Balduck Park Incident

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Detroit Police Department also targeted and brutalized white youth associated with the radical anti-Vietnam War movement and the burgeoning counterculture, in addition to their primary focus on criminalizing African American teenagers. Many countercultural white youth broke the drug laws, especially by smoking marijuana, and enforcement became a police priority in the late 1960s as the national war on drugs escalated under the Nixon administration. Youth identified with the counterculture also violated mainstream adult standards in terms of sexual liberation, as well as offending the conservative DPD with their radical politics.

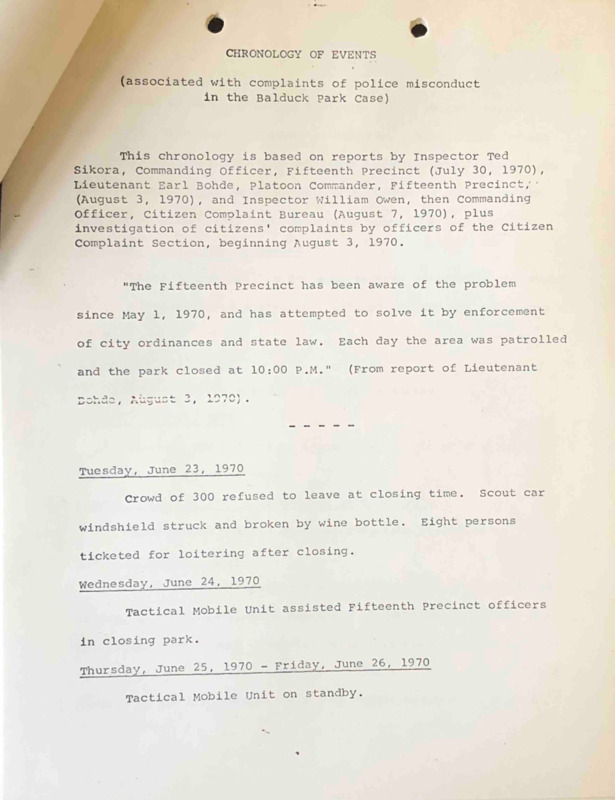

Police harassment and brutality was especially pronounced against countercultural youth in public spaces, especially public parks, which became a key battleground during this era. Residents of the neighborhoods surrounding city parks began to file hundreds of complaints with police alleging drug use, excessive noise, and other illicit and illegal activities by teenagers congregating in these public spaces. The police cracked down on white and nonwhite youth in multiple park locations, but Balduck Park on the far East Side of Detroit received the bulk of the complaints. In response, the 15th Precinct began patrolling the area and enforcing the city ordinance that closed public parks at 10:00 pm. In addition to citywide curfew regulations for youth under age 17, the DPD had the discretionary authority under the municipal code to make loitering arrests for "objectionable noise and disorderly conduct" in public parks, a category of criminalization that could mean anything an officer wanted it to mean.

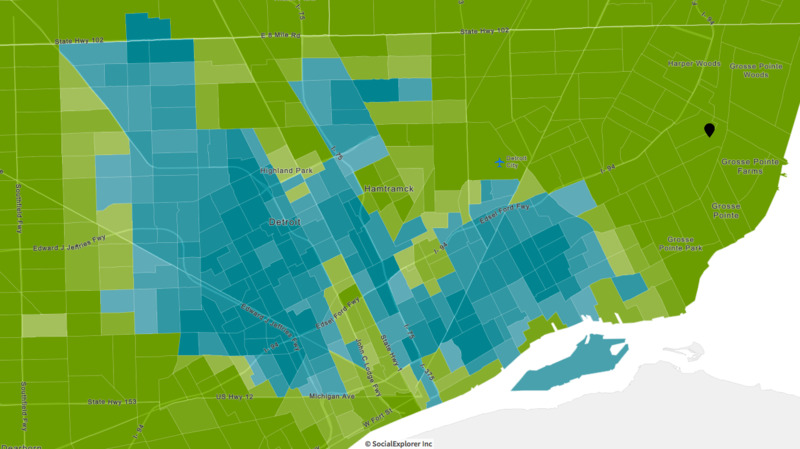

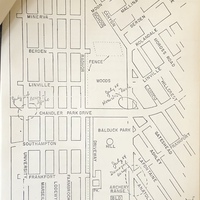

Balduck Park was located at the outer edge of the city limits, in all-white middle-class neighborhoods that were adjacent to some of the wealthiest suburbs in the Detroit metropolitan region, including Grosse Pointe (map at right). The white teenagers who congregated in Balduck Park included city residents from nearby and from neighborhoods across the city, and also countercultural suburban youth who rejected the dominant conservative politics of the time and understood that they would have more freedom from parental supervision in a Detroit location than in Grosse Pointe and similar communities. Balduck Park was as far away from Detroit's heavily policed poor African American neighborhoods as it was possibly to be while still remaining inside the city limits. Many of the Balduck Park youth who enthusiastically broke the drug laws and engaged in confrontational behavior with the police did so from a background of significant racial and class privilege, but they also found out the hard way what a brutal police crackdown was like.

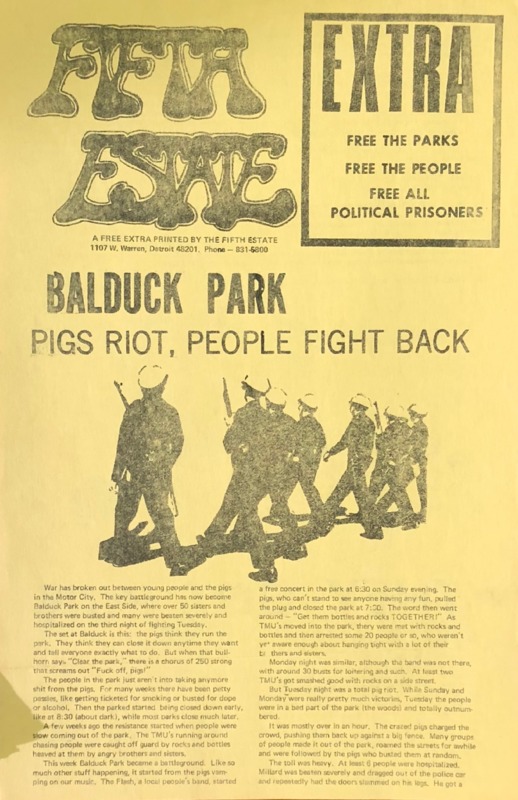

In the summer of 1970, Balduck Park became the site of frequent battles between white teenagers and the Tactical Mobile Unit, which had responsibility for "crowd control" and political demonstrations, including the ongoing brutal crackdowns on African American youth protesting in the junior and senior high schools. The running confrontations reached their climax from July 26-29, 1970, and the TMU ultimately cleared the park with extreme violence and caused many injuries to the teenagers gathered there. New Left organizations led by white radicals defended the Balduck Park youth, including the Fifth Estate underground newspaper (above) and the anti-police brutality Ad Hoc Action Group that had formed in 1968. The Ad Hoc Action Group formed a Peoples' Defense Committee to investigate the Balduck Park Incident, represent the arrested white youth, and demand prosecution of the guilty TMU officers. The DPD investigation found clear officer misconduct but in the end, almost no police officers were disciplined.

Criminalizing the Teenage Subculture

Tensions between white youth and law enforcement grew steadily in Balduck Park during the summer of 1970. Every afternoon and evening, crowds of at least 300, and often 800-1,000, youth ranging from 13 to 22 years in age gathered in the park. Residents of the surrounding neighborhood submitted many complaints about noise, litter, underage drinking, illegal drug use, and too many cars crowding the streets. A group of residents convinced the Detroit Parks Department to close Balduck Park two hours early, at 8:00 p.m., to discourage outsiders by banning parking in the evenings, and to restrict motorcycles on noise ordinance grounds.

The local DPD precinct immediately began enforcing these special new rules aggressively, handing out loitering tickets and often summoning the riot control police in the Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU). During a two-day period in June 1970, for example, police made more than 50 loitering arrests. Some of the Balduck Park youth refused to comply with the early 8:00 p.m. closing time, which they considered discriminatory and a targeted anti-youth policy to criminalize their subculture, leading to more arrests.

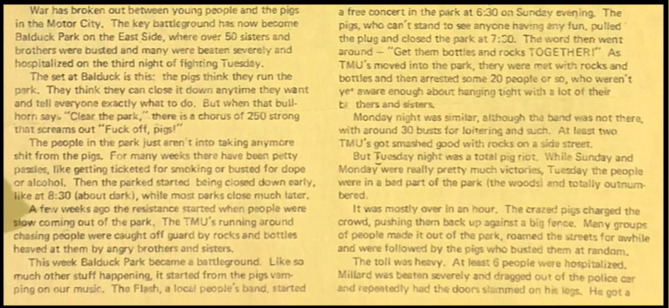

The police-youth confrontations continued to escalate during July 1970. On many summer Sundays, local bands played free concerts, another way to express defiance of the crackdown. The DPD often shut these concerts down early, ticketed youth for loitering, and engaged in acts of brutality in a number of episodes. Some of the youth in the park then fought back, throwing rocks and bottles at the TMU riot police and chanting, "fuck off, pigs," as the DPD shut Balduck Park down at or before 8:00 p.m. each summer night.

The tensions culminated in a four-day police operation to clear Balduck Park at the end of the month.

Sunday, July 26: The Balduck Park Committee sponsored a free concert featuring a local band, The Flash. The TMU shut the music down at 7:30 p.m., a half hour before the already premature closing time imposed by the Parks Department. Some teenagers refused to leave and shouted the "fuck off, pigs," chant and threw rocks and bottles at TMU officers. Around 20 youth were arrested and others received loitering citations.

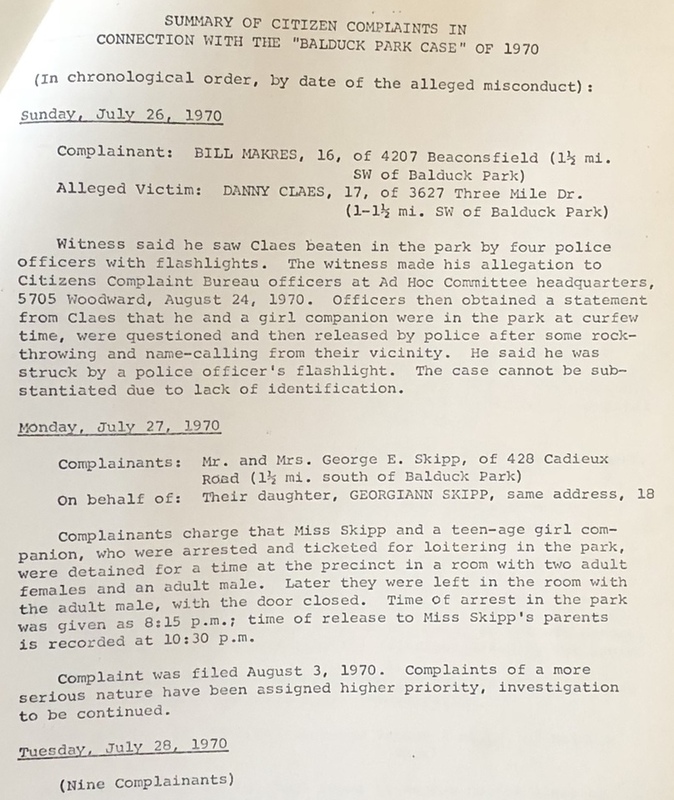

Danny Claes, 17, was beaten by four officers with flashlights during the Sunday evening shutdown and filed a complaint (gallery, below left). The DPD said the allegation could not be substantiated because of a "lack of identification" of the individual officers (who generally removed their badges, to prevent such identification, during "crowd control" actions).

Monday, July 27: There was no live music, but the TMU arrested around 15 youth and ticketed others for loitering. The Fifth Estate boasted that youth rebels hit at least two TMU officers with rocks, which might well explain the disproportionate vengeance taken the next day by the Tactical Mobile Unit.

Clearing the Park

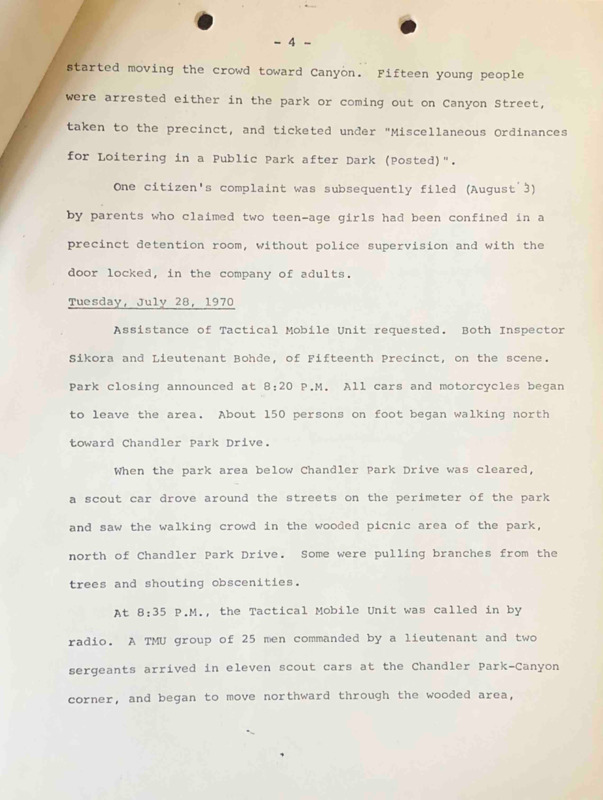

Tuesday, July 28: A massive TMU operation cleared Balduck Park with extreme brutality and violence. In a coordinated maneuver, TMU police in cars surrounded the park on several sides and trapped several hundred youth, many of whom were seeking to comply with the 7:45 p.m. order to leave, against a fence on one of its borders. TMU police in riot gear exited their cars and charged the youth. Many officers were carrying unauthorized weapons, such as baseball bats or clubs with homemade affixed bayonets. Teenagers began trying to escape in multiple directions, and TMU police and other reinforcements pursued them in cars and on foot, beating and kicking many of the youth. Other TMU officers attacked youth who were already in their cars, trying to leave, when the operation began.

The police operation lasted for about an hour and a half, resulting in around 85 arrests and at least 15 serious injuries to the youth who were in Balduck Park. Every single young person involved was white. Here are a few of their stories, taken from formal complaints and coverage in radical newspapers:

- Annie, 13, was beaten and had a fractured skull.

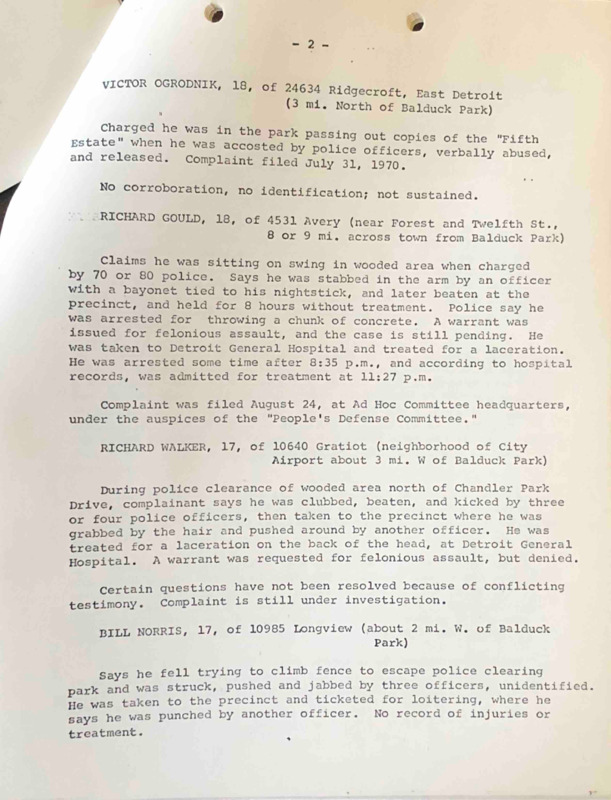

- Richard G., 18, was charged by police while sitting on a swing and stabbed with a bayonet, arrested and beaten at the precinct, and held for 8 hours without treatment.

- Richard W., 17, was beaten with clubs and kicked by 3 or 4 TMU officers and then arrested on a false felonious assault charge.

- Bill, 17, was stabbed and punched by officers at the fence and later punched at the precinct.

- John, 21, and Dale, 20, were in Dale's car trying to leave as instructed when an officer broke the windshield of the car and smashed John in the head. John fled and was caught and beaten by several officers, suffering a lacerated scalp. Dale was dragged out of the car and beaten when he surrendered to be handcuffed, breaking his arm and several fingers, and later beaten at the precinct after being arrested on a false assault charge. Both were hospitalized.

- Mark, 17, left the park as instructed and was several blocks away when multiple police jumped out of their car to beat, kick, and arrest him. He received a loitering citation.

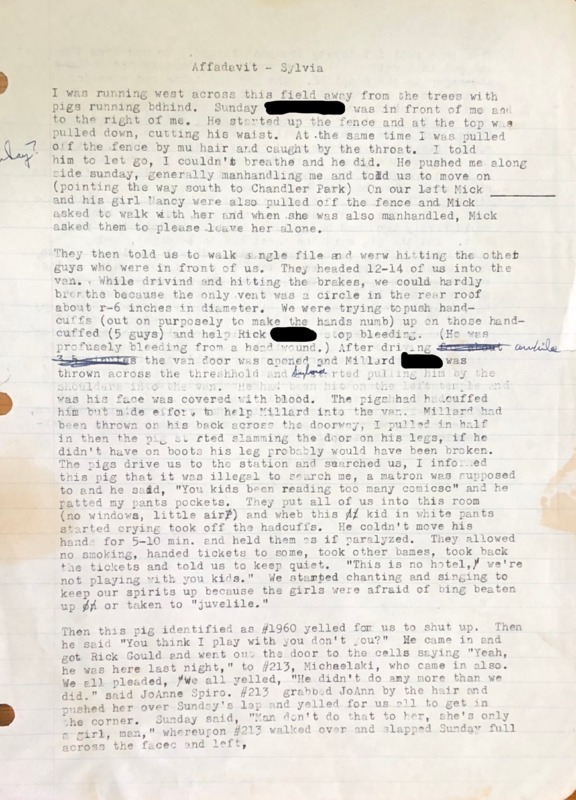

- Sylvia and three friends were climbing the fence to escape the assault when they were roughly pulled down and arrested by police who beat the males in the park and then threw them all into a van, with several bleeding profusely from the head. In lockup, a male officer searched her, which was against DPD policy, and physically assaulted some of her friends (gallery, second from left).

The arrested youth were taken to the 15th Precinct, not allowed to make phone calls, not informed of their legal rights, not treated for their injuries, and held for up to 8 hours. The police booked most of them for felonious assault, a common retaliatory tactic designed to justify police brutality as alleged self-defense. One arrested male who sought to inform others of their legal rights was taken to a cell and beaten by an officer who had removed his badge and identification. Three of the females who had been arrested accused the police of "molesting" them inside the precinct jail cell. The police beat at least five other people in the precinct station and then released most of them without charges, apparently because the prosecutor declined to pursue the cases when news of the incident got out. Many of those released then sought hospital treatment.

Wednesday, July 29: About 300 youth returned to the park, and some allegedly threw rocks and bottles when the TMU shut it down. Police made several more arrests, issued 17 loitering tickets, and again beat youth who were trying to drive away in their cars, also damaging multiple vehicles with nightsticks. A police officer attacked a man who lived across the street from the park and was on his porch taking pictures of the assault, beating him and destroying the camera. Among the complaints filed:

- Haskell, 17, was beaten and arrested, then prosecuted for assault, but acquitted.

- George, 17, and Ronald, 18, were in their car leaving when police ticketed them for loitering and then assaulted them with blackjacks.

- Nine youth filed complaints that police officers badly damaged their vehicles as they were stuck in a traffic jam trying to leave the park.

The Balduck Park Investigation

The Ad Hoc Action Group, which had been formed by white New Left radicals in summer 1968 to protest police brutality against African Americans and political activists, took the lead in defending the white youth brutalized in Balduck Park and especially those wrongfully arrested for felonious assault against the police. The Ad Hoc Action Group immediately collected affidavists from teenagers who had been attacked in the park and at the precinct station and helped them file two dozen formal charges with the Citizen Complaint Bureau (above gallery). When the DPD claimed that multiple allegations were "unsubstantiated," the Ad Hoc Action Group accused the CCB of an inability to conduct "impartial" investigations and an unwillingness to refer police officers for criminal prosecution. The Ad Hoc Action Group stated that because the DPD always found police force to be "reasonable," only a civilian review panel could fairly investigate the Balduck Park assault.

The Ad Hoc Action Group formed the People's Defense Committee to provide a legal defense for the teenagers who faced felonious assault charges and prosecution for other alleged violations, such as trespassing. The People's Defense Committee said that the arrests were "illegal and arbitrary" and also mainly targeted youth who were trying to leave the park and seeking to comply with police orders. They charged the city government with "permitting the police to savagely and brutally attack" both black and white youth engaged in political protest against an unjust system:

The People's Defense Committee also blamed the deliberately brutal tactics and quasi-official procedures of the Tactical Mobile Unit for the violence in Balduck Park, from "their training to chase people into a fence" to the common retaliatory practice "to beat people severely and then charge them with felonious assault."

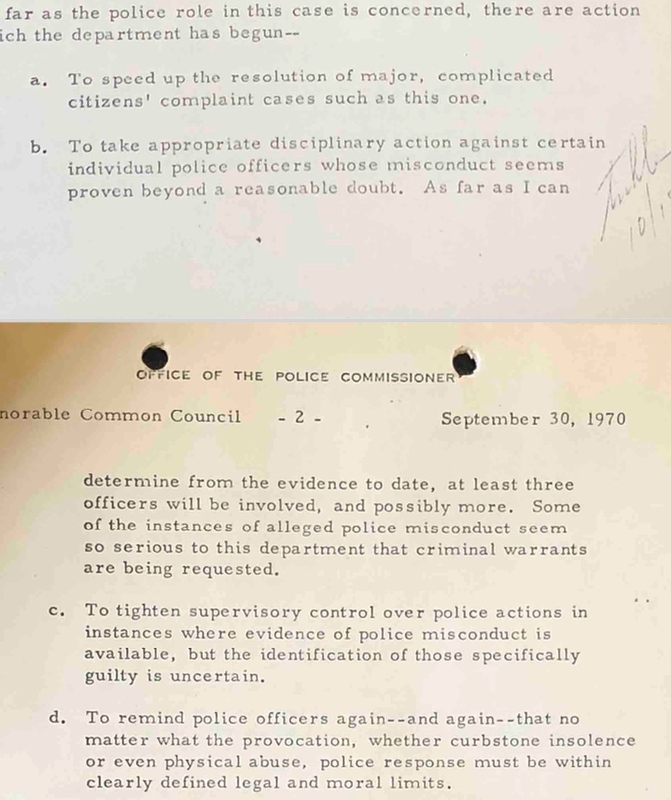

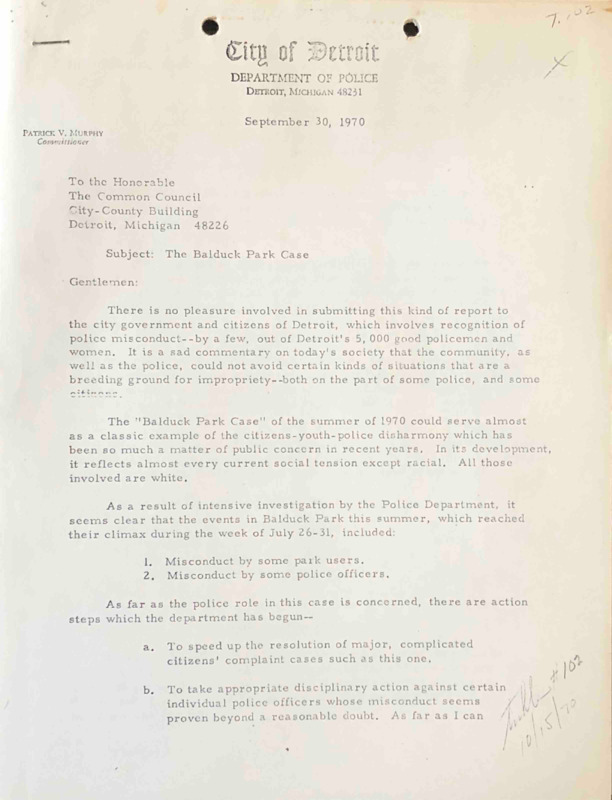

Commissioner Patrick Murphy, who had been recently appointed and who had promised to discipline and even criminally charge officers who engaged in "genuine" misconduct, pledged that the Citizen Complaint Bureau would conduct a thorough investigation. The CCB interviewed more than 70 people, including all of the youth who filed complaints, many of the police officers involved, and potential eyewitnesses from the surrounding neighborhood. Two months after the event, Commissioner Murphy submitted the CCB findings and his own analysis of the Balduck Park Incident to the Detroit Common Council (gallery below).

Commissioner Murphy's report acknowledged that "a few" DPD officers, out of a force 5,000 strong, were guilty of misconduct in the Balduck Park Incident. He very clearly blamed the misconduct by the disorderly youth for provoking the incident by verbally abusing police officers and throwing rocks and bottles at them. Murphy said it was "understandable" but "regrettable" that police officers assaulted by the park youth might have responded with excessive force to these provocations. He also explained that the CCB inquiry could not substantiate most of the allegations of brutality against police officers, for three reasons:

- Many youth could not identify the individual officers, in part because they had removed their identification, which was a "supervisory control" problem the DPD needed to address.

- Many allegations came down to the word of the youth complainant versus the word of the officer, and therefore could not be substantiated without corroboration.

- Multiple allegations of police brutality, and even some confirmed cases of serious injuries caused by police, could be considered "justifiable" because the citizens were resisting arrest, according to claims by officers involved.

Despite these procedural obstacles, which made findings of physical brutality almost impossible, Murphy stated that there was evidence that three officers should be disciplined, and possibly referred for criminal prosecution. The main misconduct that he identified was "malicious destruction of property" for clubbing the vehicles of the youth stuck in traffic on July 29, the day after the main TMU operation. The CCB only found one allegation of physical brutality in the July 28 park sweep substantiated, and none of the allegations of brutality in precinct lockup. In conclusion, Murphy stated that the DPD must:

This was not a complete whitewash, but it was close. It is clear that the TMU operation was a premeditated attack on a group of youth whose main crime was hanging out in a public park and listening to music, and being associated with the countercultural "hippie" lifestyle, with a subset drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. The TMU officers brought homemade, unauthorized weapons and beat random teenagers and young adults after trapping them against a fence in a planned flanking multi-front assault. There was zero correlation between the small number of youth who had thrown rocks and bottles on previous days, in protest of the early and selectively enforced shutdowns of their right to freedom of assembly in a public park, and the much larger group of youth whom the TMU and other DPD officers assaulted and arrested on July 28. Many of the brutalized youth were clearly seeking to comply with the orders to leave, and a number were in their cars trying to drive away as instructed. The CCB investigation focused more on the damage done by police to vehicles than on the numerous complaints that police beat and kicked youth in the park, incidents that could not be "corroborated" even when multiple youth testified to the same account. The CCB report had nothing to say about the premeditated and retaliatory assaults in the precinct lockup, out of public view altogether.

Read the DPD's internal investigation in the gallery below (the citizen complaints from this investigation are in the above gallery).

A Police Riot

The Balduck Park investigation was still very unusual because the DPD did concede that some officer misconduct occurred, but it placed responsibility on "a few" officers, and even more on the youth who allegedly provoked them, with no consideration of the role played by the department's militarized policies of "crowd control" and "demonstration control" and its commitment to using extreme violence to dominate public space against political protesters and in this case also cultural dissidents. The TMU mobilized its riot control operation, complete with extralegal weapons, but there was no riot in the park at all, except the one by the police themselves.

While some Balduck Park youth during the summer of 1970 were breaking the alcohol and drug laws, and using obscene language, citizen illegality and rudeness does not justify police illegality--meaning collective and coordinated DPD illegality and not just individual officer misconduct. Although the DPD justified its actions because of the requests of neighborhood residents, it is clear that police officers viewed countercultural white youth as a political threat, who deserved to be criminalized for their desire to congregate in public and then when the police desired, suppressed with force. Witnesses heard police officers saying, "let's smash those hippie heads," among other expressions of premeditated vengeance. The CCB investigation itself acknowledged that the TMU removed their badges and identifying information before sweeping the park, which is not something that police officers who planned to operate within the law would have any reason to do.

The police cover-up of officer violence and criminality also fit the longstanding pattern, both in terms of what happened in the park and what did not happen during the internal investigation. The arrests of innocent youth for "felonious assault" were clearly false, retaliatory, and designed to cover the tracks of police brutality and misconduct. The idea that unarmed teenagers would physically assault armed riot police who were closing them down in tight formation and with extreme force, corraling them against a fence and dragging them out of their cars, is almost too preposterous to take seriously, and yet this was a main rationale that the CCB and Commissioner Murphy used to find that most of the brutality allegations could not be substantiated, because the youth may have been "resisting arrest." On this note, the CCB investigation found no credible evidence that any of the individual youth arrested, and that any of the youth who filed complaints, had attacked police or thrown rocks and bottles at them. But the word of the officers still almost always prevailed over the word of the civilians. The "Blue Curtain" code of silence thwarted the investigation, as always, making it even more difficult to identify some of the individual officers involved. Members of the police department refused to implicate one another under any circumstances, and yet Commissioner Murphy did not mention this obstacle in his recommendations for police reform after Balduck Park Incident.

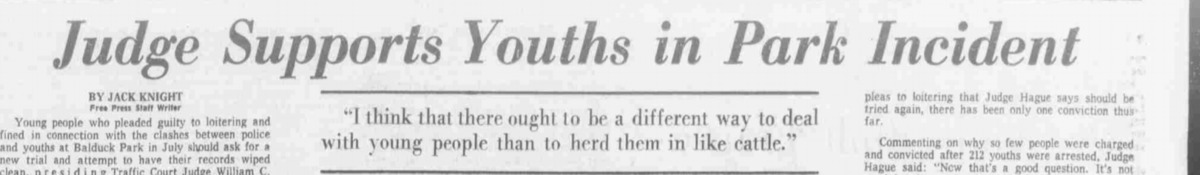

All of the youth involved in the Balduck Park Incident were white, as Commissioner Murphy noted in his report. This undoubtedly shaped the atypically thorough DPD internal investigation as well as the public and government perception of the events. The Detroit Common Council demanded a full investigation. The Wayne County prosecutor's office declined to press charges on a number of the assault cases recommended by the police. The white youth who were prosecuted were generally acquitted, with one local judge even finding that those who had pleaded guilty and paid loitering citations were actually innocent and that the DPD had wrongfully sought to "make criminals of young people in mass numbers."

Coda: Continued Youth Criminalization

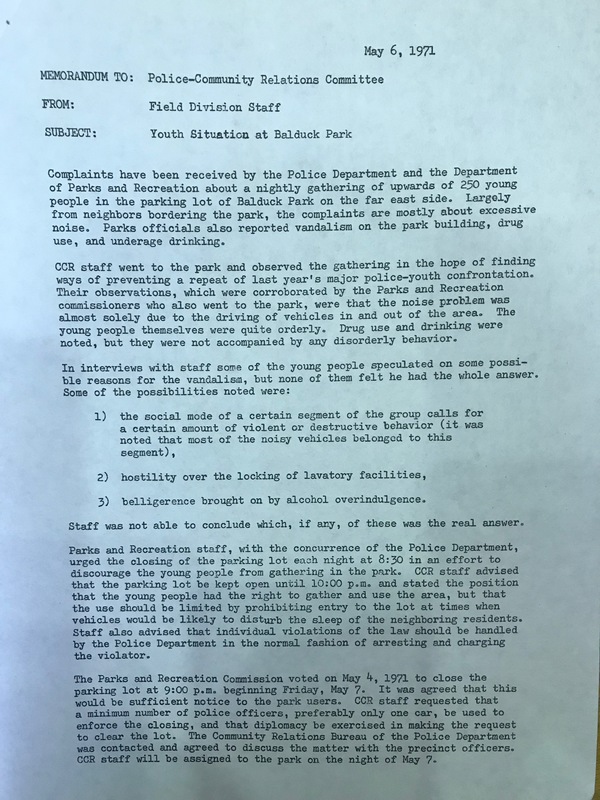

Young white people kept returning to Balduck Park after the police riot of July 28, 1970. Some neighbors in the area also kept complaining to the police, who kept harassing and criminalizing the youth who congregated in the park. In May 1971, the Detroit Commission on Community Relations investigated and found that most of the youth who gathered there were peaceful and did not appreciate the small faction who sought to be disruptive. The DCCR recommended that the Parks Department and the DPD stop selectively criminalizing the youth in Balduck Park with the early closing time, and that the police department reconsider its approach and monitor the park with a single squad car instead of TMU riot police. This did not happen. The DCCR also observed that, as a constitutional matter, "young people had the right to gather and use the area" (above right).

In June 1971, organizers among the white countercultural youth formed the Balduck Park Committee to "police the park themselves" and promised to clean up the litter and ban hard drugs such as heroin. At least 500 "freeks" signed a pledge to abide by this internal code of coduct. The Balduck Park Committee did not believe that marijuana and LSD were harmful and declined to enforce any prohibition against recreational use of these psychedelics. They also resisted noise restrictions designed to prevent bands from playing. In addition to the DCCR, several other civic and religious groups got involved to seek to broker a peace between the Balduck Park youth and the police.

Then on June 28, 1971, more than 100 officers in the Tactical Mobile Unit in riot control gear descended on the park, with a helicopter buzzing overhead, in a military-style operation personally overseen by Commissioner John Nichols. The massive show of police force resulted in the arrests of 11 teenagers for marijuana or LSD possession, and another person for possession of a hypodermic needle. The police expected to find heroin but did not. The militarized drug sweep did not result in as many brutality allegations as the incident the previous summer, but it confirmed the continued police criminalization of the countercultural white youth who gathered every summer evening on the far East Side of Detroit.

Sources:

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR)/Human Rights Department Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Roman S. Gribbs Mayoral Records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Free Press, November 11, 1970

Ann Arbor Sun, July 9, 1971