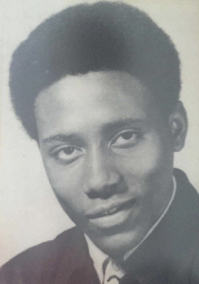

Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell

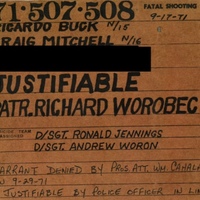

On September 17, 1971, a "Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets" (STRESS) unit led by decoy officer Richard Worobec fatally shot two unarmed Black teenagers, 15-year-old Ricardo Buck and 16-year-old Craig Mitchell. Patrolman Worobec, who was not injured, claimed that Buck and Mitchell attacked him with a steel rod, beat and kicked him, stole his watch, and fled when he identified himself as an officer and ordered them to halt. Worobec insisted that only then did he fire his revolver at both boys, "purely on instinct," killing both with gunshots to the back as they fled in different directions.

Multiple witnesses disputed the incident account by Worobec and the other members of STRESS Team 4, stating that more than one white officer fired on the Black youth for no reason and at close range, "in cold blood," and that a white officer planted the watch under Buck's body after his death.

The physical evidence--reexamined by our project through a Freedom of Information Act request of the DPD Homicide Bureau's investigative file--provides significant information, in combination with the eyewitness accounts, indicating that the DPD covered up key details of the encounter. In particular, a police officer shot Ricardo Buck in the chest, and two different types of bullets entered his body from two different directions, contrary to the cover story provided by Patrolman Worobec and other officers on the scene. The shifting and inconsistent statements of the police officers present--which have never been made publicly available before now--also overwhelmingly indicate that Patrolman Worobec planted the watch on the dead youth and very likely fabricated the "steel rod" attack as well.

A Pattern of Unjustified Force. In addition, it is relevant contextual evidence that STRESS teams fabricated the incident accounts and planted weapons on their victims in a demonstrable majority--and quite possibly all--of the unit's 14 fatal decoy operation shootings during 1971-1972 (see the "Remembering STRESS Victims" page for detailed accounts, and click here to learn more about STRESS's origins and agenda). In at least half of these incidents, STRESS officers claimed to shoot Black males armed with knives or other weapons in the back as they fled--but the forensic evidence, autopsy reports, testimony of surviving eyewitnesses, and civil litigation revealed that the undercover decoy actually shot the unarmed victim from the front in the chest or stomach, usually at close range and unprovoked. There is a strong pattern of evidence that the STRESS units planted weapons on the people they shot in order to clean up the crime scene and ensure that the homicide would be "justifiable." These broader patterns are necessary and crucial context for assessing the veracity of the very similar stories that Patrolman Worobec and his decoy unit told about the fatal shootings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell--and in evaluating whether Worobec actually instigated the encounter and shot Ricardo Buck in the chest before either youth began to flee and then lied about what happened, with the complicity of his backup team.

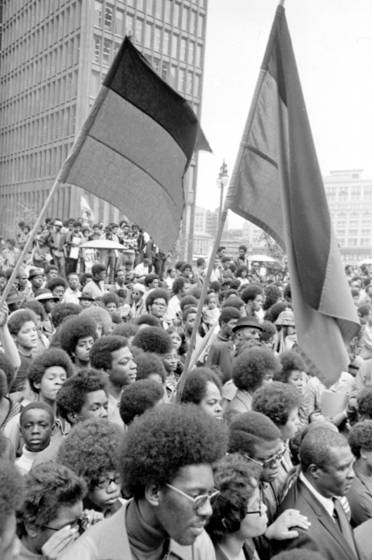

A Pattern of Law Enforcement Coverups. The archival evidence makes clear that the Homicide Bureau's "investigation" was perfunctory, incomplete, and clearly designed from the outset to exonerate Patrolman Worobec. The separate investigation by the Wayne County Prosecutor also took the police officers' accounts at face value and sought to discredit and dismiss all countervailing evidence. This approach fit into the broader pattern, both throughout the civil rights era covered in this exhibit and during the STRESS era of the early 1970s specifically, of the Detroit Police Department and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office declaring almost all police killings to be "justifiable homicides" regardless of the actual circumstances. In response, civil rights groups charged the DPD and prosecutor with a coverup of murder and demanded changes to STRESS's shoot-first policy, while a broad coalition led by black power activists organized massive protests in the streets and called for the abolition of STRESS entirely (detailed on the following page).

Excessive Force as a Product of Public Policy not just Individual Officers

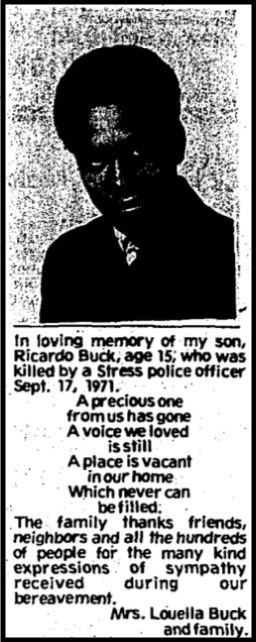

The killings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell generated enormous controversy and turned out to be a key turning point in the history of STRESS. DPD officers in the undercover decoy unit had already fatally shot seven people in the previous six months, mostly African American males in their 20s, but none of these cases received media attention or mobilized civil rights and anti-police brutality activists. The shooting of two young teenage boys was different, creating widespread shock and outrage across the Black community. The involvement of Patrolman Richard Worobec also heightened suspicions of police-instigated violence, particularly for black power organizations, since he was the same officer who had been wounded in the murky shootout with black nationalists that set off the New Bethel Incident barely more than two years earlier, and his STRESS unit had killed another African American male in May 1971. The fallout from the incident led to investigations of STRESS by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, forcing the DPD to publicly defend the undercover decoy program that critics accused of being a "murder squad" with a shoot-first mentality. The families of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell also played a key role in maintaining public pressure on STRESS by holding a joint funeral for their sons, demanding answers and justice from the authorities, and ultimately winning a $270,000 wrongful death settlement in a civil lawsuit against the Detroit Police Department .

The fatal shootings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell implicate law enforcement policies and procedures designed to legitimate state violence, beyond the question of the criminal guilt or innocence of a single police officer. The superficial investigation by the DPD Homicide Bureau failed to interview relevant civilian eyewitnesses and suppressed or declined to pursue evidence that contradicted the STRESS Team 4 unit's account. The Wayne County Prosecutor's Office did not conduct an independent and thorough fact-finding mission but instead rubber-stamped the cursory investigative report by the DPD Homicide Bureau. The actions of both law enforcement agencies gave every indication of being part of a broader de facto policy to reach a predetermined outcome of "justifiable homicide" every time a police officer used deadly force against a civilian 'in the line of duty,' no matter what the circumstances.

Even if every part of the encounter had happened exactly as Patrolman Worobec claimed--which is simply not possible, but even if?--why was it necessary to shoot two teenagers in the back as they fled the scene after dropping their alleged weapon (which turned out to be a badminton pole)? How possibly could an extrajudicial street execution be justified as public policy? The DPD's use of firearms regulations, made more permissive after the 1967 Uprising in order to preemptively 'justify' questionable actions by police officers, authorized shooting "persons known to have committed" felony crimes, including robbery and burglary, "when, in the sound discretion of the officer, it appears to be the only means of preventing the felon's escape." Michigan state law also, as Richard Worobec explained in justifying his actions, "says an officer may use a gun to detain a fleeing felon." Critics denounced this policy as a legal fig leaf that gave police officers a predetermined script to self-exonerate and granted them discretionary authority to commit murder and to execute civilians in the streets for alleged and unproved low-level crimes, in a state that did not even permit capital punishment through the judicial process. The deaths of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell also provided civil rights and black power activists with the evidence to argue that the Detroit Police Department had designed STRESS to terrorize the Black community through shoot-first policies of preemptive violence.

What Happened outside the North End Family Center?

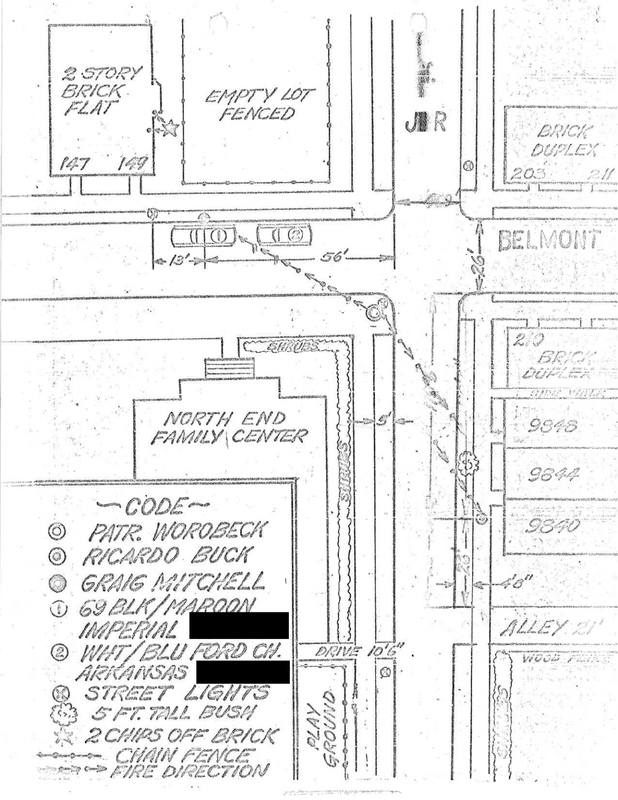

Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell died around 9:50 p.m. at the intersection of Belmont and John R, outside the North End Family Center, a neighborhood institution dedicated to Black self-empowerment and civic activism. The two boys were sitting on the steps and hanging out with friends when an apparently drunk white man staggered up, precipitating the encounter. Most of the accounts of the multiple African American youth who witnessed the fatal shootings of Ricardo and Craig cast doubt on the claims of self-defense against armed assailants made by Patrolman Richard Worobec, the decoy, and his partners in the undercover STRESS unit. The surviving teenagers, however, were afraid to go public with their stories out of presumed fear of retaliation by the police, and several refused to cooperate in the investigations by the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor, which they did not believe to be impartial.

Community activists documented police "surveillance and harassment" of Black youth from the neighborhood in the days and weeks after the shootings, evidence that these fears were very real. Barely a week earlier, two STRESS officers had killed a surviving witness (James Henderson) to a previous STRESS decoy killing in a likely premeditated murder, and the Labor Defense Coalition documented other acts of violence and intimidation against eyewitnesses in its 1972 conspiracy lawsuit against STRESS. (Law enforcement officials countered that the teenagers refused to cooperate because they were complicit in, or had witnessed, the criminal activities of Buck and Mitchell). The stories of the teenage eyewitnesses therefore come filtered through the community activists who operated the North End Family Center in an impoverished Black neighborhood just north of the downtown-midtown business corridor, and from additional fragmented and partial accounts available elsewhere in the archives.

It is impossible to know for certain exactly what happened in the deadly encounter on the evening of Sept. 17, 1971. These competing perspectives are compiled from media reports, firsthand and secondhand accounts, and especially the investigative files of the Detroit Police Department and the Wayne County Prosecutor. The available documents skew toward the state's perspective, and largely come from law enforcement investigations designed from the outset to exonerate the police, but they nevertheless contain contradictory information and revealing fragments that raise hard questions about--and in some instances repudiate--the official version of events. It is important to emphasize that the DPD and the prosecutor's office never intended for the investigative documents reproduced on this page to become public. Radical lawyers obtained the prosecutorial report justifying the fatal shootings, reproduced above and available un-redacted from the papers of Kenneth and Sheila Cockrel at Wayne State's Walter Reuther Library, through the discovery process of civil litigation. And 49 years after the incident, our Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab project (with the assistance of Professor David Goldberg of Wayne State University) obtained the DPD Homicide Bureau's 262-page investigative file of the deaths of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell through a Freedom of Information Act request and, in addition to the individual documents included on this page, have made the full file publicly available here (note: 167 MB).

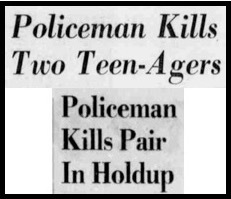

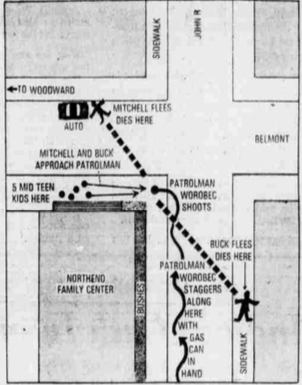

Initial Police and Media Reports: As always, the initial media reports in the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News portrayed the shootings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell through the framework provided by the DPD. "Detroit police said a STRESS officer shot and killed two teen-age boys," the first Free Press article began, "after they had attacked and robbed the officer and tried to flee." The DPD sources claimed that Patrolman Richard Worobec was pretending to be a drunk with car trouble, walking down the street with a gas can in his hand, when Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell "grabbed him and struck him repeatedly until he fell to the ground." Patrolman Richard Worobec then fired the shots in self-defense after carefully following protocol: "Worobec had identified himself as a police officer and had ordered the youth to halt after they knocked him down and took his wristwatch." The Detroit News reported the same story with a few more details, including that one of the Black youths said, "what's going on, brother?" to Worobec before they "threw him to the sidewalk." DPD sources told the News that Buck and Mitchell continued to beat Worobec with the metal rod, "despite his shouts that he was a policeman," and stole his watch before the officer fired all six shots from his revolver, killing both teenagers as they fled in two separate directions. The next day, after community members challenged these accounts, the DPD called a press conference and claimed that the two boys had attacked Worobec with "an 18-inch metal rod" (the police produced a badminton pole that the North End Family Center had discarded in the trash as the "weapon") and that the officer's watch had been found underneath Buck's body. The Detroit News created a graphic (at right) based on the crime scene sketch by Homicide detectives, further reinforcing the official story despite immediate challenges to its accuracy by community members who knew Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell and/or had witnessed the incident and its aftermath.

The Accounts of Black Teenage Witnesses

Benjamin Holloway, Sister Elizabeth Harris, and John Cosby: On September 18, the day after the incident, the leaders of the North End Family Center held a press conference to dispute the police account of the shootings on behalf of multiple Black youth who had been at the scene. The spokespersons were Benjamin Holloway, the director of the center, Sister Elizabeth Harris, a Catholic nun who worked there, and community activist John Cosby. The evening before, several dozen residents of the neighborhood had gathered at the North End Family Center for a spontaneous protest. The immediate consensus held that the shooting of the two youth had been "wanton murder" and impossible to justify since, even according to the official police version, Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell were fleeing from the officer and no longer armed when killed. The next day, the leaders of the North End Family Center sharpened this attack by labeling the official DPD account a fabrication, based on evidence given to them by several eyewitnesses who were afraid to come forward publicly. These witnesses were all African American teenagers and friends of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, who were both employed by the North End Family Center and also participants in its youth programming.

"Cold-Blooded Murder": According to the North End Family Center's press conference, the surviving youth who were on the steps that night had witnessed "cold-blooded murder." At least three anonymous Black teenagers stated that a white man who appeared to be extremely drunk staggered up to the intersection, and Buck and Mitchell stood up from the steps of the center to offer him assistance. Then "a tussle ensued with the white man ending up in the bushes. The white man came up shooting and another white man appeared from behind the bushes, shooting too. The second man shot Buck while Mitchell was being shot by the decoy," meaning Worobec.

The leaders of the North End Family Center later came to believe that they had made a strategic mistake in not publicly identifying these youth witnesses at the outset. According to a retrospective analysis by the center's investigator of the killings, "by trying to protect the witnesses we lost time--the truth of the situation should surface immediately." The analysis emphasized that this decision allowed the DPD to control the media narrative regarding what happened and enabled the Homicide Bureau and Wayne County Prosecutor investigations to discredit the civilian witnesses. The North End Family Center acknowledged that several of the teenage witnesses "did not at all times tell the truth" to law enforcement investigators, albeit for understandable reasons, including the center's own documented evidence that DPD officers harassed and intimidated youth witnesses and other Black residents of the North End neighborhood in the aftermath of the shootings.

Research Ethics Note: Our project has decided to maintain the anonymity of the youth witnesses who were juveniles (under age 18), unless and until we contact them or are contacted by them to receive permission. Although the FOIA file provided by the DPD redacted these youth's identifies, we have identified their names through other documents found in the archives. We are reluctant to reproduce the silences so often found in the state's archive, especially because of the strong evidence that their original requests for anonymity originated from fear of police retaliation, but have chosen to do so because they were juveniles at the time and have not provided their consent.

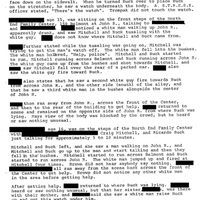

African American Teenage Eyewitnesses: The story told by the leaders of the North End Family Center on behalf of an unknown number of anonymous Black teenagers described two unprovoked murders by two different white police officers rather than acts of self-defense by Patrolman Richard Worobec alone. The names of most of these youth are redacted in the investigative files of the DPD Homicide investigation and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office, each of which sought to interrogate the frightened teenagers with the clear intention of discrediting them, rather then engaging in a neutral fact-finding inquiry. (Our project has located the names through a document acquired by attorneys involved in civil litigation against STRESS and identified them only by initials below). It is therefore important to emphasize that the stories that these youth told to law enforcement officials whom they did not trust, while under duress and in fear of police retaliation, were not necessarily the full or even the accurate versions of what they witnessed. The DPD and prosecutorial documents also portray the accounts of the youth eyewitnesses in the most negative light possible, including by criminalizing them as part of a group of "thugs" and emphasizing irrelevant information about prior encounters with law enforcement. And furthermore, there were at least two other African American teenagers on the steps of the North End Family Center that night who declined to come forward even anonymously. But even with these archival silences and distortions, the stories told by multiple youth witnesses clearly contradict the police account.

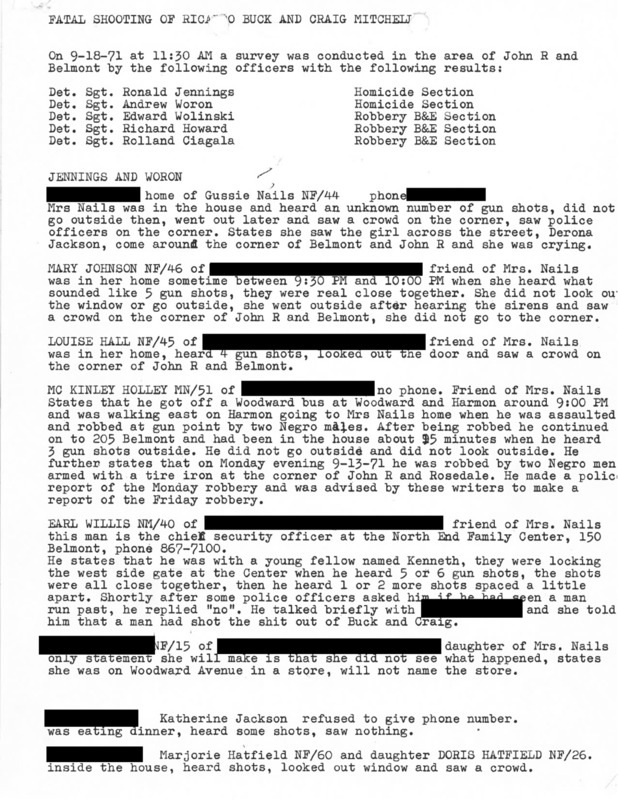

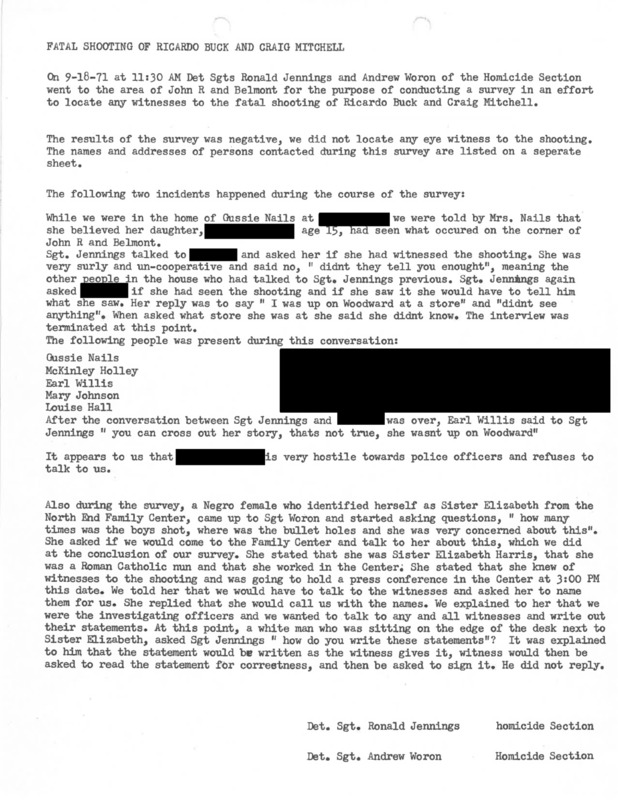

- LN, a 15-year-old African American female, told Homicide detectives in their initial canvass that she had not seen what happened and was instead a block away on Woodward Avenue in a store, which she refused to name. Her mother, however, told the detectives in a follow-up visit that her daughter had witnessed the shootings, and her friend MB also stated that LN was present. In a follow-up visit, LN again refused to tell the detectives anything, and their formal report described her as "very surly and un-cooperative" and "very hostile towards police officers" (gallery below, second from left). Investigators attributed her refusal to cooperate to her participation with Buck and Mitchell in criminal activity, but it is at least as plausible that she did not want to speak with law enforcement officers after watching their counterparts gun her friends down in the street.

- SM, a 15-year-old African American male, was not contacted by DPD Homicide Bureau investigators in their initial canvass but talked to law enforcement authorities at some point, presumably during the separate investigation by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office (right). Witness SM told investigators that he was hanging out with LN and MB on the steps of the North End Family Center when he "saw Mitchell and Buck tussling with the white guy." SM also stated that Craig Mitchell was trying to remove the white man's watch (note that the police claimed to find the watch under Ricardo Buck's body, not Mitchell's). Then, according to SM, the white man fell to the ground and yelled "help, police." Mitchell and Buck started running away, and the white man jumped up and fired at both of them. SM also insisted that a second white man fired at Ricardo Buck from the other side of John R Street (which is where the STRESS backup team was positioned).

- MB, a 16-year-old African American female, told the prosecutor's office (right) that she was sitting on the steps of the North End Family Center with Buck, Mitchell, SM, and LN when they saw the white man walking up the street. Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell walked up to him and started talking and then, after some sort of struggle, they began running away and the white man started firing a gun. Witness MB, along with LN and SM, ran away to get help. (They all said that they did not realize until later that the white man was a police officer, raising doubts about whether Worobec had really yelled 'halt, police' multiple times as he claimed).

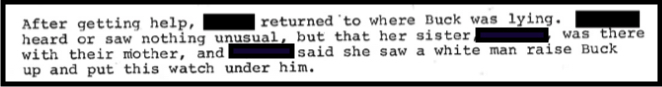

- RB, the younger sister of MB, returned to the scene with MB and their mother and said that "she saw a white man raise Buck up and put this watch under him." This account came secondhand from her sister MB, since investigators did not interview RB before the Wayne County prosecutor made the finding of "justifiable homicide."

Why did two law enforcement agencies not interview an eyewitness alleging a police coverup? It is suspicious, to say the least, that law enforcement officials did not seek firsthand evidence from RB, an eyewitness alleging that Richard Worobec framed Ricardo Buck by planting the watch under his body after his death. The "justifiable homicide" memo by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office did recommend taking RB's statement eventually, but only to "negate" the rumors spreading around the neighborhood that the police department had framed Buck and Mitchell.

A likely eyewitness account, 47 years later. The prosecutor's office also interviewed Gino Fortune, a 19-year-old African American youth, who claimed in his 1971 statement that he had been inside the North End Family Center when he heard gunshots and rushed outside. Fortune said that he saw several police officers searching in the bushes and one say, "Did you find my watch?" He also observed the officers searching for a weapon, and one finding a "little red rod about the size of a pencil." As with LN, Fortune's account that he was nearby but not an eyewitness to the actual shootings was dubious at the time, and he was a likely anonymous source for the summary provided by the leaders of the North End Family Center.

- "He lunged at Buck": In 2018, Gino Fortune told the Crimetown podcast that he had in fact been sitting with Buck and Mitchell on the steps of the North End Family Center when the incident began, after a game of basketball. The group had seen a white man staggering down John R, wearing a gold chain and nice watch, who "had no business in the neighborhood" and "was asking for" his jewelry to be stolen. Fortune said that he, along with Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, surrounded the apparently drunk white man and began asking him questions, but before they could do anything, "he lunged at Buck." After Worobec started it--"he just jumped on Buck"--the group then began to "beat him down." The white man then started yelling, "Police officer!" and suddenly "we see these white guys jumping out of the bushes and everywhere," with bullets flying. Fortune claimed that multiple police officers were shooting their guns, "like Vietnam out there," and he saw someone shoot Ricardo Buck as he tried to flee. Fortune also remembered that the undercover police were firing bullets at him as he ran into the center (there is no evidence of this in the archival record, which does not mean it didn't happen, but it is also important to assess Fortune's memories and account of what happened 48 years earlier with caution, in all respects).

Additional eyewitnesses disputing the police story: The Wayne County Prosecutor's Office also separately interviewed several youth from the neighborhood who were eyewitnesses to the shootings or their immediate aftermath and whose accounts contradicted or otherwise cast doubt upon the official police version.

- RJ, a 12-year-old African American female, told investigators that "she observed a white man standing over the body of Craig Mitchell and observed him fire a second shot at Mitchell from extremely close range." (Based on the layout of the incident, if the allegation was true, this man would have to have been a second shooter from the STRESS unit, not Patrolman Worobec. The prosecutor's inquiry discounted this possibility because Mitchell had only one gunshot wound, although the North End Family Center's investigator raised questions about the integrity of the coroner and Mitchell's autopsy report). Then, after Witness RJ and her sister DRJ walked over to where Ricardo Buck was lying dead in the street, she saw a white man "put his hand underneath Buck's body" [possibly to plant the watch, and possibly to look for it], although she did not "see anything in his hand."

- DRJ, a 14-year-old African American female, told investigators that she and her sister RJ heard the initial round of gunfire, ran out of their house, and saw a white man shoot a wounded Craig Mitchell as he was crawling on the ground on Belmont Street.

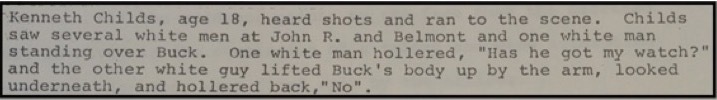

- Kenneth Childs, an 18-year-old African American male, told investigators that he saw several white men standing over Ricardo Buck's body, and one man yelled, "Has he got my watch?" and another man lifted up the body and responded, "No."

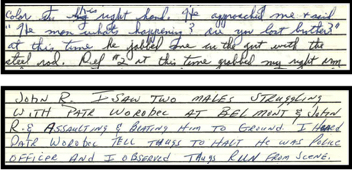

- JR, a 14-year-old African American male. The DPD canvass of the neighborhood also turned up a 14-year-old (identity redacted) who was walking on Belmont and "saw 4 shots" and then found Craig Mitchell's body laying under a car. The detective who conducted this interview did not appear to be interested in finding out any details about what this eyewitness had actually seen happen on the street that night (see document gallery below right).

The above accounts come from the combined files of the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor's office, both of which conducted investigations that could be described as perfunctory at best, and more accurately as predetermined and deliberately designed not to uncover any inconvenient truths about what really happened. The DPD Homicide Bureau completed its inquiry in a single day and made no attempt to track down potentially key witnesses who were not available or to conduct further investigation when contradictory evidence emerged. The Homicide Bureau did not include a single one of these African American youth in its official report on the results of its investigation for the prosecutor's office (analyzed below), silencing their perspectives and deliberately skewing the document to highlight the police officer witnesses whose accounts supported the version told by Patrolman Worobec.

The DPD's disinterest in conducting a substantive investigation extended even to witnesses whose accounts might have provided support for the version of events told by the STRESS team, indicating that the Homicide Bureau viewed the canvass as pro forma and did not anticipate the fierce protests that were soon to erupt (none of the previous eight STRESS decoy killings even made the newspapers). Several people contacted by investigators expressed fears of "the gang which hangs out on the corner of John R and Belmont," but the Homicide Bureau did not even try to determine if the "thugs" that a number of neighbors mentioned included Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell and their friends hanging out at the North End Family Center or referred to some other group entirely. The DPD investigators also talked to the father of Anthony Jankowski, an 18-year-old white male, who provided a thirdhand account that they made no effort to verify. As described by his father, Anthony ran out of their house at the sound of gunfire and saw Ricardo Buck lying on the ground. He ran into LN, who was "screaming her head off that they had shot Buck," and her younger sister DN, who said that Buck and Mitchell "did something to the man who was carrying a can of gas or oil. The man went down then came up shooting" (gallery below, second from right).

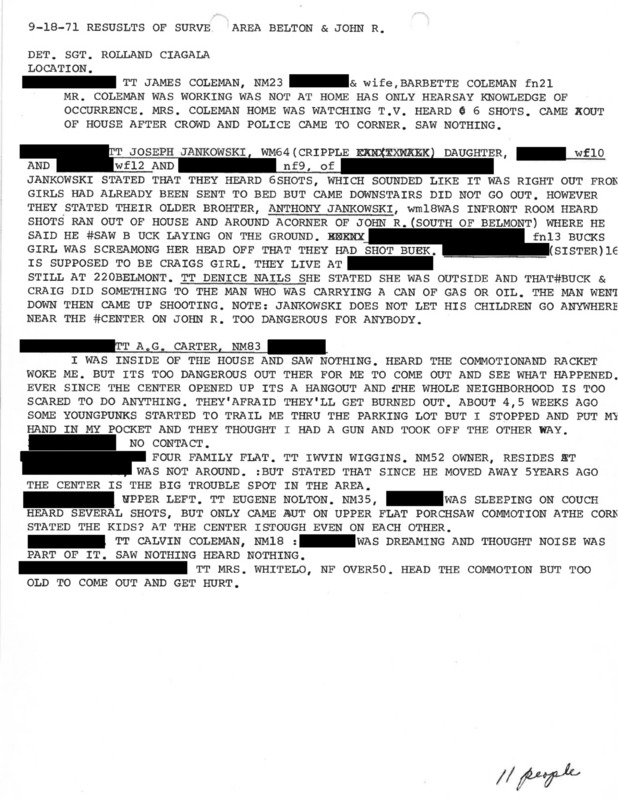

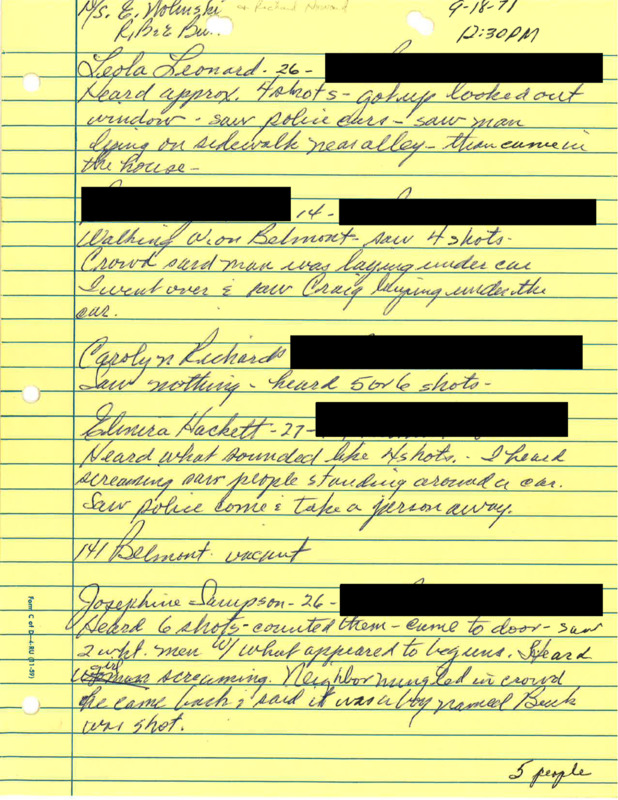

The gallery below contains four reports from neighborhood canvasses for witnesses by DPD detectives on the day after the shootings. (Many of the names are redacted by the city of Detroit as part of the legal rules governing disclosure of FOIA documents containing the identity of juveniles). This minimal inquiry was the extent of the effort made by the police department to test the versions of the encounter told by the STRESS unit, covered in the next section, with the accounts by the multiple teenagers from the North End neighborhood who either witnessed the killings of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, or the activities (included the alleged coverup) by police in the immediate aftermath, or both. The prosecutor's office also made little effort to chase down the leads and investigate the contradictory stories from these reports in making its routine finding of "justifiable homicide" in the fatal police shooting of two civilians.

The Versions of Police Officers on the Scene

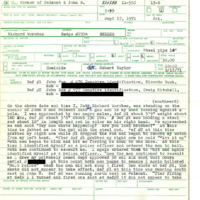

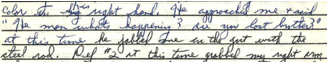

Richard Worobec gave his statement to the Homicide Bureau and then filed his initial incident report of a "felonious assault and robbery" (both at right) after the fatal shooting of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell on the evening of September 17, 1971. The STRESS decoy officer stated that he was "standing on the corner" of Belmont and John R, leaning against a light pole and holding a gas can, when "two negro males" accosted him and one said, "Hey man what's happening? Are you lost brother?" This speaker, later identified as Ricardo Buck, then "jabbed me in the gut with a steel rod" and stole his watch off his arm. According to Worobec, the two assailants "began to kick and hit me forcing me down to one knee." [Worobec reported no injuries from this alleged assault]. He identified himself as a police officer, but "both men continued to assault me." He then pulled out his .38 pistol and "both men began to escape." Worobec stated that he then yelled, "Halt Police," but they kept running. He fired two shots at defendant #1 [Ricardo Buck], who was running southeast down John R, but missed. He turned and fired two shots at defendant #2 [Craig Mitchell], who was fleeing northwest up Belmont. Then, Worobec claimed, he turned back and fired the final two bullets from his six-shooter at Ricardo Buck, who fell to the sidewalk bleeding badly.

Worobec stated that he then called for a police wagon to take defendant #1 [Ricardo Buck] to the hospital, and when the Scout 13-8 car arrived and placed him on the stretcher, the stolen watch fell from his body to the ground. Worobec also stated that he recovered the "steel rod" by the light pole at the site of the attack. He and a member of his STRESS backup, Patrolman John Mazzoni, then searched the scene and eventually found the body of Craig Mitchell underneath a car, after a crowd of civilians had gathered nearby.

It is notable that, in the hand-written statement to the Homicide Bureau, which Worobec made first, he switched pens from black to blue ink midway through the first page, right in the middle of a phrase that starts with "at this time" and continues with "he jabbed me in the gut with the steel rod." Given that the blue pen was not running out of ink, this switch in the middle of a sentence is curious and potentially revelatory. Since all of the STRESS officers on the scene went to the Homicide Bureau in the DPD's downtown headquarters together to give statements, it is probable that this indicates a moment when Patrolman Worobec stopped writing his account to confer with other officers, and perhaps also with Homicide Bureau detectives, before proceeding with the specifics of his claim that the two dead youth assaulted him with a weapon. As detailed below, Worobec's backup partner, Patrolman John Mazzoni, paused and switched pens at the exact same point in his own statement.

STRESS Backup Officers: The other three members of STRESS Team 4 gave the following accounts to Homicide detectives. It is crucial to emphasize that none of their initial reports mentioned seeing a watch under Ricardo Buck's body, and neither did any of the initial incident reports of the five additional squad car patrolmen who responded to the radio call of a shooting (discussed more in the section below). None of the STRESS backup officers mentioned seeing the "steel rod" weapon either--the aluminum badminton pole that the North End Family Center had thrown out in the trash that day, and that Patrolman Worobec produced as evidence of the assault when searching the scene after the attack. Patrolman Mazzoni and Patrolman Schaecher, the backup team on foot, also provided inconsistent accounts of their proximity to the encounter, changing their initial story to put them close enough to the alleged assault to have witnessed it, but maintaining that they were not near enough to have fired on Ricardo Buck from the bushes beside the North End center, as several teenage eyewitnesses insisted.

- Patrolman John Mazzoni, a member of STRESS Team 4, told the Homicide Bureau (below gallery, left) that he was walking north on John R with Patrolman Donald Schaecher as backup, observing the actions of undercover decoy officer Richard Worobec. Mazzoni said that he then "saw two males struggling with" Patrolman Worobec, "assaulting & beating him to the ground." Mazzoni claimed that Worobec ordered them to halt and identified himself as a police officer, and then "I observed thugs run from the scene." Mazzoni heard gunshots and saw Ricardo Buck, the "one N/M [Negro male] running east from Belmont & John R, fall to ground."

- Patrolman Donald Schaecher, a member of STRESS Team 4, told the Homicide Bureau (below gallery, second from right) that he was walking north on John R with Patrolman John Mazzoni when he saw "2/N/M approach . . . [and] assault and knock down" Patrolman Worobec. Schaecher said that Worobec yelled, "Halt, I'm a police officer," and then the defendants began running away and he heard several shots. He saw one defendant [Ricardo Buck] fall to the ground and went to search for the other defendant [Craig Mitchell] but could not find him. Schaecher then observed the Scout 13-8 wagon load the first defendant for the trip to the hospital.

- Patrolman Robert Bradford, Jr., a member of STRESS Team 4, told the Homicide Bureau (below gallery, right) that he was providing undercover backup as a Checker Cab driver when he heard [but did not see] about six shots fired and proceeded to find Patrolman Worobec standing at the intersection of John R and Belmont. Bradford saw a wounded "N/M laying on his stomach" and stayed at the scene until the police wagon, Scout 13-8, arrived to take this individual [Ricardo Buck] to the hospital. Brandford then went immediately to the Homicide Bureau to give a statement.

Did Worobec really fire toward his undercover backup team, or did either Mazzoni or Schaecher also shoot Ricardo Buck? Four days later, on Sept. 21, Patrolman John Mazzoni and Patrolman Donald Schaecher filed identical amendments to their original statement (below gallery, second and third from left) clarifying their location to be half a block away from the incident, walking north on John R between Belmont and Boston. This would have placed Mazzoni and Schaecher very close to the spot where Ricardo Buck was shot and killed--on the Homicide Bureau crime scene sketch at right, they would have been near the alley just south of the Buck marker on the sidewalk by 9840 John R. If the account by STRESS Team 4 is true, then Worobec would have fired--and missed--two shots at Ricardo Buck fleeing south on John R, then turned and fired two shots at Craig Mitchell fleeing west on Belmont, then turned back and fired two more shots in the known direction of his two backup partners, striking Buck twice with a revolver from an even greater distance than before.

This sequence of events is implausible. As detailed below, the autopsy report revealed that Buck was shot once from the front in the left chest and once in the lower right back, and the forensic evidence revealed that the two bullets found lodged in his body were of two different types. A real Homicide investigation would have asked two different questions and then run ballistics tests (and taken the non-police witness accounts seriously) to determine the answers:

- Did Patrolman Worobec fire the bullet that struck Ricardo Buck in the chest, before the youth started fleeing, as several of the anonymous eyewitnesses claimed?

- Did either Patrolman Mazzoni or Patrolman Schaecher fire one of the two different types of bullets that struck Ricardo Buck in the chest and in the back, as the youth presumably ran toward them to escape, rather than Officer Worobec firing from behind after killing Craig Mitchell in the opposite direction?

A meaningful inquiry would have noted that multiple witnesses gave accounts of more than one shooter firing at Ricardo Buck (see section above) and then asked whether it really made sense that Patrolmen Worobec, discharging a revolver in two different directions in the dark, missed with two shots at a fleeing Buck, turned in the opposite direction and fatally shot a fleeing Craig Mitchell, and then turned back around and accurately killed Ricardo Buck while he 1) was even farther away, 2) by shooting in the known direction of the location of his two backup partners on foot, and 3) with two different types of bullets that entered Buck's body from two different directions.

It is worth noting here that Richard Worobec himself portrayed his expert marksmanship in a notably different light for a Nov. 1971 Detroit News profile designed to tell his side of the story. Defending himself from accusations that he might have shot the boys in the legs, to stop them from escaping without killing them, Worobec said that he "fired purely on instinct" and "didn't aim at all." It is all the more remarkable, and obviously suspicious, that a police officer could fatally shoot two youth running down two different streets in the dark with a pistol when by his own account he "didn't aim."

Why did Mazzoni and Schaecher amend their location statements? Both of the STRESS backup officers stated in their initial statements that they were observing Worobec from a location on John R "between Belmont and Arden Park." Arden Park was two long city blocks (0.2 miles) away from the intersection of the encounter, and so this would likely have placed them about one block/one-tenth of a mile away, well below the crime scene depicted on the Homicide Bureau map at right. In the above left crime scene photograph, taken by a police photographer from their claimed original vantage point, the North End Family Center is not visible and the bushes are obstructing any clear view of the encounter. In short, it would have been difficult if not impossible for the two backup officers to have witnessed the alleged attack on decoy officer Worobec from this distance and at night. The statements amending their location placed Mazzoni and Schaecher within eyesight of the corner light pole that Worobec was allegedly leaning against when the purported muggers approached and robbed him. This makes Mazzoni and Schaecher more plausible eyewitnesses to the encounter between Worobec and the youth, although if there were a second shooter (see autopsy report section below), it also places them in the right location to have participated in the gunfire.

It is worth noting that both Mazzoni and Schaecher filed their identical amended statements (here and here) on the same yellow notepad that Detectives Wolinski and Howard used in their canvass of the neighborhood for witnesses (gallery above), also the same notepad that another officer, Michael Trompah, used to make a suspicious amendment to his initial statement as described in the section below. It is also noteworthy that STRESS commander James Bannon, in a news interview a few days after the shootings, defended Worobec's decision to open fire by stating that the backup officers had to follow him "as a distance where they could not be seen" and that in this operation, as was often the case, "covering officers temporarily lose sight of the decoy."

It is further curious, and suspicious, that Patrolman Mazzoni switched from black to blue pen in his hand-written statement to the Homicide Bureau (excerpt at right; full document below) at the exact same point in the events being recounted that Patrolman Richard Worobec did in his hand-written statement reproduced above. The pauses in both statements happened right before each officer recounted the alleged attack on Worobec by the two youth and strongly indicates that they stopped describing the incident in order to align their stories, around what appears very likely to have been a fabrication of the assault used to justify fatal force.

Why would Worobec have taken credit for two fatal shootings if he did not fire all of the shots? This question, which the Homicide Bureau never even considered despite the civilian witness testimony, requires informed speculation. It is possible that it made sense to STRESS Team 4 for the officer who was allegedly mugged in a "preemptive" decoy operation to be the one who took responsibility for both of the fatal shootings. If Mazzoni or Schaecher had fired at Buck while he ran toward them, no longer even allegedly armed, it would have raised questions under the "fleeing felon" policy of whether they could have apprehended him without shooting, which was permitted "if it appears to be the only means of preventing the felon's escape." It is also possible, indeed likely (see autopsy report section below), that Worobec initiated the confrontation, under the STRESS strategy of "proactive policing," when he saw a group of Black youth at night and presumed them to be criminals, and when Buck and Mitchell fled the undercover backup officers in STRESS Team 4 also opened fire in an ambush, as part of the unit's "shoot-first" philosophy of subduing the streets through state violence. It is quite conceivable, as some Black Power activists contended and as the forensic evidence that Buck was shot in the chest makes plausible, that Worobec initiated the confrontation by shooting Buck from the front as he approached the North End Family Center and then some combination of Worobec and his backup partners also fired at both youth as they ran away.

Read the initial and amended statements of the backup officers in STRESS Team 4 in the gallery below.

Censorship of STRESS Team 4 statements to the DPD's internal investigation. The four members of STRESS Team 4 also gave official written statements for the DPD's internal board of inquiry investigation (which was routine for officer-involved homicides) on September 27, ten days after the fatal shootings. On the advice of their DPOA union, each of the four officers invoked the Garrity exemption, an immunity provision from a 1967 Supreme Court decision that excluded statements compelled from police officers in internal affairs investigations from being used against them in a criminal proceeding.

Based on the Michigan legal code, the Law Department of the City of Detroit redacted these "Garrity statements" from the FOIA file of the DPD Homicide investigation provided to our project (see gallery below), part of the many deliberate silences in the historical record of police violence. (Documents from internal board of inquiries are also not available in the public record). While the redacted statements of the three backup officers are in the Homicide Bureau file, Patrolman Richard Worobec's internal investigation statement is missing entirely, which raises suspicions about when and why it was removed, what it contained, and whether it was materially different from his incident report and statement to Homicide investigators (both reproduced above). To be clear, this removal happened before--presumably long before--the FOIA request made by our project, because the Law Department would have redacted Worobec's statement like the other three had it been present in the internal police archives. Worobec's Garrity exemption claim, preceding the missing statement, is also in the gallery below.

The Watch: Evidence of Armed Robbery, or Police Framing and Coverup?

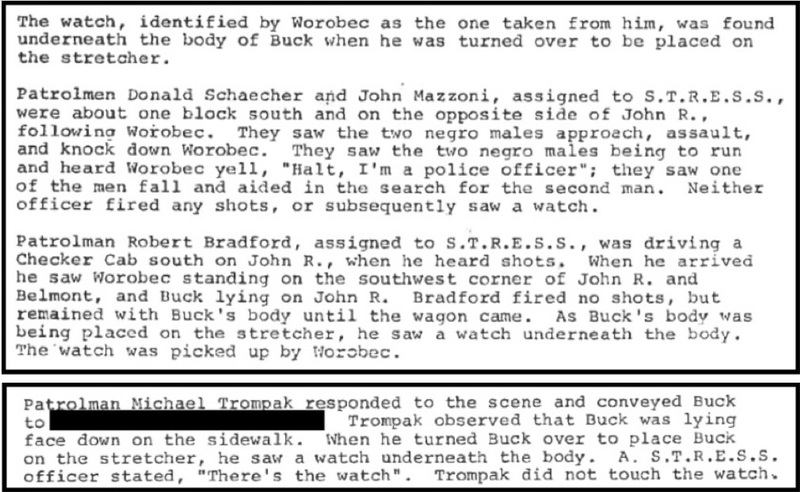

None of the three backup members of STRESS Team 4--John Mazzoni, Donald Schaecher, and Robert Bradford--corroborated Patrolman Worobec's account by mentioning a watch under Ricardo Buck's body in their initial statements to the Homicide Bureau (gallery above). Neither did any of the initial statements filed by five other police officers who responded to the scene in the immediate aftermath of the fatal shootings.

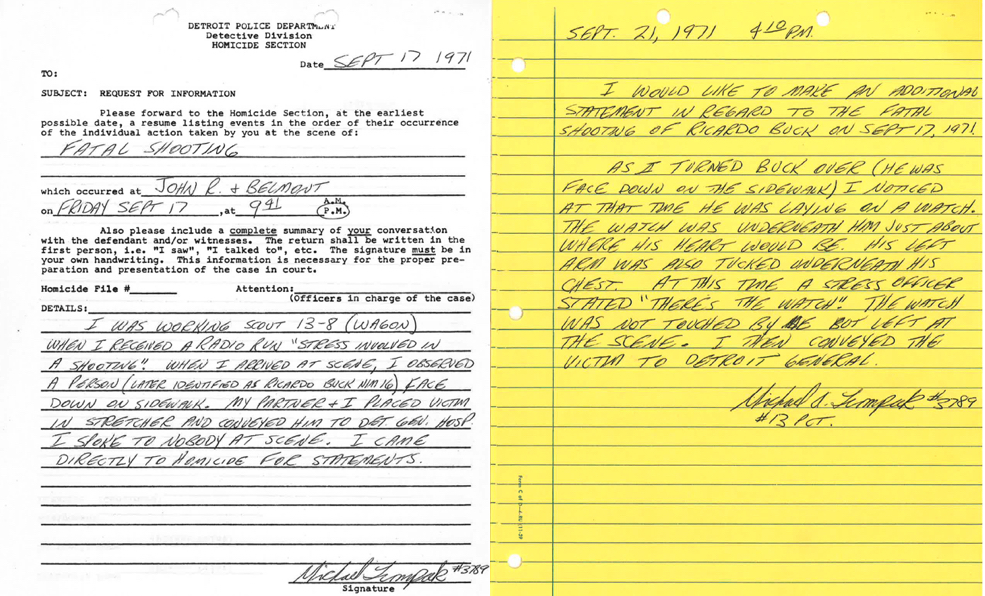

Patrolman Michael Trompah and Patrolman Robert Lynch were the two officers in Scout 13-8, a wagon car designed for prisoner transport. They responded to the scene about two minutes after Patrolman Worobec's radio call of a STRESS shooting and loaded Ricardo Buck on a stretcher to take him to the hospital. Both officers gave statements to the DPD Homicide Bureau almost immediately after the hospital run. Neither of the initial statements by Robert Lynch (left) or Michael Trompah (below left) mentioned the watch that Patrolman Worobec claimed dropped to the ground when the two men from Scout 13-8 put Ricardo Buck on the stretcher.

There is also no mention of a watch in the initial statement by Patrolman Robert Bradford (right), a member of STRESS Team 4 who later claimed, according to the Wayne County Prosecutor memo (excerpt below right), to have seen a watch underneath Ricardo Buck's body when Lynch and Trompah loaded him onto the stretcher. It is notable that the final report by the DPD Homicide Bureau (reproduced in the next section) does not mention that Patrolman Bradford saw a watch, and there is no evidence of such an account in the FOIA file, so the backup officer presumably added this information in a statement made directly to the prosecutor's inquiry.

The statements by Patrolmen Lynch and Trompah do not even mention the presence of Richard Worobec at the intersection of John R and Belmont, where they arrived and then quickly left. Patrolman Lynch's statement said that he "did not talk to anyone at the scene." Patrolman Trompah's initial statement also said he "spoke to no one at the scene."

The statements of Patrolmen Tromah and Lynch are dubious beyond the issue of the allegedly stolen watch. In addition to the members of STRESS Team 4, there were at least three other police officers who responded to Worobec's radio call and were present when Trompah and Lynch loaded Ricardo Buck into the wagon car: Andrew French, Fred Thorp, and Herbert Theibert. It is highly doubtful that these patrolmen did not speak to one another at a crime scene with at least nine police officers present. Several of the Black teenagers in the crowd of civilians that gathered recounted ample discussion among these white officers, including urgent discussion of where the watch might be and an allegation that one of the officers planted the evidence on Ricardo Buck. It is further crucial to emphasize that none of these other three squad car patrolmen listed as witnesses in the official DPD Homicide Bureau report--French, Thorp, and Theibert--mentioned seeing a watch in their statements contained in the FOIA file.

Four days later, Patrolman Michael Trompah submitted an additional statement (below right) claiming that he had seen a watch under Ricardo Buck's body when turning him over to load him onto the stretcher. Trompah also quoted an unnamed STRESS officer [Worobec] saying, "there's the watch." The DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office (right) considered Trompah's witnessing of the watch under Buck's body to be key evidence confirming Worobec's account and cited it prominently without any mention of its mysterious absence from Trompah's initial report. The same was the case with Patrolman Bradford, with the prosecutorial memo highlighting his eyewitness account of Worobec's discovery of the watch without asking why Bradford did not include this key information in his initial statement to Homicide.

It is highly suspicious, to say the least, that Patrolman Trompah and Patrolman Bradford submitted amendments to their original statements that just happened to confirm the immediate account given by the acknowledged shooter, Patrolman Richard Worobec, but neither considered it relevant to mention the presence of the stolen watch in their initial versions of what they saw that night. (Unlike Patrolman Mazzoni, the STRESS backup officer who clearly collaborated with Worobec as both men gave their statements, Trompah and Bradford arrived at the Homicide Bureau later because of their hospital run). The timing of Patrolman Trompah's additional statement is especially revealing, because it came only after the outpouring of protests and condemnation from Black organizations raised challenges to the police version and made clear that the Buck and Mitchell investigation would be scrutinized much more closely than previous STRESS killings. It also came only after the Homicide Bureau had gathered the accounts of three African American youth witnesses, detailed in the section above, who described several white officers standing around Ricardo Buck's body discussing the absence of the alleged watch and other implications that a white man had planted the evidence.

The alleged presence of the stolen watch, cited in Patrolman Worobec's initial statement, and four days later in Patrolman Trompah's convenient amendment to his version of events, provided the DPD Homicide Bureau and Wayne County Prosecutor's Office with physical evidence to back up the word of the decoy officer who claimed to have shot two muggers in self-defense.

It is also notable that Patrolman Trompah provided his additional hand-written statement on the same yellow notebook pad that Patrolman John Mazzoni and Patrolman Donald Schaecher used to submit their additional hand-written statements clarifying their location during the incident (this is clear from the "Form C of D" mark at the bottom left of all three pages). All three officers also submitted their additional statements on the same date, September 21. This arguably indicates that detectives in the homicide investigation solicited the three additional statements as part of a clean-up operation to reconcile the various officer accounts and provide eyewitness evidence for Richard Worobec's version of events.

Compare Patrolman Trompah's initial and additional statements below.

The Autopsy Mystery: Who Shot Ricardo Buck in the Chest?

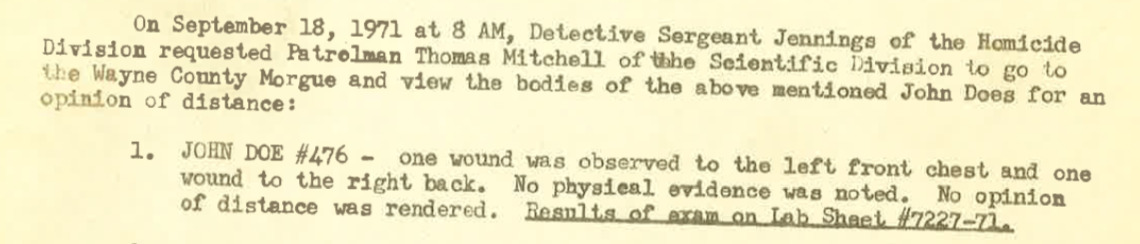

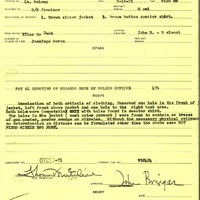

The DPD Homicide Bureau's investigative report listed as witnesses the medical examiner who conducted the autopsies on Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, the family members who identified their bodies, and the police officers from the Scientific Section who evaluated the forensic evidence. The Homicide Report, discussed in the next section, did not make any note at all of two significant discrepancies between the physical evidence and the incident accounts of Patrolman Worobec and the rest of STRESS Team 4. The police version, presented as undisputed fact by the Homicide Bureau report, held that Worobec alone shot Craig Mitchell in the back and then turned in the other direction and shot Ricardo Buck twice from behind, at distance, as he fled the scene of the alleged attack. The forensic evidence proves that this version of events did not happen, because Ricardo Buck was struck by two different types of bullets and, most important of all, suffered a gunshot wound from the front, in the chest.

Gunshot Wounds Incompatible with the Police Account: The investigative file of the DPD Homicide Bureau, obtained in 2020 through a Freedom of Information Act request, contains numerous documents revealing that Ricardo Buck died from two gunshot wounds, a shot from the front to the left side of the chest and a shot from behind to the right side of the back. The forensic evidence also revealed that the .38 caliber bullets were of two different types, one lead and the other a metal jacket.

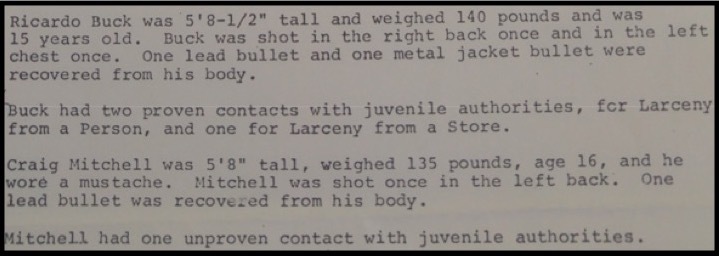

The autopsy of Ricardo Buck (right) was performed by Dr. Gilbert Corrigan, the Wayne County Medical Examiner. Corrigan found that the first gunshot caused an "entry wound of the left anterior central precordial chest," three inches from the center of the body, and then passed through the heart and lungs. The second gunshot "consists of an entry in the right posterior back," three and a half inches from the spine. Both bullets remained lodged in Buck's body. (Corrigan also performed the autopsy of Craig Mitchell, which found a single gunshot that entered the lower left back).

There is complete agreement in the available documents that Ricardo Buck's body had two gunshot entry wounds, one in the middle of the chest on the left side and the other in the lower right back. The Homicide Bureau's investigative file includes corroboration from the witness identification at the morgue by Ricardo Buck's grandmother, noting "gunshot wound to back and gunshot wound to chest," from a series of photographs that are redacted but clearly identified in the evidence list, from forensic evidence of the clothing of the deceased youth, and from other evidence analysis by members of the DPD's Scientific Bureau (see gallery below).

Two Plausible Scenarios. There are only two plausible scenarios to explain how Ricardo Buck died with a bullet wound in his chest.

- Scenario #1: Patrolman Richard Worobec shot Ricardo Buck in the chest in the initial encounter near the steps of the North End Family Center, as the teenage eyewitnesses claimed, before the youth started running away. This scenario not only fits with the forensic evidence, but it also fits with the broader pattern of STRESS decoy shootings during 1971-1972 in which officers claimed to have shot fleeing suspects in the back, but physical evidence and witness testimony proved that the officers had actually instigated the encounters and shot their victims from the front, often at close range and without provocation. For all three reasons--teenage witnesses, autopsy report, STRESS modus operandi--this is the most likely scenario.

- Scenario #2: One of the backup officers, either Patrolman Mazzoni or Patrolman Schaecher, shot Ricardo Buck in the chest as he ran toward them trying to escape, likely after Worobec had already shot him in the back. It is worth noting here that the teenage witnesses claimed that the backup officers had jumped out of the bushes by the North End Family Center immediately and started firing, contrary to their shifting claims that they had been much farther away, either half a block or a full block, when the incident occurred.

In either scenario, the three members of STRESS Team 4 who were on foot ambushed Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell, rather than the official police version that Patrolman Worobec was a vulnerable decoy far from his backup team when he miraculously shot two youth who attacked him at distance as they ran in two different directions.

Two Different Types of Bullets: The Scientific Bureau also found that the bullets in Ricardo Buck's body were of two different types--a lead bullet and a metal jacket bullet (below gallery, right). The Scientific Bureau's firearms analyst test-fired Patrolman Worobec's gun and concluded that both bullets had come from the same .38 Colt pistol, which was a personal weapon (as allowed by DPD policy) rather than a department-issued revolver. It is unlikely that the DPD's Scientific Bureau had the expertise to make this determination with precision, not least because the firearms "expert" was just a regular patrolman. A more thorough Homicide investigation would have requested testing by the Michigan State Police or FBI crime labs. The Scientific Bureau also never examined the guns of other members of STRESS Team 4 to see if they had been fired that night, in spite of the forensic evidence and accounts of civilian eyewitnesses that there had been more than one shooter.

Neither the DPD Homicide Bureau nor the Wayne County Prosecutor's investigation, examined next, raised any questions about how Patrolman Worobec could have shot Ricardo Buck once in the front left chest and once in the lower right back while firing from behind as the 15-year-old youth fled the scene on foot. Both law enforcement agencies showcased the accounts of Worobec and the rest of STRESS Team 4, briefly noted the findings from the autopsy report, and left it at that.

Conclusion: The STRESS Officers Lied. Based on the police depiction of the crime scene, itself based on Worobec's statement, the bullet wounds in both the front and back of Ricardo Buck's body do not make sense. The DPD's Scientific Bureau found that the distance from which the shots were fired could not be determined, except that they were each from more than two feet away. There's little debate that the officers in STRESS Team 4 lied. The question is how and why. What scenarios might explain these bullet holes?

Revisiting the Plausible and Implausible Scenarios.The most likely scenario is that Patrolman Worobec shot Ricardo Buck in the chest first and then covered it up. Then the relevant question becomes: did Worobec or other officers kill Buck and Mitchell without provocation, which would mean either a murder or manslaughter scenario, or did the two youth instigate the encounter by mugging the decoy officer, requiring self-defense?

- Scenario #1a. Patrolman Worobec instigated the encounter without provocation and shot Ricardo Buck in the chest, causing both youth to flee. Then some combination of Worobec and the backup officers shot both of them dead. This is the version told by Benjamin Holloway and Sister Elizabeth of the North End Family Center, on behalf of the young Black eyewitnesses who were too afraid to come forward. In this version, Patrolman Worobec began firing, unprovoked, at Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell before they had a chance to do anything, regardless of their intent. Then other plainclothes officers burst out of the bushes, also firing.

- Scenario 1b. Patrolman Worobec shot Ricardo Buck in the chest after the two youth attacked him, but then lied about it and said he shot both youth as they fled. While this is theoretically possible, if the youth really had attacked Patrolman Worobec with a weapon and beaten and kicked him, and his backup team really had witnessed this felony assault, why would STRESS Team 4 fabricate an alternative self-defense scenario? The prosecutor definitely would have "justified" the shooting if the decoy officer had fired on his assailants in the chest or the back.

- Scenario 2. Patrolman Mazzoni or Patrolman Schecher of the backup team shot Ricardo Buck in the chest as he fled toward them, and then STRESS Team 4 conspired to cover it up, perhaps because Buck was unarmed and could have been captured without fatal force.

- Scenario 3. Multiple officers fired at the teenagers. Perhaps Worobec shot Buck in the chest first, then both boys ran, and Worobec shot at least one of them from behind. This could explain why Ricardo Buck had gunshot wounds from two different directions, even if both came from Worobec's gun, loaded with two different types of .38 bullets. Or perhaps Ricardo Buck was caught in a crossfire, between Worobec and his backup team.

- Scenario 4. For Worobec's account to be truthful, his first accurate shot at distance--after he shot and killed Craig Mitchell in the other direction--would have had to strike the fleeing Ricardo Buck in the back, spinning him around, and then his second accurate shot could have entered Buck's chest from the front. It is difficult to imagine a jury believing this story, if the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor had weighed the case impartially and pursued either a grand jury inquiry or arrest and prosecution.

The Homicide Bureau Covered Up and Contributed to the Lies. There is strong evidence from the official autopsy report itself that the scene could not have unfolded as the STRESS officers and the DPD Homicide Bureau investigators, examined next, insisted that it had. While what definitively happened is not ultimately unknowable, what is certain is that the Homicide investigation did not even try to ask hard questions, did not even try to reconcile the location of the bullet holes with its depiction of the crime scene, did not even try to test the guns of the other officers to see if they had been fired, did not even try to evaluate the account of the police officers objectively, and did not even try to find out if the alternative accounts of multiple Black youth witnesses had any merit.

The gallery below contains some of the extensive physical evidence in the DPD Homicide Bureau file showing the direction of the bullet wounds and the bullet types that struck Ricardo Buck in the chest and back.

Alberta Wilburn, Ricardo's grandmother, identified the body at the morgue and noted gunshot wounds to chest and back

Photograph log from Wayne County morgue showing chest and back wounds in Ricardo Buck's body (images redacted in FOIA file)

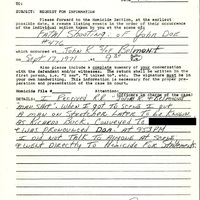

The Homicide Bureau Investigation: A Predetermined Outcome

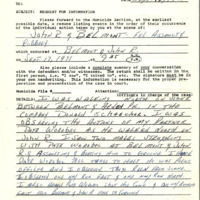

The DPD Homicide Bureau conducted a rapid and incomplete investigation designed to confirm Patrolman Worobec's version of events. On September 21, four days after the fatal shootings, the Homicide Bureau sent its four-page report (right) and supplemental documents to the Wayne County Prosecutor. Following protocol, the Homicide report took the form of a "request for warrant recommendation," which was supposed to present all of the factual evidence in a neutral way, to enable the prosecutor's office to make an independent assessment of whether to bring criminal charges or make a finding of "justifiable homicide." The report was instead a biased, one-sided, and incomplete document. At best, the Homicide Bureau clearly intended its report to predetermine the outcome by suppressing inconvenient and contrary evidence in favor of the Worobec's account. At worst and more likely, the evidence strongly suggests that its detectives--and the Detroit Police Department hierarchy in its stonewalling of subsequent external investigations--were complicit in framing Ricardo Buck for the allegedly stolen watch and covering up the unjustified shootings of Buck and Craig Mitchell.

The Homicide Bureau's investigative report listed 10 relevant witnesses from the crime scene and its immediate aftermath, and all were police officers. The final report listed none of the African American teenagers identified in the police canvass of the neighborhood (the accounts of at least eight youth emerged over the course of the investigation). As detailed above, the Homicide detectives made little effort to track down key civilian eyewitnesses and made no effort at all to pursue the leads that any of the Black youth provided that challenged or contradicted the statements of Patrolman Worobec and the rest of STRESS Team 4. It is fair to say that the Homicide investigation proceeded on the explicit presumption that accounts provided by white police officers automatically outweighed and completely eclipsed any and all contrary evidence by Black civilians who witnessed the events.

The report that the Homicide Bureau send to the Wayne County Prosecutor therefore presented Patrolman Richard Worobec's account as the true version of events, without any questions or doubt. In this story, Buck and Mitchell attacked the decoy officer, unprovoked, beating and kicking him and stealing his watch. Worobec, operating by the book (to a level suspiciously presented as an idealized version of officer training), twice identified himself as a police officer, then yelled "Halt, police," and did not make the decision to fire his gun until "both continued to run." The Homicide Bureau emphasized that Patrolman Mazzoni and Patrolman Schaecher, the STRESS backup on foot, both witnessed the assault, heard Worobec identify himself as a police officer and tell the two "Negro males" to halt, and saw the fatal shots that hit Ricardo Buck, who fell to the ground on John R near their location.

The Homicide Bureau investigation made no effort to determine if there was any physical evidence that Patrolman Worobec had suffered any wounds from the alleged beating and kicking that he received from the two assailants. The investigative file contains no hospital records or photographic or other documentary evidence of any injures to Richard Worobec, almost certainly because he had not been injured, or he would have included that in his report. This failure by Homicide detectives to ask elementary questions about physical injuries to the alleged victim indicates either extreme incompetence or additional circumstantial evidence of a police coverup.

The Homicide Bureau report also did not mention that on September 21, the same day of its submission to the prosecutor, Mazzoni and Schaecher provided almost identical amended statements placing them at a location from which they actually could have witnessed what they claimed to have seen, unlike their vantage point from the location cited in their initial statements (see above). The investigative report also highlighted the statement of Patrolman Michael Trompah, who claimed that he saw the watch under Buck's body when loading him into the wagon car, without noting that this was actually an amendment to Trompah's initial statement, also solicited by the same DPD detective on the same day that Homicide secured the Mazzoni and Schaecher amendments and finalized the investigation.

And on top of all this, the Homicide Bureau investigative file did not even try to address how Ricardo Buck could have had a bullet in the chest if the accounts of Patrolman Worobec and the rest of STRESS Team 4 were truthful. This smoking gun is the most compelling evidence that the fatal shooting of Ricardo Buck could not have happened as the STRESS team claimed and that the Homicide Bureau participated in the coverup.

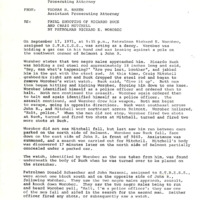

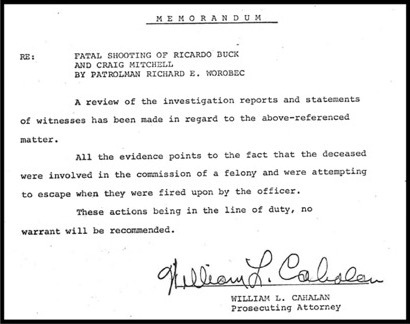

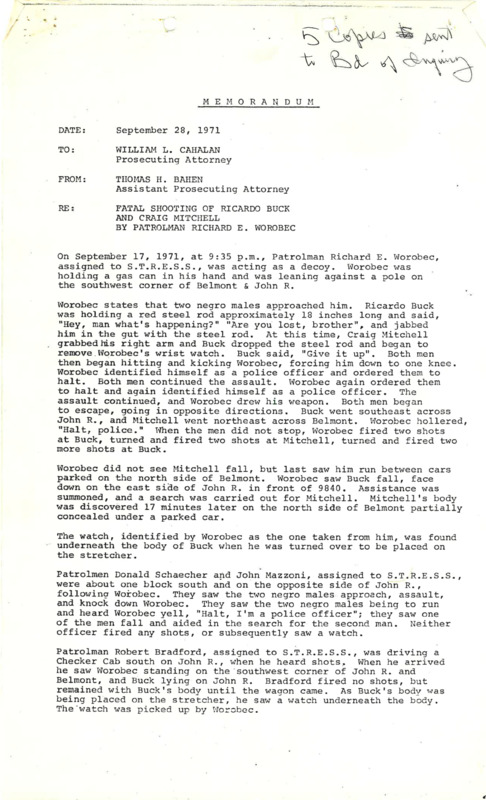

Wayne County Prosecutor: "Justifiable Homicide" of "Escaping Felons"

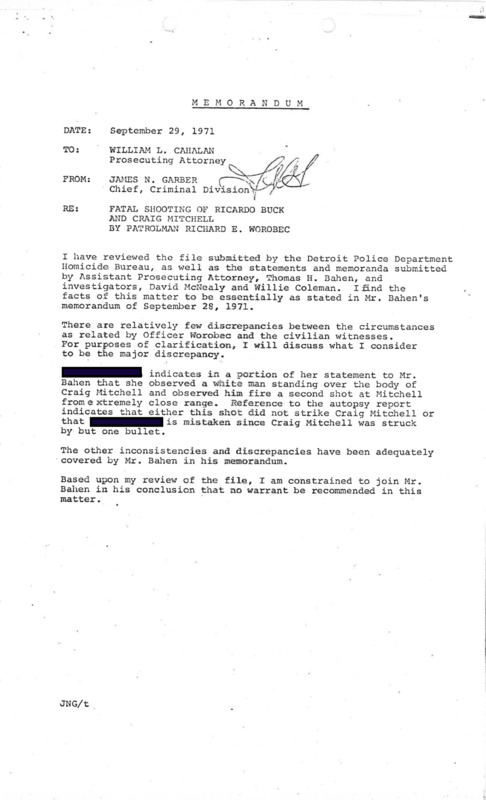

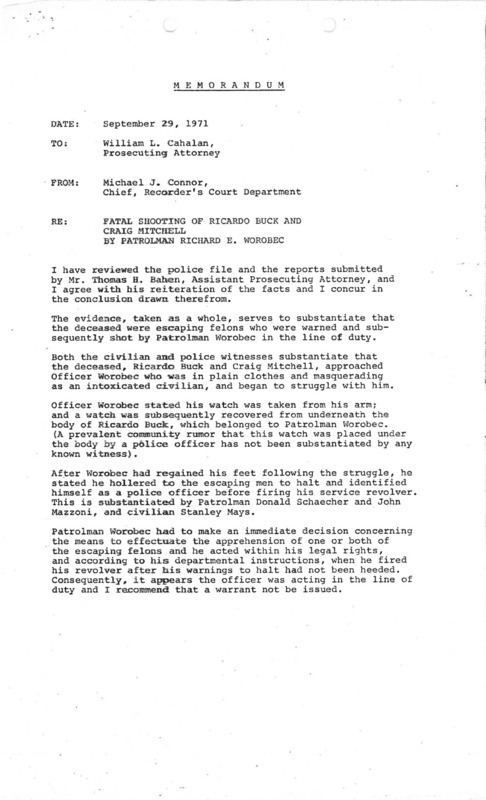

The Wayne County Prosecutor's Office received the investigative report from the DPD Homicide Bureau on September 21, conducted a further evaluation of the evidence, and announced its exoneration of Patrolman Worobec a week later, on September 28. Thomas Bahen, the assisting prosecuting attorney, led this process and was responsible for assessing all of the evidence and making a recommendation to Prosecutor William Cahalan on whether or not to bring criminal charges against Patrolman Richard Worobec for the homicides of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell. Unlike the DPD Homicide Bureau, the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office did conduct a substantive analysis of the contrary eyewitness accounts of some--although not all--of the Black youth who had been on the scene. Cahalan, who was routinely accused by Black activists of a "consistent pattern of prosecutorial whitewash" in police-involved homicides, assigned an interracial team of assistant prosecutors to work on the Worobec investigation, in recognition of the sensitive political nature of a case that had inspired protests in the streets and demands for abolition of STRESS. But just like the Homicide Bureau, the law enforcement officials who ran the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office approached the inquiry through the standard operating procedure that police officers had broad discretionary authority to use deadly force and the presumption that their accounts were truthful, whereas countervailing evidence from civilian witnesses should be disproved or ignored rather than given equal weight.

Presenting Officer Testimony as the Only Truth. The investigative report by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office, reproduced in full in the gallery below, began with the account provided by Patrolman Worobec (right). Like the DPD Homicide Bureau, the prosecutor's narrative portrayed an officer who found himself under attack with a "steel rod"--a deliberately prejudical way to describe an aluminum badminton pole that Buck and Mitchell likely never even wielded. The narrative then depicted an officer who carefully followed protocol by identifying himself twice and then twice commanding the two youth to halt before he used deadly force to prevent their escape. These details were crucial to building a case for "justifiable homicide" based on the fleeing felon provision in state law and the checklist of "use of force" procedures in the DPD manual. (In contrast, Worobec told the Detroit News that he "didn't aim at all" and "fired purely on instinct," which does not sound like a description of an officer calmly and carefully following a procedural checklist). The prosecutor's memo then asserted as uncontested fact that Worobec's watch had been found underneath Buck's body when loaded onto the stretcher, completely ignoring the significant red flags in the Homicide Bureau file itself about whether this was what really happened rather than a clean-up operation to retroactively make the shootings seem justified.

The prosecutorial memo, just like the Homicide Bureau report, did not even try to explain how Ricardo Buck could have a bullet in the chest if Patrolman Worobec shot the fleeing youth from behind--indeed did not even address this evidence but instead suppressed it entirely.

The prosecutorial memo then validated Worobec's version of events by highlighting the statements by the STRESS backup officers who allegedly witnessed the assault, and the claims by Patrolman Bradford and Patrolman Trompah to have seen the watch underneath Buck's body. These statements, reproduced and analyzed in the above section about the version of police officers on the scene, presented a uniform story by the police officers present for the shooting and its immediate aftermath. The prosecutor's office did not mention that two of these officers had amended their initial statements to make their location more favorable to Worobec's account, and that two of them had amended their initial statements after 'remembering' that they had seen a watch when Buck's body was loaded onto the stretcher, conveniently affirming Worobec's claim that the youth robbed him before he fired. The prosecutor's failure, or disinclination, to critically assess the shifting stories told by the white police officers contrasted sharply with the rigorous and skeptical stance toward the Black youth witnesses.

Discounting Civilian Witnesses: Next, the prosecutor's memo presented the accounts of Witness SM and Witness MB, two of the African American teenagers sitting on the steps with Buck and Mitchell that night. The prosecutor's office re-interviewed both youth, whose accounts to law enforcement (detailed in the second section above) described a murky struggle of unclear origin between their two friends and a white man whom they did not realize was an undercover officer. Witness SM also reported that a second white man fired shots from the bushes outside the North End Family Center, a possibility that the prosecutor's office did not pursue even though it fit with the crime scene layout and forensic evidence from the autopsy report. The memo further discredited Witness MB by noting that she was Craig Mitchell's girlfriend.

The Wayne County prosecutor did not even try to interview MB's sister RB, who reportedly saw a white man plant the watch under Ricardo Buck, and also did not interview LN, who refused to talk to police and was almost certainly on the steps that night. The memo relegated the accounts of four other Black youth to an addendum and did not consider them relevant, even though they raised further questions about whether there was more than one shooter and whether Worobec framed Ricardo Buck by planting the watch.

Criminalizing the Victims: The Wayne County prosecutor's report emphasized the juvenile records of Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell to provide additional reinforcement for Worobec's claims that they had attacked and robbed him. These findings were based on the DPD investigation, which spent far more time trying to dig up dirt on the two teenage boys than it did seeking to uncover the eyewitness evidence from their friends and neighbors. The FOIA file contains dozens of pages from their juvenile police records, a window into the everyday racial criminalization of African American youth growing up in a poor and segregated Detroit neighborhood.

Ricardo Buck's "two proven contacts" with juvenile authorities involved shoplifting and petty theft, not a violent assault against a person as alleged by Patrolman Worobec. The "larceny from a store" charge happened when he was 11 years old and, with a couple of other boys, shoplifted two pairs of pants valued at $13.98, which he admitted when brought to the juvenile authorities by his mother. The "larceny from a person" allegation was from a more recent incident when Ricardo and two other youth, purportedly including LN (who was at the homicide scene and refused to give a statement), took a purse that a woman had left in an office building.

Craig Mitchell's "one unproven contact" was completely irrelevant to the case except as it indicated the pervasive racial profiling and criminalization suffered by African American teenage males in the city of Detroit. According to the DPD Homicide Bureau file, Craig had two and not one documented encounter with law enforcement. In the fall of 1970, police officers detained Mitchell and five other African American teenagers as suspects in a rape investigation, based on no evidence other than their race, gender, and presence in the general area of the crime. The boys were innocent and eventually released, but the encounter stayed on their juvenile records. Then in the summer of 1971, a squad car detained Mitchell while he was walking with friends down Woodward Avenue on suspicion of carrying a gun under his shirt, but the object turned out to be a cigarette lighter. This racial profiling encounter also stayed on his juvenile record.

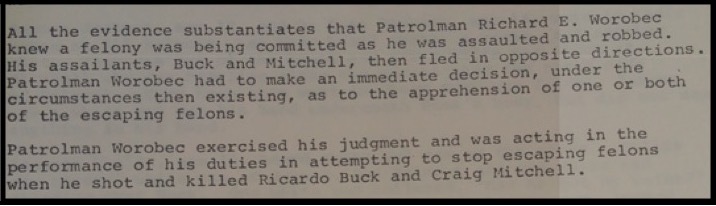

Exoneration and "Escaping Felons": Thomas Bahen, the assistant prosecutor, concluded the investigative report by stating that "all of the evidence substantiates" the account of Patrolman Worobec. This is a curious and clearly distorted formulation, given that the accounts of multiple civilian witnesses contained in the assistant prosecutor's own memo did not substantiate Worobec's story, and several Black youth that the prosecutor's office did not interview may well have contradicted it even more directly. The Homicide Bureau's file, as examined in detail on this page, also contained significant evidence that did not clearly "substantiate" Worobec's account, in particular the questions of why no other officer on the scene initiallly coorborated his story about the stolen watch and how Ricardo Buck suffered a gunshot wound in the chest from a shooter who fired from behind.

The prosecutorial investigation found that Patrolman Worobec had to make a split-second decision about how to apprehend the "escaping felons" who attacked and robbed him, and that under the discretionary authority delegated by state law, the officer "exercised his judgment and was acting in the performance of his duties in attempting to stop escaping felons when he shot and killed Ricardo Buck and Craig Mitchell."

Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan approved the recommendations and announced his findings on September 29, twelve days after the incident. The prosecutor's decision meant that the fatal shootings of the two unarmed and fleeing teenage boys by Richard Worobec were "justifiable homicides."

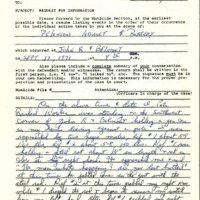

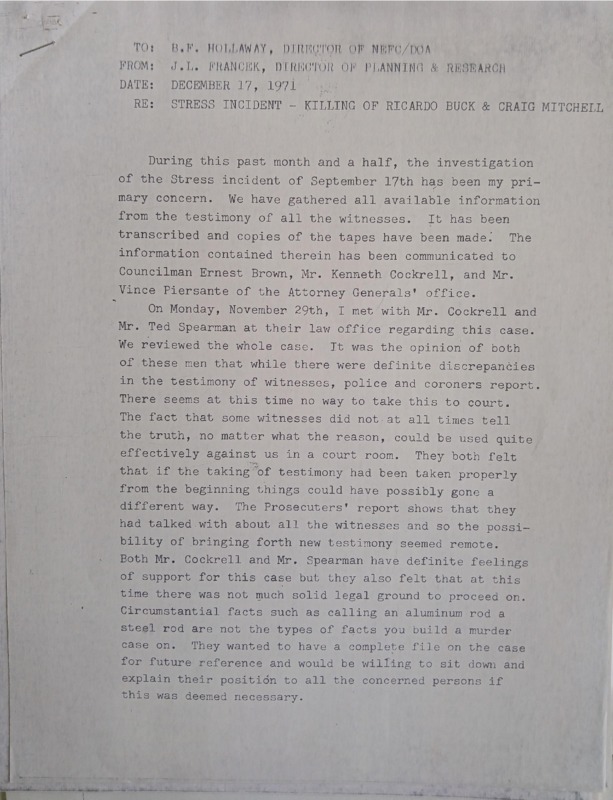

The gallery below contains the full investigative report by the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office and two additional documents from the prosecutorial investigation discounting the civilian accounts and endorsing the finding of "justifiable homicide." The gallery also contains a document by an investigator for the North End Family Center arguing that significant discrepancies existed between the accounts of the Black youth witnesses and the official version of the DPD and Wayne County Prosecutor's Office (as well as irregularities in the autopsy report), but that it would be difficult to bring a criminal case against Worobec because the prosecutor would always accept the word of police officers over civilians and because "the fact that some of the witnesses did not at all times tell the truth, no matter what the reason, could be used quite effectively against us in a court room." This was a reference to the teenage eyewitnesses who denied that they were present on the scene and otherwise did not tell police the full story, perhaps because they did not want to say that Buck and Mitchell had been involved in criminal activity, but presumably even moreso out of fear of retaliation because they saw police officers shooting their friends "in cold blood," as the leaders of the North End Family Center stated when summarizing their accounts. In fact, the North End Family Center memo reported "a whole rash of incidents" of police harassment and surveillance of Black youth in the neighborhood following the fatal shootings of Sept. 17, raising additional doubts about the impartiality of the DPD's investigation.

Investigative report of Wayne County Prosecutor's Office, Sept. 28, 1971 (5 pgs., juvenile witnesses redacted)

Coda: "Excessive Force," Selective Racial Criminalization, and Elusive Justice

Patrolman Richard Worobec expressed no remorse for taking the lives of two teenage boys outside the North End Family Center in an encounter that the undercover decoy officer himself initiated and escalated on the evening of September 17, 1971. In this way, the white police officer was operating within the racial logics of STRESS and advancing its explicit mission of the "proactive policing" of Black Detroit through the deterrent of deadly force. "If you say 'Halt! Police!' and the suspect keeps running," Worobec told the Detroit News, "then he's making an occupational hazard for himself. I have an occupational hazard every time I go out on the street. I think these guys ought to have an occupational hazard, too."