4. Repression of Radicals

The Detroit Police Department launched a full-scale repression campaign against black radical organizations in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The DPD's criminalization of black radicals was part of its broader strategy of politically motivated police violence during this era, which included mass assaults on nonviolent protesters and especially on youthful African American activists. At the same time, the police crackdown on armed black militants was far more deadly, culminating in a shootout with black separatists in the Republic of New Africa in the New Bethel Incident of March 1969 and another with young African Americans in the Black Panther Party of Detroit in October 1970.

Although the DPD instigated both of these confrontations, each resulted in the death of a single police officer by an unidentified assailant, followed by the mass arrest of every black radical present on conspiracy to murder charges. The Wayne County prosecutor brought murder charges against three Republic of New Africa members in the first incident and against 15 Black Panthers in the second one, but racially integrated juries acquited them based on the complete lack of direct evidence. The DPD and county prosecutor did not, of course, investigate the rampant brutality and misconduct conducted by police officers against members of both organizations. This section tells the stories of these two high-profile confrontations between the DPD and black militants, along with an examination of the police department's expansive and illegal operation to spy on and infiltrate black radical groups.

Every urban police department in the United States took part in the violent and unconstitutional law enforcement campaign to repress black radical organizations, which took its lead from the Federal Bureau of Investigation's secret COINTELPRO operations to infiltrate and destroy black nationalist groups as well as a broad spectrum of other civil rights and New Left organizations. In 1970, the Ad-Hoc Action Group labeled the nationwide assault on the Black Panther Party "the most clear-cut manifestation of the American Police State" (right). The Ad-Hoc Action Group, which had formed to protest police brutality after the Cobo I assault on nonviolent marchers in March 1968, became increasingly radicalized over the next two years as the Detroit Police Department escalated its violence against political activists and black power groups without consequence. Mainstream civil rights leaders who did not share the black power philosophy also mobilized to defend both the Republic of New Africa and the Black Panther Party because of the extreme, preemptive violence and unconstitutional repression committed against both groups by the Detroit Police Department.

Black Radicalism and Law Enforcement Radicalism

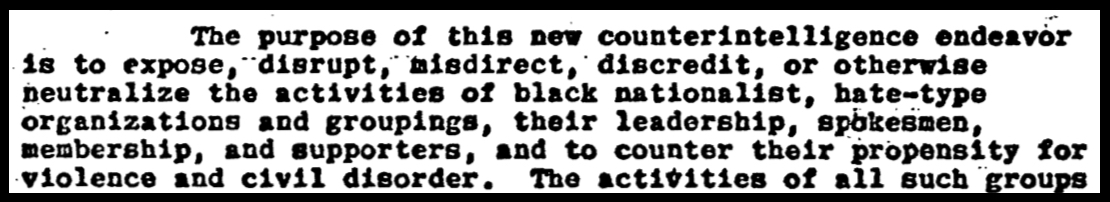

The FBI launched its COINTELPRO against "Black Nationalist-Hate Groups" on August 25, 1967, just two months after the Detroit Uprising. The top-secret operation, personally crafted by Director J. Edgar Hoover, instructed field offices to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" these organizations, ostensibly because of their advocacy of violence and civil disorder. Despite this veneer of legality, the COINTELPRO campaign was overtly political in the service of a right-wing law enforcement agenda, part of the FBI's long history of investigating "subversion" and criminalizing political dissent by mainstream civil rights groups as well as more radical organizations. The COINTELPRO launched against black nationalists even named pacifist Martin Luther King, Jr., and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference as among the"radical and violence-prone" targets (memo at left). Among many other activities, the FBI infiltrated black radical groups with undercover agents and informants through the COINTELPRO program, and these spies were often the most vocal advocates of violence, part of a deliberate strategy to justify government repression.

The FBI shared its "counterintelligence" with local police departments across the country, including the DPD, and also issued frequent updates about the violent threat of black militants and "urban guerillas" during the late 1960s and early 1970s. This includes the article at right from the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, found in the Detroit Police Department's files and titled "The Police Officer: Primary Target of the Urban Guerilla." In this hysterical alert, Director J. Edgar Hoover warns that the Black Panther Party had imported plans to assassinate police officers from Third World community revolutionaries and was orchestrating a campaign of "bitter and diabolic violence" across the United States. (The Black Panther Party actually advocated self-defense against police brutality and violence, not preemptive attacks on police). The FBI told local law enforcement that "a prime target of these revolutionaries is the ambush of or sniping at police officers." The FBI bulletin further explains that these black radical "urban guerillas" wanted to provoke the police "by acts of outrageous terror" into an overreaction that would then radicalize the urban masses and enable the overthrow of the government.

In Detroit, the police repression of black radicals built on the DPD's longstanding policies of surveillance and criminalization of African American political activists but also escalated because of the extreme racial fears and white anxieties during and after the 1967 Uprising. The Detroit Police Department, which had long operated a so-called Red Squad to spy on and repress organizations on the political left under the guise of rooting out "subversives" and preventing violence, utilized its secretive Intelligence Bureau during the 1960s to conduct surveillance and infiltration of civil rights, black power, and New Left groups. The DPD's Intelligence Bureau worked closely with a parallel politiccal surveillance unit in the Michigan State Police, and both organizations collaborated with the FBI through the various COINTELPRO programs. The DPD's illegal campaign of surveillance and preemptive repression expanded significantly in the late 1960s because of the proliferation of black power organizations in the city and the intensity of the white fear of their challenge. Recall, from the opening page of this section, Mayor Cavanagh's March 1968 speech promising that the police department would crush "extremists of the Left" and the thousands of hysterical rumors circulating in white neighborhoods that black militants planned to invade and kill women, children, and police officers.

The DPD shootout with the Republic of New Africa, which took place at the New Bethel Baptist Church in March 1969, came as the Detroit Police Department, Michigan State Police, and FBI all had the black nationalist organization under surveillance and infiltration. The DPD's yearlong campaign of harassment and brutality against teenagers and young adults in the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party revolved around constant threats by white police officers to kill its members. This culminated in a protracted police siege of the Black Panther community center, during which a single police officer died from a gunshot in unclear circumstances, with no killer ever identified. Even though two police officers died in the confrontations with the Republic of New Africa and the Black Panther Party, this violence would not have happened if the DPD had not initiated the encounters with its own campaign of preemptive violence, in alliance with the FBI and other law enforcement groups.

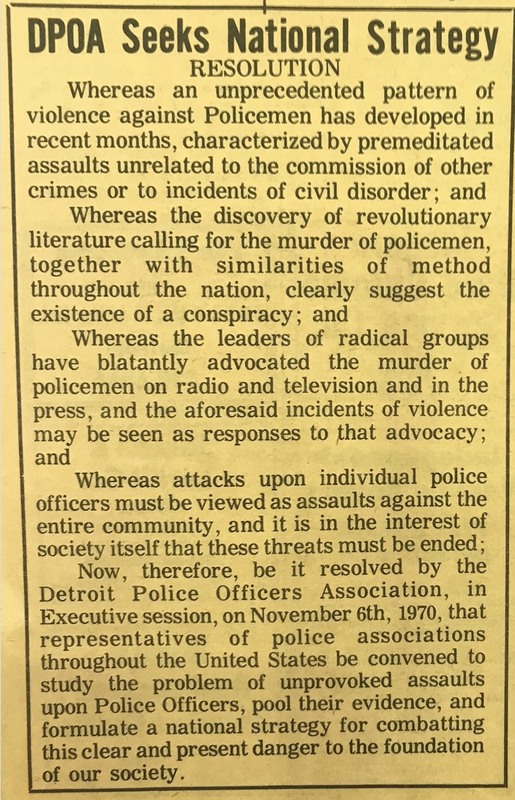

The Detroit Police Officers Association union, which emerged as a powerful right-wing political force in the late 1960s, argued constantly that officers on the street needed unregulated discretion to use force in order to control black militants and the forces of "anarchy." Carl Parsell, the union's leader, stated that any charge of police brutality, and not just an actual attack on the police, was "part of a nefarious plot by those who would like our form of government overthrown." In November 1970, after the death of a police officer in the Black Panther siege, the DPOA issued a call for a coordinated and national law enforcement strategy to counter the "premeditated assaults" on law enforcement and an alleged revolutionary black conspiracy to "murder policemen" (right). This fantastic exaggeration of the ideology and aims of black nationalist organizations stood in stark contrast to the DPOA union's argument that police brutality against black citizens was nonexistent, an argument that the DPD hierarchy also made and that even the liberal Cavanagh administration began to espouse by the late 1960s.

We generally think of radicalism as a left-wing political category that describes black power organizations, and also their white New Left counterparts, during this time period. The Detroit Police Department was also a radical and thoroughly political organization, albeit on the far right side of the spectrum. So was the Wayne County prosecutor's office, which justified every police killing of a civilian during these years and never, as clear policy, prosecuted police officers for brutality against African Americans. So was the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which criminalized political dissent on the left, rampantly violated the constitutional rights of American citizens, and encouraged and in some cases directly facilitated violence against and even police murder of black radical activists. The Detroit Police Department turned out to be at least as radical, far more violent, and definitely more criminal in its actions than the black power and black nationalist organizations that it deliberately targeted for an organized campaign of political repression.

Sources

FBI Files on Black Extremist Organizations, Part 1, ProQuest History Vault

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

"The Police Officer: Primary Target of the Urban Guerilla," FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin (Feb. 1972), 21-23

Detroit Police Officers Association, Tuebor (Nov. 1970)

William Serrin, "The DPOA: It Talks for Police," Detroit Free Press, April 20, 1969

Kenneth O'Reilly, Racial Matters: The FBI's Secret War on Black America, 1960-1972 (1991)

David Cunningham, There's Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and the FBI Counterintelligence (2005)