Research Findings

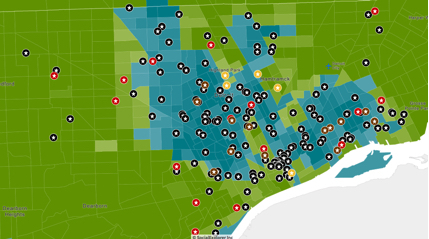

These are the overall research findings of the Fall 2018 HistoryLab class and subsequent Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab researchers that created Detroit Under Fire. Visit the exhibit sections for elaboration of all of these arguments, and consult the interactive series of maps for each section to visualize these findings as patterns in Detroit's racial geography.

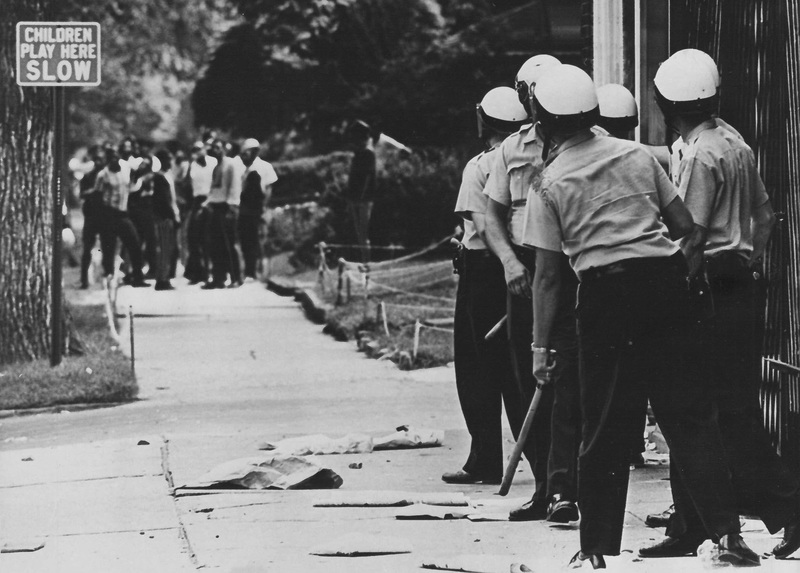

- Detroit Police Department (DPD) officers killed at least 220 civilians between 1957 and 1973, and this total is definitely an undercount. Around 79% were African American, 21% of the total were teenagers or preteens, and around two-thirds were unarmed and posed no threat when killed. More than one-third of the total were shot from the back while fleeing the scene of alleged property crimes. The evidence indicates that a significant number, around one-fourth of police homicides, were likely unprosecuted murders or unlawful manslaughter killings, even under the deliberately permissive fatal force guidelines. (This is not a legal determination of guilt but a research finding that the available evidence indicates that the cases should have resulted in a grand jury inquiry at the minimum). The DPD officially acknowledged 201 "justified" homicides by its on-duty officers, not counting the three Black teenagers killed in the Algiers Motel Incident for which white police officers were charged but acquitted. Our project has identified 151 of these on-duty homicides and an additional 18 by off-duty DPD officers, plus 19 more by other law enforcement agencies. Full details and analysis are on the Mapping Police Homicides in Detroit, 1957-1973 page of this overview section.

- The Wayne County Prosecutor, responsible for the city of Detroit, exonerated on-duty police officers in every homicide between 1957 and 1973 except for the three unarmed teenagers at the Algiers Motel during the 1967 Uprising, the killing of a licensed private guard, and a narcotics-related incident in 1973--all resulted in acquittals. DPD policy and state law gave police officers enormous discretion to use fatal force, even "to prevent the escape" of "suspects" who posed no threat to life. The police department deliberately liberalized the use "use of firearms in police action" policy after the 1967 Uprising, resulting in an exponential increase in police homicides. Many police homicides involved excessive force, including a significant number of where the evidence points to murder; the DPD Homicide Bureau and the Wayne County Prosecutor covered up or whitewashed almost all of them.

- The Detroit Police Department enforced racial segregation and policed the color line through policies of racial criminalization and racialized violence, rather than focusing on solving crimes in Black neighborhoods and protecting all citizens.

- Police brutality toward African Americans was systemic, not a problem of a few individual "bad apples," as policymakers and DPD leaders designed citizen complaint and internal investigation procedures to maintain police discretion and insulate officers from discipline even in egregious cases of clear felony assault and murder of civilians. The point is not that all police officers were brutal and engaged in criminal behavior, but that the DPD as an institution and almost all police officers as individuals covered up the brutality and criminal violence of a significant number of officers, a process known as the "Blue Curtain." (Each chronological section of the exhibit includes a map documenting all identified incidents of police brutality and misconduct for that time period).

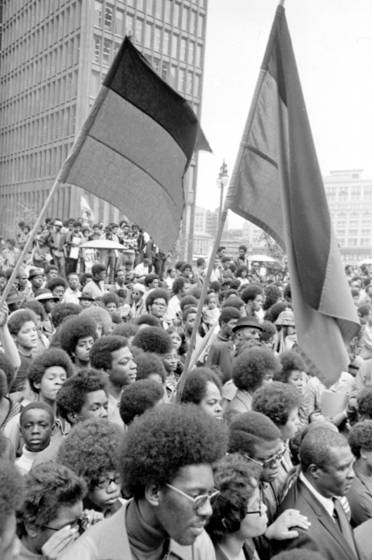

- The history of police violence and discrimination against Black citizens of Detroit during the civil rights era reveals that the racist law enforcement in the cities of the urban North was not that different from the better known history of white supremacy and segregationist violence in the Jim Crow South. The anti-police brutality movement in Detroit was a sustained political mobilization by a broad spectrum of civil rights organizations and community activists throughout this era, from the late 1950s through the early 1970s.

- Civil rights activists pushed unsuccessfully from the late 1950s onward for a civilian review board to conduct independent investigations of police brutality and misconduct, which the DPD adamantly opposed, as did prominent white liberals such as Mayor Jerome Cavanagh.

- The majority of the white public in Detroit opposed civilian oversight of the DPD and endorsed both racial segregation and "tough" police crackdowns against African American citizens perceived as criminals and against Black neighborhoods collectively, as indicated by support for mayoral candidates and evidence from letters to political officials.

- Liberal reforms in the mid-1960s addressed issues such as discourtesy and racial epithets through ineffective psychological training. Such efforts deliberately did not address systematic police misconduct because liberal policing in the war on crime depended on policies of criminalization of Black civilians and neighborhoods by maintaining police discretion on the street and through stop-and-frisk procedures of racial profiling.

- Liberal reformers and mainstream civil rights groups also sought to improve "police-community relations" by diversifying the police force, which was almost completely segregated until the mid-1960s and remained more than 90% white into the early 1970s. The DPD and the Detroit Police Officers Association union resisted efforts to address racial discrimination in employment policies, and African American officers faced extreme prejudice and discrimination from their white counterparts.

- The DPD, under a liberal regime (city and national), militarized policing in the mid-1960s in response not only to street crime and "riots" but also to criminalize political activism and mass protests by civil rights and black power organizations.

- After the 1967 Uprising, the DPD embraced open and violent political repression of civil rights, black power, and white New Left activists--including explicit politically motivated violence against nonviolent protesters and in preemptive strikes against black power groups.

- Black power and white radical activists in the late 1960s and early 1970s moved beyond the call for a civilian review board toward a vision of total civilian oversight and Black community control of the police department. Mass protests against the DPD were common during the Black community mobilization of this era.

- The DPD criminalized and illegally surveilled political activists and civil rights, black power, and other left/radical organizations on a mass scale. The department used discretionary procedures to harass civil rights and left activists, including criminalizing protests against police harassment and brutality.

- The DPD operated as a right-wing political organization in local politics, especially through the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA) union, which became a significant independent political force in the mid-to-late 1960s. The department could not be controlled by the mayor by the late 1960s.

- The DPD contained extensive networks of corrupt police officers in its ranks, especially in the drug and sex markets. The exposure of the Pingree Street Conspiracy in 1973 revealed the depth of police narcotics corruption in one precinct but was also only the tip of the iceberg.

- DPD violence against women was most notably against young political activists, mothers who filed complaints of brutality on behalf of their family members, and sex workers. The 1963 police murder of sex worker Cynthia Scott, and the prosecutorial coverup, was a turning point in Detroit's civil rights movement and expanded the anti-police brutality campaign beyond the middle-class oriented NAACP and ACLU into a grassroots protest movement by black power organizations.

- The DPD punished very few officers for any acts of brutality or misconduct during this time period, and routinely found civilian complaints to be unjustified or lacking in evidence, indicating a system designed to insulate these actions from oversight. No police officer was fired for on-duty brutality against a civilian during the 1960s. (See each section's page on patterns of police brutality and misconduct for elaboration).

- Most instances of police brutality and the identities of many of the people killed by DPD officers are not available in the archives because of deliberate silencing.

- The Wayne County Prosecutor, responsible for deciding whether or not to bring charges in the event of a police killing and other allegations of police violence, routinely exonerated officers and covered up misconduct and even murder, and therefore shares significant responsibility for the racial injustices and civilian fatalities of the DPD during this period. (See each section for the central role played by the county prosecutor in insulating police officers from accountability throughout this time period).

- The Detroit Police Department during this era operated as an extension of Detroit's criminal justice and political systems rather than as an outlier. Mayoral administrations (conservative and liberal), county prosecutors, local courts, the county jail, the cash-bail system of pretrial detention, and other public officials and agencies all contributed to the systemic patterns of police violence and misconduct.

- The DPD was the most deadly police department per capita in the nation between 1967-1973, the era of the Detroit Uprising and the notorious STRESS operation, leading to a mass movement against police violence and brutality that culminated in the election of an African American mayor in 1973.