New Bethel Incident

On March 29, 1969, around a dozen armed officers from the Detroit Police Department invaded the New Bethel Baptist Church and arrested 142 African Americans gathered for the national convention of the Republic of New Africa (RNA), a black nationalist organization that had been infiltrated by the FBI and was also under surveillance by the Michigan State Police and DPD Intelligence Bureau. The New Bethel Incident began when two white police officers initiated a confrontation with one or more armed RNA bodyguards outside of the church, which was located on the West Side of Detroit in the heart of the African American community. The surviving officer said they were just talking to the armed African American men and did not have their guns drawn, which civil rights and black power groups widely disbelieved.

Although what happened next is in dispute, shots were exchanged and resulted in the death of one officer and the wounding of the other. When DPD back-up arrived, the police contingent entered the church firing their rifles, shot two unarmed people in cold blood and at least two others, threatened to kill many more of their prisoners, and committed "physical brutality in considerable amounts," according to the investigation of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (right). The DPD's official report claimed that "a hail of gunfire" from inside the church preceded the armed invasion by its officers, which was a lie to justify the abuses that happened inside and was contradicted by all physical evidence.

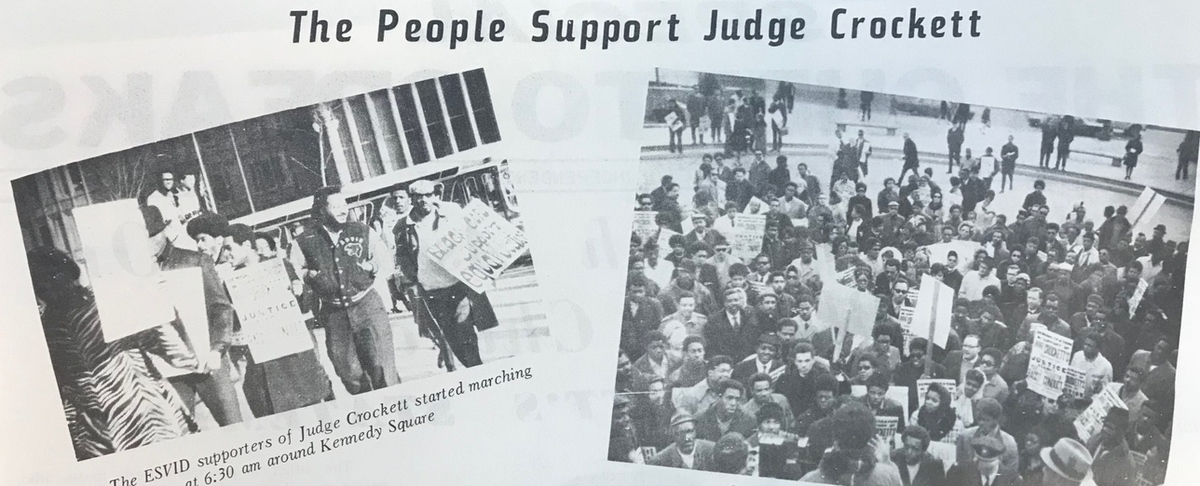

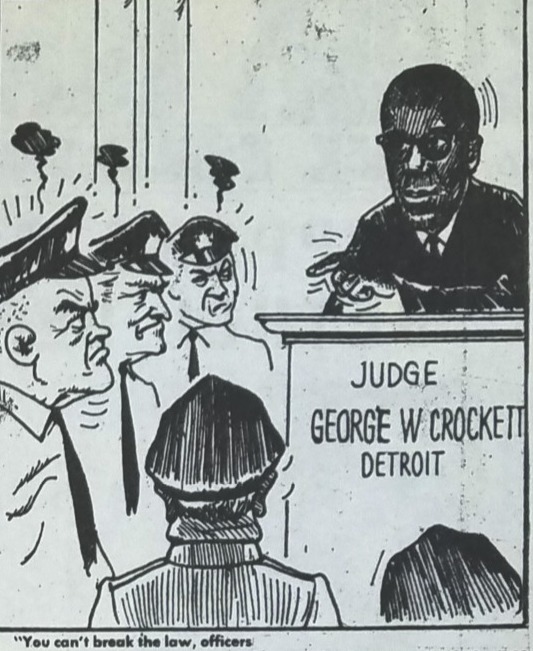

After the mass arrest of all 142 African Americans present, for "conspiracy to commit murder," Judge George Crockett of the Recorder's Court strongly criticized the police action and ordered the release of everyone who had been inside the church and wrongfully detained without any evidence of criminal activity. Law enforcement officials and the DPOA union then launched a sustained campaign against the African American judge, while Detroit's coalition of radical organizations mobilized to defend Crockett and his insistence on protecting the constitutional rights of black citizens and guaranteeing equal justice under the law. The New Bethel Incident resulted in two murder trials of members of the Republic of New Africa, who were defended by the radical African American attorney Kenneth Cockrel. The DCCR investigation and the evidence that emerged during the New Bethel trials highlighted the illegal and repressive actions of the Detroit Police Department and resulted in the acquital of all defendants, without fully resolving the debate over what really happened both inside and especially outside the church.

Republic of New Africa and FBI Surveillance

The Republic of New Africa originated in Detroit at the Black Government Conference called by the Malcolm X Society in late March 1968, almost exactly one year before the New Bethel Incident. The founding meeting occurred at the Central United Church of Christ, also known as Shrine of the Black Madonna, pastored by Rev. Albert Cleage, one of the city's most influential black power leaders. About two hundred African American delegates from across the nation signed the RNA’s declaration of independence to be "forever free and independent of the Jurisdiction of the United States." The RNA's purpose was to establish a "Black Nation" inside the U.S. and to gain international recognition as a politically independent entity. The Black Nation would be situated primarily in the South, obtaining Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. The RNA demanded that the U.S. government pay each African American $10,000 as reparations for slavery in addition to ceding this territory and turning over control of the "black ghettoes" to the people who lived there. The RNA delegates elected Robert F. Williams, a Black Power leader from North Carolina currently in exile in Cuba, as their president, and as vice-president Milton Henry, a well-known black nationalist attorney in the Detroit area who had gained prominence in 1963 as a leader of the protest against the police murder of Cynthia Scott.

The RNA's founding document stated that "we have never been citizens of the United States" because the government had never and would never extend constitutional protections to black people. The RNA asserted the right of black people in the South and in the ghettoes of the North to self-determination, through a plebiscite if possible and "by arms if necessary."

The Federal Bureau of Investigation immediately placed the Republic of New Africa under surveillance as part of its illegal COINTELPRO campaign to "disrupt" and "neutralize" what it called "Black Nationalist-Hate Groups." While the ostensible purpose of this COINTELPRO was to "counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder," the FBI infiltrated a broad spectrum of black power and black nationalist organizations with undercover informants who often fomented disorder and espoused violence in circular justification of the government's repression campaign. The FBI's first COINTELPRO memo on the Republic of New Africa (right), dated two days after the group's founding, was provided by a redacted source who was almost certainly an undercover agent present at the Detroit conference. The source stated that delegates at the RNA's founding convention had "called for guerilla warfare against the United States" and devised plans to provide black Americans with military training in foreign countries. The FBI rapidly infiltrated RNA chapters around the country, and the full COINTELPRO file makes clear that the Bureau had more than a dozen and perhaps several dozen informants inside the organization, making up a significant percentage of its active membership. It is very likely, based on the general COINTELPRO tactics, that these spies were some of the most vocal advocates of violence as part of the FBI's broader political strategy to discredit the black power movement.

The FBI sent several undercover informants to the second convention of the RNA, held in Detroit in late March 1969, that culminated in the New Bethel Incident. Based on the COINTELPRO file, it is almost certain that the FBI also had an undercover operative in a position of influence inside the central group in Detroit. The FBI shared its "counter-intelligence" with the Michigan State Police, which had its own spies inside the RNA, and with the Detroit Police Department's Intelligence Bureau, the political surveillance unit that possibly did as well. The gallery below contains a few of the documents from the FBI's extensive surveillance file on the Republic of New Africa. The documents are full of redactions, including all names of FBI undercover agents and informants. The gallery includes:

- FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's personal authorization of payment for an undercover informant to travel from Los Angeles to Detroit for the RNA's second annual convention in March 1969. This document also contains information about what the FBI expects to happen at the Detroit meeting provided by multiple redacted sources, meaning by undercover informants who had infiltrated other RNA chapters. (The FBI file also includes payment authorization for undercover informants from Cleveland and Dayton, Ohio, among other cities).

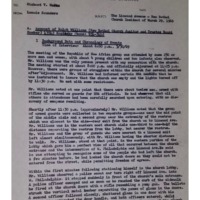

- An urgent teletype, dated 3-31-69, from the Detroit office of the FBI to Director Hoover, reporting the account of an FBI informant inside the RNA convention that a "group of Negro males" outside the New Bethel Church fired on two Detroit police officers, killing one and wounding the other. The source identified three RNA members who did the shooting, but their names are redacted. The source also claimed that these RNA members later shot at the backup police from inside the church, for which there is no evidence, potentially discrediting this source's account. The teletype also lists five redacted names, presumably FBI informants, who were among the people inside the church who were arrested. The Detroit office's informants also stated that the RNA had no plans for violence and that the killing of the officer was a "spontaneous, independent act."

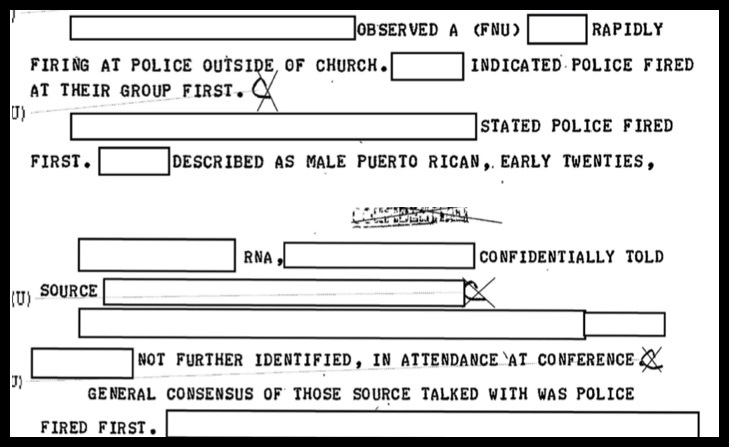

- An urgent teletype, dated 4-1-69, from the Cincinnati office of the FBI to Director Hoover, providing the account of an undercover informant who spoke with multiple RNA members who all said that the "police fired first" in the initial confrontation outside the New Bethel Church. The informant further stated that the backup police fired "dozens of shots" into the church before entering, making this source likely more reliable than the teletype from the Detroit office.

- Director Hoover's report to U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell on the Republic of New Africa, stating that black extremists fired on the first two police officers and then fired on the backup police from inside the church--meaning that Hoover selectively reported the information from sources that cast the RNA as the sole instigator of violence and deliberately silenced the informants who had reported police-instigated gunfire both inside and outside the church.

2. Detroit FBI teletype to Director Hoover on shooting at RNA convention based on informants, 3-31-69 (6 pgs.)

What Happened Outside the Church?

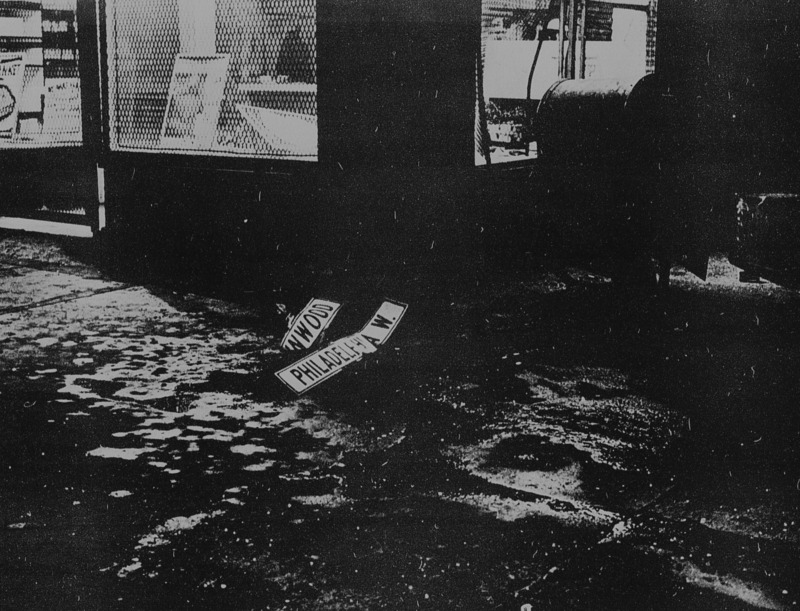

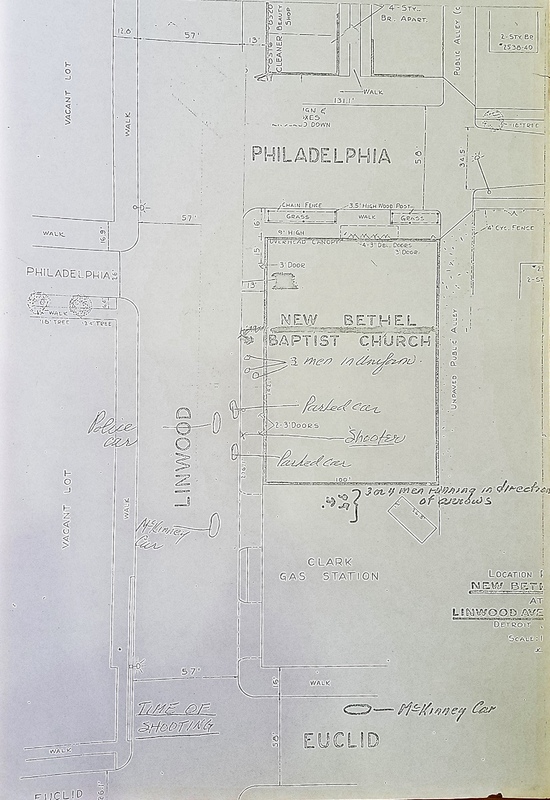

The New Bethel Baptist Church, located at the intersection of Linwood and Philadelphia in West Detroit, was pastored by the Reverent C. L. Franklin, a prominent African American minister and civil rights leader. The Republic of New Africa rented the church for a rally, as part of its multi-day convention. The event inside the New Bethel church took place on the evening of March 29, starting at 8:00 p.m. and ending around 11:30 p.m. In the next few minutes, armed bodyguards escorted the main leaders of the RNA out of the church and into their cars. According to the Detroit Free Press investigation, which relied on police sources, DPD Patrolmen Michael Czapski and Richard Worobec were driving by at this time and radioed in, "approximately 10 to 12 Negro males with guns entering automobiles."

The officers proceeded to get out of their car to investigate the situation, and what they did next is undetermined. People Against Racism, a white New Left organization in Detroit, asked at a protest march if it was in any way believable that two white officers would approach a group of armed black men with "no weapons in their hands." Witnesses said they heard a single shot, and then another, and then a sustained volley of gunfire. This could support the position that one or both of the officers fired a shot at one of the Republic of New Africa bodyguards, who then returned extensive fire. But that is still only in the realm of informed speculation, and no witness testified to this effect.

Around 11:42 p.m., Patrolman Czapaski was dead from up to seven bullet shots and his partner, Patrolman Worobec, was seriously wounded. Worobec got into the squad car to drive away and crashed into a dry cleaners at the intersection of Linwood and Philadelphia. There were also bullet holes in the car, indicating he might have been fired upon while fleeing. Both officers were young white men in their 20s. In an operational sense, it is unclear if the two patrolmen were aware of the significant degree of multi-agency law enforcement surveillance of the Republic of New Africa when they confronted the group of armed African American men outside the New Bethel Church that night. A centrally planned DPD confrontation would likely have involved a larger contingent of officers. It is also, to repeat, not clear who shot first and what exactly happened after the two officers got out of their car.

Government Sources

Police Radio Log. According to the police radio log provided by the DPD to investigators (left), which is only a partial and edited transcript, squad car 10-5 (Czapaski and Worobec) called in at 11:42 p.m. stating "We got guys with rifles out here, Linwood and Euclid." The police dispatcher immediately sent three cars as backup. Then squad car 10-5 (this would have been Patrolman Worobec) radioed in "Help" "Help" "Ow" Ow"--and the dispatcher responded with an "all units officer in trouble" emergency bulletin, followed by a "two officers shot" bulletin and a warning that the suspects were still actively firing.

However, the authenticity and reliability of this police log is questionable, because it further states, based on reports from the backup squad cars, that two additional officers were shot (possibly meaning shot at) from "inside the church" between 11:48 and 11:49 p.m. There is no evidence that this actually happened, although the allegation that black militants fired at the backup police from inside the church was central to the DPD's justification of its officers firing many rounds at the people inside. It is certainly possible to doctor a police radio log print out before turning it over to investigators. (It also seems implausible that two white officers would refer so diplomatically to a group of armed black men standing a street corner as "guys" and would not note their race in the initial radio call). The single page provided to the investigators of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and reproduced here is obviously edited rather than a verbatim transcript, because there is no way that the entire exchange between a radio dispatcher and multiple squad cars between 11:42 p.m. and 12:06 a.m., during a situation when two officers were shot and the DPD invaded a church, could fit on one page.

Michigan State Police Intelligence Bureau. There is no question that multiple law enforcement agencies had the RNA rally at New Bethel under surveillance before the fatal confrontation between the two white police officers and the group of black radicals. In addition to the half-dozen or more informants and undercover agents attending the rally who were working for the FBI, the Michigan State Police (MSP) had an "Intelligence vehicle" outside the church at the time of the shooting and another undercover officer "in the vicinity." The DPD's Intelligence Bureau also had at least two undercover officers on the scene, including one, Patrolman Landeros, who directly witnessed the shooting, according to the confidential intelligence report by the Michigan State Police (right). Landeros was working as a liaison to the Intelligence Bureau of the Michigan State Police, which was its own version of COINTELPRO. The MSP report gets a lot of the details wrong, because it is a minute-by-minute account that the authors kept revising as more information came in, and it also has to be assessed critically as a law enforcment document that might not include known evidence of police culpability. The MSP document, which uses racist language, initially reported that "a large group of negroes" fired on a squad car that was driving by but then amended this to state that the two white officers got out of their car and approached "a group of 12 to 15 colored subjects" who began shooting at them. (It is almost impossible to believe that the police officers did not approach a group of armed black men with their own guns drawn, but the MSP report elides this information). The MSP report tentatively identified the shooters as Alfred Hibbitt (Alfred 2X) of Detroit, Alvin Henderson of New York City, and "Adeolu" (an African name, full identity unknown).

The confidential Michigan State Police document reproduced here raises serious questions about whether the black militants fired first, primarily for this reason: the report identified Patrolman Landeros as a direct eyewitness to the shooting and an undercover operative for the Intelligence Bureau. Yet this DPD officer who witnessed the alleged murder of one police officer and serious wounding of another does not appear in any newspaper coverage of the New Bethel Incident and did not testify to what he saw at either of the trials. It is possible that the MSP and DPD wanted to protect the identity of an undercover officer involved in political surveillance of black militant groups, but it is also possible that what Patrolman Landeros saw outside the church is not what the DPD and the MSP said happened.

FBI Undercover Informants. The reports by the FBI's undercover informants are contradictory, as detailed in the previous section on this page. The undercover source working with the Detroit office stated that three RNA members opened fire on the two officers, but the source also stated that RNA militants kept firing at backup officers from inside the church, for which there is no evidence. It is certainly plausible that the Detroit FBI office, which worked closely with the DPD Intelligence Bureau, would report the DPD's version of the story portraying the white officers as the sole victims to the FBI headquarters in Washington. This makes it particularly intriguing that the undercover informant who worked for the FBI's Cincinnati field office stated that the "general consensus" from everyone present was that the "police fired first." This source's reliability is further strengthened because he did not state that the militants fired at the backup police from inside and instead stated that the police unloaded "dozens of shots" into the church, which definitely happened. The Cincinnati source's account is not airtight because it does not seem that this informant directly witnessed the confrontation with Patrolmen Czapski and Worobec. But he also made clear to his FBI handlers that "at no time was violence planned or discussed at rally."

Patrolman Richard Worobec, who was wounded, later testified that a "lone Negro male" wounded him and killed his partner that night. In an interview with the Homicide Bureau, he said that a group of men with guns were on the street corner but scattered after the two officers got out to investigate. Then "I saw the man wheel and shoot Czapski. I started to reach for my revolver and I was hit in the leg and went down." Worobec made it back to the car, called in the attack, heard a lot of gunfire and decided to flee, and then crashed.

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations, which was highly critical of subsequent police actions inside the church, believed that what happened to Patrolman Czapski "cold blooded murder." DCCR investigators did not think that the two officers were aware of the massive surveillance operation underway and considered their decision to interrogate the armed man outside the church to be proper.

Civilian Sources

Max Hardeman was across the street, heard a shot, and observed a uniformed legionnaire (a RNA bodyguard) "fire several blasts" at a police officer. Like all other witnesses, he did not observe what might have precipitated this encounter. Hardeman also stated that he did not see the person who fired the shots flee into the church. (Hardemann's account is in the DCCR investigation report at the top of this page).

The statements of other civilian witnesses were taken by defense attorneys after the prosecution charged three RNA members with the murder of Patrolman Czapski: Rafael Viera, Clarence Fuller (known as Chaka), and Alfred Hibbit (known as Alfred X).

The cumulative effect of their sworn statements is that they all saw only one man fire at the police officers. They differ in their descriptions of whether this man was lighter-skinned or darker-skinned and how tall he was. The witnesses were also all either emerging from the church or driving by and were unable to testify to what the police officers might or might not have done in the initial confrontation, before the lone man fired at them. They further confirm that multiple police officers in addition to Patrolmen Czapski and Worobec were already on the scene and responded immediately--rather than the DPD's claim that this only happened after the dispatcher called for backup.

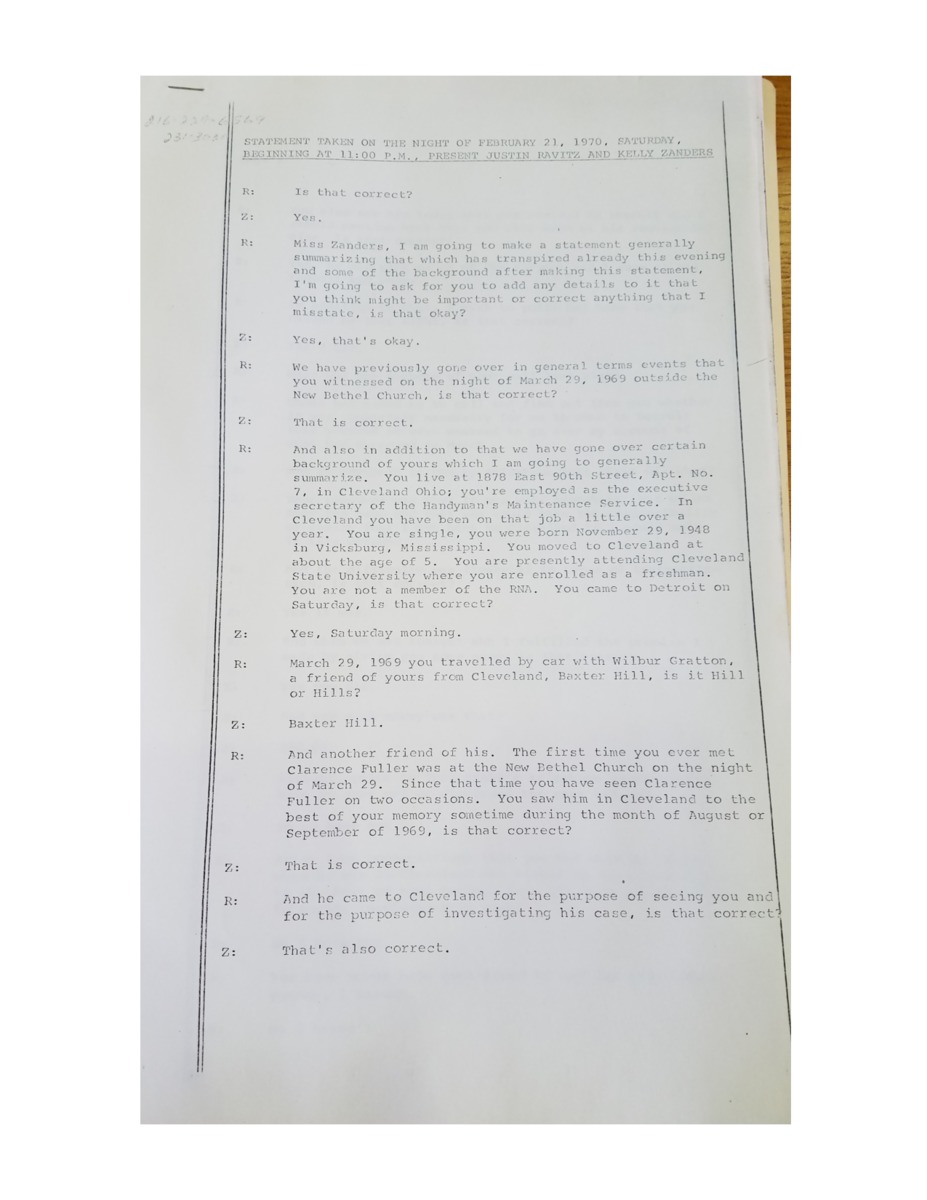

Kelly Zanders, a 20-year-old African American female from Cleveland, was attending the RNA convention (but was not a member) and gave her sworn statement to the lawyers for the defendants charged with murdering Patrolman Czapski. She witnessed the confrontation and was not interviewed by the DPD Homicide Bureau. Zanders stated that she left the church with Wilbur Gratton and Clarence Fuller and immediately saw a shorter (approximately 5'5'') black man in a green uniform with a white belt "firing a rifle" at another male who was crouched on the sidewalk. She took cover and heard several more bursts of gunfire in the next 15 minutes or so. She also specified that the murder trial defendant Clarence Fuller (known as Chaka, although the transcript below says Choka) was with her the whole time and never fired a gun.

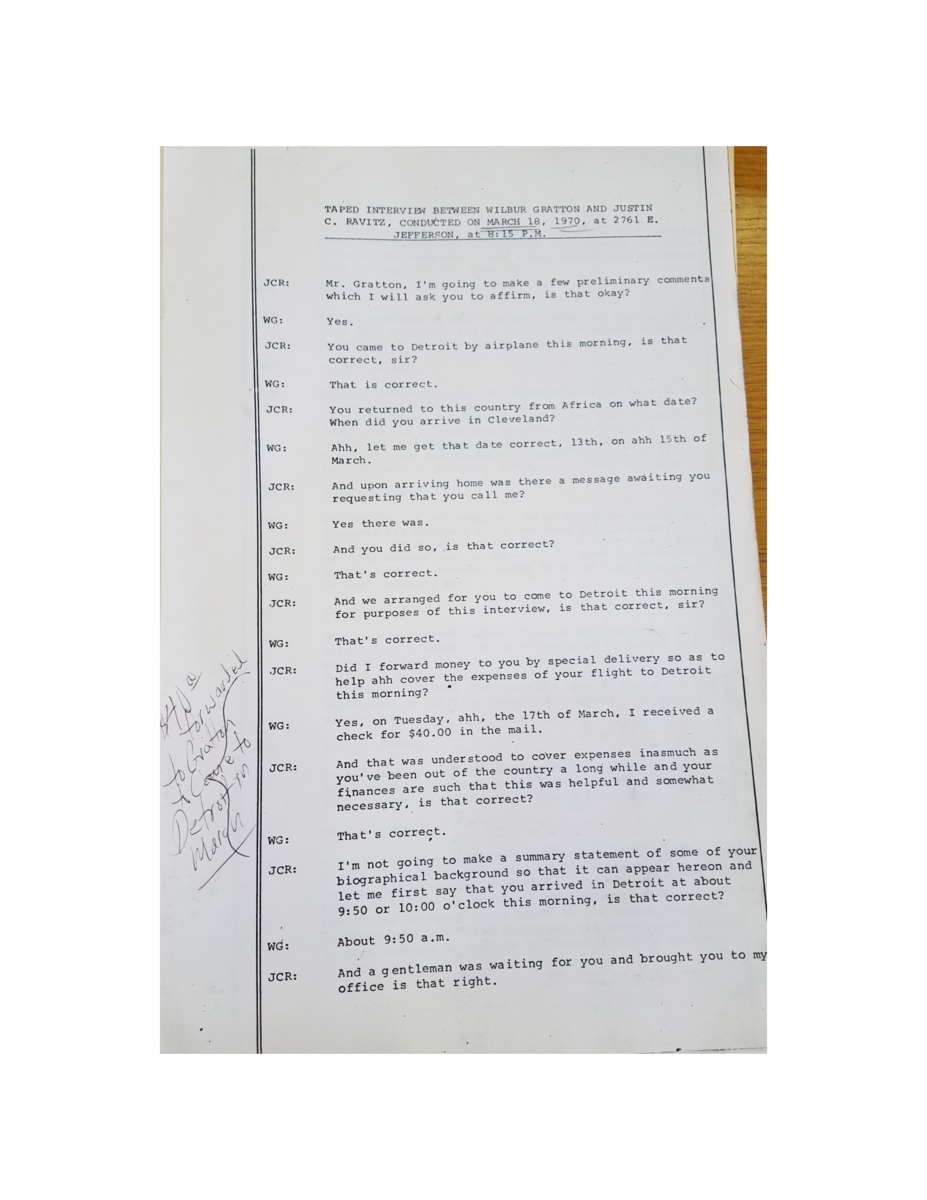

Wilbur Gratton, a 50-year-old African American and RNA member from Cleveland, also gave his sworn statement to the defense. Gratton left the church in the company of Kelly Zanders and Clarence Fuller (Chaka). Gratton saw a man shooting a rifle, whom he described as dark-complexioned and around 5'9'' and wearing a green uniform, and another man "lying prone on the sidewalk." The man with the rifle also fired at the police car. Gratton also insisted that Clarence Fuller was not the shooter and was not armed.

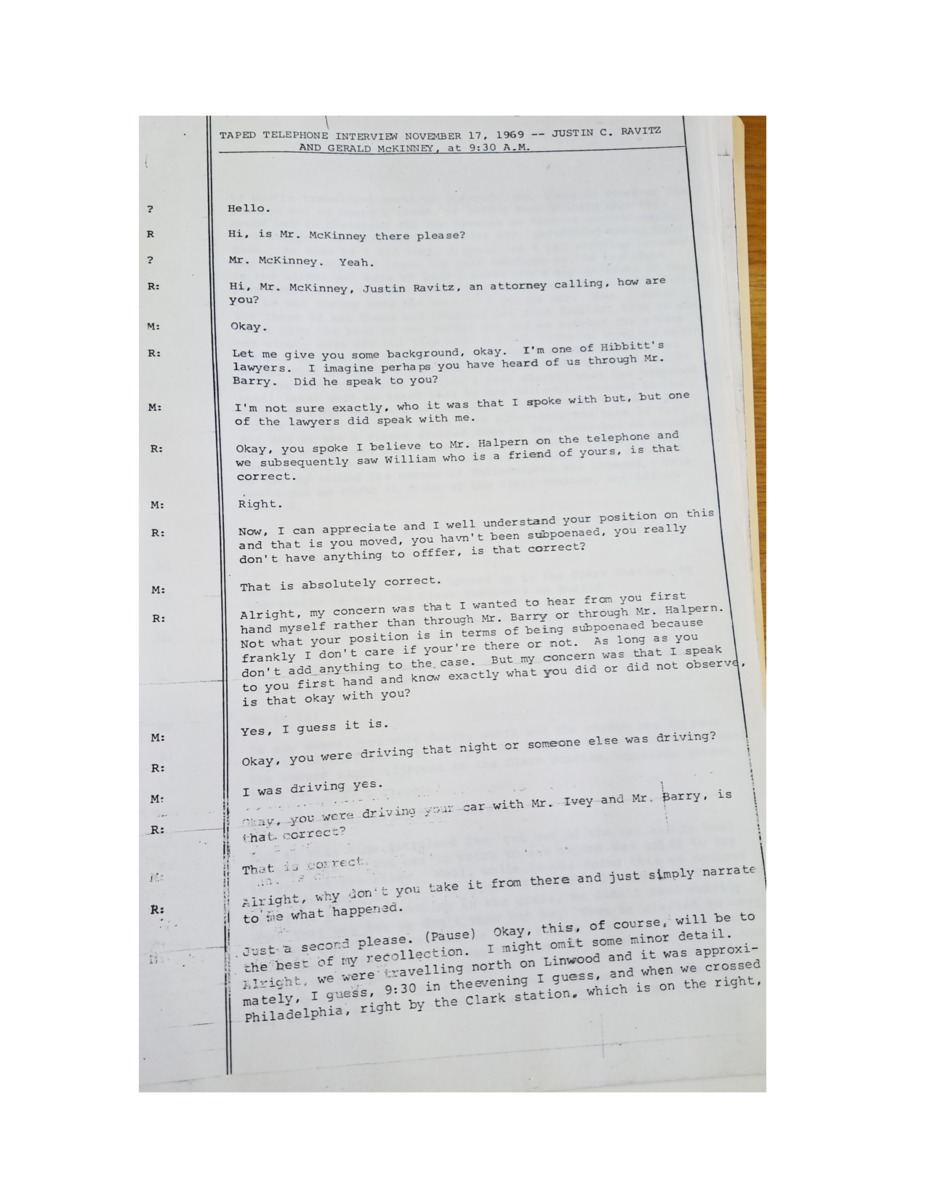

Gerald McKinney, an African American man, was not in attendance at the RNA rally and was driving by. He heard gunfire and stopped the car. He saw a man with a rifle standing near the rear entrance to the New Bethel church, "firing into the back of a police car" four to six times. The police car (driven by a wounded Patrolman Worobec) then began driving away and crashed. McKinney also stated that Clarence Fuller was not the shooter. He described the shooter as taller than 6' and a black male. McKinney further stated that multiple police officers were already on the scene during the initial confrontation, and that he saw police fire into the church and shots come from the church at the police.

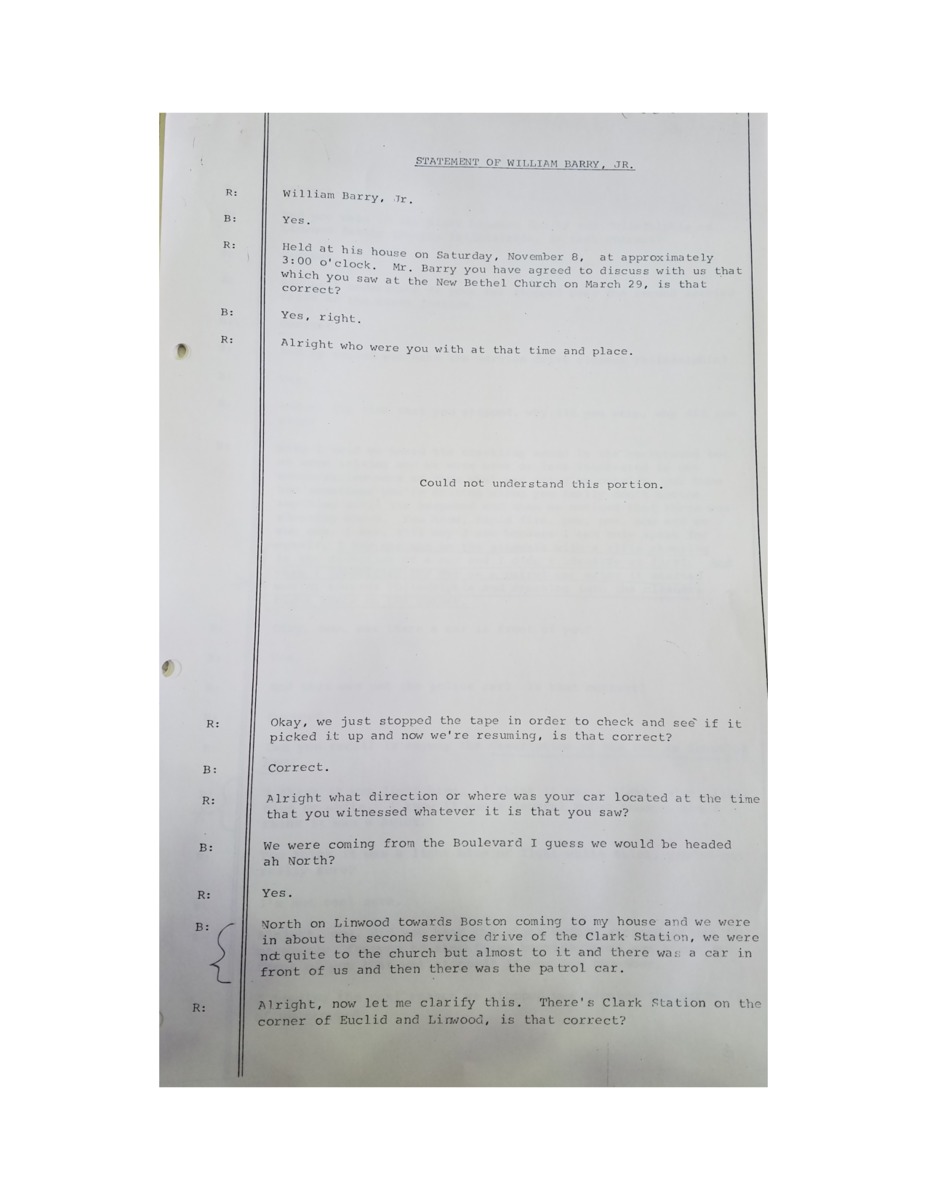

William Barry, Jr., an African American man, was riding in the car with Gerald McKinney when they heard gunshots. He saw "one man on the sidewalk" shooting toward the patrol car. He believed the man was about 6' tall. He also saw other unmarked cars with police officers inside them already on the scene. Barry further stated that about 15-20 police arrived "within seconds" and began shooting at RNA members on the street and into the church, another indication that the police presence in the area was already considerable at the time of the initial confrontation. He stated that he saw minimal fire coming from inside the church and maximum fire coming from the police outside.

Review the statements by these four African American witnesses in the gallery below.

What Happened Inside the Church?

There were 142 African Americans, including many women and children, still inside the New Bethel Baptist Church during the police assault that began around five minutes after the shooting outside. The police fired at least 100 rounds into the church before and during the invasion. The civilians took refuge and later described a campaign of racial terror and indiscriminate vengeance by the invading officers, as they tried to surrender and after they were prisoners.The police officers who invaded the church arrested them all and booked everyone for conspiracy to commit murder.

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations investigation stated that all civilian witnesses agreed that the man who shot the police officers did not flee into the church. The DCCR also found no evidence that anyone inside the church fired on the police: "a painstaking examination of the church interior, exterior, and the immediate surroundings, however, does not reveal any evidence to support this claim," and forensic evidence shows that the bullet holes all came from shots fired from the outside, except for a couple that were presumably fired inside by police. The Detroit Free Press reported more than one hundred bullet holes in the church walls behind the front door, which means that the police contingent fired extensively into the church before entering.

DPD Version. The Detroit Police Department claimed that the group of 10-12 assailants who shot the two officers fled into the New Bethel Baptist Church. The DPD says the backup contingent then encountered "a hail of gunfire" from inside the church, entered the building in order to counter the attack, fired inside the church only at people who presented a direct threat, and followed proper police procedure in arresting everyone present.

The edited and partial police radio log transcript provided to investigators by the DPD includes alleged calls from squad cars stating "officer shot from the church," "officer shot from inside the church," "between 10 & 12 of them and they are armed with carbines in the church," and "the ones who shot that officer are in the church."

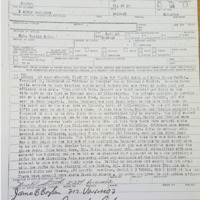

DPD Sgt. Harold Smith. The incident report filed by Harold Smith (below left), one of the ranking officers on the scene, states that he and his partner responded to the "officer in trouble" alert, helped load the two wounded officers into squad cars bound for the hospital, and then an unidentified N/M ("Negro male") told the group of officers that "there were several men in the church with rifles." Smith then reported that shots were fired from the entrance of the church, and he led a contingent of officers inside, breaking down the front door. Smith claimed they ordered the occupants of the building to "come out with their hands up," saw "what appeared to be a man pointing a rifle in our direction," and began firing. He further stated that a Patrolman Boylan fired at an unidentified man who was "crawling along the floor" and refused to halt. They captured the occupants of the building, searched them, and transported them to headquarters. Smith's report obviously omits many crucial details.

Ralph Williams, an African American man, was the janitor for the New Bethel Baptist Church and on the scene. The DCCR investigation valued his perspective because he was not a RNA member. Williams observed that the RNA leaders had armed bodyguards that evening, about 12 in total. Most if not all of them left around 11:30 p.m. Then (presumably after the shooting outside) Williams stated that police officers shot through the front door of the church with rifles and the people who were still inside scattered in terror, hiding under church pews and running down to the basement. The police officers herded them together and forced everyone back up into the lobby.

Ralph Williams also witnessed the police shoot two unarmed people who posed no threat and threaten the lives of several more:

Ralph Williams said that around 25 white police officers were choking, berating, and abusing the African Americans herded together in the lobby. He also observed around four black officers who had their guns drawn but were not participating in the abuse. Williams, who was arrested along with everyone else inside, insisted that nobody inside the church fired any shots at any time during this sequence of events (below, second from left).

Undercover FBI informant. The informant from Cincinnati, who was still inside, stated that "dozens of shots were fired into church" by the police and that some of the RNA security guards inside were armed, but they "did not fire." A RNA member asked everyone inside to remain calm and go to the basement. Many people inside expressed fear regarding the large number of women and children present. The next paragraph of the informant's account is completely redacted and likely describes illegal police action against the people inside. This is the same source who reported the consensus among RNA members that "police fired first" in the initial encounter outside (read full account here).

Detroit Commission on Community Relations. The DCCR's extensive investigation, in addition to emphasizing that the civilians inside did not fire on the police, found that the officers who invaded the church committed "physical brutality in considerable amounts," constantly shouted racist epithets, and shot four people, including at least two who had already surrendered. The DCCR considered it "nothing short of miraculous" that the actions of the police had resulted only in four gunfire casualties inside the church and no additional deaths. The DCCR also agreed with civil rights advocates (section below) that the mass arrest of everyone inside was illegal and that "basic constitutional rights of the prisoners were flouted."

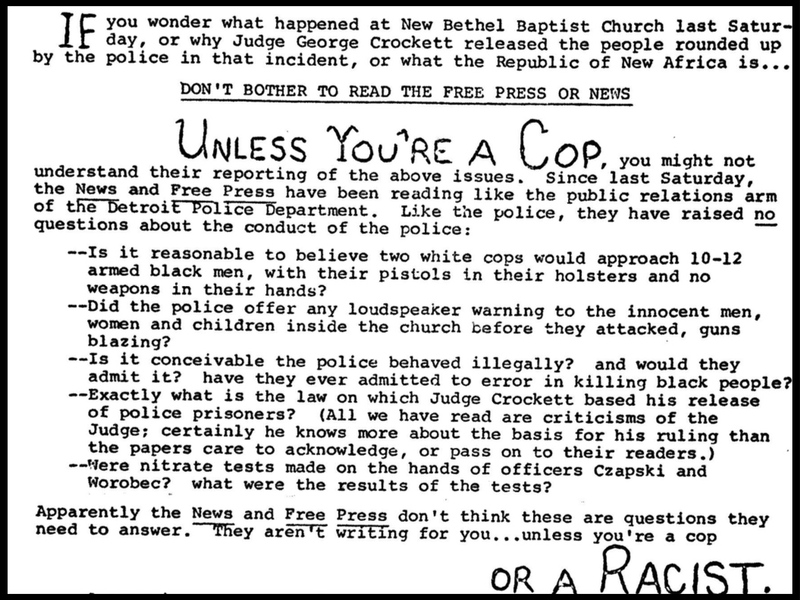

Detroit Newspapers. The mainstream Detroit newspapers reported the New Bethel Incident in biased, sensationalized, and factually incorrect articles that inflamed racial tensions and comprehensively took the side of the police. The Detroit News's initial story on March 30 stated that the police had been "ambushed by a gang of 10 or 12 men." This coverage recycled the police version at face value and adding the inflammatory and factually inaccurate verb "ambush," which referenced the same newspaper's false hype about sniper attacks by a black militant conspiracy during the 1967 Uprising and grammatically cannot be a truthful desciption of an encounter initiated by the police. The Detroit News also uncritically propagated the police cover story that "gunshots were fired from inside the church" and defended the mass arrest of all 142 people present. During the next week, the Detroit News ran many articles hyping the allegedly violent threat of black militants in Detroit and throughout the United States. The Detroit Free Press also reported the initial story inaccurately, based on the police side, but later ran a correction and also raised concerns about whether the mass arrest violated the civil liberties of the people inside the church.

Read competing accounts of what happened inside the church in the gallery below.

Judge Crockett's Intervention and Law Enforcement Backlash

At 5:00 a.m. on March 30, Judge George Crockett received calls alerting him to the situation from two civil rights leaders, Rev. C. L. Franklin of New Bethel Baptist Church and state representative James Del Rio. They told him that the First Precinct was holding a large number of prisoners and now allowing anyone to gain access to them, in violation of constitutional protections. Crockett headed to the precinct station and asked for a list of the names of the prisoners, who had been there about six hours by the time he arrived, but the police didn't even know who was in custody. Crockett then called Police Commissioner Johannes Spreen, demanding such a list, and proceeded to set up a temporary courtroom inside the precinct station house. He summoned an assistant prosecutor and the news media.

Crockett began holding habeas corpus hearings to determine if the police had evidence to hold the 142 prisoners. The judge made it through 30 of the cases, with some released on $100 bond, other non-residents remanded to police custody with a noon deadline to produce evidence, and freeing Ralph Williams, the church janitor who was just there to close up the building.

Then William Cahalan, the Wayne County prosecutor, arrived and ordered the police not to comply with Judge Crockett's direct orders, specifically not to produce any more prisoners for the habeas corpus hearings. Cahalan specifically wanted more time for the police to run chemical analysis tests on the hands of all 142 prisoners to see which of them might have fired a gun, but the judge said that this was unconstitutional since the DPD had deliberately refused to allow those arrested to have access to attorneys. Crockett then threatened to hold Cahalan in contempt and also later accused the prosecutor of racism in his disrespect and defiance of the lawful actions of a judge. After this conflict, the hearings continued and Judge Crockett released 130 of the 142 persons in total, most with the agreement of the prosecutors present.

Prosecutor Cahalan and the mainstream news media then radically distorted what had actually happened in the hearings that released all but 12 prisoners, leveling harsh accusations that Crockett had acted in a biased way because of his race and out of hostility to law enforcement, implying he was sympathetic to violent black militants. The Detroit News labeled Crockett's conduct "hostile and inflammatory" (which is exactly how the DCCR described the News's coverage of this controversy in its own investigation). DPD superintendent John Nichols stated that all of the people inside the church had been properly charged with conspiracy to commit murder, because the police needed the time to interrogate them and investigate the scene to determine who the specifically guilty parties were--in effect defending the illegal policy of investigative arrests that civil rights groups had been denouncing since the late 1950s.

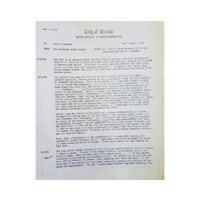

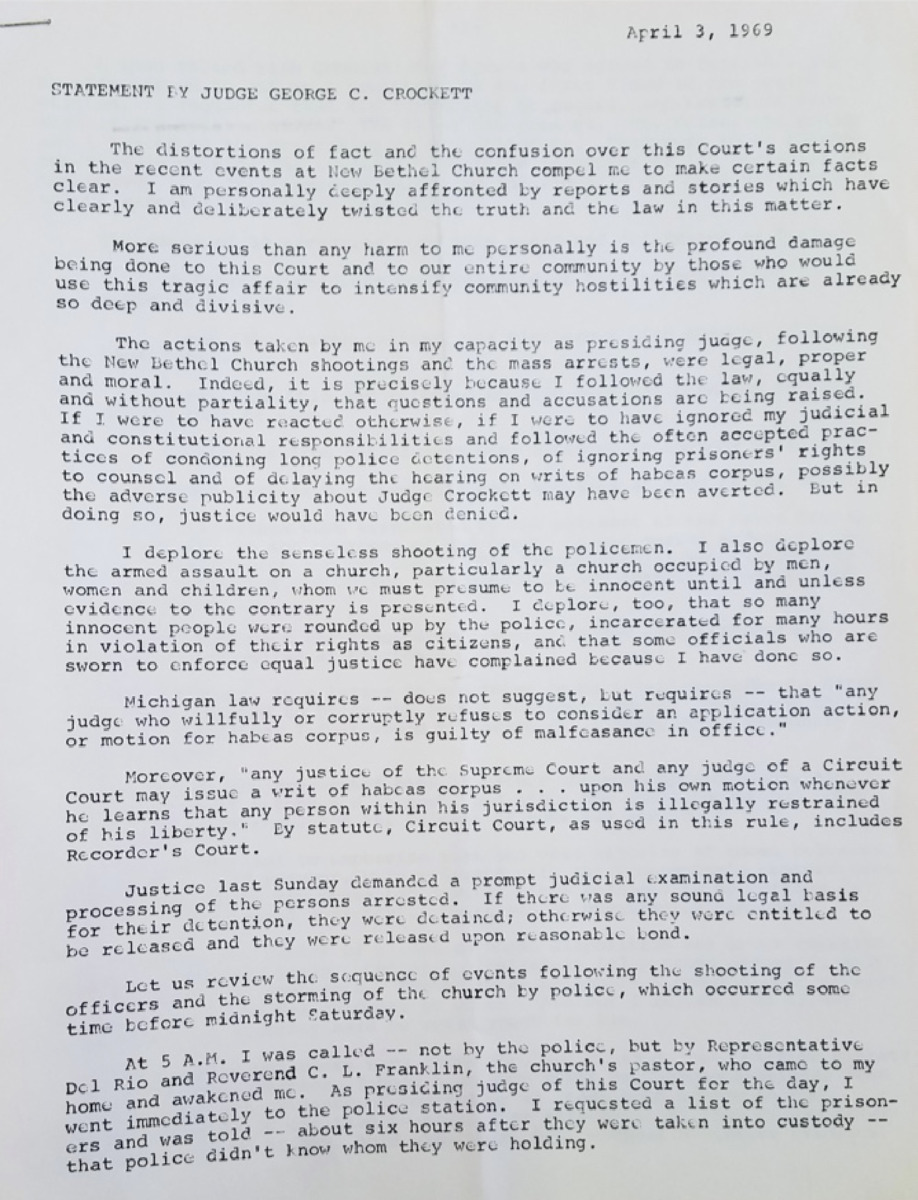

Judge Crockett responded with an unusual public statement (below left) recounting what had actually happened and also accusing the police department, as quoted above, of an unjustified "armed assault" on a black church, that would never have happened in a white neighborhood, and violation of the constitutional rights of the citizens rounded up in the mass arrest. Crockett further charged that Prosecutor William Cahalan was angry because a jurist doing his duty as part of an independent judiciary had challenged the "ordinary and undemocratic police practices" of the DPD. He concluded: "I intend to continue to maintain law and order in my courtroom by dispensing justice equally and fairly." In additional public commentary, Crockett rejected the prosecutor's charges that he had let around ten specific murder suspects go free and stated, "I will not lend my office to practices which subvert legal processes and deny justice to some because they are poor or black."

The Detroit Police Officers Association union launched a bitter campaign against Judge Crockett during April 1969, part of its broader mobilization in city politics as a right-wing force. The DPOA organized an anti-Crockett demonstration in front of the Recorder's Court attended by 300 police officers and announced a campaign to remove the judge for alleged misconduct. The DPOA took out a full-page advertisement in the Detroit News to announce this effort and tell what it claimed to be the "complete story of the assassinatin of Patrolman Czapski" (right). The DPOA's manifesto repeated the cover story that black militant "guerillas" had ambushed the two officers outside the church and then fired on their backup from inside, even claiming that snipers were firing on the police from the church altar and loft. After this series of lies, the DPOA also disingenuously defended Prosecutor William Cahalan against what it alleged was judicial misconduct by Judge Crockett in his desire to free the black militants no matter what. In its attack, the DPOA also denounced Judge Crockett as biased because he had presided over the arraignment of a police officer for felonious assault in the Veterans Memorial Incident a year earlier, when drunken off-duty policemen defended by the DPOA had brutally attacked a group of black teenagers. The DPOA's intervention was practically a declaration of war against a new political challenge for white law enforcement in Detroit: an African American judge who was deeply respected by civil rights organizations and not afraid to speak out against police and prosecutorial misdonduct.

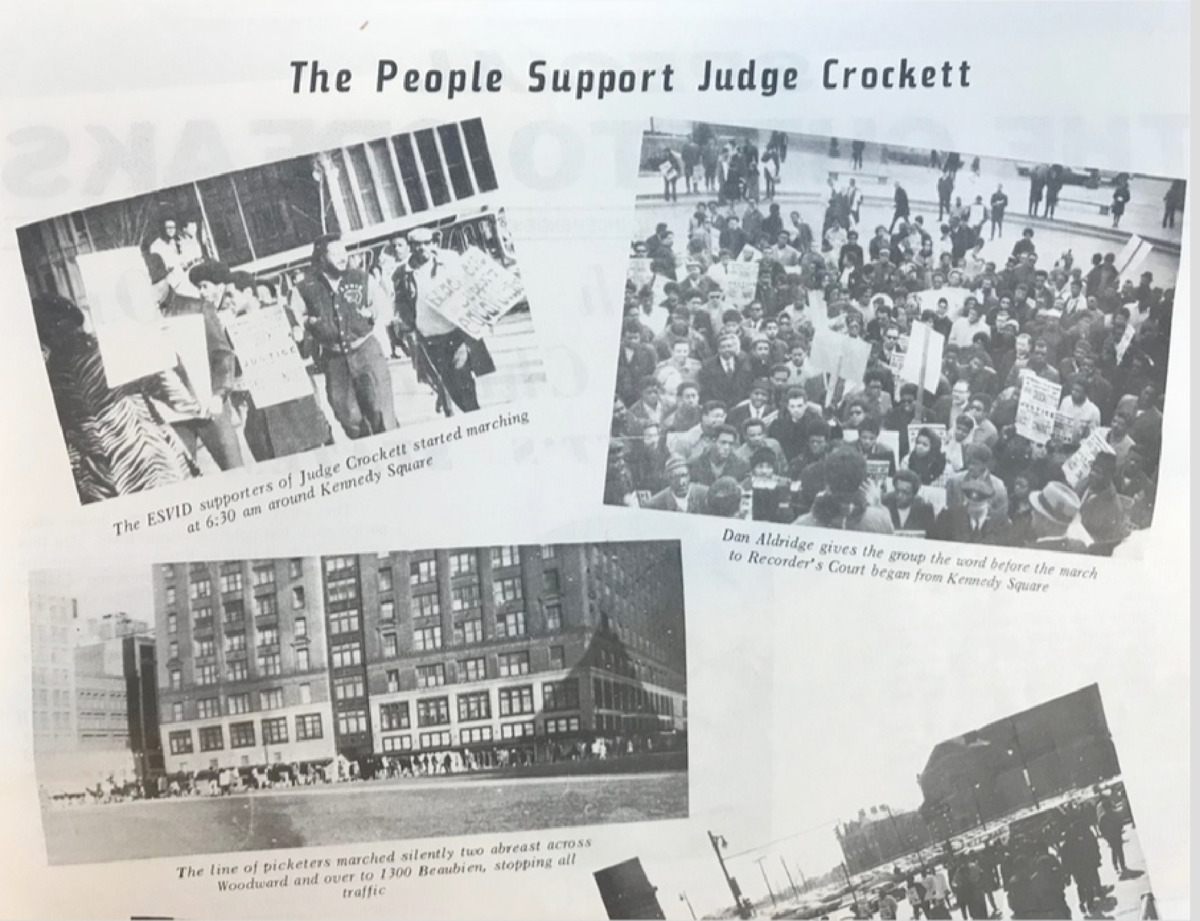

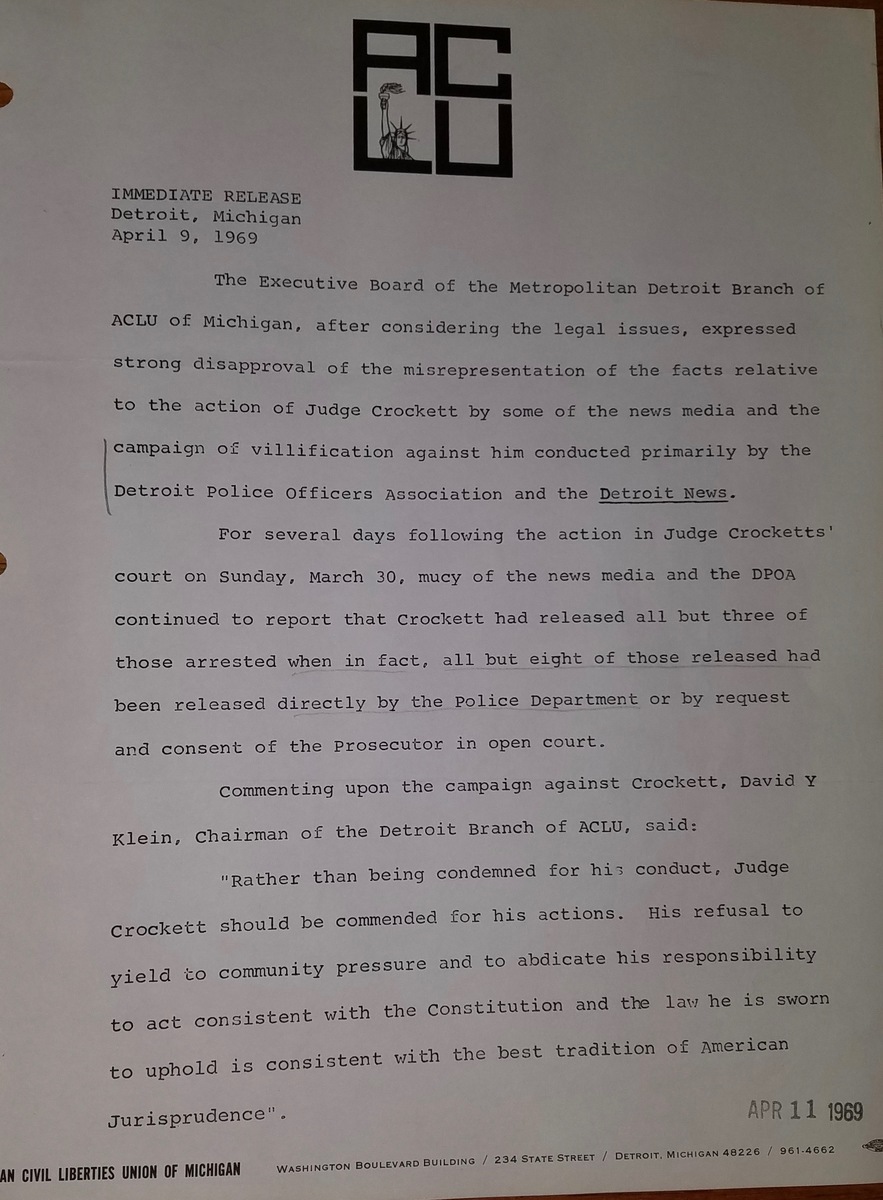

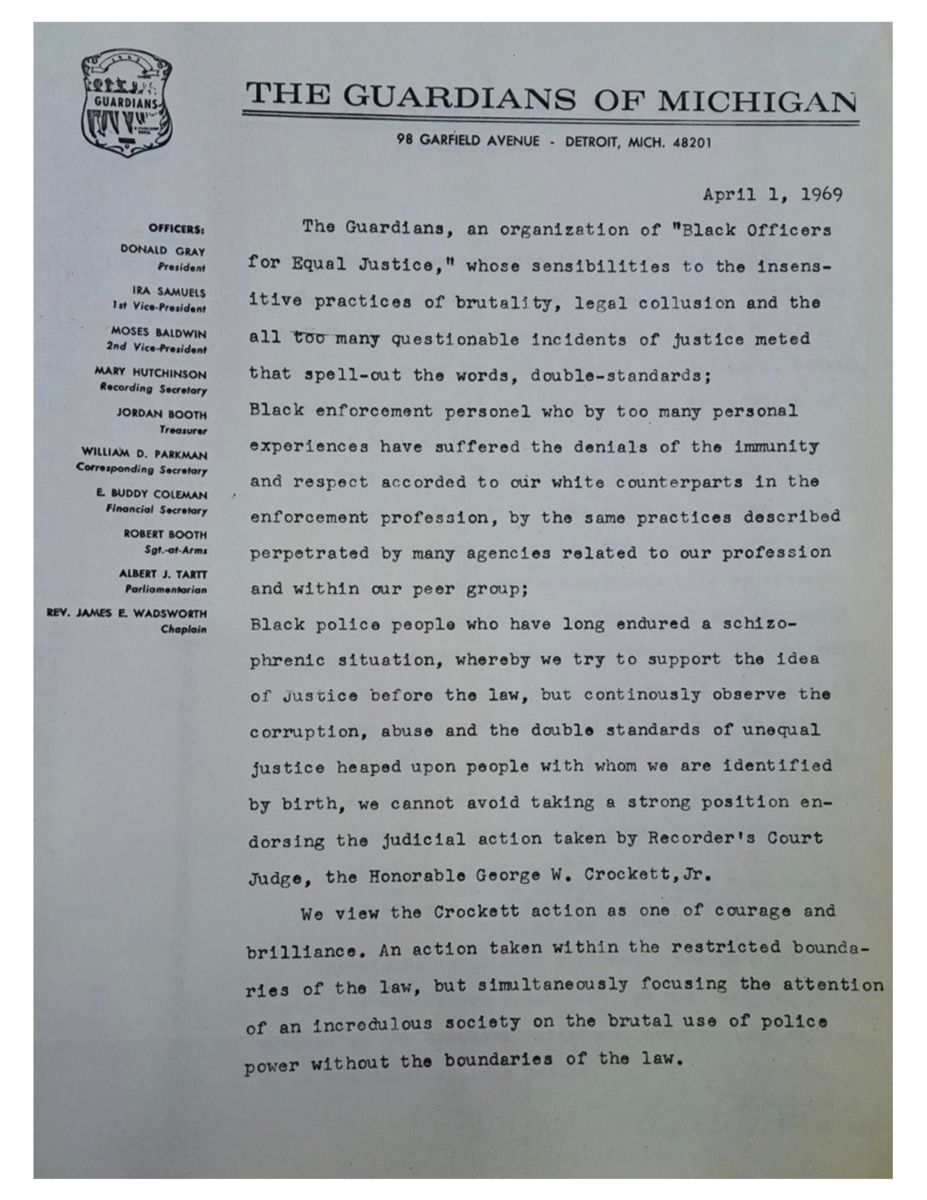

Black power and civil rights groups mobilized quickly to defend Judge Crockett against the attacks by the prosecutor, police department, and mainstream newspapers. The East Side Voice of Independent Detroit, a militant community organization, headlined its coverage "Police Launch Assault on Black Church," held a march and rally outside Recorder's Court in downtown Detroit, and picketed the DPD headquarters. The Detroit chapter of the ACLU denounced the news media and the DPOA union for its "campaign of villification" against Judge Crockett and praised him for "his refusal to yield to community pressure," which presumably meant the white and law enforcement communities, because the support for him among African Americans was overwhelming. The Guardians, the professional association for black police officers, praised Judge Crockett for his "courage and brilliance" and strongly denounced the DPD's actions at New Bethel as "the brutal use of police power without the boundaries of the law."

Examine Crockett's statement and other documents defending his actions in the gallery below.

The New Bethel Trials

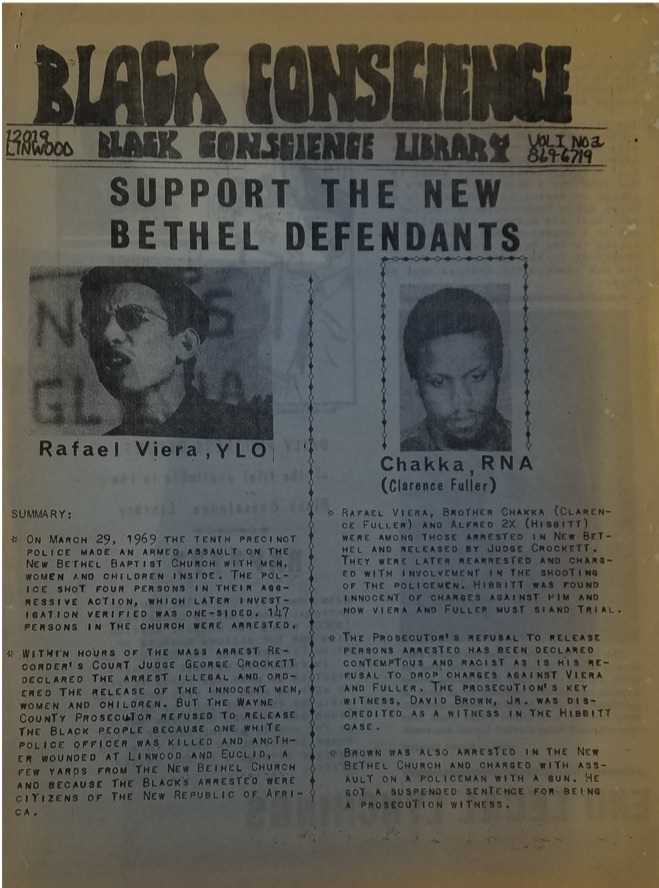

Black nationalist groups in Detroit mobilized to defend the Republic of New Africa, and many civil rights groups also criticized the DPD and Wayne County prosecutor for a rush to judgment and for the mass criminalization of everyone inside the church. People Against Racism, a white New Left organization, held a protest march and stated that based on the long history of racist violence against black people in Detroit, the DPD did not deserve the benefit of the doubt and was almost certainly orchestrating a coverup with the prosecutor's involvement.

RNA leaders accused the DPD of a "conspiracy to destroy the RNA" and specifically contended that the operation that night at New Bethel Baptist Church had intended to kill vice-president Milton Henry (Brother Gaidi). The RNA also accused Prosecutor William Cahalan of not caring at all that police officers shot four RNA members at point blank range after they stormed into the church. The RNA even implied that Patrolmen Czapski and Worobec might have been "innocent pawns" in this broader law enforcement conspiracy.

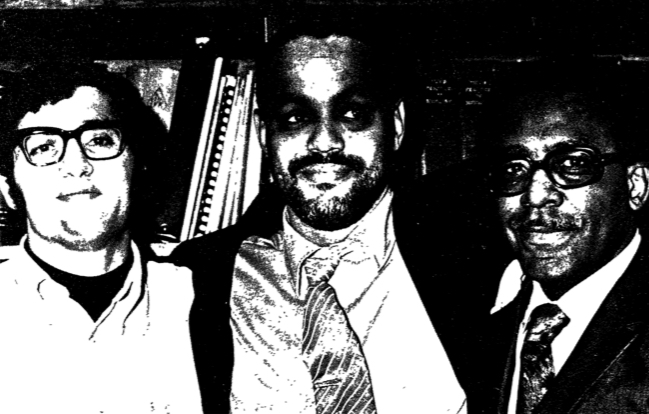

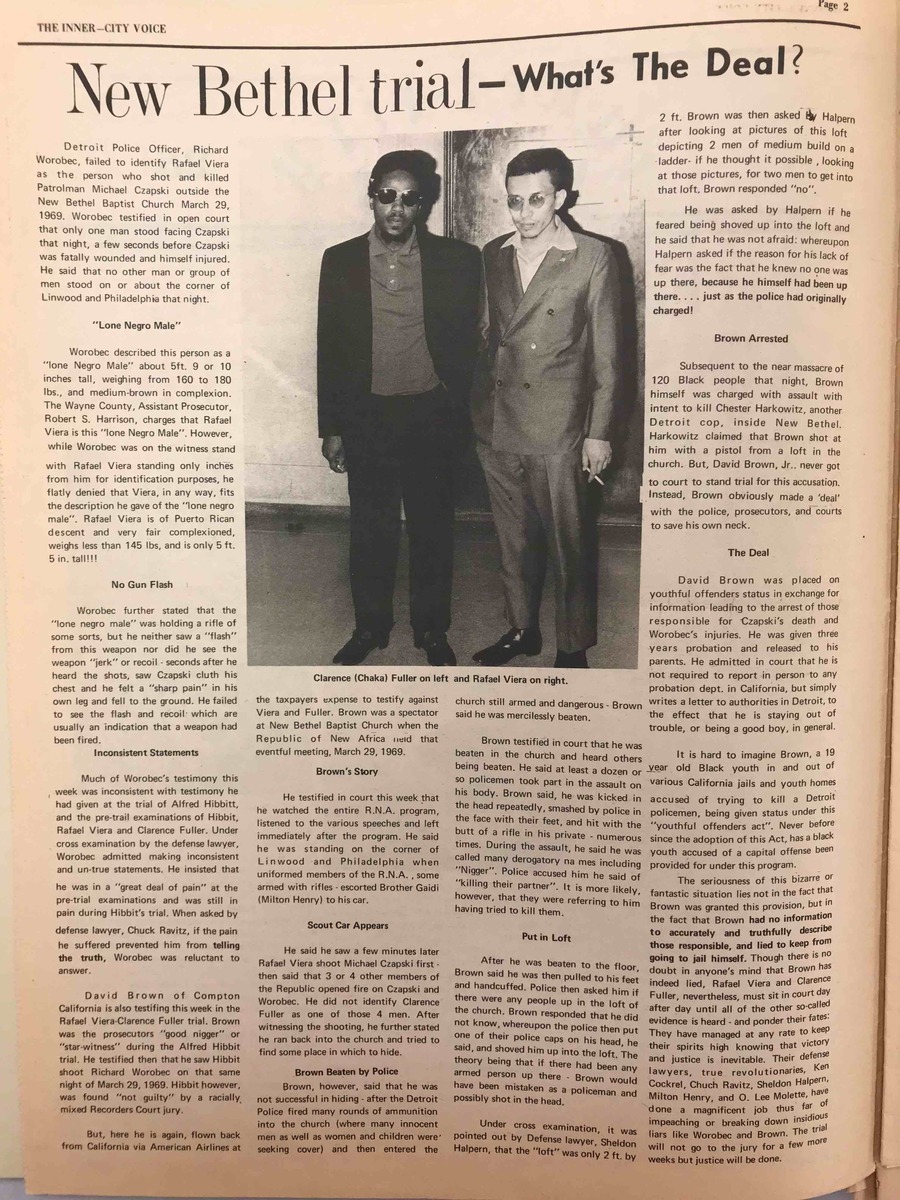

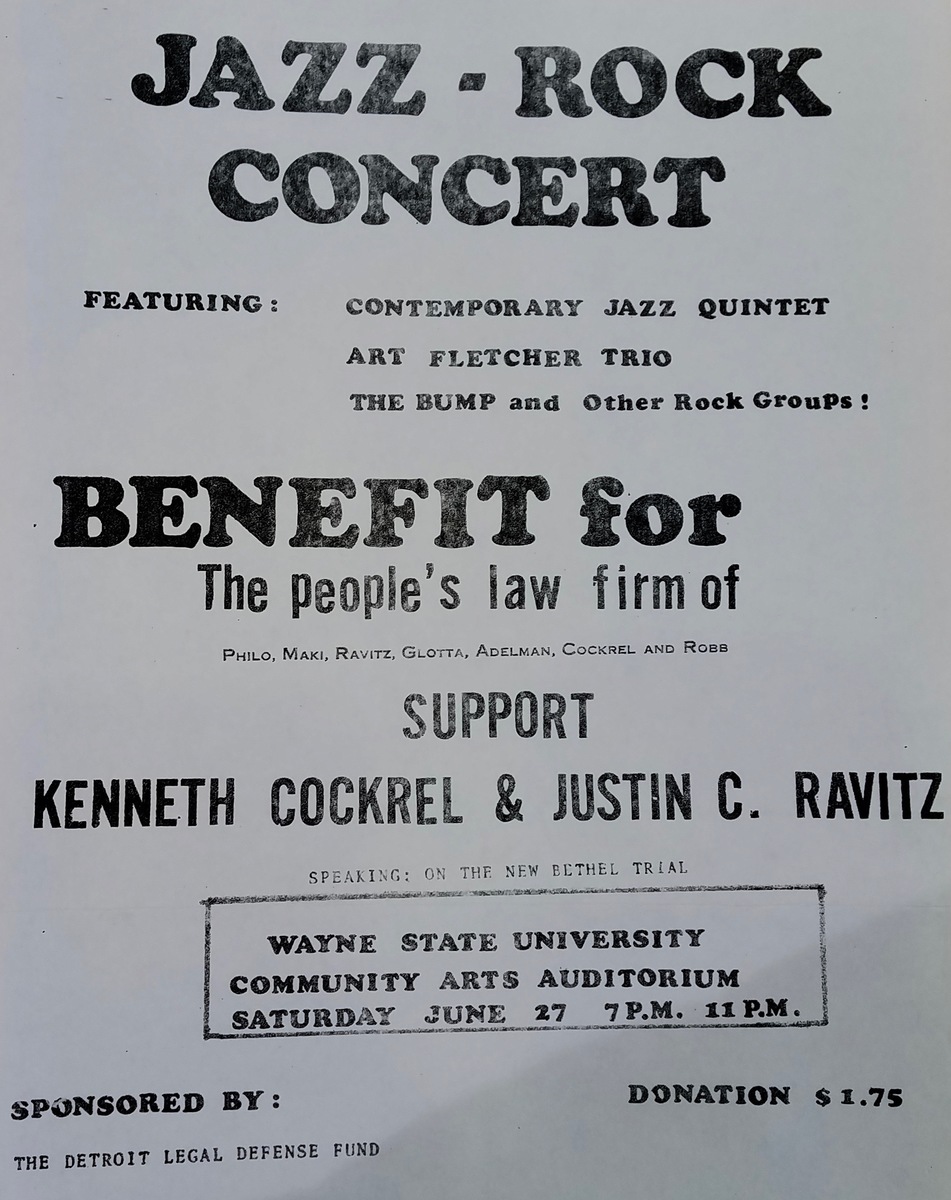

The Wayne County prosecutor ultimately took three men to trial with the murder of Patrolman Michael Czapski and the attempted murder of Patrolman Richard Worobec in the initial confrontation outside of the Republic of New Africa rally at the New Bethel Baptist Church. There were two separate proceedings, which became known as New Bethel I and New Bethel II. The defendant in New Bethel I was Alfred Hibbit (aka Alfred 2X), and the defendants in New Bethel II were Clarence (Chaka) Fuller and Rafael Viera (who was from New York City and was Puerto Rican). Two radical young attorneys led the defense team, Kenneth Cockrel, an African American, and Justin Ravitz, of the white New Left. In many ways, both sought to put the entire law enforcement and criminal justice system on trial, and Cockrel even faced a contempt proceeding after he called the judge in one of the cases a racist.

The preponderance of testimony from witnesses pointed to a single shooter, although the DPD and the prosecutor's office continued to insist that a larger group of RNA bodyguards were responsible. Patrolman Worobec, the wounded officer, was not able to positively identify any of the defendants as the assailant(s) and ultimately gave inconsistent testimony at the two trials that weakened the prosecution's cases. The defense attorneys even got Worobec to admit that he had made statements during pretrial examinations that were not accurate, for which he blamed his pain during the recovery process. In the second trial, Worobec stated that a "lone Negro male" had done the shooting and specifically said that Rafael Viera was not that person. Another officer contradicted this account by stating that Worobec had told him that "10 to 12 Negroes" shot him and then ran into the church, which conveniently supported the DPD's official line but does not appear to be what Worobec remembered.

The main prosecution witness was David Brown, who was a juvenile from Compton, California, an African American area right outside Los Angeles, and is quite possibly the undercover FBI informant that J. Edgar Hoover authorized to be compensated for attending the RNA convention. The prosecutor had initially charged Brown with assault with intent to kill a police officer inside of New Bethel Church, and it seemed on the surface that his decision to become a cooperating witness was based on a deal to reduce these charges to three years probation. But it is also possibly and perhaps likely that the initial felony charge against David Brown was a facade to mask his role as an undercover informant. A known FBI tactic was to recruit young African American men who had been arrested to become undercover informants in exchange for leniency, and it is possible that this is why Brown flew to Detroit from Los Angeles in the first place.

David Brown's testimony was quite convenient for the prosecution and also very dubious, as he claimed to have seen everything that happened both outside and inside the church. At the New Bethel I trial, Brown testified that he had been outside during the initial confrontation and had seen Alfred Hibbit shoot Richard Worobec. At the New Bethel II trial, Brown testified that Michael Czapski had approached a group of 4 armed RNA members, yelled "wait a minute," and then Rafael Viera turned and started shooting at him. Then, he claimed, Hibbit and two other RNA bodyguards began firing at Richard Worobec. Brown did not identify Clarence Fuller as one of these shooters (and recall that in the previous section, both of the witnesses who were with Fuller denied that he had been involved in any way). Brown furthermore testified that police officers had beaten and kicked him during the assault on the inside of the church. He did not end up persuading either jury.

The defendants in both New Bethel trials were acquitted of all charges. The juries were racially mixed, which had not generally been the case in previous high-profile trials involving alleged police misconduct in Detroit, especially because prosecutors often used preemptive challenges to remove black jurors. Attorneys Kenneth Cockrel and Justin Ravitz successfully challenged this practice in the New Bethel cases and obtained juries not inclined to rubber-stamp the prosecutor's case. The defense team also accused the police department and prosecutor's office of many illegal and improper activities and argued that much of the evidence should be suppressed because it had been obtained through the unconstitutional mass arrest inside the church. In the end, though, the juries acquitted because the prosecutor did not present compelling evidence that any one of the men was the lone shooter that the most reliable witnesses and the surviving police officer had testified to but could not clearly identify.

There are still a lot of unsolved mysteries in the New Bethel Incident, including the extent to which the DPD officers escalated the initial confrontation and why the prosecutor chose to take these three particular defendants to trial. It definitely seems likely that a member of the Republic of New Africa, when confronted by two white police officers whose guns, despite the DPD's insistence, were almost certainly drawn, and who may have fired first, shot and killed one of them and wounded the other. The investigations definitely established that the DPD contingent that invaded the church wrongfully shot four unarmed people, brutalized dozens more, and fabricated a cover story of being attacked by snipers inside. It is also possible, to end with another mystery, that one of the defendants was actually also operating as a deep undercover police or FBI informant in the government campaign to destroy the Republic of New Africa.

View documents in the gallery below from the defense of the defendants in the New Bethel trials by black nationalist organizations in Detroit.

Sources:

Albert B. Cleage, Jr., Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

William G. Milliken Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Inner-City Voice, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Vertical Files Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Department of Civil Rights, Community Relations Bureau, RG 83-55, Michigan State Archives, Lansing, Michigan

New Bethel Defense Fund Benefit, 1969, Folder: 100388-003-0542, The Black Power Movement: The League of Revolutionary Black Workers, 1965-1976, ProQuest History Vault

"Riots, Civil, and Criminal Disorders," Part 20, Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Government Operations, United States Senate, June 26 and 30, 1969 (Washington: GPO, 1969)

The Republic of New Africa Collection, FBI Library, Federal Surveillance of African Americans, 1920-1984, Archives Unbound

"The Linwood Incident: A Detailed Report," Detroit Free Press, March 31, 1969

Detroit News, April 13, 1969, April 19, 1969

David Cunningham, There's Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and the FBI Counterintelligence (2005)

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

Christian Davenport, How Social Movements Die: Repression and Demobilization of the Republic of New Africa (2014)