3. Political Police Violence

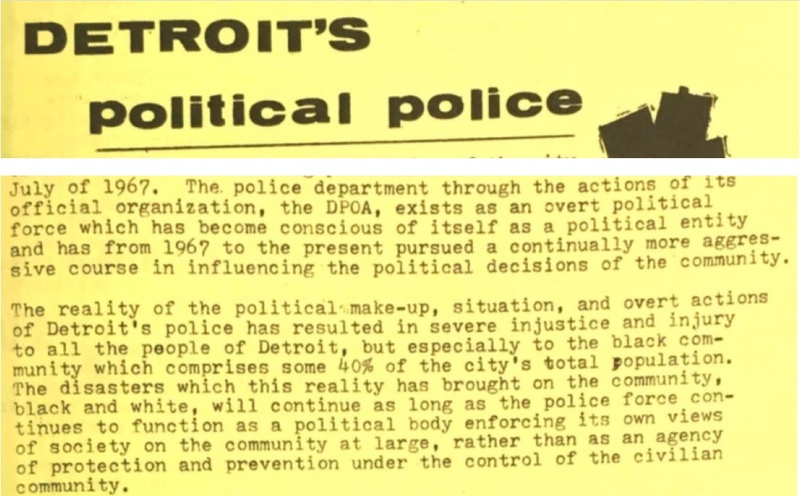

Police departments have always been political actors in urban politics, but the Detroit Police Department and the DPOA police union took on explicitly politicized roles in the city of Detroit in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in direct response to the expanding efforts of black power and community control movements to curb police brutality and enact democratic reforms. The liberal Cavanagh administration had unleashed and militarized the police department in its get-tough crime control campaign, justified the extreme racialized police violence during the 1967 Uprising, and done almost nothing to address the DPD's stonewalling and routine exonerations in almost all internal investigations of police brutality and misconduct. The overwhelmingly white, ideologically conservative police department then pushed the discretionary authority granted by liberal crime control politics to the outer limit, insisting that there should in effect be no democratic checks on its authority to maintain "law and order," a mission that revolved far more around preemptive criminalization than around actual crime control.

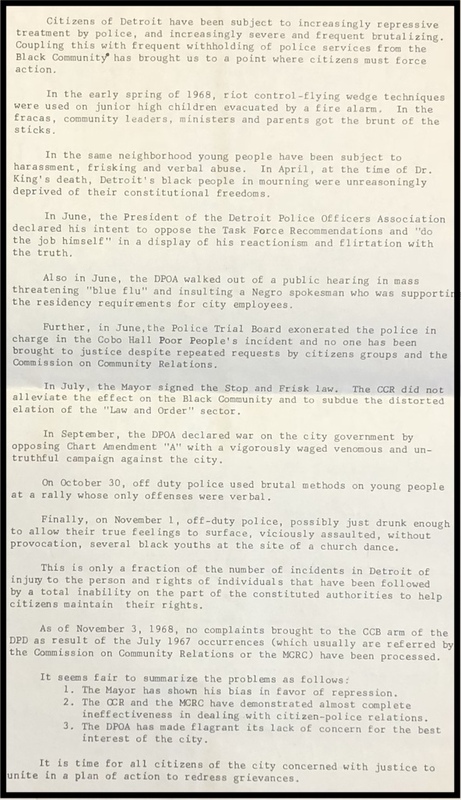

In the late 1960s, anti-police brutality activists accused the DPD and the DPOA union of operating overtly as a right-wing political institution, in an alliance with the segregationist white majority, in order to maintain racial control of the African American community and consolidate power by further inflaming an already racially polarized city. State senator Coleman Young, a longtime DPD critic, enumerated the police department's many abuses of power in 1968 alone in the manifesto at right. Young listed the DPD's violent attacks on black student protesters in public schools, pacifist activists in the Poor People's Campaign, youth protesters at a George Wallace rally, and African American teenagers at a church-sponsored dance, among many other acts of police oppression. The DPD's internal investigation process had demonstrated a "total inability" (or unwillingness) to do anything about these violations of the constitutional rights of citizens, and the power of the DPOA union had made a very bad climate of police repression even worse.

Extreme white conservatives took over the leadership of the Detroit Police Officers Association union in the mid-1960s as part of the broader get-tough on crime politics of that era and the hostile reaction of white police officers to the modest civil rights reforms endorsed by the liberal Cavanagh administration under the guise of "fair and equal" policing. The DPOA had been around since the 1940s but had generally operated more as a professional association than as an independent union and had followed the lead of the DPD hierarchy. That changed starting in the mid-1960s when the DPOA, led by Carl Parsell, began to emerge as an independent political force in city politics and often threatened the DPD and mayoral adminstration with "blue flu" strikes at any hint of oversight of police discretion and investigations into police misconduct and brutality. The DPOA obstructed all investigations of police officers as a matter of course, provided legal representation for officers charged with crimes such as murder and rape, and frequently litigated even mild internal discipline against officers for extreme brutality against black citizens. Coleman Young flatly labeled the DPOA union "racist," and many African American officers were not members, instead choosing to be affiliated with the all-black Guardians police officer association. In the late 1960s, black officers in the Guardians warned that "the DPOA is a danger to Detroit, you better believe it," and stated that "they seem as if they're trying to start a riot."

The DPOA escalated its political activities in 1969, seeking to remove an African American judge after he restrained police misconduct in the New Bethel Incident, threatening a "blue flu" strike if the ballot initiative for a civilian review board succeeded, and endorsing and actively campaigning for the successful law-and-order candidate Roman Gribbs against his African American opponent in the 1969 mayoral election. According to Coleman Young, the DPOA's power had forced black politics to confront "the central issue, . . . just who is running this city--the police or the people."

The Detroit Police Department and the DPOA union considered the discretionary use of force against political activists who were engaged in protests and demonstrations, or just in a group in public space, to be inherently justified, full stop. The DPD's operational policies gave officers the right to order "unruly" and "disruptive" crowds to disperse and, like the discretionary stop-and-frisk law that the city of Detroit enacted in 1968, these assessments were left up to the "professional" judgment of the policemen on the scene. The Tactical Mobile Unit's stated mission included "crowd control" and control of political demonstrations, and neither TMU riot police nor regular DPD officers had to wait for any actual illegality to take place before moving in with force and, often, extreme and indiscriminate violence. DPD officers could and often did justify their actions by accusing and arresting political activists and demonstrators for trespassing, loitering, disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, obstructing an officer, assaulting an officer, and the full range of discretionary polices of criminalization available to control the public.

We think of politically motivated police violence against nonviolent civil rights protesters to be something that happened in the Jim Crow South, circa 1963 in Birmingham or circa 1965 in Selma, Alabama. It also happened in the northern city of Detroit during the mid-to-late 1960s, again and again and again. As in the South, when civilians filed complaints of police brutality, the Detroit Police Department blamed a subset of protesters in the crowd who were "unruly," who engaged in verbal "harassment" of the police, who threw "missiles" at them. Whether the civilians whom the police beat and brutalized during the subsequent riot control maneuvers, street sweeps, and other militarized assaults were the same individuals who had allegedly done these things did not ultimately matter to the DPD's justification of the use of force and process of near-automatic exoneration of officers accused of misconduct. Carl Parsell, the head of the DPOA union, argued that charges of police brutality were attempts to "overthrow" the government and that police officers in the streets had to have unquestioned freedom to use "proper force" to maintain "peace and order."

This section explores the controversies over the DPD's violent political assaults on young civil rights marchers from the Poor People's Campaign at Cobo Hall in May 1968 and then against young left-wing protesters at a George Wallace rally held in Cobo Hall that October. The formation of the Ad-Hoc Action Group after the first Cobo Hall attack marked the most important mobilization of white activists in the anti-police brutality campaign since the Adult Community Movement for Equality, which was also violently repressed by the Detroit Police Department, during 1965-1966. The white activists in the Ad-Hoc Action Group joined forces with civil rights and black power counterparts to call for a civilian review board to oversee the police department and punish police brutality, a movement that intensified after the DPD's whitewash of the internal investigations in both Cobo incidents. The radical vision that emerged from the racial conflicts between the DPD/DPOA union and political activists during 1968-1969 demanded full community control over an out-of-control, democratically unaccountable, racist, right-wing, and politically autonomous police department.

Sources

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

MaryAnn Mahaffey Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

William Serrin, "The DPOA: It Talks for Police," Detroit Free Press, April 20, 1969