Diversity and Public Relations

In the late 1960s, the Detroit Police Department resisted almost all civil rights demands for reform and instead invested in a public relations campaign designed to change its reputation among the city's black residents through marketing rather than actual policy shifts or meaningful investigations of brutality and misconduct. The only civil rights demand that the DPD publicly embraced was the need to hire more African American officers to police a city whose black population exceeded 40% by the late 1960s. The DPD and the Cavanagh administration recognized that the public legitimacy of the police department depended on changing its reputation as a bastion of white working-class officers who often terrorized black neighborhoods. They denied that police brutality actually existed but did acknowledge the public relations challenge in African American neighborhoods that deeply mistrusted the police. Police professionalization reformers also argued that effective crime control was undermined when the law-abiding majority in the black community distrusted and therefore was disinclined to cooperate with the police department.

White liberals, the mainstream civil rights groups, and police professionalization advocates inside the DPD all believed that having more African American officers on the streets would transform police-community relations. This view was overly optimistic, because it failed to recognize or acknowledge that community distrust resulted from broader DPD policies of militarization and over-criminalization, discretionary stop-and-frisk policing through racial profiling, targeted and selective law enforcement in poor black neighborhoods, and complete failure to investigate and discipline officers for brutality and misconduct. But even if a huge influx of African American officers would have made a difference, the DPD hierarchy undermined the city's efforts to diversify the force by keeping its racially discriminatory employment practices in place and insisting that only "qualified men" would be hired and promoted through its allegedly color-blind and merit-based process. Despite its public commitment to diversification, the DPD continued to reject black applicants at much higher rates than comparable white applicants during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The percentage of African American officers did slowly increase during this period, but substantial diversification did not happen until the election of an African American mayor in 1973 and the subsequent implementation of a robust affirmative action program.

Pressure for Affirmative Action

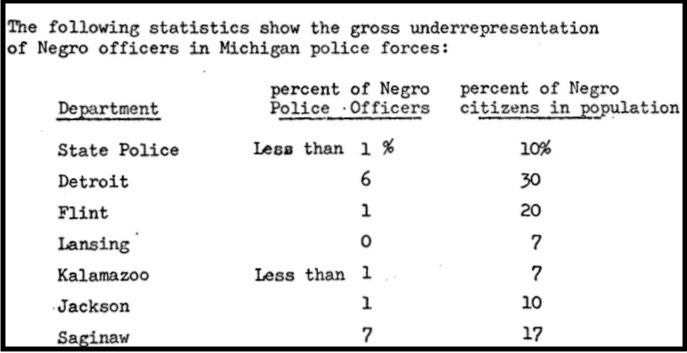

Civil rights groups, led by the Urban League and the NAACP, had been pressuring the Detroit Police Department to hire more African American officers since before World War II. In the late 1950s, the Urban League labeled the DPD a segregationist organization, and a coalition of civil rights groups launched a concerted effort to pressure the department to hire and promote more black police officers (at this time meaning exclusively black men). This campaign continued in the early-to-mid 1960s, but DPD resistance was considerable and progress was very slow. In 1964, only 144 of the DPD's 4,390 officers were African American, and most held the lowest rank of patrolman. The liberal Cavanagh administration made the hiring of black officers a public priority but denied that its "color-blind" policies were discriminatory and insisted that African Americans rarely applied and just did not want to be police officers. This claim was disingenuous, partly because it failed to acknowledge that the constant racism that black officers faced from white officers was undoubtedly a factor, but also because it denied the clear racial discrimination in the subjective and allegedly merit-based hiring process and ignored how white community and familial networks supplied many new police recruits (sons and nephews of white officers often joined the force after high school graduation). By 1968, the representation of African American officers in the DPD had increased to 6%, but shifting demographics meant that the racial population of the city of Detroit had increased to around 40%, almost seven times greater than the rate of black policemen on the force (chart at right).

In 1967, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC) started the Police Recruitment Project, a statewide campaign to make an "active and intensive effort to hire more Negro officers in police departments." The MCRC initiative argued that aggressive affirmative action was necessary and that police departments should actively "recruit in the Negro communities and use resources which will reach the Negro community." The main targets were African American men, but the MCRC also urged police departments to hire "Latin American" and women officers as well. The Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police was a partner in this effort, giving it the law enforcement stamp of approval.

This image of an African American police officer assisting white women in Detroit, and the "police want you" advertisement from a 1968 recruitment brochure at the top of this page, typified the MCRC's outreach efforts to African American communities. (Read the full Police Recruitment Project brochure in the gallery below).

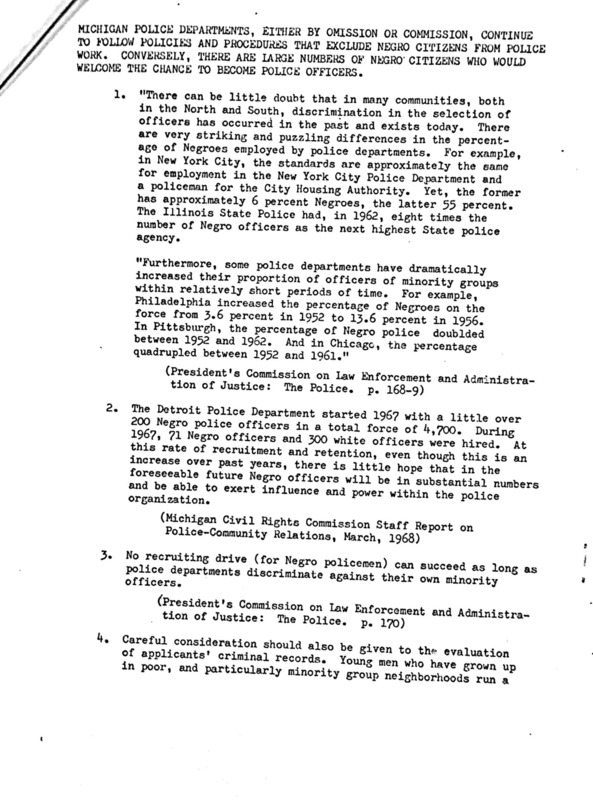

In April 1968, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission released a report on how to "improve police community relations" (reproduced in full on the previous page) that was highly critical of the racially exclusionary policies of the DPD and other urban police departments in Michigan. The MCRC stated that unless current DPD hiring and promotion policies changed dramatically:

The MCRC specifically argued that the written examinations and subjective evaluations in the recruitment and promotion process discriminated against African American officers. And its report pointed out that the exclusion of applications from anyone with even a minor arrest record, on "moral character" grounds, was also racially discriminatory because so many African Americans acquired police records because of who they were and where they lived, rather than actual criminal activity (gallery, second from left).

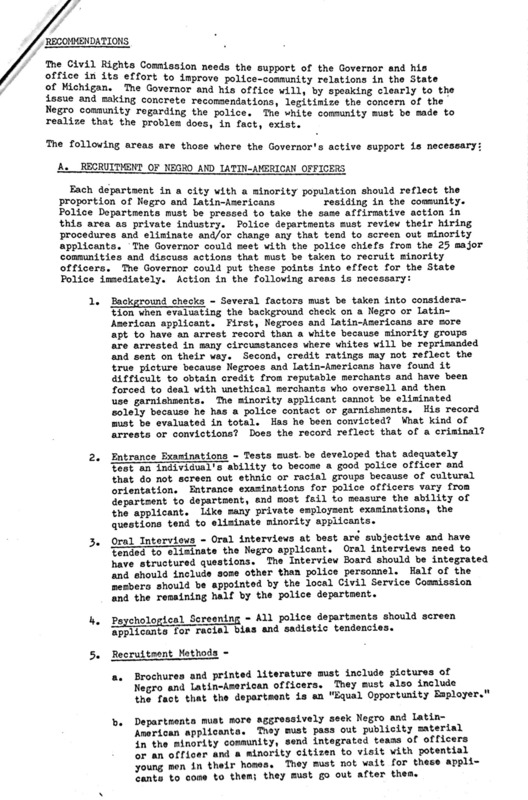

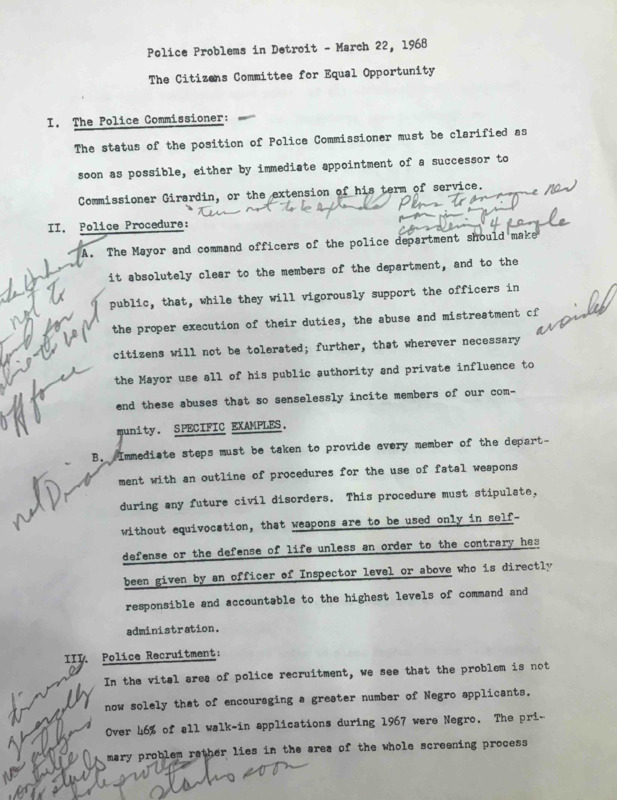

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission's 1968 report recommended aggressive affirmative action initiatives to ensure that the percentage of African American and Latino officers in every police department reflected the percentage of each minority group in the city population at large (gallery below). Note: despite asking for applications from women in its advertising campaign, the MCRC did not make any specific recommendations about hiring women officers in its policy report. The Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity, a liberal Detroit-based civil rights organization that was closely allied with the MCRC, made the same recommendations for affirmative action in a spring 1968 meeting with Mayor Cavanagh about DPD reform (below right).

Diversifying the DPD (Slowly)

In its spring 1968 meeting with Mayor Cavanagh, the Citizens Committee for Equal Opportunity pointed out that African Americans made up almost half of DPD applicants during 1967, but only around one-fifth of the officers ultimately hired (above right). The CCEO blamed racial discrimination in the job evaluation process and argued that a majority of all new police officers should be African American, along with more top commanders and the inspectors in charge of every "ghetto precinct." A broad spectrum of civil rights groups made similar demands, with the goal of reaching a 50-50 ratio on the police force as soon as possible.

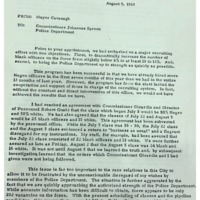

The Cavanagh administration responded by pledging a recruiting drive to quickly double the number of black officers to 12% of the force. The mayor personally instructed the DPD to ensure that each new class of monthly recruits be at least 50% African American. The DPD personnel department complied for one class in the summer of 1968 and then returned to what Cavanagh himself called "business as usual." In August, the incensed mayor accused the DPD of having "subverted" his order and wrote a letter (below left) to his new police commissioner, Johannes Spreen, stating:

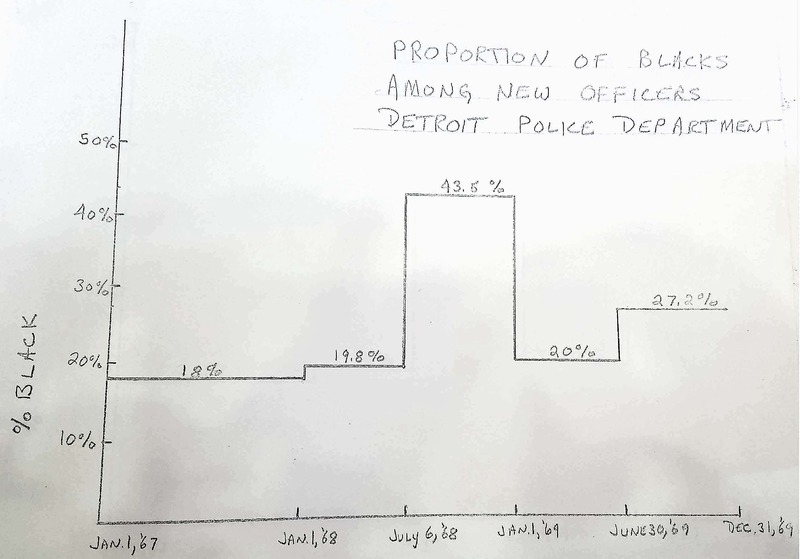

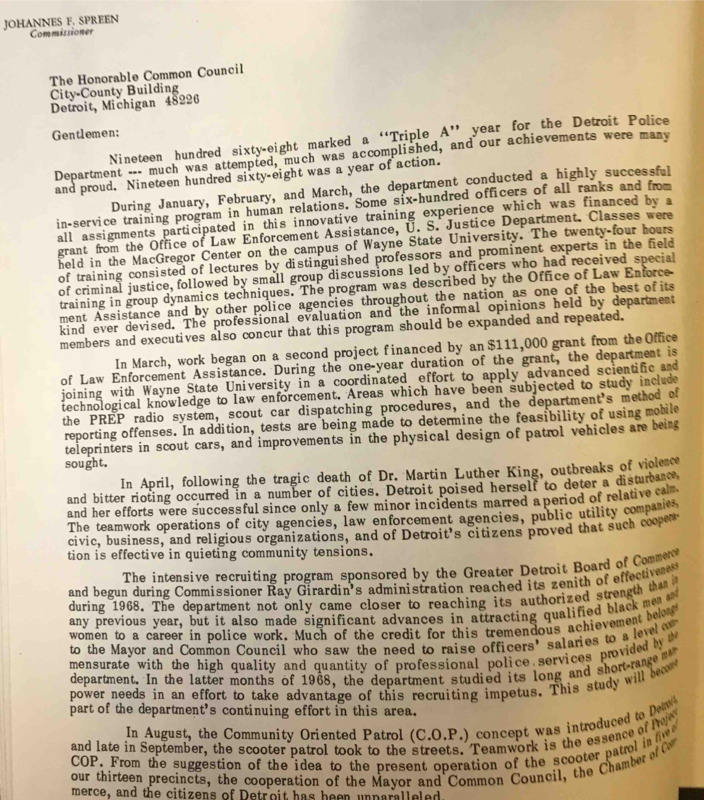

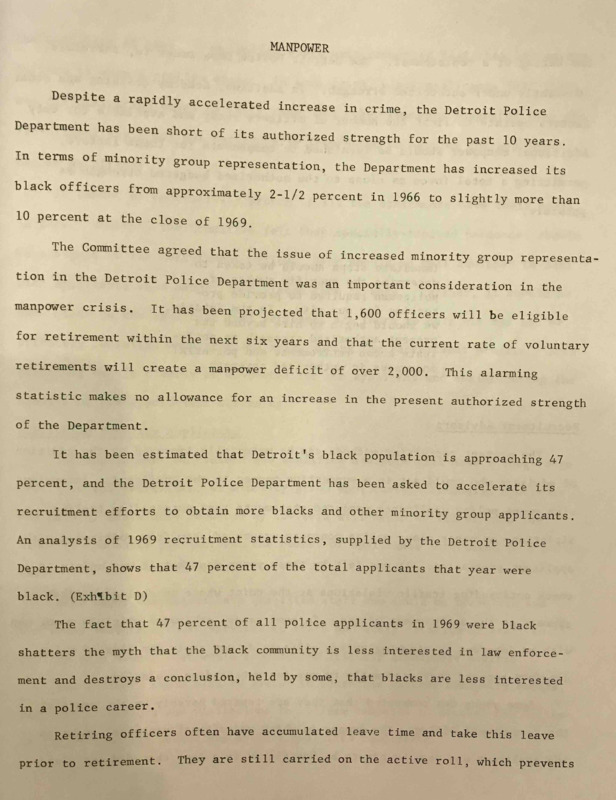

Because the DPD had refused to comply with his mandate, Cavanagh ordered the personnel department to make sure that every new class of officers in training had four African Americans for every one white policeman, until further notice. The DPD did not comply with this direct order either (graph at right). For a brief period in the second half of 1968, while under sustained pressure from the mayor's office as well as civil rights organizations, the percentage of new police officers who were African American exceeded two-fifths of the total. At the end of the year, Commissioner Spreen praised the DPD for its "tremendous achievement . . . in attracting qualified black men and women to a career in police work" (gallery below). And then in 1969, the DPD reverted to a level of recruitment that barely surpassed its efforts in 1967 and remained well below the percentage of African Americans in the city population.

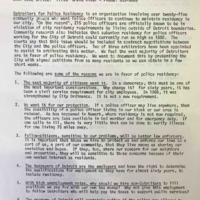

Black community-based organizations proposed strict enforcement of a requirement that police officers lived inside the city limits as one key solution to the underrepresentation of African Americans on the force (right). In 1968, twenty-five civic and political groups formed Detroiters for Police Residency to resist the DPOA police union's attempt to weaken or remove the residency requirement for municipal employees through labor contract neogotiations. The main association for black police officers, the Guardians of Michigan, joined this coalition as residency was one of many issues where they felt unrepresented by the ultraconservative and essentially white DPOA union. Detroiters for Police Residency contended that as many as 1,500 white officers were living in the suburbs, in violation of municipal policy, and that the DPD was deliberately ignoring this fact. The group's manifesto argued that police officers should be "a part of our community" and that upholding the residency requirement would bring fairer and more effective law enforcement and create more jobs for minority groups, including Latinos as well as African Americans.

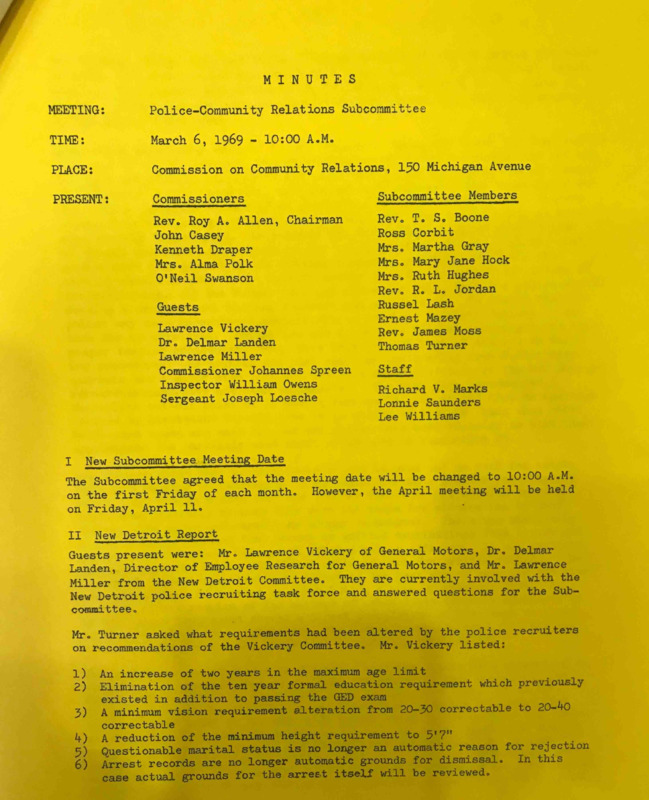

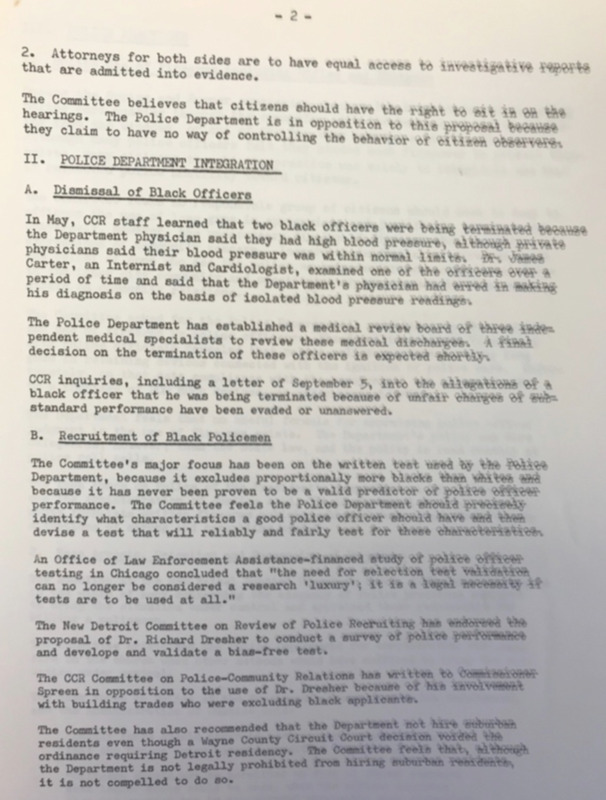

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR) operated as a watchdog on the DPD's recruitment and promotion policies, working closely with the New Detroit Committee, which prioritized affirmative action to reduce African American unemployment more generally in its response to the July 1967 Uprising. The DCCR repeatedly argued that the police department's written exam for applicants, which excluded African Americans at 3 times the rate of whites, was racially discriminatory and "has never been proven to be a valid predictor of police officer performance." Under pressure, the DPD made some modest changes in 1969, such as reducing its height requirement to 5'7'' (almost half of all rejections in 1968 were based on height) and no longer automatically rejecting applicants with "questionable marital status" or arrest records, which would instead be "reviewed" (note that an arrest record is not a conviction). The DPD refused to eliminate its written "intelligence" test, despite its uselessness, and also defended its subjective oral evaluation process that reformers argued reproduced the racial bias of the white officers who ran it. In a tense meeting with the DCCR in spring 1969, Commissioner Spreen denied that the acceptance of white applicants at twice the rate of black applicants revealed any racial discrimination by the DPD (below, second from left).

The DPD force increased from 6% African American in 1966 to 10% by the end of 1969, a historically unprecedented expansion but still well below Mayor Cavanagh's promised target. In a December 1969 evaluation, the DCCR continued to criticize the DPD's insistence on using its racially biased written exam and also accused the DPD of a pattern of terminating black officers for spurious and discriminatory reasons, such as high blood pressure or unfair performance reviews from white superiors. And, after the DPOA union convinced a local judge to void the city's residency requirement, the DCCR urged the police department not to hire suburban residents anyway but instead to prioritize those living in the city of Detroit, in order to advantage African Americans.

The white DPD leadership, including Commissioner John Nichols after his ascension in 1970, repeatedly defended the department against charges of racial discrimination and insisted that all "qualified people" were hired through its merit-based process. Nichols pledged commitment to the efforts to "attract and maintain qualified black officers" but also expressed discomfort with the affirmative action "numbers game." The new commissioner's position reflected a longstanding dynamic within the DPD, based on acknowledging the need for better racial representation without implementing the structural changes needed to transform the force. The main reform proposed in the "manpower" section of the 1970 Police Community Relations Project report, which Nichols played a key role in crafting, was that the personnel in the police recruitment office should be friendlier and more polite to black applicants rather than treating them with hostility. The report (below right) acknowledged the racial disproportionality in the DPD's hiring outcomes but otherwise did not take a clear position on when and how the current procedures would be modified.

Community Policing "Reform" as Public Relations

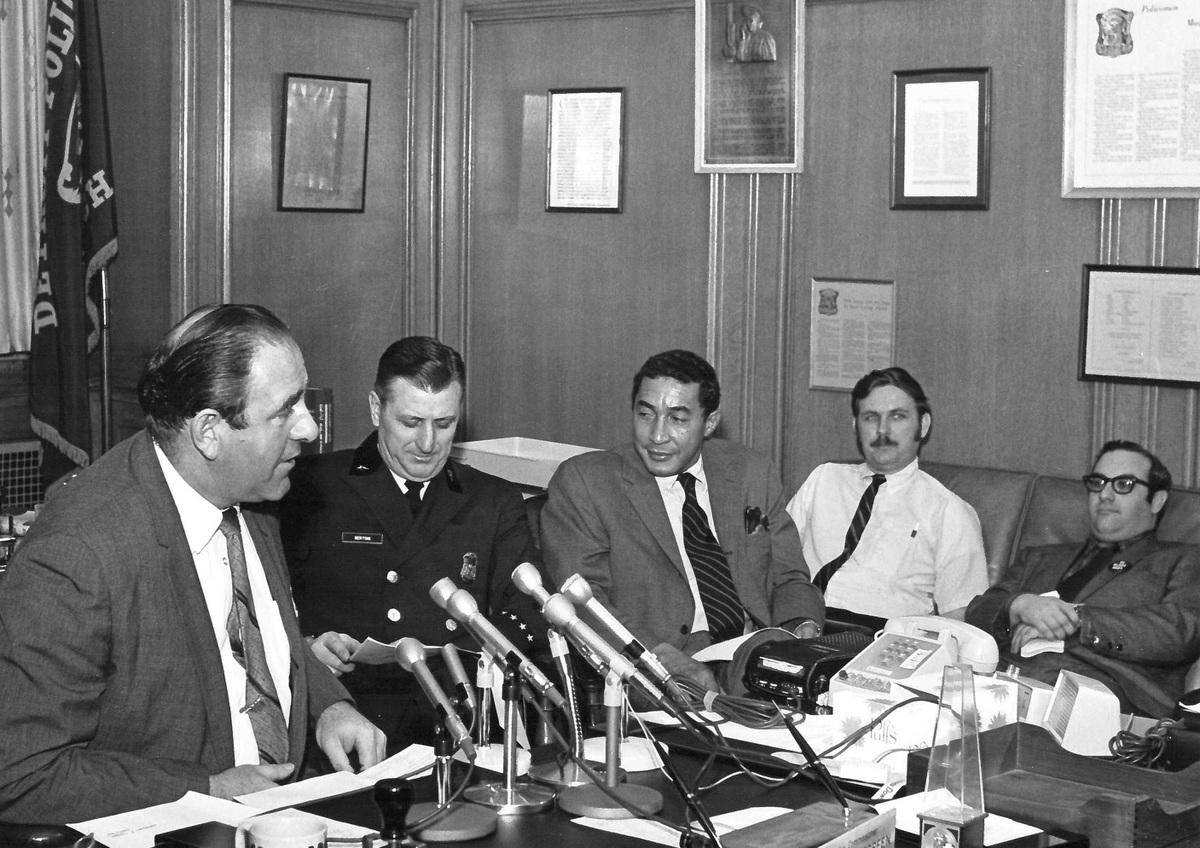

Commissioner Johannes Spreen, who succeeded Ray Girardin in the summer of 1968, presided over the expansion of stop-and-frisk policing, did nothing to reform the DPD's patterns of violence against black residents and its failure to investigate police brutality and misconduct, and denied that the police department was more than 90% white in a near-majority black city because of racial discrimination (above). Instead, Spreen's main innovation as DPD commissioner was to professionalize the department's public relations messaging, modernize its communications with news organizations, and promote its "community policing" strategies through imagery of racial unity and harmony.

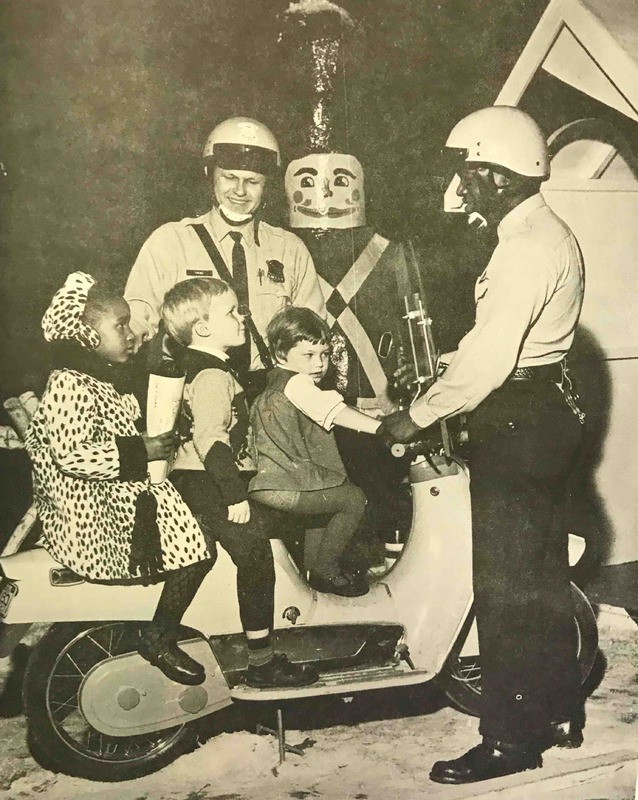

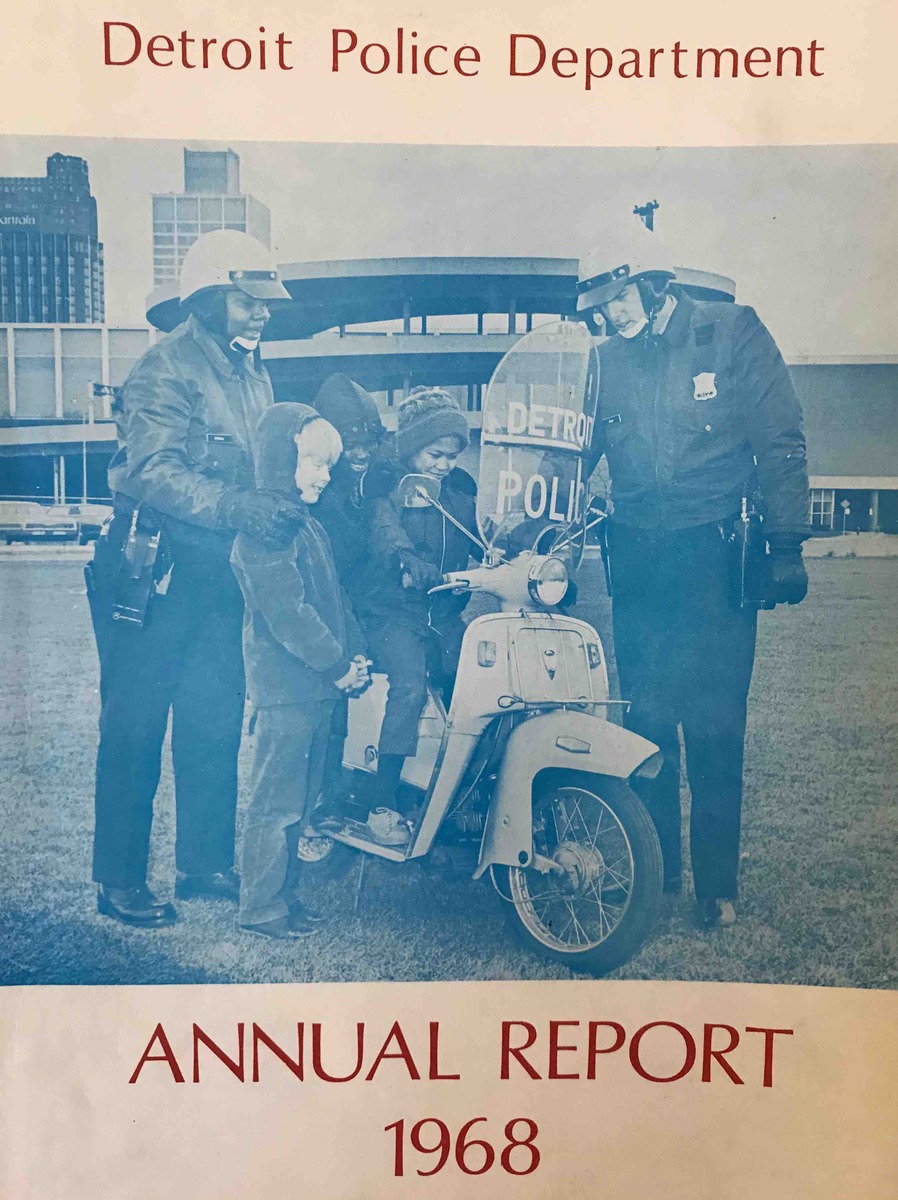

In August 1968, soon after taking charge, Commissioner Spreen introduced the Community Oriented Patrol, a motor scooter unit "to promote the teamwork relationship between the police department and the community." The members of the COP scooter patrol included both police officers and specially trained civilian volunteers, "fostering police-people harmony." In his end-of-year report to the mayor and city council (above left), Spreen identified the scooter program as one of the main accomplishments of the DPD in 1969. The public relations marketing of the COP patrol featured images of African American officers on motor scooters, often posing with Commissioner Johannes Spreen or giving out presents to young children at holiday events (right).

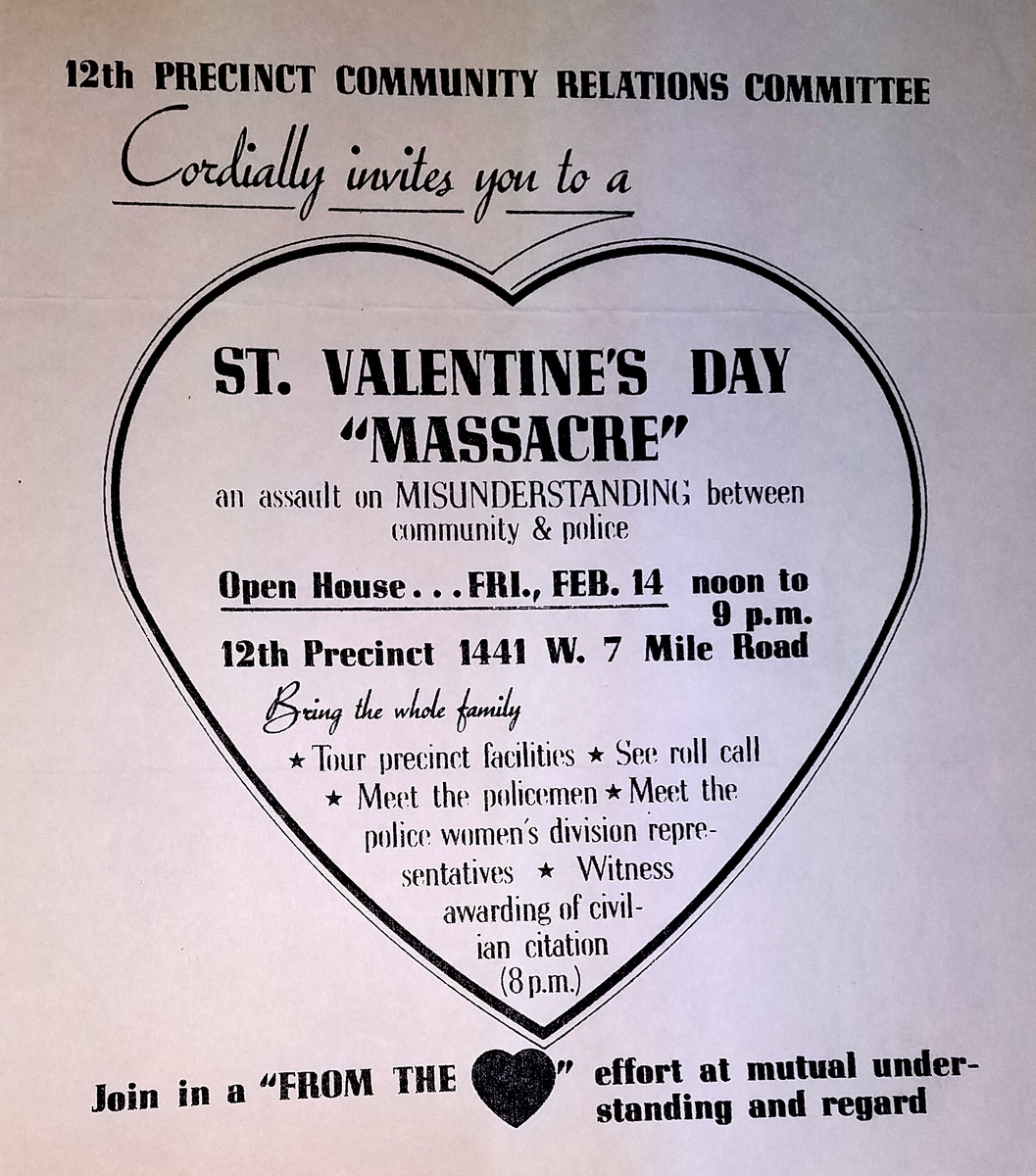

Spreen also promoted better police-community relations through neighborhood-based meetings in police precincts, which he often attended. On February 14, 1969, for example, Spreen personally hosted a St. Valentine's Day "Massacre" at the Palmer Park headquarters in the 12th Precinct, billed as an "assault on MISUNDERSTANDING between community & police" (gallery below). The family-oriented event featured tours of the precinct station's squad rooms and cell blocks, exhibits on police radio communications, and an opportunity to climb inside a police vehicle and learn how the radar gun worked. Pupils from a nearby junior high school created posters and decorations for the event, "showing that students can work hand-in-hand with police and break-down the impersonal relationships."

The DPD under Commissioner Spreen also escalated its community engagement with teenagers through organizations such as YMCA, police-youth sports leagues, and the Boy Scouts. In her book on police reforms during the 1960s and 1970s, historian Elizabeth Hinton argues that these forms of "community policing" actually operated to increase the criminalization of poor black neighborhoods by deeply embedding law enforcement in social welfare organizations, where police officers often cracked down hard on "trouble-making" and "delinquent" (or even so-called "pre-delinquent") youth at the same time that they handed out presents and played sports with the "good kids." This was definitely a legacy of community policing in Detroit, but Spreen's public relations and community policing initiatives also sought to address the more specific problem of the DPD's extremely tense and poor relationship with African American neighborhoods after the 1967 Uprising. The DPD under Spreen attempted to recruit the "law-abiding black community" into an alliance with law enforcement, just as reform commissioners had been trying to do since Mayor Cavanagh appointed George Edwards in 1962, hoping to gain the support of African American neighborhood associations and civic groups for the escalation of the punitive wars on crime and drugs in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The Detroit Urban League partnered with the DPD in the community policing initiative to mobilize citizens to fight crime. The DUL, a middle-class and business-oriented civil rights organization, had long combined its support for reforms such as racial diversification of the police force and "color-blind" law enforcement with demands that the DPD protect law-abiding black citizens from street crime. After the 1967 Uprising, the Detroit Urban League blamed the "race riot" on both police brutality and a "deviant minority within a law-abiding black community," and the organization repeatedly targeted poor and working-class black youth in its demands for crime control. In 1969, the Detroit Urban League launched a "Citizens Campaign for Crime Prevention" (right) that included more than 400 block clubs, neighborhood associations, and church groups. Francis Kornegay, the DUL's longtime leader, declared that "crime in our streets is tragic, frightening, terrible, maddening and is a horror by day, a nightmare by night." The DUL urged African American citizens to work with the Detroit Police Department to fight a "war" against crime and believed that such cooperation would enhance police-community relations, the essence of the community policing reform vision.

The gallery below contains additional images and flyers from the DPD's public relations and community policing campaign under Commissioner Spreen.

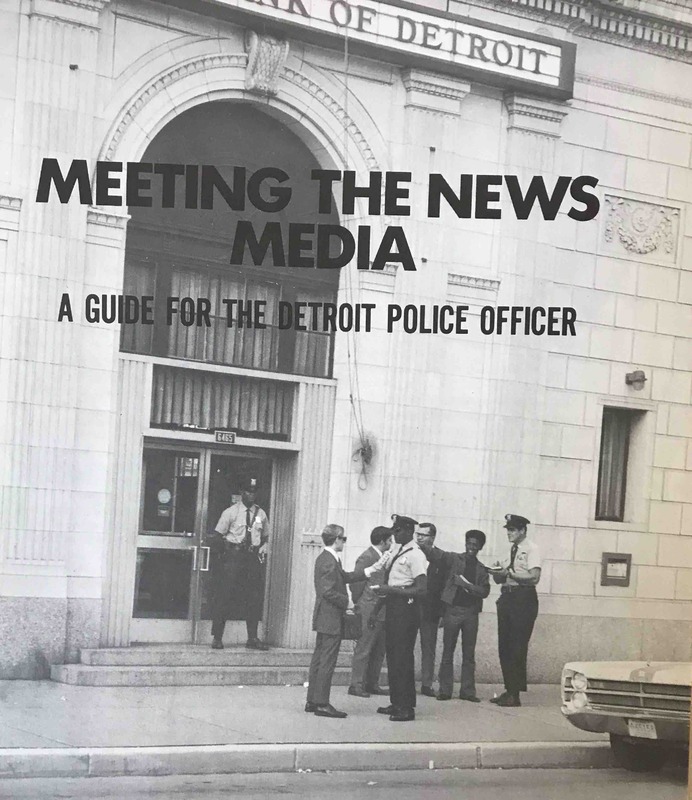

Media Campaign: Community Relations Bureau

The Detroit Police Department continued to prioritize its public relations and news media outreach in the early 1970s, under commissioners Patrick Murphy and John Nichols. The DPD's enhanced public relations bureau began producing short television segments to enable "the public to learn with the police and to see the difficulties and problems inherent in police work." The Police Community Relations Project Report, completed in June 1970, also emphasized the need for the DPD to develop a better community relations program and a more coordinated public relations strategy, in addition to training individual police officers on how to interact with newspaper and television journalists (below left).

Based on this report, Commissioner Murphy created the Community Relations Bureau in 1970 to coordinate the department's police-community relations programs (below, second from left). The Community Relations Bureau interacted with neighborhood block clubs, civic groups, and youth programs to improve police relations in order to enhance crime control. This did not always go smoothly, of course; the gallery below includes a complaint from the Michigan Civil Rights Commission charging the Community Relations Bureau with excluding the representative of a local black militant organization, the East Side Voice of Independent Detroit, from a precinct police-community relations meeting because of his reputation as a critic of police brutality.

The Police Community Relations Project report, as described on the previous page, portrayed police brutality as a problem of miscommunications and erroneous perceptions, "imagined" by many black residents and wrongly charged by "antagonistic" groups. The DPD's preferred solution, therefore, was a public relations campaign to convince the "community" (meaning the black public, because the white majority was already convinced) of its side of the story.

Commissioner Murphy, who had been appointed in January 1970 by new mayor Roman Gribbs, devised the "Meeting the News Media" initiative as the centerpiece of this public relations campaign. The DPD's communications officers even boasted of their intentions and claimed immediate success in a feature in Public Relations Journal, "How Detroit Raised the Blue Curtain," published in January 1971. According to DPD sources, the June 1970 Police Community Relations Project report, and other internal studies, convinced the department's leaders of the depth of public misunderstanding of the operations of officers on the street. The DPD hierarchy also recognized that the general public believed that officers followed the rules of the "Blue Curtain" and refused to implicate one another, even in serious wrongdoing. The "Meeting the News Media" campaign therefore sought to make clear that the DPD would not tolerate officer misconduct while--most urgently--getting the police side of the story out when civilian groups made "unfounded" allegations about police brutality.

The "Meeting the News Media" guidelines included a number of regulations that sought to protect the civil liberties of civilians, including suspects and individuals under arrest, evidence of Commissioner Patrick Murphy's reputation as a liberal reformer. Among other changes to previously common police practices, the 1970 guidelines forbade police officers from releasing a suspect's prior criminal history, parading an arrested person in front of the news cameras, or publicly commenting on the potential guilt of someone in custody. The guidelines also required police officers to inform the media, when asked, of the neutral facts of any allegations of police brutality or misconduct made by a citizen group. At the same time, the guidelines urged officers to speak to the news media, "with patience and courtesy," to get their side of the story out when wrongly accused.

Commissioner Murphy also promised that, in the case of "genuine instances of police misconduct," the DPD would respond with "public disavowal of such misconduct, tighter discipline and, where necessary, court action against the offenders." Because Murphy abruptly returned to the NYPD right after the "Meeting the News Media" campaign began, it is impossible to know the extent to which the DPD might have embraced such reforms under his leadership, although there is ample reason to doubt that much would have changed. It also seems likely that Murphy's promise that the DPD would discipline officers for misconduct, and even refer them for prosecution (something that never happened in cases of alleged police brutality), was just another style-over-substance part of the public relations campaign to change the department's image in the media. At any rate, in summer 1970 Mayor Gribbs replaced Murphy with the conservative hardliner John Nichols, who created the deadly STRESS initiative among other crackdowns on African American neighborhoods, and police-community relations got much, much worse.

Sources:

Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Detroit Office, RG 80-17, Michigan State Archives

Michigan Civil Rights Commission, Records Relating to Detroit Police Department, RG 74-90, Michigan State Archives

Detroit Commission on Community Relations/Human Rights Department Records, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Jerome P. Cavanagh Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

New Detroit, Inc. Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit Police Department Additional Papers (1965-1993), Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime (Harvard, 2016)

Andrew F. Wilson, "How Detroit Raised the Blue Curtain," Public Relations Journal (January 1971)