2. The Creation of STRESS

Stop The Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets (STRESS) was a specialized police tactical unit introduced by DPD Commissioner John Nichols and approved by Mayor Roman Gribbs in January 1971. As envisioned, the STRESS unit teams would deploy undercover for surveillance and decoy operations and therefore deter street crime by catching and arresting muggers and robbers in the act, or even in anticipation of the crime that they were presumably about to commit. Police officers volunteered to join STRESS, which was overwhelmingly white and quickly gained a reputation within the DPD as an elite strike force and a prestigious assignment for the toughest cops. The unit targeted black "street criminals" almost exclusively, and its operations quite obviously, indeed unapologetically, revolved around racial profiling as its very foundation for existence. As STRESS co-commander James Bannon told Newsweek after the first anti-STRESS protests in the fall of 1971:

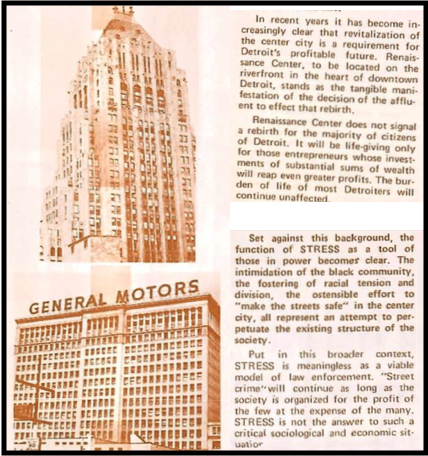

DPD leaders justified this targeted and militarized focus on certain alleged criminals in specific "high-crime" areas with the explanation that STRESS sought to protect the law-abiding African Americans in Detroit who were the primary victims of muggings and other street crimes. Based on the geographic areas where STRESS primarily deployed, this explanation was partial at best and did not acknowledge the primary mission: to crack down on black street crime, and criminalize black youth in public spaces more generally, in order to protect white-owned businesses in the downtown and midtown commercial districts during an era of massive white flight to the suburbs and extreme fear among white leaders and residents of Detroit that African Americans would soon become a majority and take political control of the city and its police department.

The existence of STRESS remained hidden from the public until Commissioner Nichols revealed the operation in April 1971. The protests against STRESS began five months later, in September, after an undercover officer shot and killed two unarmed black teenagers, and massive demonstrations by African American groups continued sporadically for the next two years. STRESS officers had already fatally shot seven other young African American males before this pivotal September incident and ultimately killed 12 civilians during 1971 and at least 19 people total before the unit's disbandment at the end of 1973. Four police officers also died from gunfire during STRESS operations, including a county sheriff's deputy shot and killed by STRESS officers in a controversial and murky incident. The violence precipitated by STRESS, and more broadly by its "proactive policing" philosophy, played a central role in the Detroit Police Department's killing of more civilians per capita during the early 1970s than any other large urban department in the United States.

"Proactive Policing" as Racial Profiling

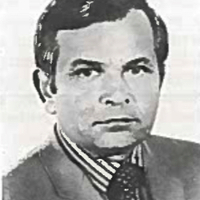

The intellectual architect and co-commander of STRESS was Detective Inspector James Bannon, who had a reputation within the DPD as an expert on police administration and an advocate of police professionalization. In the fall of 1970, Commissioner Nichols asked Bannon and other members of his command staff to devise new methods to reverse the rise in muggings after the release of data showing that about 80 percent of robberies that year had been crimes against persons on the streets, and that--at least according to the DPD's justification of STRESS--85 civilians had been killed during the commission of these crimes. In an article championing STRESS methods for The Police Chief (gallery, below left), Bannon and Nichols called robbery "the most vicious of crimes," whether in the form of armed assault or the snatching of a purse, because of the physical and mental trauma suffered by victims who experienced "abject vulnerability" and became afraid to be outside on the city's streets. In the article, they also explained the analysis of crime data to create a profile of high-crime areas that would be targeted; a portrait of the typical crime victim, middle-aged and 75% African American; and the common perpetrator: "young, 17 to 29, and nonwhite." The architects of STRESS portrayed this explicit racial profiling operation as a well-intentioned deterrence program based on neutral crime statistics that sought most of all to protect black residents of inner-city neighborhoods who lacked the resources to move to the suburbs and also faced racial prejudice and housing discrimination when they attempted to escape urban dangers.

Bannon's team, including STRESS co-commander Inspector Gordon Smith, decided that "ordinary police methods would not suffice." They devised the concept of "zero visibility patrol," where undercover teams of male officers would deploy on foot in order to attract street criminals by disguising themselves as drunks, derelicts, elderly people, prostitutes ("in drag"), or vulnerable "ladies" with wigs and purses. Support units, also in plainclothes and similar costumes, would be stationed nearby in unmarked patrol cars and other disguised ways such as riding bicycles or posing as repairmen. The STRESS officers (who were more than 90% white) would blend in as "citizens of the neighborhoods in which they worked." Although never officially acknowledged, this meant STRESS focused mostly on the so-called crime corridors in the racially mixed commercial districts, rather than in the heart of Detroit's segregated black neighborhoods (where white officers disguised in these ways would have been conspicuous nonetheless). "The nature of the mission," a DPD analysis of STRESS explained, "was to operate in plain clothes in such a way as to 'merge' with the environment, and to appear to be the type of person a thug seeking a victim would be likely to confront."

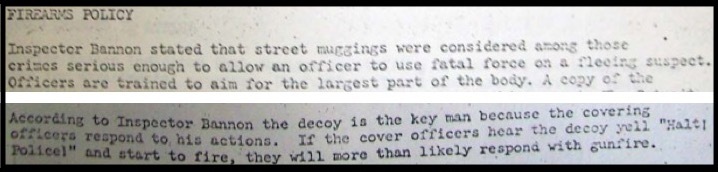

Bannon and Nichols portrayed the decoy operations as an effective deterrent that would confront street criminals with three choices: not break the law, surrender when the police ambushed them, or be shot and likely killed. As the body count rose, the DPD hierarchy justified this shoot-first philosophy by characterizing the targeted black teenagers and young adults as "thugs," "felons," and "muggers" who knew the rules of the game and had made the choices that sealed their fate. The STRESS team utilized federal funding from the 1968 Safe Streets Act to create the unit's communications infrastructure, train decoy officers on permissible use of deadly force (justified under DPD policy and state law to "prevent a felon's escape"), and show them how to avoid entrapment techniques (critics soon charged that the entire operation was illegal entrapment at its core). Bannon estimated that about 80% of the STRESS operations involved general surveillance of high-crime areas and 20% of the deployments placed decoys directly on the street as bait to draw out the criminal element. The decoy method was particularly deadly, accounting for 9 of the first 10 fatal shootings by STRESS during 1971, but only 59 of the unit's first 1,747 arrests--an extraordinary 15% fatality rate in police decoy encounters with alleged criminals.

It is clear that the architects of STRESS expected, and (as quoted above) indeed predicted, the flurry of fatalities. It was also highly misleading for Bannon and Nichols to claim repeatedly in various public forums that most of the teenagers and young black men killed by STRESS were armed with guns and extremely dangerous--most were not, as detailed later in this section. Many were unarmed and shot in the back as they fled, often unaware the men shooting at them were even police officers. In several cases they were attacked and gunned down without provocation by STRESS officers just because they were young black males in criminalized parts of the city targeted by an aggressive and militarized racial profiling operation designed to deter Detroit's "criminal element" through overwhelming and deadly force.

Inspector James Bannon later boasted that STRESS was based on a new "proactive policing" concept: "We came up with the idea of invisible, zero visibility, policemen who would be present to interdict crime." He championed the militarized approach for empowering highly trained police officers on the street--"a combination CIA and Green Beret group with badges"--to operate with almost total discretion in designing their own independent investigations of dangerous criminals. Bannon did acknowledge that this form of aggressive, preemptive policing "has perhaps been unacceptable to Americans." In the Police Chief article, intended to encourage other police departments to follow Detroit's lead, Bannon and Nichols stated that they had expected deadly violence to result from "the encounters with holdup men, who found that instead of a helpless victim they had actually selected a brave and highly competent police officer." Matter of factly, and with language that obscured the controversial circumstances of many of these incidents, they reported that "eight felons were slain by STRESS officers" in the first eight months of the operation. Bannon and Nichols portrayed these deaths as the responsibility of the robbers--the "felons" and "thugs"--and emphasized consistently that STRESS was a welcome innovation for the African American residents of Detroit, who "recognize that they are the chief residents of black crime, and they want something done about it."

Read more about the origins and methods of STRESS in the gallery below, featuring the DPD perspective, a 1971 investigation by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission that relied on information provided by Inspector Bannon, and the opening section on STRESS's "bloody beginnings" in an expose by the radical group From the Ground Up, which was organized by some of the same white New Left activists who formed the Ad-Hoc Action Group in 1968 to protest police brutality.

What Was the Real STRESS Mission?

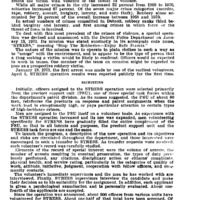

There is strong evidence that the DPD's stated rationale that STRESS was designed primarily to protect black crime victims in black neighborhoods was false, or at least fundamentally misleading. The geographic location of STRESS deployments, although a closely held DPD secret, clearly targeted the racially mixed commercial districts in and near the downtown and midtown centers of business, shopping, professional sports, and other recreational activities (see map at right; interactive version here). These included nearby areas notorious for so-called vice markets, especially the underground economy of prostitution and narcotics, that had long operated with the corruption and complicity of police officers. Most of the STRESS decoy shootings clustered in these central city commercial districts as well, indicating that the unit was actually targeting the less common but media-hyped problem of black-on-white street crime in interracial zones of commerce, rather than the much more frequent occurence of black-on-black crime in racially segregated and economically disadvantaged neighborhoods that the DPD itself claimed to be the motivation. The other two clusters of undercover decoy shootings also happened in business corridors along the racial dividing line between Black and white neighborhoods on the northeast and far east sides of the city.

The clearest evidence that the DPD's defense of STRESS was based on false pretenses was barely hidden in plain sight. It is striking and otherwise inexplicable, in a decoy and surveillance program purportedly designed to protect the disproportionately black victims of street crime in Detroit, that more than 90% of the undercover STRESS officers patrolling neighborhoods in disguise and posing as vulnerable crime victims were white. In its first year of operation, STRESS was almost exclusively white, and even after community protests and widespread demands to integrate the unit, only 9 of the more than 100 active STRESS officers were African American as late as the spring of 1973. If concern about black crime victims had really been the rationale for STRESS, as Inspector Bannon and Commissioner Nichols often claimed, then the DPD would have recruited black police officers to pose as the majority of undercover decoys and deployed them primarily in other parts of the city. Instead, the design and deployment of the decoy and surveillance teams sought to catch black perpetrators who targeted white victims, which was the main fear of white residents of the city and suburbs when they ventured into the downtown business corridor.

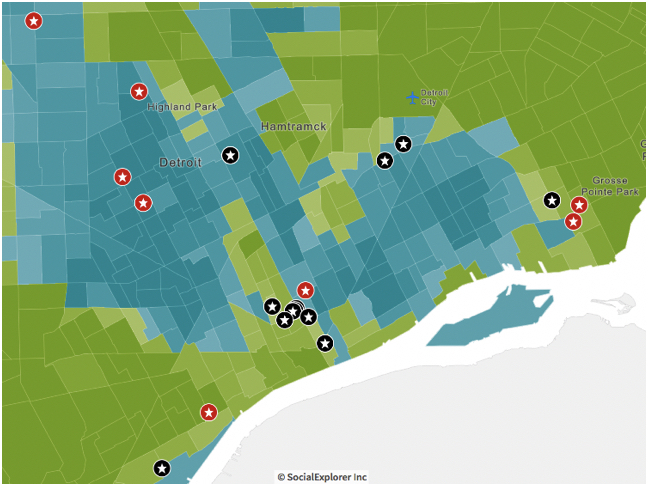

This led radical groups such as From the Ground Up, an ad hoc coalition that produced the "Detroit Under STRESS" expose in 1973, to charge that the unit actually operated to protect the interests of downtown-based corporations that depended on white shoppers, sports fans, and other suburban commuters who were extremely fearful of black street crime and highly responsive to media hype about alleged crime waves and epidemics. From the Ground Up observed (at right) that the geographic deployment of STRESS teams seemed clearly designed to "make the streets safe" in the central business districts, by sending a public relations message to white residents of metropolitan Detroit that the police department was cracking down on black youth, by violently pacifying sections of the city that had existing white capital investments or were undergoing gentrification and redevelopment. The expose pointed out that street crimes were in reality 'crimes of poverty' and desperation, but that STRESS was not mobilized to protect other "high crime areas" in poor and segregated black neighborhoods, or to address the "police complicity in the drug traffic" that exacerbated rather than lessened the dangers for the residents of the city. From the Ground Up's report also challenged the DPD's constant claims that a large majority of black residents of Detroit supported STRESS and instead cited a survey--albeit one conducted in 1973 after the unit's fatality rate generated an enormous backlash--that 78% of the city's white residents approved of STRESS while 65% of the black population expressed opposition (gallery, above right).

The "Detroit Under STRESS" investigation placed the unit's origins within the long history of white racial control and DPD oppression of the black citizens of Detroit, from the police department's commitment to defending segregated white neighborhoods since the 1920s, to the violent and deadly law enforcement suppression of black citizens in the 1943 race riot and the 1967 "rebellion." From the Ground Up recounted the DPD's consistent refusal to investigate or discipline its officers for brutality and even murder, including in the cold-blooded killings of three black teenagers in the Algiers Motel Incident, and concluded that "into this atmosphere of police misconduct and brutality, STRESS was born." Despite the DPD's claims that its policies screened out officers with disciplinary records, STRESS included policemen such as Raymond Peterson, who had injured at least 21 civilians before joining the unit and whose team was involved in 8 fatal shootings. From the Ground Up challenged the DPD's claim that STRESS had reduced street crime and concluded that its real purpose was "to terrorize and intimidate the black community" through the complete militarization of police operations:

Creating Crime

The STRESS-based philosophy of "proactive policing" was not actually brand new. Such methods had a much longer history in the form of stop-and-frisk tactics and other forms of preemptive and discretionary racial criminalization, in addition to longstanding law enforcement polices of illegal surveillance of political activists under the guise of preventing violence. It is more accurate to view STRESS as a particularly and deliberately deadly version of the strategy of preemptive policing that was sweeping the nation in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the wars on crime and drugs, often conducted through militarized tactical units as well as undercover operatives, and based on the theory that low-level criminals such as street dealers and teenage muggers must be incarcerated or incapacitated before their threat escalated into a full-blown urban crisis. As Commissioner Nichols and Inspector Bannon claimed in the "Zero Visibility Policing" article, "the parameters of robbery often include rape and even murder" and even low-level muggings and purse snatchings created an urban environment of "violence and bloodshed." Although statistically and sociologically flawed, this gateway theory that petty crime and general disorder would escalate into total mayhem justified police methods of mass racial profiling, the comprehensive racial criminalization of young black males in public space, extraordinary state violence, and rampant police criminality.

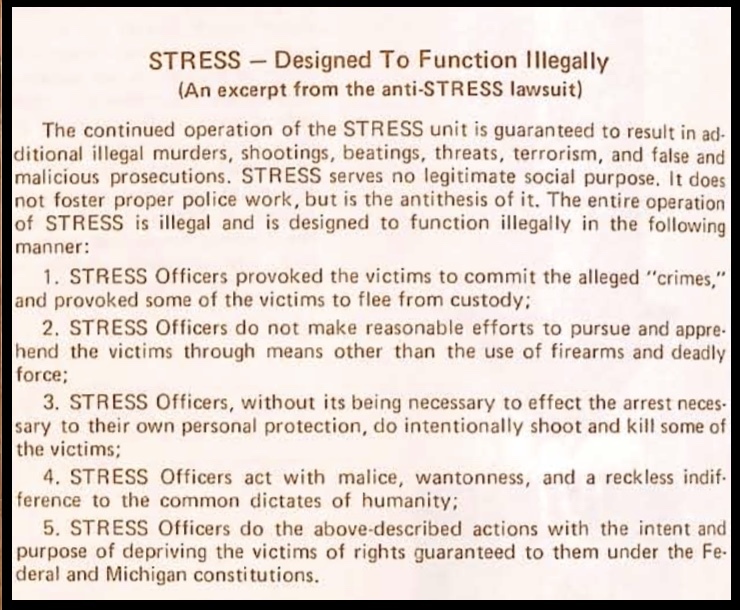

As implemented in the streets, by undercover STRESS officers given total discretion to draw out African American 'criminals' and then gun them down, the preemptive policing program actually created crime and exacerbated urban violence in multiple ways. The STRESS methods imposed criminality and then escalated police violence on young black males who were not just caught in the act of a robbery but were merely present ("loitering") in a 'known crime' area, or holding a "suspicious" object, or acting in "suspicious" ways, or who understandably responded to an ambush by armed men whom they often did not even realize were undercover officers by running for their lives. STRESS also created crime by facilitating and preemptively justifying police criminality in a department that flatly denied that its officers ever committed brutality or used excessive force against civilians. First black radicals, and then mainstream civil rights groups, came to view STRESS as a state-sponsored terror campaign by white officers who murdered juvenile delinquents and petty thieves and plainly innocent black people, by undercover operatives who could not be identified by their victims and by other witnesses, by policemen who were always protected by the DPD's whitewashed internal investigative process and by the consistent justification of deadly force by the Wayne County prosecutor. "The entire operation of STRESS is illegal," a team of radical lawyers charged in a class-action lawsuit filed in 1972, because undercover officers through both formal DPD policy and their discretionary methods on the street "provoked the victims to commit the alleged 'crimes.'"

Sources:

John F. Nichols and James D. Bannon, "S.T.R.E.S.S.: Zero Visibility Policing," The Police Chief, June 1972

“Street Crime in America: The Police Response,” April 12, 1973, Hearings before the Select Committee on Crime, House of Representatives (Washington: GPO, 1973)

From the Ground Up, "Detroit Under STRESS," 1973, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Allen Phillips, "STRESS: A Concept as well as a Unit," Detroit News, March 21, 1973

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)