Ad-Hoc Action Group

"The level of police violence in the city was unbelievable. I was outraged and I felt that I had to take a stand"--Sheila Murphy, who founded the Ad Hoc Action Group-Citizens of Detroit in May 1968 after Cobo I

In early June 1968, the Ad-Hoc Action Group staged a multi-day sit-in at Mayor Jerome Cavanagh's office to protest the police brutality against marchers in the Poor People's Campaign at Cobo Hall on May 13. The protest was biracial (right), but almost all members of the Ad-Hoc Action Group were white. They described themselves as "concerned white people" who supported the "Black Community" and wanted to demonstrate that not all white Detroiters endorsed the racism and violence of the police department. The Ad-Hoc Action Group demanded punishment for the police officers involved in the Cobo I assault as well as broader DPD reforms: a civilian review board to investigate police brutality, appointment of an African American police commissioner, African American commanders in majority-black precincts, hiring of black police officers to match the population ratio, and enforcement of the residency requirement for all DPD members (below right).

Sheila Murphy, a white student at Wayne State University, was 21 years old when she founded the Ad-Hoc Action Group-Citizens of Detroit. She grew up near downtown Detroit steeped in the radical social justice tradition of the Catholic Worker Movement, of which her parents were leaders. In 1966, she joined the West Central Organization, a militant black empowerment and community control organization based on the Saul Alinsky model of grassroots organizing. The Ad-Hoc Action Group, which usually went by the shorter version of its name, operated out of the headquarters of the West Central Organization and acted as a liaison of sorts between black power activists in Detroit and white leftists and more liberal Catholic social justice adherents, a number of whom lived in the suburbs. The Ad-Hoc Action Group defined its mission as a police watchdog ("cop-watching") organization and, within a year, had around 250 active members and another 750 or so supporters. Among other activities, the Ad-Hoc Action group regularly held meetings in suburban locations and brought African American activists from Detroit to tell those gathered what policing was really like in the inner city. Many of the supporters were middle-class professionals who believed that an organized political movement led by college-educated white youth and Catholic priests would be more influential in convincing the city government to force the DPD to reform. Sheila Murphy's direct-action political style was more confrontational, but she also initially believed that the Ad-Hoc Action Group would be able to work within the political system to bring about necessary change under the liberal Cavanagh administration. They would soon find out otherwise.

The white activists in the Ad Hoc Action Group were both politically radical and racially privileged, as Sheila Murphy recognized and acknowledged. Within a year, she received multiple awards and significant media attention for her contributions to the civic good, which is obviously not something that tended to happen to black power activists, or even young black women who spoke out against police brutality and often suffered direct physical retaliation instead. Most white police officers appeared to despise her, even naming their Police Athletic League mascot "Sheila the Pig." In the police union's newsletter, DPOA leader Carl Parsell singled Murphy out in denouncing "self-annointed leaders and religious fanatics, carrying the flag of police brutality." The DPD's Intelligence Bureau illegally spied on the Ad-Hoc Action Group, and soon after its formation, the headquarters of the West Central Organization was "mysteriously ransacked," almost certainly by police operatives. This harassment indicated the Ad-Hoc Action Group's increasing prominence and effectiveness in bringing media and public attention to the crisis of police brutality between 1968 and 1970.

Protesting Cobo I and Cobo II

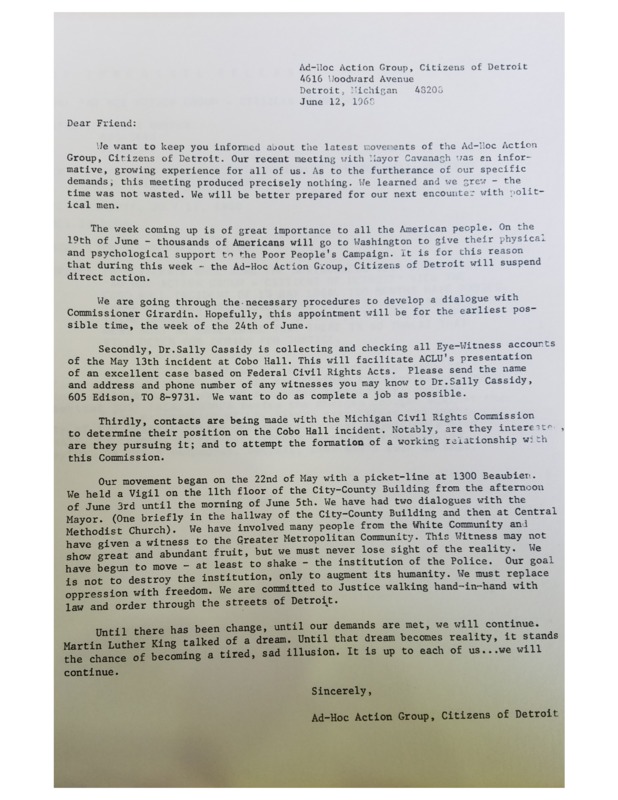

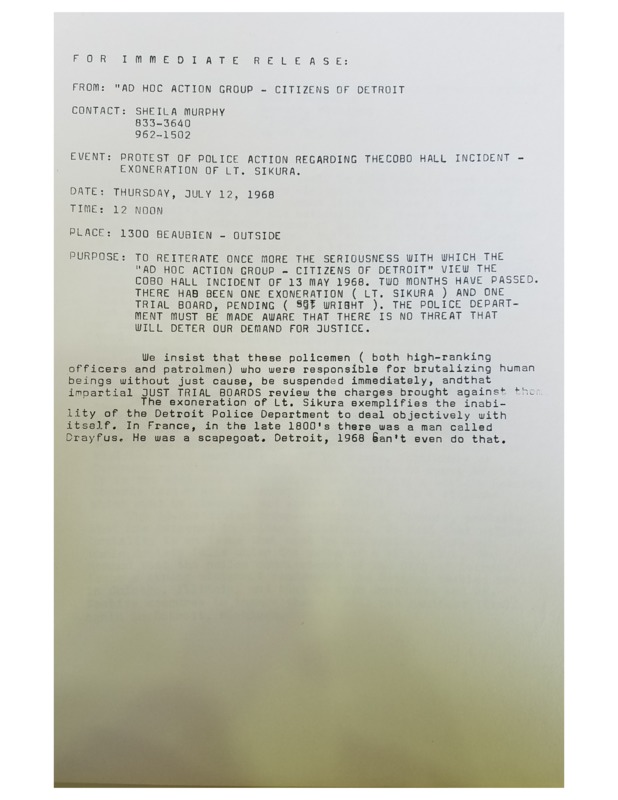

Sheila Murphy and other members of the Ad-Hoc Action Group held their first public protest against the police attack on the Poor People's Campaign on May 22, nine days after the incident. They picketed the DPD's downtown headquarters at 1300 Beaubien and issued their six demands for police reform (above right). Next the Ad-Hoc Action Group held a three-day vigil and sit-in ouside the mayor's office, from the afternoon of June 3 to the morning of June 5, when Jerome Cavanagh agreed to meet with them. Youthful activists and Catholic priests were prominent in this vigil, and their language was religiously oriented in the tradition of the social gospel and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Ad-Hoc Action Group declared that the members of the white community must bear "witness" to metropolitan Detroit about the racial injustices faced by African Americans in the city and called for "law and order-BASED ON JUSTICE."

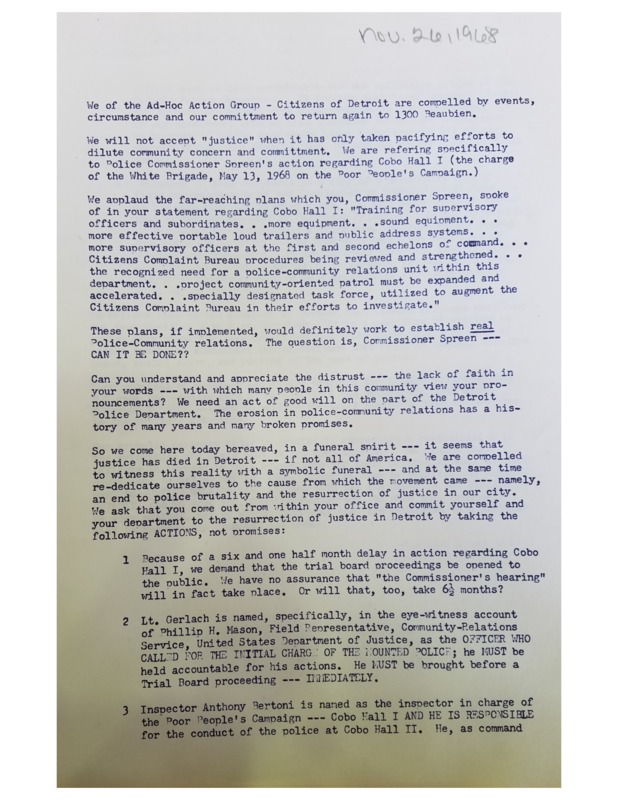

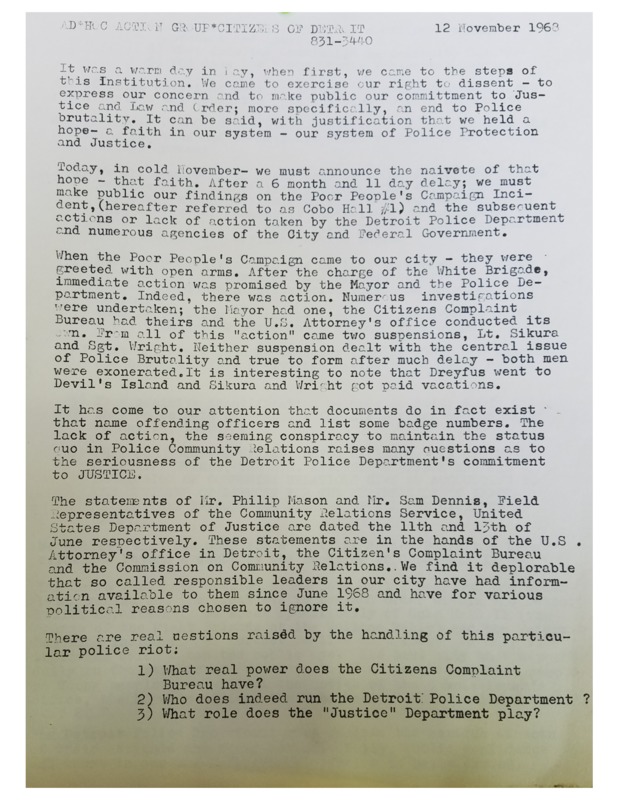

Mayor Cavanagh promised the Ad-Hoc Action Group that the DPD would conduct a thorough and unbiased internal investigation of the Cobo I incident, which was the opposite of what happened. In mid-July, Sheila Murphy organized a second protest at DPD headquarters after the police trial board exonerated and praised the ranking officer on the scene. As the Citizen Complaint Bureau investigation dragged on, the Ad-Hoc Action group organized a third picket line outside DPD headquarters in November. These protesters, including four Catholic priests and a number of young activists, brought an open casket with a blue curtain to symbolize the DPD's code of silence and protection of guily officers. The accompanying manifesto strongly denounced DPD Commissioner Johannes Spreen, as well as the DPOA union, and demanded "an end to police brutality and the resurrection of justice in our city." In its own investigative report, the Ad-Hoc Action Group labeled Cobo I a police riot after reviewing the evidence submitted by the U.S. Department of Justice observers and the Detroit Commission on Community Relations witnesses.

The refusal of the DPD and the Cavanagh administration to conduct an impartial investigation further radicalized the leaders of the Ad-Hoc Action Group. In announcing its Cobo I investigation findings, the Ad-Hoc Action Group argued that DPD policies had caused the violence against the Poor People's Campaign and that punishment should not be limited to low-ranking patrolmen, as scapegoats. The Ad-Hoc Action Group also pledged to work with African American organizations to establish civilian control over the DPD through a city charter amendment, a campaign that unfolded in 1969 as detailed below. Sheila Murphy publicly charged that the Citizens Complaint Bureau was "castrated," under the effective control of the DPOA union and a DPD hierarchy that stonewalled all inquiries into police brutality and misconduct. The Ad-Hoc Action Group also supported the unsuccessful civil lawsuit filed by radical attorneys against the DPD after the Cobo I violence.

Read about the Ad-Hoc Action Group's initial protest campaign after Cobo I in the gallery below.

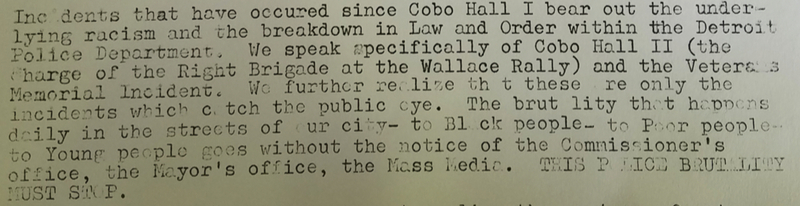

The Ad-Hoc Action Group escalated its protests in the fall of 1968 after the police assault on anti-Wallace protesters outside Cobo Hall and the drunken off-duty police violence against African African youth at the Veterans Memorial dance happened in rapid succession. Its November 1968 investigative report, excerpted at right, blamed these major and well-publicized downtown incidents on the "underlying racism and the breakdown in Law and Order within the Detroit Police Department." But the Ad Hoc Action Group also emphasized that most incidents of police brutality went unrecorded and were part of the everyday policing of poor black neighborhoods in the city of Detroit, including the intensifying criminalization of black youth.

The Ad-Hoc Action Group immediately protested the police violence again protesters at the George Wallace rally, quickly named Cobo II, and blamed the incident explicitly on the DPD's and mayor's failure to take any meaningful action after Cobo I. The group demanded a full investigation and argued that the police officers on the scene had violated the department's own professional standards by giving no warning for the crowd to disperse before attacking and removing their badges to avoid identification. The Ad-Hoc Action group also labeled the deployment of "uncontrolled police power" against citizens exercising their constitutional rights to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly to be an indication of a right-wing anti-democratic agenda inside the DPD.

The Ad-Hoc Action Group emphasized that the police assault at Cobo II was unjustified even though one protester had apparently been responsible for "one provocative act of unjustifiable violence," presumably the throwing of a rock at a police officer outside the Ponchartrain Hotel. In an interview conducted 25 years later, Sheila Murphy elaborated on this phenomenon, observing that "nobody who throws rocks at cops has a fundamental understanding of the nature of police power." (This also happened at Balduck Park in 1970, where the Ad Hoc Action Group defended white countercultural youth after a series of violent police assaults). Murphy pointed out that a small number of white youth radicals in the New Left were living out their revolutionary fantasies inside the city of Detroit during the late 1960s, and often making things even more difficult on the black power and community control organizations that were based there full-time. She commented that when "a white middle-class kid from out of town or some wealthy suburb somewhere" threw rocks at, and otherwise directly antagonized, the police, "you're taking advantage of your position in the culture."

The Ad Hoc Action Committee had expected police violence at the George Wallace rally in October 1968 and had dispatched 23 of its cop-watchers to be on hand as observers and peacekeepers. Sheila Murphy, who was leading the delegation, told the Michigan Chronicle that two police officers roughed her up and said, "We'd kill you if we thought we could get away with it," and that her house was ransacked, almost certainly by police, soon thereafter. The group maintained pressure on the DPD in the subsequent months and then, in spring 1969, denounced the whitewash after the complete exoneration of all Cobo II officers. The Ad-Hoc Action Group also continued to protest the minimal discipline for the officers involved in the Veterans Memorial Incident and inverted its initial slogan from the more liberal call for "law and order with justice" to a more explicitly radical demand:

Demanding Civilian Control of the DPD

The Ad-Hoc Action Group formed in the spring of 1969 after the outrageous police assault on peaceful civil rights marchers at Cobo Hall and initially appeared to believe that a political action campaign led by college-educated white youth and white religious leaders, mainly Catholic priests, could convince the liberal city administration to fully professionalize the Detroit Police Department, its stated goal, and punish overt acts of brutality and racism. They were wrong.

The full radicalization of the Ad-Hoc Action Group was an ongoing process, accelerated by the the DPD and Cavanagh administration coverups of the Cobo I and Cobo II incidents, both mass attacks by DPD officers on progressive political activists. In March 1969, the DPD's assault on and mass arrest of 142 African Americans gathered for a black nationalist political conference at the New Bethel Church (covered in the next section) seemed to be the last straw. During 1969-1970, the Ad-Hoc Action Group continued to train civilian members in its "police observation" program (right) and to lobby DPD and city government officials for the traditional civil rights reform goals of hiring more black officers, curbing police brutality, and promoting fair law enforcement. But Sheila Murphy and the other leaders of the Ad-Hoc Action Group lost all faith in the liberal Cavanagh administration and came to believe that the DPD's stated goals of police professionalism and improved police-community relations were just a public relations facade.

In summer 1969, the Ad-Hoc Action Group published "Detroit's Political Police," an expose of the influence and agenda of the DPOA union, which embraced the same critique as black power organizations and left-oriented black politicians that the police department had become "an overt political force" that was actively seeking to inflame and capitalize on racial polarization in the city. The Ad-Hoc Action Group categorized the Detroit Police Department as a "political body enforcing its own views of society on the community at large, rather than an agency under the control of the civilian community." The expose presented data from academic studies conducted after the 1967 Uprising that most white police officers were overtly racist and viewed black residents of Detroit collectively as criminals who had to be controlled by force. The Ad-Hoc Action Group portrayed a struggle for political control of the city of Detroit between three groups:

- "the 91% white, incredibly racist police department"

- "the predominantly white, moderately racist liberal faction (Mayor Cavanagh, members of the Common Council, the New Detroit Committee)"

- "the people, the members of Detroit's non-affluent, non-white community" (both Black and "Spanish American")

In the Ad-Hoc Action Group's analysis, the Cavanagh administration's failure to diversity the DPD as promised, and failure to do almost anything about repeated episodes of mass police brutality, meant that the "moderately racist" liberals, who wanted get-tough but "professional" law enforcement, had lost control of the "incredibly racist" police department that the DPOA union now dominated. In a subsequent report (below right), the Ad-Hoc Action Group went even further, labeling the city of Detroit fully part of the "American Police State."

The only solution was complete civilian control over the DPD. In the summer of 1969, the Ad-Hoc Action Group played a key role in organizing the Citizens' Police Trial Board Petition campaign, an effort to qualify a ballot initiative to amend the city charter in the election that fall. The proposal was to elect 16 civilians, one from each police precinct, to four-year terms on a commission with the power to investigate all allegations of police misconduct in hearings open to the public. The Citizens' Police Trial Board would have the final authority to order mediation or restitution and to impose discipline, up to and including termination. The Ad-Hoc Action Group worked closely with the NAACP, state senator Coleman Young, and other organizations on this proposal for a civilian review commission, which had been a primary goal of civil rights groups since the late 1950s.

The Citizens' Police Trial Board Petition failed to qualify for the ballot in November 1969. A chance for victory still seemed possible because Richard Austin, the African American mayoral candidate in the election to succeed Cavanagh, endorsed "civilian control of police" as part of his platform. But with a massive white turnout, conservative white candidate Roman Gribbs narrowly won the 1969 mayoral election on the promise to unleash the police department and launch an "all-out fight against crime in the streets." When Coleman Young did win the subsequent mayoral election, in 1973, a parallel charter amendment established a mayor-appointed board of police commissioners with limited authority, rather than an elected and autonomous civilian review committee, which turned out to be a very ineffective reform.

Examine documents from the Ad-Hoc Action Group's campaign for civilian control of the DPD in the gallery below.

Sources:

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

MaryAnn Mahaffey Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Sheila Murphy Cockrel interview in Robert H. Mast, ed., Detroit Lives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994), 181-186

Image Gallery, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press, Oct. 20, 1968, Nov. 27, 1968, Dec. 30, 1968, April 20, 1969, Dec. 1, 1970

William Serrin, "How Well Does the City Police Its Police?" Detroit Free Press, Jan. 24, 1969

"Ad-Hoc Leader's Home Is Ransacked," Michigan Chronicle, Aug. 30, 1969

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2001).