3. Liberal "Get-Tough" Policies

In 1961, Detroit rejected Mayor Louis Miriani’s conservative “get-tough” approach to policing by electing Jerome Cavanagh as the city's new mayor; in 1965, Mayor Cavanagh would win re-election because of his own liberal “get-tough” approach to policing.

The two mayors cracked down on crime during different eras for different reasons, but both expanded the power of the Detroit Police Department (DPD) through "get-tough" policies. Under Mayor Miriani, the Detroit Police Department (DPD) routinely used physical force and intimidation against civilians, causing particularly deep mistrust and fear in the African American community. The “Crash” program of 1961—during which the DPD racially profiled and illegally arrested more than 1,000 African American men—best exemplifies “get-tough” policing under Miriani. Cavanagh’s opposition to the Crash program won him the trust of civil rights organizations that believed he would end such practices and implement their suggestions for reforming the DPD.

In the mid-1960s, as police warned of a crime wave, civil rights activism in Detroit intensified, and fear of an urban riot grew, Cavanagh’s liberal administration implemented a series of “get-tough” policies. Because of the stigma attached to the phrase “get-tough,” Cavanagh distanced himself from the term, although members of his administration including Police Commissioner Ray Girardin used it when speaking to the press. Cavanagh's policies were designed to deter crime and empower officers on the street—linked to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s national War on Crime.

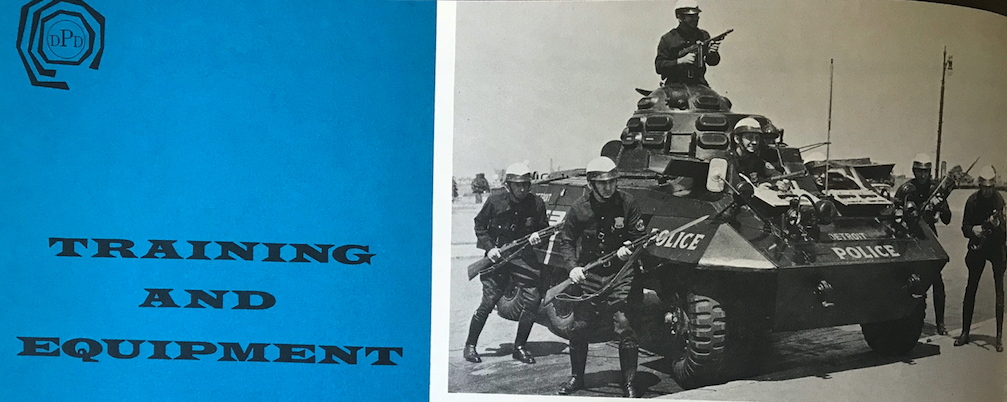

Mayor Cavanagh and his police commissioner, Ray Girardin, promised to enforce "law and order," a phrase that invoked police crackdowns against political demonstrators as well as law-breakers. In a 1965 report to the public, Girardin defined this mission as "preserving the public peace and order, apprehending offenders, protecting the rights of persons and property. The DPD boasted of its new militarized technology, including a tank (above), and its highly professionalized police force, thanks to better pay and more rigorous qualifications. The headline of the DPD report, reproduced in full at the bottom of this page, was "Law and Order . . . Backbone of Civilization."

The four pages within this section describe how the Cavanagh administration "got tough" on crime during an era of civil rights activism: implementing policies that gave officers discretionary authority, including a controversial "stop and frisk" law; creating the militarized Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU) to subdue crowds, from potential 'riotors' to civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protesters; and illegally surveilling progressive and radical organizations using the Red Squad.

The 1965 Mayoral Election

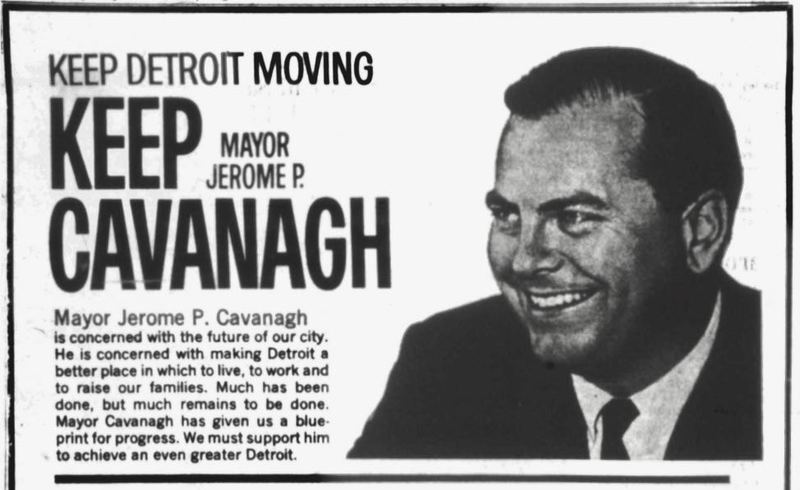

In 1961, Mayor Cavanagh's platform earned him the overwhelming support of liberal white and black Detroiters as well as the support of many in the white working class. Cavanagh believed that Miriani's police force could be reformed by offering human relations seminars, improving officers' working conditions, and recruiting a more diverse class of cadets. With these changes, liberals believed justice would become color-blind. In 1965, the interracial electoral coalition that Cavanagh had assembled remained strong when he faced the Republican candidate for mayor, businessman Walter Shamie.

While Shamie defined himself as a moderate Republican, he secured the approval of conservative white voters by supporting the successful "homeowners' rights" movement to overturn Detroit’s fair housing ordinance, which would have made racial discrimination in the sale and rental of property legal (the courts overturned the result.. In the months leading up to election day, Shamie questioned Cavanagh's approach to law enforcement and tried to make crime a central campaign issue. Crime rates were allegedly on the rise (although crime data is inherently unreliable): a report released in August 1965 revealed that Detroit’s crime rate had risen 15.1% in one year. Shamie criticized Cavanagh’s efforts to reform the DPD, telling the Detroit Free Press that instead of “meddling” in the police department’s internal affairs, “we need more police and we need to restore authority to the police, . . . by appointing a commissioner who can win confidence.”

Cavanagh rejected these charges and campaigned on his record of police modernization and professionalization, including new technology and better pay to improve the quality of the force (document at right). Despite Shamie’s efforts to undermine voters' confidence in Cavanagh's administration, the mayor’s coalition kept faith in his promises to deter crime and ensure “fair, firm and equal law enforcement.” As a result, on November 2, 1965, Cavanagh won re-election by a two-to-one margin.

1965 marked an important transition for Mayor Jerome Cavanagh. The mayor ran on a promise to further the goals of the civil rights movement, establish lasting equality for Detroit's citizens, and promote integrity and professionalism among the Detroit police force. In 1965, these campaign pledges came under question, as the mayor supported and created numerous initiatives that prioritized "firm"police enforcement and jeopardized the equality of Detroit citizens. Anti-knife and anti-loitering ordinances were among the most blatant shifts in policy. These ordinances expanded police discretionary oversight and strengthened the DPD's ability to detain citizens on the street who did not commit a criminal offense. Additionally, at the advice of Commissioner Girardin, Cavanagh promoted and enacted a new branch of police officers: the Tactical Mobile Unit. The TMU's goals were to quickly and efficiently handle emergency situations that likely involved massive crowds. Though this agenda of "riot control" was the official duty, the TMU proved to be an extension of militaized policing into minority communities and actively participated in police harassment and brutality of black residents. Finally, Cavanagh rigorously supported the enactment of a statewide stop and frisk law, allowing police to stop, search, question, and even detain 'suspicious' individuals who were innocent of criminal offenses. Together, these initiatives marked a major shift in the treatment of crime in Detroit by its mayor and police department: punitive "get-tough" measures embraced by liberal politicians who simultaneously expressed support for the civil rights movement's agenda.

Sources:

Detroit Free Press

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Alex Elkins, "Liberals and 'Get-Tough' Policing in Postwar Detroit" in Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies (Wayne State University Press, 2017)

Alex Elkins, "The Origins of Stop-and-Frisk," Jacobin Magazine (May 9, 2015), https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/05/stop-and-frisk-dragnet-ferguson-baltimore/

Gloria Brown Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Michigan Chronicle

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library