Patterns of Police Brutality/Misconduct

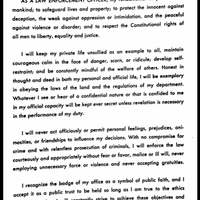

The Detroit Police Department required all new police officers to memorize the "Law Enforcement Code of Ethics" (right) and placed it at the front of each version of the Detroit Police Manual. Among its provisions, police officers took an oath to "enforce the law courteously and appropriately, . . . never employing unnecessary force or violence," and to "respect the Constitutional rights of all men to liberty, equality and justice."

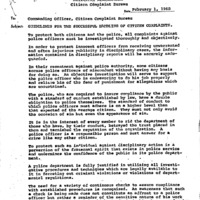

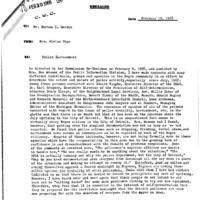

Most African Americans in Detroit did not bother to file formal complaints of police brutality and misconduct, because almost nothing ever happened and police officers often retaliated against civilians who did. The Civilian Complaint Bureau, the DPD's internal investigation unit, was deliberately understaffed, relatively impotent, and inclined to accept police testimony at face value and to whitewash inquiries unless the conduct of an individual officer was completely egregious and impossible to dispute (and sometimes, even then). The CCB's findings were not public, and its stated justification for this was to "protect innocent officers" who were often falsely accused by citizens in "their resentment against police authority" (right). The CCB's rare recommendations for discipline also did not matter unless the DPD commissioner chose to impose it or decided to refer the case to a police trial board.

The Detroit Police Department did not terminate a single officer for an on-duty allegation of police brutality made by a civilian during the entire decade of the 1960s. At most, a few officers over the years received verbal reprimands for actions that clearly rose to the level of felony assault. So it is not surprising, as the Michigan Civil Rights Commission reported in 1968, that few civilians even filed complaints because of "lack of confidence in and disenchantment with" the process. Civil rights groups persistently demanded a civilian review board, and the DPD remained, as Commissioner John Nichols stated in 1970, "unequivocally opposed."

Documenting and mapping patterns of police brutality and misconduct will inevitably capture only a very small percentage of the actual encounters between police and civilians that fall into these categories. The DPD's internal investigative records were and remain confidential, and so the archives are full of silences. The incidents that are discoverable generally are the ones that protesters escalated to the attention of the mayor's office or the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, or that happened to make the newspapers because of publicity by civil rights organizations (unfortunately, the NAACP's papers are missing for this time period). The civilians who escalated incidents by pursuing formal complaints generally were either middle-class black families or political activists, or both, and very few came from residents of poor black neighborhoods who lived with police harassment on an everyday basis--"so commonplace as to be expected by much of the Negro community," as the Michigan Civil Rights Commission observed in 1968.

This page maps patterns and highlights everyday incidents and resulting complaints of Detroit Police Department brutality and misconduct between 1968 and 1970 based on a special investigation conducted by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission in the aftermath of the 1967 Uprising and on the additional cases that our research team discovered through laborious research in multiple archives and newspaper databases. Elsewhere in this section, please find a dedicated map of 24 incidents of brutality and misconduct against the Black Panther Party in 1969-1970, and detailed examination of high-profile mass brutality incidents against political activists in public schools and during downtown demonstrations, against youth at Veterans Memorial and Balduck Park, and against black radicals at the New Bethel Church.

Special Investigation: Michigan Civil Rights Commission

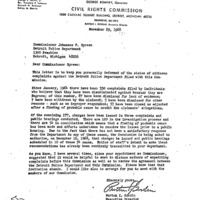

During the late 1960s, African Americans in Detroit increasingly filed complaints of police brutality with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC), in recognition that the DPD's internal investigative process was designed to fail them. The MCRC aggressively investigated civil rights violations but also lacked disciplinary power and could only make recommendations to the Detroit Police Department, which proceeded to do nothing at all with the findings.

In February 1968, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission conducted a special investigation of police brutality and misconduct toward African Americans in Detroit since the July 1967 Uprising. The report found that stop-and-frisk policing was ubiquitous, that white officers frequently used racist language, and brutality was surging.

The MCRC report documented 21 specific incidents of police brutality and misconduct, contained in the document at right and mapped below. Many of the incidents happened in the racially transitional area of Northwest Detroit, an indication that white police officers were regulating the color line and harassing black youth, pedestrians, and motorists in recently integrated areas and on the borders of white neighborhoods (a longstanding practice), rather than fighting crime. The incident report includes many stops of African Americans for no valid reason, often accompanied by physical brutality and racial epithets. African American women and teenage girls reported being called "black bitch" and "whore" by white officers, along with physical assaults. African American men and teenage boys reported being searched, and in some cases illegally detained, on groundless suspicion of being rapists and robbers. A number of the incidents were retaliatory, targeting African Americans who had previously filed complaints about police brutality. In several of the encounters, the white police officers told the African American civilians variations on how they were looking forward to the next riot so that they could "kill all of you n------."

Map of brutality/misconduct incidents against African Americans between Sept. 1967-Feb. 1968 uncovered by Michigan Civil Rights Commission, in Detroit's racial geography (based on 1970 census)

Note: black = police brutality; red = police misconduct. All of these incidents involve African American victims. Zoom the map to view the cluster of incidents in a racially transitional area of Northwest Detroit (top left) and read more about this neighborhood here. Note that the African American families that moved into recently all-white areas of Northwest Detroit were primarily middle-class professionals and were much more likely to file complaints after police incidents. There are few incidents on this map from the poorest black areas of either the West Side or the East Side, but that is a function of who filed complaints rather than an indication of a lack of police harassment in those areas.

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission escalated its criticism of the DPD in 1968, after the CCB had refused for months to investigate any of the dozens of civilian complaints forwarded by the state agency based on incidents that happened during the 1967 Uprising, and then also refused to take any actions on the incidents in the investigation report recounted above. The gallery below contains several documents from the MCRC charging the DPD under three consecutive police commissioners with refusing to act on its findings of proven police brutality in hundreds of cases between 1967 and 1970.

The MCRC additionally denounced the "Blue Curtain," which it called "injurious and patently unfair to the public" and defined as the "unofficial, unwritten code within the department which prohibits an officer from making any official statement that would expose the misconduct of a fellow officer." In addition to these obstacles, the DPOA union filed a lawsuit contesting the MCRC's authority, which hamstrung its investigations for almost two years, as members of the police union flatly refused to testify in any inquiries. The litigation ultimately resulted in a 1970 consent decree that reaffirmed the state agency's authority to conduct investigations but strengthened due process rights for police officers and adjudicated that, because of the collective bargaining agreement, only the DPD trial board or commissioner could impose punishment. (In these rare cases, the DPOA routinely appealed to arbitrators or to the courts, often with success).

On March 20, 1970, at the height of this standoff, Burton Gordin, the executive director of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and a 50-year-old white man, was murdered in a Detroit parking garage. Many civil rights activists suspected that the DPD or DPOA union was behind the murder of one of their most vocal critics, and the head of the state NAACP called it a "political assassination." The DPD Homicide Bureau did not seem to try very hard to identify the killer in a case that it labeled a botched robbery attempt, even though nothing was stolen (read the DPD Homicide Bureau investigation report here). The murder of Burton Gordin has never been solved.

All Police Incidents (1968-1970)

This interactive map displays 78 allegations of police brutality and misconduct, almost all by African American civilians, against the Detroit Police Department between the years 1968 and 1970, identified through archival documents and newspaper reports. Many of these incidents involved multiple victims. The incidents are mapped on Detroit's racial geography at the time of the 1970 census, with dark blue indicating the most segregated all-black neighborhoods and dark green the most segregated white areas. Hover over the dots to read the incident description, and zoom in to see concentrations of cases downtown and elsewhere. Please note that police homicides and non-fatal shootings of civilians are mapped on a separate page.

- Black circles (41 incidents) = Police Brutality

- Red circles (37 incidents) = Police Misconduct

Case Studies of Police Brutality and Violence

This section profiles six incidents of police brutality included in the above map, involving twelve mostly young residents of Detroit. Several of these cases represent the growing pattern of police brutality escalating from stop-and-frisk procedures targeting black motorists and pedestrians--which happened hundreds of thousands of times each year during this era. Police brutality during stop-and-frisk encounters was particularly common when the civilian asserted constitutional rights, objected to racist language, and otherwise did not display complete obeisance to the authority of the police. The violence against women in four of these encounters also reflects broader patterns: police retaliation against African American women who protested police brutality against their male relatives; police criminality, including rape and sexual assault, against sex workers; and police harassment and brutality against youth of all races perceived to be violating sexual norms.

Charles Moore, a young African American male, was driving on Jan. 22, 1968, when a Tactical Mobile Unit squad car pulled him over (the TMU stopped and investigated at least 50,000 motorists in 1968 in a massive racial profiling operation that rarely resulted in arrests). The TMU demanded to search Moore's car, allegedly because he resembled a bank robbery suspect, and ordered him out of the vehicle to be frisked. Moore asked to be taken to the precinct station to be searched instead. The officers called him a "no good n-----" and beat him on the street, placed him in the squad car and continued to beat him, and threatened to kill him. Moore was charged with resisting arrest, meaning there was no underlying crime. He received treatment at Receiving Hospital. When Charles Moore filed a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, he noted that he was a witness against the police in the Algiers Motel murder cases, which might have been connected to the encounter. Moore also described a second incident in Sept. 1967 when he was stopped and searched on the allegation that he resembled a robbery suspect. The officers repeatedly called him racial epithets during this encounter as well.

Wally Triplett, a 42-year-old African American man, was a public school teacher in Detroit and a famous former professional football player (he was the first black player ever drafted in the NFL). On July 16, 1968, Triplett was driving on the East Side of Detroit near the entrance to Belle Isle when his car stalled. Four police officers arrived as he was trying to figure out how to call a tow truck. One of the officers demanded that Triplett move the car or receive a citation. The officer then ordered Triplett to get out of the car (presumably for a stop-and-frisk of his person). Triplett said that he would accept the citation but had a legal right to remain in his automobile. The officer then struck Triplett through the window with his fist, and the group of policemen dragged him out of the car and beat him with blackjacks on the sidewalk. The officers arrested him for "disturbing the peace." He ended up seeking treatment at Receiving Hospital. Because of Triplett's standing in the community, multiple prominent black officials called the mayor's office to protest. The police department claimed that Triplett had caused the encounter and that if he had any injuries at all, it was possibly becase his handcuffs were too tight.

Isaac Hale, a 20-year-old African American, was walking in the evening with three friends on Holcomb St. on Detroit's East Side when police officers pulled over and stopped and frisked them for no reason except racial profiling. They handcuffed Isaac Hale and beat him in the street. His sisters, Alma and Laura Hampton, witnessed these events that took place near their house and began to follow in their car as the police drove away with Isaac inside. The police car stopped, and the officers called Alma Hampton vulgar racial names that she informed Mayor Cavanagh, at right, that she could not repeat in a letter. The officers then beat her brother some more and also kicked, choked, and spit on him. They arrested Alma and Laura Hampton and said, "a n----- don't have any rights."

M. H., a 21-year-old African American woman and sex worker (name anonymized), was raped and stabbed in the neck and back by two Vice Bureau police officers, Robert Jones and Carl Woods, on June 7, 1969. The officers picked her up with the expectation that she would have sexual relations with them in exchange for not being taken to jail for soliciting, but she refused and so they assaulted her. After she filed a criminal complaint, the officers were suspended and then charged after an internal investigation (a very rare occurrence), and the victim also filed a civil lawsuit. The Detroit Police Officers Association union then negotiated a settlement by paying her $5,000 to settle the civil lawsuit, on the condition that she also drop the criminal charges. When she withdrew as a cooperating witness in the criminal proceedings, the Wayne County prosecutor asked the judge to dismiss the case. Prosecutor William Cahalan denied that the DPOA's $5,000 payment constituted bribery, to entice a victim to withdraw the criminal complaint, although that is exactly what the timing and nature of the union's intervention demonstrate. The Detroit Free Press reported that the civil lawsuit settlement between the DPOA and the victim was an explicit quid pro quo and quoted from the official civil litigation transcript that confirmed this was the case. The officers agreed to resign from the DPD as part of this negotiation. The victim stated to the newspaper that the DPOA attorney had told her that the union wanted to prove that it would "stick up for the colored officers" (the officers who assaulted her were African American) after also defending the white officers in the murder charges from the Algiers Motel Incident. The DPOA threatened to file a libel lawsuit against the Free Press for reporting the clear evidence of its bribery of the victim.

Diana Newland, a 23-year-old white woman, and her brother, 17-year-old Thomas Burger, were driving at night on Sept. 13, 1970, in Northwest Detroit, when their car stalled, and she eased it into a parking lot. Tactical Mobile Unit officers suddenly appeared and pulled both of them out of the vehicle and began beating Thomas. Diana was scared and began to run away. A TMU officer tackled her and handcuffed her and then ripped open her shorts and molested her. (Note: it seems likely that the TMU officers wrongly believed that they had caught a young couple in a sexual situation in the parking lot, in terms of why they escalated violence against two white people). The TMU officers arrested Newland and Burger for resisting arrest and claimed that Diana Newland had been driving recklessly at 70 mph when pulled over. Newland told the Detroit News, "that's a lie," and offered to take a lie detector test. The police transported Newland to the hospital for her extensive injuries and left her handcuffed to a bed there for 14 hours. She tried to file a charge with the Citizen Complaint Bureau but it went nowhere.

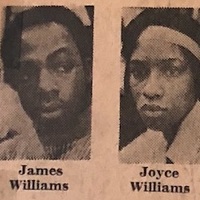

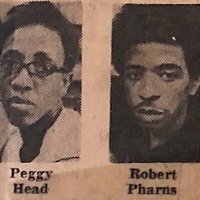

James Williams, Joyce Williams, Peggy Head, three African Americans between 20 and 21 years old, were driving on the East Side of Detroit when Patrolmen Terry Lambrecht and Dennis Elles stopped their car, allegedly for running a red light. The officers asked for the registration and James Williams, the driver, said he needed to go a short distance home to get it. The officers demanded that James Williams follow them to the station, but he did not want to, so Lambrecht told him he was under arrest and said "Come on, n-----. What are you up to, n-----?" Williams said he refused to comply because of the officer's racist language, and he also shoved Patrolman Lambrecht. Then Lambrecht began beating James Williams, and about 10 police cars quickly arrived for backup. These officers began manhandling the two females. Robert Pharns, a 20-year-old African American, came out of his house to help the females, and a policeman kicked him. TMU officers then began beating Joyce Williams, James's sister. At least 13 police officers participated in the beating of the four youth. All but Lambrecht and Elles were either in plainclothes or had removed their badges, making their identities hidden. Fifteen residents of the neighborhood where the encounter happened witnessed these events and told essentially the same story to a reporter. The police arrested the youth for interfering with police officers, but the prosecutor dropped the charges after the media coverage, except for the red light violation. Two of the youth were college students, which is likely why the incident made the mainstream newspapers.

Systemic, Unpunished Police Brutality

The incidents documented on this page are just the tip of the iceberg. Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon, who joined the DPD as a patrolman in 1965, later worked in the internal affairs division, and eventually became chief of police in the 1990s, addressed the issue of police misconduct and brutality during this era in a 2019 interview with our project.

Note: Lily Johnston, a researcher in the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab, did significant work compiling the incidents for this page after the completion of the "Detroit Under Fire" class project.

Sources

Citations for incidents mapped are in the pop-up boxes.

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Community Relations Bureau, RG 83-55, Michigan State Archive

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

William Serrin, "How Well Does the City Police Its Police?" Detroit Free Press, July 10, 1968

Arthur Horwitz, "For Detroit, Battle for Civil Rights Comes with a Price: Why Burton Gordin's Life Should Not Be Forgotten," Michigan Chronicle, April 24-30, 2013

Detroit News, Jan. 13, 1970

Detroit Free Press, April 23, 1970, May 1, 1970

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1967), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library

Isaiah (Ike) McKinnon Interview, Part 1, December 3, 2019, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_rxtil0md/145739741