The Manhunt

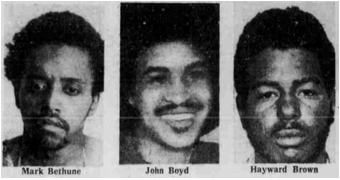

On December 4, 1972, three young Black men engaged in a shootout with four white STRESS officers during a murky encounter that took place outside a dope house. The threesome--Mark Bethune, John Boyd, and Hayward Brown--were, depending on the perspective, either activists dedicated to fighting the narcotics trade in their community or vigilantes taking the law into their own hands because the police would not. Both interpretations contain elements of truth, because the illegal narcotics market flourished with the extensive complicity of corrupt Detroit police officers, as made clear by the exposure of the Pingree Street Conspiracy a few months later.

The DPD launched a massive monthslong manhunt for the three fugitives, resulting in extraordinary abuses of the civil and constitutional rights of hundreds of Black citizens and the killing of an innocent man during one of many warrantless home invasions. Then, in late December, a white STRESS officer died in a second shootout with Bethune, Boyd, and Brown. DPD Commissioner John Nichols responded by labeling them "mad dog killers," and the manhunt escalated even further, with even worse police violence and illegality. Mark Bethune and John Boyd were eventually killed by police officers in Atlanta, while Hayward Brown was arrested in Detroit and tried for murder but acquitted. The manhunt generated the largest protest movement against STRESS to date (covered on the next page) and united every major civil rights organization in the city in a campaign for abolition of the unit. The DPD's extreme overreaction and mass criminalization of Black Detroit ultimately backfired, as the manhunt proved to be a key turning point that mobilized African American voters to defeat STRESS and the white-controlled DPD at the ballot box in the 1973 mayoral election.

The Dope House Shootout

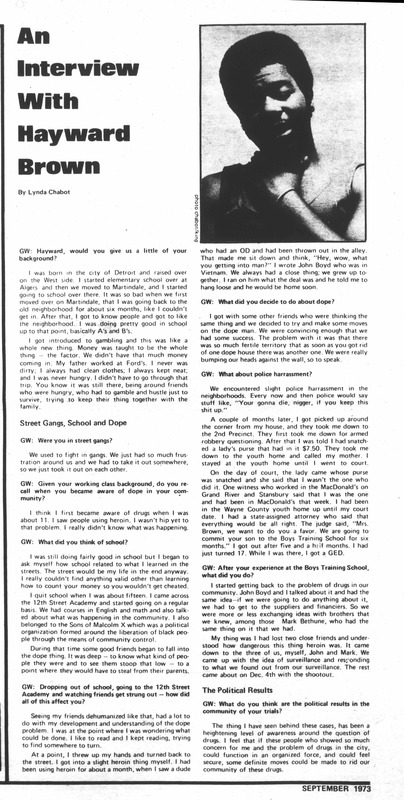

Mark Bethune, John Boyd, and Hayward Brown lived on the West Side of Detroit in segregated Black neighborhoods they felt were being ravaged by narcotics trafficking. The three young men--ages 22, 23, and 18, respectively--became prominent in the community as avowed enemies of street dealers and narcotics criminals. In a 1973 interview (gallery below left), Hayward Brown explained that he had grown up in a tough neighborhood and seen several of his good friends succumb to heroin addiction, and even briefly experimented with the drug himself, before he decided to team up with his cousin John Boyd, a Vietnam War veteran, and "make some moves on the dope man." Brown expressed frustration that "as soon as you got rid of one dope house there was another one" and also described DPD harassment of them for their efforts. Eventually he and Boyd teamed up with Mark Bethune, another anti-narcotics crusader who had reportedly received weapons training from the Black Panthers and the Republic of New Africa, a black nationalist organization based in Detroit. Bethune was a suspect in the recent abduction and murder of a known drug dealer, which John Boyd and Hayward Brown may or may not have realized. Together they decided to escalate the anti-dope campaign by going after the "suppliers and financiers."

On December 4, 1972, the three men decided to take vigilante action against a known dope house run by John Crawford, a major heroin distributor. When the threesome arrived, an undercover team of four white STRESS officers was also staking out the location. (The STRESS team stated that they were following procedure as part of the unit's anti-narcotics mission, but skeptical community activists later wondered if the officers might have been engaged in corruption, perhaps even protection of the Crawford operation. There is no direct evidence of this).

What happened next took place in the dark of night and is both contested and unclear. The three Black activists were following Crawford, the dope house supplier, in their car when the unmarked STRESS patrol team forced them off the road. Bethune, Boyd, and Brown did not appear to realize that the armed men who were attacking them were police officers and believed that they might have been Crawford's henchmen. The STRESS officers claimed that they thought the car carrying Bethune, Boyd, and Brown was leaving the dope house and contained drug criminals and contraband. Both sides began shooting at the intersection of Livernois and West McNichols. It seems likely that Mark Bethune fired first, although Hayward Brown testified that STRESS did in his later trial. All four of the STRESS officers suffered gunshot wounds during the shootout, and the three Black men fled the scene.

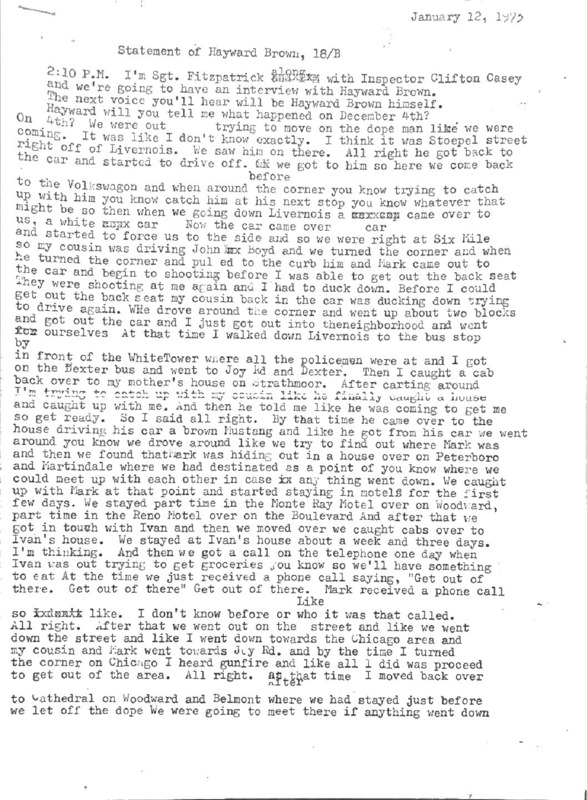

- Hayward Brown, an 18-year-old African American male, was the only one of the threesome to survive the police manhunt and provide a firsthand account of what happened that night. Brown gave an initial statement to the DPD after his arrest on January 12, 1973 (gallery below, second from left). It is worth assessing this statement with the knowledge that multiple DPD officers beat Brown while he was in custody. Brown explained that "we were out trying to move on the dope man," following him in their vehicle, when a white car "started to force us to the side" of the road. As they pulled to the curb, Mark Bethune got out and began shooting, and the other men [the plainclothes STRESS officers] also were shooting at them. It is not clear from Brown's initial account who fired first, although in his subsequent trial for attempted murder, he testified that the STRESS team had opened fire first, "without provocation." The threesome then fled the scene and began hiding out in motels and in a friend's house, until the second shootout in late December (covered below).

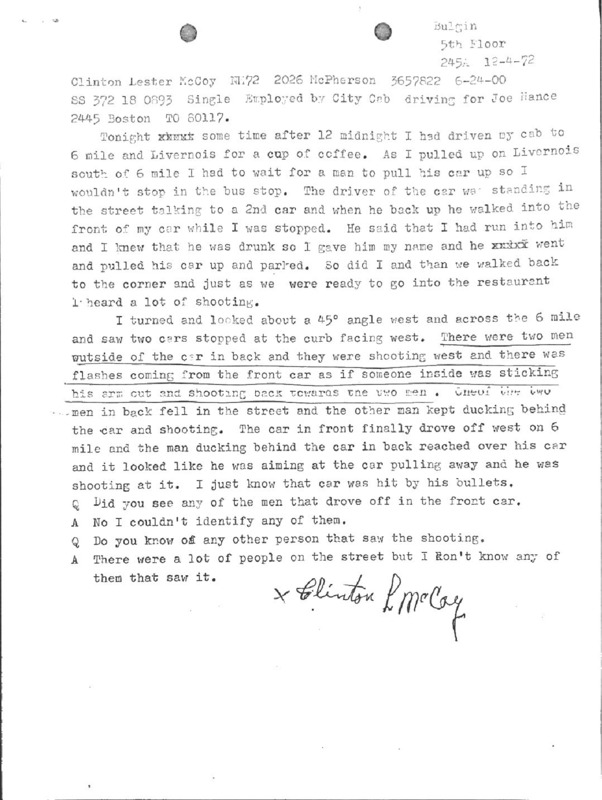

- Clinton Lester McCoy, a 72-year-old African American man, witnessed the shootout and gave a statement to the police investigators (gallery, second from right). McCoy, a cab driver, described two cars stopped on the side of the street, with two men [presumably Boyd and Bethune] outside of their vehicle using it as a shield and firing at the occupants of the other car, who were also firing back from the inside. McCoy emphasized that it was too dark to identify any of the participants in the encounter.

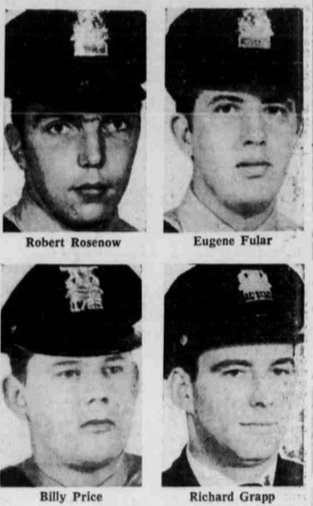

- Patrolman Billy Price, a 32-year-old white STRESS officer, said that the undercover team was tailing a car of suspects who had just left a known dope house and in the process of pulling them over when a man jumped out of the front passenger seat and began firing a pistol, wounding him in the leg. Price stated that he began to fire back, without aiming. Price also saw Patrolman Richard Grapp, the driver of their car, hit in the chest "before he knew what was happening." Patrolman Eugene Fular tried to respond but was wounded by multiple shotgun blasts. Patrolman Robert Rosenow fired several shots at the suspects from inside the unmarked police car.

DPD Ransacks the Black Community

The Detroit Police Department immediately launched a massive search for the three fugitives and described them to other law enforcement agencies as "armed and extremely dangerous" and committed to "shoot any police officer on sight." It is highly doubtful that the DPD had reliable information to this effect, and describing the three Black males as bloodthirsty cop-killers therefore served to justify the intense manhunt and the widespread abuses of civil liberties and constitutional rights that followed. Commissioner John Nichols speculated that the suspects, who faced assault with intent to murder charges, either were driving a "guard car" for a major heroin shipment or were hit men hired by a rival trafficker to execute the dope house target. (The DPD later conceded that it could neither confirm nor deny that the threesome were "vigilantes fighting the drug traffic").

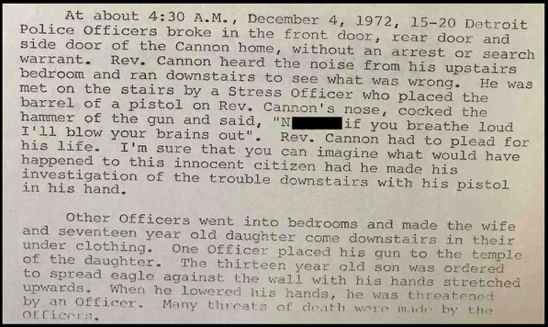

Teams of DPD officers immediately ransacked dozens of private homes in warrantless raids, claiming to focus on residences connected to the narcotics trade, but in fact terrorizing a wide range of Black civilians and leading to a deluge of complaints. At 4:30 a.m. on Dec. 4, just a few hours after the shootout, around 15-20 STRESS and DPD officers invaded the home of Rev. Leroy Cannon and his family, breaking down three doors without a search warrant and holding guns to their heads, including his teenage children. STRESS officers yelled racial epithets at Rev. Cannon and repeately threatened to kill him and his wife and children, as described in a formal complaint sent to Commissioner Nichols two days later (excerpt at right; read full letter here).

The police abuses on the first night were only a prelude to the intense manhunt that commenced after the DPD identified the three suspects and began to target their families, friends, acquaintances, and a sizable number of people and places with no connection to them at all. This included mass stop-and-search procedures as police officers with guns drawn detained young Black men, on foot and in cars, who 'resembled' the fugitives. On December 14, six family members and friends of John Boyd and Hayward Brown filed a lawsuit accusing the DPD of illegal home invasions, warrantless searchers, interrogations at gunpoint, wrongful arrests, and harassment of those who protested. The plaintiffs expressed fear that police officers would kill them and asked for a restraining order against the entire department. Odessa Brown, Haywood's mother, also stated in the lawsuit that STRESS officers told her "they would shoot her son on sight." Family members of John Boyd accused a DPD officer of threatening to blow up their home and said that, after a group of officers held them at gunpoint, a second group came to apologize the next day and warned them that white policemen were plotting to kill him even if he surrendered. (The judge did issue the restraining order on Jan. 11).

Homicide of Durwood Foshee. Two days after the shootout, at least 28 STRESS officers and other policemen invaded the home of Durwood Foshee on a false tip and killed him in his bedroom while firing at least 90 shots. Foshee, a 57-year-old African American man, was asleep when the police officers stormed his house at 2:10 a.m. The DPD officers tried to cover up what happened, claiming that they knocked on the door and identified themselves and were still on the front porch when Foshee fired a shotgun blast at them out of a window and then refused to drop his weapon. Foshee's family insisted that the police account was a fabrication, and the forensic evidence demonstrated that he was in his bedroom when killed and probably did not fire the shotgun (the DPD did not run a ballistics test, a glaring irregularity). The Wayne County Prosecutor exonerated the police officers, although the Foshee family later received a $1.4 million jury award in a wrongful death civil lawsuit. (For more detailed analysis, visit the STRESS Victims page).

The manhunt generated many other abuses, although only a few Black citizens chose to file official complaints, either out of fear of police retaliation or a recognition that an internal DPD investigation would not make any difference. In several cases documented by the Michigan Chronicle, anonymous Black females accused STRESS and other DPD officers of sexual and physical abuse during warrantless home invasions. This included several different groups of college students forced to undress at gunpoint after police officers kicked in the doors of their apartments and alleged that they were looking for hidden weapons under their clothes. Another anonymous man reported that he was driving on the East Side with his daughter when the police stopped and searched him and then, when he protested, slapped him in the face and said "you don't ask me no goddam questions." A 15-year-old male told the Chronicle that a group of plainclothes officers in an unmarked car held a gun to his head and said, "tell me where Boyd and Brown are." A 13-year-old male walking home from school was chased by an officer who pulled out his gun, yelled a racial slur, and said "we're tired of you people shooting us."

The interactive map below illustrates 19 formal complaints made by African American citizens against DPD officers between Dec. 4, 1972, and Jan. 2, 1973, the first month of the manhunt. The incidents are compiled primarily from the files of the DPD's Citizens Complaint Bureau, found in the papers of Mayor Roman Gribbs, and from Michigan Chronicle articles in which the citizens provided their names and locations. The majority took place during the week after the first shootout, and most involved warrantless home invasions at night, often of family members or acquaintances of Bethune, Boyd, and Brown. In a number of cases, DPD officers held terrified residents at gunpoint, threatened to kill them, used racial epithets, committed property damage, and made wrongful arrests. It is important to emphasize that these formal complaints only represent the tip of the iceberg, as many African Americans did not believe that asking for an internal DPD investigation would make any difference. A large number of Black citizens detailed stories of abuse at the Jan. 11 city council hearing covered below, most of which are not included on this map because they chose not to provide their names and/or addresses. The DPD's internal investigation found all of these formal complaints to be "unjustified," and at most paid for minor property damage while denying any other wrongdoing. Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols strongly defended the "vigorous" tactics of the police department during the manhunt, as examined below. On Feb. 15, 1973, a Recorder's Court judge ruled that 56 specific warrantless DPD searches during the manhunt had been illegal, including most if not all of the ones included on this map.

19 Formal Citizen Complaints to DPD regarding Abuses during the Manhunt

The blue-shaded areas represent majority-Black or all-Black neighborhoods, based on the 1970 census.

- Black dots = Police Brutality

- Red dots = Police Misconduct

The Second Shootout and Community Protests against the Manhunt

On December 27, a second shootout between the manhunt suspects and white STRESS officers resulted in the death of Patrolman Robert Bradford and the critical wounding of Patrolman Robert Dooley. By then, the news media had widely reported that the DPD was operating under "kill on sight" orders, which would have made the fugitives even more determined not to surrender. The two officers were part of a STRESS team that was staking out a house believed to be connected to the suspects when they were fired upon by assailants who then fled. The officers fired back and probably wounded one of the men. At least one witness said a suspect fired point-blank at an injured officer, presumably Bradford, who was lying on the ground. The DPD publicly identified John Boyd and Hayward Brown as the shooters in the incident and also arrested Ivan Williams, a Wayne State University student, for harboring the fugitives in his house (a judge dismissed the charges). Later, the DPD said that all three of the suspects in the Dec. 4 shootout were present for the second encounter on Dec. 27.

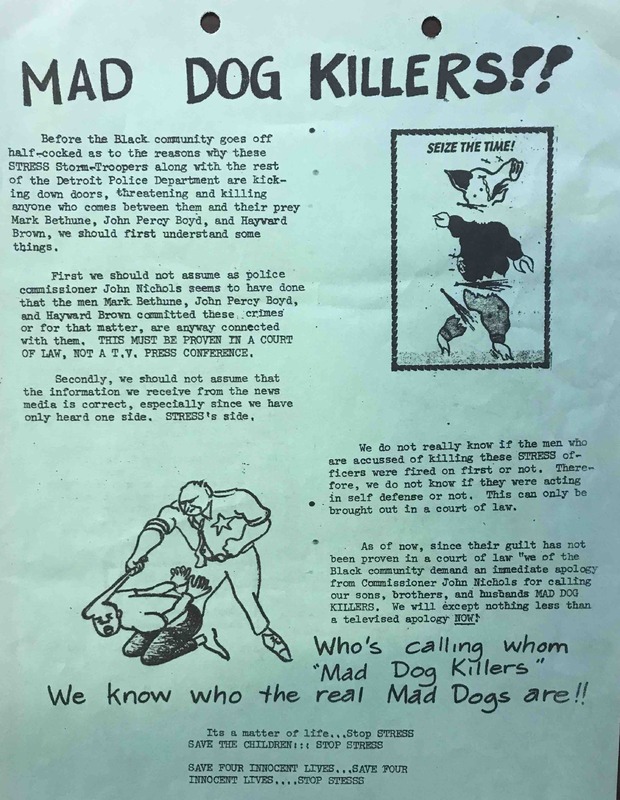

"Mad Dog Killers." Commissioner Nichols labeled the African American fugitives "mad dog killers" and declared that the city of Detroit was "like a battle zone." The DPD assigned 50 Homicide Bureau detectives to the investigation and mobilized hundreds more officers in what it called the "most intensive" manhunt in the city's history. Nichols and Mayor Roman Gribbs also threatened severe punishment for any Detroit residents found to be harboring the suspects. The DPD launched a house-by-house search of the area on the West Side of Detroit where the incident occurred and then continued to expand its dragnet across African American neighborhoods in the city.

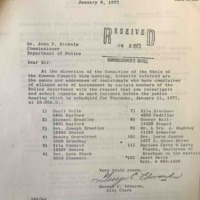

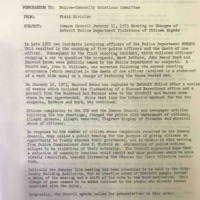

"Unconstitutional Police Action Challenged." The escalation of the manhunt produced a new round of police abuses and also generated a massive outcry from civil rights organizations and regular Black residents of Detroit. On January 4, a coalition including the NAACP, ACLU, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Guardians of Michigan released a statement denouncing the Detroit Police Department for victimizing the Black community through its unconstitutional manhunt. The coalition demanded that the mayor and city council convene a public hearing to examine the complaints of citizens who had suffered illegal home invasions, wrongful arrest, physical and verbal abuse, and a mass stop-and-frisk crackdown in the streets. The statement concluded that the DPD's manhunt was a "dangerous precedent for the abolition of liberty" (gallery below, left).

The Michigan Chronicle, a relatively moderate publication, condemned the manhunt as the worst DPD abuse since the crash crackdown that victimized thousands of innocent Black citizens during 1960-1961. Reporter Bill Black filed a column accusing the police officers who were enraged by the murder of Patrolman Bradford of acting like "hard-core criminals," in short just like those they claimed to be fighting. He also wrote that while the manhunt fugitives should be brought to justice, the unjustified homicides committed by the STRESS operation were directly responsible for setting the current cycle of deadly violence into motion. Bill Black concluded:

The theme that Black lives did not matter as much as white lives, and that police lives mattered far more than Black civilian lives, pervaded the response in the African American community. Nadine Brown, another columnist for the Michigan Chronicle, wrote of the "wave of police terror" that "when a policeman is killed, the Police Dept. goes berserk, but when a citizen is killed by police it is justifiable regardless of the circumstances" (full column in gallery below).

The Guardians of Michigan, the association of Black police officers, issued yet another demand that STRESS, "this 'elite' unit of hoodlum policemen," be abolished (right). The Guardians further characterized the manhunt as a "reign of terror upon the honest citizens of the Black community," and its president Tom Moss warned that the DPD had unofficially but clearly communicated "kill on sight" orders to its officers. In response, the Guardians publicly appealed to the three fugitives to surrender to Black officers in order to be safe from reprisals by white members of the DPD.

The radical wing of the anti-STRESS movement portrayed Boyd, Bethune, and Brown as community heroes who had acted in self-defense against both drug dealers and their corrupt police allies. They circulated flyers labeling STRESS a genocidal operation and depicting the fugitives as "Black brothers who are putting intensive pressure on dope pushers and their associates to get out of the Black community" (left). Another flyer called the three men "heroes of the people" for battling the narcotics dealers that the "police department has refused" to confront and concluded, "STRESS Is the Dopeman!!" (right). A third (linked here) labeled STRESS to be the real "Mad Dog Killers" and demanded that the guilt or innocence of the fugitives be determined in a court of law rather than the probability that the police would gun them down in the streets.

City Council's Manhunt Hearing. Under pressure from African American members, the Detroit city council agreed to hold a Jan. 11 public hearing allowing citizens to testify about the DPD's manhunt abuses. Mayor Gribbs and Commissioner Nichols initially refused to attend but relented under threat of subpoena. Before the event, Gribbs issued a press statement (gallery below, second from right) promising that the DPD would investigate the charges made by Black citizens and discipline any officers who violated rules and procedures. But the main agenda of the mayor's statement was to defend the DPD and the need for "vigorous professional legal police efforts" in order to apprehend the dangerous cop-killers on the loose.

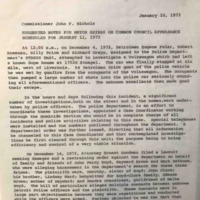

In preparation for the event, Commissioner Nichols provided the mayor with a confidential report on the manhunt (gallery, below right) emphasizing that it had nothing to do with race because white and Black police officers were equally outraged at the actions of the fugitives. Nichols also stated that DPD officers had engaged in proper behavior at all times, and that any armed entry into private homes without a warrant had taken place under the "probable cause" justification of hot pursuit (a very debatable claim).

In his public remarks at the hearing (right), John Nichols spoke dismissively and confrontationally to the overwhelmingly Black crowd, which responded in kind by shouting him down repeatedly. The DPD commissioner, who was preparing a run for mayor on a pro-STRESS platform, did not even try to build bridges to the outraged citizens in the audience and presumably believed that his main political imperative was to mobilize white voters by polarizing the relationship between the police department and Black Detroit. Nichols also deployed a large contingent of DPD officers to provide 'security' at the hearing, and all of them were white, which drew criticism from members of the audience.

Nichols opened by stating that he did not even need to justify the "lawful rights of a police officer" to enter a private home without a warrant under the probable cause doctrine. The commissioner then denied that the DPD was engaged in a racial "crackdown" and instead called the manhunt a targeted operation against three very dangerous individuals, including one [Bethune] also suspected in the murder of a Black man [an alleged drug dealer]. Nichols then demanded that the full community join with the police department to apprehend the murderers. In his prepared remarks, Nichols even blamed the home invasions made in error on false tips provided to the DPD by critics who wanted to "embarass the police [and] impede the investigation." And he concluded the statement by criticizing "our citizens," meaning Black citizens, for turning the "side issue of possible police misconduct" by a few officers, which the commissioner insisted was minimal if real at all, into wholesale "indictments of the entire Department." Commissioner Nichols never got to these final points at the hearing itself because the jeering crowd forced him off the stage before he could finish.

Black Citizens Push Back. Around 1,200 people attended the city council hearing, and many attacked Commissioner John Nichols and denounced the DPD, the manhunt, and the STRESS operation as part of a single reign of racist terror. A full transcript of the hearing exists in Mayor Roman Gribbs's papers, providing a remarkable document revealing the depth of anger and resentment toward the DPD, and the political mobilization that the police crackdown produced, among a broad cross-section of Black citizens of Detroit. The relatives and friends of the three fugitives received the first speaking slots, and they told harrowing stories of a violent and out-of-control police department on a mission of indiscriminate revenge without regard for the law or the constitution. Other members of the African American community joined in with a broad spectrum of grievances and demands for a radical transformation of the DPD and city politics more generally. The transcript must be read to be fully appreciated and is reproduced in its entirety in the gallery below, with only a few highlights emphasized here.

- The first audience member who spoke interrupted the city council's discussion of the ground rules to ask what would happen when DPD officers "come and kill everybody" who provided evidence of STRESS abuses. The audience then laughed and jeered at a council member's suggestion that Commissioner Nichols give assurances that the police would protect all witnesses from such threats.

- The second speaker also interrupted and yelled out, "I have fought for your country, I have got shot, me and my lady can't stay home in peace without some of your police officers kicking in my door."

- Melba Boyd, the first official citizen witness, was John Boyd's sister and Hayward Brown's cousin. She described the police breaking into her family's home and holding guns on her and her 2-year-old brother, whom they also handcuffed. She also accused the DPD of keeping her under surveillance since Dec. 4.

- Dorothy Clore, the mother of John Boyd and a public school teacher, opened by saying "I am not ashamed of my son. He is not a criminal." Instead she portrayed the DPD as the real criminals, describing how around 15 policemen broke into her apartment, pointed rifles at her and her children, "scared the plain hell out of me," illegally searched the residence and took her possessions, and had harassed her constantly ever since. Dorothy Clore then said that this extreme reaction happened "because I am black" and would not have happened in a white part of town if a white male--she proposed Commissioner Nichols's own son--was a suspect in a similar crime. She also told Nichols that if her son did want to surrender, the police department could not be trusted to keep him alive.

- John Clore, the stepbrother of John Boyd, described 10 police cars coming to his house, handcuffing him at gunpoint, destroying his possessions, and arresting him for "resisting arrest." He said he feared for his life, "like all these other ones they shot and murdered." The one Black officer present whispered to him, "be cool man, these dudes want to kill you." John Clore also accused the DPD of lying to the public that the three fugitives were narcotics criminals "when they all know that these guys were in the community trying to get rid of dope." He further described constant police stop-and-frisks in the weeks since, every time he left the house on foot or in his car.

- Kenneth Cockrel, the Labor Defense Coalition attorney in the anti-STRESS lawsuit who also later represented Hayward Brown, interrupted the proceedings at one point to yell "get rid of Gribbs, get rid of Nichols." Cockrel tried to present the council with a box of 30,000 signatures from the petition drive to "Abolish STRESS" but DPD officers stopped him when he got to the stage.

- Around two dozen additional speakers described police breaking into their homes, holding them at gunpoint, threatening their lives, using racist slurs, and ordering women to remove their clothes. Speakers denounced STRESS for murdering teenagers in the street and killing Durwood Foshee inside his home. Speakers accused the DPD of corruption in the narcotics traffic and wanton brutality in traffic stops. Speakers described the police pulling guns on their teenage sons out on the street because they 'looked like' one of the fugitives. Speakers called on Black people to "organize to protect ourselves," and many demanded the abolition of STRESS. Multiple speakers called Commissioner Nichols and STRESS officers "mad dog killers," turning the description of the fugitives back around on its author. One speaker, a cousin of Mark Bethune, defended the fugitives for trying to stop the dope trade and concluded, to some applause, "long live Boyd, Brown, and Bethune." Toward the end, an unidentified speaker proclaimed:

The Arrest and Trial of Hayward Brown and End of the Manhunt

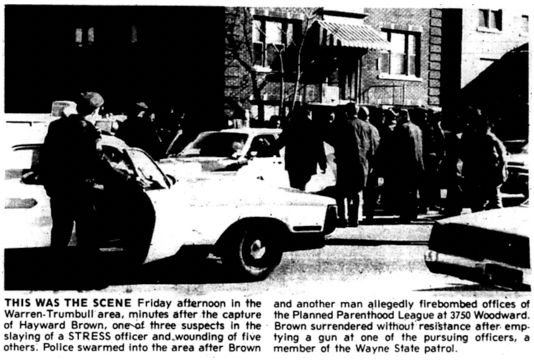

The DPD arrested Hayward Brown, the youngest of the three fugitives, on January 12, the day after the city council hearing. Brown, along with John Boyd and Mark Bethune, firebombed a Planned Parenthood office building in front of multiple witnesses. Hayward Brown allegedly fired several shots at a Wayne State University campus officer before surrendering without resistance to a DPD patrol car. The police report released to the media stated that "Brown struggled violently and had to be subdued." An eyewitness told the Michigan Chronicle that, in fact, after the patrol car detained and handcuffed Hayward Brown, DPD officers arrived on the scene from many directions and "they kicked him and stomped him, hit him with rifle butts and flashlights."

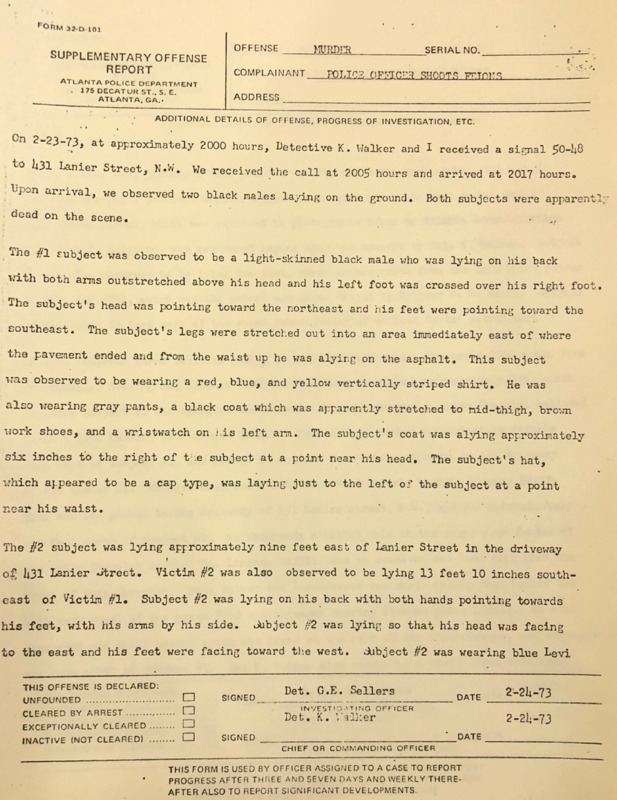

John Boyd and Mark Bethune were not apprehended that day and left Detroit at some point over the next couple weeks. Both men ended up on the FBI's "Most Wanted" list and also in the city of Atlanta, where they were shot by police officers in separate incidents. John Boyd and his stepbrother, Owen Winfield, were shot and killed by an Atlanta Police Department officer on February 23 (view the incident report here). Mysterious circumstances surrounded the episode, because a witness said that an unidentified man fired a single shot at both Boyd and Winfield as they lay wounded, and ballistics tests showed the bullets did not come from the gun of the police officer credited with shooting both of them. The Atlanta Police Department publicly named Mark Bethune as a suspect in this additional shooting, but Black community activists believed that a second police officer had executed the two men after they were wounded, and the bullets did not match Bethune's favored .357 magnum. The third fugitive died four days later, on Feb. 27, after being badly wounded in a shootout on the roof of a college building in the Atlanta University center. As police officers closed in and helicopters circled overhead, Mark Bethune killed himself with his own pistol.

Murder of Robert Slaughter. On February 9, during the continuing manhunt for Mark Bethune and John Boyd, a white DPD officer stopped Robert Slaughter, a 29-year-old Black male, as part of the "stop-and-search" racial profiling operation to find the fugitives. Slaughter was walking down the street when detained, and he reportedly responded by shooting and wounding Patrolman Gregory Ciaglo. Multiple DPD squad cars rushed to the scene, and one officer shot Slaughter in the leg after he allegedly threatened them with a gun. The group of policemen then proceeded to beat and kick Slaughter while he was in custody, and he died in the hospital after falling into a coma. The officers claimed that he had resisted arrest. The medical examiner ruled Slaughter's death to be a homicide by blunt force. Slaughter's family and many Black activists in the anti-STRESS movement protested that the police had committed an extrajudicial execution in the street. Katie Crew, Slaughter's mother, told the Michigan Chronicle that "they beat my son to death." The DPD refused to release the identities of the officers involved and, along with the Wayne County Prosecutor, protected them from consequences.

Heroes or Criminals? The end of the manhunt, and the subsequent trial of Hayward Brown, intensified a debate in the Black community about whether the three fugitives were heroes, criminal villains, Robin Hood-style vigilantes against the drug menace, or some combination of all three. Nadine Brown, a popular columnist for the Michigan Chronicle, asked "Mark Bethune--Jekyll or Hyde?" in the coverage of his funeral. A leader of the Republic of New Africa, a black nationalist group, provided the eulogy and praised Mark Bethune for being willing to die in order to "move against the dope man" and stop the flow of narcotics that was devastating the poor Black neighborhoods of Detroit. Kenneth Cockrel also spoke and urged the crowd to fight against the heroin plague so that Bethune and Boyd would not have "died in vain." Regular people wrote letters to the Chronicle praising the three men for "trying to help the Black community get rid" of the dope dealers, which "we all know is in the police department as well as on our corners." At John Boyd's funeral, his mother Dorothy Clore said that the three men "gave of themselves to you and to all our people who are oppressed." She concluded, "Let us get the kids off the streets. Let us get rid of the dope. Let us leave the white man's evil to the white man."

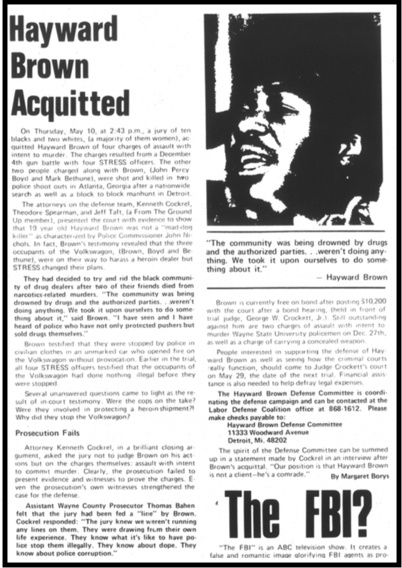

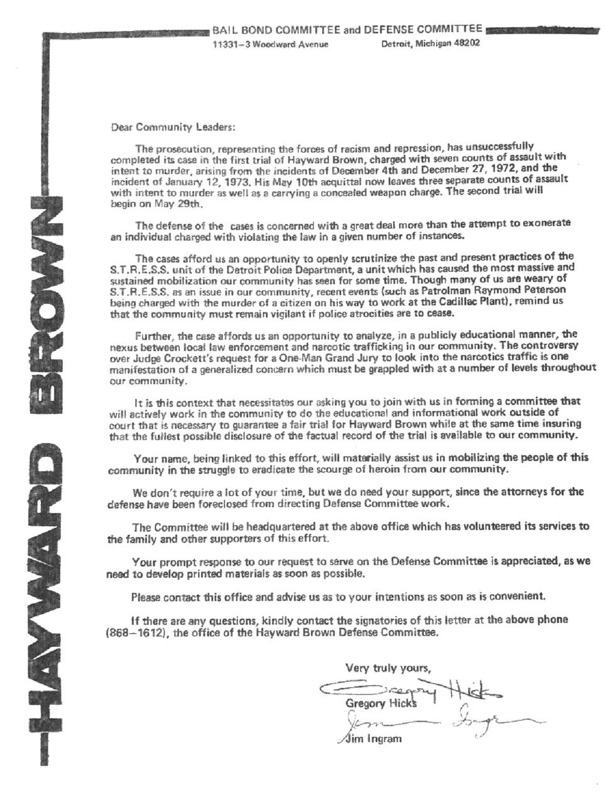

The 3 Trials of Hayward Brown. The Wayne County Prosecutor charged Hayward Brown, the only survivor of the manhunt, with seven counts of assault with intent to commit murder and one count of first-degree murder of Patrolman Robert Bradford, leading to three separate trials for the three armed encounters with police officers. Kenneth Cockrel and the Labor Defense Coalition, the attorneys at the center of the anti-STRESS movement, represented Brown and embarked on a political campaign to criminalize the DPD and turn the defendant into a working-class hero who stood up to the dope dealers and their corrupt police enablers. They created the Hayward Brown Defense Committee and portrayed the real issues in the trial as the murderous history of STRESS and the "nexus between local law enforcement and narcotic trafficking in our community" (gallery below, second from right). The news of the Pingree Street Conspiracy, revealing widespread DPD criminality in the narcotics trade, broke during the lead-up to Hayward Brown's trials and made this a particularly effective strategy for the anticipated majority-Black juries that would decide his fate. The trials also took place during the massive anti-STRESS protests organized by the United Black Coalition in the spring of 1973 (covered on the next page), which intensified the political stakes for the prosecution of a Black man charged with attacking white police officers.

On April 6, Judge Samuel Gardner dismissed the first-degree murder charge for the shooting of Patrolman Bradford in the second shootout, stating that not "one scintilla" of evidence existed linking him to a premeditated killing. In response, Prosecutor William Cahalan unsuccessfully sought to have Judge Gardner, who was African American, removed from the case for bias. Hayward Brown then stood trial for assault with intent to murder the four STRESS officers during the initial Dec. 4 shootout. Brown claimed self-defense and testified that four men whom they did not realize were police officers had run their car off the road and opened fire first on him and his companions "without provocation."

The Labor Defense Coalition sought to put STRESS on trial as a corrupt shoot-first unit and presented testimony from Brown that "the community was being drowned by drugs and the authorized parties . . . weren't doing anything. We took it upon ourselves to do something about it." The defendant, and his attorneys, emphasized the pattern of police officers who "have not only protected pushers but sold drugs themselves" and implied (without specific evidence) that the STRESS patrol team might have been protecting the dope dealer that Boyd, Bethune, and Brown were tailing. All four of the wounded STRESS officers testified and denied shooting first but also acknowledged that the occupants of the vehicle had done nothing illegal when the unmarked police car tried to maneuver them off the road, which strengthened the defense's case. On May 10, a jury with 10 black and 2 white members acquitted Brown of all charges. At the trial's culmination, Kenneth Cockrel rejoiced:

Hayward Brown was subsequently acquitted by a jury for assault with intent to commit murder in the second Dec. 27 incident, claiming that the police shot first. He was acquitted again in a third trial for attempted murder for shooting at the campus police officer on the day he was arrested. Brown testified that he feared for his life because he believed that the DPD would execute him behind closed doors if he surrendered. After the third acquittal, Prosecutor Cahalan denounced the jury for a "miscarriage of justice" and personally attacked defense attorney Kenneth Cockrel and Judge Samuel Gardner, both of whom were African American. Several jurors told the Michigan Chronicle that they did not believe that Hayward Brown ever intended to kill anyone and that they also took into consideration that DPD officers clearly beat and kicked him after the arrest and then lied about it. The jurors also stated that the testimony from Brown's family members that the DPD terrorized them during the manhunt weighed on their minds in reaching the not guilty verdict.

The gallery below contains additional documents about the end of the manhunt and the anti-STRESS movement's successful politicization of the trials of Hayward Brown.

Sources:

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Groundwork, The American Radicalism Collection: Part 4: Twentieth-Century Social, Economic, and Environmental Movements, Michigan State University, Political Extremism & Radicalism, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8Dgti1

Detroit Free Press, Dec. 5-6, 15, 28-29, 1972, Jan. 27, Feb. 27-28, 1973, May 14, 1973

Michigan Chronicle, December 16, 23, 30, 1972, January 6, 13, 20, March 10, 24, June 30, July 14, 1973

Detroit News, January 17, 1973

The Militant, May 4, 1973

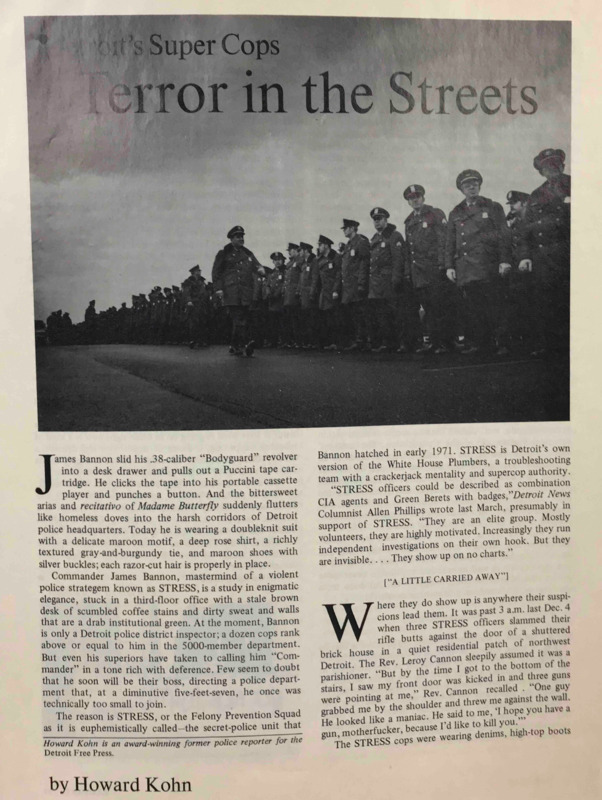

Howard Kohn, "Terror In the Streets: Detroit's Super Cops," Ramparts (Dec. 1973), 38-41, 55

Robert Slaughter in Michigan Chronicle, Feb. 24, 1973

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2001)