12th Street Blind Pig

A Variety of Root Causes

The Detroit Uprising began with a police raid on a blind pig on 12th Street near Clairmount, an African American neighborhood on the West Side of Detroit.

"Blind pigs" were unlicensed, and therefore illegal, after-hours drinking establishments that had existed in Detroit since the early 20th century. They provided alcohol to middle-class African Americans during the era of Prohibition, often through pay-offs to the police. After the repeal of Prohibition, blind pigs continued to flourish and provided an alternative to white-owned bars in a racially segregated city. According to Hubert Locke, an African American civic leader who advised the Detroit Police Department in 1967, blind pigs also became places for prostitution, sale of narcotics, and other illicit and illegal activities. In fact, some black residents of the neighborhood surrounding the 12th Street blind pig had complained about street prostitution in the area and blamed police corruption for allowing the sex market and other so-called "vice" activities to flourish.

Many other black residents deeply resented police harassment for what they considered to be a harmless social gathering, especially after licensed bars closed at 2:00 a.m. In the spring of 1967, a federal civil rights investigator visited Detroit and warned that the police policy of frequent raids on blind pigs was inflaming racial tensions. The investigator's report explained that blind pigs were "an important part of life in Detroit's ghetto" and that, while some local residents might support a police crackdown, many others were alienated by the heavy-handed tactics. Police raids, in this account, were "an unwise attempt by a white middle class to foist its morals on the lower class."

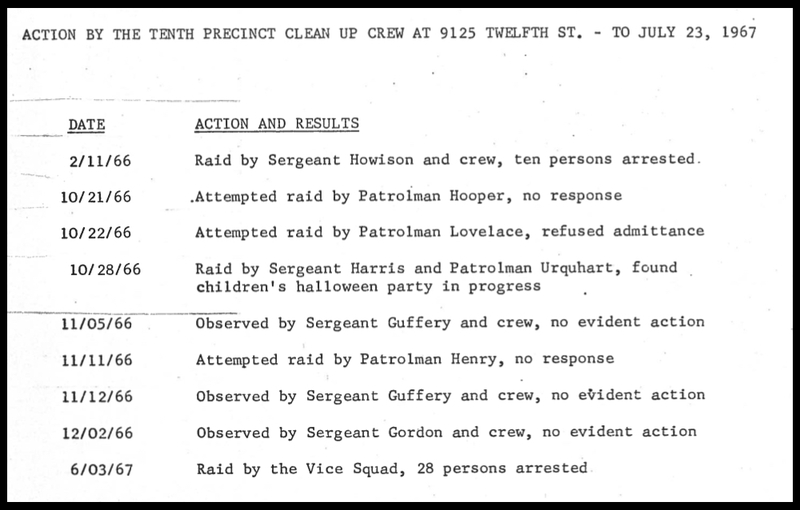

The DPD's vice squad for the 10th precinct had raided, or attempted to raid, the blind pig at 9125 12th Street at least nine times since February 1966 (below), before the fateful mass arrests in the early morning hours of July 23, 1967. Two vice raids had resulted in multiple arrests, of 10 and 28 people, while another had found a Halloween party for local children in progress. This is an indication that blind pigs served a range of purposes in the working-class black neighborhoods of Detroit. Since 1964, the building that contained the Economy Printing Co. also housed the United Community League for Civic Action, which was both a front for the blind pig and a local political organization whose leaders considered a speakeasy to be a good way to make money at their multifaceted community center. The real story is possibly even more complicated. Some local residents, including one of the blind pig's proprietors, claimed later that the vice squad only raided the establishment when they were late with, or refused to continue to make, payoffs to the police to remain open.

The July 23 Raid

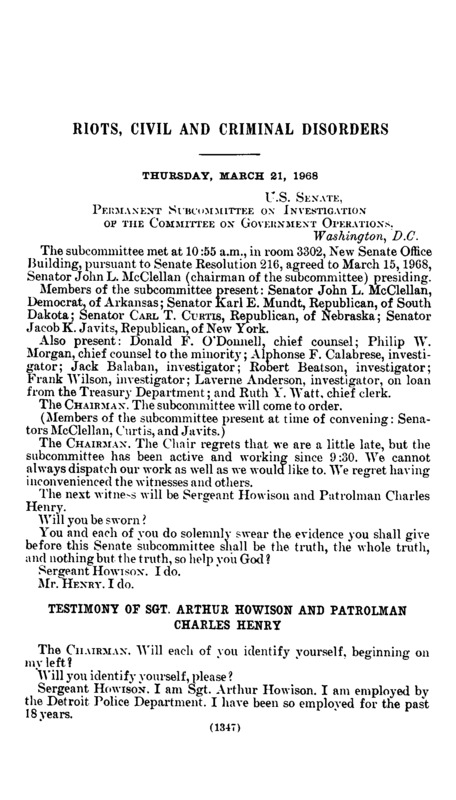

In the early morning hours of Sunday, July 23, the 12th Street blind pig was hosting a party for three African American servicemen who had just returned from Vietnam. Sometime around 3:45 a.m., an undercover vice squad officer named Charles Henry gained entrance. The plainclothes officer was, by necessity, African American, like everyone else inside the building. He proceeded to buy a beer at the bar. A few minutes after that, the vice squad crew led by Sgt. Arthur Howison broke down the door and raided the establishment. There were at least 85 people inside, far more than the police had anticipated. Howison made the call to arrest them all.

Eight months later, Sgt. Howison and Patrolman Henry testified to the U.S. Congress about what happened that evening (gallery, below left). They explained their mission to stop the "illegal sale of liquor," and also gambling. After they busted in, the four-man crew had to arrest far more people than they had expected, which was chaotic. They called for paddy wagons to transport the prisoners, and loading them took about 45 minutes.

As the loading took place, according to Patrolman Charles Henry, a crowd of around 200 people gathered and a black man began shouting: "Are we going to let these white coppers take these people away? Why do they come down here and do this in our neighborhood?" (This man later faced charges of inciting to riot). Under questioning from right-wing congressmen, who were investigating an alleged black power conspiracy to incite "criminal disorders," Patrolman Henry made it clear that he believed the crowd reaction to the blind pig raid was "spontaneous," rather than planned.

Sgt. Howison, a white officer, told the congressional hearing that people in the crowd "were hollering about the white police coming down and harassing them, why didn't they go to Grosse Pointe [a wealthy white suburb] and raid the houses over there, instead of bothering people down here."

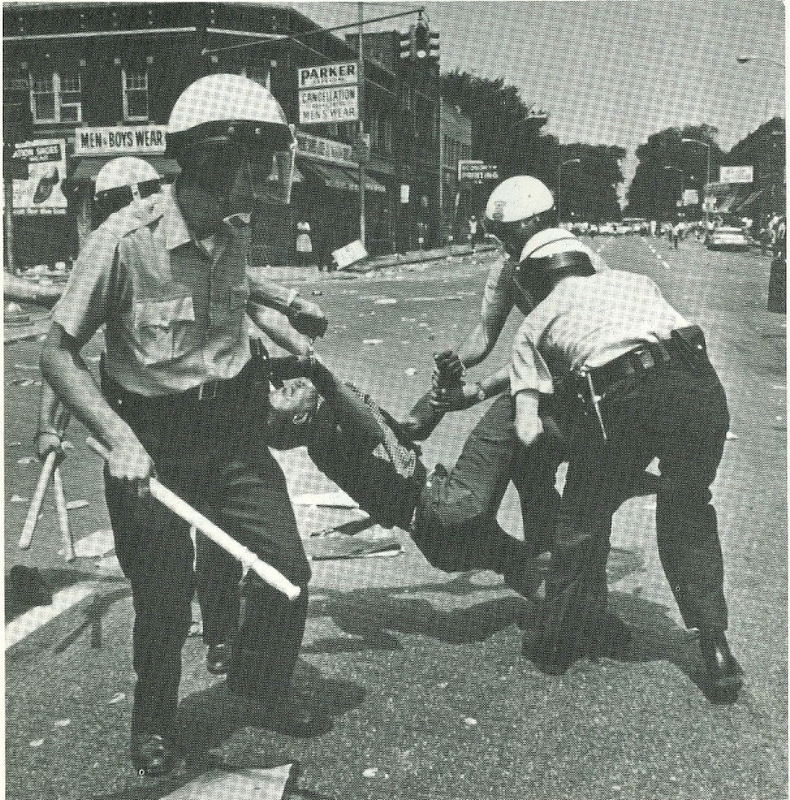

Around 5:00 a.m., someone threw a bottle at a patrol car, and a few others in the crowd began to break windows in storefronts. By 8:00 a.m., the crowd had increased to several thousand people, and to around 9,000 an hour later. The police had lost control of the situation at 12th and Clairmount, and the Detroit Uprising had begun.

From "Routine Procedure" to "Catalytic Event"

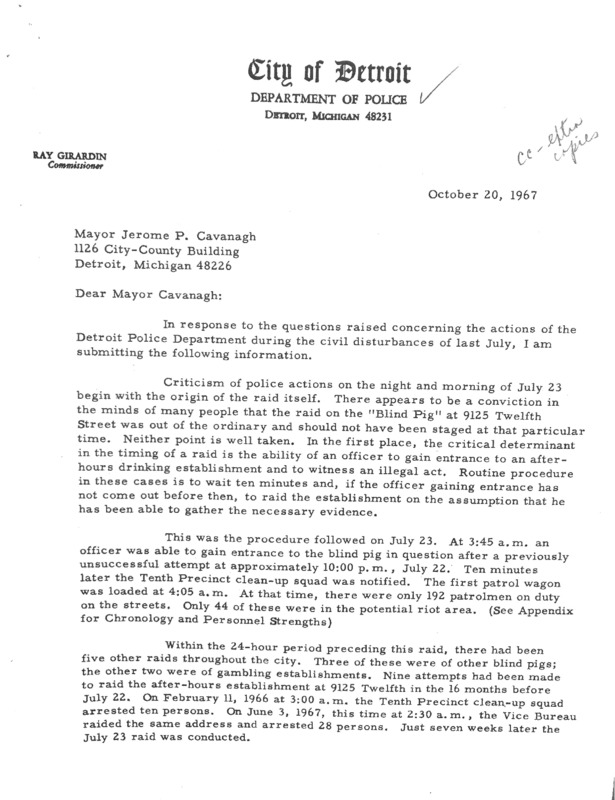

The police raid on the 12th Street blind pig was a "routine procedure" and "not out of the ordinary," DPD Commissioner Ray Girardin emphasized in an assessment provided to Mayor Jerome Cavanagh in October 1967 (see gallery below). His report noted that the DPD had conducted five other raids in other parts of the city in the previous 24 hours, three of blind pigs and two of gambling establishments. The police commissioner did not consider the incident that sparked at least 43 deaths, six days of civil unrest, and more than 7,000 arrests to be an incident of police harassment of African Americans in Detroit or anything more. He contended that everything would have been fine if the unknown person had not thrown the bottle at the police car.

Commissioner Girardin also defended how quickly the DPD mobilized, especially through its Tactical Mobile Unit, and said the crowd "appeared to be controllable" for the first few hours. In his report (fourth page), Girardin specifically blamed the failure of black community leaders to convince the crowd to disperse, calling this the moment when "the attitude of the people on the streets began to change."

Girardin, notably, also defended DPD officers from criticism for not stopping the "riot" in its tracks by shooting or tear-gassing people in the crowd on the morning of July 23. The commissioner noted that many women and children were present, and he also said that in no other previous incident of rioting in an American city "have the police gone into the area and begun shooting immediately."

On July 24, the day after the raid on the blind pig, the hesitation of DPD officers to shoot "rioters" and "looters" changed decisively.

The gallery below contains the congressional testimony of two officers from the vice squad, Commissioner Girardin's October 1967 report to the mayor, and two sections from a December 1967 investigation by staff members of the Cavanagh administration, "The Detroit Police Department and the Detroit Civil Disorder," detailing "The Catalytic Event": the blind pig raid and its immediate aftermath.

Sources

Ray Girardin Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Image Gallery, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

“Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders: Part 6,” Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Senate,” March 21-22, 1968 (Washington: GPO, 1968)

Detroit Urban League, “The People Beyond 12th Street: A Survey of Attitudes of Detroit Negroes after the Riot of 1967,” 1967, Box 1, Joseph L. Hudson Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2007)

Hubert G. Locke, The Detroit Riot of 1967 (1969, reissued 2017)