Exposing Police Brutality and Misconduct

The Detroit Police Department has a long history of brutality and discrimination against African American citizens. Starting in 1958, the Detroit chapter of the NAACP and other civil rights groups sought to bring the issue of police brutality into mainstream politics and to expose other patterns of misconduct and illegality by the Detroit Police Department. The NAACP also joined the Detroit branch of the American Civil Liberties Union to call for an independent civilian review board, one of the main goals of the nationwide police reform movement during the civil rights era. This page highlights the exposes of DPD brutality and misconduct by the NAACP and ACLU, including firsthand accounts presented to the United States Commission on Civil Rights in its December 1960 hearings in Detroit, when Arthur Johnson and other civil rights leaders argued that police officers enforced racial segregation and white supremacy under the guise of crime control.

Investigative Arrests: A Systematic and Illegal Policy

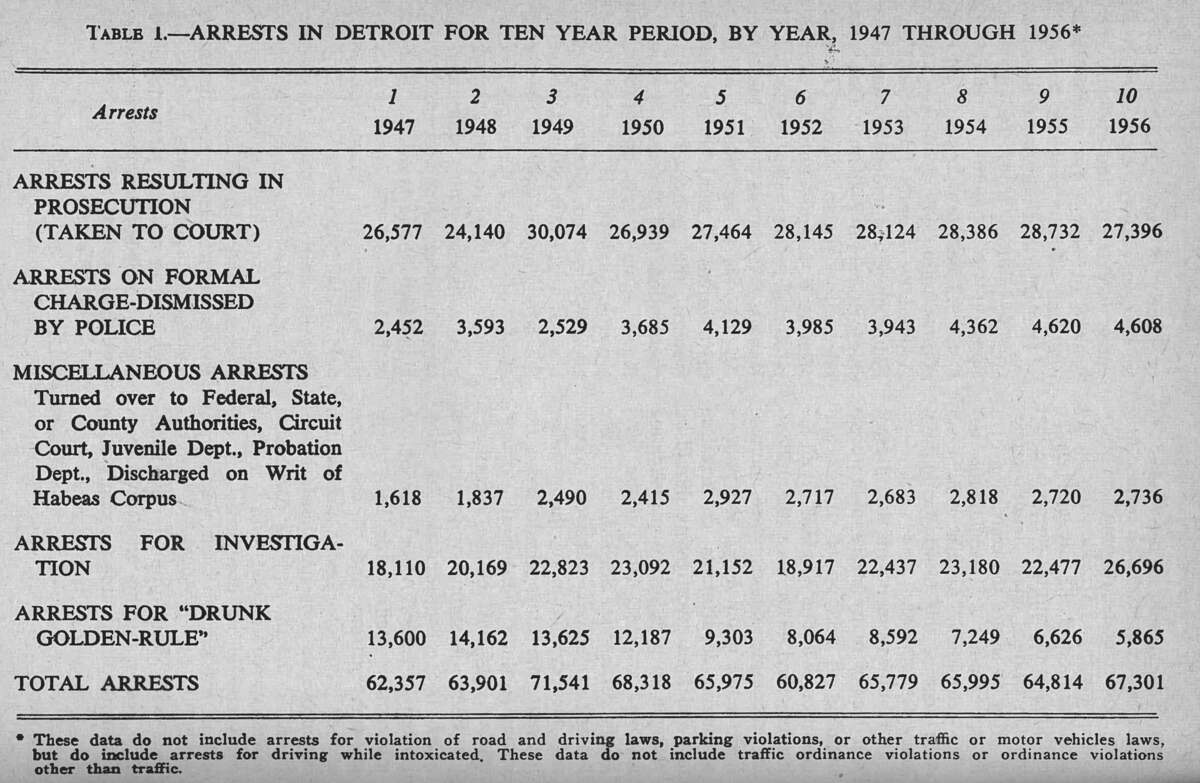

The Detroit Police Department consistently and disproportionately subjected African Americans to illegal "investigative arrests," where officers arrested allegedly suspicious people and detained them during crime investigations. In a 1958 report, "Arrests Without Warrant," Harold Norris of the Detroit branch of the ACLU documented this unjust and extensive system of investigative arrests. The report, published in the NAACP magazine The Crisis, revealed that more than one-third of all non-traffic arrests made by the DPD were warrantless arrests "for investigation only." The State Bar of Michigan had condemned the DPD practice of making investigative arrests, without probable cause, as far back as 1948. As of 1956, 26,696 out of 67,301 total non-traffic arrests were warrantless, and most did not meet the legal standard of probable cause. The ratio had been similar for the previous decade. Norris concluded:

The DPD's illegal policy of investigative arrests primarily targeted African Americans. Norris categorized their experiences as the equivalent of living in a "police state," not a democracy, where the criminal justice system deprived them of the constitutional right to "fundamental immunity to arbitrary arrest." He also criticized the local courts for not enforcing the writ of habeas corpus and allowing DPD officers to detain arrested people indefinitely. Finally, the ACLU report stated that DPD officers often tortured and abused these wrongly held prisoners in order to coerce confessions and solve "crimes." Read the full ACLU report in the gallery below:

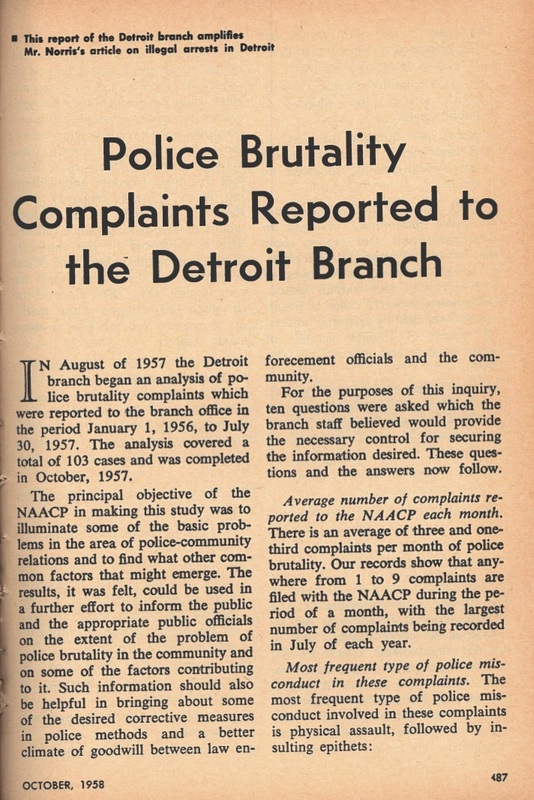

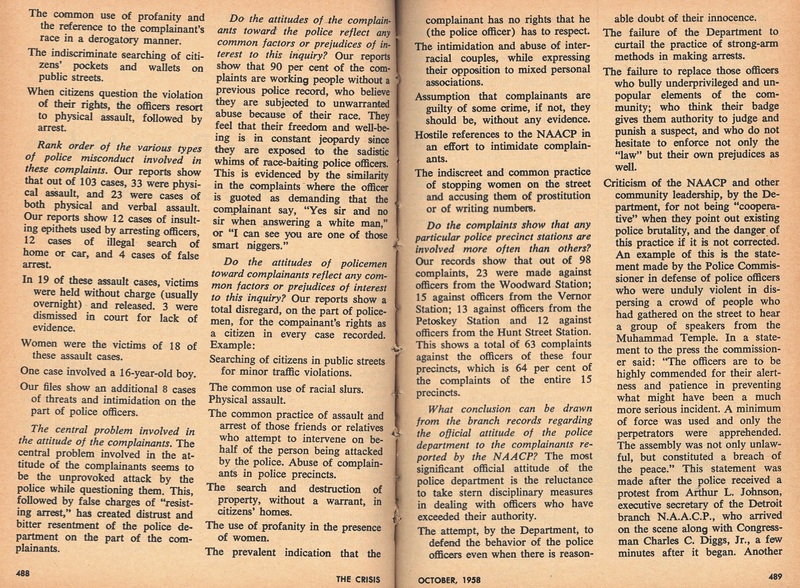

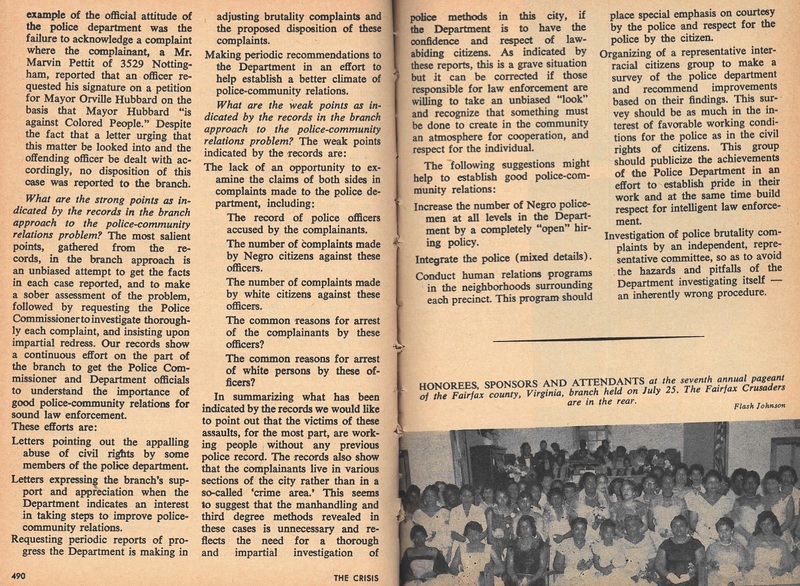

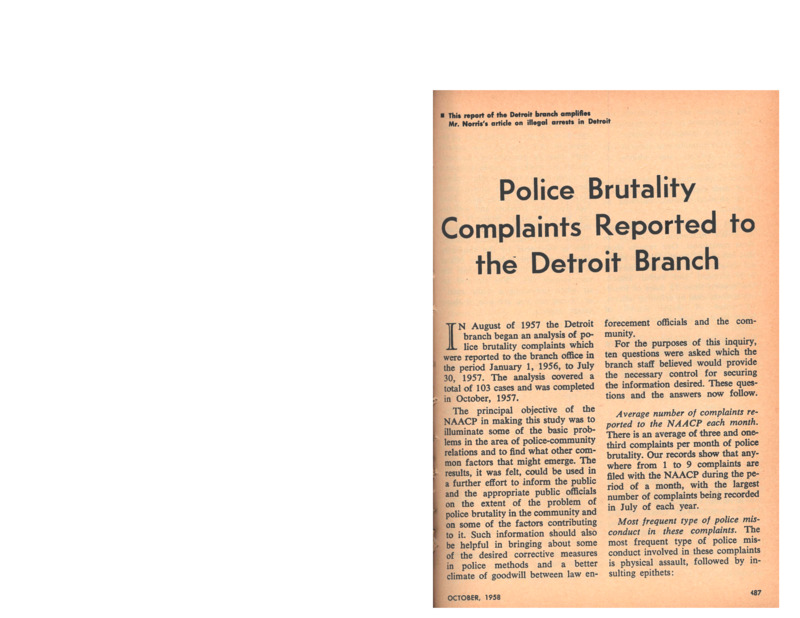

Police Brutality: The NAACP's 1958 Expose

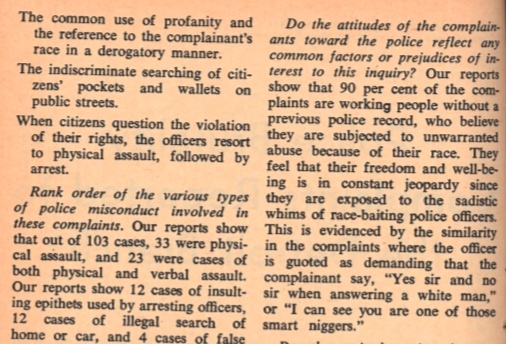

In the same October 1958 issue of The Crisis, the Detroit branch of the NAACP published the findings its investigation of police brutality and misconduct for a year and a half period from January 1956-July 1957. The report covered 103 complaints made by African American citizens to the NAACP (the Detroit Police Department did not have a formal process for civilian complaints). More than half of the allegations involved unprovoked physical assault by police officers, often in combination with racial epithets and abuse. The statistical breakdown was:

- Physical assault (33 complaints, around one-third of the total)

- Physical assault in combination with verbal abuse (23 complaints, around one-fourth of the total)

- Racial epithets/verbal abuse alone (12 complaints)

- Illegal search of home or car (12 complaints)

- False arrest (4 complaints)

Often, police officers physically assaulted African Americans after they questioned other violations of their constitutional rights, such as being stopped and searched on the street without cause (see excerpt at right). Therefore the allegations of illegal search in the chart above understate the frequency, because many complaints classified as physical assault began with a questionable or illegal search. In one-fifth of these cases, the DPD held the victim overnight without charge, which indicates a de facto policy of retaliatory arrests as well.

The NAACP emphasized that almost all complaints came from employed people with no prior criminal record--although it is important to note that black citizens in this category would have been far more likely to file a complaint with the NAACP, and so this data certainly understates the prevalence of police brutality and misconduct in the city of Detroit. The NAACP concluded of these law-abiding African American citizens:

The NAACP accused the DPD of a "total disregard" for the constitutional rights of black citizens and detailed the following patterns in the 103 complaints:

- Searches without cause after minor traffic violations

- Racial slurs

- Assault of friends or relatives who try to protect a person being attacked by police officers

- Illegal search and destruction of property in private homes

- Abuse of people wrongly arrested inside precinct stations

- Abuse and intimidation of interracial couples

- Accosting black women on the street and accusing them of being prostitutes

- Violently dispersing legal assemblies of political groups the officers dislike

- Harrassing and abusing black citizens in all parts of the city, not only in the "crime area"

The NAACP strongly criticized the Detroit Police Department for failing to investigate these allegations of officer brutality and misconduct and covering up the "appalling abuse of civil rights" by police officers. The DPD also refused to provide the disciplinary records of "those officers who bully underprivileged and unpopular elements of the community."

Based on its findings, the NAACP made five recommendations (read the full report in gallery below).

The NAACP's 1958 expose played a central role in bringing police brutality issues to the forefront of the civil rights movement in Detroit and making it clear that police violence against black citizens--like racial discrimination in housing, schools, and employment--was not just a southern issue. The report highlighted patterns of police brutality and misconduct that African Americans of all backgrounds faced daily. The Robert Mitchell case is just one example of many.

Calling for a Civilian Review Board

In 1959, the Detroit branch of the American Civil Liberties Union formally proposed the establishment of a civilian review board to investigate allegations of brutality and misconduct against the DPD. The ACLU proposal (right), sent to Mayor Louis Miriani, built on the NAACP's recommendation for an independent review board in the 1958 report on DPD brutality against black citizens. The demand for a civilian review board would remain a major priority for racial justice and civil liberties groups in Detroit throughout the civil rights era and did not come to fruition. (In 1974, after election of an African American mayor, the city established a mayor-appointed civilian board of police commissioners that lacked meaningful enforcement powers).

The ACLU proposal began with the observation that the Detroit Police Department, from Commissioner Herbert Hart on down, had demonstrated its unwillingness to discipline, or even fully and fairly investigate, allegations of brutality by police officers against black citizens. The internal Trial Board, which only rarely even investigated civilian complaints, engaged in "white-washing the police officer." Therefore only a review board of "private citizens" could do the job and protect the civil and constitutional rights of Detroit residents.

The ACLU also argued that a civilian review board would make the police department's mission of crime control more effective by increasing respect for the law and for the police in communities (meaning black neighborhoods) that currently felt "cynicism" toward law enforcement. Therefore a review board would reduce racial tensions in Detroit.

The Detroit ACLU recommended adoption of the same structure as Philadelphia's civilian review board, created in 1958 and the first ever established in an American city. In Philadelphia, the mayor appointed the civilian representatives (this would emerge as a sticking point in later years, when civil rights groups came to argue that review board members should be popularly elected). The Philadelphia board investigated all complaints brought by any party concerning police abuse, racial or religious discrimination, or a violation of state or constitutional rights. The ACLU also emphasized that the Philadelphia review board was fair to the civilians and the police officer and had upheld the civilian allegations in less than half of the cases. The Philadelphia police commissioner had adopted every recommendation by the board, and so it could not be considered anti-police.

Note: In a 2017 historical analysis, the scholar Eric Schneider argued that the civilian review board in Philadelphia was a decidedly moderate and quite ineffective response to police abuse. Because the mayor appointed the representatives, and the police commissioner had the option of rejecting its recommendations, the review board was not truly independent of city government or fully representative of the community. Schneider argued that the review board was not effective because its approach "held that the problem was an individual one, fixable through reprimands and suspensions of officers that deterred other police from committing similar offenses, and preventable by adding community relations courses to police academy training. It did not confront the essential task of policing, the unacknowledged dirty work needed to control a subjugated population, which was systemic and institutional, not individual." Because city governments utilized police departments to control black neighborhoods, Schneider argued, no reform ultimately controlled by the mayor would address the underlying causes of which police brutality was a symptom.

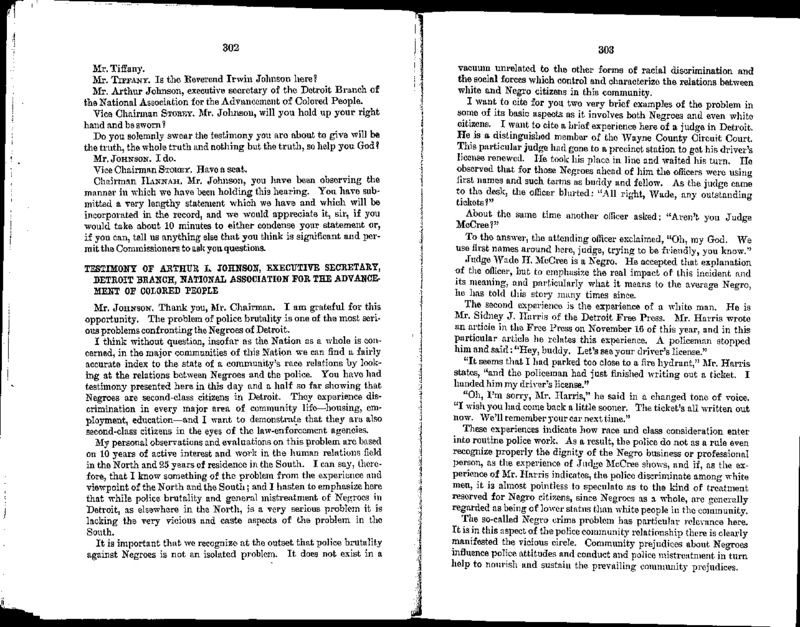

The USCCR Hearing: Exposing the Detroit Police Department

On December 14-15, 1960, the United States Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) came to Detroit as part of an investigation of racial discrimination in northern cities. During the hearings, civil rights leaders testified about racial inequality and segregation in housing, education, and employment. When the NAACP's turn came, Arthur L. Johnson, the head of the Detroit branch, focused exclusively on the "problem of police brutality," which he labeled "one of the most serious confronting Negroes of Detroit."

Johnson testified that "Negroes are second-class citizens in Detroit" in every sector of society and the economy, including law enforcement. Black residents of Detroit viewed police officers as the instruments of the white majority and its segregationist politics: "anti-Negro, anti-integration, and anti-civil rights." The DPD and the city government hyped a "Negro crime" problem in order to justify oppression and violence against black people in Detroit. Johnson emphasized that the DPD disrespected and harassed law-abiding black residents, including middle-class professionals. Johnson explained that African Americans experienced unreasonable and illegal arrests, indiscriminate and open searching of their belongings and persons on the public streets, disrespectful and profane language and derogatory references to their race and color. Police brutality almost always went unpunished, and rarely even investigated, and DPD officers often responded with violence to a civilian's protest of unequal treatment or civil liberties violations.

Johnson concluded by reiterating the NAACP's reform agenda: 1) an independent civilian review board; 2) nondiscrimination in hiring and promotion of police officers; 3) human relations training for police officers; 4) a clear commitment from the mayor and police commissioner to eliminate police brutality and other forms of mistreatment of black citizens. He also presented a sampling of police brutality cases from the NAACP's complaint files (see map below).

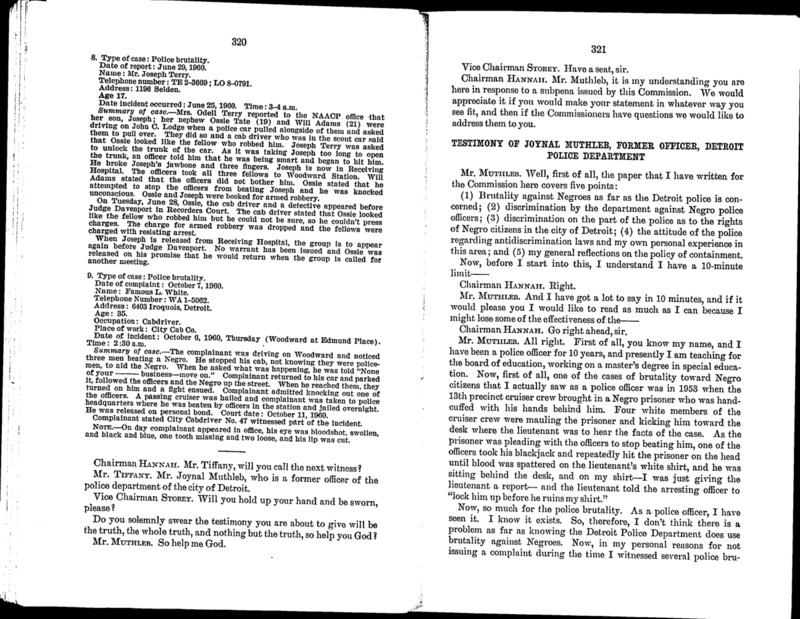

Two former African American police officers also testified to the civil rights commission. Joynal Muthleb, who served on the force from 1950-1960, told harrowing stories of police brutality toward African Americans in custody and said the white officers in the DPD operated with a police-state, "open season on Negroes" philosophy. Muthleb described an unwritten but de facto formal policy of racial profiling and illegal searches of black citizens on the streets, along with a police commitment to write black residents up for as many violations as possible while ignoring similar actions in white neighborhoods. He described the police department as hostile to basic civil rights and unwilling to enforce violations of equal protection laws in restaurants and other establishments. And he described extreme prejudice and discrimination against black officers on the force. Muthleb concluded:

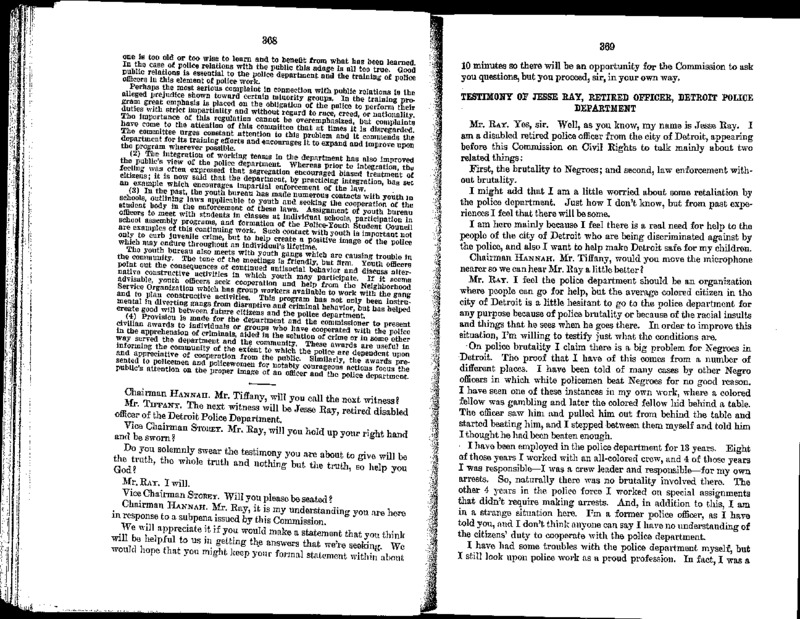

Jessie Ray, a retired police officer, told the same basic story and also stated that he feared retaliation from DPD officers for appearing before the commission. He recounted that "white policemen beat Negroes for no good reason." Twice, white officers physically assaulted Ray himself, once in uniform which left him disabled, the second when they pulled him over on the street and dragged him out of his car, choking and arresting him. In a sobering conclusion, Jessie Ray testified that as a black officer, he had never beaten or physically hurt anyone during his 13 years on the force, and that "effective law enforcement is possible without brutality."

The USCCR Hearing: Denying and Documenting Police Brutality

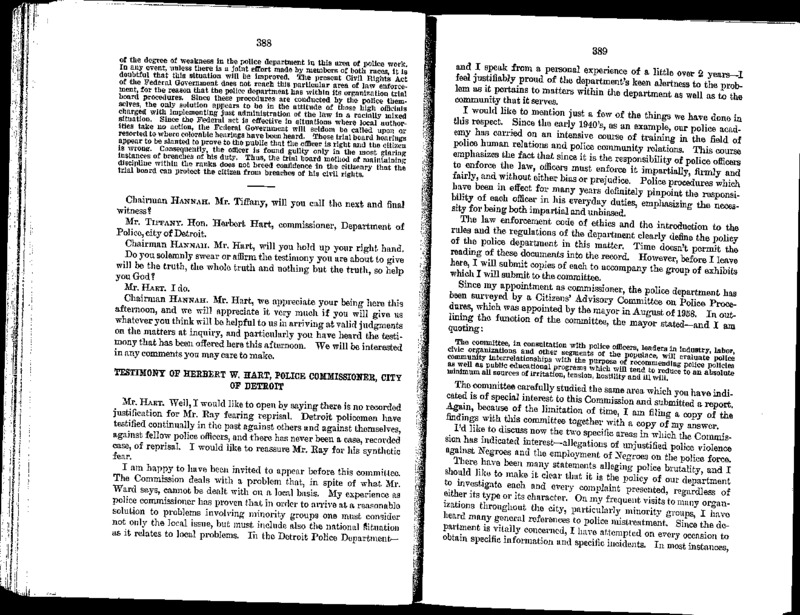

Police Commissioner Herbert Hart testified last (gallery, above right), after NAACP leader Arthur Johnson and two retired black police officers had described the DPD as a brutal, segregationist, and racist institution. Hart denied everything.

Regarding police brutality, Commissioner Hart promised that his department investigated every allegation fully and fairly. He said that in almost every case compiled by the NAACP, there was no proof and the civilian appeared to misunderstand the legal authority of police officers. He blamed this on the confusion of black migrants from the South and their inability to comprehend the "complexities of urban life." Hart stated that citizens were at fault in almost every documented use of force by a DPD officer, and that such encounters were "truly infinitesimal." Hart denied that police officers stopped and searched black citizens without cause or treated them differently from white citizens. He claimed that the DPD did not discriminate in hiring and promotion of its officers. And he strongly opposed a civilian review board to investigate allegations of brutality and misconduct. Civilian oversight was not necessary, because the DPD was effectively policing itself:

The interactive map below shows eight police brutality cases (red stars) and one police misconduct case (pink star) selected by the NAACP to highlight in detail at the USCCR hearing, out of more than 300 total complaints from 1956-1960. The blue-shaded areas are neighborhoods of primarily African American residence, and green represents the white population. Explore the incidents through the pop-up boxes and note how most took place outside of all-black neighborhoods.

Map: Police Brutality/Misconduct Cases (1958-1960) Highlighted by NAACP in USCCR Hearing

In his testimony, NAACP leader Arthur Johnson argued that the DPD carried out the segregationist agenda of the white majority and also harassed and brutalized law-abiding black citizens who had nothing to do with the "so-called 'Negro crime' problem." These complaints highlighted by the NAACP came from middle-class and solidly working-class African Americans and displayed a clear pattern of occurring in white or racially transitioning neighborhoods, or along clear racial borders between white and black parts of the city, especially along Woodward Ave. This indicates that officers in the Detroit Police Department focused on maintaining racial and social control and defending the color line through violence. The patterns also reveal that the complaints sent to the NAACP generally came from African Americans in the higher income brackets and not from residents of the poorest black neighborhoods. The absence on this map of cases from poor black areas does not mean that police brutality did not happen there but rather reflects the silences in the archive and the class politics of the NAACP.

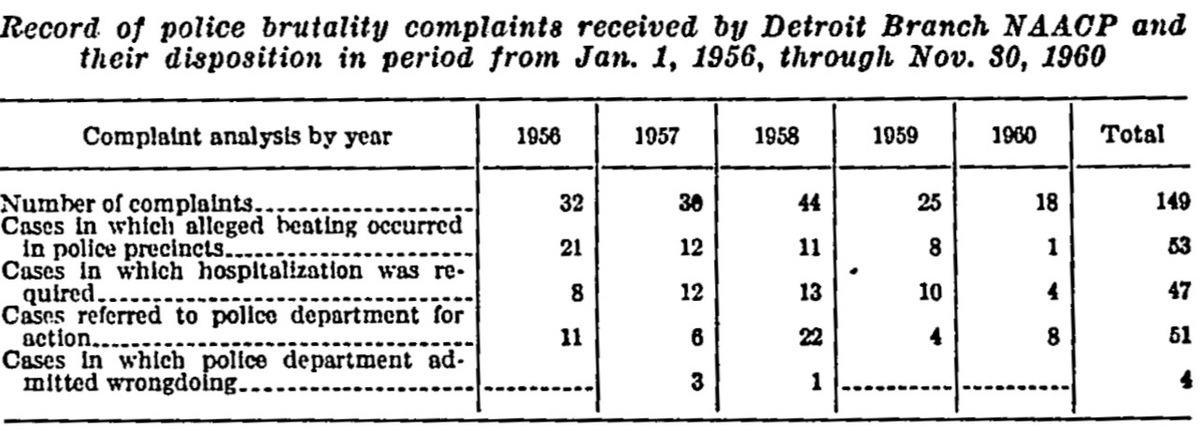

Out of more than 300 allegations compiled by the NAACP, many of which involved charges of felony assault against the police officer(s), the Detroit Police Department had found wrongdoing in only four (see graph below), with discipline restricted to a letter of reprimand. For an example of the DPD's investigative process, see the report at right from DPD commissioner Herbert Hart to the NAACP in August 1960, four months before the USCCR hearing. In these three cases, in the typical pattern, the DPD's automatic stance was to believe the denials of police brutality by police officers and assert criminality on the part of the black citizens making the allegation.

Just weeks after the USCCR hearing, in late December 1960, the DPD launched a "crash" crackdown on violent crime that included the mass arrest of 1,500 innocent African American males and that brought its tensions with the black community in Detroit to the boiling point.

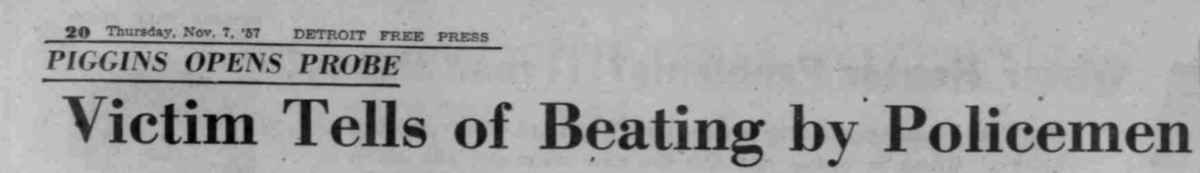

Postscript: The Paul Donovan Case

While police brutality against African Americans was systemic and part of standard police practice, it is important to note that DPD officers assaulted people of all races. For example, in 1957, police officers beat 31-year-old Paul Donovan, a white man, in a bar in a seemingly unprovoked attack. On October 27, Donovan and his wife went to a bar in Detroit. At about 2 a.m., police officers entered the bar looking for a man who had assaulted a police officer. According to Donovan, the officers asked him to leave the bar for questioning, but Donovan asked if he could be questioned inside the bar. At this request, an officer pulled Donavan off the barstool and proceeded to beat him on the floor. Police officers took Donovan into their squad car and beat him more. Then they took him to Receiving Hospital where he received treatment. The police held Donovan overnight where they interrogated him more. That night, out of fear of being beaten again and because he was dazed and confused from the trauma, Donovan pleaded guilty to a judge.

A few days later, Donovan filed an official complaint against the Detroit Police Department, resulting in a two-day hearing conducted by the police commissioner. Donovan testified that he had pleaded guilty because he was simultaneously dazed from all the beatings and terrified to be beaten again. The officers testified that Donovan tried to hit the officers first, but several witnesses who testified disagreed. Notably, Patrolman James Donovan, Paul’s brother and a police officer himself, also testified and said that he was inclined to believe both his brother and the patrolmen. Despite the testimony, the Trial Board found the officers not guilty.

The police commissioner's report argued that Donovan had pleaded guilty the first time because he was in fact guilty. The commissioner did not believe that Donovan was afraid of being beaten again and argued that his explanation of being “dazed” was not true because hospital workers had said Donovan seemed calm and mentally stable in the hospital following the beating. The report also downplayed the severity of Donovan's injuries and cited his history of getting into bar fights and the fact that he was drinking alcohol that night. The report found the officers' stories to be credible.

In its conclusion, the commissioner's report emphasized the many positive contributions made by the DPD and the dangers that police officers faced every day. The report found: "No fair minded hearing officer, basing his judgment upon the facts as presented in this case, could conclude that the officers accused acted wantonly or maliciously. A complete and thorough review of all the testimony, and a fair appraisal of all significant facts, indicate that the accused officers did not exercise improper judgment or the use of excessive force."

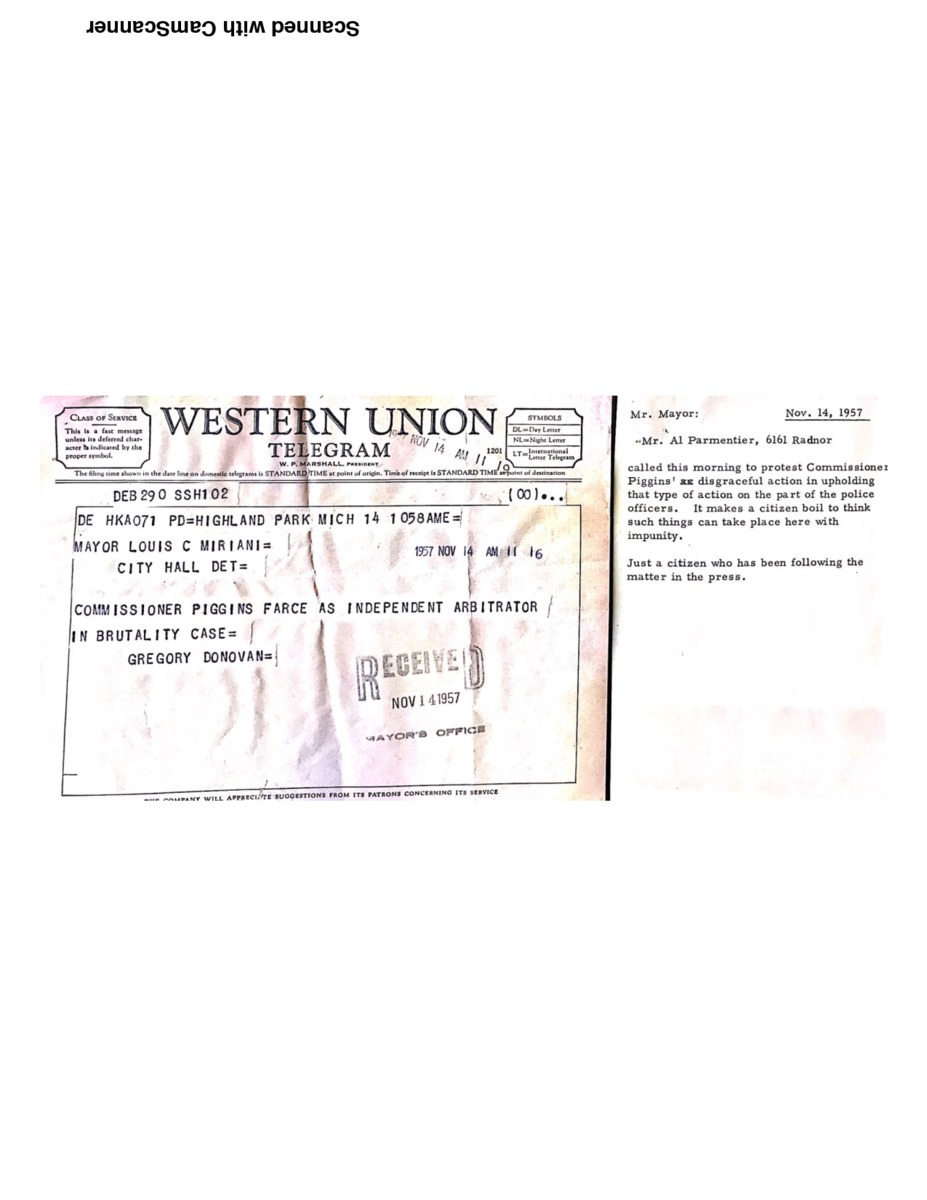

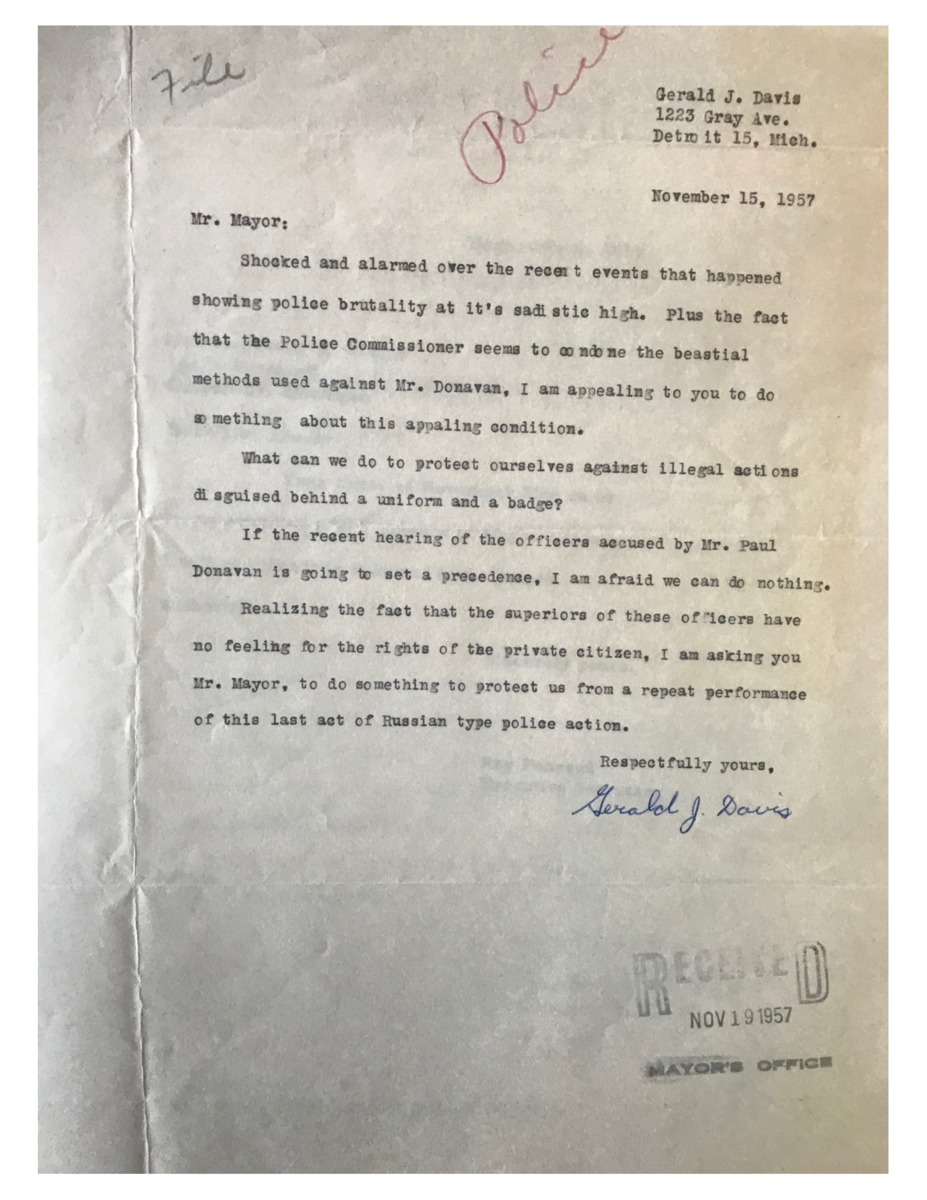

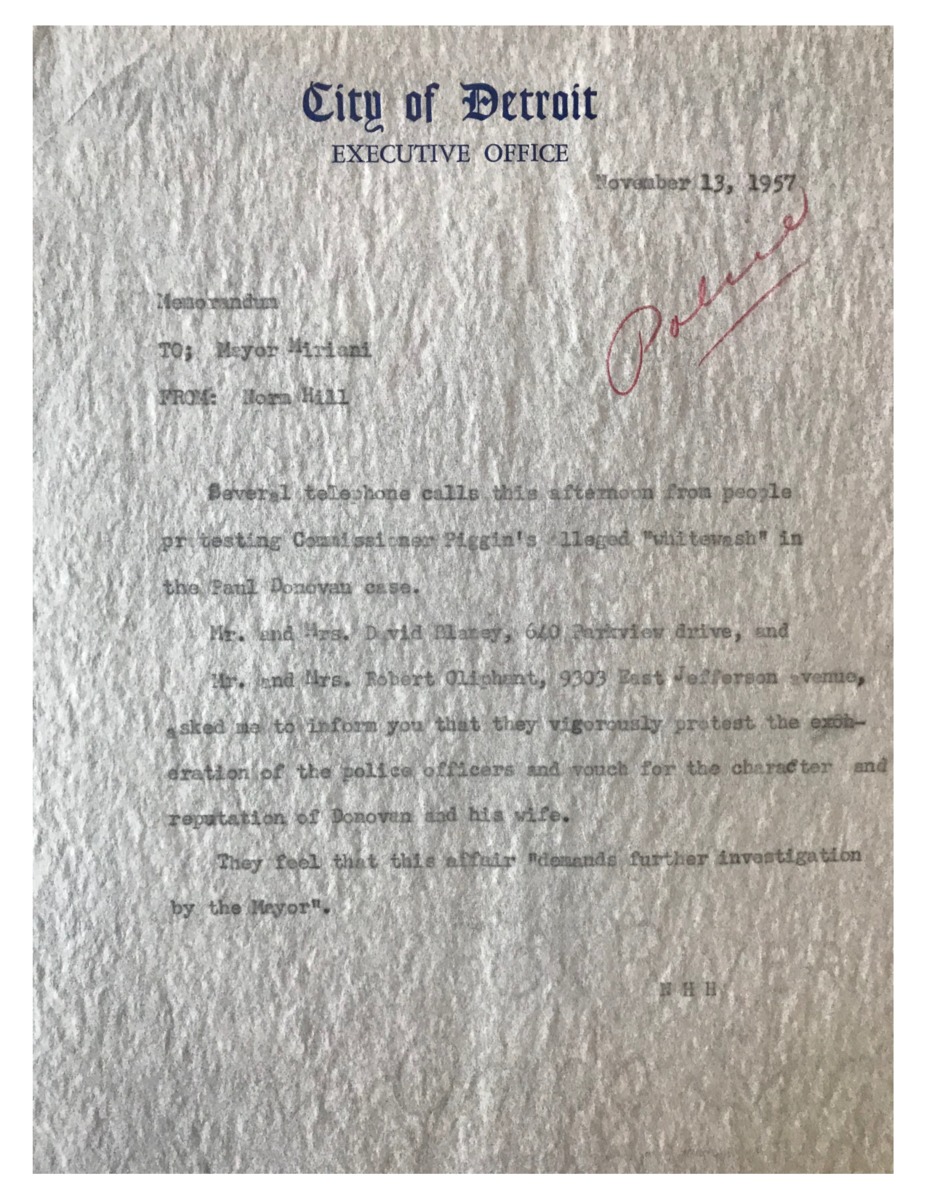

The exoneration of the police officers in the Donovan case caused an outcry from white residents of Detroit. Angry citizens sent letters, telegrams, and phone calls to the police department and mayor's office demanding action against police brutality and calling the investigation a "whitewash" (above gallery).

The Paul Donovan case illustrates that the police brutalized many different types of people, but it is important to emphasize that police brutality against white citizens in the 1950s was not a systemic problem as with African Americans. This case raises additional questions about how the police treated working-class white residents of Detroit, and perhaps even more, how police often responded with violence when anyone questioned their authority, as Donovan did when he asked to be interrogated inside the bar. This was also a major conclusion of the two NAACP reports recounted above: that DPD officers became particularly violent when citizens questioned their authority to conduct interrogations and searches, even with no reasonable suspicion or probable cause.

Sources:

The Crisis (Oct. 1958)

Mayor’s Papers 1957, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Hearings before the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Detroit, Michigan, December 14-15, 1960, Folder 001481-025-0244, Papers of the NAACP, Major Campaigns-Legal Department Files, National Archives

Civil Rights Movement and the Federal Government: Records of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Police-Community Relations in Urban Areas, 1954-1966, ProQuest History Vault

Detroit Free Press, November 7, 1957

Eric C. Schneider, “Dirty Work: Police and Community Relations and the Limits of Liberalism in Postwar Philadelphia,” Journal of Urban History (May 2017), 1-14.

Alex Elkins, “Liberals and ‘Get-Tough Policing’ in Postwar Detroit,” pp. 106-116, in Joel Stone, ed., Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies (2017)