdell with assault and battery against a police officer--a common strategy when faced with allegations of misconduct--and set a trial date for when he healed.

The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's main African American newspaper, reported the beating in two separate editions and told two different stories. Compare Dowdell's story with the police officers' story by clicking the newspaper clippings.

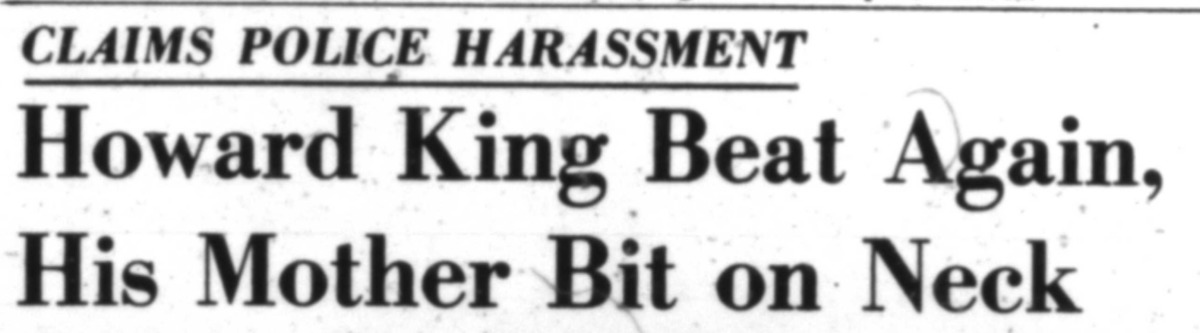

Howard King, a 16-year-old African American male, was involved in several separate police incidents between 1965 and 1966. King lived near downtown Detroit in a mostly white, low-income neighborhood called North Corktown, with his mother, Mary Lee King. They are cited to have lived at 3002 Harrison and 1731 Butternut, two addresses very close together.

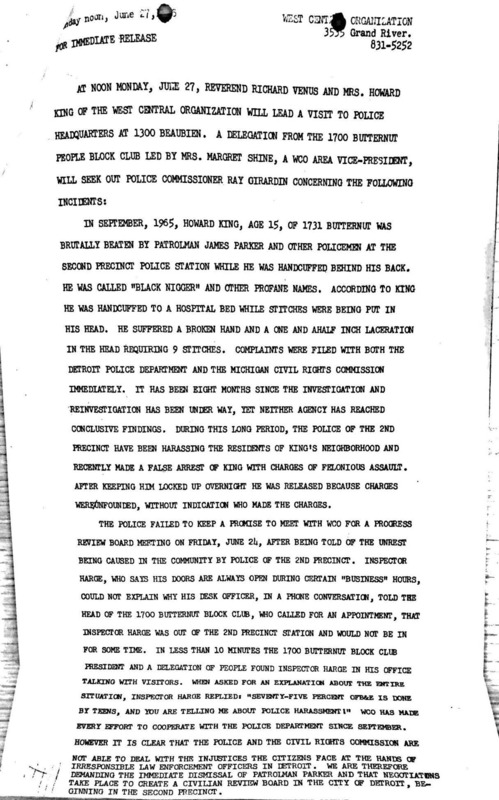

On September 12, 1965, Howard King and three friends, Henry Jackson, Harry Traylor, and Lonnie Stewart, were playing football in the street when two officers arrived claiming the four boys were obstructing traffic. Howard King was beaten by police officer James Parker, receiving a broken hand and requiring nine stitches to a laceration above his left eyebrow. All four boys were arrested and at the precinct station, five or six officers beat and kicked them. The officers also used racist epithets and threatened to shoot the boys if they ever saw them on the street again.

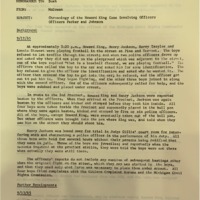

The King family filed a complaint with the DPD and also the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC). The DPD's Citizen Complaint Bureau absolved all of the officers accused of beating the four boys at the station except Patrolman James Parker, because another officer, an African American named Kenneth Johnson, admitted seeing him injure Howard King without cause in the street and then beat the handcuffed teenager in the precinct garage. The CCB recommended that Commissioner Girardin reprimand Parker in some way, but nothing happened.

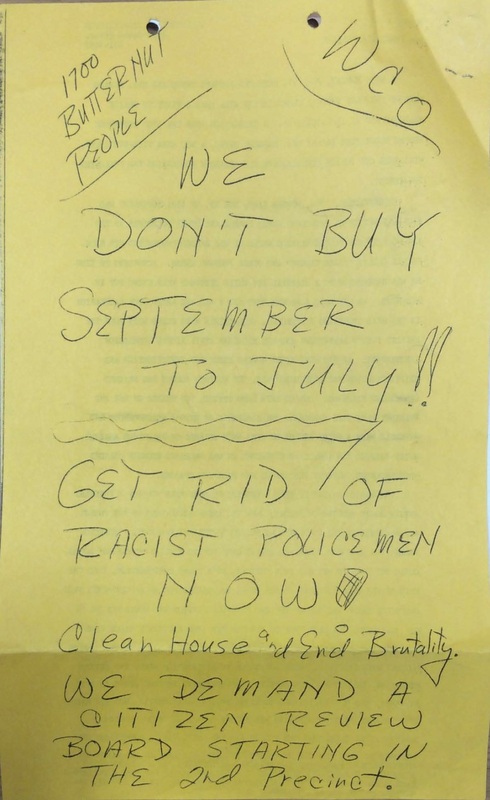

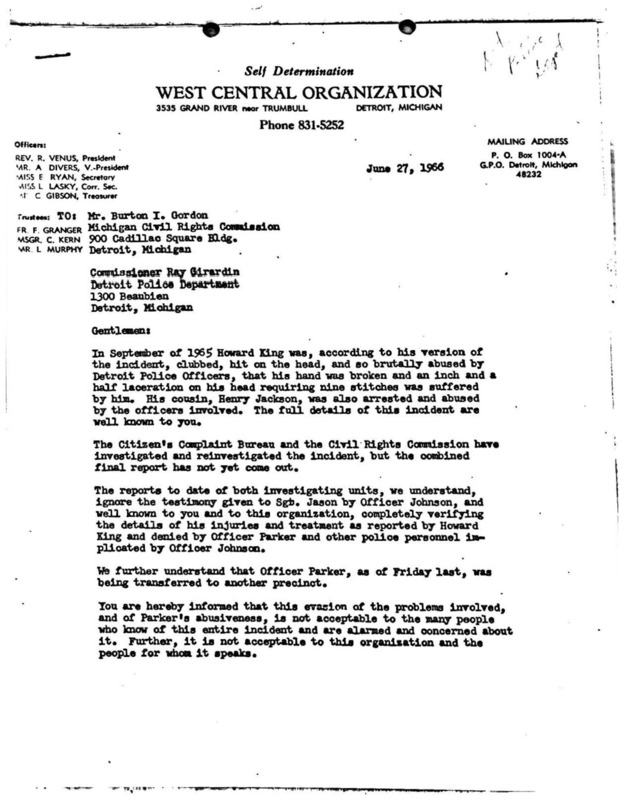

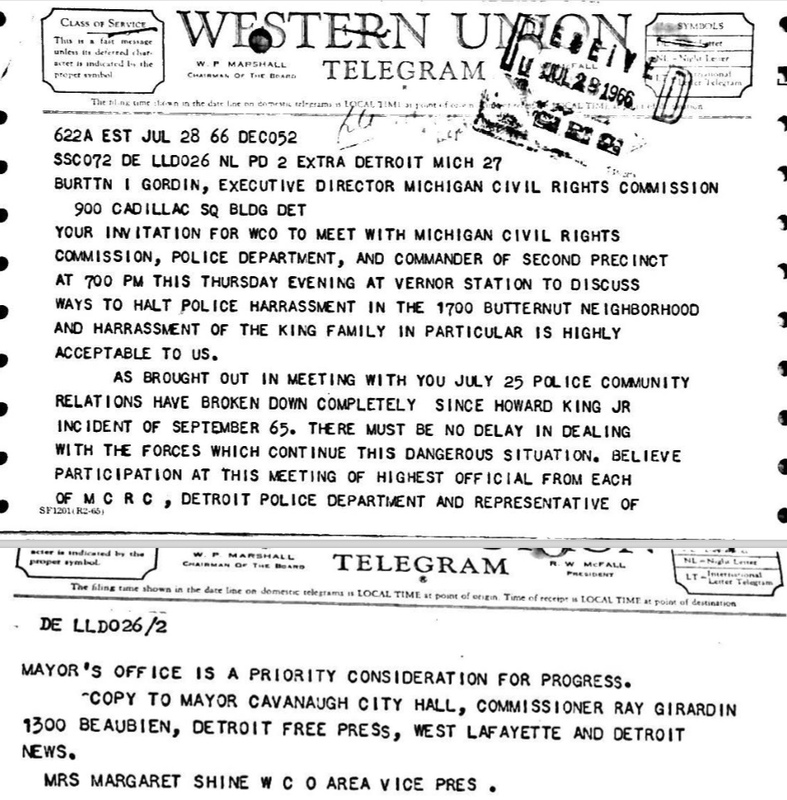

The West Central Organization (WCO), an African American community group, got involved in June 1966 and demanded that Patrolman Parker be brought before a police trial board and then fired. The WCO accused Commissioner Ray Girardin of an "attempted whitewash" and led a protest march on the downtown DPD headquarters (right), demanding the firing of "racist policemen" and a civilian review board. The WCO also protested the recent wrongful arrest of Howard King on assault charges. The police held him overnight with no evidence, and the WCO considered this a clear case of retaliation and intimidation for filing the initial complaint.

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission completed its own investigation and recommended that Patrolman Parker be fired. Instead, Commissioner Girardin agreed to suspend him for six months. The DPD also disciplined Kenneth Johnson, the African American officer who had testified against Parker, which seemed a clear case of retaliation for breaching the "Blue Curtain" of silence. (In 1968, an investigation by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission found that the DPD had illegally punished Johnson and that other officers had enforced the "Blue Curtain" with a sustained campaign of physical and psychological harassment against him).

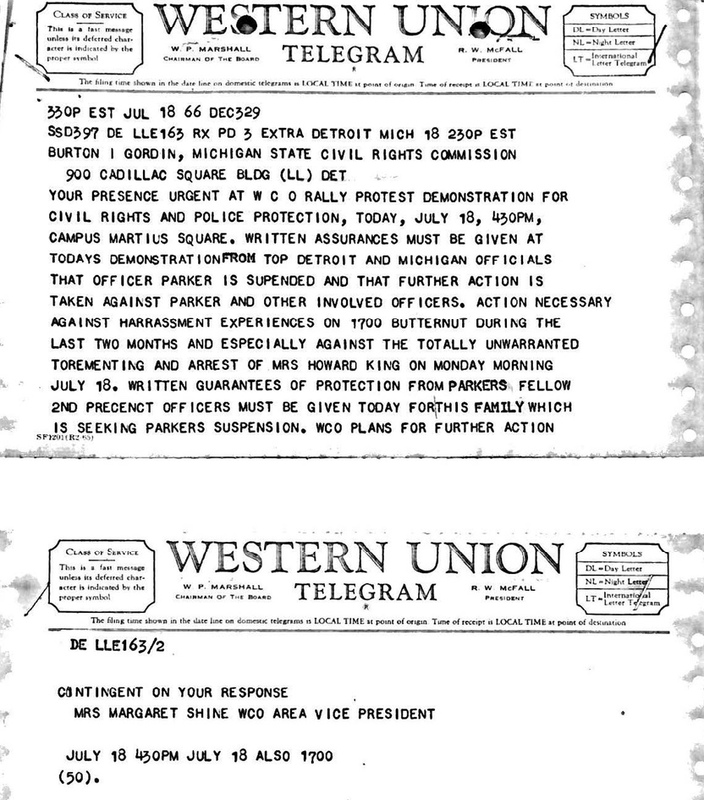

DPD officers stepped up the ongoing harassment campaign against the King family in the summer of 1966, to punish them for pursuing the complaint. Then on July 18, 1966, Howard King was chased and beaten by Patrolman George Patrick after a white boy allegedly told nearby police officers that King had tried to assault him. At the time King was 17 years old. King was walking with his friends Willie and Henry Jackson to a park to play baseball when Danny Reed, a white 18-year-old boy, attempted to hit King with his car. While jumping out of the way to escape the hit, King's baseball bat hit Reed's car. Reed quickly drove away and summoned members of the DPD's Tactical Mobile Unit to arrest King. Patrolman Patrick caught King and beat his neck and ribs with his gun while saying, "You're under arrest, you black SOB."

King escaped from Patrolman Patrick and ran into his home where his mother was. Twelve policemen broke down the door of the King home on 3002 Harrison searching for him. When they did not find him, they listed him as wanted for felonious assault.

Mary Lee King, his mother, stepped outside her home after her son came running in to find out why he was being chased. Police officers beat her, bit her on the neck and dragged her to a scout car. She was assaulted physically and verbally by Patrolman George Patrick. Mrs. King was taken to the Second Precinct and Receiving Hospital to treat the bite on her neck. While there, she was strapped to the bed to prevent her from consulting with her attorney until after the courts closed. She was released at 8:30 p.m. and charged with obstructing a police officer in the performance of his duty, based on a fabricated claim that she had attacked the officer with a 10-inch butcher knife (the prosecutor later dropped this spurious, retaliatory charge of felonious assault).

In response, the West Central Organization held additional protests and demanded an end to the constant harassment of the King family for continuing to pursue their complaint against the police officer. The WCO informed the mayor, DPD, newspapers, and MCCR that "police-community relations have broken down entirely" and that out-of-control police officers had created a "dangerous situation" in the neighborhood. The suspension of one of the officers who brutalized Howard King and his friends in the summer of 1965 was the only tangible result of their efforts, which led to multiple false arrests and beatings for both Howard and his mother Mary, as punishment for their courage in seeking to hold DPD officers who committed felonies against civilians to account.

Read documents from the WCO protest campaign in the gallery below.

Clarence Vester, a 16-year-old African American male, was brutally beaten on his head with blackjacks by Tactical Mobile Unit officers on June 3, 1966 around 2:30 p.m. As a result, Clarence received 10 stitches at Detroit Receiving Hospital. On the same day, his 35-year-old mother, Mrs. Willie May Vester,and 17-year-old brother Eli Vester were also mistreated by the officers present and by the Detroit Police Department.

Clarence was beaten by police after he protested the brutal treatment of his friend Tyrone who had been part of a fight with a neighborhood man. The policemen had knocked down Tyrone's door and dragged him outside to question him about the argument. When Clarence protested their treatment of Tyrone, the officers beat him. Clarence's mother and brother were at home getting ready to go out, when a friend stopped by to tell them there was a fight next door. When they arrived at the scene, the police handcuffed and arrested Eli for telling them to stop beating his younger brother. When Mrs. Vester tried to find out what the charges against her boys were, an officer shoved her so hard that if she had not grabbed onto a nearby post she would have fallen off the porch.

The officers took Clarence and Tyrone to the Youth Home, a juvenile detention center, and arrested Eli and brought him to Vernor Station where he reported being beaten by four policemen in his cell while they shouted, "shut up, black nigger" at him. Mrs. Vester reported to the Michigan Chronicle that “police wouldn’t even let her in to see him at Receiving, apparently because they didn’t want anyone to see how badly he was beaten.” In response, the Afro-American Unity Movement vowed to picket outside DPD headquarters until the police department responded to the charges of brutality brought by the Vester family and other African Americans, especially on the East Side of Detroit.

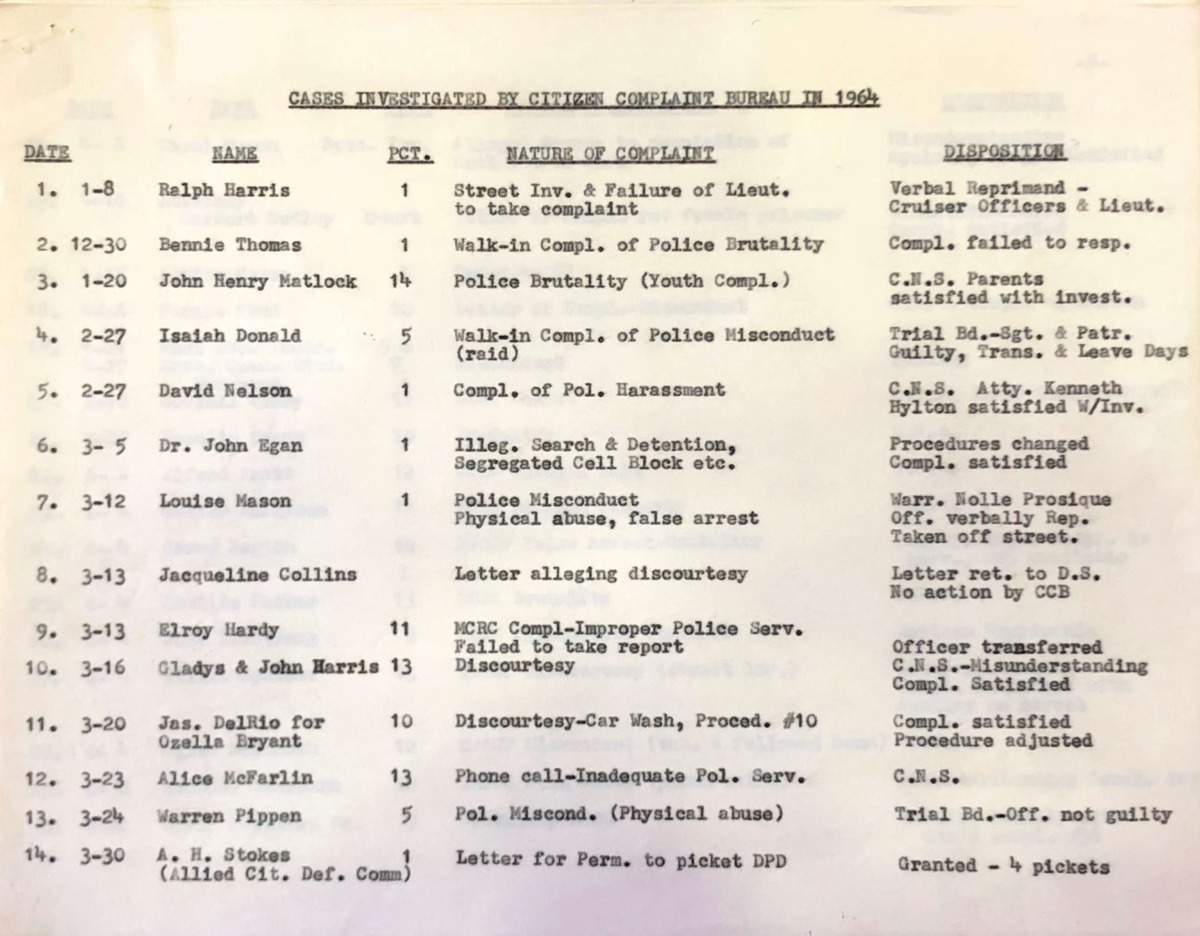

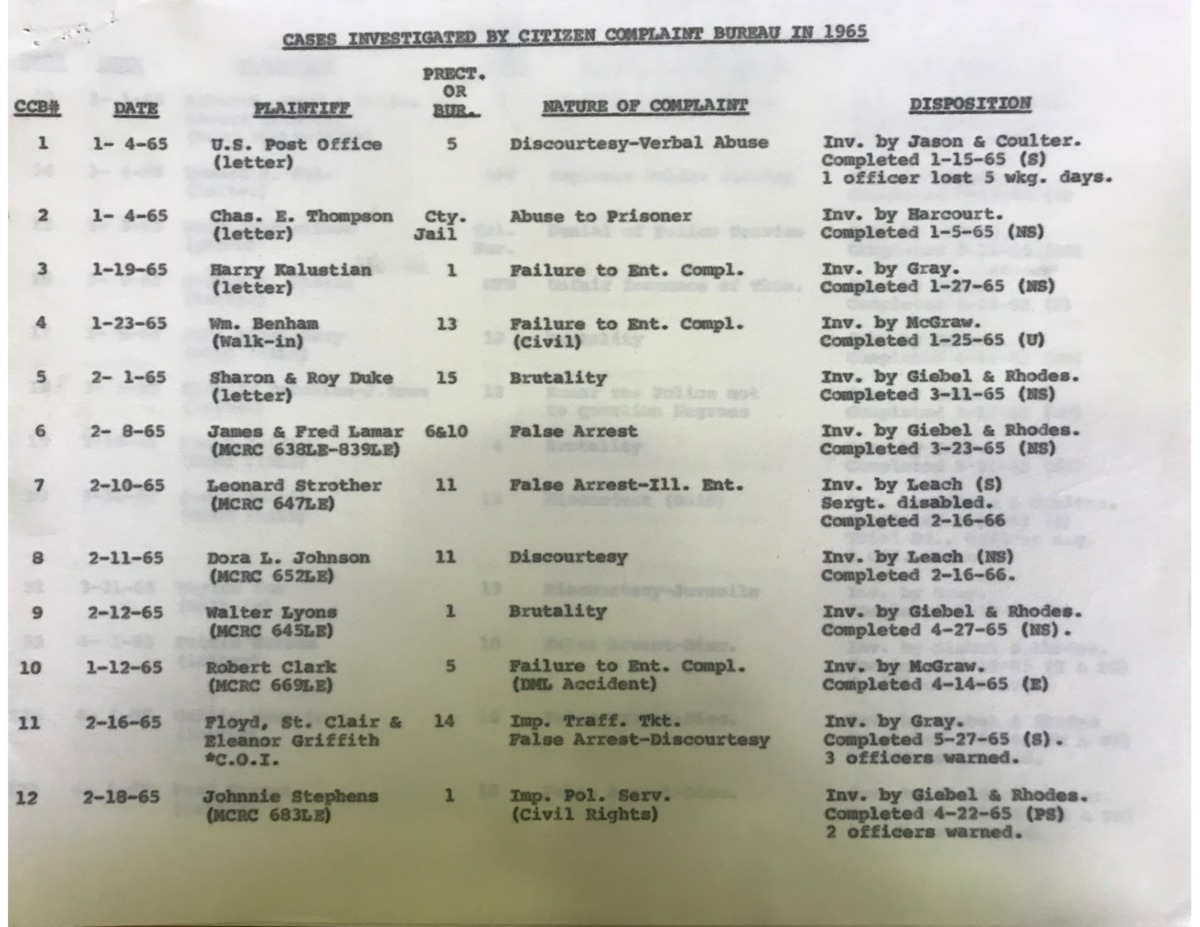

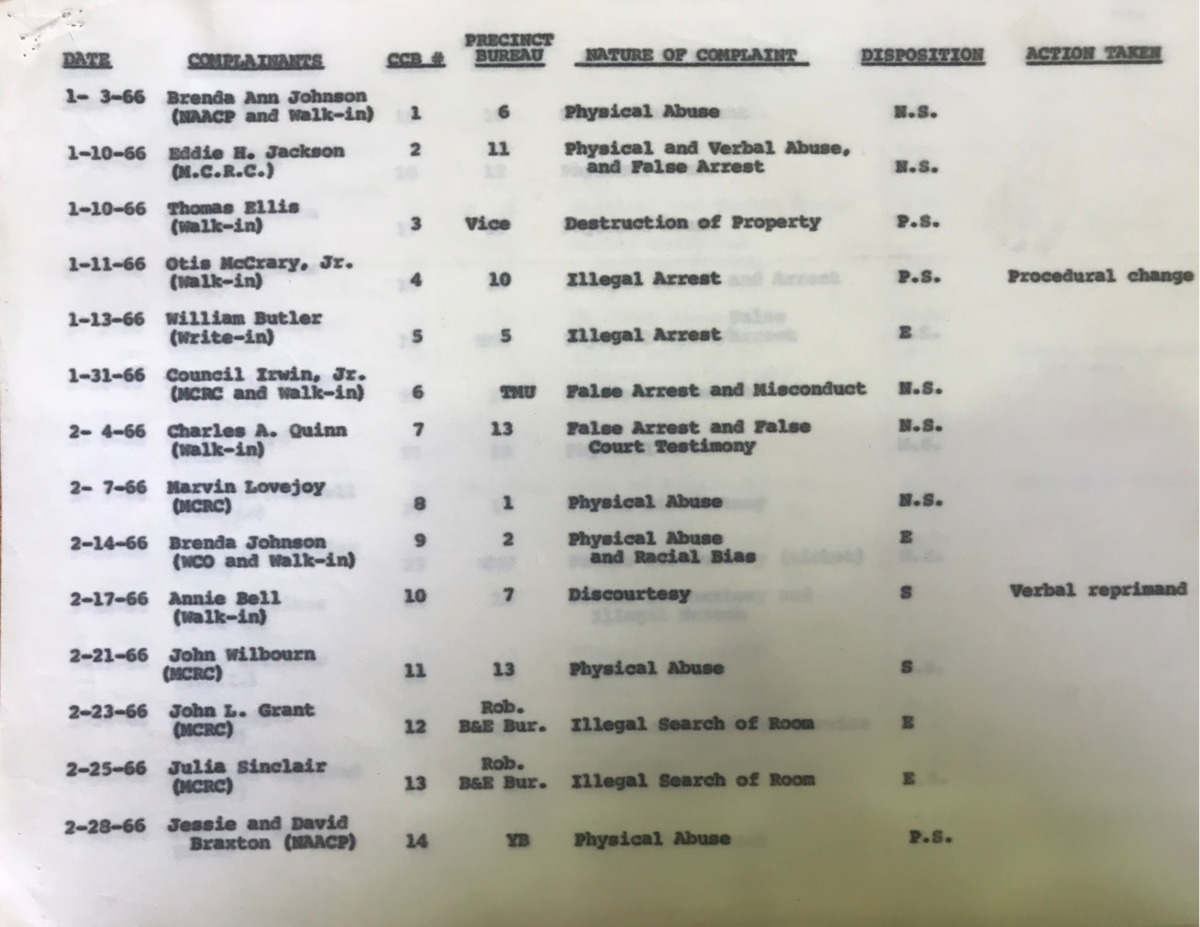

Incidents Reported to Citizen Complaint Bureau at DPD Precinct Level

In the map below, you can click on each labeled precinct to see the number of complaints reported to the Citizen Complaint Bureau between the years 1964 and 1966, also viewable in the gallery below. Most complaints came from the 5th, 7th, 10th, and 13th precincts, which had primary responsibility for the highly segregated African American neighborhoods on the East and West sides. (Note: the map below does not include complaints filed against bureaus that had city wide jurisdiction).

The Citizens Complaint Bureau reported more than 300 cases investigated between 1964 and 1966. Each year, the number of reported complaints increased, which shows that either the incidents of misconduct and brutality became more prevalent, or that black citizens began more frequently reporting incidents due to the revamping of the Citizen Complaint Bureau.

Many complaints received by the CCB came directly from organizations such as the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, the NAACP, and the ACLU. Very few were received directly from the complainant in the form of a walk-in or letter. This is evidence of the mistrust that remained between the African American civilian community and the police department. The DPD also retaliated against civilians who filed brutality complaints, as in the Howard King case above.

A confidential police study found that in police-civilian encounters that resulted in documented injuries during this time period, two-thirds of the injuries to civilians were to the head, and almost half of injuries to police were to the hand, fingers, or knuckles.

The complaints documented here and in the above maps represent only a small fraction of actual incidents of police misconduct and brutality during these years. Because DPD officers often abused and criminally charged black citizens who filed complaints, and because punishment of officers was very rare, it is logical to assume that many African American residents of Detroit were either too afraid or too disillusioned to formally complain.

Systemic, Unpunished Police Brutality

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon, who joined the DPD in 1965 and eventually became chief of police in the 1990s, addressed the issue of police misconduct and brutality in a 2019 interview with our project.

Sources:

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

NAACP Detroit Branch Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Michigan Chronicle

William Serrin, "How Well Does the City Police Its Police?" Detroit Free Press, Jan. 24, 1969 (source of secret police document about injuries)

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon Interview, Part 1, December 3, 2019, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741