Cobo II: Defending George Wallace

Five months after the Cobo Hall assault on marchers in the Poor People's Campaign, officers in the Detroit Police Department carried out a second violent attack on nonviolent left-wing demonstrators and random bystanders at a George Wallace presidental rally held inside Cobo Hall on October 29, 1968. The influence of Cobo I on Cobo II cannot be understated. The white police who took part in the assault, emboldened by the failure of DPD Commissioner Johannes Spreen and Mayor Jerome Cavanagh to punish any officers for the violent attack on the Poor People's Campaign, operated in a "deliberate" manner "according to a pernicious plan"--according to the American Civil Liberties Union. As before, the internal DPD investigation found no wrongdoing by any Detroit police officer and instead blamed the anti-Wallace protesters for instigating the violence.

George Wallace was the former governor of Alabama who in 1963 had made the infamous promise of "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever." In 1968, he ran for president as a third-party candidate of white grievance against civil rights activists, urban rioters, and anti-Vietnam War protesters. Wallace won 10% of the vote in Michigan, and 13.5% nationwide, carrying five states in the Deep South. In 1972, Wallace won the Democratic primary in the state of Michigan during a time of extensive white backlash against court-ordered school integration. The segregationist from Alabama had a core following of working-class and middle-class white followers in Michigan, including an unknown but considerable number of white officers in the DPD, who lived in the same segregated working-class white neighborhoods that provided Wallace's strongest base of support.

The Wallace Rally Confrontation at Cobo Hall

George Wallace's late October rally in Cobo Hall was typical of his presidential campaign, and so was the presence of a committed group of young political activists, mostly white radicals affiliated with the New Left and anti-Vietnam War movements, who came downtown to protest the event. Wallace campaigned on a right-wing "law and order" platform and aggressively defended police officers against accusations of brutality during confrontations with civil rights and antiwar demonstrators. He took particular pleasure in criminalizing, and mocking, white "anarchists" and "hippies" and threatening them with violence. Wallace supporters often engaged in physical confrontations with the protesters at his rallies, as also happened in Detroit. In the video sequence at right, Wallace spars with the youthful white protesters at multiple rallies during 1968 and says that if left-wing agitators ever "lie down in front of my automobile, it will be the last thing they'll ever want to lie down in front of."

New Left activists sought direct-action confrontations, heckling and disrupting Wallace rallies across the nation and denouncing the governor as a racist and fascist. At several rallies before the one in Detroit, including Cleveland and Newark, police beat anti-Wallace protesters. And in terms of the broader political context, the violent and massed police assaults on white antiwar demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago had taken place only two months earlier, and were found to be a "police riot" in a major investigative report. Across the nation, police criminalized and deployed violence against white New Left activists during the late 1960s.

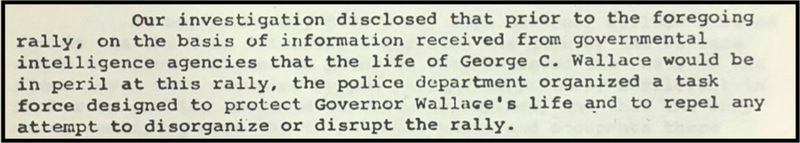

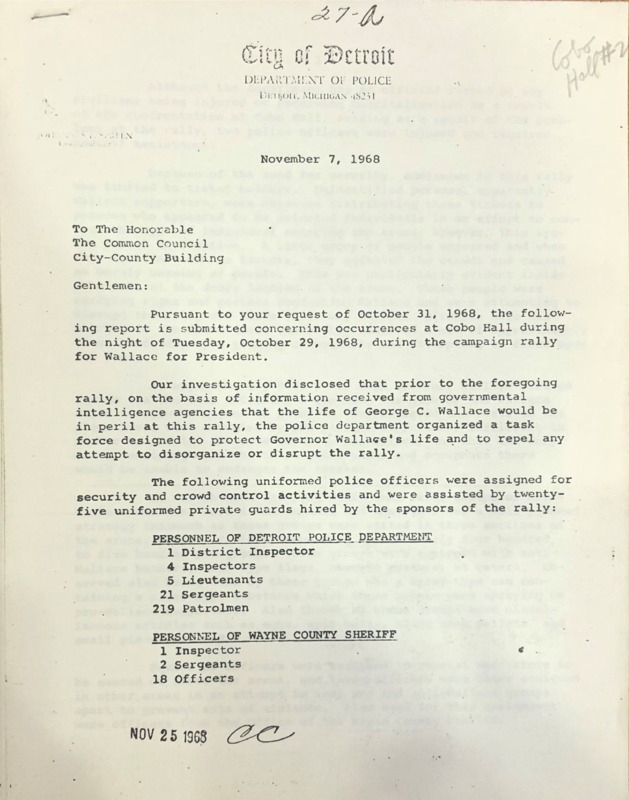

The Detroit Police Department mobilized in force on Oct. 29, deploying 250 officers on a task force specifically to protect the George Wallace rally from the anticipated left-wing protesters, many stationed inside Cobo Hall. According to newspaper and civilian accounts, there were hundreds more DPD officers in the general area, on foot and on horseback. The Wayne County Sheriff's Department contributed 21 law enforcement officials to the dedicated task force operation, and the DPD also worked with the 25-member Wallace private security team (which directly instigated violence). DPD Commissioner Johannes Spreen justified this preemptive show of force based on the alleged threat that George Wallace's life was in danger, a warning the FBI had circulated as part of its illegal COINTELPRO surveillance and disruption campaign against civil rights, black power, and antiwar organizations. The DPD task force prepared for the operation with plans to do what was necessary to "repel any attempt to disorganize or disrupt the rally."

The Wallace rally at Cobo Hall drew around 11,000 supporters and a biracial, mostly white group of around 1,000 protesters. The protesters were heckling Wallace supporters as they arrived and carrying anti-Wallace signs and posters. Protesters also were trying to get inside in order to disrupt George Wallace's speech that evening, and the police were dedicated to keeping them out. According to the DPD's version of events, which was carefully and selectively constructed to justify the later violence, an "unruly massing of people . . . were attempting to disrupt the rally and force their way inside." As the police protected the building, they confronted "a mob of approximately seven hundred people yelling obscenities and attempting to force open the doors."

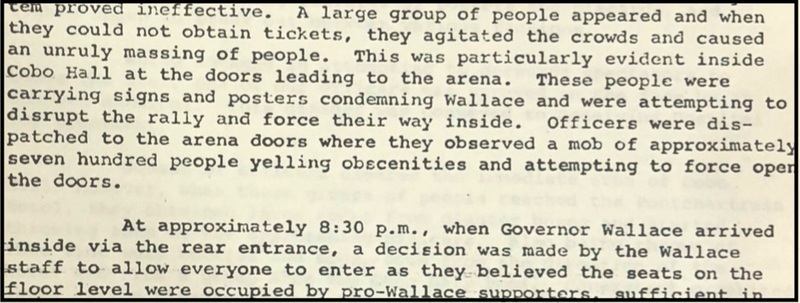

Then around 8:30 p.m., Wallace campaign staffers made the decision to open the doors to everyone who wanted to enter. The main floor of the arena was already full of pro-Wallace supporters with tickets, and the calculation was that protesters would be in the upper-level sections. But why let the "mob" trying to "disrupt" the rally in? The reason is clear, although the DPD did not acknowledge it in the after-action report (right). The Wallace campaign wanted the protesters inside, because the candidate's strategy during the string of fall 1968 rallies involved letting the hecklers shout and then baiting them back, to rile up his supporters and to portray student radicals as agitators and anarchists in the media. Physical confrontations between Wallace supporters and protesters often resulted, and the sequence of events in Cobo Hall would be no different. As the Detroit Free Press reported about the Cobo Hall event, "the former governor of Alabama . . . appeared to enjoy answering taunts of hecklers with pointed verbal barbs." Wallace told the protesters to "get a good haircut" and retorted that they were the types that "people in this country are sick and tired up putting up with."

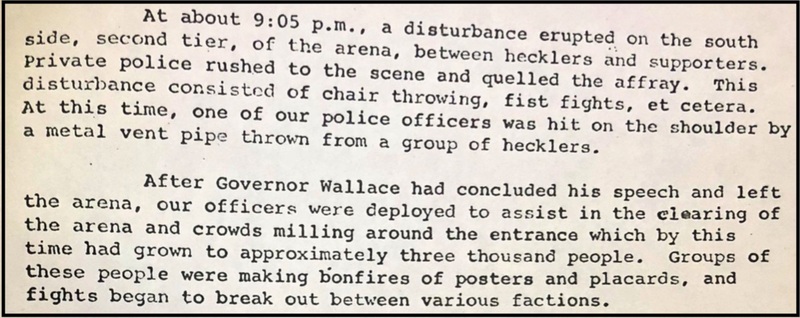

At least two brawls broke out between Wallace supporters and protesters inside Cobo Hall. The first started when a Wallace supporter, probably a member of his private security team, sprayed the chemical Mace on a heckler during the national anthem. Police forcibly removed the heckler. After that, the protesters chanted constant insults and the much larger pro-Wallace crowd drowned them out as the candidate urged them on. The second, much more violent, confrontation started when the Wallace campaign's private security guards sprayed Mace on protesters, "indiscriminately" according to the Detroit Free Press, and sought to remove a "Negro male demonstrator" who went limp and refused to leave. (The DPD's official version of events blamed the protesters for spraying Mace on Wallace supporters, which is not supported by any evidence). The private security guards alleged that the protesters were throwing spitballs at the Wallace supporters in the lower sections. Multiple fistfights broke out, and both supporters and protesters starting throwing chairs at one another. The brawl lasted about five minutes, with George Wallace watching in silence. The DPD officers and Wayne County sheriff's deputies got involved, using excessive force as a matter of course, although what actually happened inside is contested and often unclear. The worst violence came later, outside after the speech ended.

The most compelling evidence that the DPD officers deliberately planned the violent assault on a group of protesters outside Cobo Hall after the speech ended is that they removed their badges before they "cleared the area," in the euphemism deployed by DPD Commissioner Johannes Spreen (right). This maneuver, although very common among the riot police, was a violation of DPD policy and a known method of avoiding individual culpability because civilians then could not identify the specific officers who beat and brutalized them. The riot police also arrested eight protesters whom they assaulted, most for for resisting arrest or assaulting a police officer, another common and effective method for neutralizing claims of police brutality and misconduct.

The Police Charge into the Crowd

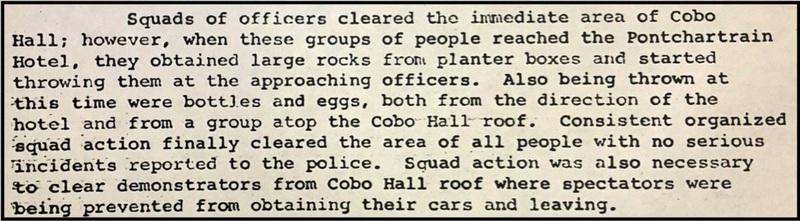

After Wallace's speech ended, around 3,000 people were gathered in various places outside the Cobo Hall entrances. The DPD officers on hand claimed that someone in the crowd sprayed an officer in the face with a chemical compound. Multiple squads of DPD officers immediately began clearing the Cobo Hall area in militarized riot control formation. What happened during this time is subject to conflicting interpretations, but it seems that the police were aggressively clearing out Wallace opponents, presumably identifiable by their youth and clothing and protest signs, but doing so indiscriminately in a mixed crowd situation and therefore occasionally also using force on Wallace supporters and other bystanders.

During this general operation, a phalanx of DPD officers charged and attacked a group of anti-Wallace protesters who had taken refuge in front of the nearby Ponchartrain Hotel, and some other people in the wrong place at the wrong time. The DPD report claimed that the crowd threw "large rocks" at the officers. If this even happened, in was done by one or two people at most. Most or all of the DPD officers first had removed their badges, indicating culpability for planned violence and a coordination of brutality. An observer from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations heard one of the officers say, "Let's get 'em." TMU riot police, and other officers, then massed and attacked the anti-Wallace protesters and some incidental bystanders in front of the Ponchartrain Hotel. Most if not all of the civilians beaten by police were white, and many were college and high school students.

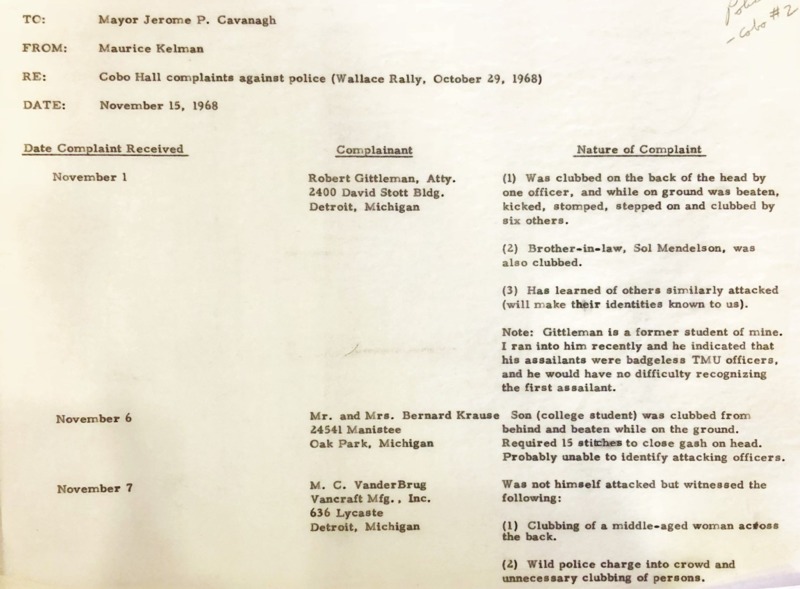

43 people filed formal complaints of police brutality, with near identical stories of being clubbed by charging police. That total represents only a fraction of the unknown number of civilians beaten by police that day. Here are 7 of their stories, some filed by parents or others who witnessed the events.

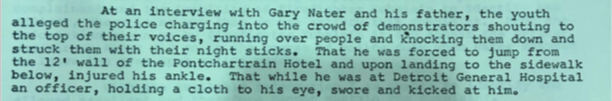

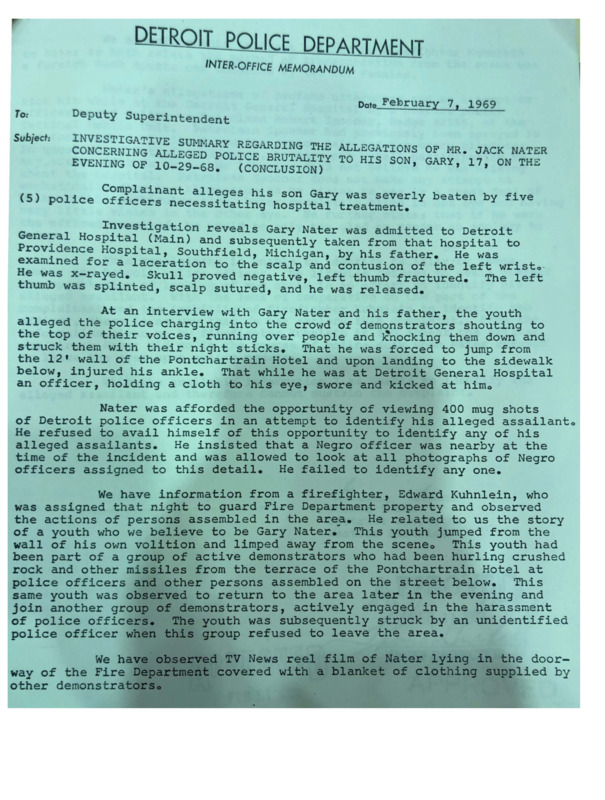

- Gary Nater, 17, was beaten by five DPD officers and treated at the hospital for a head injury. He also jumped off a ledge and injured his ankle when the TMU charged into the crowd. Nater further alleged that the DPD officer who had been sprayed with the chemical, Patrolman Robert Spooner, swore at and kicked him when they were both at Detroit General Hospital. The DPD dismissed Nater's complaint, alleging that he had thrown rocks.

- Kathleen Sixby, 16, was "clubbed on the back" while seeking to leave the scene. Her father filed the complaint.

- Son of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Krause, who was a college student, was "clubbed from behind and beaten while on the ground," requiring 15 stitches for a head wound. His parents, suburban residents, filed the complaint on his behalf.

- Edward D'Angelo, a young male, was pushed off the ledge of the hotel patio by an officer and fell fifteen feet, breaking his leg and shattering his knee. A different officer beat him while he was on the ground. He underwent surgery and was hospitalized for more than two weeks. His father, a Detroit book store owner, filed the complaint.

- Middle-aged woman and other persons reported beaten by M. C. VanderBrug of Detroit, who recount a "wild police charge into crowd and unnecessary clubbing of persons," including a friend who was knocked unconscious.

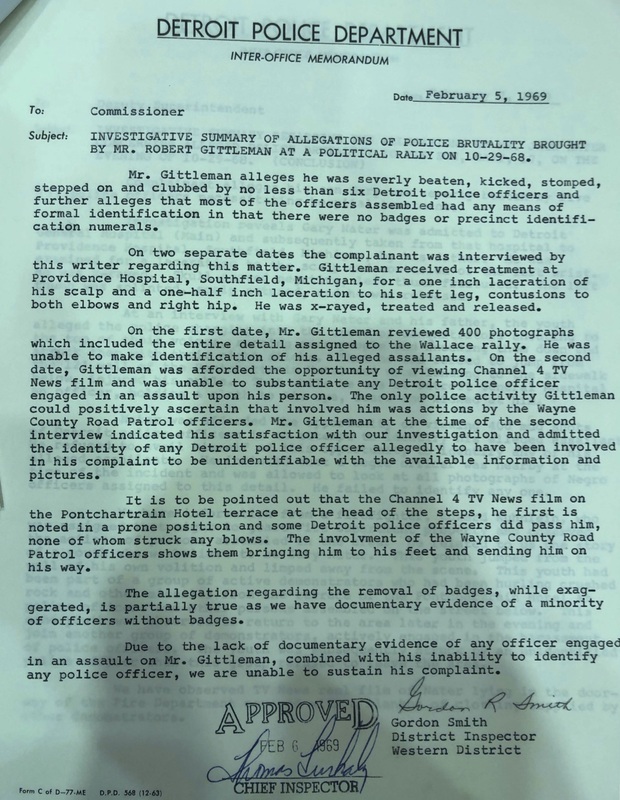

- Robert Gittleman, a Detroit attorney, was neither a protester nor a Wallace supporter and had just come to listen to the speech out of civic interest. He was walking back to his car when he was "severely beaten, kicked, stomped, stepped on, and clubbed" by six TMU officers who had removed their badges. His brother-in-law, Sol Mendelson, was clubbed by the same officers. Gittleman emphasized that "the policemen had absolutely no provocation of any kind for their primitive attack." He was treated at the hospital.

Cobo II Protests and Another Police Cover-Up

Civil liberties and New Left groups denounced the attack on the anti-Wallace crowd and demanded a full investigation. This time, most of the protests gave from majority-white organizations on the political left, reflecting the reality that most of the protesters and victims were white youth.

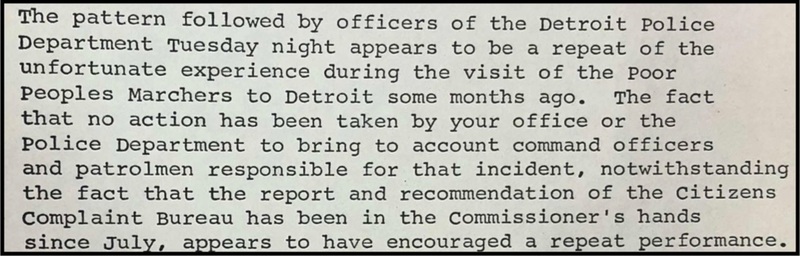

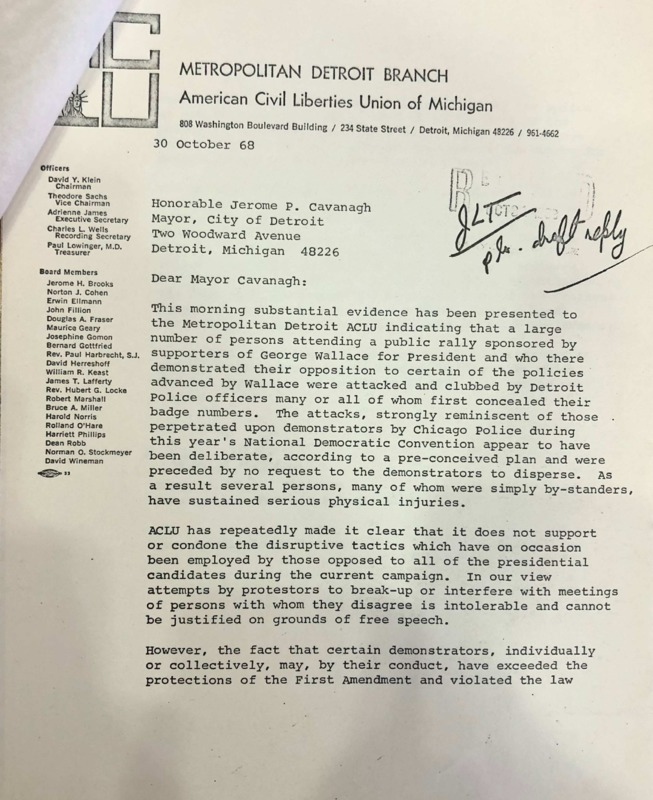

The very next day, the ACLU's Metropolitan Detroit Branch informed Mayor Cavanagh that a large number of unidentifiable police officers had attacked the anti-Wallace protesters in what seemed to be a "pre-conceived plan" of "contemporaneous retaliation" by police officers who opposed the demonstrations' political aims (below left). The ACLU likened the attack to the recent police assault on antiwar activists at the Democratic convention in Chicago and blamed the deliberate violence by officers on the DPD's failure to punish anyone for the prior assault on the Poor People's Campaign.

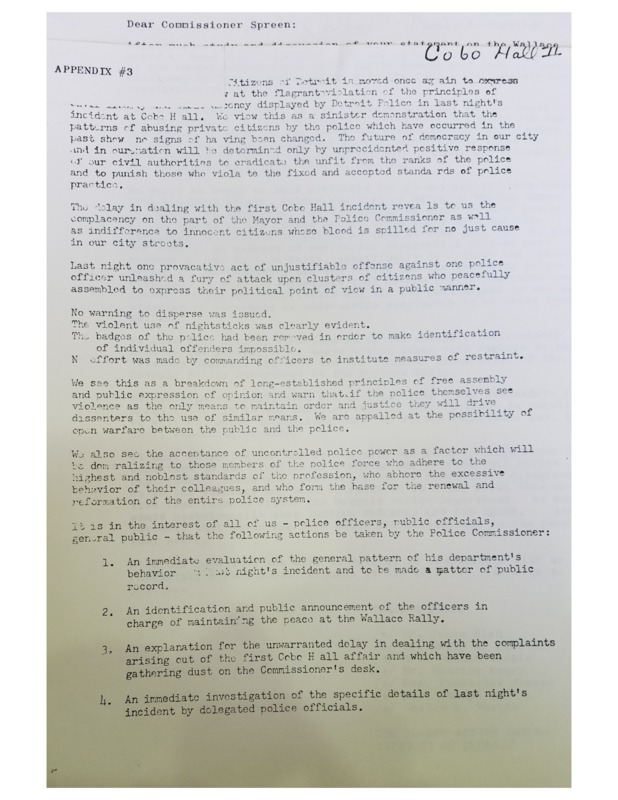

The Ad-Hoc Action Group, which had formed to protest police violence after Cobo I, also blamed the failure to punish officers after that event for the violent police impunity on display against "innocent citizens" who were exercising constitutionally protected rights at the Wallace rally. The Ad-Hoc Group's response, examined in more detail on the next page, included multiple direct-action protests at police headquarters and at the mayor's office.

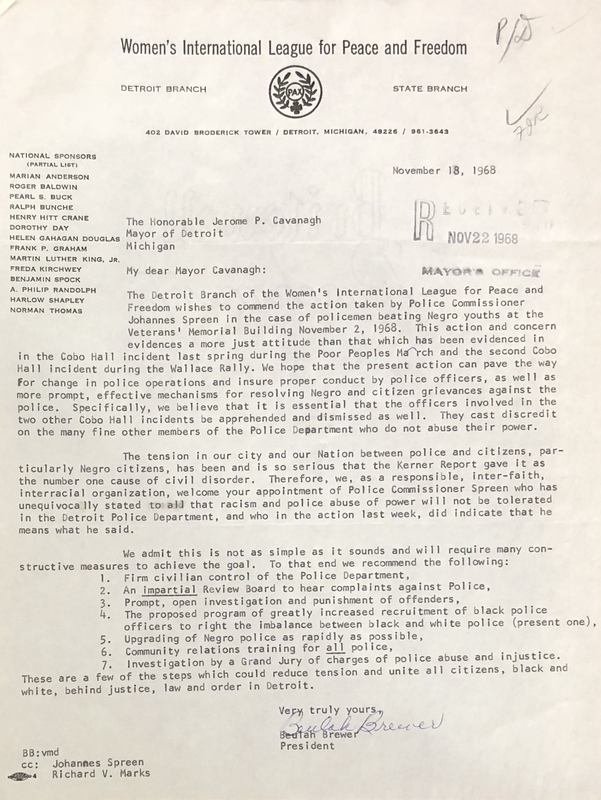

Other left-oriented groups, such as the Detroit chapter of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, similarly condemned the police violence against the white youth activists and connected it to the racist police attacks on African American teenagers at Veterans Memorial, which happened three days after the Wallace rally, and at the Poor People's Campaign at Cobo Hall (gallery below).

Commissioner Johannes Spreen whitewashed the Cobo II investigation even before it began. In his Nov. 7 report to the Common Council, reproduced above, Spreen blamed the disorderly and disruptive "mob" for everything that happened, including chemical and rock attacks on police officers, and did not even acknowledge that the police used force in clearing the crowd from the area, which he portrayed as a normal police operation. Perhaps it was.

Spreen also reported that "the department has no official record of any civilians being injured or receiving hospitalization as a result of the confrontation at Cobo Hall." At this time, at least three of the people who were beaten by police, or their parents, had filed complaints, and the ACLU had reported multiple other allegations. The DPD eventually received 43 complaints about police brutality in total.

The DPD assigned the investigation, such as it was, of the police brutality allegations to regular precinct officers rather than the Citizen Complaint Bureau. Their cursory inquiries found that the people who had filed complaints could not identify any specific officers who had assaulted them. This is not unsurprising given that the officers were decked in riot control gear, had removed their badges and other identifying information, and were moving through the crowd with frenetic violence.

The DPD officially cleared all officers involved in the Cobo II operation in March 1969. Commissioner Spreen praised the police for being "top-notch men who did a top-notch job" in keeping the peace and said there could have been a full-blown riot if the officers had not used their professional skills to control the crowd so effectively. The commissioner placed 100% of the blame on the "volatile and dangerous" anti-Wallace protesters: "those who provoke, those who intigate, those hurlers of missiles and invectives."

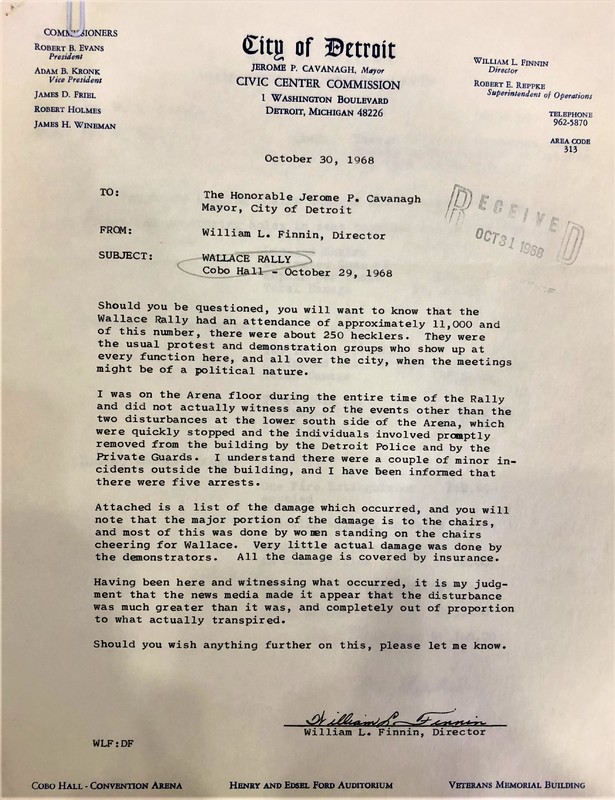

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations, which had observers at the scene of the Cobo II attack, publicly disagreed with the finding that no police misconduct had occurred. The director of the Cobo Hall convention center also informed the mayor that most of the damage inside the building had been done by Wallace supporters, not protesters, and that the media had exaggerated what really happened (below right). If nothing else, it was a blatant whitewash for the police commissioner and the DPD hierarchy to have nothing at all to say about the violation of policy by police officers who removed their badges before "clearing" the civilians from the area outside the convention center.

The DPD's de facto rules of crowd control and police use of force appeared to be: if even one person in a large crowd of political activists and/or demonstrators taunted or threw something at the police, or just if the police later asserted that someone had done such things, then whatever happened next was preemptively justified.

The Detroit Police Association Union went even further. After the Wallace rally, DPOA leader Carl Parsell said that the false charges of police brutality at both Cobo I and Cobo II were part of an anarchist plot to overthrow the government through "destruction of the effectiveness of the police." Parsell said that the police had to have the freedom to use "proper force" to maintain "peace and order."

Cobo II's most important legacy was the expansion of the biracial movement against police brutality in Detroit. Both major episodes of mass police violence against young political activists in 1968 happened downtown, with significant media exposure, at events attended by significant numbers of white people. Unlike Cobo I, where a few white antipoverty activists were caught up in the assault on black youth, Cobo II primarily featured a police assault on white New Left demonstrators. While most everyday police brutality occurred in poor black neighborhoods or along the color line, the assault on white youth at Cobo II brought an increasing number of white activists into the anti-police brutality movement and into an alliance with African American groups that had been mobilized around these issues for a much longer time. The Ad Hoc Action group, examined next, became the leading edge of this biracial movement.

Sources:

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

PBS-TV, George Wallace: Settin' the Woods on Fire (2000), https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/wallace/

Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, https://uselectionatlas.org

"Rights in Conflict," Walker Report submitted to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, Dec. 1968, http://chicago68.com/ricsumm.html

Detroit Free Press, October 25, 30, 1968, Nov. 22, 1968, March 7, 1969

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)

Edward J. Littlejohn, "Law and Police Misconduct," University of Detroit Journal OF Urban Law 58, No. 2 (1981)