Protesting the Cynthia Scott Killing

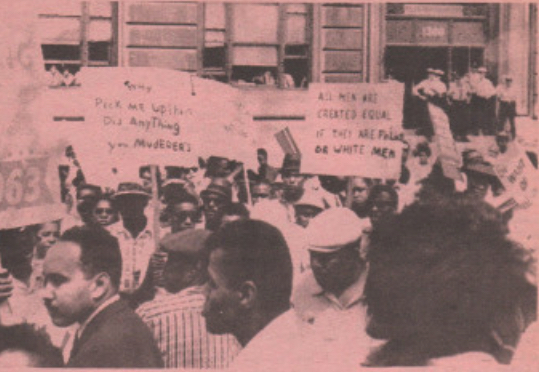

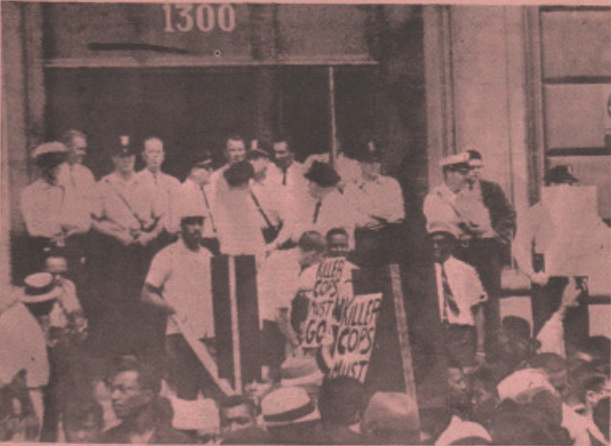

On July 13, 1963, around 2,500 African Americans marched on the downtown headquarters of the Detroit Police Department to demand justice for Cynthia Scott and to protest the Wayne County prosecutor's exoneration of Officer Theodore Spicher, who shot and killed her eight days earlier. Cynthia Scott's funeral took place the same day, with 700 mourners attending the services as St. John's CME Church. The mass demonstration was the first in a series of anti-police brutality marches and protests that represented a militant new phase of Detroit's civil rights movement and signaled a working-class and black nationalist challenge to the middle-class, reformist orientation of the NAACP and the Urban League. Before the event, almost every civil rights group in Detroit sent delegates to a mass meeting to debate the "split among Negro leaders over how militant groups should be in demonstrations against racial discrimination," as the newspapers reported.

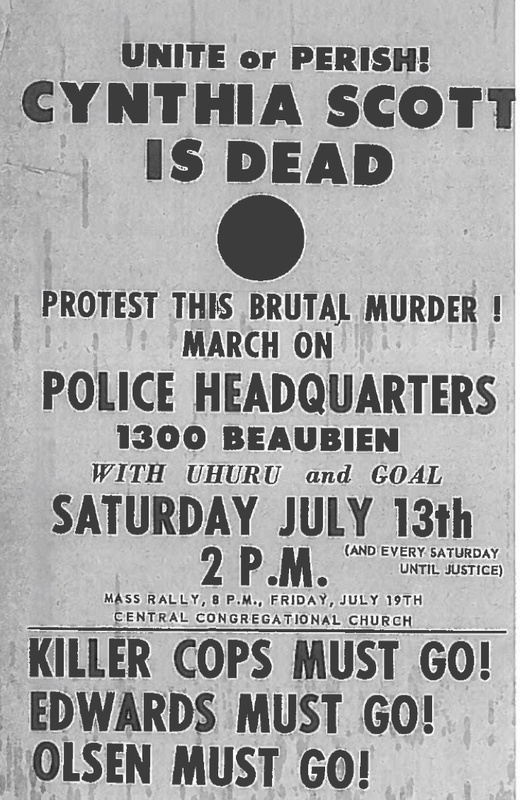

Three recently formed organizations coordinated the July 13 protest: the Group on Advanced Leadership (GOAL), the Detroit Council for Human Rights (DCHR), and UHURU (a Swahili word for 'freedom'). The DCHR, co-led by Rev. Albert Cleage, had been a key organizer of the recent Walk for Freedom and was seeking to supplant the NAACP as the voice of Black Detroit and the representative of 'the masses.' GOAL, formed by Cleage along with the brothers and black nationalists Milton and Richard Henry, also sought to mobilize African Americans in Detroit through a more confrontational approach to police brutality and other forms of racial injustice. UHURU, a black nationalist group clustered around Wayne State, counted among its founders Kenneth Cockrel and General Gordon Baker, who would soon become two of Detroit's most influential left-labor and black power radicals.

Black radicals took center stage among the speakers at the July 13 rally, including Cleage, Richard Henry, UHURU leaders, and Wilfred X, a Nation of Islam leader and the brother of Malcolm X. African American women were not at the microphone but were numerous among the protesters, as the newspaper photographs of the event reveal. The speakers and many protesters demanded a jury trial, rather than a cover-up, to determine Spicher's guilt or innocence under the law. Attorney Milton Henry of GOAL, who obtained a court injunction to prevent the DPD from interfering with the rally, declared that "we don't need the white liberals to lead us in our fight. . . . We must also get rid of our Uncle Toms." Some in the crowd chanted "Cavanagh must go, Olsen must go"--a reference to the liberal white major who had promised police reform, in addition to the county prosecutor who had ruled Cynthia Scott's death a "justifiable homicide." The Michigan Chronicle also commented on the notable number of "prostitutes, pimps, and thieves" who participated in the protest--another indication of the new political dynamic at work in the city of Detroit.

In the days after the march, the leaders of the Detroit Council for Human Rights met with Olsen to demand a reopened investigation, but the prosecutor refused and said that he would not be intimidated into turning the law into a "political" weapon under pressure from a "minority group." Olsen also called the July 13 protest a "vulgar display of power." Mayor Jerome Cavanagh likewise refused GOAL's demand that the city of Detroit reopen its investigation.

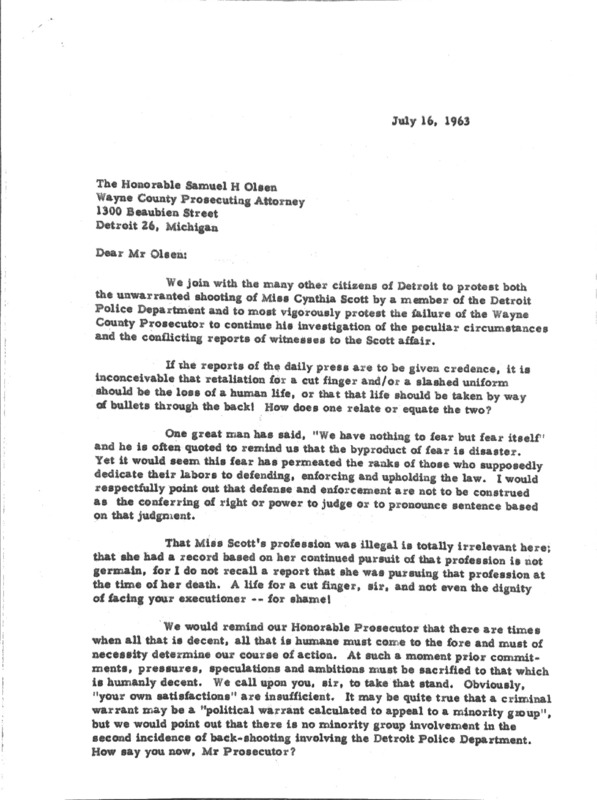

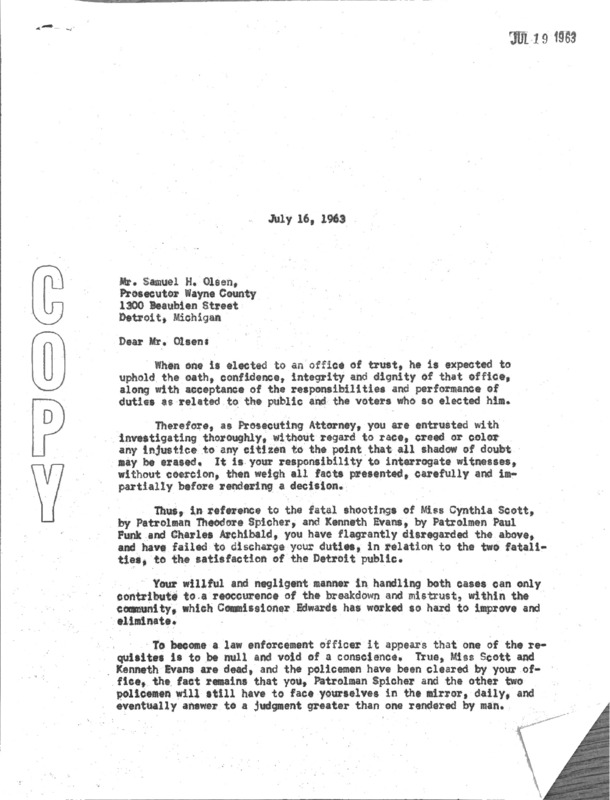

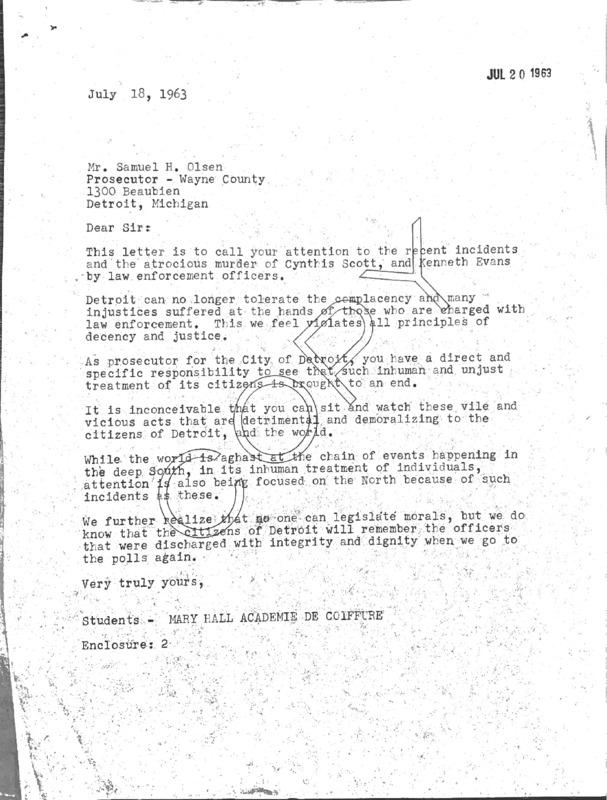

Mainstream civil rights groups, including the NAACP and the ACLU, also called for a new investigation of the shooting and the county prosecutor's determination. The NAACP asked whether "this tragic slaying . . . can be justified by the rule of sound police practice." The ACLU accused Olsen of a "perfunctory investigation" and said the prosecutor "has done immense harm to the cause of lawful law enforcement in this community." The Michigan Chronicle, while commenting that Cynthia Scott was "an immoral woman," also denounced Olsen's "complete white-washing" of an unjustified killing. Thirty black civil rights and civic organizations came together to form Operation Negro Equality and released a statement (right) condemning the prosecutor's "perfunctory investigation and immediate exoneration" of the officers who shot Cynthia Scott and also white teenager Kenneth Evans. The coalition was careful to say that the statement was not a "general indictment of the entire police department."

GOAL and the DCHR took a much more radical stance, pledging to seek the arrest of Officer Spicher through a citizen's warrant and charging, in Richard Henry's words, that the DPD and the county prosecutor had declared "open season . . . against Negro lives and rights." The black nationalists in UHURU also mobilized for the protests (left) and labeled Spicher a "mad dog cop" and the DPD a "low-down vicious anti-Negro machine." The coalition organized a series of additional demonstrations in the weeks that followed, including some in which progressive white activists participated, marking the first sustained direct-action protest campaign against police brutality of the civil rights era in Detroit. Click on the documents in the gallery below to view coverage of this campaign in The Illustrated News, the newsletter of Albert Cleage's church, the Shrine of the Black Madonna.

Charging the DPD with Rampant Illegality

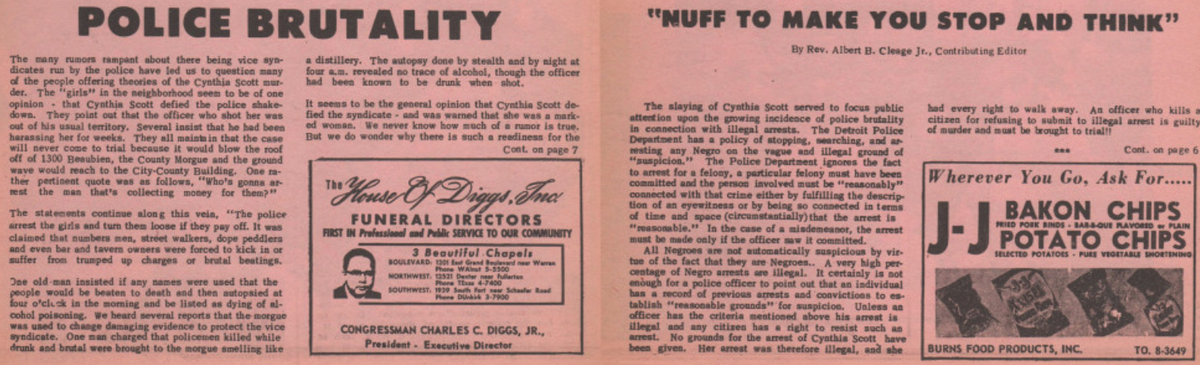

Rev. Albert Cleage's organization argued that the murder of Cynthia Scott represented not only the crime of an individual police officer but also the product of rampant illegality in the procedures and corrupt practices of the Detroit Police Department as an institution. This radical critique of police criminality built on a half-decade of protests by civil rights groups against the DPD's unconstitutional policy of making investigative arrests, but Cleage and his allies also leveled charges about police corruption and explotation of poor and working-class black people involved in vice markets, an issue that was not on the radar of legal-oriented middle-class reform groups such as the NAACP and ACLU.

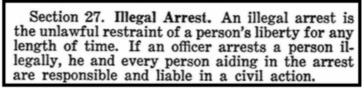

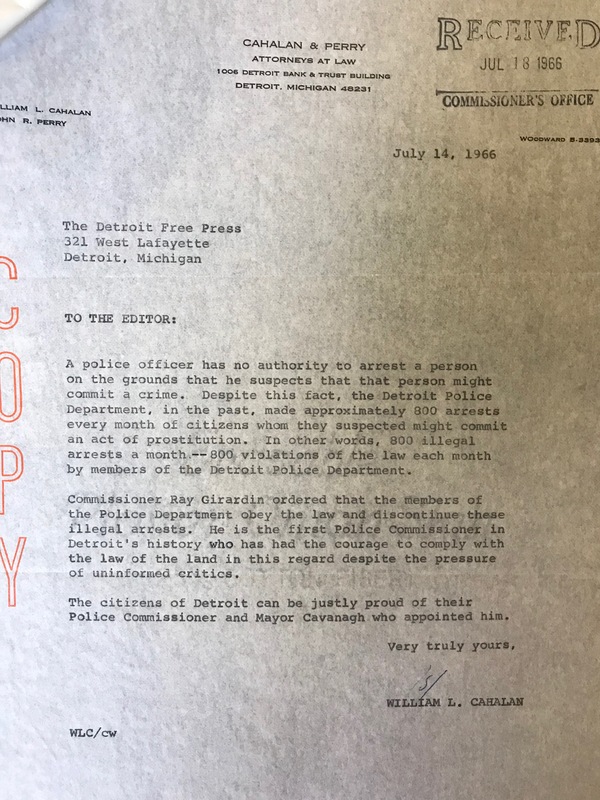

Illegal Investigate Arrests: In a column in The Illustrated News, Cleage argued that the DPD's discretionary policy of basing investigative arrests on mere suspicion without "reasonable" evidence represented a form of mass racial profiling of African American people in Detroit. He charged that a large percentage of arrests of African Americans were illegal, and that "any citizen has the right to resist such an arrest." Officer Spicher, therefore, was "guilty of murder" because Cynthia Scott had every right to refuse to comply with his illegal and arbitrary command.

Note: DPD policy on arrests did not allow an officer to make a misdemeanor arrest without a warrant, unless committed in the officer's presence, and allowed felony arrests without a warrant only if the officer had "probable or reasonable cause" that the person had committed the act (read full policy here). The DPD manual also stated that officers could be held liable in a civil lawsuit for an illegal arrest (right). Cleage's point was that Theodore Spicher had no "reasonable" rationale for believing that Cynthia Scott had committed larceny because he allegedly saw cash in her hand, which meant that the entire sequence of events had proceeded from illegal police action.

The Illustrated News also offered a class-based critique of police violence by expressing sympathy with the concurrent protests taking place in a white working-class neighborhood in Detroit over the fatal shooting of 19-year-old Kenneth Evans by two DPD officers. "We sympathize with the down trodden white folks too," the newsletter declared. "We don't want any street corner capital punishment--white or black." With clear biblical references, The Illustrated News concluded that "the poor, the down trodden, the meek, and the just are in this mess together."

Police Corruption in the Sex Market: The Illustrated News also provided a not implausible motive for why Spicher might have murdered Cynthia Scott that was based on the general sentiment of the women who knew her and also provided sex work in the same area of the city. None of them, of course, had been interviewed by the DPD Homicide Bureau or the Wayne County prosecutor. According to the "girls" who worked the same streets, Cynthia Scott had refused to pay bribes to the police officers who ran the shakedown operation for the "vice syndicates" that controlled prostitution, drug dealing, and numbers running (gambling) in that part of Detroit. They recounted that Spicher had "been harassing her for weeks," and that he was not in his assigned zone of operations on the night he shot her. "It seems to be the general opinion," The Illustrated News concluded, "that Cynthia Scott defied the syndicate--and was warned that she was a marked woman."

This is a very serious, certainly imaginable, but ultimately unproveable charge: that Theodore Spicher shot and killed Cynthia Scott because she did not pay off a police corruption ring, that he and his partner may have been acting on behest of a vice syndicate, and that her murder was intended to send a message to other sex workers in the illicit economy of that area to play ball or suffer the consequences. The Detroit Courier, an African American weekly, also reported a second variation of this rumor, that Theodore Spicher and Cynthia Scott knew each other well and might even have been on intimate terms in the past. Residents of the John R. vice district even speculated that a photograph of the two of them existed, but if any such picture might have been in Cynthia Scott's possessions, a mysterious fire that destroyed her apartment soon after her death would have destroyed it as well. (Spicher filed a $1 million defamation of character lawsuit against the Detroit Courier for this story).

There is no question that police corruption facilitated vice districts in Detroit, including sex workers who serviced a largely white clientele in the John R. district where Cynthia Scott worked and died. In the Michigan Chronicle, an anonymous "John R. Gal" wrote in to report that Cynthia Scott, whom she had known for a year, was "a typical Negro girl trying to get paid for her services from these nasty whites," and furthermore, "most of the cops are tricks also." It was common knowledge that certain areas near Woodward Avenue were 'protected' vice districts, meaning the police did not arrest sex workers who operated inside their boundaries, while others were 'forbidden,' and that this illict economy operated through cash payoffs to dirty cops. According to the Detroit Courier, prostitutes had to pay the police up to $50 per weekend, and/or provide sexual favors, or face a night in jail. And, in the analysis of The Illustrated News, it was in the interest of the entire police department to keep these arrangements quiet rather than investigate what really happened in the Spicher-Scott encounter, because the money flowed upward and a jury trial "would blow the roof off of 1300 Beaubien [DPD headquarters], the County Morgue, and the ground wave would reach to the City-County Building [mayor's and city council's offices].

Read below The Illustrated News's article about the rumors of police corruption (on the left), and Rev. Cleague's column about the DPD's policy of illegal investigative arrests (on the right).

Campaigning for Justice

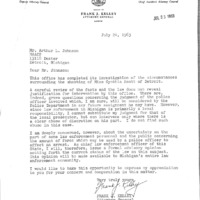

GOAL and the DCHR failed to persuade Detroit's white leaders to reopen the Cynthia Scott investigation, but the protest movement received an initially more favorable response from the office of Michigan attorney general Frank Kelley, who announced that the state government would review Olsen's exoneration of Officer Spicher. But after a brief review, Kelley decided that the state of Michigan would not intervene in the case (left), although he did express "grave questions regarding the judgment of the police officer involved" and implied that the DPD should reassign Spicher to keep him away from street patrols. Kelley also absolved prosecutor Samuel Olsen of any "abuse of discretion." Olsen and the Detroit Police Department claimed total vindication.

The Wolverine Bar Association, a group of African American attorneys, conducted its own investigation and labeled Spicher's actions "totally unwarranted and completely beyond the realm of legality." The Detroit chapter of the National Lawyer's Guild, a left-wing organization, accused the Wayne County prosecutor of the "crudest perversion of law and fact the committee has ever encountered" and charged Olsen with a prejudical and unethical "desire to obtain exoneration from the very outset." The anger among Detroit's African American groups also renewed calls for a civilian review board to hold the police department and prosecutor accountable.

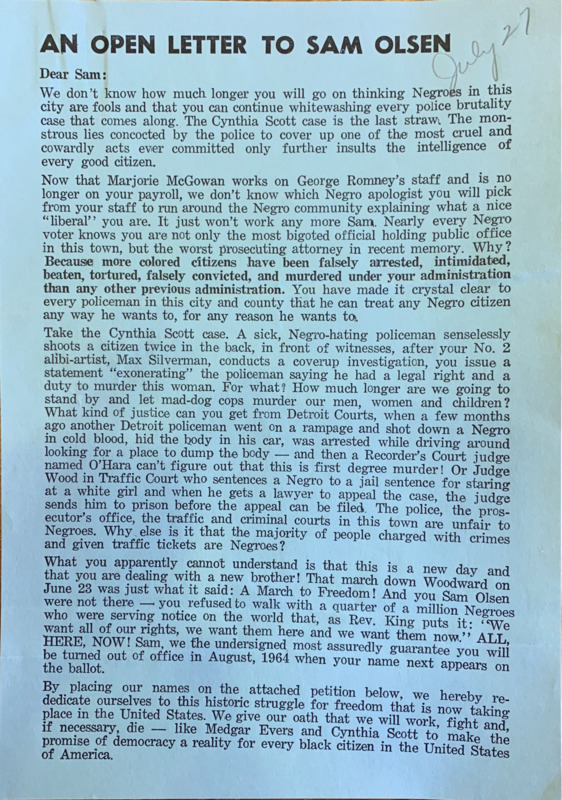

African Americans in Detroit also launched a petition drive to recall Samuel Olsen as prosecutor. Their "Open Letter to Sam Olsen" (below left) accused the prosecutor of "whitewashing every police brutality case that comes along" in one of the "most cruel and cowardly acts every committed." The denunciation was fierce:

The Open Letter labeled Theodore Spicher a "sick, Negro-hating policeman" and said that the black community was no longer going to allow "mad-dog cops murder our men, women, and children." The gallery below contains the Open Letter and three other letters from citizens to Samuel Olsen charging him with a cover-up of murder.

Lillian Scott's Lawsuit

Lillian Scott, Cynthia's mother, filed a $5 million civil lawsuit in late July against the city of Detroit and Theodore Spicher after her attorney, Milton Henry of GOAL, failed to secure a citizen's warrant for Spicher's arrest. The civil proceedings began as GOAL continued its weekly pickets of DPD headquarters. Milton Henry, Lillian Scott's attorney, tape-recorded the deposition provided by Officer Spicher and then told the media it had revealed "conclusive evidence that the killing was a plain case of murder." Lillian Smith sat six feet away from her daughter's killer throughout the deposition.

In mid-August, the Cavanagh administration introduced a city ordinance to indemnify city employees from personal liability for actions "arising out of the good faith performance of their official duties," including bodily injury and death. From then on, the city of Detroit assumed liability for, and therefore almost always defended in court, the actions of police officers accused of misconduct, brutality, and wrongful death.

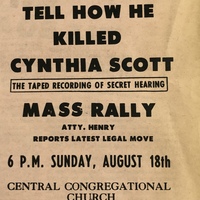

On August 18, GOAL called a mass rally (left) to escalate the protest campaign and invited Detroiters to come hear the tape of Theodore Spicher describing the homicide. Seven hundred people attended the rally at the Central Congregational Church, where Rev. Albert Cleage announced a mass voter registration drive with the goal of removing Prosecutor Samuel Olsen from office. The audience, however, did not hear the audio recording. At the Cavanagh administration's urgent request, Wayne County Circuit Judge Edward Piggins issued a last-minute order demanding that GOAL surrender not only the tape but also any transcripts of Spicher's deposition. GOAL leader Richard Henry pledged to defy the court order, but unidentified DPD officers threatened to storm the event and make mass arrests if the organizers played Spicher's words to the crowd, and in the end GOAL did not take the risk.

It is clear that the city's white elected officials and the white leaders of the criminal justice system feared that the tape recording would incite violence, even though all of the GOAL/DCHR protests had been peaceful thus far. In his ruling, Judge Piggins warned that playing the tape in public would be a "menace and an obstacle to good race relations" and accused GOAL of "an effort to exploit this court for the purpose of inciting and distortion of the minds of decent citizens."

Lillian Scott did not win her civil lawsuit against Theodore Spicher and the City of Detroit for the wrongful death of her daughter Cynthia. GOAL responded by filing a conspiracy lawsuit in federal court against Judge Piggins and Police Commissioner George Edwards, for his actions below, which also was unsuccessful.

Burying the Truth

In late July, Police Commissioner George Edwards returned from a three-week European trip and announced that he would review the evidence in the fatal shooting of Cynthia Scott and also of the white teenager Kenneth Evans. But even before his review, Edwards publicly stated that the Spicher-Scott encounter had started with her commission of a dangerous felony, "a knife assault on a police officer," revealing that he did not plan to reassess the contrary eyewitness testimony and instead would only evaluate whether Spicher's decision to fire was legally justified. GOAL immediately denounced Edwards for refusing to acknowledge either that Spicher initiated the confrontation by attempting an illegal arrest or that the DPD's pattern of illegal arrests represented "a crime in itself."

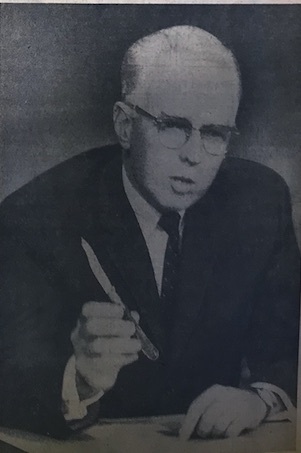

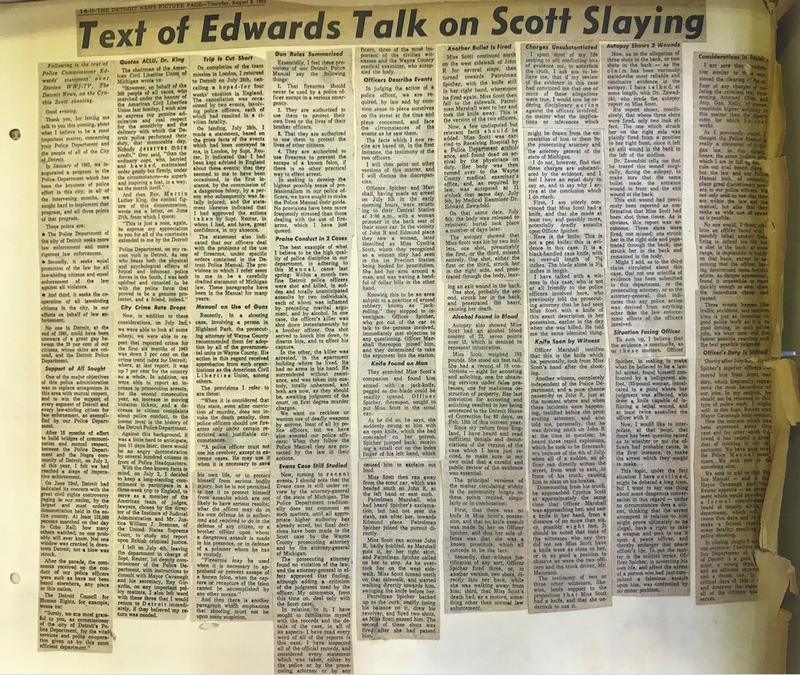

Commissioner Edwards, a prominent white liberal and noted police reformer, delivered the results of his review in a televised address on August 7, 1963. He began by acknowledging the serious tensions between the DPD and black citizens when he became police commissioner and credited his reforms that sought "equal protection of the law for all law-abiding citizens and equal enforcement of the law against all violators." He then read the police manual's policy on use of firearms to the audience, emphasizing the right of an officer to shoot in self-defense and to "prevent the escape of a known felon." Edwards informed Detroiters that he had personally re-interviewed both police officers, Theodore Spicher and Robert Marshall, along with three civilian witnesses and the medical examiner. (He chose not to re-interview the African American witnesses who had had recounted seeing Spicher and Marshall frame Cynthia Scott after her death).

Edwards retold the story, first and foremost, from the viewpoint of Theodore Spicher, with added narrative dramatization designed to criminalize the victim.

- Cynthia Scott, a known prostitute, was "waving a handful of dollar bills" in her hand when the officers stopped to investigate.

- When Spicher tried to put her in the squad car, she "suddenly swung at him with an open knife," wounding him.

- Cynthia Scott then "ran away," but when Spicher caught up to her, she "started walking directly toward him, swinging the knife before her."

- Spicher fired twice.

- She turned back toward Spicher--meaning she continued to initiate the confrontation--and he fired again.

- Then Officer Marshall took her knife away.

- Edwards also emphasized that Cynthia Scott was very inebriated, that she was six feet tall and weighed 193 pounds, and that she had been convicted ten times of prostitution-related offenses.

Only then, and far more briefly, Edwards addressed and refuted the versions "circulating widely in the community" that Cynthia Scott had not attacked Spicher with a knife, that he fired into her back while she posed no threat, and that the motive was--euphemistically--"something other than normal law enforcement."

- The commissioner held up the knife and emphasized its deadliness ("the blade alone is 3.25 inches in length").

- Then Edwards highlighted the most dubious of all the eyewitness accounts, the lone white civilian testimony--by a man who allegedly jumped out of his truck at 3:05 a.m., on his drive back to the suburbs from a known vice district that serviced a white clientele, to run over and get a close look at an active crime scene, right after a police officer had just shot a person, and conveniently saw a woman dying on the ground with an open knife in her hand.

- Edwards also highlighted testimony of other witnesses that Cynthia Scott carried a knife, which was not illegal and would not be unexpected for a sex worker on the night shift.

- He then discounted the multiple witnesses who swore that she never pulled a knife on the police officer--the multiple African American witnesses--as not being as reliable as the white man who jumped into the middle of the scene.

- He also never mentioned the African American eyewitness testimony that the officers had either planted a knife on Cynthia Scott, or removed her own knife from her purse and placed it in her hand, and then cut themselves in the safest way possible after she was motionless face down on the ground.

- Instead, Edwards was "utterly convinced" that Cynthia Scott made multiple "deadly assaults" on Theodore Spicher.

Edwards therefore exonerated Officer Spicher for using deadly force to defend his life and prevent a dangerous felon's escape, and he further stated that "not one scintilla of evidence" had been provided that Spicher's actions in instigating the encounter were based on anything except routine police work. Cynthia Scott, he reiterated, was a "belligerent six-foot, 193-pound woman" who "committed a felonious assault." Edwards also warned that the rhetoric from protest leaders, that a civilian had the right to "take a weapon and seek to use it" on a police officer during a potentially illegal arrest, was "dangerous." (This charge was a severe distortion, is not outright slander, of Rev. Cleage's argument that Cynthia Scott had "every right to walk away," because GOAL leaders consistently argued that she never attacked Spicher with a weapon).

In closing, and in a modest concession to the anger in Black Detroit, Edwards announced that the DPD would create an internal Board of Inquiry that would investigate and report to the commissioner (not the public) on every police shooting that resulted in a fatality. He also implied that an officer with better reactions might not have found it necessary to shoot Cynthia Scott in the back and recommended that Officer Spicher be reassigned to desk duty.

The gallery below includes the full text of Commissioner Edwards's address, diametrically opposed responses from a white and a black newspaper, and the DPD's belated concession in 1966 that its longtime de facto policy of investigative arrests was illegal.

"A Flimsy Whitewash"

The fact that two of Michigan's most well-respected white liberal Democrats, DPD Commissioner George Edwards and Attorney General Frank Kelley, found it necessary to criticize Officer Spicher's discretionary use of deadly force, even while exonerating him based on their purported acceptance of his story about Cynthia Scott's aggressive and violent behavior, means that one or both of two conclusions about law enforcement and racial power in a northern city circa 1963 are true. Faced with irreconcilable accounts between a police officer potentially prosecutable for first-degree murder, and multiple African American witnesses who swore that he shot and killed an unarmed person without cause, Edwards and Kelley chose to believe the two white men who had clear incentives to lie, and the one white witness whose account was highly dubious on its face, rather than the six African American residents of Detroit whose witness accounts were broadly consistent as well as damning to both Spicher and his partner Robert Marshall. Commissioner Edwards and Attorney General Kelley either swallowed their doubts in order to protect the power of police to control Black Detroit and avoid setting a precedent in charging a white officer for murdering a black woman, or they believed the three white men rather than the six black witnesses because both white liberals remained steeped in and representative of a political culture of white supremacy and black criminalization. Most likely, some combination of both interpretations is true.

The black power groups that had led the recent protests roundly condemned Edwards's exoneration of Officer Spicher and denigration of Cynthia Scott. GOAL's Richard Henry labeled the address a "flimsy whitewash" and pointed out that the police commissioner had dwelled on Scott's criminal record but not mentioned prior charges of police brutality against Spicher. GOAL also promised more demonstrations and proposed the disarming of all police officers on the street. The grassroots anti-police brutality coalition--GOAL, DCHR, and UHURU--demanded the appointment of an African American as the next police commissioner, which Mayor Cavanagh termed "ridiculous." GOAL and other African American organizations, including the Wolverine Bar Association, also lobbied President John F. Kennedy, unsuccessfully, to withdraw Edwards's pending nomination for a federal judgeship.

The mainstream civil rights and civil liberties organizations also strongly questioned the outcome. The ACLU expressed appreciation for the commissioner's program to improve police-community relations but reiterated its call for a review panel of disinterested citizens to investigate charges of police misconduct. The NAACP also criticized the Edwards decision and stated that, in effect, police officers had free reign to commit murder by claiming after the fact that the victim had resisted arrest, because the DPD and prosecutor were always willing to classify such alleged resistance as a felony. Rev. James Wadsworth, the NAACP president, also insisted that Cynthia Scott had been unarmed and shot in the back "unnecessarily and with malice aforethought," followed by a coverup based on "the well-known phantom knife" that guilty officers knew would result in their exoneration.

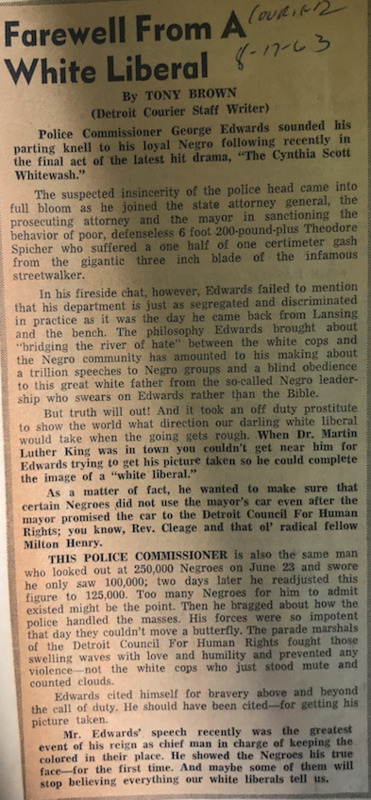

African American newspapers offered mixed reviews. The Detroit Courier, in a column about "The Cynthia Scott Whitewash," argued that despite his liberal rhetoric of color-blind law enforcement, Edwards was leaving the DPD for the federal judgeship without having made any major changes to the racial segregation and rampant discrimination on the police force. "It took an off duty prostitute," the Courier concluded, to expose Edwards as the real face of white liberalism, "in charge of keeping the colored in their place." The Michigan Chronicle, the more moderate of the two African American weeklies, expressed disagreement with Edwards's decision but praised his overall record of standing up to white racists inside the DPD and seeking to improve police relations with the black neighborhoods of the city.

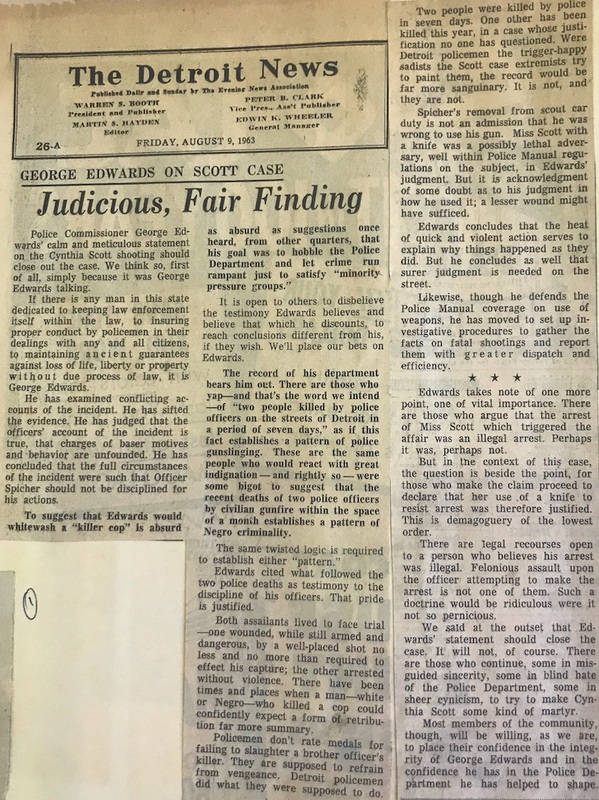

The white newspapers and other city officials closed ranks. Mayor Cavanagh had said very little publicly during the crisis but let it be known that he supported Edward's position. The city council had been considering launching its own investigation but dropped the idea after the mayor's counsel advised that it lacked the authority, and after Edwards's address sent a message that the matter was closed for white liberal Detroit. The Detroit Free Press praised Edwards's impartiality and criticized civil rights radicals for seeking to "exploit" the situation. The Detroit News (above, second from left) also lauded the commissioner and condemned "those who," meaning African American activists who, "try to make Cynthia Scott some kind of martyr, . . . some in misguided sincerity, some in blind hate of the Police Department."

A Brief Epilogue about State Violence and White Supremacy

During July and August of 1963, while African Americans demanded justice for Cynthia Scott, the white DPD officers who worked the John R. vice district entertained themselves in verse, according to a now retired policeman. Before roll call at the 1st precinct, one officer who played guitar would lead a song that began: "Run, Cynthia, run/Spicher gone to get his gun."

Sources

Box 117, Folder 2, George C. Edwards, Jr., Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

--note: the above collection includes a scrapbook with dozens of undated newspaper articles from July/August 1963 from the Detroit Free Press, Detroit News, Michigan Chronicle, Detroit Courier, utilized for this page

DPD Homicide Bureau, "Fatal Shooting of Cynthia Scott Broady," July 10, 1963, DPD Cynthia Scott File A20-02255 (FOIA file)

NAACP Detroit Branch Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

The Illustrated News, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Corporation Counsel documents on removing civil liability from city employees, Box 80, Folder 30, Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit (2007)

David Maraniss, Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story (2015)

"Police and the Black Community," Michigan Chronicle, Feb. 24, 1973