New Detroit Committee

Rebuilding the City

The political and business leaders of Detroit began the process of rebuilding the city, and repairing its reputation, even before the Uprising had fully come to an end. The main vehicle was the New Detroit Committee (NDC), planned as a partnership between public officials and the private sector, in particular the business community. The New Detroit Committee was a biracial organization of 39 civic leaders, led by department store owner Joseph Hudson, Jr., that included the head of the NAACP and several other traditional civil rights leaders, along with a few black militants. Nine of its members were African American.

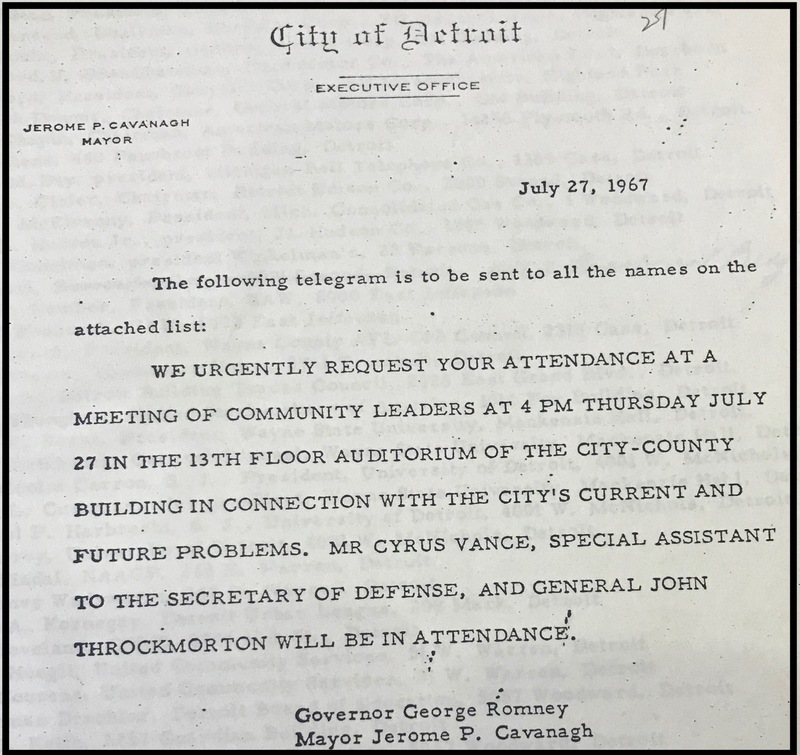

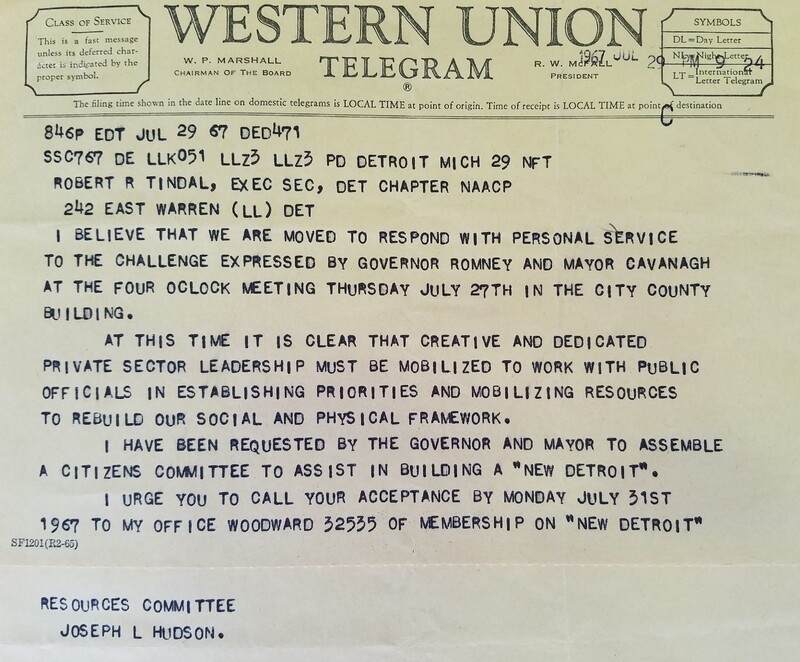

On July 27, Governor Romney and Mayor Cavanagh issued an urgent call to dozens of civic leaders to attend the meeting that resulted in the formation of the New Detroit Committee. The main focus would be on rebuilding the city and providing jobs to unemployed African Americans, which Cavanagh and other liberals considered to be the root cause of the racial unrest. White business leaders, including the heads of Ford and General Motors, expressed shock at the extent of the anger in Black Detroit and made a commitment to affirmative action in employment to try to address the crisis of joblessness for African American youth. The NDC also endorsed "open occupancy" for housing integration, urged construction of more low-income housing to relieve overcrowding, and pledged to help improve the city's school system.

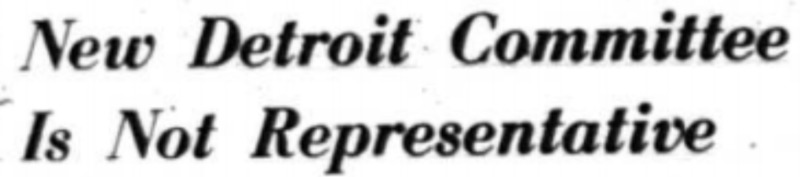

Joseph Hudson, the white businessman and NDC leader, proclaimed that the group represented "all the interests of the total community." Others disagreed, including the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's African American weekly, which said that most NDC members were "people who don’t care or are unaware about what happens to the inner city" (below right). Congressman John Conyers, who lived near the 12th Street epicenter, pointed out that the "voiceless people in the community, . . . anyone poor or black," did not have any representation at all.

"Law and Justice" + War on Crime

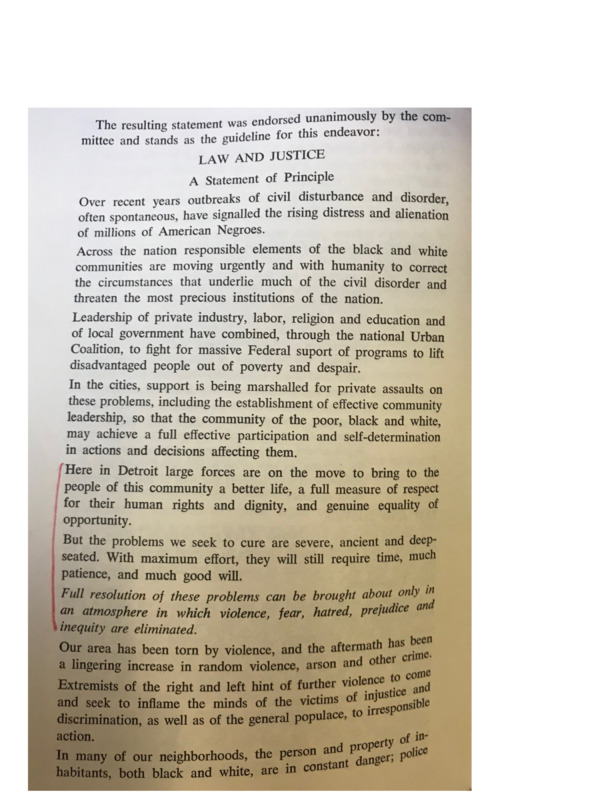

In a statement of principles titled "Law and Justice" (gallery below), the NDC declared that the civil disorders in Detroit and other cities had "signalled the rising distress and alienation of millions of American Negroes." The NDC believed that "responsible elements of the black and white communities" could solve the urban crisis. The organization also acknowledged that "society as a whole shares some responsibility for the events of last July." Its platform charted a liberal reform path, calling for spending to address root causes, rejecting black nationalism, and insisting on the necessity of maintaining "law and order":

- support for "massive" federal antipoverty programs

- private business contributions to address poverty and unemployment

- elimination of "violence, fear, hatred, prejudice, and inequity"

- rejection of "extremists of the right and left"

- police protection of all communities that suffered from "violence and crime"

- "our society can survive only with respect for law"

- "society must and will act to protect itself against all forms of lawlessness"

- "by the same token, the law cannot stand if it is not justly conceived and justly administered"

The New Detroit Committee's position on the issue of police reform in the "Law and Justice" manifesto was moderate and cautious, and its specific proposals were identical to what the Cavanagh administration had been promising since 1962 in its pledge for crime control through equal protection of the law. The "Law and Justice" program involved:

- Equal protection of the human and civil rights of all citizens in the process of arrest, search, or seizure

- Equality of treatment by the legal profession and the courts

- Non-discrimination in hiring and advancement in all police forces

- Equally effective police protection of the persons and property of all citizens without regard to race or station in life

The New Detroit Committee endorsed a "major assault on violence, crime, and juvenile delinquency" as part of its program of equal treatment under law. Its belief that such a program could be color-blind reflected the optimism and the naivete of liberalism in the 1960s, and it came as the Cavanagh administration was finalizing a stop-and-frisk law that was enacted in 1968 and that the DPD primarily, and predictably, enforced through racial profiling and brutal tactics in poor black neighborhoods.

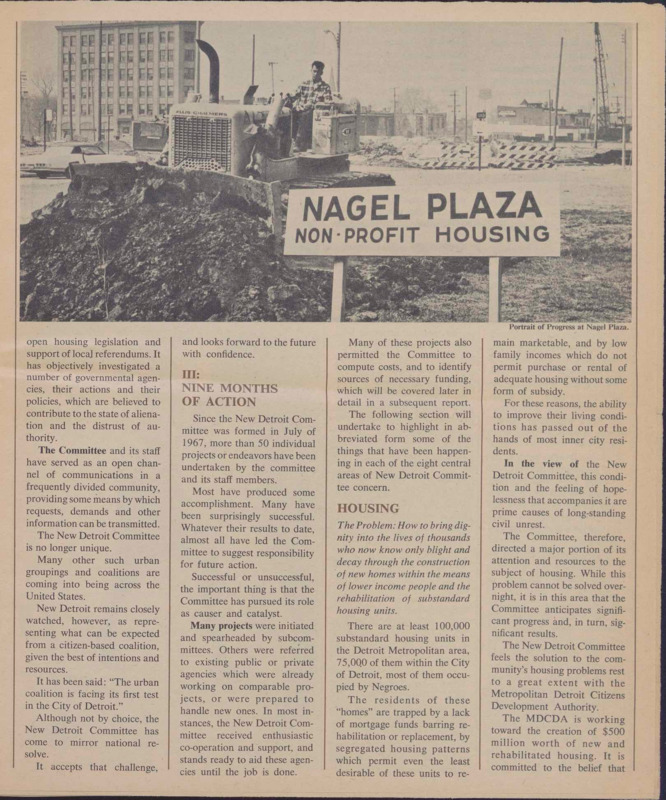

The New Detroit Committee's "Law and Justice" vision, notably, did not say anything specific at all about either the prevalence of police brutality and misconduct or the inadequate investigative process for civilian complaints. In a follow-up publication (gallery, far right), the NDC did suggest that "attention should be given" to the longstanding civil rights demand for an independent civilian review board to investigate police brutality and misconduct. This was a weak position that failed to reckon with the pervasive problem of police violence in Detroit's poor black neighborhoods, a problem that even the moderate Detroit Urban League identified as the primary grievance of African American residents of the city.

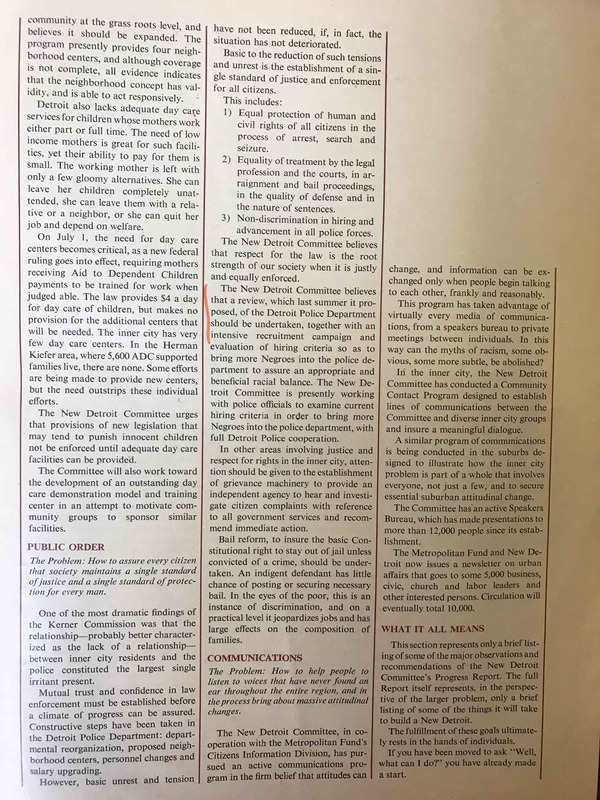

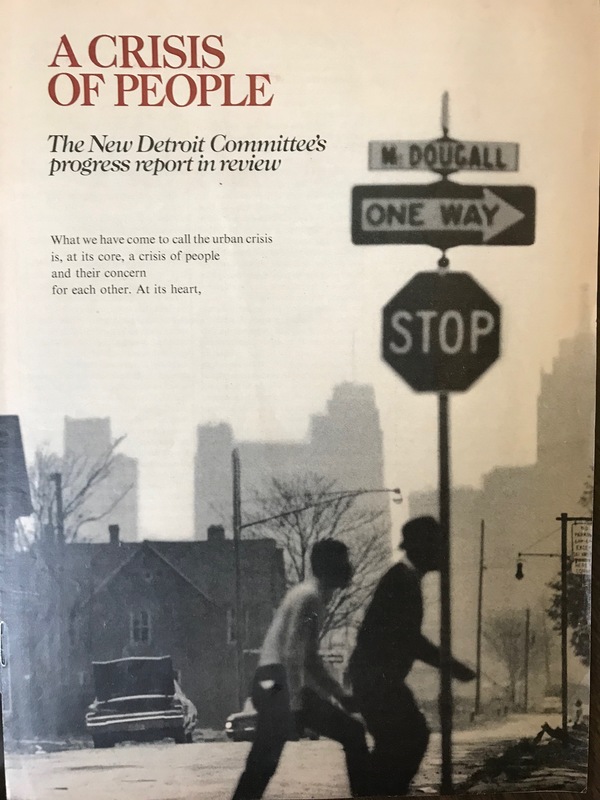

"A Crisis of People"

In May 1968, nine months after the Uprising, the New Detroit Committee released a progress report titled "A Crisis of People." The report sought to address the urban crisis in the wake of the Kerner Commission's findings that "white racism" was the fundamental cause of racial disturbances and that police brutality was the immediate trigger.

The New Detroit Committee argued that a solution was possible if the city and the nation were prepared to "pay the price" and spend "vast sums of money" to address the root causes. The riots of July 1967 were a wake-up call, but so far the city of Detroit and the rest of the nation had failed to respond adequately.

The "Crisis of People" report, echoing the Kerner Commission, also insisted that white Americans must confront their racial prejudices and that white society had to remove the informal as well as formal barriers to racial equality. But what did this mean, exactly?

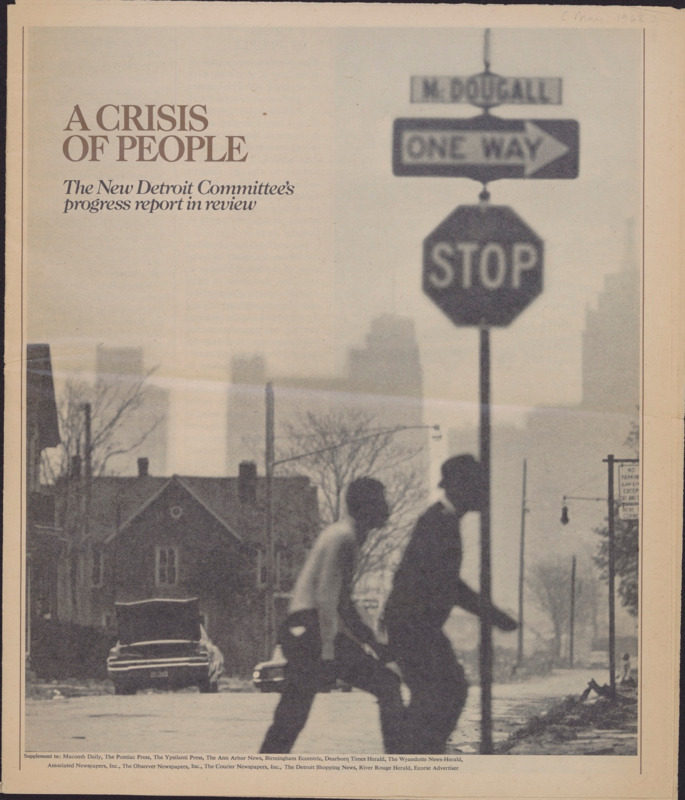

The NDC called, first and foremost, for "federal involvement in terms of great sums of money and leadership . . . in order to address the continuing growth of inner city hopelessness and despair." The main challenges involved housing and jobs. First, the city of Detroit and state and federal governments needed to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on improved and affordable housing, along with enforcement of open-occupancy laws to promote racial integration. Second, the major corporations in particular had to provide jobs for the "hard-core unemployed." In addition to these proposals, the NDC called for major investments in a range of social welfare programs in the inner city, from public schools to youth recreational facilities.

The section on "Public Order" (p. 11, in the third packet below) raised one of the most difficult questions of all:

The NDC reiterated its commitment to equal protection by law enforcement, equal treatment in the criminal justice system, and nondiscrimination in police hiring and promotion. But this was the same thing that liberals had been saying for years: a philosophy of equality in the abstract, not a concrete plan of action, and with little awareness that the promise of a crackdown on crime and disorder would undermine all of these ideals.

The NDC did endorse one specific policy that would have had a major imact on poor black Detroiters entangled in the criminal justice system: bail reform to end the practice of holding impoverished people in the inhumane conditions of the local jail indefinitely while they were presumed innocent and awaiting trial.

The NDC also reiterated its oblique suggestion that the city should consider ("attention should be given") an independent agency to investigate police misconduct and brutality, rather than letting the DPD continue to police itself. Compared to the forceful demands for federal antipoverty funding, this was, as before, a very weak stance to take on an issue that civil rights organizations had been demanding for a full decade. It seems clear, reading between the lines, that the NDC was internally divided and that the white business leadership in particular did not support civilian review of the DPD.

The NDC concluded with a statement of obvious truth and also of considerable futility, considering how badly the relationship between the DPD and the African American community had already deteriorated since July 1967 and how much worse it would get over the next half-decade:

Read the full version of the New Detroit Committee's "A Crisis of People" May 1968 report below.

Sources:

Joseph L. Hudson Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

NAACP Detroit Branch Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Michigan Chronicle, August 12, 1967

Hubert G. Locke, The Detroit Riot of 1967 (1969, reissued 2017)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2007)