IV. Police Violence and Black Power, 1968-1970

Racial Polarization

The Uprising of July 1967 dramatically ruptured Detroit's reputation as a "Model City" for racial progress—exposing to the entire world the deep-seated tensions caused by decades of racial discrimination and police violence against African American residents. The Kerner Commission labeled "white racism" the underlying cause of racial unrest in Detroit and other American cities, and multiple investigations found that African Americans, especially black youth in the poorest neighborhoods, overwhelmingly considered police brutality to be their foremost grievance against white authority. In the aftermath, mainstream civil rights organizations demanded, and liberal white politicians promised, major reforms to address racial inequality in housing, schools, employment, law enforcement, and other areas. Ominously, the Detroit Police Department believed that it had performed "magnificently" in repressing the 'criminal riot' of July 1967 with extreme violence and denied that police brutality even existed, except as a hoax manufactured by black radicals in their campaign against law enforcement. Detroit's ostensibly still liberal mayor, Jerome Cavanagh, made the parallel claim that "'police brutality' is a thing of the past" in the spring of 1968, when signing a repressive and racially targeted stop-and-frisk law demanded by Detroit's white population, an indication of the full alignment of white liberalism with police repression in the aftermath of the nationwide wave of urban uprisings.

The biracial New Detroit Committee pledged to rebuild the city based on the principle of equal opportunity and proposed to reform the police department under the philosophy of "Law and Justice"--by waging a "major assault" on crime and youth delinquency while ensuring that the police did not discriminate based on race in their enforcement of law and order. Traditional civil rights groups, especially the business-oriented Detroit Urban League, endorsed this agenda of color-blind policing and called on black residents to work with the DPD to fight crime and improve police-community relations. Black power organizations argued that this was impossible because the Detroit Police Department was an inherently racist organization designed to control the black community and protect the segregationist white majority. These black militant and black nationalist organizations demanded full self-determination for black communities and gained significant influence in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the city of Detroit. Their radical analysis, that the systemic racial violence of the Detroit Police Department was politically motivated and not related to crime control, also became central to the critiques leveled by the city's leading African American politicians, including U.S. Rep. John Conyers and State Senator Coleman Young, and by an influential coalition of white leftists who organized the Ad Hoc Action Group in 1968 to protest police violence. All of these organizations demanded the assertion of civilian control over the DPD and called for an elected civilian review board to investigate police brutality and administer discipline, which was adamantly opposed by police officials, Mayor Cavanagh's administration, and most white residents.

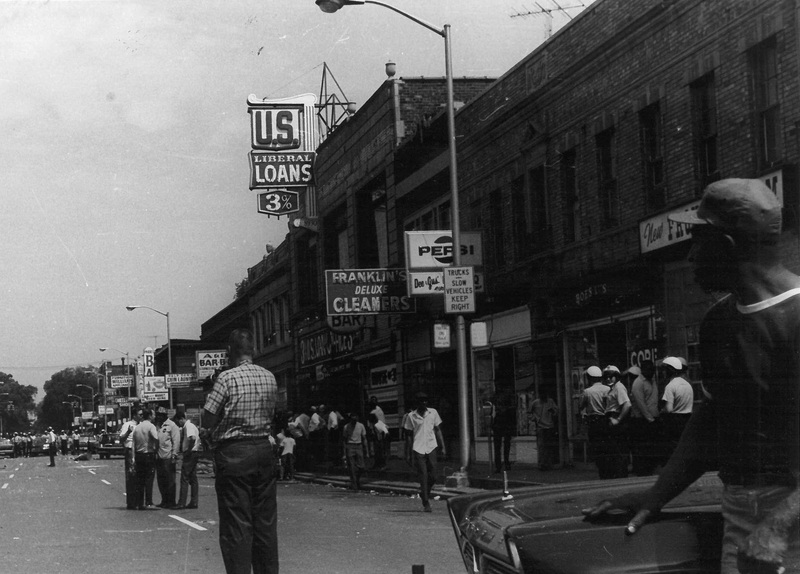

The late 1960s ushered in a sustained period of intense racial conflict in Detroit, a struggle for control that turned much of the city into what the historian Heather Ann Thompson labeled "virtual war zones," as white conservatives and right wing-organizations, led by the Detroit Police Department and the Detroit Police Officers Association union, squared off against civil rights and black power groups and their leftist white allies. The liberal Cavanagh administration was not just caught in the middle but increasingly on the side of active anti-black repression, escalating the campaign to militarize policing in poor black neighborhoods, defending the DPD against almost every complaint of brutality and misconduct, and endorsing the stop-and-frisk law enacted in 1968 to formalize the discretionary authority of individual police officers in the crackdown on black communities. The Tactical Mobile Unit frequently conducted mass street sweeps in African American neighborhoods, as in the photograph at right, for the stated purpose of "riot prevention" but also as a political demonstration of police power and racial control. The racial violence of the overwhelmingly white DPD accelerated in the late 1960s as white flight and demographic transition brought the city to the brink of a black majority, and police officers persistently harassed and often violently attacked black youth in racially transitional neighborhoods and in newly integrated public schools.

It is important to emphasize that the Detroit Police Department did a terrible job at preventing and solving actual crimes against civilians during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The DPD's focus on political repression and racial profiling through stop-and-frisk tactics resulted in many arrests and rampant brutality and harassment of black citizens, but disproportionately few convictions except for low-level traffic offenses. A May 1970 investigation by the Committee on Public Awareness, a group of academic experts at Wayne State University, found that the Detroit Police Department was "not preventing nor prosecuting felony and misdemeanor crimes which would make Detroit safer" (excerpt at right). The so-called Loukopoulos Report, named after its lead author, used the DPD's own data to show that the clearance rate for all major felony crimes, from homicide and rape to burglary and robbery, had declined significantly during the 1960s and that the police department often manipulated crime data to further its political agenda. The report specifically labeled the Tactical Mobile Unit a "fiasco," more committed to racial profiling and political repression than to crime control, with many of its arrests dismissed and most prosecutions involving minor traffic violations rather than crimes against persons or property. Despite multiple recent studies that produced long lists of reforms, the DPD's leadership "has consistently refused to adopt any significant recommendations for institutional and operational improvement."

Politically Motivated Police Violence

This section covers the period from 1968-1970, starting with the enhanced militarization of the police department after the 1967 Uprising and the intensification of its polices of racial profiling and indiscriminate stopping and frisking of black civilians on the streets and in their cars. The DPD, and the increasingly powerful Detroit Police Officers Association union, dismissed and stonewalled almost all allegations of police brutality and miscoduct during this era. The number of civilians killed by the police doubled, the percentage of young unarmed black teenagers killed in police shootings skyrocketed, and the Wayne County prosecutor continued to rule all police homicides as justified no matter what actually happened. The Detroit Police Department also engaged in extraordinary violence against teenagers in a number of high-profile incidents featured in depth, including beatings of civil rights protesters in public schools, a drunken off-duty attack on black youth during a downtown social event, and a militarized assault on countercultural white youth in a public park. Contingents of DPD officers further committed deliberate, politically motivated violence against nonviolent activists, black and white, in two highly publicized 1968 incidents at Cobo Hall as well as conducting harassment campaigns and armed assaults against black radicals in the New Bethel Incident and during a yearlong police-provoked confrontation with the Black Panther Party. In almost all of these incidents and campaigns of brutality and violence, police officers were implementing DPD order-maintenance policy, not operating outside of its boundaries, as they violated the constitutional rights and civil liberties of African American residents and black and white political activists in the city of Detroit.

The map below previews the major incidents of politically motivated police violence against large groups of black political activists and black youth, and in two cases white political activists and white youth, that are all examined in depth in subsequent pages in this section. The map locates these incidents in Detroit's racial geography based on the 1970 census (dark blue = all-black neighborhoods; dark green = all-white neighborhoods).

- Red dots = Police violence against black students engaged in civil rights protests in schools (note how most are in recently desegregated schools in majority white or racially transitional areas)

- Purple dots = Police violence against nonviolent activists in two downtown incidents outside Cobo Hall

- Brown dots = Police violence against and criminalization of groups of black and white youth in social settings (dances, clubs, public parks)

- Black dots = Police repression, armed confrontations, and mass arrests of members of black power/black nationalist organizations

Major Incidents of Politically Motivated Police Violence, 1968-1970

Black Power and White Fear

By 1968, the memories of Mayor Jerome Cavanagh's original pledge to reform the Detroit Police Department and curb its abuses against African Americans, which was critical to bringing him to power with overwhelming black support in the 1961 election, seemed like a lost promise from a completely different era of history. As Cavanagh entered his final two years in office, in a city shaken and polarized by a military occupation and some of the worst urban racial violence in modern American history, the white liberal commitment to "law and order, with justice," seemed like a cross between a broken promise and a naive fantasy.

Mainstream black organizations were losing faith in the Cavanagh administration and its get-tough law enforcement philosophy, especially after the mayor supported a stop-and-frisk law to appease a dwindling white majority in the outlying working-class neighborhoods that had never trusted him in the first place and considered him too supportive of civil rights. Black power groups had denounced Cavanagh's liberal politics as a racist facade for years, and an increasing number of white progressives also turned on him after the 1967 Uprising because of his failure and/or refusal to transform the DPD.

On March 7, 1968, in this polarized racial climate of white fear and growing black power, Cavanagh delivered a televised address aimed at the white and black residents of the city of Detroit and its suburbs. He lamented the "destructive riot" of the previous summer and warned that both right-wing and left-wing extremists were trying to take advantage of the situation to further divide "our community," the already deeply polarized population of metropolitan Detroit. Cavanagh condemned the "voices of violence" on the right and on the left--equating a fringe right-wing anticommunist organization with the city's multiple black power and community control organizations that advocated self-defense and not violence--and pledged that the Detroit Police Department had the power and the will to stop them. The mayor detailed the improvements being made to the DPD, including militarized riot control training, better technology, and enhanced police-civilian coordination to prevent crime. Cavanagh ended by promising that the DPD would "apply the law equally and fairly," while also assuring--and threatening--residents that the police would unleash "the full effect of the forces law and order" whenever necessary. Cavanagh did not, of course, address the critics who argued that the Detroit Police Department's own policies escalated rather than prevented violence in the city's black neighborhoods.

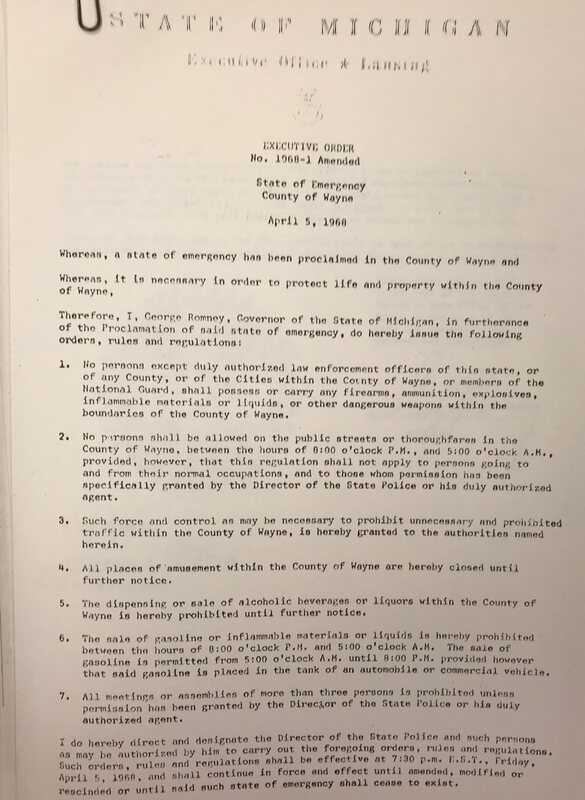

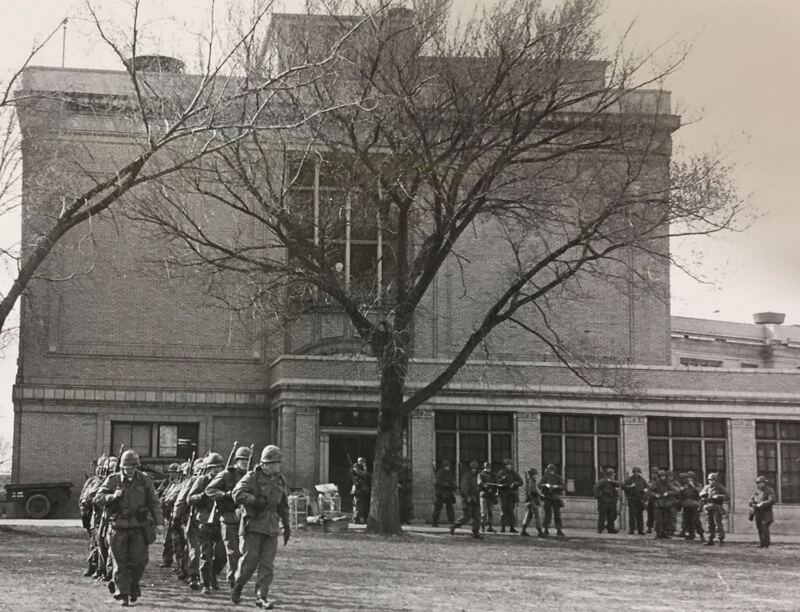

Less than a month later, on April 4, 1968, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., set off a wave of racial uprisings and civil unrest in more than 100 American cities. The white leadership of Michigan feared the worst in Detroit, and Governor George Romney preemptively declared a state of emergency for all of Wayne County and mobilized the National Guard in a deterrent show of state authority. The declaration imposed an 8:00 p.m. curfew, banned all sale of alcohol, and prohibited "meetings or assemblies" of more than three people. The Michigan National Guard deployed and staged at several Detroit high schools (see photographs below) but in the end was not required to reoccupy the city as it had in July 1967.

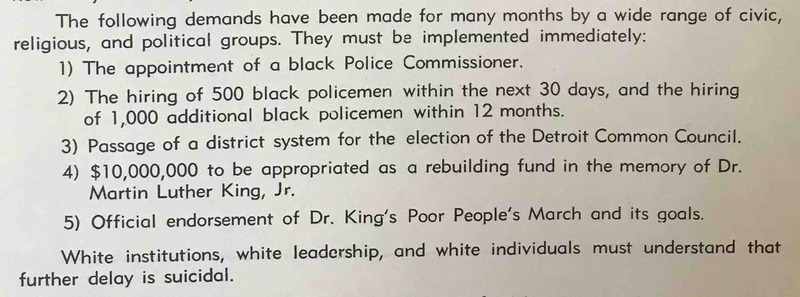

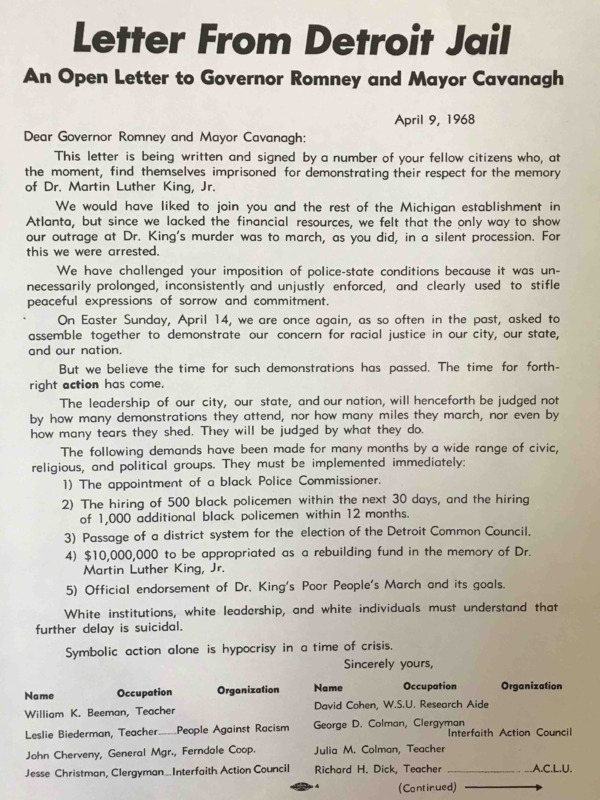

Detroit did not experience serious racial violence during the national unrest of April 1968, perhaps because of this preemptive display of state power, or the lingering fatigue from the Uprising nine months earlier, or a combination of other reasons as well. The Detroit Police Department did conduct a series of "riot prevention" street sweeps in African American neighborhoods, with significant force and brutality. The police also arrested nonviolent political activists who organized protests in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr., under the authority of the governor's state of emergency declaration. A biracial group of eight of them responded with the "Letter from Detroit Jail" (below right), denouncing the "imposition of police-state conditions . . . unjustly enforced and clearly used to stifle peaceful expressions." The "Letter from Detroit Jail" called for the appointment of an African American police commissioner and a crash program to change the racial makeup of the Detroit Police Department, which at the time was 94% white in a city that had become more than 40% African American. Black power organizations and other civil rights activists went even further, demanding radical changes to bring about civilian control of the DPD.

View documents and images from the April 1968 state of emergency in Detroit in the gallery below.

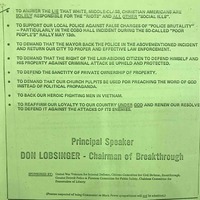

The urban racial unrest of summer 1967 and spring 1968, locally and nationwide, created an explosive situation in the city and suburbs of Detroit. In Cavanagh's March 1968 speech promising to maintain law and order, the mayor announced the establishment of a Rumor Control Center with a 24-hour hotline run by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR). The main priority was to suppress the conditions for another racial disturbance, in recognition that the Kerner Commission's report released that same month had emphasized the role of unfounded rumors in inflaming racial tensions. The Cavanagh administration was also very worried about the spike in gun sales, especially in white neighborhoods in the city and throughout the white suburbs, but also among African American residents who feared the police and the rise of right-wing vigilante groups such as Breakthrough, a far-right anticommunist movement based in Detroit's white working-class neighborhoods. Breakthrough held mass meetings to defend the police department against brutality charges, attacked the Cavanagh administration for not shooting more black rioters in July 1967, and called for "the law-abiding citizen" to bear arms in self-defense against violent criminals and black militants.

The Rumor Control Center received more than 10,000 calls in the first two months of operation in the spring of 1968, and the volume skyrocketed after fears of another riot/uprising intensified following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. In a typical pattern, civil rights protests such as black student school walkouts would prompt a flood of calls from fearful white residents, and then the ensuing police crackdowns (which generally included serious brutality) would elicit alarmed calls from black residents who heard rumors that the police were shooting African American youth.

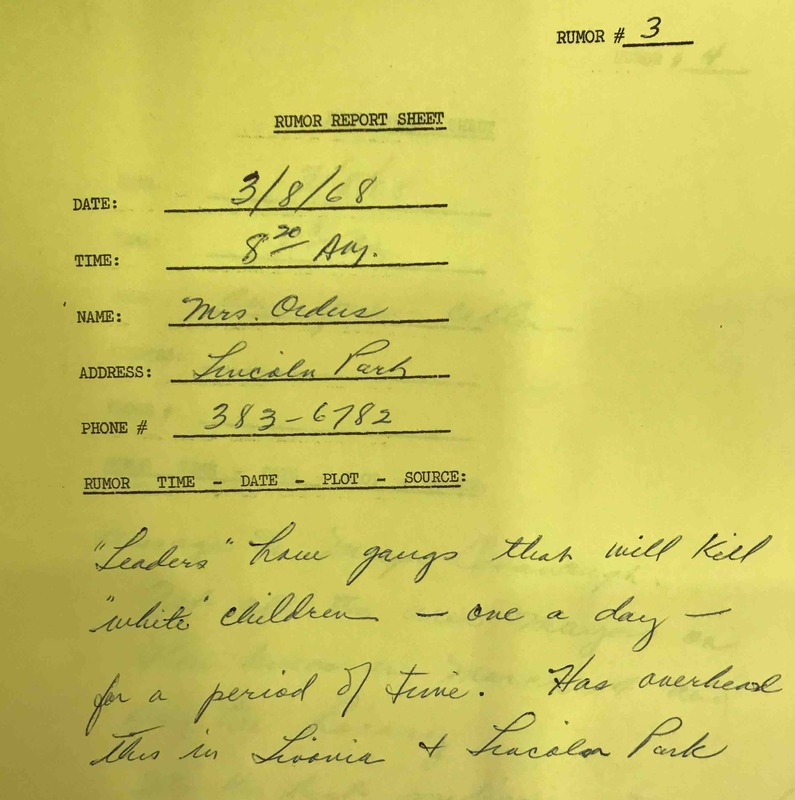

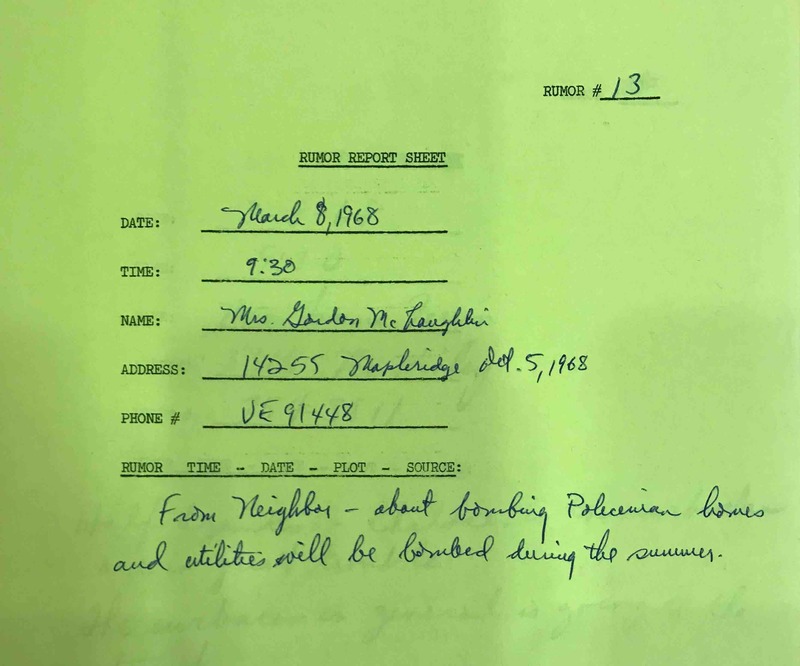

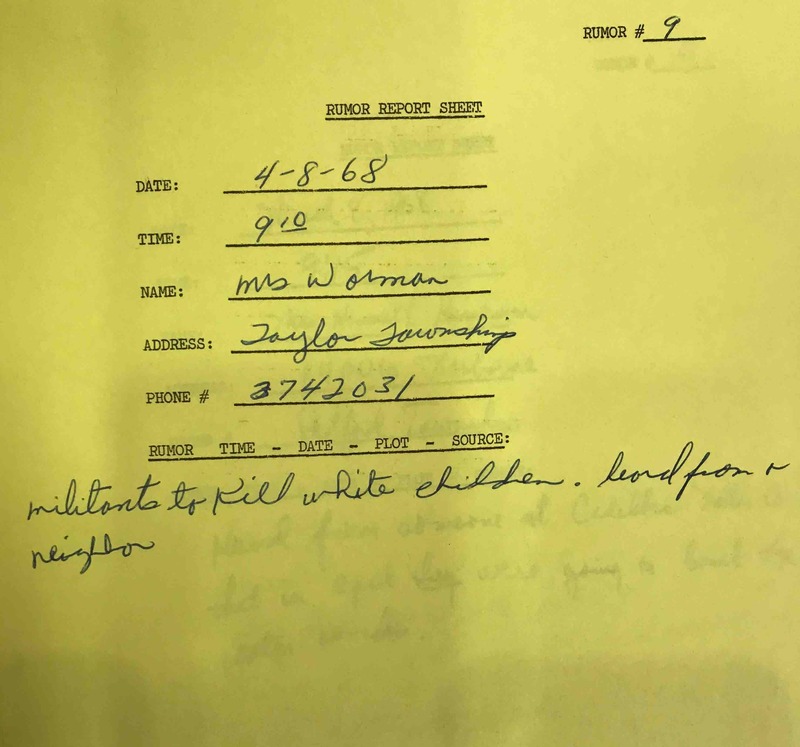

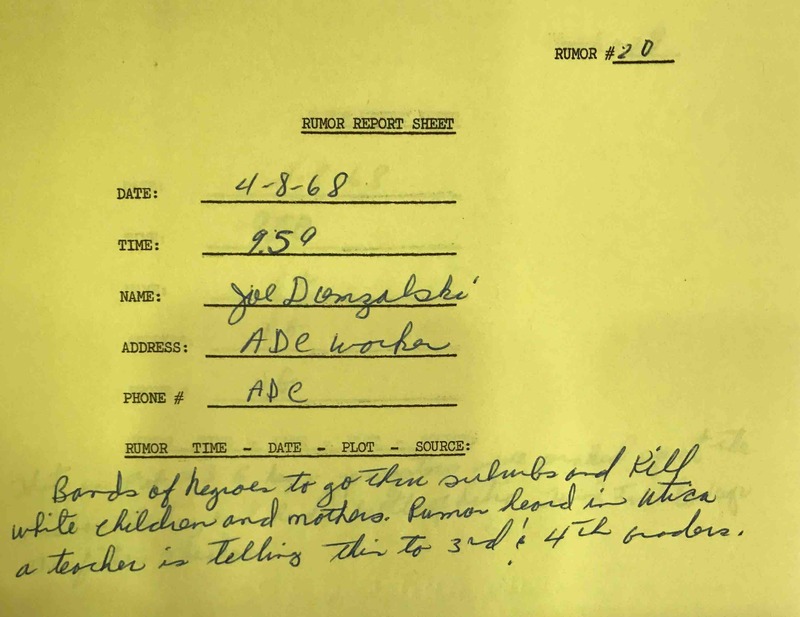

The Rumor Control Center sought to defuse the racial polarization in the city and suburbs of Detroit during and after the spring of 1968, but its records also confirm the wild fears and anxieties of many white residents of the metropolitan region. Many of the calls came from the same white working-class neighborhoods where white police officers also lived, and a number cited police officers that the caller knew as the source of the information. Hundreds of rumor reports in the archives are almost identically worded variations on the theme that black power militants were planning to invade white neighborhoods in the city and its suburbs to either kill white children or conduct targeted assassinations of white policemen. (To be clear, there was zero evidence for these white fear/fantasy rumors). The sampling of rumor call records below, from March and April of 1968, includes the following claims and fears about the imagined plotting of black power militants:

- "''Leaders have gangs that will kill white children--one a day--for a period of time."

- "Bombing policeman homes and utilities will be bombed during the summer."

- "Militants to kill white children."

- "Bands of Negroes to go through suburbs and kill white children and mothers."

The DPD's campaign of repression against black radicals during the late 1960s and early 1970s revolved around related and equally distorted views that black power groups that called for community self-determination and insisted on the right of self-defense against police brutality were in actuality plotting violent attacks on law enforcement. During this polarized era, the DPD also responded with significant violence against politically active youth and nonviolent political activists, especially those that protested police brutality, revealing that the police department criminalized civil rights and black power activism with broad strokes and operated as an independent and often lawless political organization itself. In an already racially polarized era, the level of police violence and police criminality in the city of Detroit made an already bad situation much, much worse.

Sources

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Police Harassment Investigation, Feb. 19, 1968, Box 26, Folder 6, Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

Riots and Protests, Detroit 1967, General Photographs Collection, Michigan State Archive

Detroit Commissions on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

Loukas Loukopoulos, The Detroit Police Department: A Research Report (Detroit: Committee on Public Awareness, May 1970)