1. Policing after the Uprising

In the aftermath of the 1967 Uprising, the Detroit Police Department resisted almost all demands and proposals to reform its procedures and repair its relationship with the African American community. The Citizen Complaint Bureau stalled or stonewalled the promised investigations of civilian complaints of police brutality and misconduct during the racial unrest of July 1967 (see right). The police union, the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA), came under the control of a right-wing leadership during this period and vociferously defended the discretionary right of officers to use force, including through frequent litigation. The emergence of white law enforcement officers as an independent political power in the city made it even harder to investigate and discipline police for brutality and misconduct. Instead of addressing the police brutality that the Kerner Commission and Detroit Urban League, among others, had labeled the primary grievance of African Americans, the DPD denied that brutality was even an issue at all. The liberal white mayor, Jerome Cavanagh, defended the DPD and also denied that brutality was a systemic issue. In response, the traditional civil rights groups, and especially the newer radical and black power organizations, increased their calls for civilian review of the DPD and a broad spectrum of other reforms, including use of force restrictions and a majority-black police force.

Instead of meaningful reform, the Cavanagh administration and the DPD continued to escalate the militarization of law enforcement in black neighborhoods and implemented a stop-and-frisk law in 1968 that gave legal sanction to the department's policies of systematic racial profiling and hundreds of thousands of street searches of African American pedestrians and motorists each year. DPD officers also repeatedly violated the constitutional rights of civil rights and black power activists through sweeping, illegal crackdowns and violent assaults (and spying on their organizations). The next three sub-sections examine these specific episodes; the rest of this page details the futile efforts of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, and other civil rights organizations to reform DPD policies between 1968-1970.

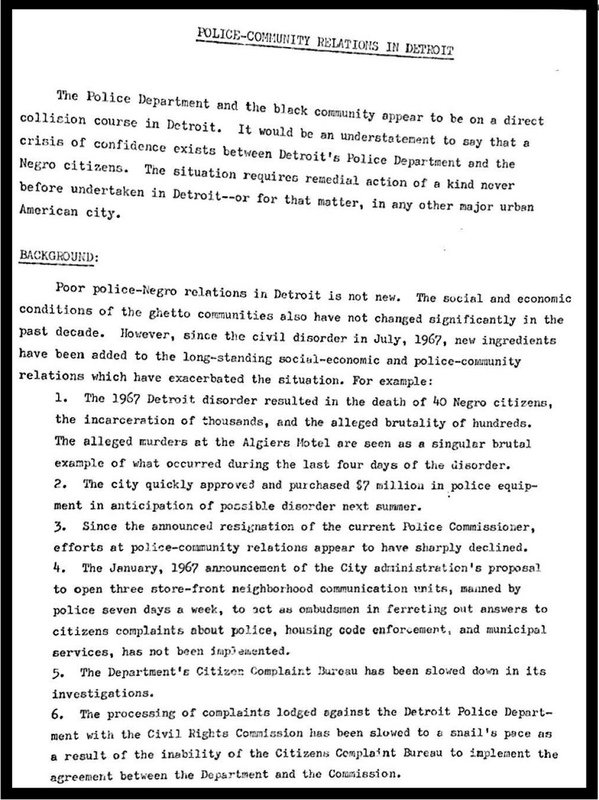

Michigan Civil Rights Commission Calls for "Drastic Overhaul"

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC), an agency of the state government, emerged as one of the DPD's strongest critics in the late 1960s. Beginning in 1964, the MCRC had begun to initiate brutality investigations against police officers for deprivation of civil rights, although the agency lacked disciplinary power and the DPD almost always refused to implement its recommendations (as in the Barbara Jackson case). Leading up to 1967, the MCRC also had repeatedly warned that that the police department was creating the conditions for a riot in Detroit, only to be ignored by the Cavanagh administration and the DPD hieraerchy.

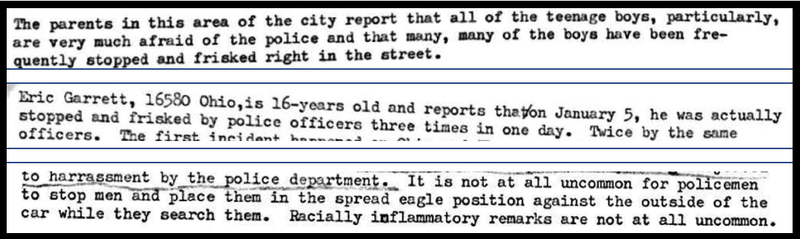

After the July 1967 Uprising, the MCRC launched a field investigation in the city of Detroit to document the actions of the DPD and the responses of grassroots organizations in the African American community. The MCRC was very worried that the summer of 1968 would bring another "civil disturbance," especially without a change of direction by the police department. The MCRC's investigation stated that there was "no doubt" that police brutality and racist harassment of black citizens had increased since the 1967 Uprising and that stop-and-frisk tactics in particular were leading to abuses and enraging black residents of Detroit. (See the Patterns of Police Brutality page for the full investigation report and a map of the incidents uncovered). The MCRC report then explained that the relatively low number of formal complaints only meant that African Americans felt that there was no reason to file a grievance when nothing ever happened. The investigation also confirmed the views of many black Detroiters that police officers retaliated against civilians who filed formal complaints.

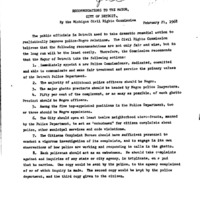

Based on its investigation, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued an urgent warning to Mayor Jerome Cavanagh to "take dramatic remedial action to realistically improve police-Negro relations" (right). The MCRC's recommendations included:

- Immediate implementation of an affirmative action program to ensure that African Americans made up a majority of new police officers hired, a majority of top commanders, and at least half of officers and every inspector in charge of "ghetto precincts"

- Immediate reform of the process for investigating police brutality and a meaningful commitment to punish officers who violated the rights of citizens

- Local civilian advisory committees for every precinct

- An end to stop-and-frisk practices and verbal/physical abuses, "which tend to incite citizens"

None of this happened, with the partial exception of hiring more African American officers, which Mayor Cavanagh and DPD commanders supported as necessary for police legitimacy in a city with a near-majority of black residents. Between 1968 and 1970, the DPD simply refused to conduct meaningful investigations or punish officers for brutality and misconduct in any but the most egregious situations, despite constant pressure and escalating criticism from the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and other organizations. And instead of curbing stop-and-frisk abuses, the city of Detroit codified police authority to conduct street searches a few months later (see below).

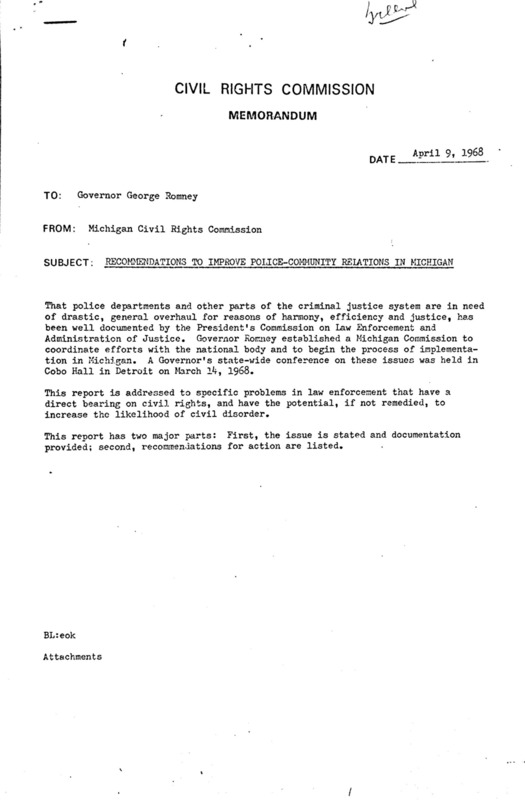

In April 1968, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission released a second report on improving police-community relations throughout the state of Michigan. The report documented the patterns of police brutality against African American residents of Detroit and other cities and stated conclusively that the police could not and would not "police themselves," as law enforcement at all levels protected its own through the "Blue Curtain" of silence. The MCRC further charged that Michigan police departments were not screening out racially biased officers, not providing adequate training for new recruits, and not addressing the racial discrimination in their hiring and promotion processes (in Detroit, only 6 percent of officers were African American). The MCRC report urged the state government to implement affirmative action to hire far more African American (and Latin American) officers, clarify and restrict the use of force by law enforcement, and mandate that every local department create a workable and transparent process for investigating and punishing officer misconduct. Read this MCRC report in the gallery below.

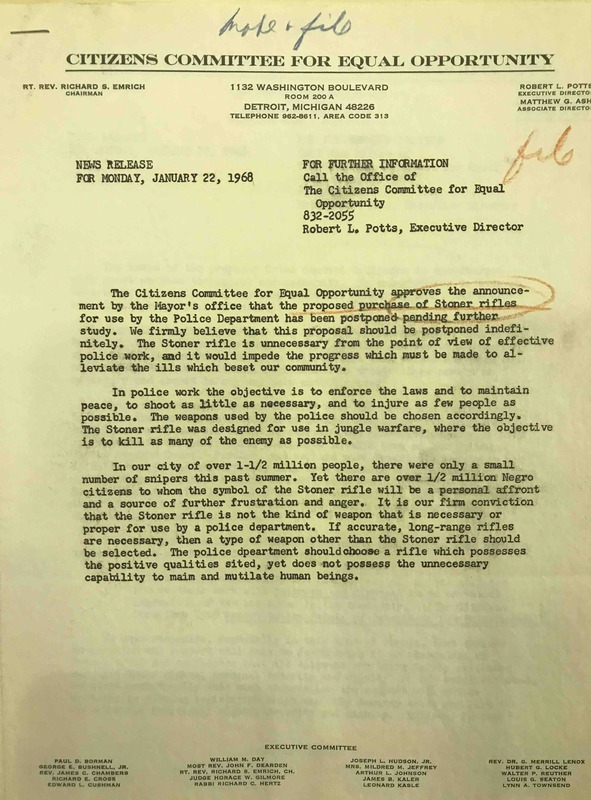

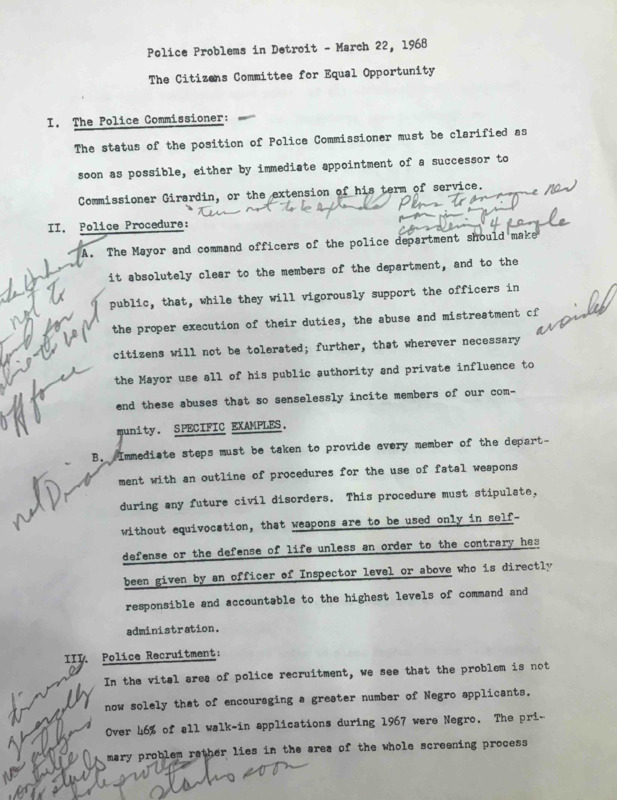

Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity: "Police Problems in Detroit"

The Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity (CCEO), a group dominated by white liberals, also called on Mayor Cavanagh to immediately reform the police department in the spring of 1968. In January, the CCEO denounced the proposed stop-and-frisk ordinance as "unjustifiable and harmful" to effective law enforcement, because the policy "has historically been used primarily against Negro citizens" and had resulted in their anger and mistrust toward law enforcement. "The last thing that Detroit needs at this time," the CCEO observed, "is something that will add fuel to the fire of a justified sense of abuse, discrimination, and frustration" (below left). The CCEO also spoke out against the increased militarization of the police department, including the purchase of long guns and assault-style rifles that appeared designed to intimidate the residents of black neighborhoods (below, second from left).

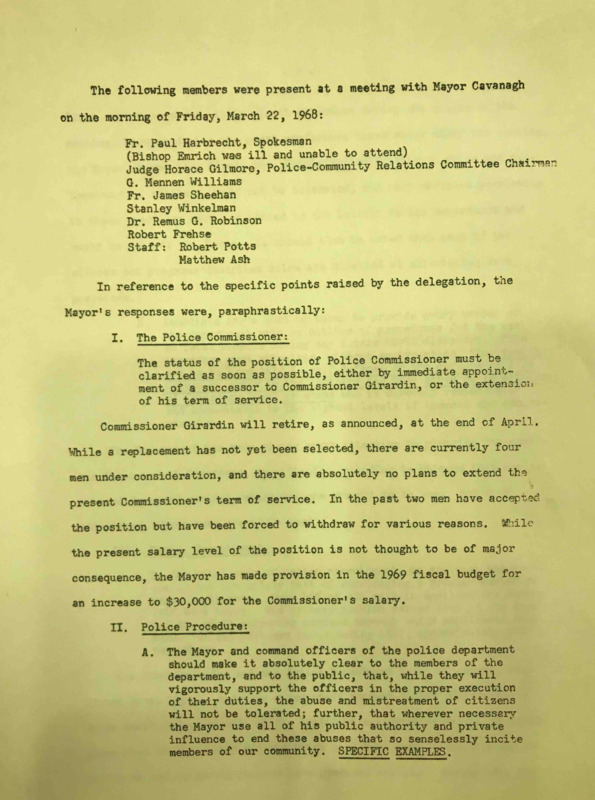

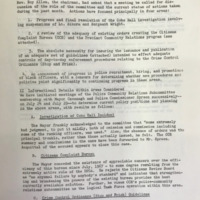

In March 1968, the Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity met with Mayor Cavanagh and presented its list of recommendations for addressing "Police Problems in Detroit" (below right). The CCEO demanded an end to DPD brutality against citizens and also urged the mayor, in the event of another civil disturbance, to clarify that officers could only use deadly force in the defense of life, not property (a reference to Cavanagh's lack of leadership and granting the DPD discretion to sanction the shooting of looters during the 1967 Uprising). The other CCEO recommendations closely tracked the proposals of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, including affirmative action in police hiring and promotion and an end to the "whitewashed" investigations of police brutality by the Citizen Complaint Bureau.

Immediately after the CCEO meeting, Mayor Cavanagh held a press conference and announced that "abuse and mistreatment of citizens would not be tolerated" and that officers who did so would be fired. Despite the mayor's liberal rhetoric, not a single police officer received this punishment during his eight years in office, and the Citizen Complaint Bureau remained a completely ineffective organization, as detailed below.

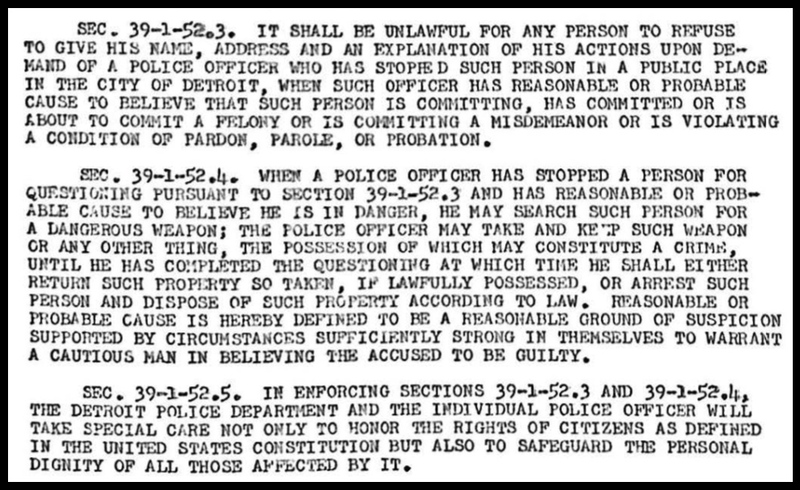

Detroit's Stop-and-Frisk Law (1968)

Instead of reforming DPD abuses, the Cavanagh administration successfully fought for a stop-and-frisk law to empower police discretion and lower the legal standard for searching civilians from probable cause to "reasonable suspicion." Mayor Cavanagh had initially proposed a stop-and-frisk ordinance in 1965 (as detailed in the "Liberal 'Get-Tough' Policies" section of this exhibit). But the administration backed down after the fierce resistance of the NAACP, ACLU, and a broad spectrum of African American community leaders and elected officials.

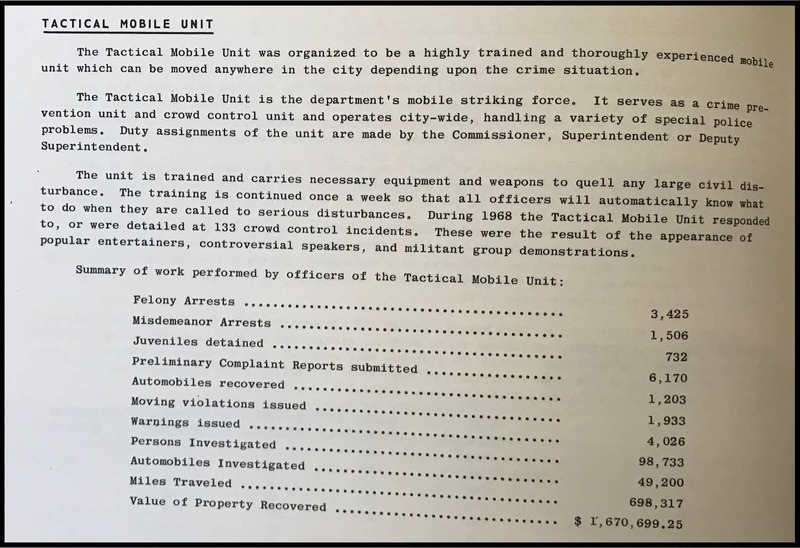

Even without a formal law, the DPD engaged in racial profiling and discretionary stop-and-frisk policing on a massive scale, primarily targeting African Americans. The Tactical Mobile Unit alone "investigated" between 150,000 and 200,000 pedestrians and motorists every year during the mid-to-late 1960s, with the overwhelming majority of stops finding nothing illegal. In the 1968 data, for example, the Tactical Mobile Unit "investigated" 98,733 persons and 49,200 automobiles while arresting only 5,663 people (although the data is inconclusive, a majority or near-majority of these arrests did not result in formal charges). The DPD did not publish data on the total number of investigative stops and searches by its officers, beyond the specialized TMU "strike force," but it would certainly be several multiples higher. The proposed stop-and-frisk ordinance sought to codify this discretionary authority by making the police officers' own "reasonable cause of suspicion" the standard for allowing searches of anyone in a public place.

The July 1967 Uprising changed the political equation in Detroit and led the Cavanagh administration to push again for a stop-and-frisk ordinance as part of its targeted crackdown on "criminals" and "radicals" in Detroit's black neighborhoods. The Supreme Court's ruling in Terry v. Ohio (June 1968) also made clear that the discretionary standard of "reasonable suspicion" was constitutional. During the debate, thousands of white residents of Detroit wrote letters to the mayor demanding a stop-and-frisk law to empower the police department and protect the "law-abiding" citizens (see this page for a gallery of letters). Every civil rights organization and prominent African American leader opposed the stop-and-frisk ordinance.

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission, which had released a major report on the DPD's stop-and-frisk abuses in February 1968 (above), testified against the proposed law before the Detroit Common Council. The MCRC warned that passage of the law would further inflame racial tensions and would "legitimatize practices designed less to apprehend criminals than to harass, intimidate and treat with indignity law abiding citizens." Strikingly, the MCRC accused the advocates of stop-and-frisk of supporting a policy of "containment and repression."

In July, Mayor Cavanagh signed the stop-and-frisk ordinance after it cleared the Common Council by a 5-2 vote. The mayor defended the action as essential for crime control and compatible with his longtime vision of "law, order and justice in this city." He also promised that the DPD would enforce the law "fairly and firmly" and would "protect the rights of the individuals from abuse." And in a remarkable statement, Cavanagh claimed that "'police brutality is a thing of the past" and that "the climate has completely changed." In addition to ignoring evidence of police brutality in the July 1967 Uprising and the everyday occurrences documented by civil rights groups, the mayor made this statement less than two months after a large group of DPD officers brutally attacked nonviolent civil rights marchers in the May 1968 Cobo Hall incident.

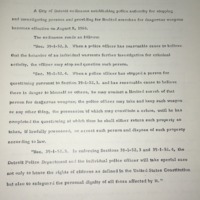

The DPD subsequently released guidelines pledging that the ordinance would be implemented without racial discrimination, based only on the legitimate, "reasonable" suspicion of the individual police officer. The Detroit Commission on Community Relations, basing its analysis on actual history and reality, acknowledged that the DPD had completely failed to prevent or discipline brutality and constitutional abuses by its officers thus far and that city officials had enacted the stop-and-frisk law as a "symbol in response to a fear-charged community" [meaning white residents] and therefore further alienated the African American citizens of Detroit. Read these documents in the gallery below.

Detroit Commission on Community Relations: Failure of Internal Reform

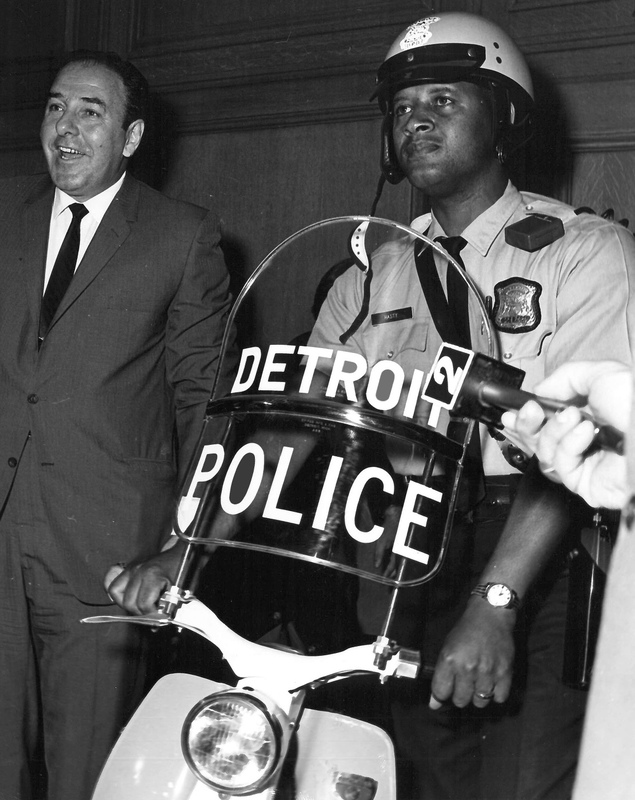

Mayor Cavanagh appointed a new DPD commissioner, Johannes Spreen, in the summer of 1968, after Ray Girardin retired. Spreen was a mild-mannered leader and an advocate of police professionalization, community-oriented patrols, and racial diversification of the force. His main energy went into a public relations campaign designed to change the terrible image of the Detroit Police Department with the African American community through marketing rather than new policies. Spreen's promotional event at right, with African American officers riding scooters as part of the Community Oriented Patrol, is typical of the style over substance approach of the new DPD commissioner, who served through the end of Cavanagh's second term in 1969. Spreen made no visible efforts to address the underlying problems of police brutality and misconduct that had deepened the distrust between the DPD and the city's African American residents, even after the Michigan Civil Rights Commission publicly accused the department of refusing to cooperate in brutality investigations throughout 1968 and 1969. Racial polarization worsened considerably during Spreen's year and a half as commissioner.

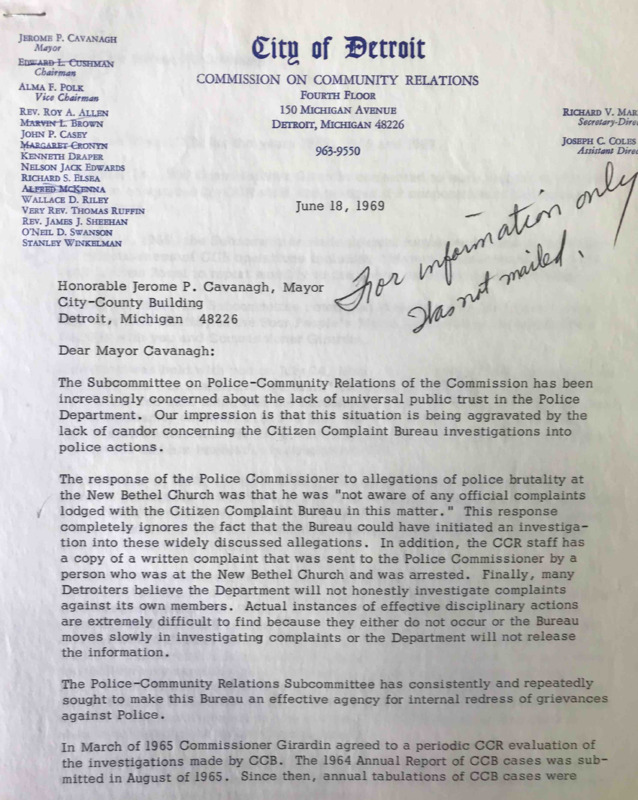

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR), the city government's main civil rights agency, warned Commissioner Spreen right after his appointment in summer 1968 that the Citizen Complaint Bureau was widely seen to be an "abysmal failure" and that the stop-and-frisk ordinance had outraged black residents (above gallery, right). Then, in January 1969, a major expose in the Detroit Free Press detailed the institutional failures of the CCB for all to see. In the story's bombshell, the head of the CCB stated publicly about abusive officers:

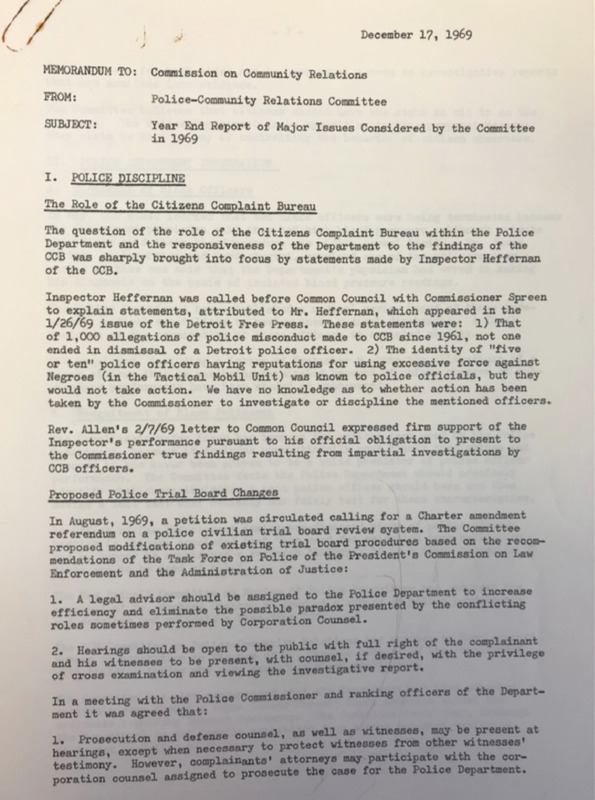

The Free Press reported that the Detroit Police Department had received around 1,000 formal complaints of police brutality and misconduct since the establishment of its internal investigation process in 1961, and no police officer had ever been fired. Suspensions were extremely rare. Only one case during the entire decade had resulted in a criminal prosecution. When the CCB did find a complaint to be valid--which required overwhelming evidence, because by default the process took the officer's word over a civilian's without elaborate corroboration--sole discretion for discipline rested with the police commissioner. In almost every case, the commissioner settled on a verbal "warning" in an informal conference with the officer. On a few occasions, the officer was transferred to another precinct or had to write a letter of apology to the civilian. The DPD had even given only a verbal reprimand to an offer who beat a civilian so badly that the police department agreed to cover the hospital costs (in other words, after acknowledgment that the officer committed a felony assault). And, in evidence of the "Blue Curtain," no police officer had ever referred a fellow officer to the CCB for misconduct, and officers almost never testified against other officers during its investigations.

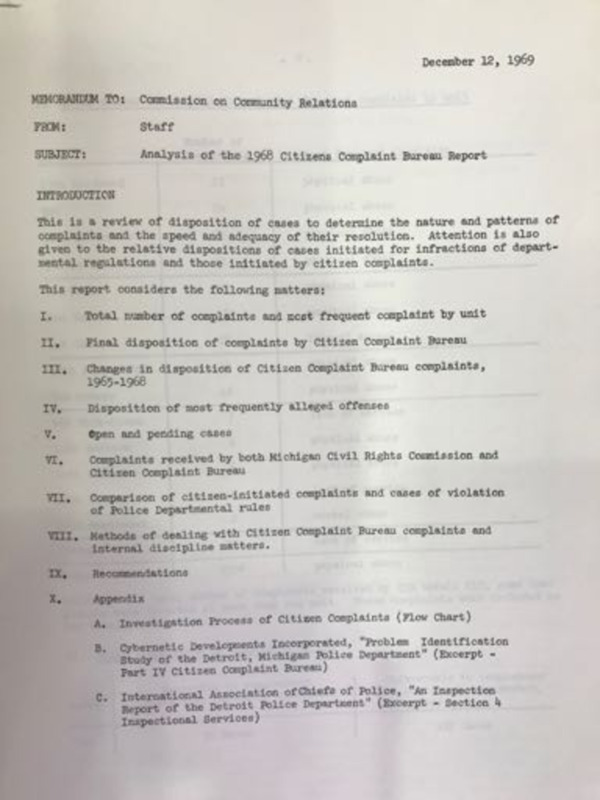

The DCCR fought a losing battle to reform the Citizens Complaint Bureau under Commissioner Spreen. Its analysis of the CCB's activities during 1968 found a huge backlog combined with the commissioner's failure to act on completed investigations. The Detroit Police Officers Association union also contributed to the breakdown by withholding officer testimony and otherwise stonewalling the investigative process however possible. The DPD refused to make its disciplinary decisions public, even in the aggregate. The DCCR concluded, with bureaucratic understatement, that "this agency and others must continue to raise the issue of whether the Police Department has the will to take action in behalf of citizens who are adversely affected by police misconduct" (gallery, below left).

In June 1969, the DCCR alerted Mayor Cavanagh, again in polite bureaucratic euphemisms, of the "lack of universal public trust in the Police Department," especially after the mass arrests of black radicals and regular churchgoers in the New Bethel Incident. The DCCR accussed Commissioner Spreen of stonewalling its requests for information and reforms of the completely ineffective process and noted that the mayor continued to insist, against all evidence, that the CCB was an efficient agency. The DCCR reminded the mayor that "the actions of the police are the public's business" and warned of growing anger at the DPD (gallery, second from left). At this time, in the summer of 1969, African American leaders and a new anti-police brutality organization called the Ad Hoc Action Group were launching a new, although ultimately unsuccessful, effort to establish a civilian review board.

The DCCR again strongly criticized the DPD's lack of transparency and failure to investigate or punish officer misconduct in its December 1969 year-end report. The DCCR also found that white police officers were intimidating African American civilians with a practice of driving through their neighborhoods with the barrels of their long rifles out the window, a deliberate show of force that was inflaming racial tensions. The DCCR observed:

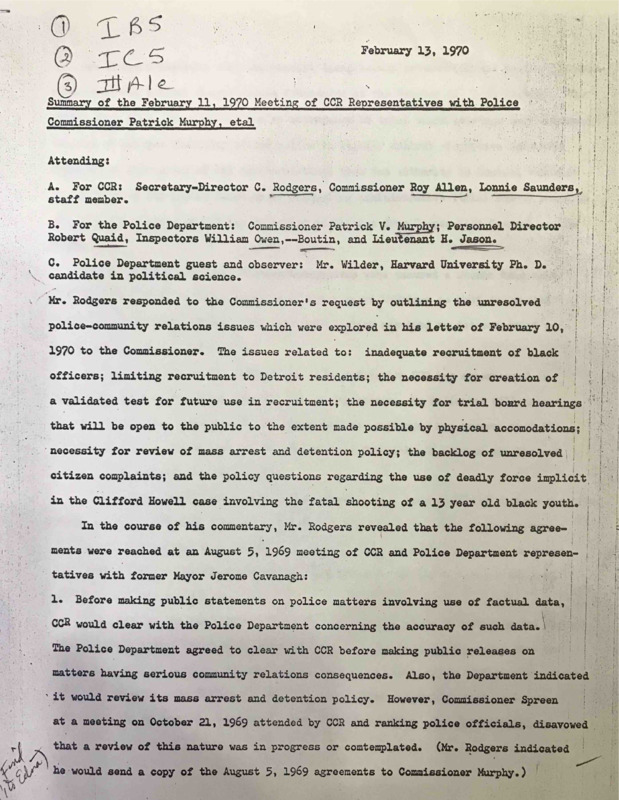

In February 1970, the DCCR summed up two years of futile interaction with the DPD in a memo to the new police commissioner, Patrick Murphy, who had been appointed by Roman Gribbs, the former Wayne County sheriff and conservative Democrat who succeeded Cavanagh as mayor of Detroit. As "unresolved issues," the DPD listed:

- "inadequate recruitment of black officers"

- lack of transparency in brutality and misconduct investigations

- failure to investigate the large backlog of civilian complaints

- failure to review the policy on mass arrests (after New Bethel)

- failure to re-examine use of force policies after the police killing of an unarmed 13-year-old black male in 1969

Commissioner Murphy, who had arrived with a reputation as a reformer in his previous role with the New York Police Department, pledged to improve police-community relations and keep the promises that Mayor Cavanagh and Commissioner Spreen had broken. But in an unusual turn of events, Murphy returned to the NYPD a few months later and was replaced by John Nichols, a hardliner who came up through the DPD ranks and adamantly denied that police brutality existed at all. The DPD's relationship with the African American community seemed to be at a low point in early 1970, but it was about to get even worse.

Read documents from the Detroit Commission on Community Relation's failed efforts to reform the DPD between 1968 and 1970 in the gallery below.

Police Community Relations Project--Wrongly Blaming "Negro Attitudes" Not DPD Policies

The closest the Detroit Police Department came to acknowledging any need to "reform" came through the Police Community Relations Project Committee, established by Mayor Cavanagh in the spring of 1969 in response to the Kerner Commission Report and at the urging of the New Detroit Committee. The DPD dominated this initiative. One third of the members of the 24-person committee were either higher-up DPD officers (including future commissioner John Nichols) or leaders in the DPOA police union. The Detroit Commission on Community Relations also provided a delegate, as did the Detroit Urban League, which was the most moderate, business-oriented, and tough-on-crime civil rights group in the city. The NAACP was not represented, and neither were any of the black power organizations or more militant community-based movements. The Police Community Relations Project Committee was clearly the voice of the establishment, with the qualification that the overrepresentation of the DPD hierarchy made it considerably more conservative than even a business-dominated entity such as the New Detroit Committee. But white liberals, in particular, believed that the DPD hierarchy would have to sign off on any meaningful reforms to make them politically palatable or possible.

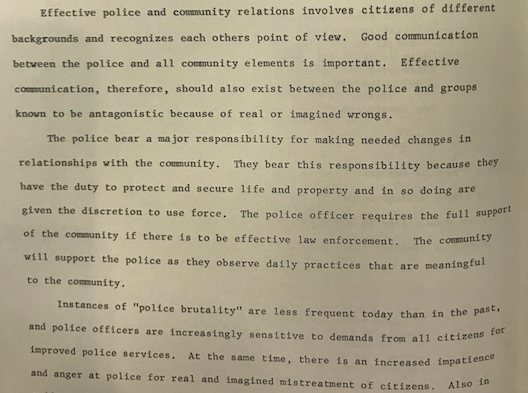

The massive Police Community Relations report, 75 pages long and released in June 1970, was an underwhelming blueprint for reform and often a vague mess, with necessary critiques softened because of the dogmatic refusal of the DPD representatives to acknowledge that either police brutality or racial discrimination in law enforcement even existed at all. Throughout, the report portrayed racial tensions between the DPD and African American neighborhoods as a communications misunderstanding or a public relations problem, often using the phrase "real or imagined" to describe the issue of police brutality against black citizens (right) and blaming the widespread African American belief in such misconduct on propaganda from Black Power militants and other so-called agitators. The report also claimed, as did Mayor Cavanagh (above), that police brutality had been a problem in the past but was much "less frequent today."

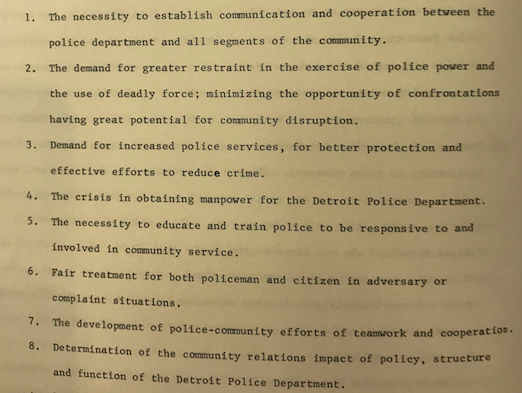

The report began with an echo of the language of Cavanagh's first police commissioner, white liberal George Edwards, in calling on the city to "build bridges of understanding between the police department and minority communities." The opening section's list of eight key tension areas (right) emphasized better communication, the need for restraint in the use of force, and the police department's responsibility to provide better crime protection in black neighborhoods. It emphasized the need to "confront longstanding grievances and antagonistic feelings"--as if the main barriers were psychological and wrapped up in black people's emotions and misunderstandings, rather than caused by get-tough militarized crackdowns and discretionary policies of racial profiling such as stop and frisk. In fact, the report called for an intensified police focus on 10-to-16-year-old males, clearly meaning African American males, part of the ongoing criminalization of black youth during this era.

The proposals that received the broadest consensus involved police professionalization, diversification of the force, and community-oriented policing. The Police Community Relations report urged the DPD to modify its hiring practices, noting that African Americans in 1969 made up 47% of the city's population and only 10% of the police department, by eliminating requirements that negatively affected black applicants and were not related to good police work. The report also called for higher salaries, recruitment of college graduates, and psychological screening combined with sensitivity training in order to better professionalize the department. To engage with communities, police officers should get out of their cars and walk the beat, while the department should enhance its voluntary civilian patrols and expand programs such as the police-youth sports league.

The report did acknowledge the need for officers to exercise better discretion and more restraint in the use of force. But the Police Community Relations Project Committee portrayed this as an issue of better training and more careful selection of officers, rather than a problem embedded in law enforcement policies themselves, with one important exception. The report recommended that the use of deadly force standard be modified so that police were not allowed to shoot based on suspicion alone (this did not happen).

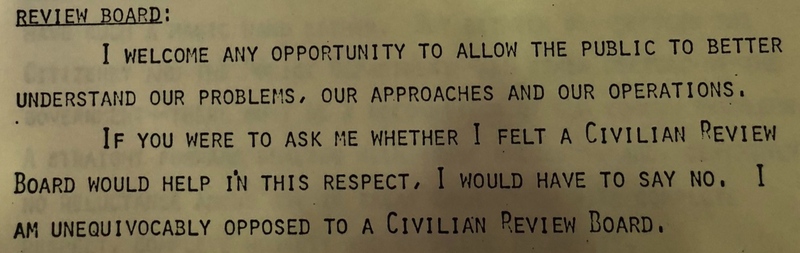

The report rejected the civil rights demand for a civilian review board in favor of recommending a more "effective" internal process through unexplained improvement of the Citizen Complaint Bureau (a few members of the committee disagreed and endorsed civilian review). The report's reasoning openly admitted that because white voters and the police department strongly opposed civilian review, it was not going to be possible in the city of Detroit. In a sentence that clearly reflected a robust internal committee debate, the report explained that the DPD and the DPOA union essentially wielded veto power over the city government on law enforcement matters:

Instead of civilian authority over the DPD, the report argued that the solution to easing community tensions would be for city officials and top police commanders to publicly and clearly insist on "equal law enforcement"--as if the exact same color-blind rhetoric had not been coming from City Hall and DPD Headquarters for more than a decade. The committee presented this report in June 1970 to Mayor Roman Gribbs and his new police commissioner John Nichols, who had been a member of the group that drafted it and who presided over the deadliest period in DPD history, except for the era of Prohibition of Alcohol, during the early 1970s.

Sources:

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Detroit Office, RG 80-17, Michigan State Archives

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

William Serrin, "How Well Does the City Police Its Police?" Detroit Free Press, July 10, 1968