Property Damage

Calculating the Damage

Arson, looting, and other forms of property destruction caused massive damage during the Detroit Uprising of 1967--in addition to the incalculable loss of life chronicled in the following section. Around 1,600 separate structures suffered damage of some kind, including businesses that were looted and burned, and residential dwellings that also caught fire as the flames spread into adjacent neighborhoods. Investigations and relief efforts estimated the total cost of the property damage to be $132 million (around $1 billion in today's dollars).

During these six days in July 1967, at least 552 buildings burned. The most common structures damaged by fire were:

- Single-family and dual-family residences (102)

- Grocery stores (57)

- Residential and commercial mixed-use buildings (44)

- Apartment houses (37)

- Furniture stores (24)

- Cleaners (20)

- Drug stores (19)

- Clothing stores (18)

There is considerable evidence that some participants in the civil unrest targeted businesses and apartment buildings owned by outsiders, in particular white property owners who lived in the suburbs and took advantage of the captive market that racial segregation in housing created. In 1965, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission had warned that the situation in some of Detroit's poor black neighborhoods was explosive, citing not only police brutality but also the frustrations of African Americans living "in abject poverty, exploited by merchants and property owners."

Overall, at least 538 buildings were completely destroyed and another 549 suffered significant damage. Small business owners were hit particularly hard. It is important to note, however, that many of the buildings burned or destroyed were the apartments, single-family homes and duplexes, and businesses that African Americans owned and/or lived in. Assessing damage to property, in preparation for the relief and rebuilding efforts, therefore had political and racial overtones. Insurance companies and government agencies provided compensation to property owners, not to renters, which particularly affected the displaced African American residents who did not own their own homes.

On July 29, President Lyndon Johnson officially declared the "riot-torn sections" of the city Detroit to be "disaster areas" (below right), making affected business owners and homeowers eligible for low-interest rebuilding loans from the federal government. This policy also excluded renters from receiving any direct assistance.

There is no question that the local, state, and federal governments spent more time and energy investigating and assessing the damage to property than they did investigating and assessing the loss of life and the many allegations of police brutality and misconduct. This is not at all surpising, since law enforcement and the Michigan National Guard mobilized in July 1967 with explicit orders to use deadly force if necessary to defend private property. The Visualizing Detroit '67 and Scenes of Devastation pages later in this section critically analyze the state of Michigan's extensive effort to document the damage done to property compared to its inadequate concern for excessive force, criminal actions, and loss of life caused by state agencies.

A Broad Spectrum of Victims

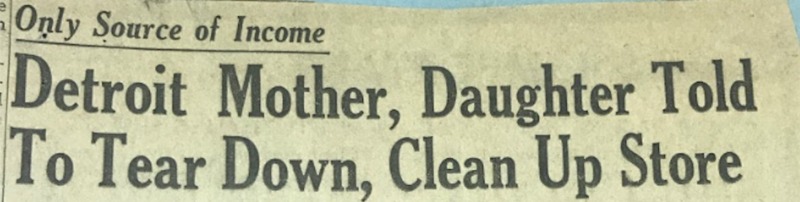

Many small business owners did suffer significant personal as well as financial losses in the Uprising. Mary Trabulsy, for example, was a Lebanese immigrant and a 65-year-old widow with a polio-ridden daughter. She rented out her property to a grocery store, a dry cleaner, and two residential flats. She subsisted on her monthly social security checks and the rental income. The violence downtown left her store completely destroyed, and much of her income disappeared. Then, in mid-August, the city of Detroit sent her an order to tear down the remains of the condemned building, at a cost to her of $1,800. Like many small business owners, Mrs. Trabulsy did not have insurance to pay for such an event. She struggled to provide for her family in the aftermath, and is one of the tens of thousands of people whose lives were disrupted by the civil unrest of July 1967.

Some of the areas most damaged by arson were along 12th Street, Linwood, and Grand River, in neighborhoods inhabited almost exclusively by African Americans. (Visit this page for photographs of the extensive damage on these streets). Arsonists would fill up cans of gasoline and set buildings aflame, and some battled firefighters who responded to the blazes. Because of the considerable winds that occurred during the week of the Uprising, fires spread across the city with extreme ease and speed.

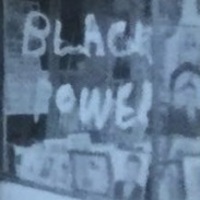

Looters also broke windows and stole merchandise from a number of businesses, especially during the first few days from July 23-25. A majority of the looters were African American, although a number of white residents of Detroit also participated. While some crowds targeted white-owned establishments, African American business owners also suffered significant losses. Many store owners wrote signs in the windows to try to discourage looters from targeting their businesses, such as this "Black Power" slogan (left) painted on the front window, another indication of the clearly political nature of the Uprising. One African American owner whose store was devastated told the media that he would not be able to recover, "because we can't get insurance in this area," due to the racial discrimination and redlining of banks and financial institutions.

The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's African American weekly newspaper, also reported on the complaints of black business owners that the police did nothing to protect their properties from looters and arsonists. The Chronicle asked, of the epicenter of the July 23 events, "Did the police just write off 12th?" One longtime resident complained that the police were "just standing around" and not even trying to protect the business owners and homeowners in the community. This criticism is, of course, part of a complicated debate, since the Detroit Police Department defended itself from critics who argued that it should have moved in immediately on the morning of July 23 with overwhelming force, and from critics on the other side who charged the DPD with excessive and deadly force.

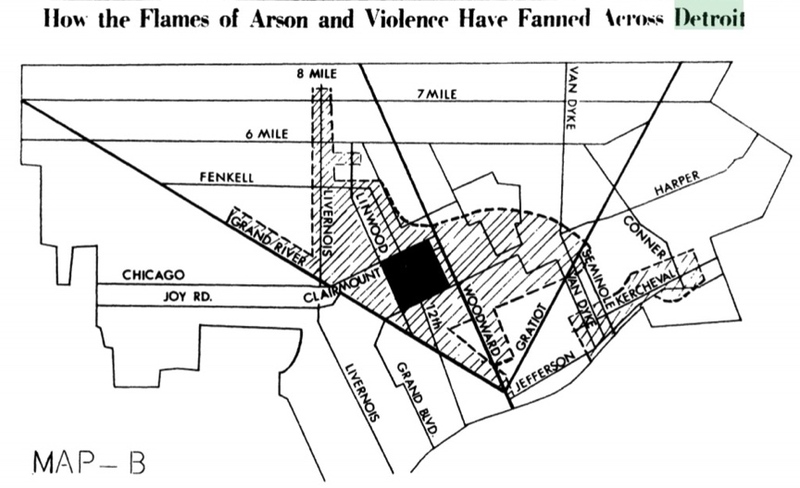

Below left, find news footage of an African American woman whose house burned down on Linwood Avenue near the 12th Street epicenter. Below right, a map of the spread of the arson zone from the investigative files of the Kerner Commission.

Sources:

Property Damage During Riots, August 1967-February 1968. Civil Rights during the Johnson Administration, 1963-1969, Part V: Records of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission). Series 20. Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

"Riots and Protests. Detroit 1967," General Photographic Collection, Michigan State Archives, Lansing, Michigan

Only Source of Income: Detroit Mother, Daughter Told to Tear Down, Clean Up Store. Box 396, Folder 5. Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

"Did Police Just Write Off 12th?" The Michigan Chronicle, July 29, 1967

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University