Cobo I: Poor People's Campaign

During 1968, the DPD launched two unprovoked mass assaults on nonviolent civil rights activists at Cobo Hall, the convention center located downtown on the waterfront. In the first incident, on May 13, DPD mounted police and the Tactical Mobile Unit's elite "demonstration control" officers brutally attacked an interracial, majority African American, group of civil rights activists who were part of the Poor People's Campaign. The DPD falsely blamed black youth for provoking the events, and no officer was held accountable. In the second incident, on October 29, white DPD officers launched a premeditated attack on black and white activists who were protesting a rally by the segregationist presidential candidate George Wallace. Both DPD operations resulted in widespread outcry by civil rights leaders and their allies, renewed demands for fundamental transformation and civilian control of the DPD, and whitewashed internal investigations by the Citizen Complaint Bureau. The Cobo Hall incidents and DPD cover-ups, in combination with the police crackdowns on politically active youth described in the previous section, led to a powerful biracial movement against police brutality in the city of Detroit. The most important direct legacy of the first Cobo Hall assault was the formation by radical activists of the Ad-Hoc Action Group to focus community protests on police brutality.

Both Cobo incidents represent the shift after the 1967 Uprising from more individualized and discretionary incidents of police brutality against African Americans to large-scale, organized, and indiscriminate DPD assaults on entire crowds of political demonstrators. These violent law enforcement attacks on nonviolent civil rights activists mirrored the police assaults on peaceful African American protesters that took place several years earlier in Birmingham, Alabama, and other parts of the Jim Crow South, which galvanized the U.S. Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Police violence in the Jim Crow North did not have the same effect.

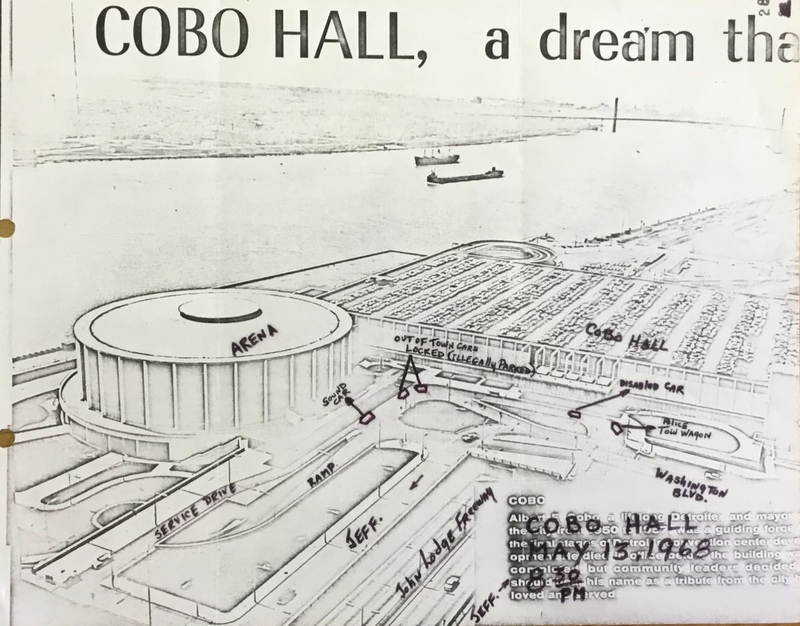

Cobo Hall, which opened in 1960, was a prominent landmark in downtown Detroit and a frequent site of political events and demonstrations. The convention center was named after Albert Cobo, the former mayor and segregationist Republican who had pledged to prevent "Negro invasions" of Detroit's white neighborhoods during the late 1940s and 1950s. In the spring of 1963, Cobo Hall was the final destination of the Walk for Freedom, the largest civil rights demonstration up to that point in American history, where the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave the Detroit version of his "I Have a Dream" speech two months before the March on Washington.

The Poor People's Campaign came to Detroit in May 1968 as part of the planned sequel, a Poor People's March on Washington sponsored by King's organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Rev. Martin Luther King was leading the Poor People's Campaign, a multiracial movement for racial and economic justice, when he was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968. The following week brought some of the worst racial unrest and urban uprisings of the decade, including declaration of a state of emergency in Detroit to prevent a "second riot" that did not in fact happen. The Midwest caravan of the Poor People's Campaign arrived in Detroit barely a month later, on the way to Washington, D.C., to demand radical economic changes to benefit all poor people in the United States.

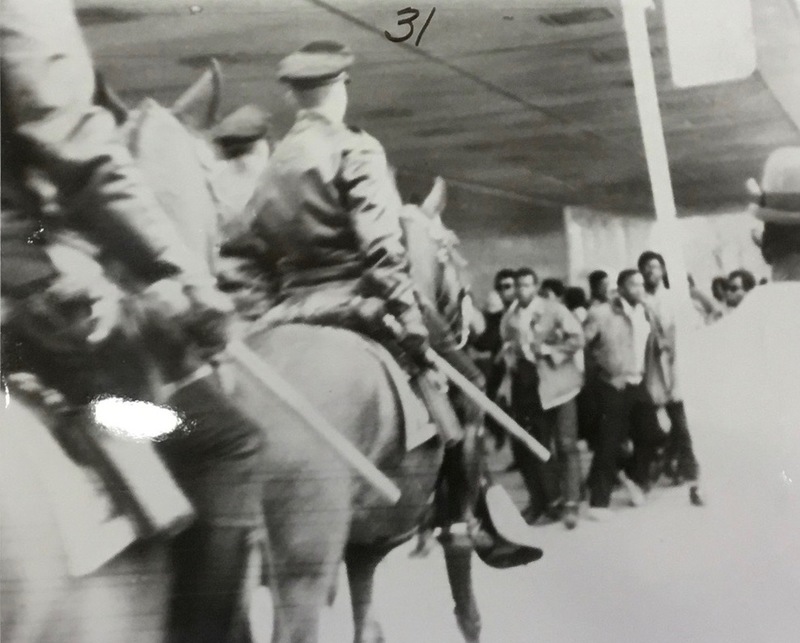

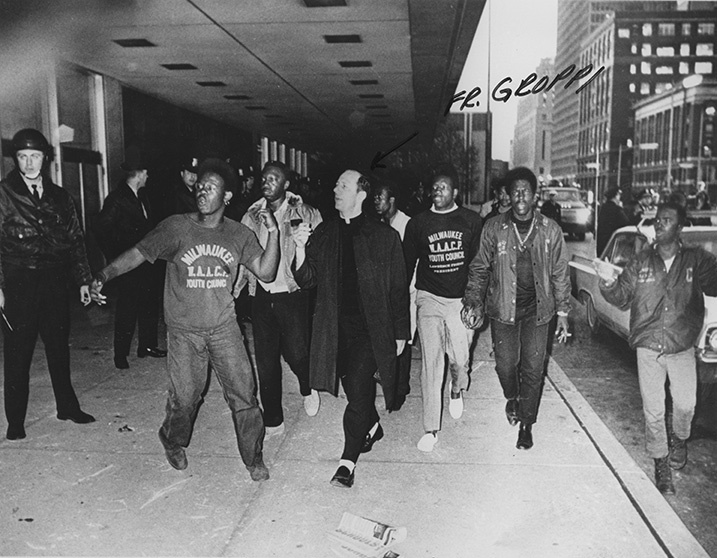

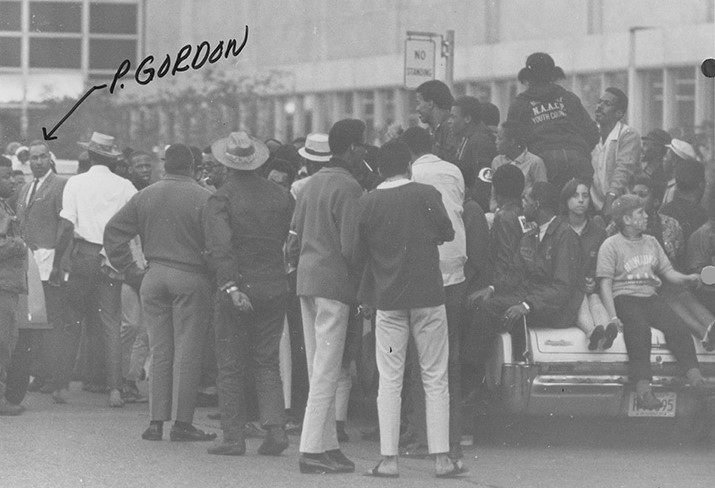

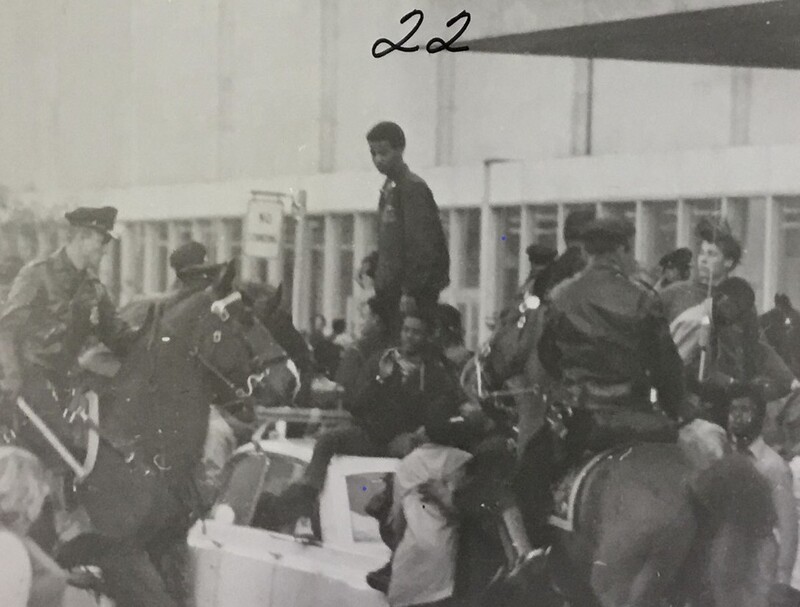

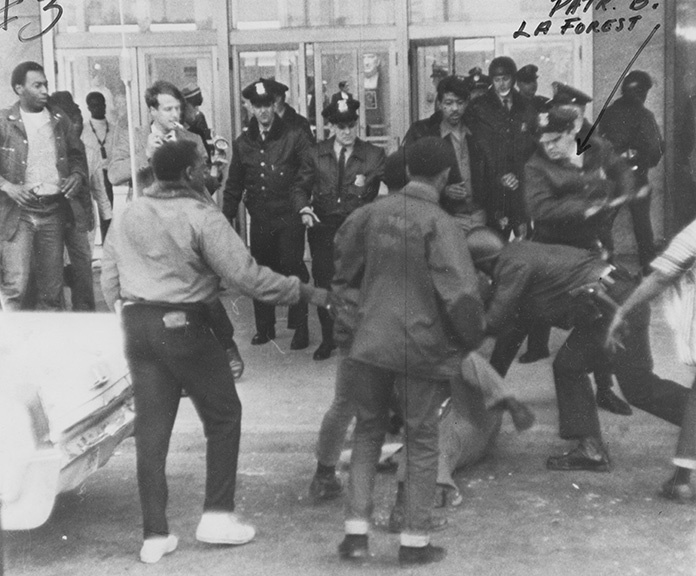

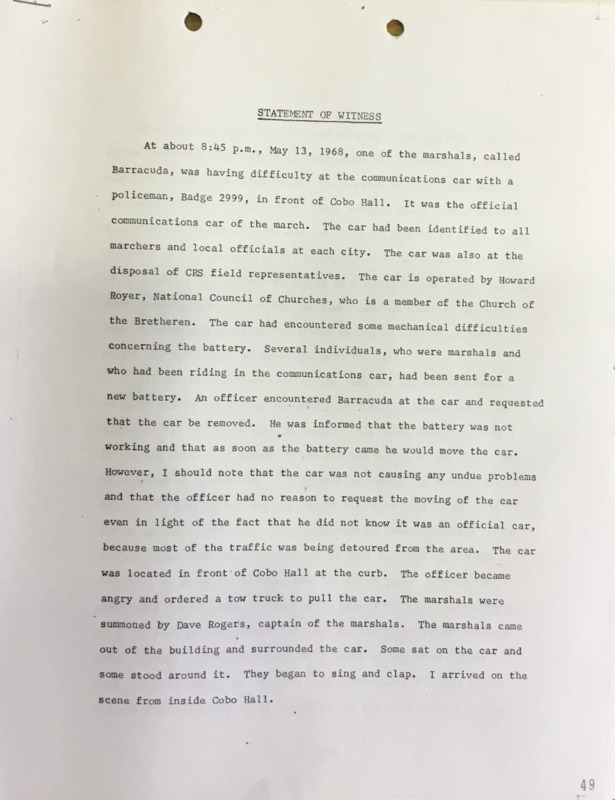

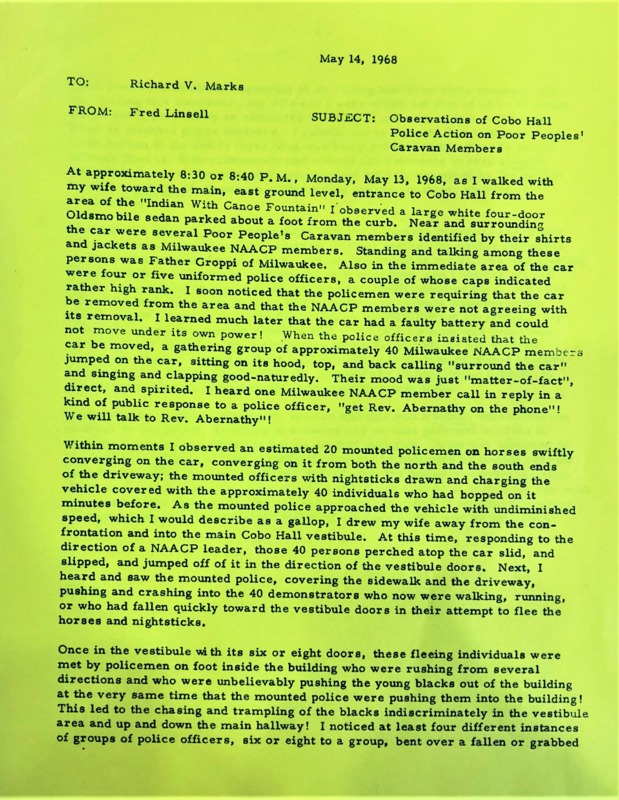

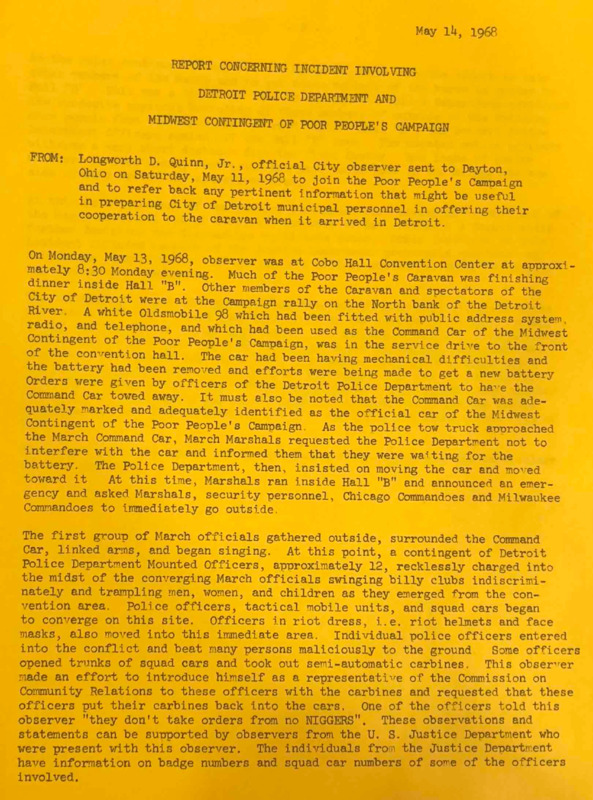

Note: The photographs on this page are marked because they were evidence in the Cobo I investigation. Some came from the U.S. Department of Justice and some from a private citizen, Edward Roberson.

The Poor People's March on Detroit

The Midwest caravan of the Poor People's Campaign that came to Detroit in May 1968 was one of nine throughout the country, gathering support as the Southern Christian Leadership Council activists and their multiracial allies converged on the nation'a capital. The leader of the Midwest Caravan was Father James Groppi, a Catholic priest from Milwaukee and a prominent white activist in the civil rights movement. By the spring of 1968, Father Groppi had led hundreds of marches into the all-white neighborhoods of Milwaukee and its suburbs to demand housing integration and a fair-housing law, and he had been arrested at least a dozen times. He also served as an advisor to the NAACP Youth Council of Milwaukee, and many of these African American youth traveled with him to Detroit (right). In total, 700 people arrived on Midwest Caravan buses, with hundreds more Detroit area residents joining them for the local march and proceedings.

Officials at all levels of government prepared for the arrival of the Poor People's Campaign in Detroit. Mayor Cavanagh personally welcomed the Midwest caravan at the Blessed Sacrament Church and provided an initial police motorcycle escort for their march down Woodward Avenue. The mayor also made Cobo Hall available for the main event for free. State senator Coleman Young and other civil rights and religious leaders from Detroit joined in the march, as did a number of African American residents and also white supporters from the city and its suburbs, especially white Catholics who were active in the Social Gospel movement that Father Groppi personified. More ominously, the U.S. Department of Justice sent two officials from its Community Relations Service to monitor and document the event. And the DPD, while publicly mobilized to protect the marchers and ensure that the event remained peaceful, also deployed hundreds of officers to monitor the event and mobilized the Tactical Mobile Unit for its overlapping missions of riot prevention, crowd control, and control of political demonstrations.

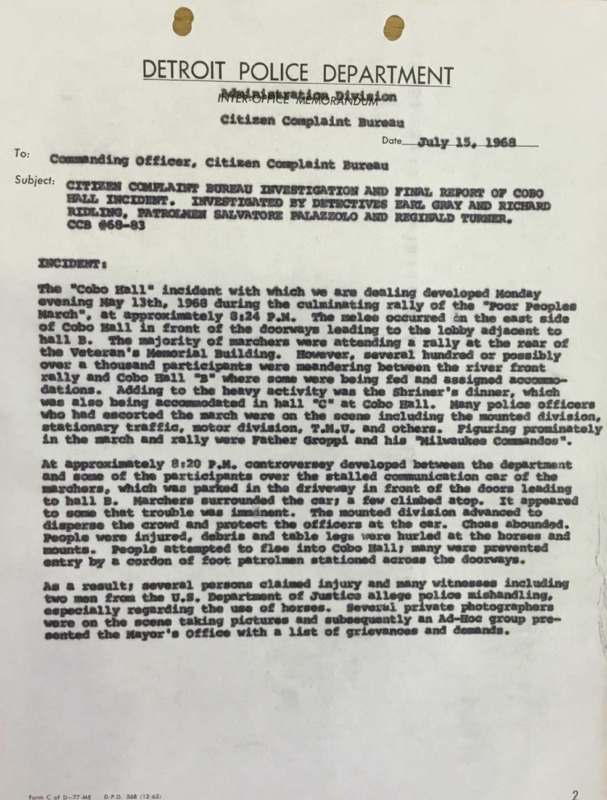

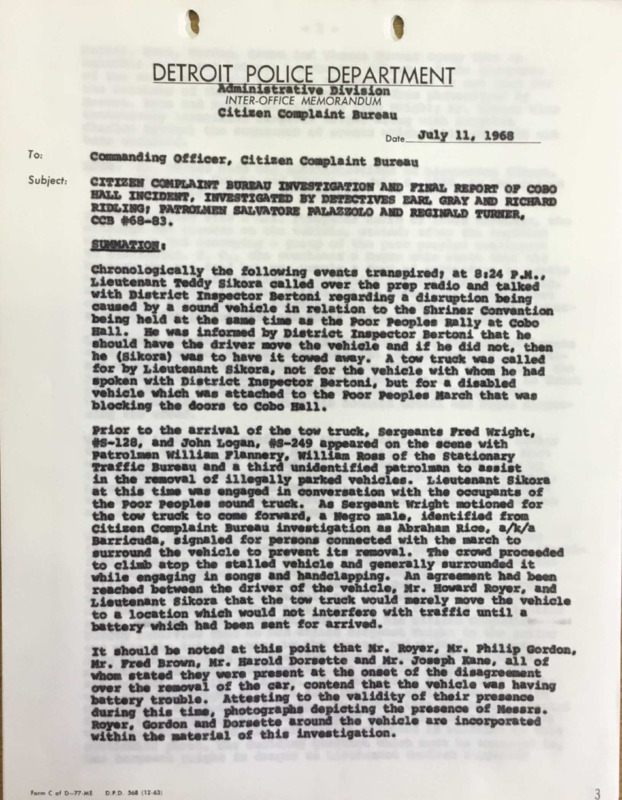

After marching down Woodward Avenue, more than one thousand activists and supporters of the Poor People's Campaign converged on Cobo Hall for the speeches and events planned inside the convention center. Then around 8:45 p.m., the official lead car from the caravan, its communications vehicle, stalled outside of the Cobo entrance. DPD officers who were on the scene for crowd control debated among themselves about whether the car was obstructing traffic or whether it could stay. Eventually Lieutenant Teddy Sikora and Sergeant Fred Wright ordered the driver, Howard Royer, to move it or be towed. Royer had dispatched a group to get a new battery for the car, and asked for a delay, but Sergeant Wright angrily escalated the situation and insisted that the vehicle be towed immediately. The marchers considered this to be police harassment of the Poor People's Campaign, since there was no traffic flow issue at the time. Howard Royer called for assistance and around forty young marshals for the Poor People's Campaign quickly arrived. Many of the youth, mostly African American but also a few white boys, climbed on top of the car and began singing and clapping. All of the witnesses described the marshalls who surrounded the car as acting in a light-hearted and "happy mood." They were seeking to prevent the police from towing the caravan's lead vehicle, but the protest was mild and peaceful (right).

Some police officers ordered the crowd of youth to get off the car and move to the curb. Other police officers from the Mounted Bureau moved in aggressively on horseback. (The police officers testified to investigators that they gave the crowd clear orders to disperse; 19 civilian or government witnesses testified that the police did not, and one civilian reported that a mounted policeman said, "let's ride them down"). At this point, Phillip Mason from the Department of Justice identified himself and showed his credentials to the DPD officers, hoping to defuse the situation. Instead, the head of the Mounted Bureau, Officer Gerlac, purposefully maneuvered his horse to stomp on the DOJ representative's foot. At this moment, around 20 members of the Mounted Bureau began to use their horses to indiscrimately push and jostle the people on the street, targeting not just the youth gathered by the car but random spectators who were outside Cobo Hall or just walking by.

What happened next was witnessed by two field representatives from the Department of Justice, three members of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, and four officers from the Citizen Complaint Bureau. All of them stated that there was "no agitation from the crowd towards the police," in the initial report of the CCB officers present. According to the DOJ monitor's account:

Fred Linsell, a civil rights investigator for the Detroit Community Relations Committee, also witnessed the police attack. In his official report (gallery below), he stated that the NAACP youth from Milwaukee were "singing and clapping good-naturedly" when the Mounted Bureau officers charged in at full gallup and began beating them with nightsticks. As the youth fled into the convention center, a group of around 50 DPD officers emerged from Cobo Hall and began attacking them as well, catching the teenagers in a pincer action with the charging police on horseback. As Linsell described:

Linsell, who was white and was there with his wife, also pointed out that the police left them alone even though they were only ten feet away from the scene, which somehow seemed both chaotic and also an operation of organized, racially targeted violence: "not one black person eluded police orders, pushing, shoving, or manhandling."

Some of the activists who were fleeing the mounted police outmaneuvered the officers charging out of the entrance and made their way toward the convention hall for safety. Patrolmen chased a number of them down and beat them inside the building with their nightsticks.

The Tactical Mobile Unit arrived on the scene as the police attack began. Instead of "riot prevention," TMU officers joined in the assault on the African American civilians and beat black youth who were gathered in the entrance area and some who were already down on the ground. Several TMU officers threatened to escalate the violence by pulling military-grade rifles from the trunk of their cars, but they returned the weapons at the desperate insistence of one of the white DOJ field representatives. Longworth Quinn, an African American investigator for the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, testified that he was the first person to ask the TMU to put down the rifles, and Badge #2229 [Patrolman John Kress] replied that "they don't take orders from no n------".

In his statement (below), Quinn recounted that the marchers around the car were singing, and then:

The police assault at Cobo Hall badly injured at least 26 people, although Police Commissioner Johannes Spreen and the internal investigation claimed that only four civilians had been hurt. The Citizen Complaint Bureau investigation took two months and, despite fierce protests from civil rights groups, resulted in no discipline for any officer, as detailed below. Read the full statements from the government witnesses in this gallery.

Protesting the Police Assault at Cobo Hall

The Midwest caravan of the Poor People's Campaign delayed its departure the next morning in order to meet with Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and demand justice. Father Groppi and the other marchers called for a full investigation and the firing of three specific officers whose badge numbers they provided. Mayor Cavanagh publicly apologized to the Poor People's Campaign and promised a prompt and thorough investigation.

Civil rights, black power, and liberal religious organizations in metropolitan Detroit mobilized in a united front and issued a collective "Statement of Protest and Demand for Action." The signatories included the NAACP and ACLU, and black nationalist organizations such as Rev. Albert Cleage's Inner City Organizing Committee, the Metropolitan Detroit Council of Churches, and suburban social justice organizations. The statement denounced the "callous racism" and "utter disregard for constitutional precepts" of the Detroit Police Department in the unprovoked attack on peaceful citizens. The coalition denounced the DPD's repeated refusal to restrain or discipline brutal officers and issued a warning, with the summer on the near horizon, that "this is the stuff of which riots are made." The coalition also flatly charged that Mayor Cavanagh had lost power over the DPD and insisted that radical steps needed to be taken to "re-establish civilian control of the Police Department."

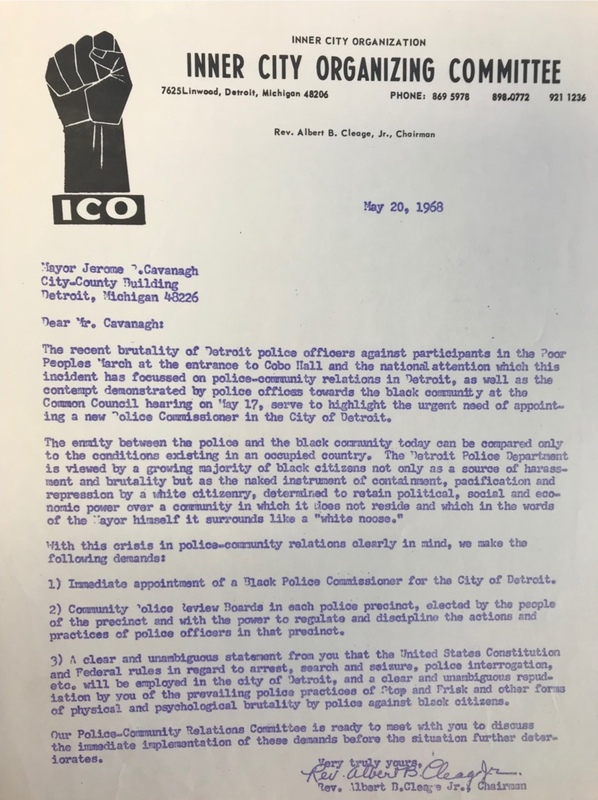

Rev. Albert Cleage issued his own demands to Mayor Cavanagh and said that police control over the black community of Detroit resembled "an occupied country." Cleage called for immediate appointment of an African American police commissioner and an elected civilian review boards in each precinct with the power to discipline and fire police officers. He also demanded that Cavanagh repudidate the DPD's stop-and-frisk policies (instead, Cavanagh signed the stop-and-frisk law less than two months later) and that the mayor clearly repudidate "physical and psychological brutality by police against black citizens." In Cleage's assessment:

Mayor Cavanagh also received protests from white residents of metropolitan Detroit who had participated in the march, especially Catholic social justice activists. Eve Walsh, a self-described "suburban housewife and mother" who lived in Farmington, attended the event with two of her teenage daughters. She described the massive police presence at Cobo Hall as completely unnecessary even before the violent attack by club-swinging, obscentity-shouting, and horse-mounted policemen. Eve Walsh told the mayor: "I was part of that nightmare scene, and the horror of it will be with me forever." She also said that most white people in the suburbs did not realize that police brutality was real, not a "manufactured claim," but she had personally experienced how "the very men who were hired to uphold law and order were themselves the oppressors and originators of violence" (above right). Eve Walsh testified about her experience in the Citizen Complaint Bureau investigation as well.

Soon after the Cobo Hall assault, white radicals in Detroit formed the Ad-Hoc Action Group to protest DPD brutality, including through direct-action confrontations. The Ad-Hoc Action Group was founded by Sheila Murphy, a young Catholic activist who worked for a community control organization in West Detroit and wanted to demonstrate white support for black power organizations and their self-determination movement. The Ad-Hoc Group demanded civilian control of the DPD and mobilized forcefully during and after the spring and summer of 1968, as described on a later page. Its emergence, and close alliance with black radical leaders, marked a turning point in the history of the struggle for racial justice and against police brutality in Detroit.

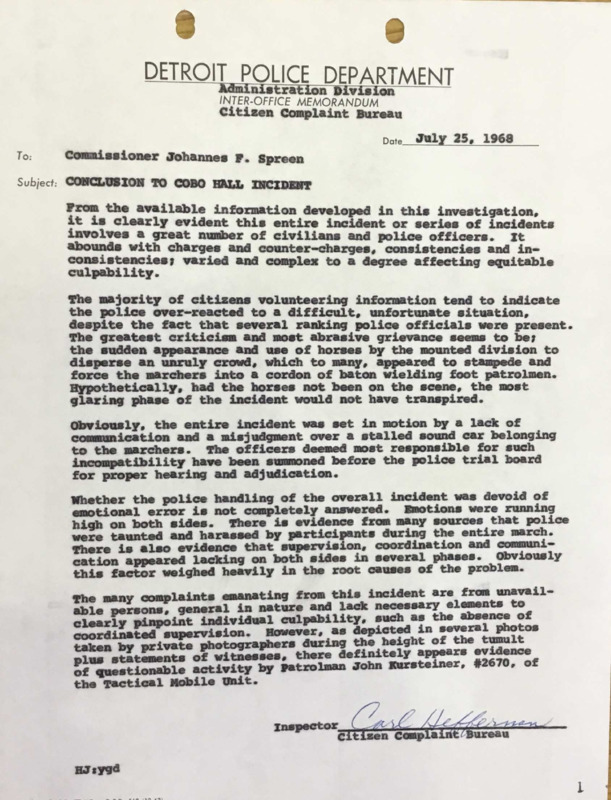

The Internal Investigation: Criminalizing the Marchers, Whitewashing the Police

The DPD initially suspended Lieutenant Teddy Sikora and Sergeant Fred Wright pending a trial board investigation for "neglect of duty." The two men were the ranking officers on the scene during the initial police assault and had escalated the confrontation by ordering the removal of the parked car. The police trial board exonerated both men and reinstated them with back pay. The trial board, led by Superintendent John Nichols, ruled that Lt. Sikora had been "helpful, courteous, and proper" at all times and that he had faced "an unpredictable and at times defiant" crowd of marchers. Commissioner Spreen promoted Sikora to inspector six months after the Cobo Hall incident.

The two-month Citizen Complaint Bureau investigation was another whitewash that criminalized the marchers from the Poor People's Campaign in order to exonerate the police department. The CCB's report (see gallery below) labeled the Cobo Hall incident a confusing and ambiguous encounter during which, citizen witnesses alleged, the police "over-reacted to a difficult, unfortunate situation." The CCB did not accept this interpretation and said "both sides" had let their "emotions" get out of control. The report deliberately criminalized and blamed the African American activists for provoking the police by making the following factual assertions and interpretations, turning the self-interested police cover stories into its framework for finding no officer guilty of wrongdoing. On a crucial question, the CCB report endorsed the police cover stories about the "unruly" crowd beside the stalled car even though four CCB officers who witnessed the incident had reported "no agitation from the crowd" in their initial recounting of the event (right).

- The CCB report alleged that many marchers had "taunted and harassed" the police throughout the day, which was not supported by any evidence except self-interested police accounts, and would not have justified the assault at any rate.

- The CCB accepted the police version that the black youth were an "unruly crowd" that needed to be dispersed--which was simply not true, according to all of the non-police witnesses, unless "unruly" is a synonym for not doing exactly what the police ordered regarding the stalled car.

- The CCB alleged, based on hearsay from a random source who was not present, that the Poor People's Campaign had faked the stalled car incident in order to create a police confrontation and get media publicity.

- The CCB portrayed the charge by the Mounted Bureau as a necessary police operation to "disperse the crowd and protect the officers at the car."

- The CCB accepted Lieutenant Gerlach's story that he ordered the police on foot to subdue the "disorderly crowd" because the marchers were threatening the safety of an officer. The investigators found that the officer was not actually in physical danger, but he was "in Lieutenant Gerlach's mind."

- The CCB considered the issue of whether Lieutenant Gerlach gave a verbal order for the crowd to disperse first before the police attack, as he claimed, to be unresolved even though 19 civilian witnesses or government monitors testified that he had not. (The CCB report did not contemplate whether Lt. Gerlach or any other officer had lied to investigators).

- The CCB report, in its opening framing, advanced the claim of many police officers that members of the crowd threw "objects and missiles" at them. Buried much later, the report acknowledged that the preponderance of evidence revealed "there was no direct physical assault toward the police officers" at the outset and that if any objects were thrown, which was unverified, it was after the mounted police rode into the crowd. (The missing analysis here, if this even happened, would be self-defense by marchers against an attack by men on horseback).

As usual, the CCB said that even if physical force did occur, the civilian witnesses could not prove "individual culpability" by any of the police officers, because of the chaos of the situation. The report stated that while the photographic evidence proved that police had nightsticks, there was no incontrovertible evidence that any officer had hit a civilian with one, except for the witness testimony that all police officers present had disputed. The report also claimed that only 4 of the 26 serious civilian injuries could be verified.

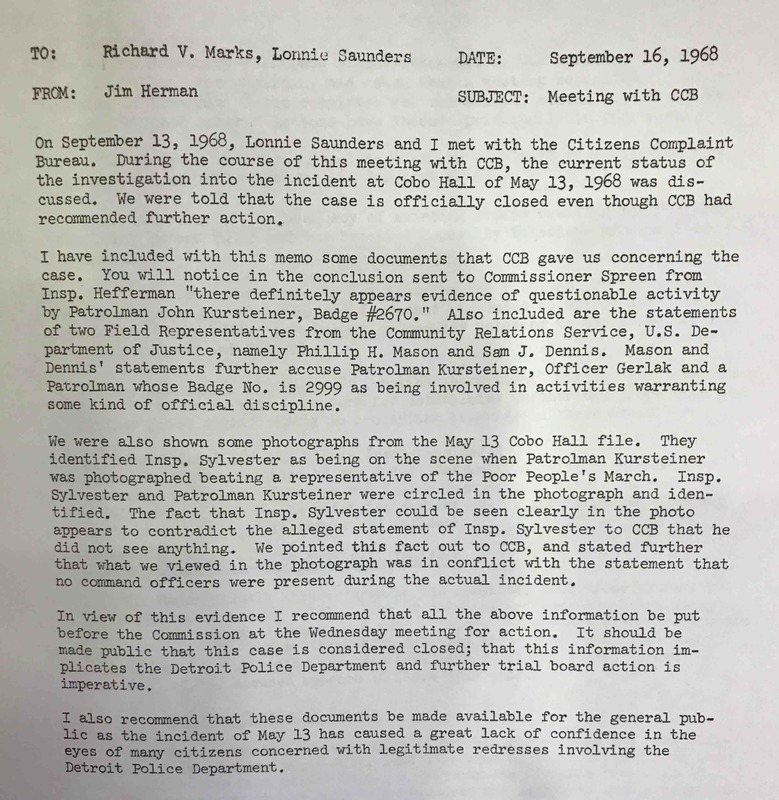

The CCB report did identify one TMU officer, John Kursteiner, as possibly involved in "questionable activity" in striking a black male teenager with a club right in front of DOJ field representative Phillip Mason, who testified to this in his witness statement (above). The evidentiary photograph at right shows Patrolman Kursteiner on the scene in riot gear. Shown this photograph, Kursteiner admitted a "physical altercation with an unidentified Negro male" but denied any other use of force. Civilian witnesses and both DOJ field investigators testified that Patrolman Kursteiner attacked many people with extreme violence during this encounter.

This photograph also shows Inspector Chester Sylvester and proves that he committed perjury in the investigation by testifying that he had not been present outside Cobo Hall and had not seen any physical force by any of the police officers under his command. (According to testimony by patrolmen, Inspecter Sylvester had given the order for the police inside Cobo Hall to move in formation against the marchers as the Mounted Bureau pushed them into the building). The photograph also shows other police officers engaged in violence, including the man kicking the marcher wearing the hat, whom the CCB investigation for some reason did not identify, even though his features are very clear. (It seems likely that the CCB did not identify this officer because no marcher had provided his badge number).

The DPD declined to take any trial board action against Patrolman Kursteiner, despite the photographic evidence of his involvement, or against Inspecter Sylvester, who clearly lied, or against any of the other police officers identified in these photographs, or against any others implicated in the testimony of multiple witnesses. The Detroit Commission on Community Relations strongly criticized this decision (below right), informing the CCB that its report had misstated the evidence in key places and ignored photographic proof that several officers had lied in their testimony to the internal investigation. The DPD informed the DCCR that "the case is officially closed."

Much later, in late November and after sustained protests by black power activists, Commissioner Spreen announced that Patrolman Kursteiner and another officer, Patrolman John Kress (marked in the above photograph) would receive internal disciplinary action of an unexplained nature for violating department regulations in the Cobo Hall incident. This was an extremely mild response, and no other officer was punished for the mass, violent assault on nonviolent civil rights marchers, including women and teenagers, with horses, nightsticks, and their fists and feet.

The CCB investigation was a cover-up, but it is also very important to emphasize that the entire premise of the investigation, based on whether individual officers had used excessive force without provocation and could be identified without doubt, distracted attention from the larger policies that caused this and other episodes of mass police violence during this era. The Cobo Hall attack resulted from the Detroit Police Department's explicit policies of militarized "crowd control" and "demonstration control" against political activists, even nonviolent and peaceful marchers, and therefore responsibility for the assault went all the way to the top of the DPD hierarchy and of the city government. Focusing too much on whether Patrolman Kursteiner should be punished, as the DCCR did, is to miss the larger policy question of why DPD officers on the scene used deliberate and collective violence against nonviolent marchers and activists.

Civil rights and black power activists understood the broader picture and made these arguments forcefully, implicating the Detroit Police Department and the Cavanagh administration for policies of racial control rather that crime control. The Ad-Hoc Action Group, which formed after the Cobo Hall assault as a direct-action protest movement against the Detroit Police Department, filed a civil lawsuit on behalf of the marchers, demanded civilian control of the DPD, and engaged in other demonstrations as detailed later in this section.

Read the CCB's investigative report and the DCCR rebuttal in the gallery below.

Sources:

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Albert B. Cleage, Jr., Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

George Romney Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

New York Times, May 15, 1968,

Detroit Free Press, July 6, 1968, November 22, 1968, November 27, 1968

Robert William Fogel, The Fourth Great Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism (2002)

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (2007)

Edward J. Littlejohn, "Law and Police Misconduct," University of Detroit Journal of Urban Law 58, No. 2 (1981)