Stop and Frisk: Racial Profiling

The practice of stop and frisk has been utilized by American law enforcement since long before the landmark Terry v. Ohio Supreme Court decision of 1968 formalized the practice. Some cities, including Detroit, passed laws authorizing police departments to conduct stop and frisk operations, while others allowed the practice to thrive without formal laws in place, through the wide discretion that officers enjoy on the street. Stopping and frisking entails questioning, searching, and often detaining civilians who exhibit some form of suspicious behavior, at least in the discretionary assessment of the law enforcement officer. Arguments around stop and frisk center on the constitutionality of a practice that seems to limit a citizen's right to protection against unreasonable search and seizure, as guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment. In practice, stop and frisk procedures have involved systematic racial profiling, and police departments have particularly targeted them both in segregated Black neighborhoods and against nonwhite motorists and pedestrians in racially mixed areas such as downtown business districts and other commercial settings.

In the Terry v. Ohio ruling, the Supreme Court held that if an officer has "reasonable suspicion" that the individual has committed or is about to commit a crime, or otherwise poses a threat to the officer or others, then a stop and search is constitutional. In short, the officer does not need "probable cause" but can stop anyone based on a "reasonable suspicion" that is defined by the individual officer's own discretionary sense of what is reasonable. This decision aimed to protect the public from dangerous individuals, but the legal authorization of stop and frisk by the Supreme Court also led to widespread police abuses and rampant racial profiling throughout the country and in the city of Detroit. The practice, while formally codified in 1968 by the liberal Cavanagh administration, had a much longer history in DPD policies of unconstitutional racial profiling, illegal 'investigate arrests,' and other targeted crime crackdowns against Black residents.

Detroit's Stop and Frisk Law Timeline, 1965-1968

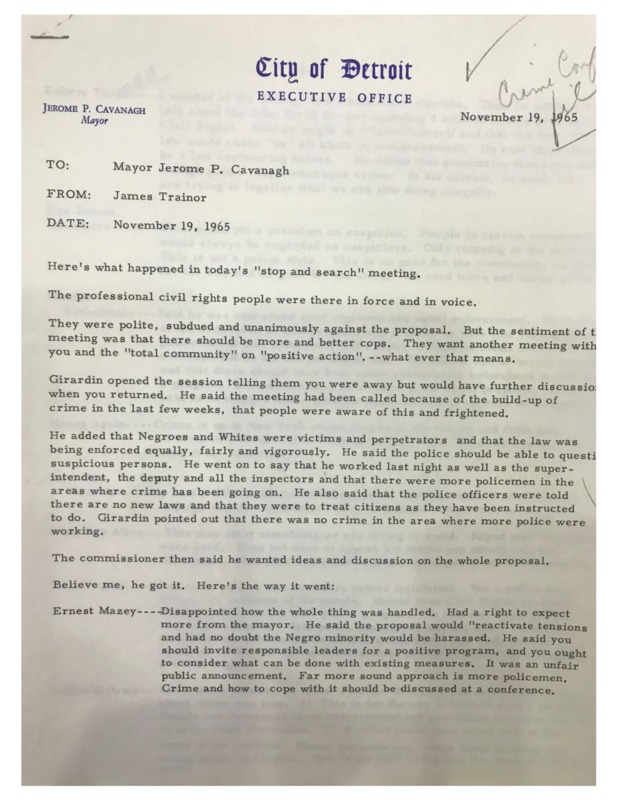

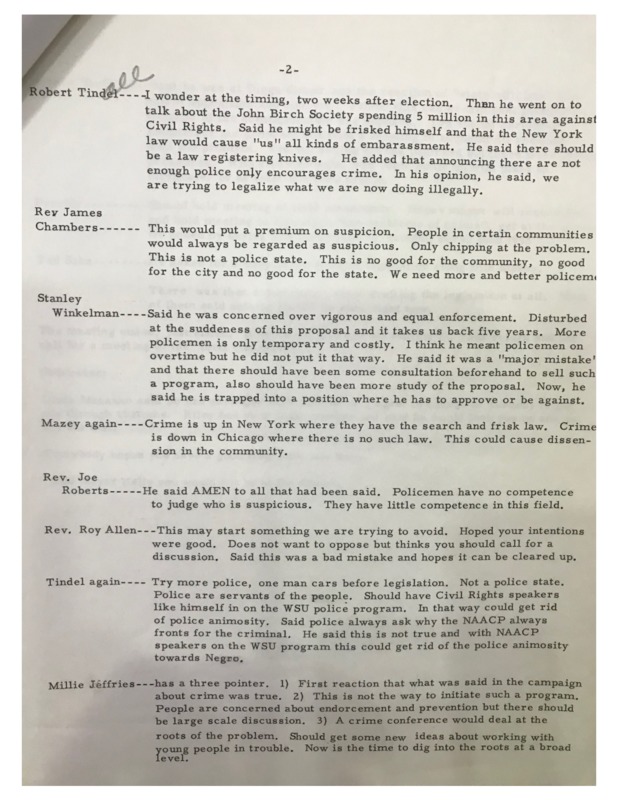

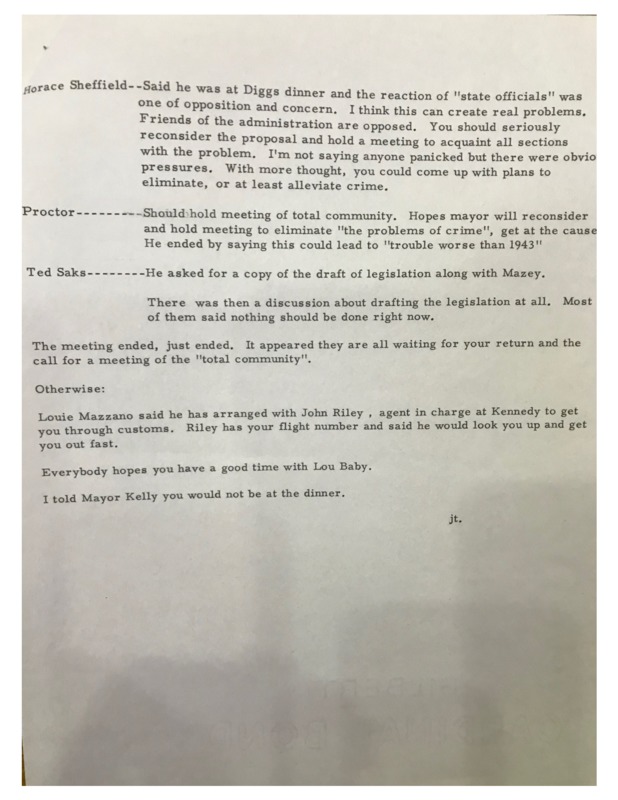

Mayor Cavanagh's stop and frisk proposal sparked city-wide debate. The Common Council was divided over the measure, although a majority did endorse a state law. One vocal opponent, African American councilman Nicholas Hood, questioned the constitutionality of such an invasive law and also argued that Detroit was not experiencing a crime wave. Cavanagh responded by calling for a crime conference to analyze the stop and frisk proposal and enlisted the support of Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to show that the Lyndon Johnson administration agrees with his get-tough crime policies.

1966-1967: Political Turmoil

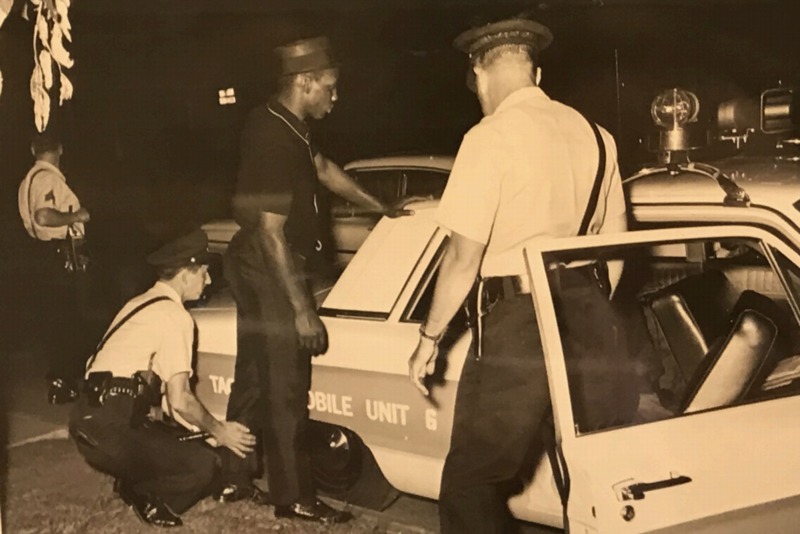

The stop and frisk debate continued to rage in 1966. In January, Detroit Free Press reporter John Millhone took a ride-along with officers from the Tactical Mobile Unit and described their frequent stops and searches of citizens on the street, with or without a law authorizing the procedure. The officers assured the reporter that stop and frisk was a common DPD tactic and believed that they did not need a law for the practice to thrive. The Cavanagh administration, however, was likely worried about civil lawsuits and other protests alleging police misconduct, which helps explain the logic of passing a law to formalize an already widespread practice.

Also in January, civil rights groups conducted a study of stop and frisk, by the Police-Community Relations subcommittee of the Citizen's Committee for Equal Opportunity (CCEO). The report argued that stop and frisk was not constitutional, would lead to widespread discrimination against law-abiding black citizens, and would not reduce crime.

Mayor Cavanagh, now worried about the unanimous opposition of African American groups and leaders, responded by claiming that he had never formally supported the stop and frisk law that he had proposed the previous November. Shortly after the release of the CCEO study, Attorney General Katzenbach backed out of Cavanagh's crime conference, probably because the Johnson administration realized the political liability in alienating African American civil rights leaders and Democratic politicians in Detroit. Then in April, state lawmakers in Lansing rejected a statewide stop and frisk law, and Cavanagh's proposal seemed dead.

In February 1967, Republican state senators proposed a large anti-crime legislative package that included a law allowing stop and frisk, anti-riot strategies, and weapons restrictions. Notably, Mayor Cavanagh and Commissioner Girardin did not openly suport this Republican proposal, even though both had championed a stop and frisk law before the backlash by Detroit's black leaders.

In Detroit, support for the stop and frisk law was growing among white residents and politicians. Councilwoman Mary Beck, a white Democrat, attacked Cavanagh for being too soft on crime and argued that the DPD needed additional authority to "put terror in the hearts of criminals." Former DPD Commissioner Edward Piggins, now a Wayne County circuit court judge, testified to Congress that stop and frisk would not lead to an abuse of police authority but would rather help police remove guns and criminals from the streets. Then came the racial unrest of July 1967, which changed the political dynamics again.

July 1967-1968: The Uprising Changed Everything

The Uprising of July 1967 led to major changes in how Detroiters perceived crime in their city, especially among white residents, and created great momentum behind get-tough measures and punitive policing. Although civil rights groups blamed police harassment for triggering the civil unrest, many white Detroiters in particular came to believe that tougher policing and widespread stop and frisk policies might have allowed the police to detain criminals carrying guns. In early 1968, the almost all-white suburb of Detroit passed a local stop and frisk ordinance, which led to more pressure to do the same in Detroit. For Mayor Cavanagh as well, the political equation shifted toward doing whatever it took to curb crime and disorder.

After the Dearborn law, support for stop and frisk increased on Detroit's Common Council, despite strong opposition from African American members. Police Commissioner Ray Girardin also expressed hesitation and stated that Detroit should await the pending Supreme Court decision in Terry v. Ohio before acting.

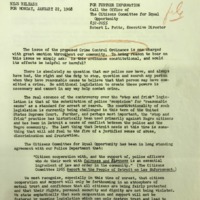

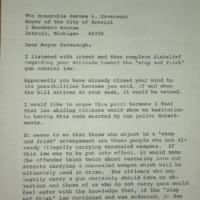

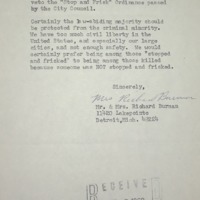

In January 1968, the Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity issued a press release (right) insisting that a stop and frisk law would exacerbate the rift between the African American community and the DPD. The CCEO argued that police officers should only stop and search a citizen with probable cause, not mere "suspicion," and pointed out that "the 'stop and frisk' practice has primarily been used against Negro citizens and has been in Detroit a cause of conflict between the police and the Negro community." African American clergy in Detroit also continued to speak out against a stop and frisk law.

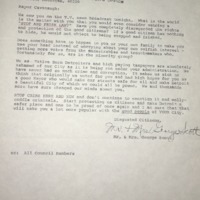

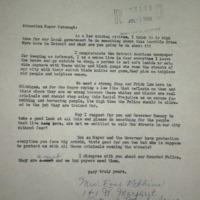

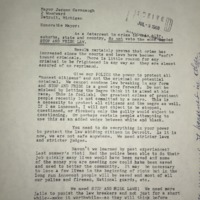

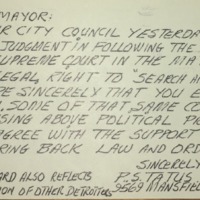

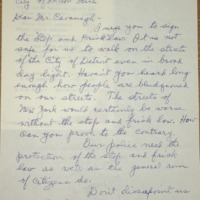

Letters from White Residents

Mayor Cavanagh received an avalanche of letters from Detroit residents, mostly white people, expressing strong support for stop and frisk and drawing a distinction between the criminals and the "good people," with the police on the side of the latter. White citizens who demanded stop and frisk, of course, did not live in the black neighborhoods that police targeted and generally appeared unable to understand the civil rights position that the policy infringed on the rights of "law-abiding" black citizens.

The events of July 1967 and the white backlash against Black Detroit virtually guaranteed the stop and frisk law's passage. Supporters, as in the above letters, claimed that innocent, law-abiding citizens had nothing to fear and that stop and frisk would bring comfort to communities plagued by crime. While support from the public influenced Detroit's passage of a stop and frisk law, nothing was more influential than the Supreme Court's Terry v. Ohio decision in June 1968. The ruling neutralized opposing arguments that the law would be unconstitutional and ushered in a wave of support from many elected officials and a large part of the general public alike. The Common Council voted 5-to-2 in favor of a formal stop and frisk law on July 2, less than a month after the historic Supreme Court decision. African American councilman Nicholas Hood and progressive white councilman Mel Ravitz were the only opponenrs. One week later, Mayor Cavanagh signed the bill he had first proposed in November 1965.

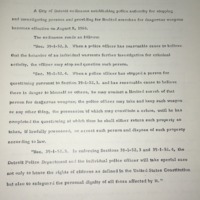

Stop and Frisk Guidelines

In August 1968, the City of Detroit released the "Guidelines for Police Personnel Functioning in Public Spaces and Investigating Criminal Activity." The guidelines established parameters for officers to adhere to under the legalization of stop and frisk, based on these ten points:

- Stopping and searching can cause people to be resentful and should thus be taken seriously by the officer.

- Officers don't need probable cause to search someone but must have reasonable suspicion.

- Hunches cannot constitute reasonable suspicion.

- "The officer must be engaged in legitimate investigation."

- Stops and searches can only be conducted in public places.

- Officers still need probable cause to arrest people, despite only needing reasonable suspicion to search citizens.

- Blanket searches of a given area are not permissible.

- Officers are only allowed to pat down citizens they suspect of criminal behavior. Further searches are allowed only if a pat-down reveals anything illegal.

- If an officer finds anything illegal in the course of a search, then the officer is to take proper legal action.

- Officers must log their searches with the department.

The city of Detroit established these parameters to limit the abuse of stop and frisk, and they sound good on paper. But as history would show, the stop and frisk policy expanded discretionary police powers and oversight, placed minority citizens in a subservient position, led to widespread racial profiling and harassment of innocent people, and represented a major setback for the civil rights movement.

The passage of stop and frisk showed the growing schism between white liberals, as represented by the Cavanagh administration, and civil rights leaders in Detroit. Public opinion was also deeply divided along racial lines as well. A city survey found that 80% of white residents favored the stop and frisk law, while only 35% of African Americans agreed and 55% were opposed.

Sources:

Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan

Jerome Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Michigan Chronicle

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967. 2007.

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City. 2017.