The Kercheval Incident, August 1966

- Alvin Harrison, Director of the Afro-American Youth Movement, to The Fifth Estate

In the mid-1960s, as confrontations between white police officers and African American citizens escalated into violent rebellions around the nation, the people of Detroit wondered whether it could happen in their city, too. In 1965, Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity Director Hubert Locke reported to his organization that the neighborhood on Detroit’s East Side bounded by Kercheval and McClellan Avenues was a “danger spot” and a possible source of racial trouble. The neighborhood was one of the poorest in the city, and its residents lacked access to adequate housing, jobs, recreational facilities, and social welfare centers. Although middle-class residents participated in one of the city's most active police-community organizations, young African American residents increasingly viewed the mostly white police department as an occupying force.

The direct-action civil rights organization the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME) formed in 1965 to confront racial inequalities on the East Side. ACME operated a community center from a storefront at 9211 Kercheval Avenue, from which it provided assistance to those who needed help finding employment, housing, and childcare. Members also protested police brutality throughout the city and accused DPD officers of persistent harassment, especially through trumped-up traffic charges and discriminatory enforcement of Detroit’s anti-loitering ordinance.

In May 1966, ACME renamed itself the Afro-American Youth Movement (AAYM), reflecting its embrace of the growing Black Power movement and paralleling its parent organization SNCC. White leaders of ACME, including Frank Joyce, formed a separate group called Friends of NSM, later renamed People Against Racism. The AAYM turned into an all-black organization led by Alvin Harrison, who had recently moved to Detroit, along with city natives including Will McClendon. Then in August 1966, police officers confronted and arrested three men for "loitering" near the ACME-AAYM headquarters, sparking four days of conflict between neighborhood residents and the police. The DPD, white city leadership, and mainstream media all agreed that the police department’s rapid response to the incident and “a fortuitous rain” prevented the conflict from spreading throughout Black Detroit. Disagreements about the root causes of the so-called Kercheval Incident, or Kercheval "Mini-Riot," revealed deep fracture lines.

What Caused the Kercheval "Mini-Riot"?

While AAYM leaders argued that police repression caused the Kercheval "Mini-Riot," in mid-1960s America, Black Power organizations often received the blame for a conspiracy to commit riot and for setting off urban civil unrest with their radical rhetoric as well as their actions. There are three main ways to think about this debate.

1. Organized resistance. In the months and weeks leading up to the Kercheval Incident, some ACME-AAYM leaders and members made statements that caused some to question whether the organization had planned the incident that set off the disturbance. For example, during the Watts Riot/Rebellion in Los Angeles in August 1965, ACME's newsletter published an editorial by Sharon Mayes that sympathized with the rioters and appeared to advocate violent resistance.

“This riot [in Watts] will be stopped, I know, and maybe it won’t win what the people want. But I say it is a good riot, well-planned and well carried-out. And if there’s one plan for nationwide activity, . . . hand me my gun. For when pickets, sit-ins, stall-ins, lay-ins, letters, prayers, and everything else can’t express our feelings enough so that the man knows we mean business then there’s no where else to turn to but violence.”

Was this statement simply rhetoric? Or did it reflect the group’s intention to incite a rebellion against the police to regain a sense of control over their community?

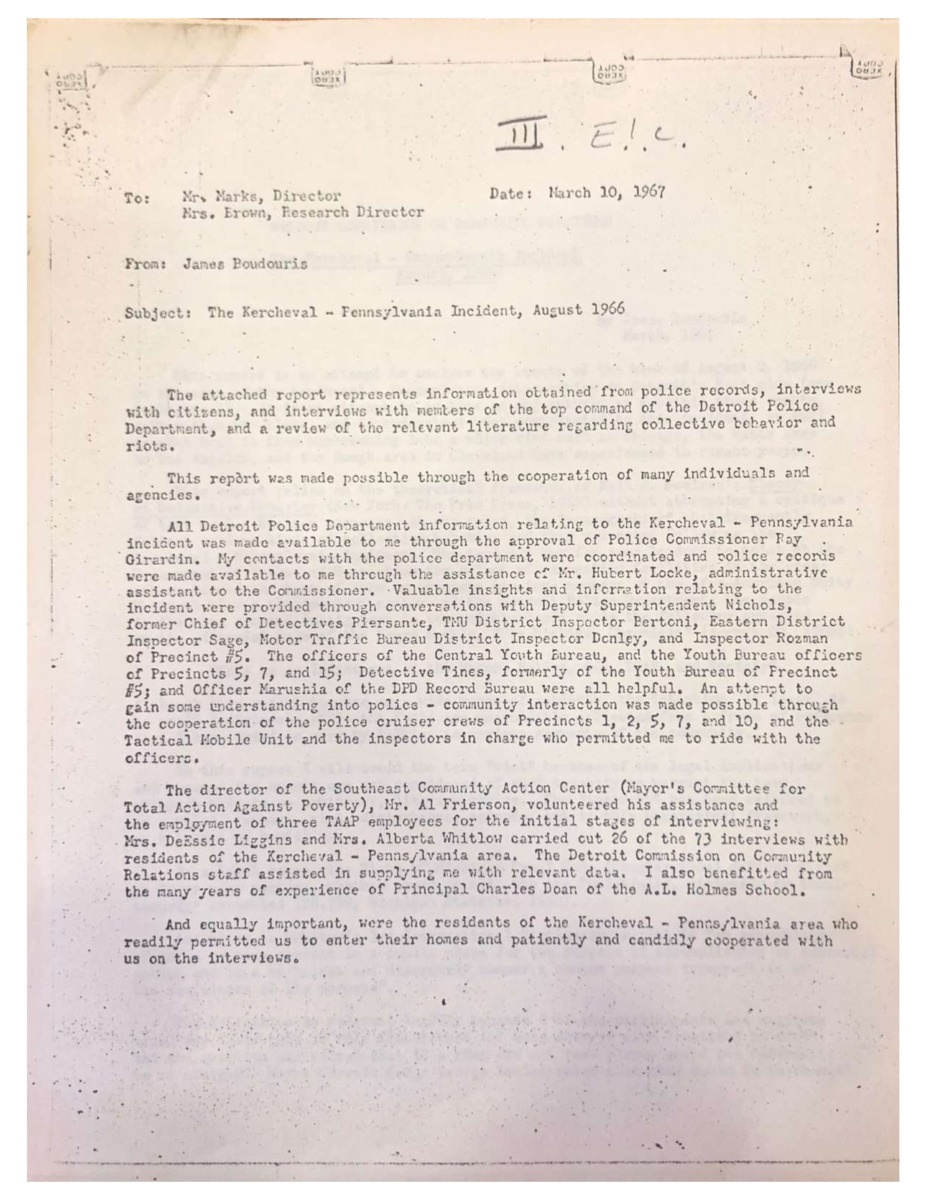

2. Planned direct-action refusal to submit to police harassment. A report on the causes of the Kercheval incident, prepared by the sociologist James Boudouris in March 1967, recounted a rumor that suggests AAYM members may have intended to escalate a confrontation with police in response to the constant harassment from the DPD. A resident told Boudouris that on August 8, 1966, the day before the Kercheval Incident began, he had overheard a group of AAYM members in a barbershop. The men gathered there after police officers threatened to ticket them for loitering on the sidewalk. According to the resident, the men decided that the next time the police asked them to disperse, they would not move. Refusing to comply with targeted police harassment is not, of course, the same thing as advocating violent resistance, but it did involve taking a calculated direct action stand against DPD oppression with the knowledge that the police would respond with force. And in Detroit in the mid-1960s, the political and media establishment generally blamed African Americans who were protesting police brutality and other forms of racial discrimination for 'instigating' conflict.

This second cause is not incompatible with the third possibility listed below. It is plausible that some AAYM members decided in advance to take a stand against police harassment, and that the DPD also anticipated and/or reacted to this trigger event with an orchestrated plan designed to frame AAYM for advocating violence as a pretext to weaken or destroy the organization.

3. DPD instigation or escalation of the conflict in order to destroy AAYM. There is a third possibility involving the role of AAYM in triggering the Kercheval Incident that is controversial and impossible to prove definitively: the belief of a number of ACME-AAYM veterans that undercover spies for the Detroit Police Department and/or the FBI had infiltrated their organization and were acting as 'agent provocateurs' to make them seem more violent than they actually were, therefore justifying police repression. Given the long history of police infiltration of radical and civil rights organizations in Detroit, this is certainly a plausible, indeed a likely, interpretation. The "Red Squads" of the DPD and the Michigan State Police had developed surveillance files on 1.4 million people by the 1970s, and local police departments including Detroit's worked closely with the FBI's COINTELPRO program to recruit African Americans as spies inside radical organizations. Often, the undercover spies would espouse the most radical-sounding rhetoric, including moving beyond Black Power's call for community self-defense into outright expressions of violence, which in turn justified police crackdowns.

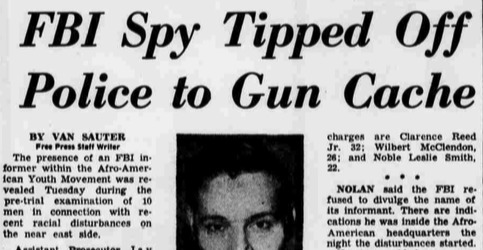

There is hard evidence that an FBI agent had infiltrated the AAYM, because the prosecutor in the post-Kercheval conspiracy trial introduced testimony obtained from the unnamed informant, and the Detroit Free Press reported the story on the front page (right). The main, unresolvable, question is what role this undercover law enforcement spy, and perhaps others, played in the Kercheval Incident itself. Indeed, ACME leader Frank Joyce told our project in a 2019 interview that looking back, he and several of the former African American leaders of ACME-AAYM who were native Detroiters believe that "probably Al Harrison is our number one suspect for being an agent.” Harrison, who arrived from nowhere and disappeared just as suddenly, and offered powerful critiques of police racism that skirted the line of open calls for violence, definitely fits the profile and pattern of an undercover agent provocateur in the 1960s. The next section on the conspiracy trial in Kercheval's aftermath provides additional evidence.

“Any black person who stands on the street corner and talks the truth is subject to being charged with inciting to riot.” - Alvin Harrison

Tuesday, August 9th, 1966

At 8:25 p.m., a Big Four police cruiser approached seven African American men standing on the sidewalk near the intersection of Kercheval and Pennsylvania Avenues. The white officers ordered them to “move on.” Four men complied, but three—a resident named Clarence Reed and two AAYM members named Wilbert McClendon and James Roberts—refused. The officers began to ticket them for loitering and asked for their identification; again, the three refused. The officers called for backup so they could take the men to the 5th Precinct station. Within minutes, two Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU) squad cars arrived at the scene, where a crowd of fifty residents had gathered. As the officers tried to put James Roberts in a cruiser, a scuffle broke out. Members of the crowd began shouting things like “Whitey is going to kill us!” “This is the start of the riot!” and “Police brutality!” Clarence Reed had been carrying a knife; in the melee, Reed and one of the officers received superficial cuts. The twelve officers on the scene subdued the three men and charged them with inciting to riot and resisting an officer. Reed was also charged with felony assault. Listen to Clarence Reed recount the start of the incident in the video on the right.

The crowd had grown to include more than 100 residents, some of whom began shouting insults at police officers and throwing bottles. Rumors circulated around the neighborhood: some swore that the police had killed a man, some said that the police had broken one of the men’s arms. 150 police officers swept the area in riot gear, armed with canisters of tear gas and bayonets mounted on their rifles. That night, crowds of young residents gathered in the area bounded by Kercheval, Jefferson, Warren, and Mack Avenues, throwing rocks at passing cars and business windows. According to the Detroit Police Department (DPD), one firebomb was thrown at a business but caused no damage. Thirteen people were injured, including four police officers, and six people were arrested.

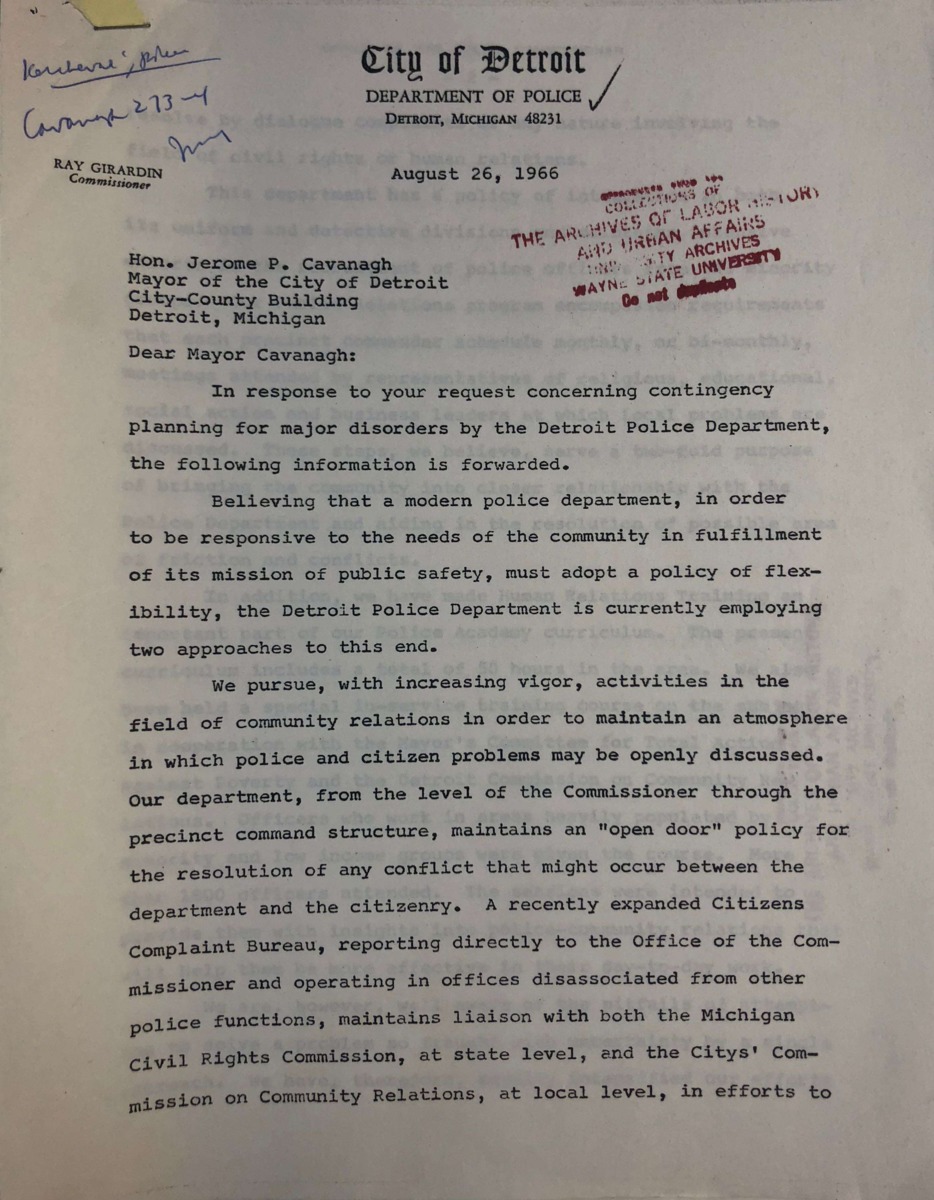

During the previous summer, the DPD had created riot-prevention plans to prepare for moments such as this one. Following these plans, Police Commissioner Ray Girardin ordered that the department convert the third floor of DPD headquarters into a command post. He placed more than half of Detroit’s police force on call, and extended officers' shifts to last twelve hours. TMU cruisers patrolled the Kercheval-Pennsylvania area in six-car units, and the mounted division, officers on horseback trained in crowd control, waited in reserve on Belle Isle in case violence spread elsewhere in the city. The DPD instructed officers to avoid making mass arrests for minor offenses and to use force sparingly.

Wednesday, August 10th, 1966

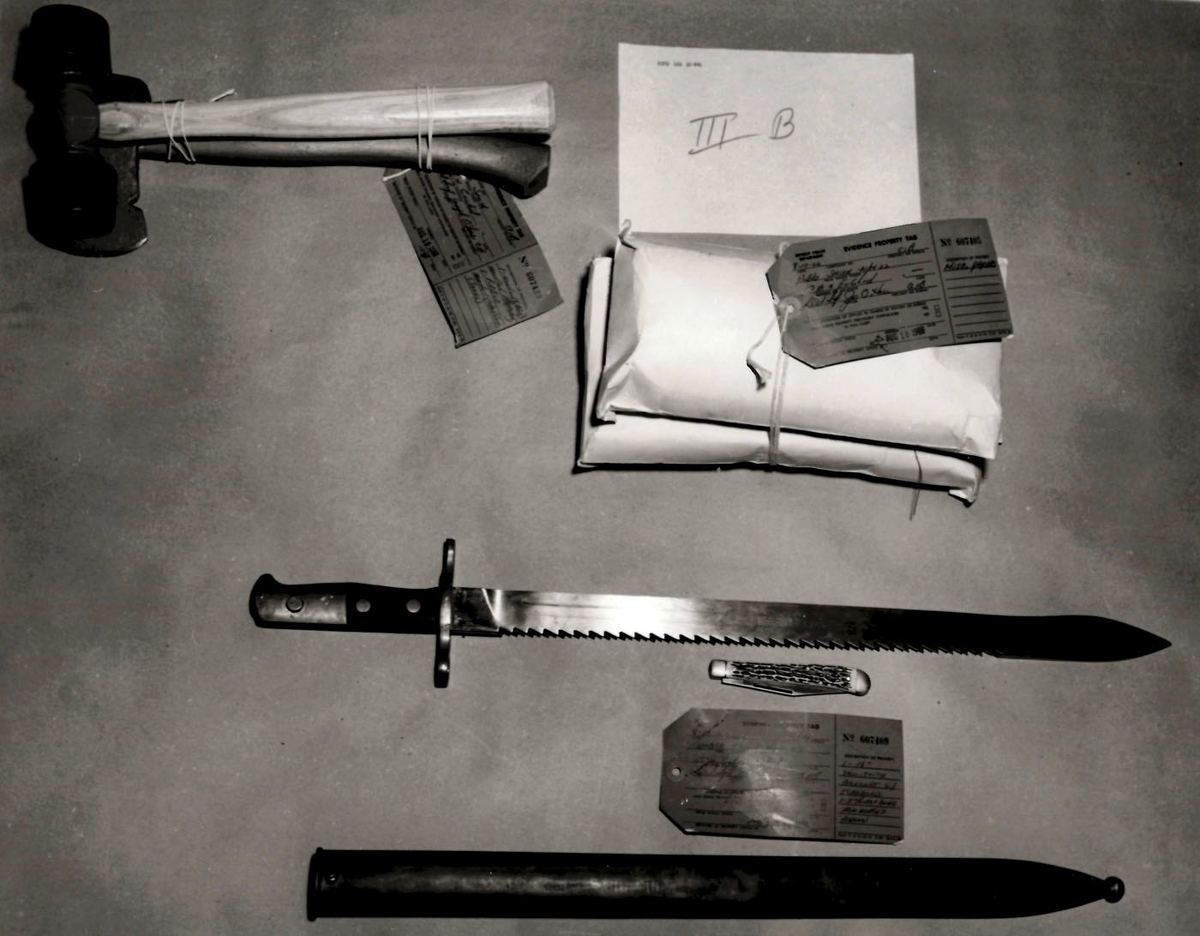

Early Wednesday morning, acting on a tip from the FBI spy inside the AAYM, officers stopped three cars leaving ACME-AAYM headquarters and discovered that they were carrying hunting knives, rifles, bricks, and ammunition. Of the four men that the police arrested for carrying concealed weapons, three were affiliated with AAYM: General Gordon Baker, Nobel Smith, and Rufus Griffin. General Baker, a well known Detroit radical, was also a leader of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and was under near constant law enforcement surveillance. In a report to Mayor Cavanagh following the incident, Commissioner Girardin reported that the DPD’s Criminal Intelligence Bureau, colloquially known as the Red Squad, had been surveilling “rabid organizations” such as the AAYM for years, leading to the apprehension of these men. (Baker and another man, Glanton Dowdell, stood trial for "carrying a dangerous weapon in a motor vehicle" and received sentences of 5 years probation). The weapons seized by the police are pictured in the gallery below and come from a display by a right-wing congressional subcommittee's investigation designed to prove that black militants had instigated the 1967 Detroit Uprising and other urban 'riots' during the mid-to-late 1960s.

On Wednesday evening, “peace patrols” composed of clergymen and block club representatives went door-to-door in the Kercheval-Pennsylvania neighborhood. Alvin "Al" Harrison, director of the AAYM, and Milton Henry, a civil rights lawyer, asked residents to stay off the streets. These peace patrols dispelled rumors and tried to calm agitated AAYM members.

Two hundred police officers in “saturation patrols” circulated through the area that night. The officers wore riot gear and covered their badges, a tactic commonly used to prevent civilians from reporting them for brutality and misconduct. TMU cars in units of six cruised through the area, and the officers inside pointed long rifles out of their windows. In the face of this overwhelming police presence, small groups of teenagers scattered around the neighborhood threw rocks and bottles, damaging cars and breaking storefront windows. Three men were arrested for throwing a Molotov cocktail and setting fire to a drugstore on Kercheval and Parkview. White youths in a passing car shot and injured a young African American man. Another fifty people were arrested that night. However, the night had ended again without major violence. The Detroit News reported that “a strong police watch and a steady, drenching rain” quenched the few minor incidents that broke out.

Weapons seized from AAYM/League of Revolutionary Black Workers activists on August 10, 1966

Thursday, August 11th, 1966

On Thursday, community leaders developed a strategy to end the disturbance. Ministers, block club representatives, Total Action Against Poverty (TAP) officials, members of the 5th precinct police-community organization, and more than 100 residents met at Saunders Memorial AME Church on Pennsylvania Street. They created a plan to control rumors and defined their roles should future incidents occur. The police department also convened a meeting with local ministers and received advice from officials from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations. The Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity reminded mass media representatives about their responsibility to prevent hysteria by reporting only the facts.

The Michigan Chronicle described the mood in the Kercheval neighborhood on the third night of the disturbance.

The heavy police presence, peace patrols, and rumor-control machinery worked. Only fifteen people were arrested; two abandoned cars were set on fire; and three Molotov cocktails were thrown, without causing major damage. Thursday night ended without any major crowd gatherings.

Friday, August 12th, 1966

On Friday, city and community leaders continued to discuss ways to end the unrest. Peace patrols made their rounds through the neighborhood, dispelling rumors and urging residents to stay indoors. From the very beginning of the incident, Detroit's major news organizations had condemned ACME-AAYM for intending to incite a riot, without seeking the organization's perspective. To contradict this narrative, Al Harrison called a press conference at ACME-AAYM headquarters and told the assembled crowd that the police officers had instigated the initial confrontation on Kercheval and Pennsylvania. He described the community’s subsequent response as “a rebellion by the black community against an oppressive situation.”

Compared to the first night, the incidents on Friday were minor. Police arrested four young white men for cursing at police officers, two white men for firing a shot into a business, and six young African American men for throwing a Molotov cocktail into a residence and causing minor damage. Again, only small crowds gathered that night and dispersed quickly.

By Monday, the unrest had subsided and Commissioner Girardin ordered the police force to return to normal duty.

The Immediate Aftermath

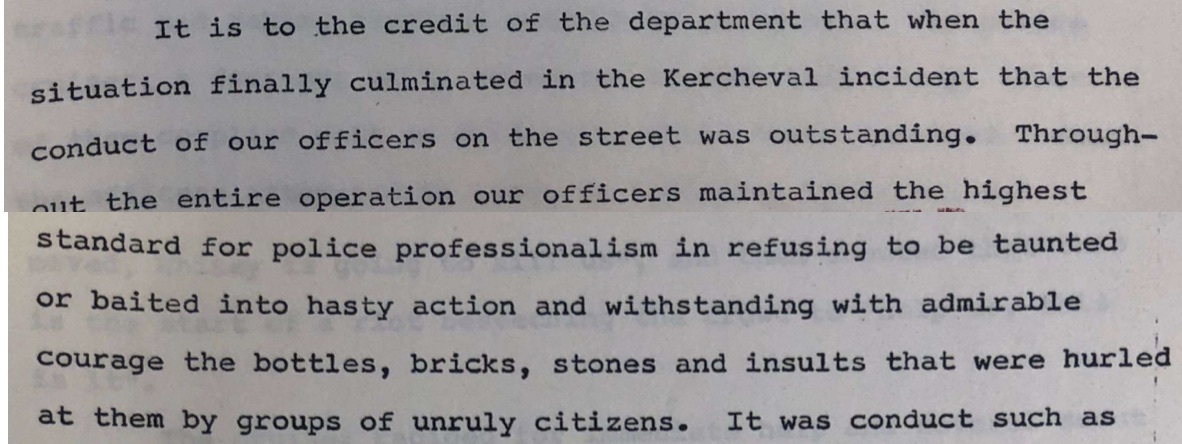

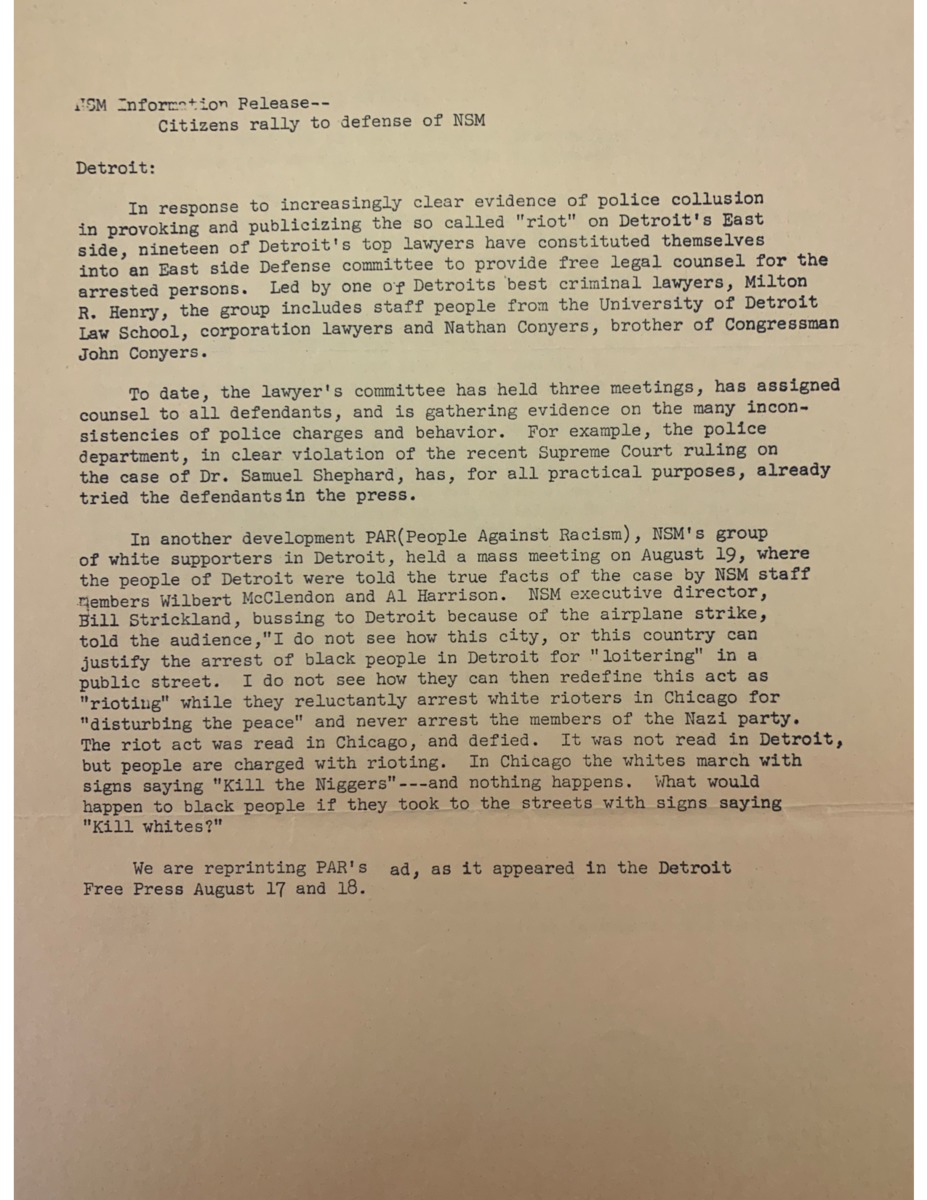

In his official Kercheval report, Girardin praised his police department for its handling of the incident. As he wrote to Mayor Cavanagh (gallery, bottom left): "Throughout the entire operation our officers maintained the highest standard for police professionalism in refusing to be taunted or baited into hasty action and withstanding with admirable courage the bottles, bricks, stones, and insults that were hurled at them by groups of unruly citizens." Girardin's report also referred to the ACME members as "known police characters," implying that they were criminals as opposed to political activists. Between August 9 and 14, the police had made 121 arrests involving 117 people, including every ACME-AAYM leader and many members of the organization. The police were only able to obtain arrest warrants for 43 of those who were detained, indicating a policy of mass arrests without probable cause as a 'riot prevention' measure. ACME and its allies assembled an East Side Defense Committee of twenty attorneys to gather evidence against the police department and provide free legal defense to the ten ACME-AAYM members who faced charges.

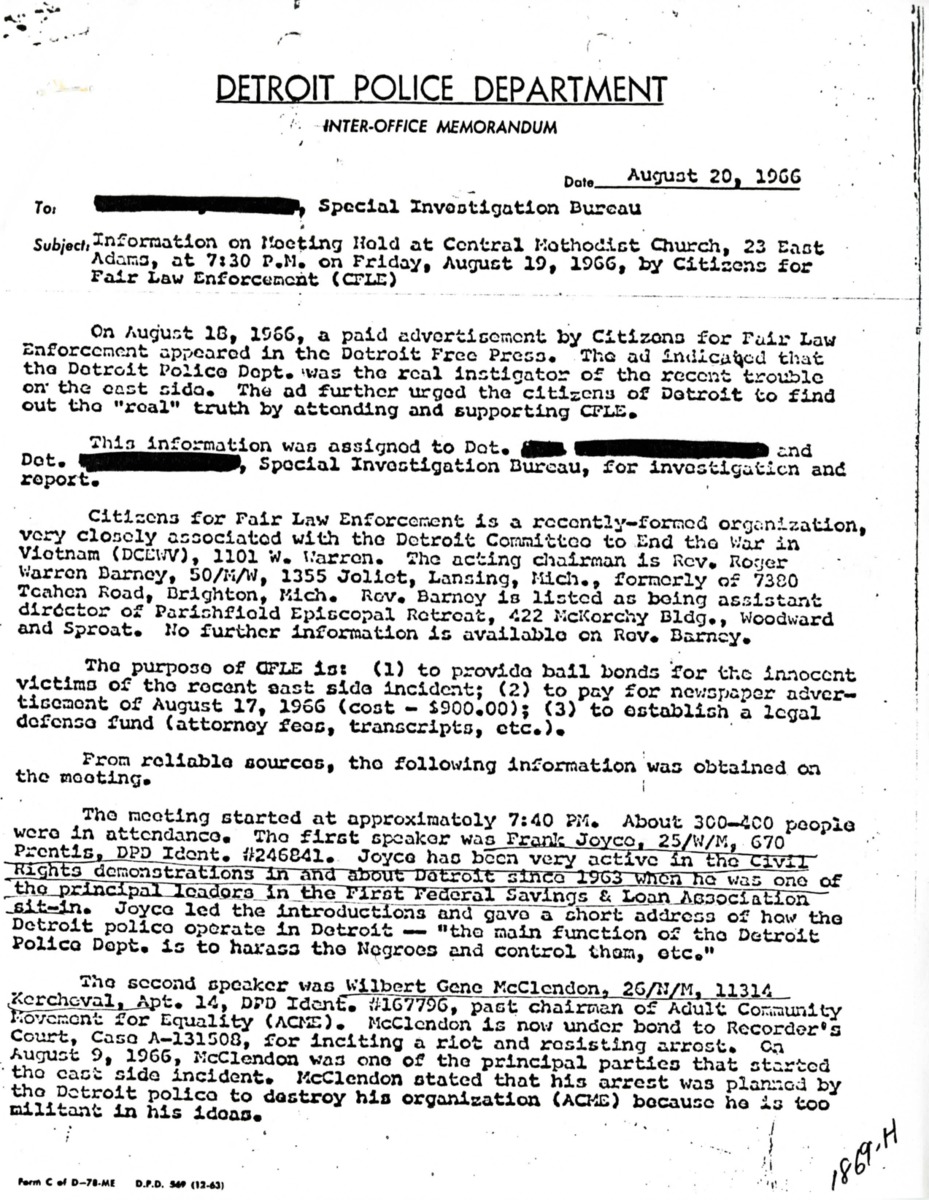

On August 19, a recently formed group called Citizens for Fair Law Enforcement (CFLE) held a meeting at the Central Methodist Church to inform the public about “the truth” of the Kercheval Incident. In an advertisement printed in the Detroit Free Press, it presented ACME-AAYM’s version of events and stated: “We are forced to conclude that the police acted in such a way as to provoke a situation which they could call a riot, which would allow them to arrest members of ACME and AAYM.” An undercover member of the Red Squad attended the public meeting and produced the report in the gallery below. More than three hundred people attended, including members of the public, reporters, and activists who were under regular surveillance such as Al Harrison, Reverend Albert Cleage, Barry Kalish, Frank Joyce, and Grace and James Boggs.

Frank Joyce opened the meeting by stating that “the main concern of the police department was to wipe out all opposition to its power,” deploying laws such as the anti-loitering ordinance "that could be used on possible technical grounds against the Negro community.” Wilbert McClendon, a former chairman of ACME who was arrested during the initial confrontation, said that the police planned the arrests to discredit ACME. “The only thing I am guilty of is standing on the corner talking to friends.” Bill Strickland, the director of the Northern Student Movement, and Al Harrison spoke about the need to embrace Black Power to overcome the police department’s oppression of African American communities. Reverend Cleage asked the audience for donations to establish a legal defense fund for those arrested in the Kercheval Incident.

In an in-depth report following the incident, sociologist James Boudouris analyzed the events of that week to determine its root causes. He observed that "the conflict seemed to be between a small segment of the Negro population and the white society in general, and specifically, its official representatives, the police force." Whichever group had initiated the confrontation, the disturbance on the East Side highlighted the poor state of the relationship between the Detroit Police Department and the African American citizens it was supposed to protect. In the aftermath of the Kercheval Incident, factions within the Detroit community disagreed about its significance and community leaders strategized to alleviate the causes of tension that it had exposed.

Frank Joyce Interview (May 2, 2019). Click to watch an 8 minute excerpt from the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab's interview with former ACME director Frank Joyce, in which he describes and analyzes the Kercheval Incident and discusses its historical legacy.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Jerome Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Michigan Chronicle

Northern Student Movement Records, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

Sidney Fine Collected Research Materials, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

The Fifth Estate

Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967. Sidney Fine. 2007.

We the People, Adult Community Movement for Equality, Northern Student Movement Records, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

Frank Joyce Interview, May 2, 2019, Grosse Pointe Park, MI, by Matthew Lassiter, Jesse Blumberg, and Jack Mahon, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_n2916388/145739741

Frank Joyce Oral History by William Winkel, 4/21/2017, Detroit Historical Society, https://detroit1967.detroithistorical.org/items/show/497