The Brutal Murder of Cynthia Scott

July 5, 1963: "Fatal Shooting of Cynthia Scott"

Cynthia Scott was walking down the street when DPD Patrolman Theodore Spicher accosted her, sought to arrest her without cause, and then shot her twice as she walked away, ending her life.

Scott, a 24-year-old African American woman, was walking home accompanied by Charles Marshall, a 21-year-old African American man, when the encounter began at the intersection of John R. and Edmund Place around 3:00 a.m. on July 5, 1963. Spicher, a 28-year-old white police officer with four years on the force, was working the graveyard shift with his partner, Patrolman Robert Marshall, also a white man, when he made the decision to pull over and seek to place Cynthia Scott under arrest, setting the events that led to her death in motion.

From that moment, the official police account differs substantially from the accounts of eyewitnesses, and also differs substantially from the preponderance of evidence in the historical record, which reveals a cover-up by the DPD and the Wayne County prosecutor, as outlined below. This investigation is based on the DPD Homicide Bureau file on Cynthia Scott (view full file here-note: 248 MB), obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by Professor David Goldberg of Wayne State University; on the reporting of Detroit newspapers, most importantly the Michigan Chronicle; on the exposes done at the time by African American organizations; and on other archival collections in the Reuther Library at Wayne State.

Cynthia Scott Broady, known as Cynthia Scott, was a daughter, a wife, and a young African American woman who grew up in Detroit. She also was a sex worker--a "known prostitute" in the unsympathetic portrait of Detroit's white newspapers, "a colored female I recognized as a known prostitute" in the report of her homicide submitted by Theodore Spicher.

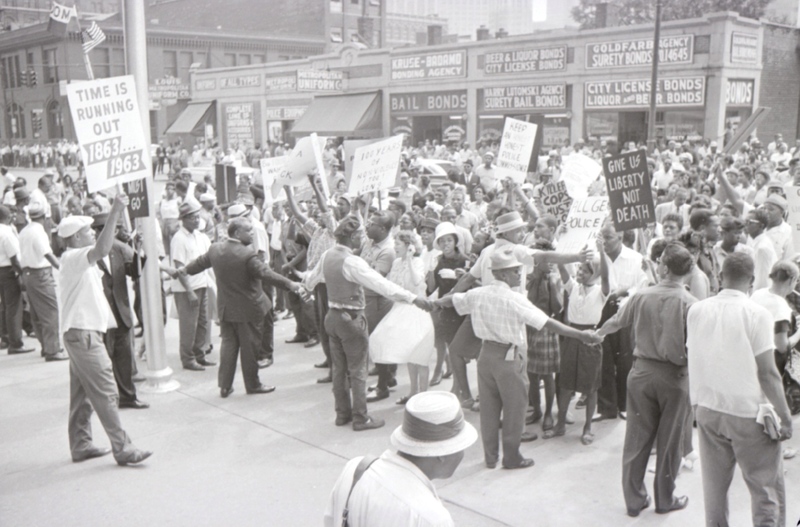

In an extraordinary turn of events, the killing of Cynthia Scott by Theodore Spicher led to a major escalation of the anti-police brutality movement in Detroit. One week after the incident, on the day after the county prosecutor ruled the shooting a justifiable homicide, around 2,500 African Americans joined a demonstration at the DPD's downtown headquarters to protest police violence (right). The traditional middle-class civil rights organizations, the NAACP and Urban League, had nothing to do with this outpouring of anger on the streets, the first in a series of anti-police brutality demonstrations in the summer of 1963. Instead, the campaign for justice for Cynthia Scott was led by the Detroit Council for Human Rights, a newer, militant counterpoint to the NAACP; by churches with a black nationalist orientation, especially Rev. Albert Cleage's Shrine of the Black Madonna; by radical young black activists in recently formed groups called GOAL and UHURU; and by regular working-class black people, especially women.

Cynthia Scott: The Bigger Picture

The Detroit Police Department and the Wayne County prosecutor covered up the circumstances of the murder of Cynthia Scott. Patrolman Spicher and Patrolman Marshall fabricated a cover story that portrayed her as the armed aggressor, and the DPD Homicide Bureau ignored and suppressed countervailing evidence to promote this version, including multiple eyewitness testimonies and contradictions in the initial accounts of the two officers. The Wayne County prosecutor, Samuel Olsen, ruled Theodore Spicher's shooting of Cynthia Scott a "justifiable homicide," as always happened when police officers killed African Americans, and indeed almost every time DPD officers killed anyone, in the city of Detroit. But this time, a segment of the African American community refused to accept the prosecutor's judgment, even for a victim with a criminal record as a "known prostitute." Olsen was, according to the sign held by one of the protesters in the July 13 demonstration, "Defense Attorney: For Murderers!"

Historical responsibility for the death of Cynthia Scott does not lie with Patrolman Theodore Spicher alone. As analyzed below and on the next page, the Detroit Police Department's longstanding, pervasive, and illegal policy of making investigative arrests precipitated the encounter. Spicher's effort to arrest Cynthia Scott on suspicion of larceny was a clear violation of the Detroit Police Manual, revised in 1962, which did not allow an officer to make a misdemeanor arrest without a warrant, unless committed in the officer's presence, and required "probable or reasonable cause" for warrantless felony arrests (read full policy here). Most if not all of Cynthia Scott's nine prior arrests on prostitution-related charges were also illegal, as the DPD and the Wayne County prosecutor belatedly conceded in 1966. There is also evidence that Spicher's harassment of Cynthia Scott was part of a broader police corruption racket that collected payoffs from sex workers, drug dealers, and others involved in the so-called vice markets. Multiple police investigators, not just Spicher and his parter Robert Marshall, discounted eyewitness testimony and advanced the cover-up story that blamed Cynthia Scott and not Theodore Spicher for her death. There is smoking gun evidence in the DPD file of discrepancies between Spicher's and Marshall's initial accounts that the Homicide Bureau helped the officers belatedly reconcile. The mainstream newspapers, the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News, also criminalized Cynthia Scott and reflexively took the side of law enforcement, skewing public perceptions of the encounter.

The DPD's permissive use of force policies and pattern of failure to investigate police misconduct in black neighborhoods, combined with the prosecutor's perfunctory investigation and automatic exoneration of police accused of criminal acts of brutality and murder against black citizens, mean that the killing of Cynthia Scott cannot be attributed to the actions of a single 'bad apple' police officer on the street. The civil courts also thwarted justice after Cynthia's mother, Lillian Scott, filed a $5 million wrongful death lawsuit against the city of Detroit and Theodore Spicher. The city government, under the liberal Cavanagh administration, then moved to indemnify police officers from personal liability in civil lawsuits involving their official duties, again sending the message that the state sanctioned police violence and would justify even murder when the victims were members of the African American community in Detroit.

What Really Happened? The Eyewitness Accounts

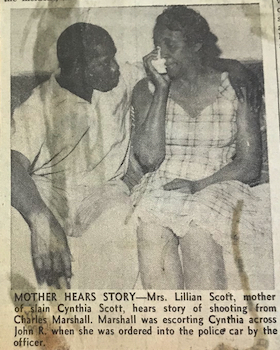

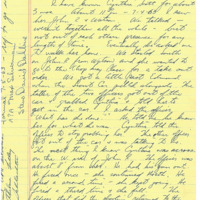

Charles Marshall was with Cynthia Scott when she died, and since she cannot speak directly for herself, the story starts with him. Marshall told his account to the DPD's Homicide Bureau investigators, who dismissed it as "biased," to the Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's African American weekly, and also to Cynthia's distraught mother Lillian, at right. According to Marshall, who was a friend of Cynthia's, he was out late celebrating on the 4th of July when he ran into her on the street at 2:45 a.m. and she asked him to walk her home. (In the DPD account, Marshall had been socializing with Cynthia Scott since 11:45 p.m.). On their way, Patrolman Spicher jumped out of a car and ordered Cynthia to get into the vehicle. Cynthia Scott objected, saying she had done nothing wrong, and Charles Marshall told Spicher he would have to arrest him as well then. Patrolman Robert Marshall (no relation) then frisked Charles Marshall against the side of the police car and took his jackknife. During the search, Patrolman Spicher grabbed Cynthia, but she broke away, saying "I'm not getting in the car. I haven't done anything, why should I get in the car?" Cynthia started walking away, and Spicher then pulled out his gun and fired at her once, which Marshall thought was only a warning shot. Cynthia kept walking away, and Spicher fired twice more, and then she fell face down onto the sidewalk.

Charles Marshall then saw the two officers put Cynthia Scott in their patrol car to take her to the hospital. Marshall continued to Cynthia's residence and told her husband, Oates, about the shooting. They went to Receiving Hospital together and found out she had died. Then Marshall went to the police station to give a statement to the Homicide Bureau. While there, he ran into Patrolman Robert Marshall, who claimed that Cynthia Scott had cut him with a knife and showed him a torn shirt sleeve as evidence. Charles Marshall disputed this account and told the Homicide Bureau that Cynthia Scott was unarmed and shot in the back while walking away by Theodore Spicher. The DPD arrested Marshall for carrying a concealed weapon, the jackknife, which was not illegal to possess, but later dropped the charges.

The other eyewitnesses, all but one African American, tell similar versions of Marshall's account, except for the single white witness. Several also state that the two officers gave themselves minor cuts with a knife, presumably to concoct a cover story.

- Rev. Alfonso Campbell, pastor of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, was driving home from a late night at the theater and saw a woman [Cynthia Scott] "talking to a policeman and then turn and start to walk away. At that point, the policeman fired one shot and, while the woman continued to walk away, he fired two more shots directly at her." The woman then fell to the ground and, Campbell emphasized, never turned back around to confront the officer. (Campbell volunteered his story to the Michigan Chronicle; the DPD Homicide Bureau did not interview him).

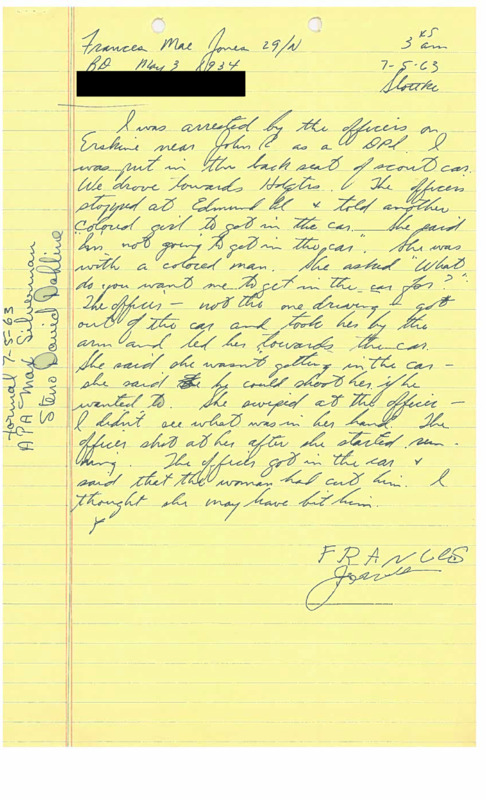

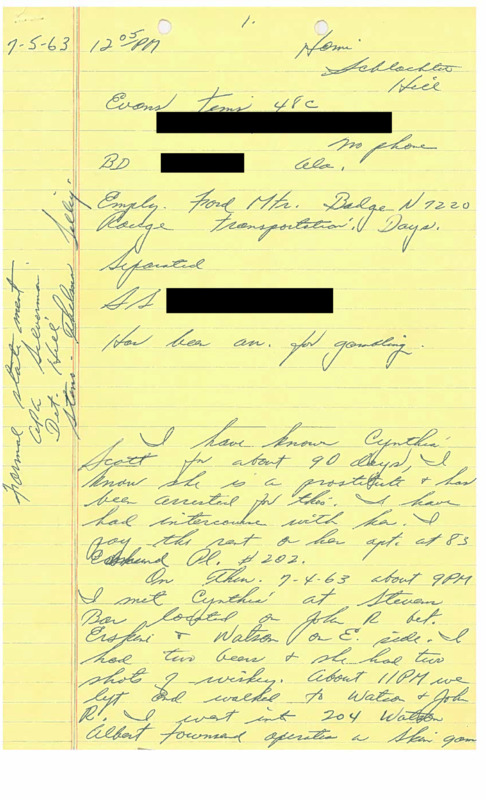

- Frances Mae Jones was in the back of the police car, under arrest, when Spicher pulled over to talk to "a man and woman on the street." The woman refused to get into the car, "so the man shot her. She started running. He fired two or three times, then she fell." Miss Jones also said she later overheard Spicher say that the woman had cut him, but she never saw that happen.

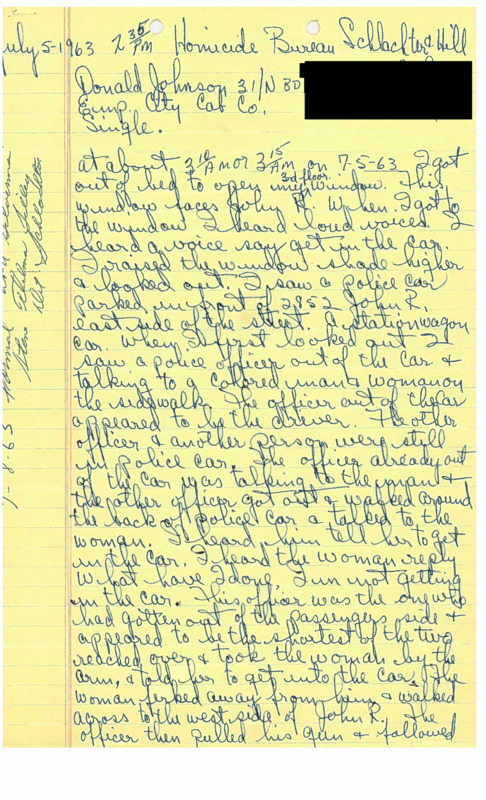

- Donald P. Johnson, a cab driver, was watching the encounter from his apartment and saw a woman walking away from a police officer who drew his gun and said, "If you take another step, I'll shoot you." The woman said, "You will just have to shoot me because I'm going home." The officer shot once and then "shot two more times while she was still moving after the first shot." Then the officer "walked over to her and bent over her," and appeared to take something from her hand. (Johnson mistakenly identified Robert Marshall as the shooter).

- Robert Leo Farr stated that a police officer was "talking to the lady" who refused to get into the car, and then the officer pulled out his gun and said, "If you don't get in the car you black bitch, I'll kill you." The woman then began walking away, and the officer shot at her three times. Farr also stated that the officer then walked over to the woman lying on the ground, took a knife out of her purse, and slashed his left hand with it. Then the officer took the same knife and cut the other officer's shirt.

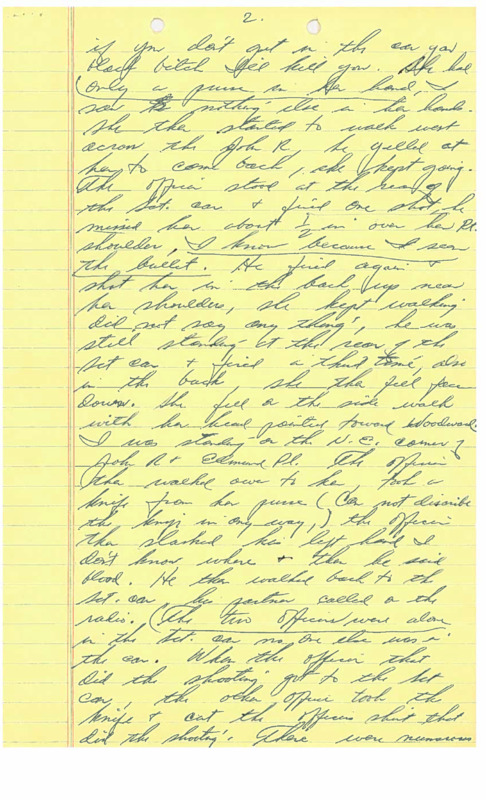

- Bernice Garland, watching from her third-story apartment, said a police officer shot Cynthia Scott, whom she knew, multiple times as she was walking away. The officer then went and leaned over the body, "you could see him doing something to his wrist," and then stood up and announced that the woman "cut me, I had to shoot her." (Garland also mistakenly identified "the shorter officer"--Robert Marshall--as the shooter).

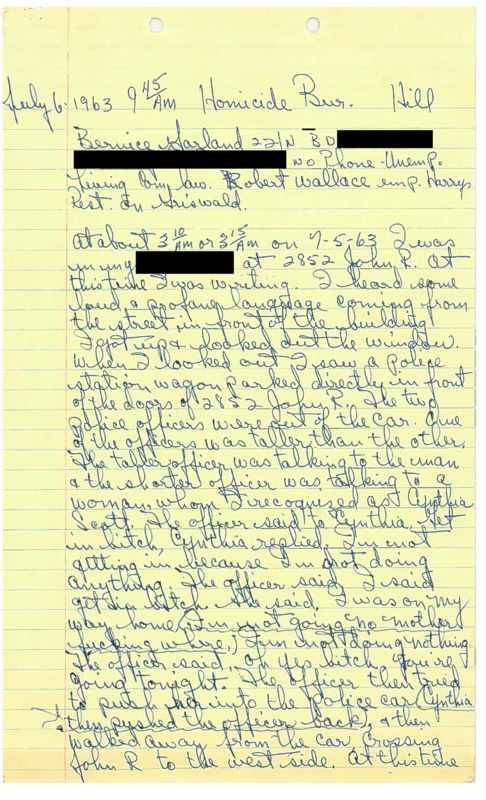

- Evans Tims stated that Cynthia Scott, whom he knew, was walking away when the officer yelled "halt" twice and then fired three times, and "she fell flat on her face." Tims also stated that Cynthia Scott carried a black-handled pocket knife for protection, but he did not see it in her hand.

- Joseph F. Maiorano, a white man who lived in suburban Roseville, said he was driving home when he heard gunfire, stopped his car, saw a police officer with a gun and a woman "lying face down," decided to walk over to get a closer look, and saw that the woman had "a knife in her hand with the blade open." Maiorano, who did not claim to witness the encounter itself, provided the only eyewitness statement potentially exculpatory for the police officers.

Gallery: Civilian witness accounts drawn from the sources below: investigation by the Michigan Chronicle, report by Detroit Free Press (combining statements to DPD and to prosecutor), the DPD Homicide Bureau's summary of witness statements, and the original hand-written versions found in the DPD Homicide Bureau file released under FOIA. Readers are invited to review these and decide for themselves what happened.

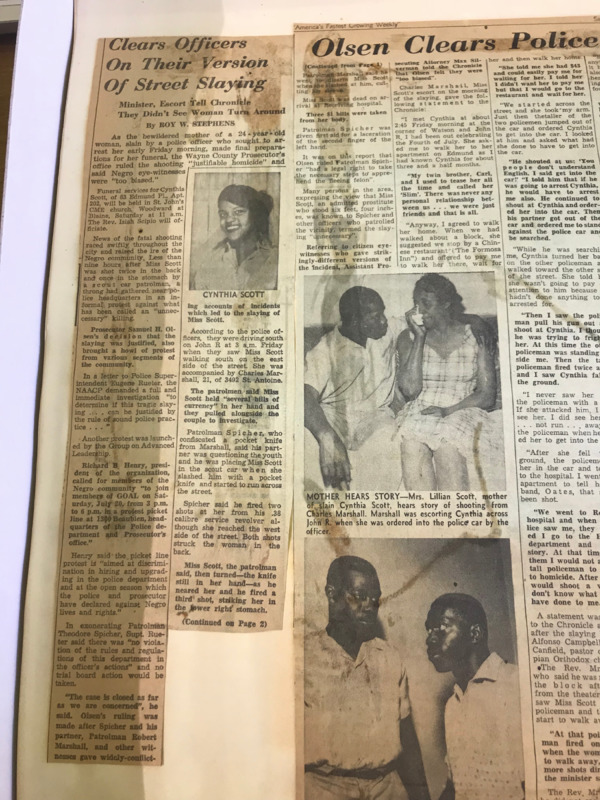

Note on Media Coverage: The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit's African American weekly, presented the eyewitness testimony, particularly from Charles Marshall and Rev. Alfonso Campbell, in coverage that was skeptical of the official law enforcement account (above top left). The Chronicle also interviewed Lillian Scott and used a family photograph of Cynthia Scott, along with the sympathetic photograph of Cynthia's mother and Charles Marshall, both reproduced here, in its coverage. The Chronicle additionally reported that Officer Theodore Spicher had recently assaulted a close friend of the Scott family, James Grendaws, a 40-year-old African American factory worker, after pulling him over on the highway. According to five witnesses, Grendaws asked why he had been stopped, and Spicher beat him and then arrested him for resisting arrest. The DPD dropped this charge against Grendaws when he agreed to withdraw his allegation of police brutality.

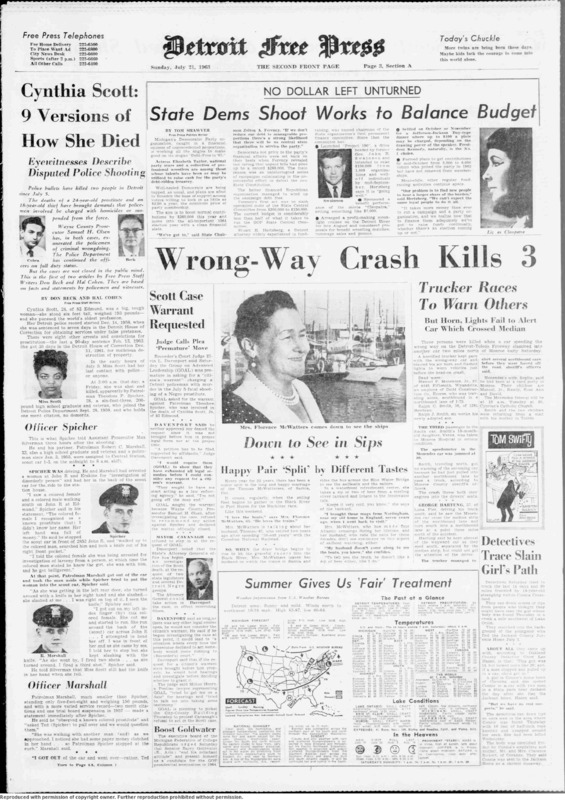

By contrast, the Detroit Free Press's main investigative piece, "Cynthia Scott: 9 Versions of How She Died" (above, top middle) did not run until much later, after the street protests elevated attention to the case, and it relied exclusively on the police and prosecutor reports. The Free Press article started by calling Cynthia Scott "a big, tough woman--she stook six feet tall, weighed 193 pounds--and she pursued the world's oldest profession." The article then detailed Cynthia Scott's nine previous arrests for prostitution and included her police mug shot. Next, the Free Press article provided the official DPD photographs of Officers Spicher and Marshall and included their accounts first, before the contradictory eyewitness testimony. The Free Press also reported that Theodore Spicher was a military veteran and had no disciplinary record on the DPD--portraying him as a model police officer.

What Didn't Happen: The Police and Prosecutor Cover-Up

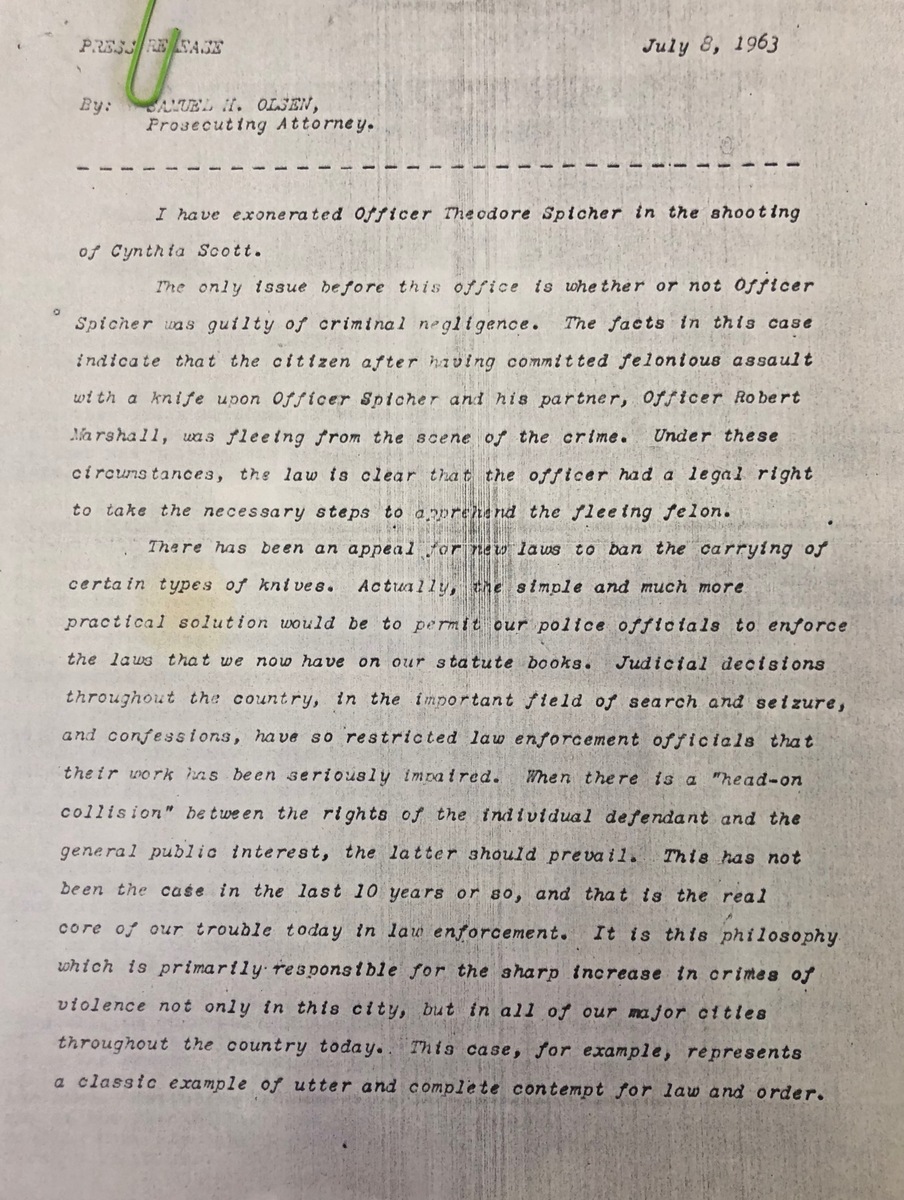

The Detroit Police Department and the Wayne County prosecutor's office covered up Theodore Spicher's murder of Cynthia Scott by portraying her as a career criminal and framing her as an armed aggressor and "fleeing felon." Neither the DPD nor the prosecutor seemed to care that Spicher's initial decision to arrest Cynthia Scott for "investigation of larceny" was an illegal violation of Detroit Police Manual policies (below right). According to prosecutor Samuel Olsen, Patrolman Spicher had "a legal right to take the necessary steps to apprehend the fleeing felon." Cynthia Scott's knife attack on a police officer seeking to defend the public safety, Olsen continued, "represents a classic example of utter and complete contempt for law and order." The killing of Cynthia Scott was a "justifiable homicide."

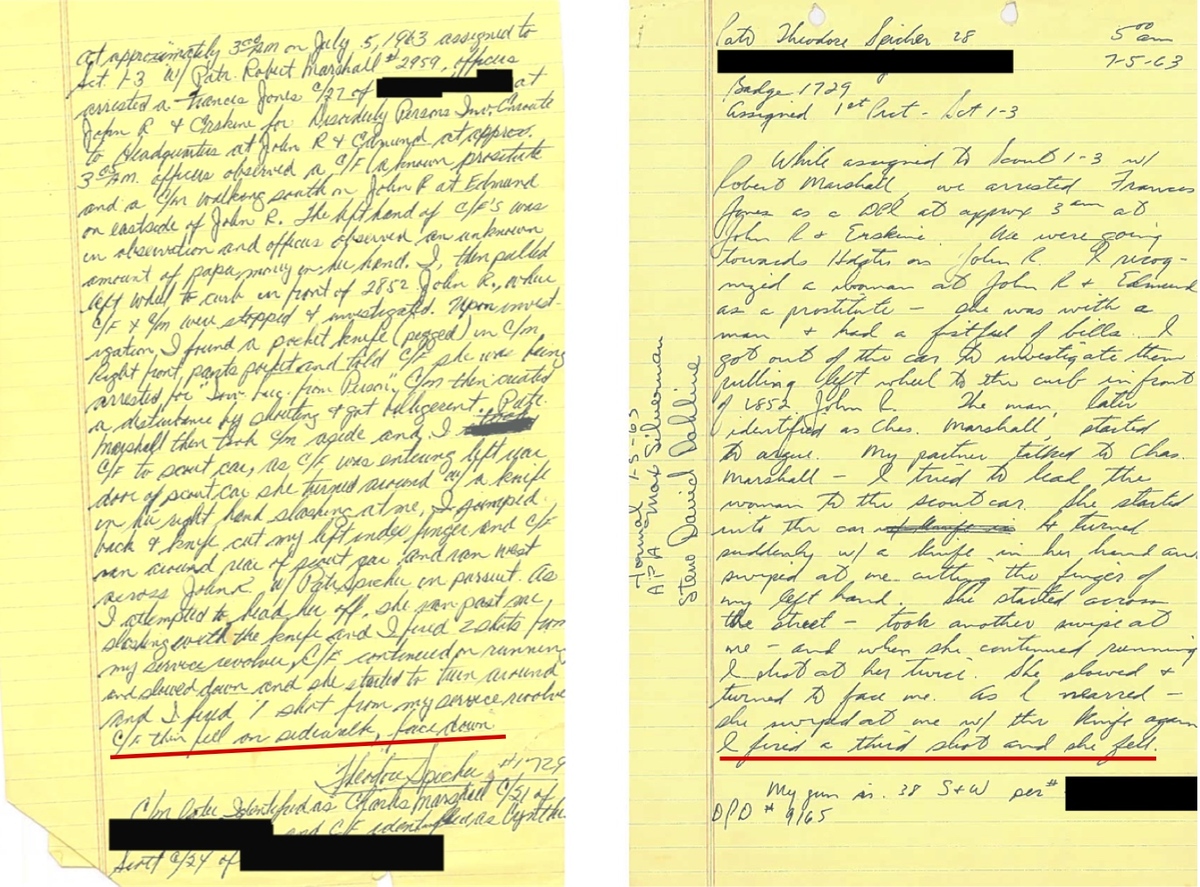

The DPD Homicide Bureau also smoothed over clear discrepancies in the initial statements by Patrolman Spicher and Patrolman Marshall, in particular regarding what happened after Spicher shot Cynthia Scott and she fell "face down" on the ground, as multiple police officers and other witnesses reported (see below). The DPD Homicide Bureau's official report (Spicher/Marshall excerpt, at right) is illogical on this key point, stating that Cynthia Scott fell "face down" from the bullet that killed her and then that she subsequently slashed at Robert Marshall with her knife, in an obvious attempt to reconcile the two officers' initially contradictory cover stories. The Wayne County prosecutor's "investigation" made no attempt to ask either officer any questions designed to do anything more than validate their cover stories.

Patrolman Theodore Spicher stated that he and his partner were taking a woman [Frances Mae Jones] to the station on suspicion of being a "disorderly person" [translation: suspected prostitute illegally arrested without evidence] when he "saw a colored female and a colored male" walking down the sidewalk at John R. and Edmund. "The colored female I recognized as a known prostitute." The woman [Cynthia Scott] had money in her left hand. Spicher pulled over and searched the man [Charles Marshall] and found a knife. He then told the women she was under arrest "for investigation of larceny." The man became "belligerent" and said he "knew the girl, she was with him." [The unstated subtext here is that Marshall believed Spicher was accusing him of paying Scott in advance for prostitution]. While Patrolman Marshall restrained the man, Spicher started to put the woman in the squad car when "she turned around with a knife in her right hand and she slashed at me," cutting his finger. [Spicher sought treatment at Receiving Hospital for this alleged wound, which was one half of one centimenter long]. Then the "colored female" started running away. Spicher caught up with her, and "she kept slashing with the knife." He fired two shots, and "as she turned around, I fired a third shot." She fell to the ground with the knife still in her hand. (Spicher, notably, never says anything in any of his statements about Cynthia Scott slashing at his partner from the ground after the third shot).

Patrolman Robert Marshall stated that he "observed a known colored prostitute" with a wad of cash in her hand and asked Spicher to pull over to investigate. The man [Charles Marshall] became "indignant" and stated that Cynthia Scott was his girlfriend. Patrolman Marshall then searched the man while Spicher began to arrest "the girl." Then Spicher hollered out, "as if he was hurt," and began chasing the female, who was running away. Spicher caught up to her, and "she was swinging back and forth at him with the knife in her hand." She then continued to flee, and Spicher fired at her twice, and then "all of a sudden she slowed down and turned. He fired a third shot and she fell." Then, after Cynthia Scott was wounded and on the ground, Marshall claims that he "ran up to girl and as I attempted to take the knife from her hand, she swung with the knife at me, cutting my left sleeve," before he disarmed her.

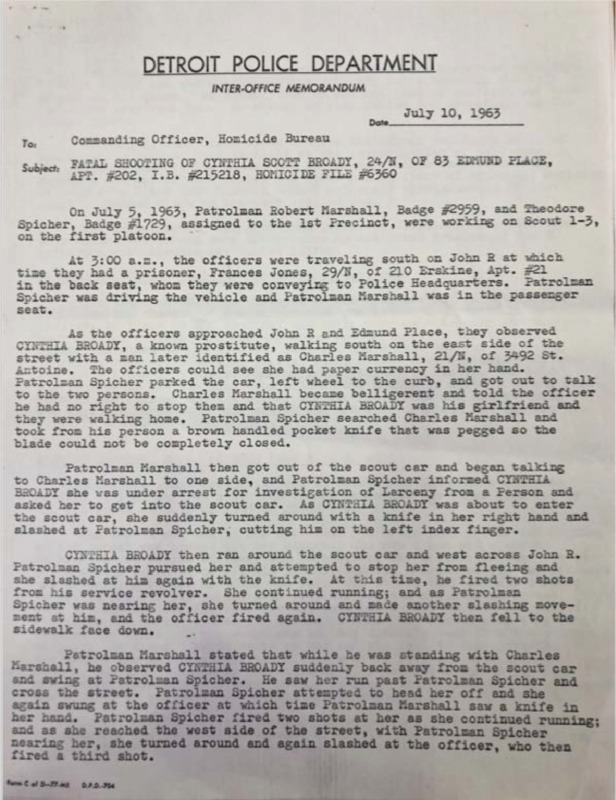

The DPD Homicide Bureau's initial investigative report (gallery, above right), filed July 10, presented the exact story as recounted by Spicher and Marshall as the objective and factual account of what happened in the encounter: Cynthia Scott resisted arrest, cut Patrolman Spicher with a knife, started to flee, and slashed at him again when he caught up to her. Spicher fired two shots as she was running away, and a third after she turned around, and she fell "face down." Then she also attacked Patrolman Marshall, while lying on the ground, before she died.

Did Cynthia Scott turn back around? The question of whether Cynthia Scott turned around before the third shot is contested. All of the eyewitnesses stated that the officer shot Cynthia Scott multiple times in the back while she was moving away from him and did not mention her turning around, and Rev. Campbell, who told his story to the Chronicle after release of the official account, specifically insisted that she had never turned back around. Officers Spicher and Robert Marshall, on the other hand, stated that the "known prostitute" did turn around to confront Spicher before the fatal shot, which could be interpreted as an extension of the cover story to portray her as the aggressor.

The Wayne County Medical Examiner report found that Cynthia Scott was legally drunk at the time of her death, with a blood alcohol content of .22, and that she had two bullet wounds. According to the coroner's report, one shot entered from the front, in the abdomen area, and exited the back. Another shot that entered her back pierced the heart and killed her immediately. This conflicts with Spicher's account that the final shot was the one that entered from the front. The coroner's report did provide support for Spicher's insistence that one shot entered from the front, although it is relevant that protesters also raised questions about whether the medical examiner was involved in a cover-up. After the fatal shot through her heart, according to Patrolman Marshall's statement and the DPD Homicide Bureau's attempt to make the cover story fit the facts, Cynthia Scott somehow managed to slash Marshall with the knife and cut his shirt before being subdued.

How did Cynthia Scott attack Officer Marshall after the fatal shot? The DPD Homicide Bureau's five-page report (above gallery) included a crucial detail, as recounted in Robert Marshall's initial statement (right), that is incompatible with Spicher's initial account and is not easily reconciled with the medical examiner's report. After Spicher fired the third shot, when all witnesses, initially including Spicher, said that the woman had fallen face down on the ground and appeared motionless, Patrolman Marshall allegedly "walked across the street and attempted to disarm Cynthia Broady and she slashed at him with the knife, cutting the left sleeve of his shirt. He finally had to put his foot on her hand and take the knife away from her" (see account above right).

The Smoking Gun in the Cover-Up

The most direct and compelling evidence of a smoking gun in the cover-up has been buried in the sealed archives of the Detroit Police Department until the 2020 release, under the Freedom of Information Act, of the Homicide Bureau's file on Cynthia Scott.

Patrolman Spicher's initial statement to the DPD Homicide Bureau, below left, is undated. The statement recounts the story of Cynthia Scott's alleged knife attack and concludes that after the final shot, she "then fell on sidewalk, face down." The revised statement, below right, is dated 5:00 a.m. on July 5, 1963. The second statement changes one crucial detail, eliminating the words "face down." In this version, Spicher "fired a third shot and she fell." (Our project added the red-line annotations highlighting this discrepancy).

The officers' tactical mistake in claiming that Cynthia Scott had slashed at both of them with the knife meant that Spicher had to adjust his testimony, with the apparent assistance of Homicide Bureau detectives, to reconcile how a dead woman lying "face down" had managed to cut Marshall's shirt with a knife. Spicher made the change in the rewritten, 5:00 a.m. statement so that his account was no longer directly contradicted by his partner's statement to the Homicide Bureau.

Recall from a previous section that eyewitness Robert Farr stated that one of the officers cut the other officer's shirt with a knife after the shooting, and he also stated that an officer took a knife out of Cynthia Scott's purse and cut his own hand. Witnesses Bernice Garland and Donald Johnson also described these cover-up efforts by the officers after the fatal shooting.

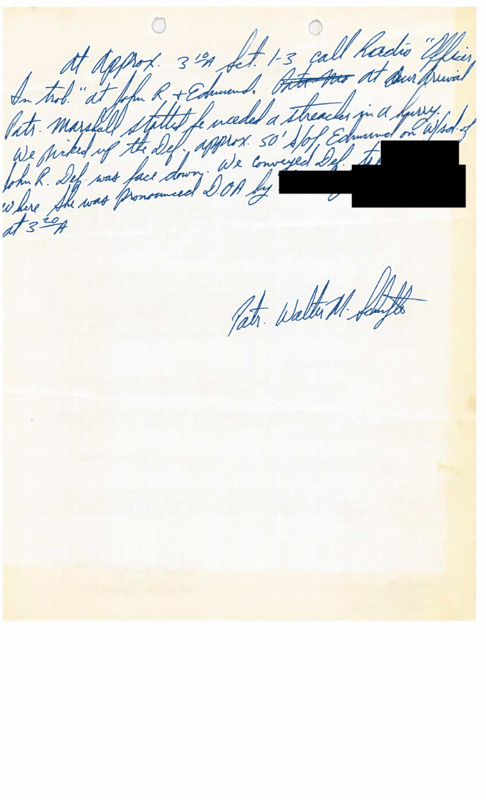

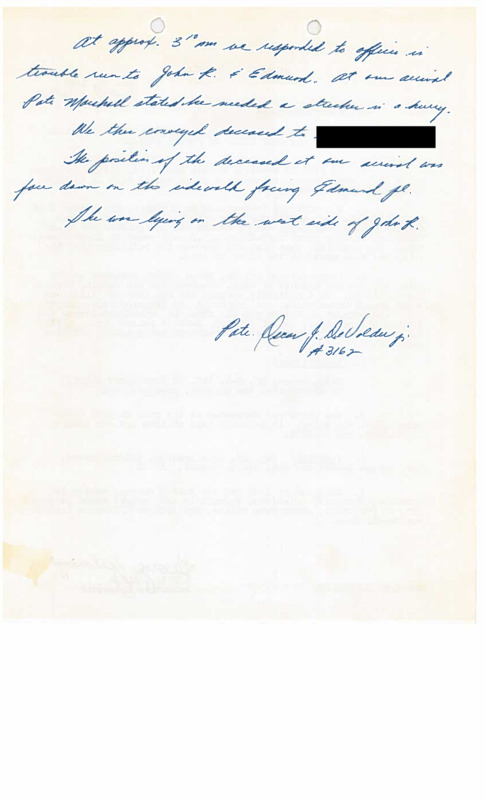

Two other police officers who responded to the scene after the shooting also submitted signed statements that the deceased woman was "face down" on the sidewalk when they arrived (see gallery below).

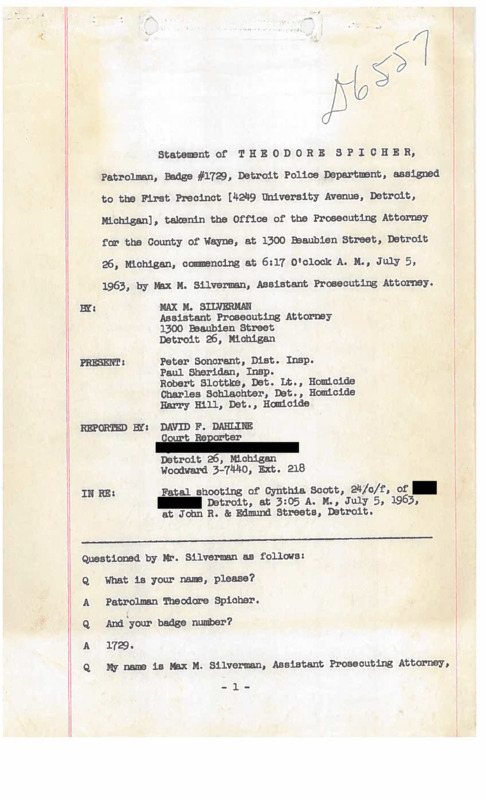

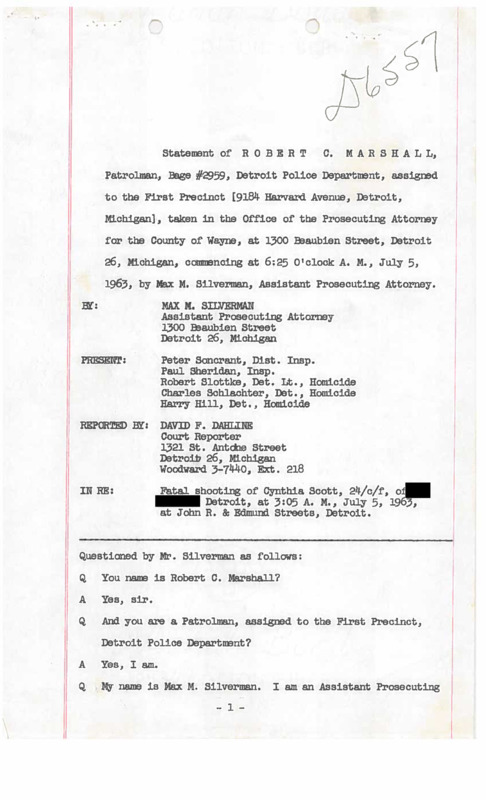

Patrolman Spicher and Patrolman Marshall gave statements to the assistant prosecutor, Max Silverman, in the early morning of July 5, about three hours after the shooting (gallery below). Silverman asked leading questions designed to help the officers reproduce the stories that they had given to the Homicide Bureau. He made no effort to ask any skeptical questions designed to seek the truth impartially, which was theoretically his job. Silverman did not ask Spicher about whether he had seen Cynthia Scott cut Robert Marshall after Spicher had shot her. He did not ask Spicher whether Cynthia Scott was lying "face down" on the sidewalk, as the eyewitnesses recounted and as the two police officers who responded to the scene also stated. He did not ask either officer to respond to the directly conflicting testimony from multiple African American witnesses, whom Silverman had questioned earlier that morning. Silverman did not even ask any probing questions designed to help the prosecutor's office make an independent assessment of whether the use of deadly force was justified under either Michigan law or DPD policy.

By contrast, Assistant Prosecutor Silverman asked the African American witnesses extensive questions seeking information that Cynthia Scott was armed with a knife and had attacked the officers, which all of them denied seeing. He asked them probing questions about their own criminal records and about whether they were inebriated that morning, seeking to undermine their reliability. The assistant prosecutor showed no interest in asking any follow-up questions when the African American witnesses implicated Spicher in felony murder and both officers in a cover-up (the prosecutor's examination of the civilians witnesses is in the final part of the full FOIA file).

The prosecutor's pro forma questioning of Theodore Spicher and Robert Marshall appeared designed to exonerate them. Readers are invited to decide for themselves through the gallery below.

Overwhelming evidence of a cover-up. The testimony of multiple eyewitnesses disputes the cover story told by the two officers involved, that Cynthia Scott attacked Patrolman Spicher and then ran, and continued to attack the officers after being shot, and instead unanimously agree that Spicher shot Cynthia Scott while she was walking away. Three eyewitnesses also state that one of the officers took a knife from Cynthia Scott, while she was lying motionless on the ground, and gave himself a superficial cut and then cut the other officer's shirt. (The witnesses do differ on which officer did what, which is not unexpected in a middle-of-the-night incident but provided the prosecutor's with a rationale to discount their testimony wholesale). The eyewitnesses gave these compatible accounts before the newspapers had printed the full stories of how Officers Spicher and Marshall described the encounter, and would not have been aware that the two officers had claimed that Cynthia Scott cut one on the finger and cut the other's shirt with her knife. No civilian witnesses, and not even Spicher's initial account, support the DPD Homicide Bureau's fabricated explanation for how Patrolman Marshall's shirt was cut by Cynthia Scott's knife while she was lying motionless, face down on the ground, presumably already dead.

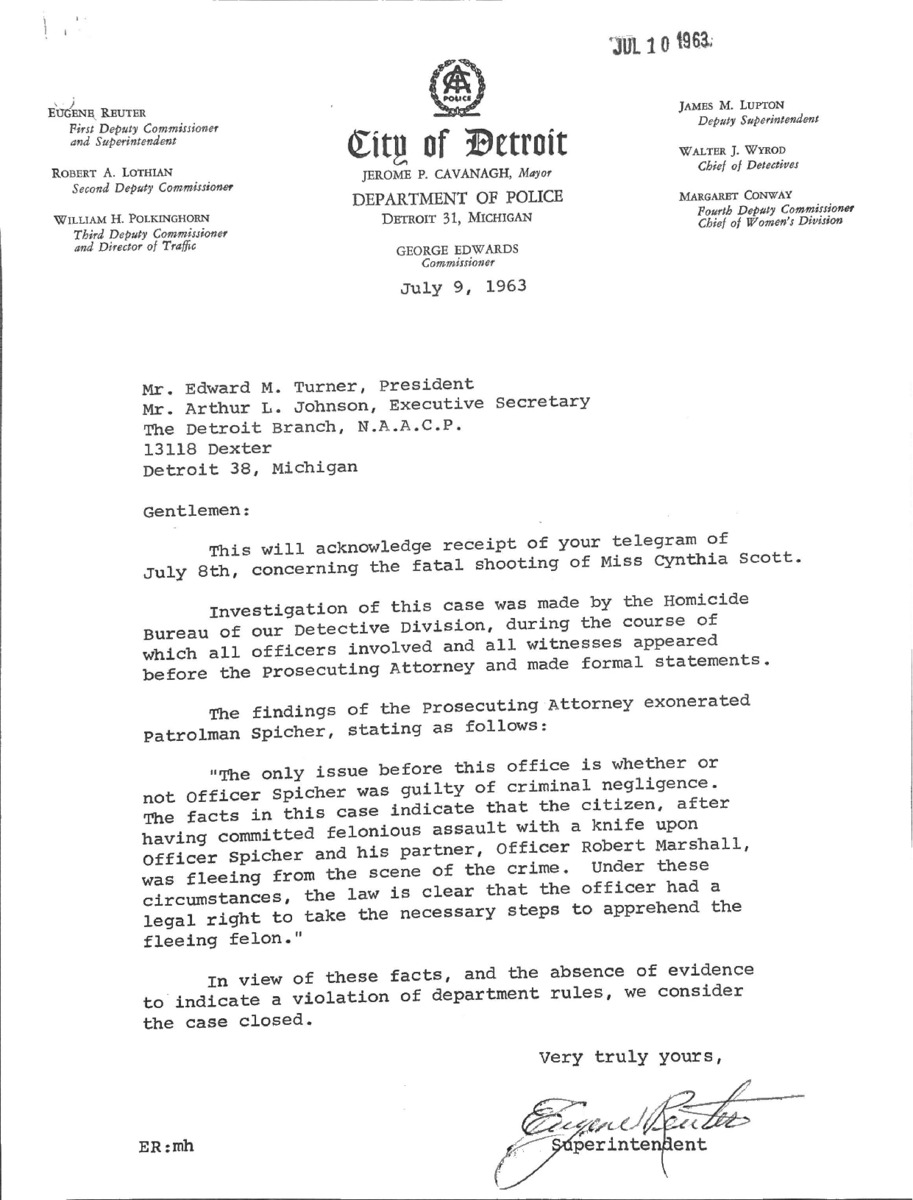

The Official Exoneration

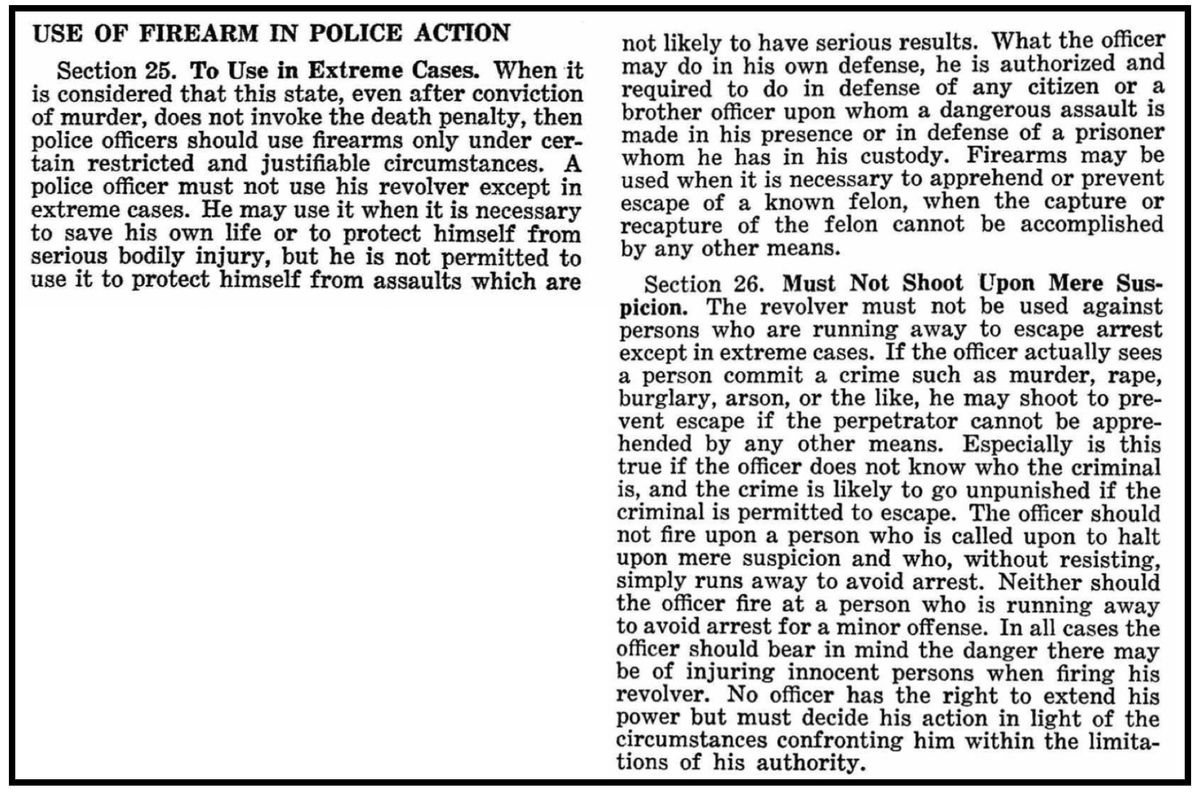

The Detroit Police Department hierarchy exonerated Patrolman Spicher based on the Homicide Bureau's investigation and declared that the case would be closed without convening an internal trial board to consider the discrepancies in the witness testimony or the overwhelming evidence that Spicher's decision to make an investigative arrest for a potential misdemeanor larceny offense was illegal and violated explicit DPD policy (right). Neither the DPD, nor the county prosecutor, appeared very concerned about whether Spicher's shooting of Cynthia Scott might have violated its own quite permissive use of firearms and deadly force policies, even if she did have a knife (bottom of page). These included:

- "A police officer must not use his revolver except in extreme cases"

- "He is not permitted to use it to protect himself from assaults which are not likely to have serious results"

- "Firearms may be used when it is necessary to apprehend or prevent escape of a known felon, when the capture or recapture of the felon cannot be accomplished by any other means"

- "The revolver must not be used against persons who are running away to escape arrest except in extreme cases"

- "The officer should not fire upon a person who is called upon to halt upon mere suspicion"

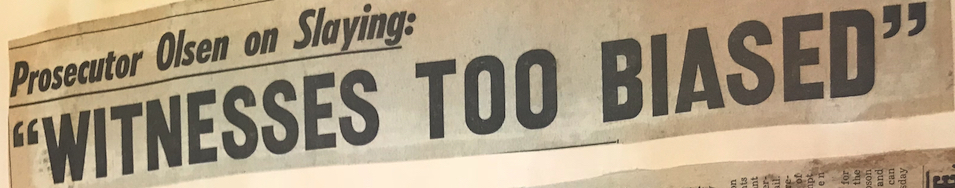

The Wayne County prosecutor's office conducted a cursory investigation, briefly interviewing the two police officers (above gallery) and much more critically questioning the civilian eyewitnesses who gave statements to the DPD Homicide Bureau. The prosecutor reached the same conclusion as the DPD, exonerating Theodore Spicher and declaring the killing a justifiable homicide. Prosecutor Samuel Olsen found the accounts of the police officers to be objectively true and told the media that the sworn statements of all of the African American witnesses were "too biased," presumably meaning because they were of the same race as Cynthia Scott. In Olsen's press release announcing his decision (below left), he did not even mention the existence of civilian testimony contradicting the officers' story, and the general public only found out about the competing versions after radical groups began protesting and the newspapers began more substantive investigations.

The Wayne County prosecutor's finding that Cynthia Scott had attacked Officer Spicher with a knife transformed her into a felon presumed guilty of assault with a deadly weapon. Under Michigan state law, the officer had the legal right to use deadly force against a "fleeing felon" (although even this prosecutorial interpretation was highly questionable, since DPD policy justified deadly force only when capture could not be accomplished "by any other means," and an inebriated woman walking slowly away with an address on file at the police department would not have been difficult to apprehend later). In announcing these findings, Olsen gratuitously disparaged the deceased Cynthia Scott as a dangerous criminal who displayed "utter and complete contempt for law and order."

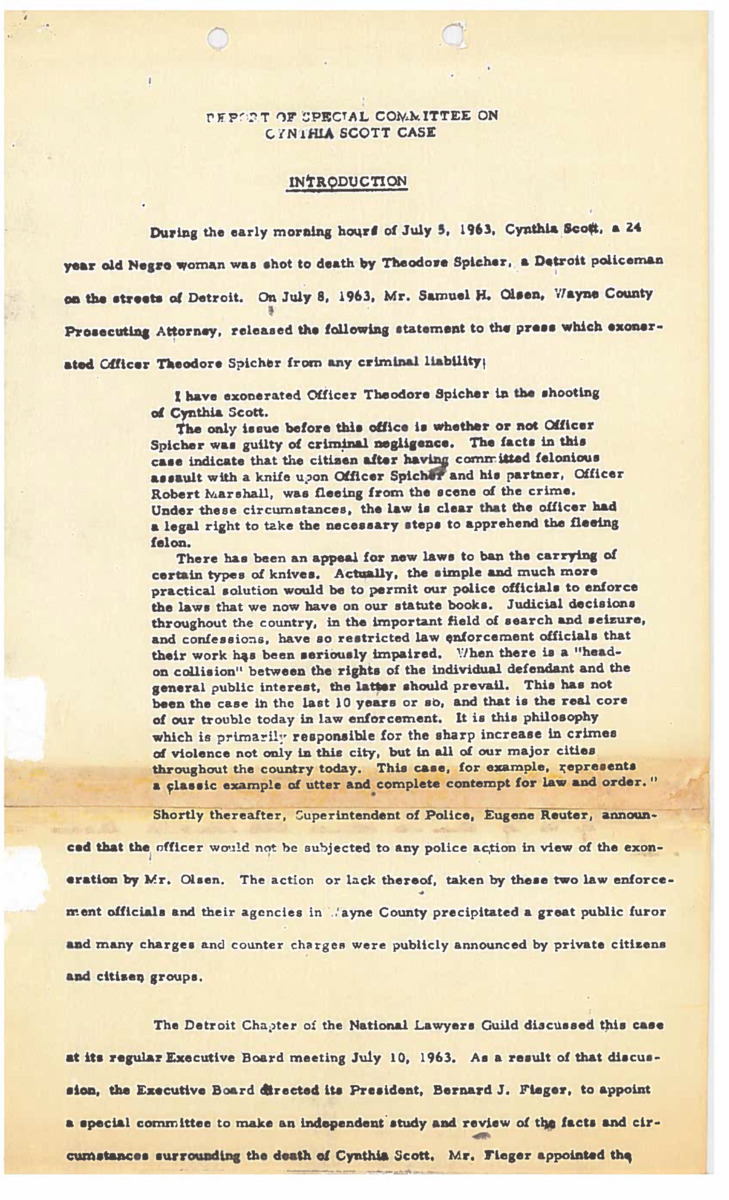

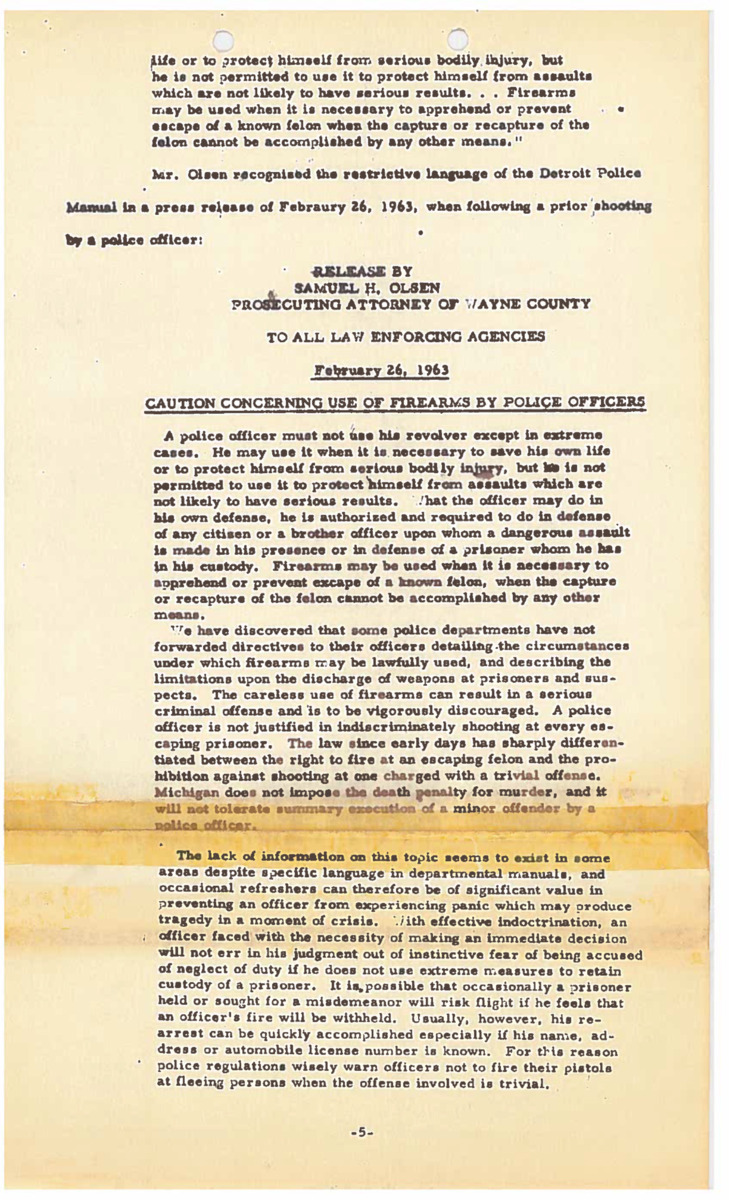

Many civil rights organizations accused the prosecutor of a cover-up, as the next page recounts in detail. The Detroit chapter of the National Lawyers Guild (NLG), a radical organization, formed a special committee to evaluate the prosecutor's decision in the Cynthia Scott case. In its report (below right), the NLG committee found that even if everything the police officers said was true (which the committee doubted), the attempted arrest of Cynthia Scott was illegal, as was the street search of her companion Charles Marshall. The report then labeled Olsen's justification of the officer's legal right to kill a 'fleeing felon' to be "one of the crudest perversions of law and fact" that the attorneys on the committee had ever seen. The NLG report concluded that the prosecutor's investigation was "careless, inadequate, and biased." Olsen's finding exonerating Spicher was "the product of either incompetence or a desire to obtain an exoneration from the very beginning. We believe the latter is the case, rather than the former."

The DPD Manual's "use of firearms" policy, revised in 1962, is below. Continue to the next page for civil rights protests against the Cynthia Scott murder and Spicher exoneration and additional fallout from this incident.

Sources:

Roy W. Stephens, "Prosecutor Olsen on Slaying: 'Witnesses Too Biased," Michigan Chronicle, July 13, 1963

Don Beck and Hal Cohen, "Cynthia Scott: 9 Versions of How She Died," Detroit Free Press, July 21, 1963

Detroit News Photograph Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

NAACP Detroit Branch Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

DPD Homicide Bureau, "Fatal Shooting of Cynthia Scott Broady," July 10, 1963, DPD Cynthia Scott File A20-02255 (FOIA file)

George C. Edwards, Jr., Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Joseph A. Labadie Special Collections, University of Michigan

Detroit Police Manual: Rules and Regulations of the Detroit Police Department (1962), Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library