V. STRESS and Radical Response, 1971-1973

The Detroit Police Department killed at least 108 people between 1971 and 1973, a higher number of civilians per capita than any other city in the nation. Almost all were young African American males, and the majority were unarmed. The average annual total of police-involved fatalities during this violent three-year period exceeded the 28 civilians killed by DPD officers during 1943, the year of the city's worst race riot, and the 25 civilians known to have been killed by the DPD during the year of the 1967 Uprising. At the peak, the 43 people officially acknowledged to have been killed by DPD officers in 1971 equaled the total number of deaths caused by all law enforcement agencies during the week-long Uprising of July 1967 and was surpassed in the city's history only by the extreme police violence and corruption enabled by the Prohibition of alcohol during the mid-to-late 1920s. Non-fatal shootings of civilians by police also escalated during the early 1970s, when gunfire by DPD officers wounded an estimated 250-300 people, and quite probably more. As with all data on police use of deadly force, the official totals are unreliable and almost certainly represent undercounts, because of deliberate archival silences that disguise the full scope of state violence by law enforcement.

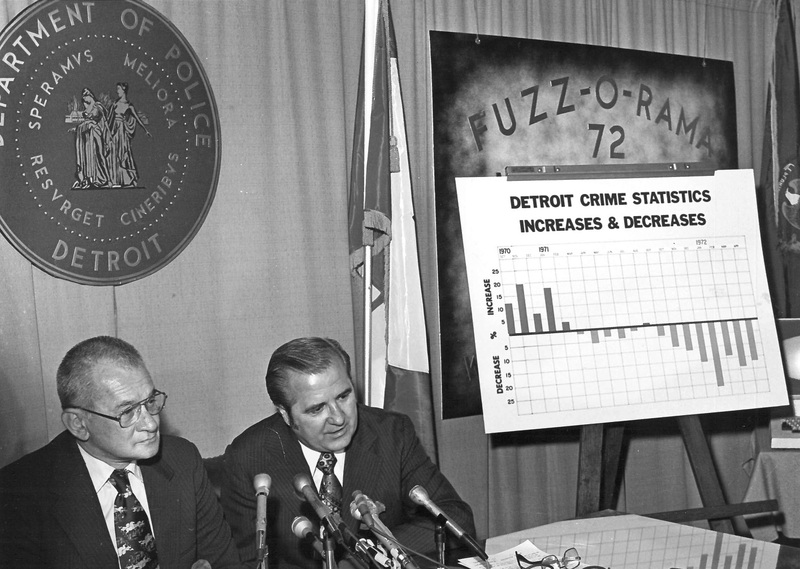

The STRESS unit of the Detroit Police Department alone killed at least 22 people, and shot and wounded dozens more, between its creation in early 1971 and its abolition at the end of 1973. STRESS, an acronym for "Stop the Robberies--Enjoy Safe Streets," represented a militarized philosophy of "proactive policing," with undercover officers deployed to alleged crime hot spots disguised as potential victims in order to "interdict" and attack muggers and robbers before they could act. The political champions of STRESS included Mayor Roman Gribbs, a racial conservative and former Wayne County sheriff elected in 1969 on a punitive law-and-order platform supported mainly by Detroit's white neighborhoods, and Police Commissioner John Nichols, a longtime DPD veteran and hardline crime warrior appointed by Gribbs in 1970. They portrayed the undercover decoy operation as a dramatic success that had greatly reduced street crime, especially robberies and muggings, and made the city safe again. Nichols, who consistently denied that police brutality existed and adamantly opposed any civilian oversight of the police department, contended that STRESS had deterred "the violence of the mugger, the strong-arm artist, the armed bandit." Detroit's white leaders and the DPD hierarchy also repeatedly insisted that, because of its effectiveness, STRESS enjoyed the support of a majority of Detroit's Black residents. Gribbs and Nichols rarely said explicitly what was completely clear to everyone: STRESS violently and almost exclusively targeted the young African American males widely perceived as the cause of the city of Detroit's crime problem. Also, while the DPD publicly justified STRESS as an effort to protect Black crime victims in dangerous neighborhoods, the unit primarily deployed in the racially mixed commercial districts in the downtown and midtown areas. Its unstated but central rationale was therefore to escalate the criminalization of Black youth in these public spaces, protect the financial investments of white-owned businesses, and send a message to the white residents of the metropolitan region that law enforcement would esure their safety through violence during a time of rapid white flight to the suburbs and widespread racial fears that the looming Black majority in Detroit's politics would mean the downfall of the central city.

The racial violence caused by STRESS, and especially the unit's growing death count, led to the most broad-based anti-police brutality movement in the city's history and contributed directly to the election of Coleman Young, Detroit's first Black mayor, in the fall of 1973. A coalition of Black radical groups played the leading roles in the anti-STRESS campaign, which emerged in force after a white STRESS officer fatally shot two unarmed African American teenagers in the fall of 1971 and reached its climax after the DPD systematically violated the rights of Black citizens during a manhunt for three Black community activists following their armed confrontation with STRESS officers in December 1972.

The movement to abolish STRESS ultimately included mainstream civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, the Black police officer association Guardians of Michigan, and African American elected officials including U.S. Rep. John Conyers and state senator Coleman Young. In the 1973 mayoral election, Young promised to eliminate the unit as part of a broader transformation of the police department, and his main opponent was none other than DPD Commissioner and STRESS champion John Nichols. The coalition of black power, civil rights, and other radical leftist groups denounced STRESS as an illegal entrapment operation, accused the DPD of manipulating crime data to deceive the public about its success, and labeled the unit a "murder squad" designed to terrorize and control the Black community. While activists won civil litigation settlements for some of the STRESS victims, no police officer was ever convicted in criminal court for any STRESS-related crimes.

War on Crime and Drugs < > War on Black Detroit

STRESS dominated the political debate about the Detroit Police Department in the early 1970s, and its history is the main focus of this section of the Detroit Under Fire exhibit, but the controversial surveillance and decoy unit also represented only the most prominent aspect of the DPD's "proactive policing" philosophy and racially targeted crackdowns during this era. Basic police procedure continued to revolve around the discretionary criminalization of African American neighborhoods, especially poor and working-class areas, in addition to flooding the downtown and near-downtown commercial districts to maintain 'order' in the spaces where Black and white residents of the city and its segregated suburbs were most likely to encounter one another. At a time of continued white flight from Detroit's residential neighborhoods (see map below), STRESS and other police units therefore operated to criminalize Black youth and protect white capital in public spaces associated with corporate investment, shopping and entertainment, sports and tourism, and gentrification. DPD officers continued to systematically target Black pedestrians and motorists through stop-and-frisk policies that had been codified by a 1968 city ordinance and subsequently legitimated by the federal courts. The DPD also continued to reject and dismiss citizen allegations of police brutality and, along with the Detroit Police Officers Association union, to obstruct and whitewash investigations into officer misconduct. And the DPD's so-called Criminal Intelligence Bureau continued its campaign of illegal political surveillance and infiltration of black power and other leftist organizations, in alliance with the parallel efforts of the Michigan State Police and the broader COINTELPRO program of the FBI.

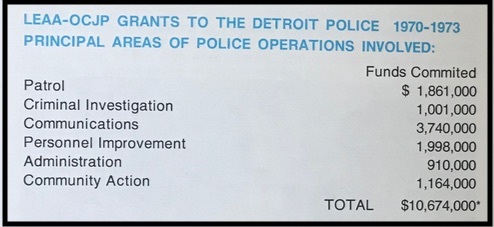

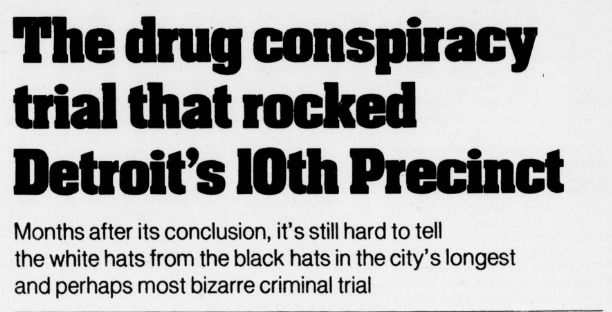

The expansion of militarized, racially targeted law enforcement in Detroit during the early 1970s took shape in the context of the punitive federal wars on crime and drugs during the Nixon administration. After Nixon's election, the federal government intensified the racialized war on street crime that the Johnson administration had declared in 1965, and that Congress had enhanced with the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. Federal crime control programs provided more than $10 million in grants to the Detroit Police Department during the early 1970s, most allocated for street-level enforcement (right). At the same time, the Republican administration slashed funding for the social welfare and antipoverty programs that liberals had viewed as the supplement to the get-tough crackdown by police. In 1971, President Nixon further declared an "all-out offensive" against illegal drugs, which he labeled "America's public enemy number one." Nixon and the U.S. Congress enacted lengthy mandatory-minimum sentences for "drug pushers and peddlers," based on selective enforcement that criminalized poor urban communities of color, and state governments ratified their own harsh measures as well. Federal and state funding for drug enforcement flowed into American cities, leading to an escalation of anti-narcotics policing but also creating extensive opportunities for official corruption. In Detroit, as in a number of other major urban centers, the early 1970s brought major scandals as police officers took payoffs from heroin traffickers and allowed illegal drug markets to flourish, contributing directly to the increase in crime and violence in Black neighborhoods.

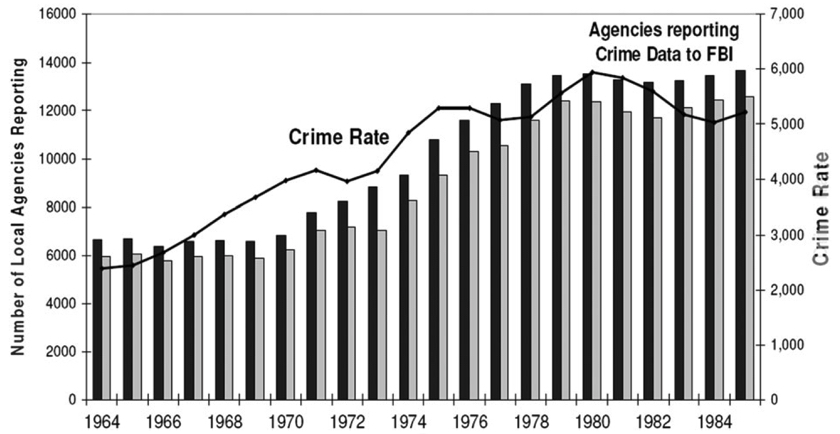

The government wars on crime and drugs escalated racial tensions and police violence in urban areas across the United States. Federal crime and drug control programs ramped up the militarization of local police departments and funded "the virtually indiscriminate use of decoy and plainclothes operations in targeted urban areas," as scholar Elizabeth Hinton observed in her study of STRESS in Detroit and the broader nationwide impact of the war on crime. "Excessive punitive force in segregated urban communities often precipitated violence," according to Hinton, and "only intensified the problems of crime and poverty that national officials aimed to prevent." Scholars also have emphasized that the dire warnings of a dramatic crime wave in the late 1960s and early 1970s were exaggerated and based on "flawed statistical data [that] overstated the problem of crime in African American communities," especially because police departments and the federal government utilized arrest statistics--which reflected selective policing and discretionary enforcement--rather than convictions as the measure of "crime" (see chart bottom of page). Violent and property crime was a real social problem in struggling urban neighborhoods, exacerbated by poverty and unemployment, and the discriminatory under-policing of these communities often accompanied the over-policing patterns of selective enforcement and brutality by law enforcement. But militarized crackdowns such as the STRESS operation did not make Detroit safer; instead, "proactive policing" escalated racial violence and excessive force while facilitating criminality and corruption by law enforcement officers on a broad scale.

In the mid-to-late 1960s, liberal reformers in Detroit had emphasized "community policing" and enhanced "police-community relations" through a tough-on-crime agenda that also promised to diversify the DPD and provide fair and color-blind law enforcement by focusing on actual criminals and not brutalizing law-abiding Black citizens. The liberal reform era never lived up to its promises of "law and justice," not least because community policing was always more of a public relations strategy than an actual shift in policing practices. Under the Cavanagh administration, the discretionary criminalization of poor Black neighborhoods always shaped crime control philosophy and strategies, as did the deployment of the Tactical Mobile Unit and other militarized forces to maintain order and criminalize Black citizens in the downtown business district and other commercial areas. White liberal politicians also consistently defended the DPD's use of force against civilians and refused to support substantive measures that would actually deter and discipline the rampant problem of illegal police brutality and misconduct. Even so, liberal reformers lost control as the overwhelmingly white DPD increasingly operated as an autonomous right-wing political institution during the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the political and racial violence that police officers instigated was extensive, deliberate, and often shocking.

But then, in the STRESS era of the early 1970s, the racialized violence and preemptive use of deadly force committed by the Detroit Police Department became even worse, even more widespread, and even more clearly sanctioned as official policy. The liberal mayoral administration of Jerome Cavanagh, in power from 1962-1969, depended on the support of Black voters and therefore, even as it intensified the crime war in African American neighborhoods, still had to govern through negotiations with mainstream Black leaders and civil rights organizations. The conservative Gribbs administration took charge in 1970 on the strength of a racial backlash based in Detroit's working-class white neighborhoods, which were actively resisting integration in housing and public schools and demanding an even more aggressive police crackdown on the Black community. Their political control was short-lived, because Detroit's white population declined from 56% to 34% during the 1970s (see map below), but this also meant that the final stage of white dominance in a city on the verge of a Black majority brought incredible violence, with the overwhelmingly white police department as the main instrument. The white men in charge of Detroit's law enforcement operations during the STRESS era included a conservative law-and-order mayor (Roman Gribbs) who had previously been county sheriff, a right-wing police commissioner (John Nichols) who ran to be the mayor's successor through a pro-STRESS campaign designed for the city's segregated white neighborhoods, and a reactionary county prosecutor (William Cahalan) who automatically justified fatal shootings and other forms of police violence no matter what the circumstances. The deadliest era of police violence in Detroit's modern history claimed many victims but also led to a massive grassroots campaign by black power and civil rights organizations that demanded justice and insisted that the African American community that had become a majority of Detroit's population also had to take political control of the city government and reign in the lawless Detroit Police Department.

Map of the Racial Demographics of Detroit, 1970 and 1980

Explore Detroit's transition to a majority-Black city during the 1970s, when the white population declined by more than 425,000 residents and the Black population increased from 44% to 63%. Hover over census tracts to view racial data, and use the zoom function in the bottom corner for a closer look at downtown and other sections of the city. Many of the police shootings between 1971-1973 took place in or near these racially transitional neighborhoods as DPD officers protected white-owned businesses and residences from low-level property crimes with fatal force.

Chart of U.S. Crime Rate Increase Alongside Increase in Local Agencies Reporting Crime Data to the FBI, 1964-1984

Sources:

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

John Wesley Domm, “Police Performance in the Use of Deadly Force: An Analysis and a Program to Change Decision Premises in the Detroit Police Department (Ph.D. diss., Wayne State University, 1981)

Catherine H. Milton, et. al, Police Use of Deadly Force (Police Foundation, 1977), National Criminal Justice Reference Service, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/41735.pdf

Allen Phillips, "STRESS: A Concept as well as a Unit," Detroit News, March 21, 1973

Thomas V. LoCicero, "The Drug Conspiracy that Rocked Detroit's 10th Precinct," Detroit Free Press, September 26, 1976

Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (2017)

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)

Vesla Weaver, “Frontlash: Race and the Development of Punitive Crime Policy,” Studies in American Political Development (Fall 2007)

Richard Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control,” June 17, 1971, American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-drug-abuse-prevention-and-control