Black Panther Party in Detroit

The Black Panther Party (BPP) formed in Oakland, California, in 1966 and soon spread to a number of cities across the United States. The Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party was always small and not very influential, in a city that already was home to a large number of thriving black power and black nationalist organizations. To the Detroit Police Department, this did not matter.

During 1969-1970, the DPD launched a full-scale repression campaign against the BPP's Detroit chapter, criminalizing its constitutionally protected activities, beating and arresting its members on the street, and deliberately escalating violence. Black and white civil rights activists created the Michigan Committee Against Repression to defend the Black Panther Party, while the police department and city government denied any impropriety. The DPD's harassment campaign culminated in an armed siege at a BPP community center in October 1970 that resulted in the death of one police officer and the mass arrest and prosecution of 15 Black Panthers in their late teens and early twenties for murder. The Michigan Committee Against Repression and other civil rights groups rallied to the cause of the "Detroit 15," arguing that what happened was part of an unconstitutional campaign by local and federal law enforcement to eradicate the Black Panther Party, and the jury acquitted them of murder charges.

BPP Origins and Law Enforcement Response

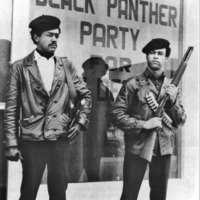

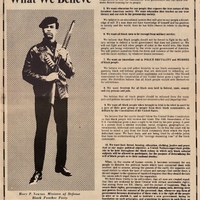

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, in 1966. The two young African American men originally sought to protect the black community from constant police harassment and brutality. In October, the BPP in Oakland released its manifesto, a 10-point program that demanded black political self-determination, full employment, government reparations, decent housing and education, exemption from military service for black men, an end to police brutality, freedom of all black prisoners, and trial for black people by black juries (right). The police brutality plank stated that "all black people should arm themselves for self-defense."

The Black Panther Party of Oakland did not advocate violence, despite what the FBI and police departments around the nation said. The BPP advocated community empowerment and self-defense against illegal police bruality based on the constitutional right to bear arms and the legal right to self defense. The Black Panther Party focused on community-oriented programs, such as free breakfasts for low-income youth, and espoused a radical economic vision to address unemployment, poverty, and racism. But the BPP's militarized style, open display of guns, and community patrols to monitor the police captured by far the most public attention. And the BPP's willingness to fight back and even fire back, if wrongly harassed and fired upon by the police, presented a black power challenge that local and federal law enforcement could not accept. In October 1967, Huey Newton ended up incarcerated after two white policemen pulled him over on yet another trumped-up traffic violation, and in the murky events that followed one of the officers ended up dead. Locally and nationally, the law enforcement escalation of violence after this event was dramatic.

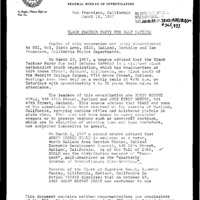

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had named "Black Nationalist-Hate Groups" as a dangerous and violent threat to the nation's internal security two months earlier, in August 1967. The FBI's top-secret, illegal COINTELPRO program worked closely with local law enforcement to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations." The FBI had issued its first COINTELPRO alert about the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense even earlier, in March 1967, warning that Huey Newton and Bobby Seale advocated violence against the police and were recruiting youth into their organization (left). The FBI's claim that the BPP was planning and orchestrating violent attacks on law enforcement served as the rationale/pretext for local police departments in every city with an active BPP chapter to target the group with violence. (Even today, the FBI Vault, its historical archive, falsely asserts that the BPP "advocated the use of violence and guerilla tactics to overthrow the U.S. government").

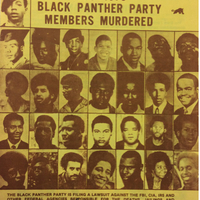

The political violence unleashed in the FBI and police repression campaign against the Black Panther Party was extraordinary. The most infamous is the Chicago Police Department's assassination of the local BPP leader Fred Hampton in December 1969. The Chicago police worked with an undercover informant, part of the FBI's systematic surveillance and infiltration of black power organizations, and murdered Hampton and BPP member Mark Clark while they were asleep. The city of Chicago later paid a $1.8 million wrongful death settlement. Around the country, at least 29 members of the Black Panther Party died in confrontations with, or ambushes by, law enforcement in the decade after 1966.

Criminalizing the Black Panthers in Detroit

The Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party formed in late 1968 and had a few dozen active members. The Detroit BPP organized under the auspices of the National Committee to Combat Facism and based its headquarters in a house on the West Side of Detroit, not far from where the 1967 Uprising began. The members of the Detroit BPP started a free breakfast program for children and often sold copies of the Black Panther newspaper in the downtown commercial district. The BPP did not have a very high-profile presence in the city, where several dozen larger and more established civil rights and black power groups already existed when they emerged.

The Detroit Police Department treated the small BPP chapter as a dangerous enemy deserving of constant harassment, surveillance, criminalization through fabricated charges, politically motivated brutality, and threats to be murdered by police. The DPD's Intelligence Bureau spied constantly on the BPP members, and the FBI's COINTELPRO operation contributed additional "counter-intelligence" information (likely from one or more undercover infiltrators) as well as hyping the propensity for violence by the community control organization. On numerous occasions, groups of DPD officers surrounded the BPP headquarters with weapons drawn, stopped BPP members at gunpoint on the streets, and directly threatened to kill them (threatening to murder someone is a felony crime in Michigan). The DPD also systematically targeted Black Panthers who were in public spaces selling their newspaper, arresting them for interfering with pedestrian traffic, resisting arrest, interfering with an officer, disorderly conduct, and other discretionary charges. On multiple occasions, after these arrests, police officers beat and pistol-whipped the Black Panthers inside the precinct lockup or county jail. Several times the DPD also detained BPP members who were making deliveries for the free breakfast program and destroyed the food.

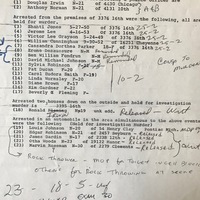

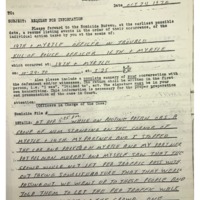

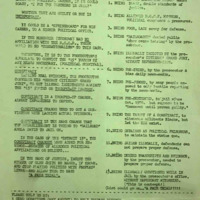

These are just a few of the incidents of police brutality and harassment against the Black Panthers in Detroit during a five-month period between late 1969 and spring 1970 alone, taken from a compilation of 24 formal complaints, many involving teenagers (right):

- 12-11-69: surrounded the BPP headquarters with six squad cars of armed police on a false report of a stabbing there

- 1-30-70: arrested a BPP member who was watching a basketball game on a fabricated charge of assaulting an officer

- 2-23-70: wrongfully arrested a BPP member, removed badges, and beat him at the county jail

- 2-70: arrested a BPP member taking out the garbage, threatened to kill him, and said, "we are waiting for you, Panther, to start something so that we can finish all you n------ off"

- 3-3-70: arrested and illegally detained a BPP member walking from his home to his vehicle; eight officers surrounded him with guns drawn and threatened to kill him

- 4-15-70: arrested a BPP member driving the free breakfast food truck, held him overnight, and destroyed the food

- 4-19-70: arrested a BPP member for stealing his own vehicle

- 5-9-70: arrested two BPP members who were selling newspapers and said, "we killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark and we'll get you next"

- 5-16-70: kidnapped (without arresting) four teenage BPP members around midnight, drove them to an all-white suburb, beat them, and said, "we are going to kill all you Panthers"

Many of the acts detailed here are not just examples of criminalization but are in fact felony crimes committed by DPD officers. It seems clear that the DPD--at the policy level, and not just through individual rogue officers--was deliberately seeking to provoke the Black Panther Party of Detroit to draw a weapon on an officer or commit a retaliatory act of violence in order to justify a massive armed police assault with bullets and not just their fists and nightsticks.

Interactive map of Black Panther Party charges against DPD, fall 1969-spring 1970, in Detroit's racial geography (1970 census)

Note: Zoom the map to view the concentration of incidents downtown, where the Black Panthers sold newspapers, and around their West Side headquarters. Black = police brutality, red = police misconduct, yellow = police intimidation.

Michigan Committee Against Repression

A biracial coalition called the Michigan Committee Against Repression (MCAR) presented the list of 24 incidents of DPD brutality and harassment against the Black Panthers to Mayor Roman Gribbs and Police Commissioner Patrick Murphy in May 1970. MCAR was an ad-hoc group created for this purpose and included Detroit's two most influential African American politicians, congressman John Conyers and state senator Coleman Young, as well as leaders from the NAACP, United Auto Workers, Catholic diocese, and others (below left).

The coalition demanded an investigation into the DPD's repressive measures and warned that unless the city restrained the police department, the situation could soon spiral out of control. At the meeting with the mayor and police chief, the Michigan Committee Against Repression made three additional demands:

- Force the police department to stop harassing people selling Black Panther newspapers

- Discontinue the infiltration of the BPP and other activist groups by youthful police spies

- Made public the secret files of the DPD's Intelligence Bureau, which surveilled political groups and activists

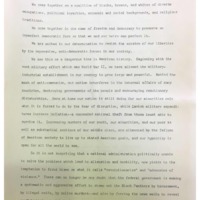

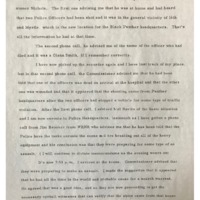

The dramatic response of the Michigan Committee Against Repression, which was not a black militant organization and which contained a number of mainstream civil rights and white religious leaders, showed how polarized the political climate in Detroit had become by the spring of 1970. MCAR simultaneously released a manifesto (below, second from left) stating that, as a multiracial and interfaith coalition:

The Detroit Police Department investigated itself and found all of its interactions with the Black Panther Party to be "routine and proper." The investigation reviewed police records, rather than interviewing civilian witnesses, and of course took the police descriptions of the encounters as factual. Police officers stated that they arrested Black Panthers who were selling newspapers because they yelled "Kill the pigs," threatened to "shoot" the police, physically assaulted law enforcement officers, and intimidated civilians. When a police record of the encounter did not exist, the DPD investigation presumed that the Black Panthers had made up the incident, when the far more likely scenario is that police officers who illegally arrested, detained, and beat civilians did not create an official record about it.

In July, Mayor Gribbs informed the Michigan Committee Against Repression that the matter was closed because the DPD had not committed any acts of brutality or misconduct. Instead the city government placed all blame on "illegal and questionable activities" by the Black Panthers. The Gribbs administration also explained that the confidential activities of police informants and the DPD's Intelligence Bureau were valuable methods of peace-keeping and crime control and could not be opened to the public.

Review documents from the Michigan Coalition Against Repression and the city government's denial of misconduct against the Black Panthers in the gallery below.

Oct. 24, 1970: The Police-Panthers Shootout and Siege

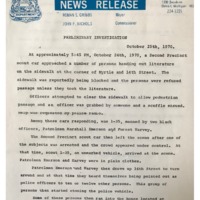

On October 24, 1970, the Detroit Police Department instigated the violent encounter with the Black Panther Party that its officers had been seeking for months. The shootout at the BPP's community center on the near West Side began with a typical incident of police harassment of young activists distributing newspapers on the sidewalk.

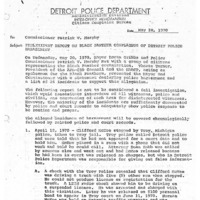

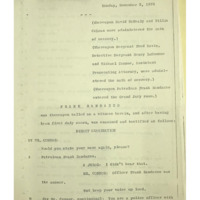

According to the police report and later trial testimony, Patrolman Randazzo and Patrolman Murphy observed a group of N/M (Negro males) obstructing the flow of pedestrian traffic while passing out literature around 5:45 p.m. on the corner of 14th and Myrtle (now Martin Luther King Blvd.), two blocks from BPP headquarters. The officers told the group to disperse and one African American male said, "I'm not going anywhere." (In the initial police report, Randazzo wrote that this unidentified male said, "It's all over now," but he did not testify to these words at the grand jury). Patrolman Randazzo then sought to arrest this person, who allegedly tried to punch the officer. The squad team called for backup, "put two thugs in the scout car," and drove to the precinct station.

The police version (and grand jury prosecutor) ommitted a crucial detail, that Patrolman Randazzo beat the 21-year-old BPP youth on the sidewalk with his blackjack in front of the crowd. Multiple civilian witnesses recounted that a casual episode of police brutality was what escalated the situation, combined with a police response of overwhelming force.

Within ten minutes, multiple police cars had arrived on the scene at 14th and Myrtle, including two African American undercover officers, and Patrolman Randazzo had returned after dropping off his prisoners. The officers were highly armed, as seen in the photograph at right. Someone in the crowd, presumably one of the BPP members, informed everyone present that the two young black men in plainclothes were actually police officers. According to the police report, people in the crowd began throwing rocks at the police cars.

The police chased several black youth into a vacant house two blocks away, on the corner of Myrtle adjacent to 3376 16th Street, the BPP community center . Several police officers fired shots at the fleeing youth and into the vacant house (the police reports obscured these details and made it seem like all police gunfire came after the BPP house fired on the police, which seems contradicted by witness accounts and the police trial testimony). According to police accounts, someone from inside the vacant house, or from somewhere, fired a shot and wounded Patrolman Marshall Emerson, one of the undercover black officers, in the hand.

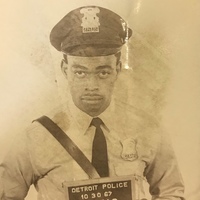

It is not clear who fired first at 3376 16th, which happened in the same time sequence as the police gunfire into the vacant house next door. A large group of heavily armed police officers surrounded the BPP community center, taking up attacking positions and using their squad cars as shields. Then a gunshot, allegedly from inside the community center, struck and killed Patrolman Glenn Smith, a uniformed African American officer who had arrived as backup. Randazzo testified that he saw "a long barrel come out of the window" of the house at 3376 16th around 6:05 p.m. and fire a single shot that killed Smith, who was in front of the vacant house.

The DPD then proceeded to place the BPP community center at 3376 16th under a protracted siege that lasted for nine hours. There were fifteen people inside, eight male and seven female, all in their late teens or early twenties. Commissioner John Nichols wanted to storm the building in a full-scale assault, but Mayor Gribbs urged patience and in doing so, likely saved a number of lives that night. At his request, the DPD gave orders to officers on the scene to hold their fire. This allowed the city of Detroit to negotiate a partial truce through a delegation of civil rights leaders, city officials, and BPP attorneys.

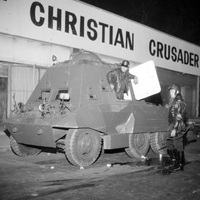

Around 2:30 a.m., twelve of the occupants surrendered to this delegation, which guaranteed their safety. Three BPP members remained in the community center, refusing to surrender. The DPD brought in an armored vehicle and fired tear gas into the building, and then one or more occupants inside fired gunshots out the windows. A DPD sharpshooter fired back. Around 2:45 a.m., the remaining BPP members surrendered, denouncing "pigs" and "facism" as they were arrested. In a press release, the DPD announced that that "several high powered rifles" were recovered from the building.

The DPD arrested all 15 of the occupants of the BPP community center at 3376 16th for the murder of Patrolman Glenn Smith. All told, the DPD arrested 23 Black Panthers on Oct. 24-25, including the two 21-year-old men detained in the initial sidewalk encounter and six other young men held as part of the murder investigation. During the siege, unknown persons firebombed and destroyed four police cars.

Read the DPD's and mayor's versions of these events in the gallery below.

The "Detroit 15"

The Detroit Police Department held a massive funeral for Patrolman Glenn Smith, a Detroit native and military veteran, with hundreds of officers marching in formation. The DPOA union memorialized him as "the latest victim of Black Panther attacks on Police Officers," which it portrayed as a nationwide conspiracy by criminal revolutionaries.

Wayne County prosecutor William Cahalan charged all 15 of the occupants of the BPP community center with premeditated first-degree murder of a police officer, and the grand jury returned a collective conspiracy indictment in early November. The defendants were between the ages of 17 and 22, half male and half female. The prosecutor secured very high bonds, which meant that the Black Panther members were held for months in the awful and brutal conditions of the Wayne County Jail, which was currently enmeshed in a major class-action lawsuit and would be found unconstitutional in the spring of 1971.

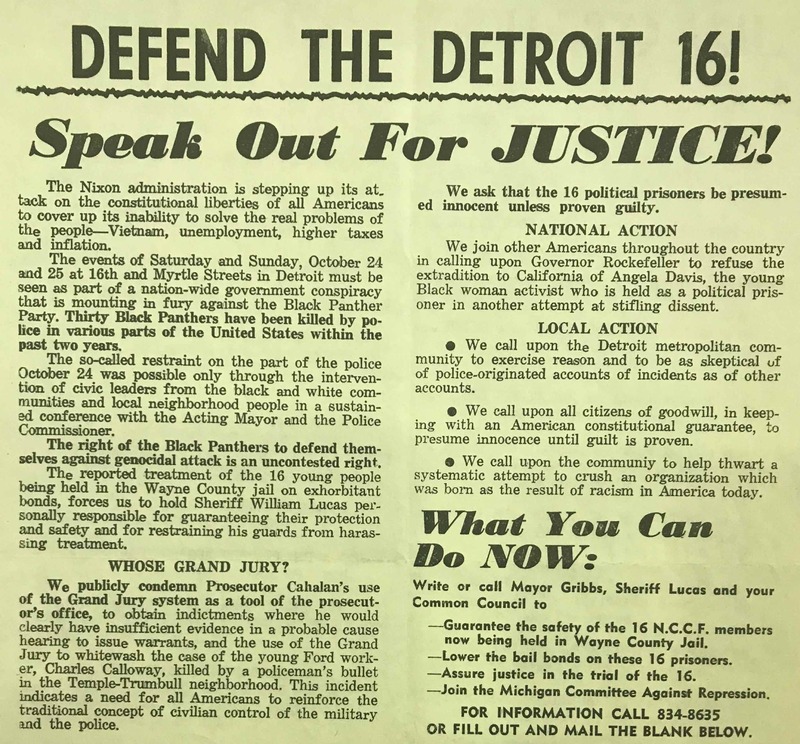

The Michigan Committee Against Repression, led by Rep. John Conyers and State Sen. Coleman Young, held a mass protest meeting on November 14 and portrayed the police attack and prosecutorial indictment of the Black Panther Party as part of a "nation-wide government conspiracy that is mounting in fury." MCAR argued that the BPP members were "political prisoners" who had the right to "defend themselves against genocidal attack" and blamed a broad spectrum from local officials to the Nixon administration for the conditions of violence.

The Black Panther Party contended that the city and county government was framing and persecuting the Detroit 15 "for feeding hungry kids in the morning, for trying to establish a free medical clinic, . . . and other survival programs." The BPP called on the black community to mobilize to free these political prisoners, "by any means necessary."

Civil rights and left-affiliated groups, led by the Michigan Committee Against Repression, also established a Committee to Defend the Detroit 15 as the spring 1971 trial date approached. The committee accused Prosecutor Cahalan of manufacturing evidence and destroying the lives of young community activists as part of a racist agenda. The committee also charged that the prosecutor coerced a 17-year-old youth into testifying falsely against the other BPP members who were in the community center (at the trial, this youth refused to testify and was jailed for contempt). In another flyer, the Committee to Defend the Detroit 15 highlighted the parents of several of the defendants, who accused the prosecutor of railroading poor black youth in an act of political retalilation against the Black Panther Party.

At the conclusion of the trial, the jury acquitted all of the BPP defendants on murder charges, in large part because there was no evidence linking any individual defendant to the death of Glenn Smith. The jury did convict three of the BPP defendants, the ones who had initially refused to surrender and allegedly fired on police after the tear gas attack from the armored vehicle, on felony assault charges that carried a four-year prison sentence.

Read documents from the political defense of the Black Panther activists in the gallery below.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Ernest Goodman Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

MaryAnn Mahaffey Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit News Photographic Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Subject Vertical Files, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Fifth Estate Records, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Tuebor: The Official Organ of the Detroit Police Officers Association, Nov. 1970

Detroit Free Press, July 1, 1971

FBI Records: The Vault, https://vault.fbi.gov

Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (2010)