Adult Community Movement for Equality

Throughout the mid-1960s, it became evident that significant strides were not being made to improve the lives of African American citizens in Detroit, or nationally, especially in relation to the persistent occurrence of racially targeted police brutality. Additionally, tensions within the African American community between members of the middle class and working class began to rise. Organizations such as the NAACP and the Detroit Urban League (DUL) remained liberal civil rights groups that placed an emphasis on working and negotiating with white liberal and establishment leaders such as Mayor Cavanagh and Police Commissioner Ray Girardin. Through this partnership, they hoped to find solutions for racial inequities across all sectors of life in Detroit including education, employment, housing, and police-community relations. However, unsatisfied with the traditional civil rights organizations, many new civil rights groups developed with more radical approaches to create the much needed change. One such group that formed on the East Side of Detroit was the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME).

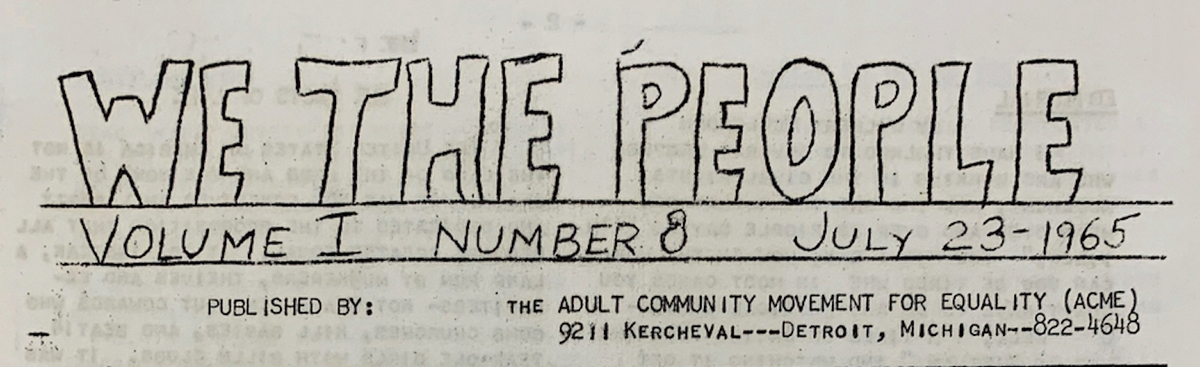

In 1961, Peter Countryman founded the Northern Student Movement (NSM) at Yale University to support the sit-in movement conducted in the South by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The founding students, including Countryman, were all white activists. Influenced by SNCC, NSM sought to fight racial discrimination in the North. In its early years, NSM focused on providing tutorial programs in northern cities with large, oppressed African American populations such as Philadelphia, Chicago, New York City (Harlem), and Detroit. The Detroit program began in June 1962 as the NSM Detroit Education Project, a tutorial program focused on providing educational help to the city’s poor. Additionally, the NSM Detroit branch founded a non-tutorial program, the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME). ACME quickly emerged as a powerful group focused on bringing together the voices of Detroit’s African American majority. In a 1964 fundraising letter, NSM outlined its beliefs as a grassroots organization with goals of making change rooted in community efforts and desires.

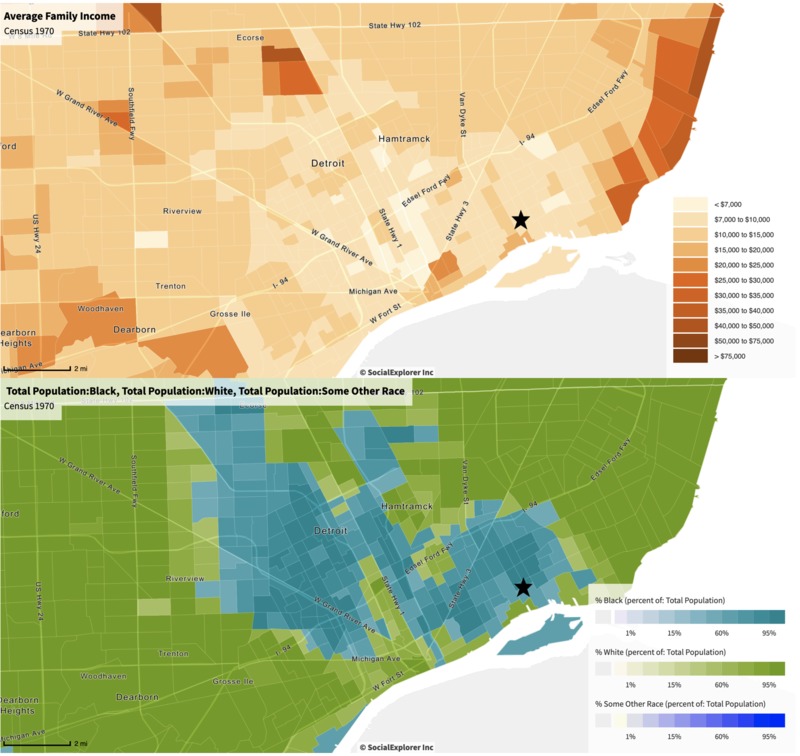

With these beliefs in mind, ACME organized on the East Side of Detroit and located its headquarters in a neighborhood with a high concentration of poverty and a mostly African American population (see maps to the left). The organization’s membership included mothers on welfare, factory workers, unemployed men and women, housewives, and youths. In Detroit, NSM and ACME focused on creating a movement that focused on significant change and the needs of low-income African Americans living in the “ghetto.”

The maps on the left show the location of ACME headquarters at 9211 Kercheval on the East Side of Detroit on a income and a race map. Nancy Milio described the office after a 1966 meeting with Alvin Harrison: “The ACME storefront served as communications center, meeting place, training ground, and limited living quarters. It had two desks, a gas burner, a dozen folding chairs, some makeshift bookshelves, and stacks of mimeographed speeches and pamphlets. Its plasterboard walls were covered with city maps, pictures and words of Malcolm X, and news clippings of police incidents."

Frank Joyce, a young white radical and native Detroiter who directed ACME, emphasized its focus on addressing the institutionalized powerlessness of African Americans in the urban North. Another key leader, Alvin Harrison, was an African American member of NSM and later the chairman of ACME and its youth branch, the Afro-American Youth Movement (AAYM). Both men believed that the group could give a voice to lower-income African Americans at a time when liberals were focused on the demands of the middle and upper class.

As Joyce stated, "The basic question is who controls black people’s lives?".

In the beginning, ACME set out to give African Americans control by combatting discrimination in housing, employment, education, and other areas where deep systemic inequalities existed. However, they became increasingly motivated to fight police brutality as incidents became more frequent and ACME became a target of local police because of its civil rights activism.

Frank Joyce Interview (May 2, 2019). Click to watch a 5 minute excerpt from the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab's interview with former ACME director Frank Joyce, in which he discusses his discovery of NSM and the founding of ACME in Detroit.

Police Surveillance and Harrassment of ACME

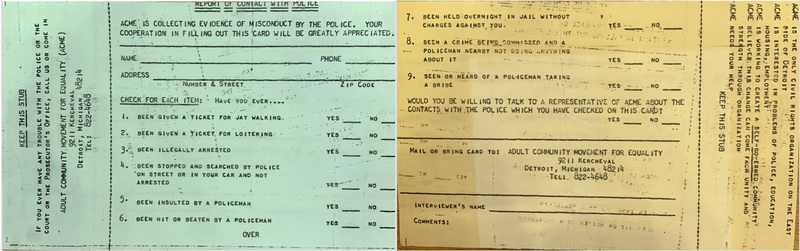

Police surveillance of ACME quickly began as the group organized members of the East Side community to fight for racial equality in Detroit. ACME leaders first asked community members what they viewed to be the most pressing problems. The group sent out questionnaires inquiring about housing, public and private schools, hospitals, police brutality, discrimination, and government retraining programs (see flyer above). In addition to the many community members who believed police brutality to be a high-priority issue, the frequent harrassment, misconduct, and brutality experienced by ACME members at the hands of the police caused the organization to shift its focus to primarily protest police brutality, in addition to the other major issues the group was founded on combatting.

The 5th and 7th police precincts were mainly responsible for the harassment experienced by ACME and the surrounding African American community. Encounters with officers from the two nearby precincts frequently ended in the arrest of citizens with no lawful reason (also see map below). Additionally, ACME members noted that in many of the incidents with police, they recognized the police officers and knew that the officers recognized them as ACME affiliates. The fact that many of the encounters that led to arrest happened around ACME headquarters led members to believe that they were likely under surveillance and the police viewed them as a threat. In fact, Nancy Milio, a white nurse who operated a nearby Mom and Tots center on Kercheval, confirmed in her 1970 book 9226 Kercheval, that officers used the top floor of the center to monitor the ACME storefront and member activity during the 1966 Kercheval Incident. Milio wrote, "Her son [the son of one of the clinic workers] had given the keys of the second-floor clinic to men in police uniforms and plain clothes. They returned the keys after making duplicates. They watched the AAYM storefront at night through the clinic windows." This admission, which Milio says she did not know about until after the fact, confirms the surveillance of ACME, and AAYM, by the DPD, and how they used another community organization to do so.

Additionally, discretionary policing laws greatly affected members of ACME, and the largest number of loitering tickets were issued by the 5th Precinct, which frequently patrolled the area surrounding the group's headquarters. Moses Wedlow, an ACME activist, unsuccessfully challenged the anti-loitering law as unconstitutional, and a pretext for illegal police searches and harassment, after one such ticket in June 1965. Many ACME members reported being followed by police cars upon leaving the headquarters and arrested unlawfully, such as the case of Alex Shimpkin, who was arrested for not having a Michigan driver’s license even though he showed the officer who pulled him over a valid Illinois license. Another example of targeted police harassment against ACME was the arrest of 43 people attending a private party at the house of Mr. and Mrs. Lobert Matthews, ACME members, under the false claim made by police officers that it was a blind pig (illegal liquor joint).

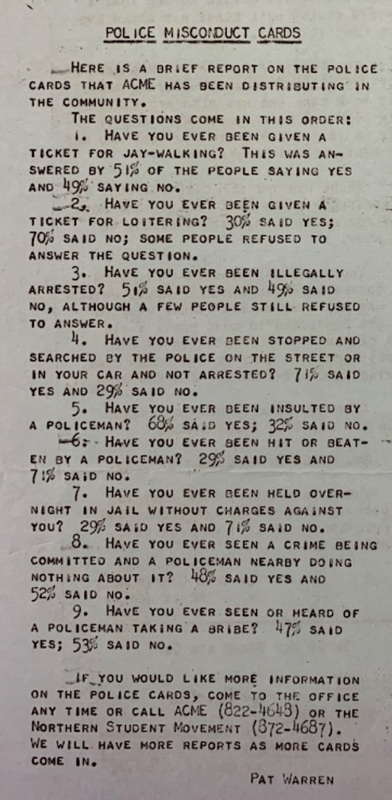

Continued harassment and surveillance of ACME by the police, in addition to complaints of community members, encouraged ACME to shift its main focus to combat discrimination and brutality against African Americans by the DPD. On July 1, 1965, ACME published results from the police misconduct cards, distributed throughout the community to learn more about the experiences of citizens in the area, in its biweekly publication We the People. ACME found that a majority of respondents had experienced police misconduct in the form of unnecessary or illegal arrests, ticketing, verbal insults, etc. (The We the People report of this survey and the distributed police misconduct cards can be viewed on the right).

As the group continued working on the East Side of Detroit, it became more and more apparent that police brutality and misconduct were the most important issues to tackle in the “ghetto,” and ACME replaced its original goal of educational tutorials. Additionally, during this time ACME emphasized the widespread police brutality that was hidden or “whitewashed” in the popular white media, and compared the problem to that in the southern Jim Crow states. There were many occasions where members witnessed or experienced brutality at the hands of the police in addition to the frequent occurrence of harassment.

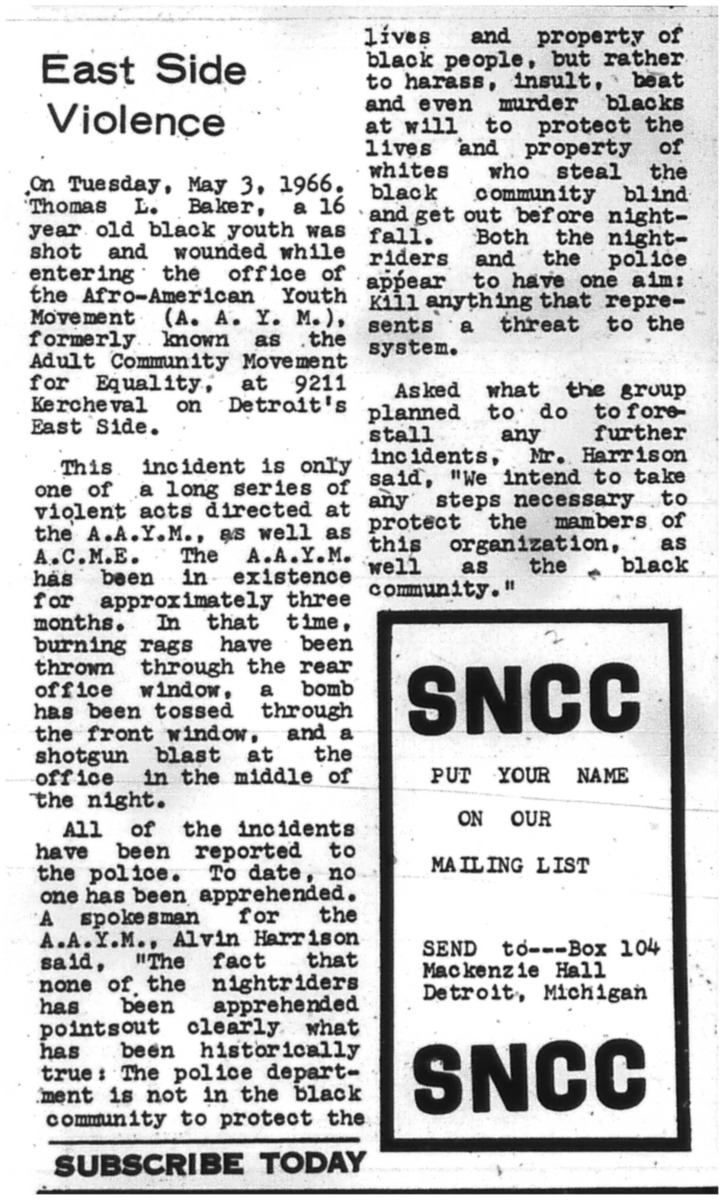

However, the DPD was not the only force that targeted ACME and its members. There were many instances where the group experienced harassment and threats from white residents of nearby neighborhoods, mostly during the night time. The window of headquarters was frequently shattered as a result of bombs, flaming rags, bullets, etc., being thrown at the office to threaten the radical organization. One edition of We The People even had a section dedicated to announcing the new window which was installed on August 16, 1965, that "would be protected from future assaults by a wood covering which is put up at night."

Frank Joyce Interview (May 2, 2019). Click to watch a 9 minute excerpt from the Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab's interview with former ACME director Frank Joyce, in which he discusses the tensions between community organizations and the DPD, and recalls a few specific interactions between himself, other ACME members and the police.

Mapping ACME/AAYM Protests and Police Harassment, 1964-1966

- Black dots = ACME/AAYM protests against the Detroit Police Department

- Red dots = Police harassment of ACME/AAYM members (including false arrests, arrests for nonviolent protests, traffic and loitering tickets as punishment for constitutionally protected political activities)

- Yellow dots = Police brutality against ACME/AAYM members

- Note: Zoom for the incidents clustered around ACME headquarters and police precincts. Blue = black neighborhoods (1970 census map).

This map of Detroit's racial geography (1970 census) displays 37 incidents involving ACME, and in a few cases its predecessor organization the Northern Student Movement and its successor organization the Afro-American Youth Movement, between 1964 and 1966. It provides evidence of the broad scope of ACME's protests against the Detroit Police Department, and of the punitive police response that criminalized ACME leaders and members for the exercise of constitutionally protected rights to free speech and assembly. Many of the incidents are clustered around ACME's headquarters at 9211 Kercheval Ave. on the East Side of Detroit, and around the locations of the 5th and 7th police precincts (zoom to view tightly clustered incidents). Collectively they provide powerful evidence that the police department in a northern city harassed and punished nonviolent civil rights activists for the exercise of their constitutional rights, similar to the more familiar story in the Jim Crow South.

The cluster of incidents on the West Side of Detroit involves weeks of ACME picketing of Azzam's Market at 5985 14th St. during the spring of 1965, after Jacob Azzam (son of the store owner) shot and killed 20-year-old John Christian, an African American, in a dispute that began when an unidenitified boy allegedly stole a cake. Azzam claimed that John Christian threatened him with a knife, and the Wayne County prosecutor's office ruled the shooting a justifiable homicide. When ACME organized pickets to protest the refusal to charge Jacob Azzam, prosecutor Samuel Olson charged more than 30 protesters with a conspiracy to run the Azzam's out of business through "illegal picketing." This punitive action by the Wayne County prosecutor eventually forced ACME to agree to discontinue the daily pickets.

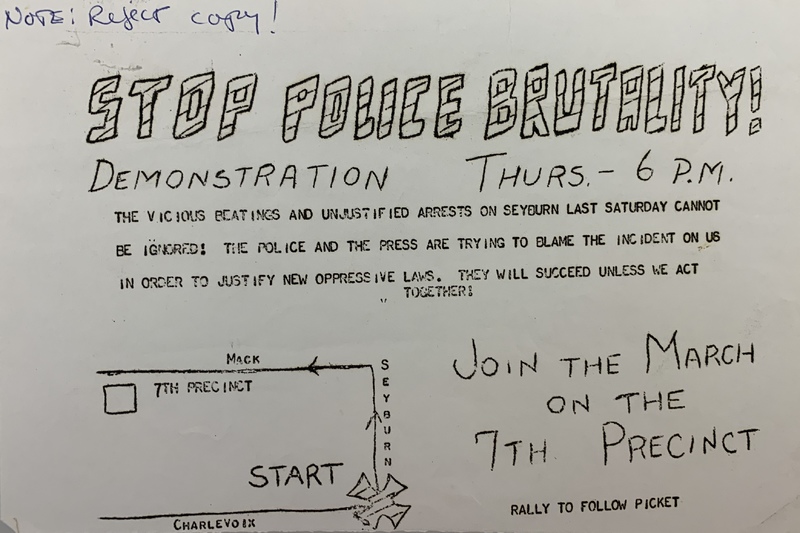

Throughout the mid-1960s, ACME conducted many rallies, demonstrations, and pickets against not only police brutality but also against white store owners, housing segregation, and other racially discriminatory practices. ACME distributed used flyers, such as this one for the Seyburn Incident protest, to encourage people in the community to attend and to build a grassroots direct action civil rights movement in the urban North. Through public protest, ACME sought to give all community members a voice, whether or not they were members of the organization. ACME utilized the grassroots organizing style as the main strategy in its fight against racial discrimination, rather than the NAACP and Urban League approach of meetings and formal relationships with Detroit’s white leaders. ACME wanted to be heard from the streets. The title of their newsletter “We the People,” showed this determination to provide a voice to those in the African American community who had not been heard.

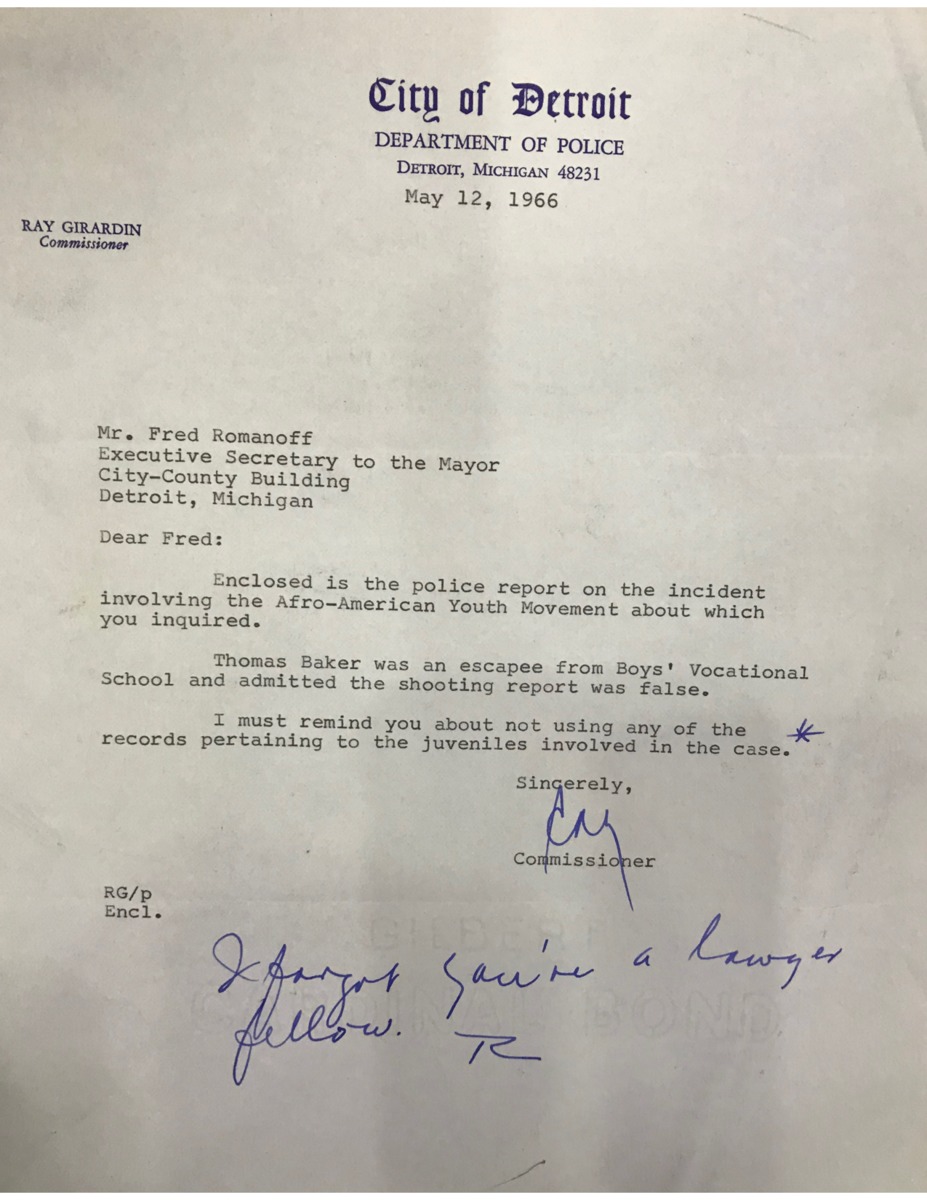

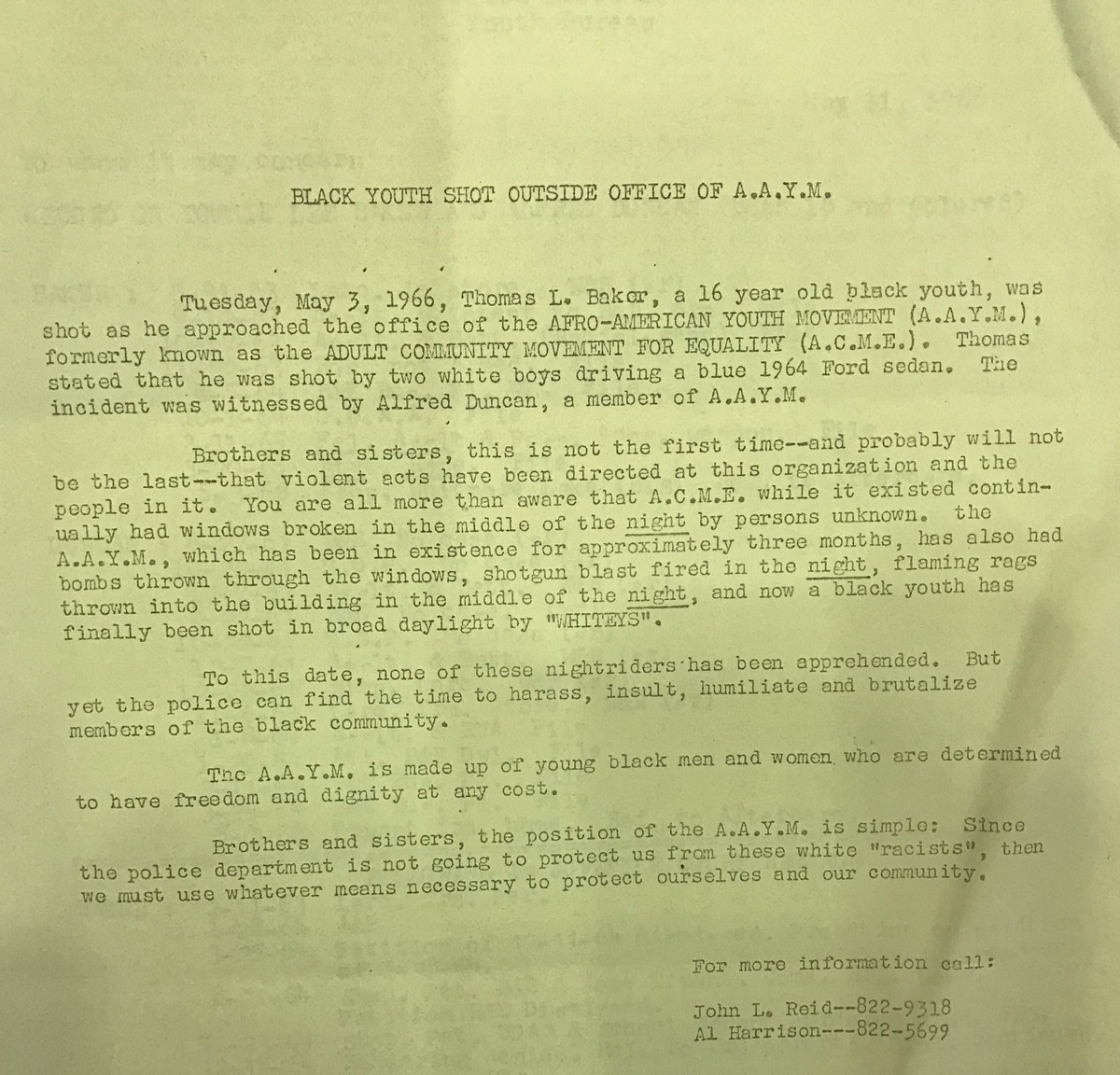

The DPD and the Thomas Baker Shooting

Thomas Baker, a 16-year-old African American male, was shot on Tuesday, May 3, 1966, outside of the Afro-American Youth Movement headquarters at 9211 Kercheval Avenue. The bullet came from a car window. Inside the car were two white boys who called out “Hey” to Baker before firing one shot and speeding away. Baker was taken to Detroit General Hospital with a bullet wound near the left collar bone. In response to the shooting, the police claimed that Baker changed his story to hide the fact that he was shot by someone from inside the ACME office. In the DPD investigation, which can be explored in the gallery below, it is clear that the detectives made little attempt to track down the shooter. Instead, it appears that they continually questioned the listed witnesses, Alfred Duncan and Tom Reid, as well as Baker, to find proof for their assumption that Baker was shot from within ACME headquarters. A significant portion of the DPD’s efforts went into finding evidence to support their unfounded claim that Baker had filed a false complaint, including swabbing both witnesses’ hands for nitrate, and describing the criminal records of Baker and others involved.

This incident was representative of the harassment ACME, and later AAYM, experienced from the white community, specifically the police in Detroit. Additionally, this shooting occurred around the same time that Stokley Carmichael was elected as chairman of SNCC and began to call for Black Power. The Thomas Baker event marked a shift in ACME’s response to incidents of harassment and approach to handling interactions with the police. Following Baker’s shooting, the AAYM flyers and newsletters took a more powerful stand against the police and white racism. They stated “Brothers and sisters, the position of AAYM is simple: Since the police department is not going to protect us from these white “racists,” then we must use whatever means necessary to protect ourselves and our community.”

The Seyburn Incident

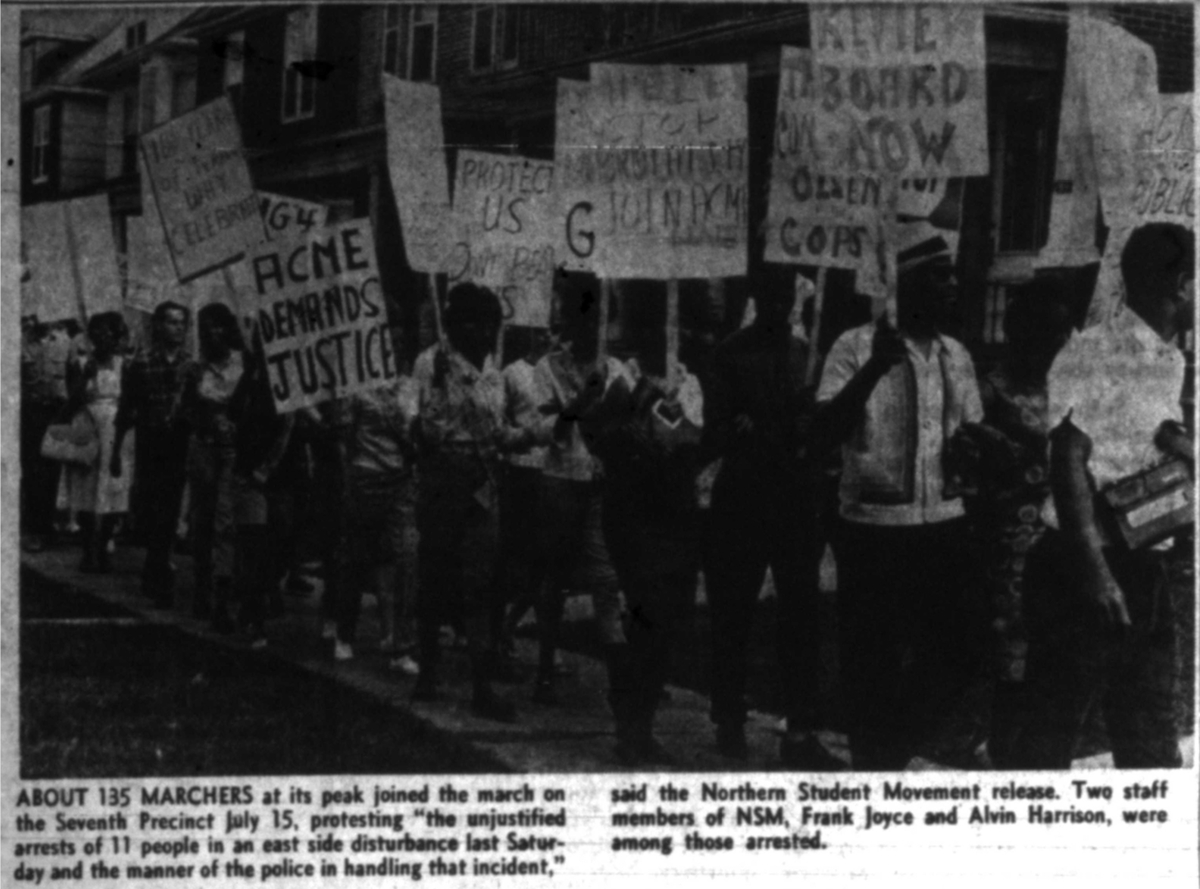

On July 10, 1965, officers from the 7th Precinct made eleven arrests, including a group of ACME members on Seyburn Street between Charlevoix and Goethe. According to the NSM publication The Organizer, “The disturbances began at 11:15 with the issuance of a traffic ticket to 19 year old John Mumford for making a wrong turn. Not content to issue the ticket peaceably, the policeman started to beat Mumford and when John Scott, who was also in the car, intervened, he was beaten as well.” A large crowd gathered around, which prompted a rookie officer to call for assistance.

ACME’s involvement began when five members, Frank Joyce, Alvin Harrison, Cortland Cox, Martha Kocel, and Dorothy Dewberry, were driving from the headquarters at 9211 Kercheval to a member’s house. While driving, they saw several speeding police cars with flashing sirens head toward a nearby neighborhood and stop. Joyce, Harrison, and Cox went to investigate the scene, while Kocel and Dewberry remained in the car a few blocks away. At the scene, they counted 15 police cars, including one with a broken window as a result of two bricks thrown. They also witnessed approximately six officers, some not in uniform, chase a man, Mr. Dennis, onto a porch and throw him down the steps. Once on the ground, Mr. Dennis was kicked, clubbed, and handcuffed for resisting and obstructing the duty of a police officer.

The police ordered Joyce, Harrison, Cox, and the rest of the crowd to disperse from the scene. The three ACME members were followed by a 7th Precinct officer to the corner as they stopped to wait for Kocel and Dewberry to join them. While there, the officer told Joyce that he was obstructing the sidewalk and to move. The Organizer reported that “when he [Joyce] moved from the sidewalk to the grass, the policeman ordered him into the police car. Cortland Cox asked the officer if he could go down the street to meet the girls they were waiting for, in reply to which he was ordered into the car. Alvin Harrison was looking for a telephone and was told by the officer that he was obstructing traffic and to get in the car.” All three were charged with resisting arrest and obstructing an officer in the course of duty.

In addition, the incident is typical of the mainstream white media response to police brutality and misconduct of the time. Popular news sources such as the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News, published stories that described the incident as a police “brawl” and reported the injuries of police officers and the presence of a large mob. Headlines from such articles can be viewed below. Not one media source mentioned the police beating of African Americans, but rather they all spun the story to criminalize civil rights activists and the black population of the East Side, and to invoke fear in white readers. A WJBK TV and radio broadcast on July 13, 1965, stated that the arrests occurred “after a wild struggle in which a couple of hundred pushing, shoving, brick-throwing rioters mauled a Detroit police squad,” and added that “a dozen police cars were involved, and several policemen had been kicked, struck and beaten.” The broadcast continued to warn listeners of the ensuing danger that came from “defiance of law” and encouraged the Detroit community to take action. (The full broadcast can be read in the document to the left).

ACME criticized the media reporting of the incident in the Michigan Chronicle and in their organization newsletter. Al Harrison, one of the arrested ACME members, wrote an article in We the People, seen on the right, titled “Mob Action . . . So Called.” Harrison explained the brutality and disrespect exhibited by the police on Seyburn Street, explicitly stated that the event was not a riot, and challenged the media and political leaders to do better. He wrote, “I challenge the news media to produce the names of witnesses to this 'mob action' other than the police.” Harrison also challenged Commissioner Girardin, Mayor Cavanaugh and the Common Council to give the citizens involved in the Seyburn incident the opportunity to speak at a public hearing. Frank Joyce, also arrested at the scene, was quoted in the Michigan Chronicle following the incident denying that a riot took place. Joyce said, “the aggressive and abusive manner of the police officers served only to antagonize the people present, and it is important for the public to understand that a riot did not occur that evening only because the community people did not respond with violence to the brutality of the police involved.” Additionally, ACME organized a march from the scene of the Seyburn Incident to the 7th Precinct and picketed the station. This protest was similar to many others organized and supported by ACME and NSM in the mid-1960s, as show in the map below.

Sources:

Detroit Commission on Community Relations / Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Fifth Estate

Frank Joyce Interview, May 2, 2019, Grosse Pointe Park, MI, by Matthew Lassiter, Jesse Blumberg, and Jack Mahon, https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_n2916388/145739741

Frank Joyce Oral History by William Winkel, 4/21/2017, Detroit Historical Society, https://detroit1967.detroithistorical.org/items/show/497

Jerome P. Cavanagh Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Michigan Chronicle

Nancy Milio, 9226 Kercheval (1970)

Northern Student Movement Records, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

ProQuest History Vault

Stanford King Institute